Abstract

Thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) regulate multiple normal physiological and developmental pathways, whereas mutations in TRs can result in endocrine and neoplastic disease. A particularly high rate of TR mutations has been found in human renal clear cell carcinomas (RCCCs). We report here that the majority of these RCCC TR mutants tested are defective for transcriptional activation and behave as dominant-negative inhibitors of wild-type receptor function. Although several of the dominant-negative RCCC TR mutants are impaired for hormone binding, all fail to release from corepressors appropriately in response to T3, a trait that closely correlates with their defective transcriptional properties. Notably, many of these mutants exhibit additional changes in their specificity for different corepressor splice forms that may further contribute to the disease phenotype. Mapping of the relevant mutations reveals that the C-terminal receptor helix 12 is not simply a hormone-operated switch that either permits or prevents all corepressor binding, but is instead a selective gatekeeper that actively discriminates between different forms of corepressor even in the absence of T3.

Thyroid hormone receptor mutants associated with human renal clear cell carcinoma display dominant-negative properties that correlate with alterations in their corepressor recruitment and specificity.

In normal cells, thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) serve as hormone-modulated transcriptional regulators that control important aspects of proliferation, differentiation, and homeostasis (1,2). TRs are encoded by two genes, α and β, the transcripts of which are alternatively spliced to produce three major isoforms able to respond to hormone: TRα1, TRβ1, and TRβ2. TRs are bipolar in their transcriptional properties and repress or activate target gene expression through their ability to recruit corepressors and coactivators (1,2). These auxiliary proteins, in turn, modify the chromatin template and interact with the general transcriptional machinery to yield the appropriate transcriptional output, down or up. On classic target genes, TRs recruit corepressors and repress in the absence of hormone; addition of T3 causes a conformation change in helix 12 of the hormone-binding domain of the receptor, resulting in release of corepressor, the acquisition of coactivators, and transcriptional activation (3,4,5).

Genetic lesions in TRs can give rise to disease (6,7). Mutations in the TRβ isoform, for example, are the most common cause of resistance to thyroid hormone (RTH) syndrome, a human endocrine disorder manifested as a diminished responsiveness to T3 (8,9). RTH syndrome is primarily caused by receptor mutations that impair corepressor release in response to T3 (10,11). As a result, RTH TR mutants operate as dominant-negative inhibitors of wild-type TR (wt-TR) function. Yet other TR mutants are associated with cancer (6,12). V-Erb A is a mutated, retroviral version of TRα1 that cooperates with other oncogenes to produce erythroleukemias, sarcomas, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (13,14,15,16,17). Mutations in both TRα1 and TRβ1 occur at high frequency in spontaneous human HCCs, renal clear cell carcinomas (RCCCs), papillary thyroid neoplasia, and gastric cancers (18,19,20,21,22,23).

RTH syndrome is not associated with an elevated incidence or progression of cancer. Why then do certain TR mutants cause endocrine disorders, whereas others are associated with neoplasia? Unlike the lesions in RTH, which map primarily to the ligand-binding domain, mutations associated with HCC and RCCC span both the DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains of the receptor. The vast majority of TR mutants from HCC possess a dominant-negative phenotype; several also display detectably altered DNA-binding characteristics (24). Related molecular flaws are also exhibited by the v-Erb A mutant (14,25). We have proposed that simple dominant-negative TR mutants, such as those in RTH syndrome, cause endocrine disruption, whereas the v-Erb A and HCC TR mutants may gain oncogenic function, at least in part, by acquiring an additional ability to recognize a distinct set of target genes compared with the wild-type receptors (24). Nonetheless, the factors that determine whether a given TR mutant causes endocrine disruption vs. neoplastic disease remain murky.

To more broadly understand the actions of TR in human neoplasia, we turned to a study of the TR mutations associated with RCCC. We report here that these mutants generally conform to the model that TRs cause disease by functioning as dominant-negatives. In the case of RCCC, these dominant-negative properties correlated with an impaired corepressor release in response to T3 and, unexpectedly, an altered preference for different splice versions of corepressor. These changes in corepressor selectivity were also found for v-Erb A and a subset of RTH TR mutants and mapped to regions in the receptor known to influence the position of helix 12. We propose that helix 12 is a selective gatekeeper that permits access of only specific members of the corepressor family to their docking surface on the wt-TRs in the absence of T3 but that obstructs access of most or all corepressor family members in the presence of T3. Receptor mutations that alter the position of helix 12 can therefore alter corepressor specificity, T3-mediated release, or both. These receptor mutations may enhance target gene repression in cells in which certain corepressor variants predominate or uncouple the mutant receptor from kinase regulatory pathways that inhibit other corepressor variants.

Results

RCCC mutants are defective in T3-dependent transactivation activity and behave as dominant-negative inhibitors of wild-type receptor activity

To characterize the transcriptional properties of TR mutants associated with RCCC (Fig. 1A), we introduced the individual TR alleles into CV-1 cells together with a tk-luciferase reporter containing a consensus T3 response element (TRE). T3 was added or not, and the cells were assayed for luciferase activity 48 h after transfection (Fig. 2). CV-1 cells lack endogenous TR activity, and little or no T3 regulation of the luciferase reporter was observed in the absence of an ectopic TR (data not shown). As expected, introduction of wt-TRα1 into the CV-1 cells repressed luciferase expression in the absence of T3 and increased it in the presence of T3 (Fig. 2A, solid line). Both RCCC TRα1 mutants examined (rc2-TRα1 and rc6-TRα1) repressed in the absence of T3, but neither mutant was able to achieve wild-type levels of reporter activation at any hormone level tested (Fig. 2A, dashed lines). The rc6-TRα1 allele also required more T3 to achieve a given level of gene activation than did wt-TRα1 or the rc2-TRα1 mutant: the EC50 for rc6-TRα1 was about 60 nm, compared with 1–2 nm for wt-TRα1 or rc2-TRα1. Both of the RCCC TRα1 mutants were also strong dominant-negative inhibitors when co-introduced with wt-TRα1 over a wide range of T3 concentrations (Fig. 2B).

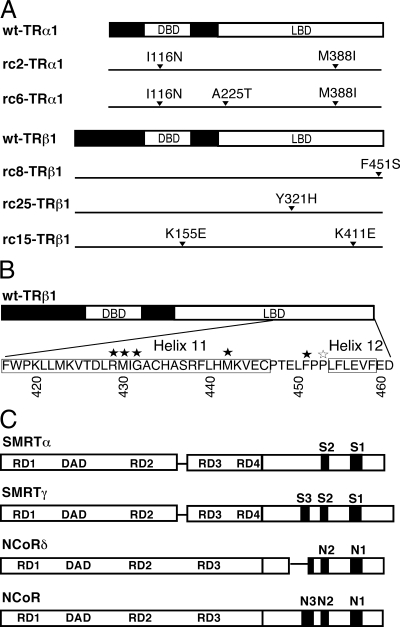

Figure 1.

A, Schematic of TRs associated with RCCC. The DNA-binding domain (DBD) and ligand-binding domain (LBD) are represented in white. The amino acid substitutions are indicated within each mutant sequence. B, Amino acid sequence of helix 11 and 12 of the TR LBD is shown. Substitutions leading to altered corepressor specificity are indicated by black stars and those that do not by white stars. C, Schematic of SMRT and NCoR corepressor isoforms. Repression domains (RD1–RD4) and the deacetylase activating domain (DAD) are indicated. CoRNR boxes (S1–S3 in SMRT isoforms, and N1–N3 in NCoR isoforms) are represented as black boxes.

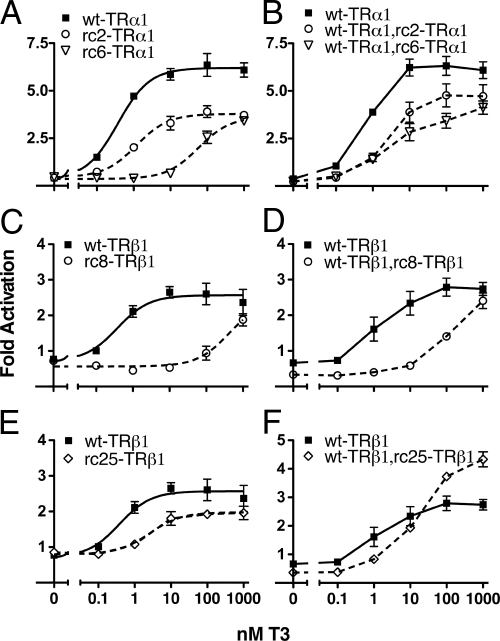

Figure 2.

TR mutants associated with RCCC are impaired transcriptional activators and are dominant-negative inhibitors of wild-type receptor function. A, C, and E, CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with an empty pSG5 vector or a pSG5 vector expressing wild-type (solid lines) or mutant (dashed lines) TRs, along with a DR4-TK luciferase reporter and pCH110-lacZ. After 24 h, cells were treated with the T3 concentrations indicated, harvested 24 h later, and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. Luciferase activity is shown relative to β-galactosidase activity. Fold activation refers to the fold change of luciferase activity compared with the empty pSG5 control. Average and sem values are shown from at least three independent experiments. B, D, and F, CV-1 cells were transiently transfected as above, except wild-type and mutant receptor were added together at a 1:5 ratio (dashed lines). Solid lines represent the wild-type receptor transfected with five times the amount of empty pSG5 vector.

The TRβ1 alleles displayed both commonalities and differences compared with the TRα1 alleles. Wild-type TRβ1 repressed reporter expression in the absence of T3 and induced in response to T3, displaying an EC50 very similar to that of wt-TRα1 but a lower maximal activity (2.5- vs. 6.5-fold; Fig. 2C). Both of the RCCC TRβ1 mutants (rc8-TRβ1 and rc25-TRβ1) repressed reporter expression in the absence of T3 but required higher than normal levels of T3 to activate (Fig. 2, C and E). When coexpressed with wild-type receptor, the TRβ1 mutants were dominant-negatives at low hormone conditions yet lost this dominant-negative behavior at the higher T3 concentrations (≥10 nm for rc25-TRβ1, ≥1000 nm for rc8-TRβ1; Fig. 2, D and F). We conclude that RCCC TR mutants are defective in their ability to respond to T3 (i.e. their EC50), in their maximum ability to activate transcription independent of T3 concentration, or in both properties. We next explored the molecular basis for these defects.

Changes in DNA, hormone, and coactivator binding properties contribute to, but do not fully explain, the dominant-negative properties of the RCCC TR mutants

Both rc2-TRα1 and rc6-TRα1 contain mutations in their DNA-binding domains that have been reported to impact their recognition of certain DNA elements (21). Using an EMSA, we determined that wt-TRα1 bound strongly to the TRE found in our luciferase reporter in vitro, both as homodimers and as heterodimers with retinoid X receptor-α (RXRα) (Fig. 3). The rc2-TRα1 and rc6-TRα1 mutants were slightly impaired in TRE binding as homodimers but displayed fully wild-type binding as heterodimers with RXRα (Fig. 3). We conclude that the defective reporter activation properties of the RCCC TR mutants were not primarily due to an inability to recognize the TRE used here.

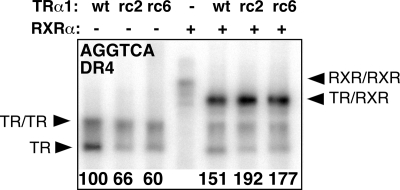

Figure 3.

RCCC TRα1 mutants bind DNA. Wild-type and mutant TRs were incubated with a DR4 radiolabeled probe, alone or with RXRα; the resulting protein/DNA complexes were resolved by gel electrophoresis and visualized by phosphorimager analysis. TR monomers (TR), homodimers (TR/TR), RXR homodimers (RXR/RXR) and heterodimers (RXR/TR) are indicated by arrowheads and quantified below the panel relative to the wt-TRα1 homodimer, defined as 100. Data shown here are representative of multiple experiments.

The changes in EC50 in our luciferase assays suggested that several of the RCCC mutants might be defective in hormone binding. Hormone binding confers a conformational compaction on the nuclear receptors that increases their protease resistance; relative hormone affinities can be determined by assaying protease resistance over a range of T3 concentrations (26). By this method, both the wt-TRα1 and wt-TRβ1 receptors exhibited half-maximal protection at 1–2 nm T3 (Fig. 4, A and B, solid lines, and supplemental Fig. S1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org), consistent with published dissociation constants and with their EC50 values in Fig. 2. Three of the RCCC mutants required more T3 than did wild type to be protected from protease degradation: rc6-TRα1, rc8-TRβ1, and rc25-TRβ1 (Figs. 4, A, C, and E, dashed lines, and supplemental Fig. S1). In contrast, the rc2-TRα1 mutant was indistinguishable from wt-TRα1 in this assay (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. S1).

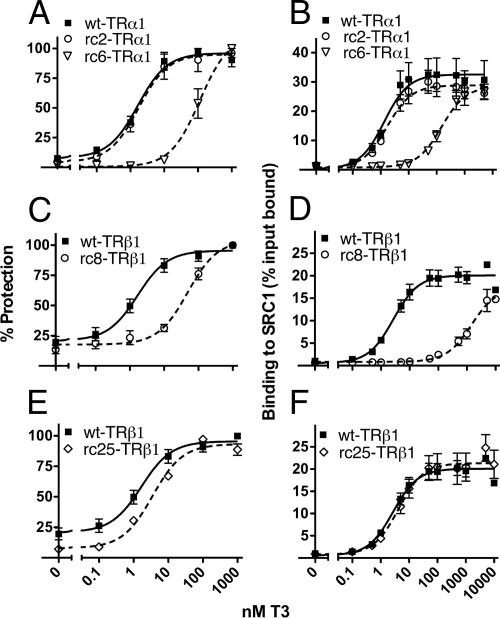

Figure 4.

Certain, but not all, RCCC TR mutants are impaired for T3 binding and require higher hormone concentrations than wild-type to interact with coactivator. A, C, and E, Radiolabeled TRs were incubated with 0.05 U elastase and increasing concentrations of T3 in a protease protection assay. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the percent recovery of the receptor protease-resistant core (maximum = 100%) is indicated for each T3 concentration in A, C, and E. For each receptor, the products of proteolysis were quantified in each lane and divided by the input. Representative autoradiographs of SDS-PAGE gels are shown in supplemental Fig. S1. B, D, and F, Radiolabeled TRs were incubated with a GST-SRC1 construct at the T3 concentrations indicated. The percentage of input TR bound at each T3 concentration is shown. The corresponding wild-type data (solid lines) are superimposed in all panels for ease of comparison. The average and sem values from three or more independent experiments are shown for all experiments.

Notably, the defects in hormone binding by these mutants contributed to but did not fully account for their defects in reporter gene regulation. The rc2-TRα1 mutant possessed a wild-type affinity for T3 yet was impaired for transcriptional activation and behaved as a dominant-negative over the entire range of T3 concentrations tested (compare Figs. 2, A and B, and 4A). The rc6-TRα1 exhibited a combination of two defects: a reduced affinity for T3 that displaced both its EC50 and its protease protection to the right in Figs. 2 and 4 and an additional defect that prevented full transcriptional activation even at the highest T3 concentrations tested (levels sufficient to maximally protect this mutant from protease in vitro; Fig. 4). Similarly, the rc8-TRβ1 and rc25-TRβ1 mutants also had reduced affinities for T3 that displaced both their EC50 and protease protection to the right in Figs. 2 and 4. Although very high levels of T3 reversed the dominant-negative activities of these two TRβ1 mutants, the rc25-TRβ1 mutant never reached a fully wild-type activity on the reporter when tested alone, and considerably more T3 was required for the rc8-TRβ1 mutant to activate reporter gene expression in vivo compared with the T3 levels required for protease protection in vitro (the EC50 value for this mutant was about 8-fold higher than its affinity for T3; Figs. 2 and 4).

We next assayed these mutants for the ability to recruit SRC1, an important coactivator for wt-TRs. Neither wild-type nor mutant receptors bound significantly to a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC1) construct in the absence of T3 (Fig. 4, B, D, and F) or to a GST-only negative control (data not shown). T3 induced SRC1 binding by all receptors tested (Fig. 4, B, D, and F). The rc8-TRβ1 mutant required higher than normal T3 to bind coactivator and did not quite reach wild-type levels at the highest T3 concentration tested. In contrast, however, the rc2-TRα1, rc6-TRα1, and rc25-TRβ1 mutants displayed fully wild-type SRC1 binding when sufficient T3 was added to compensate for any defect in their hormone affinity (compare Fig. 4, left and right panels). We conclude that neither their hormone binding nor coactivator binding properties alone can fully account for the transcriptional defects observed for many of the RCCC mutants in Fig. 2.

The RCCC mutants exhibit additional alterations in their interactions with corepressors that more completely account for their transcriptional defects

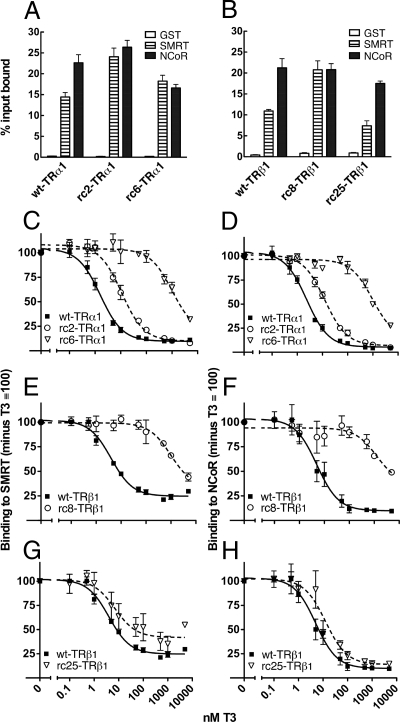

The silencing mediator of retinoic acid and TR (SMRT) and nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) family of corepressors helps repress transcription in the absence of T3 and helps constrain activation in the presence of T3. SMRT and NCoR share 50% amino acid identity and display closely related biochemical properties; despite these similarities, SMRT and NCoR are differentially expressed in different tissues and display distinct preferences for different nuclear receptor partners (27). We first examined the ability of the wild-type and RCCC mutant TRs to bind to these corepressors in the absence of T3. As previously published, both wt-TRα1 and wt-TRβ1 displayed a preferential interaction with NCoR compared with SMRTα under these conditions (Fig. 5, A and B) (28,29,30). Unexpectedly, the rc2-TRα1, rc6-TRα1, and rc8-TRβ1 mutants eliminated this preference, binding to both NCoR and SMRTα nearly equally (Fig. 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

RCCC TR mutants display altered corepressor specificity and an impaired release from SMRTα and NCoR. A and B, Radiolabeled TRs were incubated with a GST (white bars), GST-SMRTα (striped bars), or GST-NCoR (black bars) construct in the absence of T3, and the percentage of input TR bound to each GST fusion was determined. C–H, Radiolabeled TRs were incubated with a GST-SMRTα or GST-NCoR construct at the T3 concentrations indicated, and the percentage of input TR bound to each GST fusion was determined. Values shown are relative to the binding seen for each TR in the absence of T3 (defined as 100) for ease of comparison of the different EC50 values. The wild-type data (solid lines) are superimposed to facilitate comparisons. Average and sem values are shown from more than three independent experiments.

We next examined corepressor release by T3. Both wt-TRα1 and wt-TRβ1 released SMRTα and NCoR at concentrations of hormone (1–4 nm) comparable with those required to confer protease protection and coactivator binding (compare Fig. 5, C and F, with Figs. 2 and 4). In contrast, all four RCCC TR mutants required abnormally high levels of T3 to release corepressor (Fig. 5, C–H; corepressor binding in the absence of T3 was defined as 100% for each receptor to facilitate comparison). Notably, the effects of the mutations on corepressor release were generally more severe than their effects on T3 or coactivator binding. Approximately 50% of NCoR and SMRTα remained bound to the rc6-TRα1 mutant at 1000 nm T3, a concentration sufficient to fully recruit SRC1 coactivator. Similarly, the rc2-TRα1 mutant, unimpaired in T3 and in coactivator binding, nonetheless required approximately 10-fold more hormone to release corepressor than did wt-TRα1. The rc25-TRβ1 mutant required approximately 2-fold more T3 to release corepressor than to bind coactivator. These results suggest that an impaired T3 release of corepressors, possibly linked to a change in corepressor recognition specificity, contributes to the transcriptional defects observed with these RCCC mutants.

Multiple distinct genetic lesions operate together to produce the combined transcriptional defects observed for many of the RCCC mutants

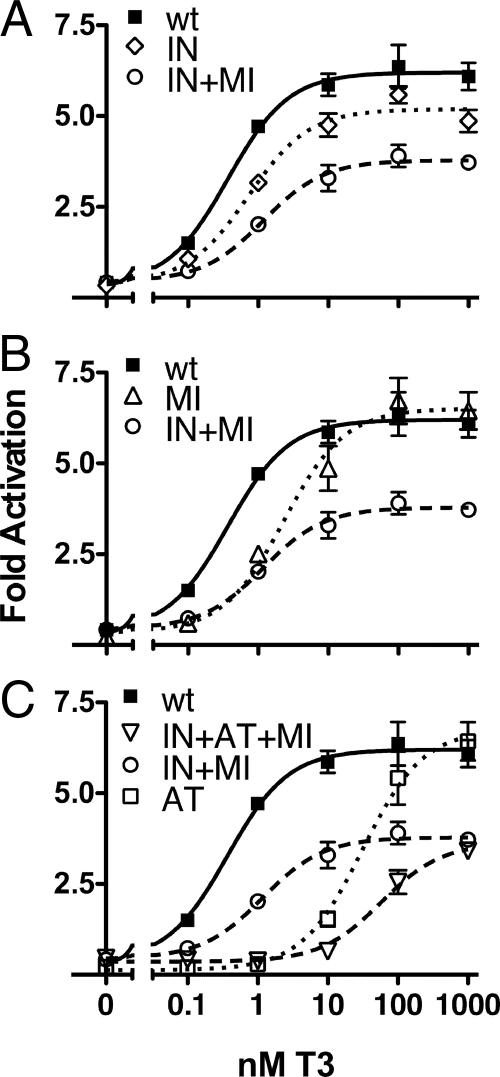

Many RCCC TR mutants contain more than one genetic lesion each; for example, the rc2-TRα1 mutant contains two mutations, and the rc6-TRα1 mutant contains these two plus a third (Fig. 1A). To dissect their unique contributions, we introduced these genetic lesions individually into separate TRα1 constructs and repeated our assay panel. In the absence of T3, all single mutants repressed luciferase activity indistinguishably (Fig. 6). However, in the presence of hormone, we observed distinct activation profiles for each of the individual mutants. In response to T3, the I116N-TRα1 single mutant (denoted IN) activated reporter expression more strongly than did the rc2-TRα1 double mutant bearing both the I116N and the M388I substitutions (IN+MI) but did not achieve wild-type levels even at the highest T3 levels tested (Fig. 6A). Reciprocally, the M388I lesion (MI), tested alone, permitted fully wild-type levels of activation but required higher than wild-type levels of T3 to do so (Fig. 6B). The two mutations that compose rc2-TRα1 mutant therefore function together to impair both the EC50 value and the absolute level of transcriptional activation.

Figure 6.

Individual TRα1 mutations combine to yield the overall transcriptional defects characteristic of each RCCC mutant. A–C, Transient transfections of CV-1 cells were performed and analyzed as described in Fig. 2, using TRα1s representing the individual mutations that compose the rc2- and rc6-TRα1 mutants (dashed lines). Mutations are identified in an abbreviated form omitting the codon number (e.g. M3881 is MI). The rc2-TRα1 mutant is therefore IN+MI and the rc6-TRα1 mutant is IN+AT+MI. The wt-TRα1 data (solid lines) are superimposed for ease of comparison.

The rc6-TRα1 mutant includes the mutations found in rc2-TRα1, together with an additional substitution in its ligand-binding pocket (A225T). A TRα1 bearing this single mutation (AT) was severely impaired in its ability to activate in response to T3 (EC50 >30 nm T3; Fig. 6C). Combining the A225T mutation with the I116N, M338I mutations in rc2-TRα1 added this additional hormone-response defect to an already impaired receptor, resulting in the phenotype displayed by the triple-substitution rc6-TRα1 mutant (Fig. 6C, compare IN+AT+MI with IN+MI). Our results indicate that the genetic lesions found in these RCCC TR mutants combine to produce a merged phenotype that is the sum, or greater, of the individual defects.

The helix 11-helix 12 region of the hormone-binding domain in TR defines corepressor preference

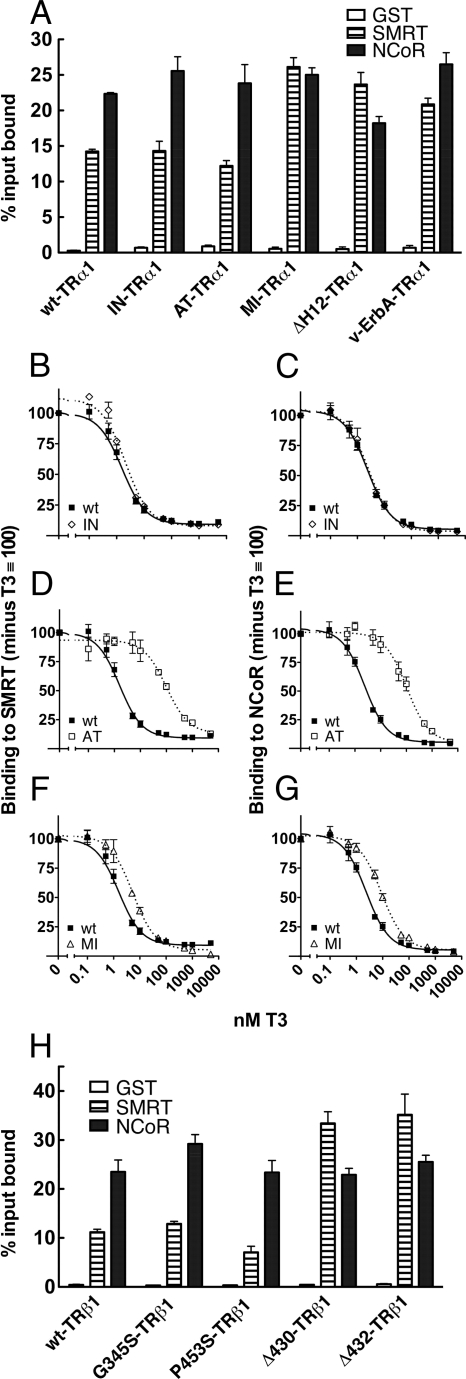

It is known that corepressor/nuclear receptor interaction (CoRNR) motifs in the corepressors interact with a groove composed of helix 3, 4, and 5 on the surface of the nuclear receptors (27). Differences in the CoRNR motifs help define which corepressor interacts with which nuclear receptor. Less is known about the reciprocal sequences in the nuclear receptors that define their preference for one or the other corepressor. To determine which genetic lesion was responsible for the gain in SMRTα binding observed for the rc2-TRα1 and rc6-TRα1 mutants, we first analyzed the effects of the individual mutations in the absence of T3. Of the individual mutants tested, only the M388I TRα1 mutant bound to SMRT and NCoR at equal levels (Fig. 7A), indicating that this mutation alone was sufficient to change the corepressor binding preference to the altered pattern characteristic of the rc2-TRα1 and rc6-TRα1 mutants.

Figure 7.

Mutations in helix 11 and 12 of the receptor ligand-binding domain are responsible for enhanced TR binding of SMRTα. A, TRα1 mutants possessing single mutations, v-ErbA-TRα1, and a TRα1 construct lacking helix 12 were assayed for corepressor binding in the absence of T3 as in Fig. 5; B–G, TRα1 mutants possessing single mutations were analyzed for their ability to release from corepressor in response to T3 as in Fig. 5; H, TRβ1 mutants possessing single mutations were assayed for corepressor binding in the absence of T3 as in Fig. 5.

We next examined the ability of T3 to release NCoR and SMRTα from these single TR mutants (Fig. 7). The I116N-TRα1 mutant released both SMRTα and NCoR at T3 levels indistinguishable from those required by the wild-type receptor (2–3 nm). The M388I mutant required approximately 3-fold as much T3 (5–9 nm) to release either NCoR or SMRTα than did wt-TRα1, whereas the A225T-TRα1 mutant, which is severely impaired for T3 binding, required a comparably higher level of T3 to release these corepressors (∼100 nm). We conclude that the M388I mutation accounts for the moderately increased amount of T3 required to release SMRTα or NCoR from the rc2-TRα1 mutant and that the addition of the A225T mutation accounts for the further increase in T3 required to release SMRTα or NCoR from the rc6-TRα mutant.

The M388I mutation maps to helix 11 of the TRα1 receptor (Fig. 1B) and can alter both the specificity (NCoR vs. SMRTα) and the T3-mediated release of corepressor by this receptor. We wished to determine whether other lesions in this same receptor region resulted in a similar phenomenon. Two mutations mapping to helix 11 in TRβ1, Δ430 and Δ432, were originally identified in RTH syndrome (31). These mutations, each representing a deletion of one amino acid (Fig. 1B), are known to enhance the affinity of TRβ1 for corepressors but were not examined for possible effects on corepressor specificity (32). When tested in our GST pull-down assay, both the Δ430 and Δ432 TRβ1 mutants gained the ability to bind SMRTα to levels greater than NCoR (Fig. 7H). Not all TR mutations associated with RTH syndrome have this effect; neither a G345S mutation between helix 7 and 8 nor a P453S mutation at the very beginning of helix 12 altered the corepressor binding preference (Figs. 1B and 7H).

Mutations within helix 11 can reposition helix 12, a key gatekeeper that controls corepressor binding and release by the wild-type receptors (27). V-Erb A-TRα1 has undergone a deletion of helix 12 (as well as additional point mutations), and in common with our RCCC TRα1 mutants, v-Erb A-TRα1 binds both SMRT and NCoR at close to equal levels (Fig. 7A). The same was true of an artificial TRα1 construct with only the helix 12 deletion (ΔΗ12-TRα1) (Fig. 7A). Therefore, either the loss of helix 12 or its repositioning by certain mutations in the nearby helix 11 or hinge domain curtails corepressor selectivity, probably by permitting a more open access to the corepressor docking surface on the receptor.

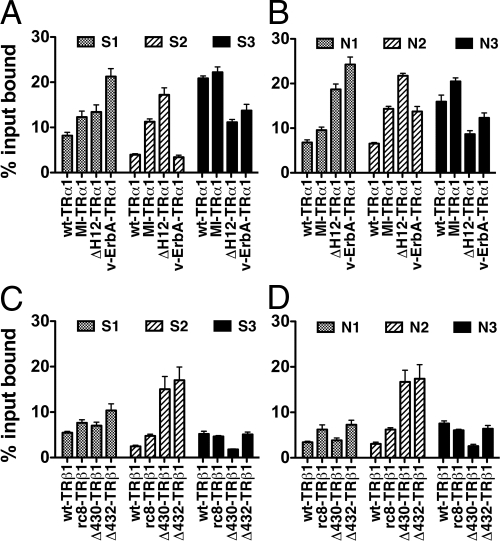

Enhanced SMRTα recognition reflects a gain in the affinity of the receptor for specific corepressor CoRNR boxes

There are two CoRNR motifs present in the SMRTα splice form (denoted S1 and S2) and three CoRNR motifs present in the NCoR splice form (denoted N1, N2, and N3; Fig. 1C) (30). We next tested the mutant and wt-TRs for the ability to bind to these CoRNR boxes individually; we included a third CoRNR box, denoted S3, that, although absent in SMRTα, is present in certain other splice variants of SMRT (Fig. 1C). All assays were first performed in the absence of T3. Consistent with previous studies, both wt-TRα1 and wt-TRβ1 displayed a strong preference for the N3 and S3 motifs and recognized the S1, S2, N1, or N2 motifs much more weakly (Fig. 8) (28,33,34,35). Notably, all six TR mutants that displayed an enhanced ability to bind to SMRTα displayed enhanced binding to the S1 or S2 motifs, whereas binding to S3 was relatively unaffected or inhibited. The specifics differed somewhat for each mutation and for each TR isoform; v-Erb A-TRα1, for example, displayed increased binding to S1 but not to S2, the M388I-TRα1 mutation exhibited elevated binding to both S1 and S2, and the Δ430-TRβ1 and Δ432-TRβ1 mutants manifested a disproportionately increased binding to S2 compared with S1. Intriguingly, the ability of the same mutants to bind to the N1 and N2 motifs was also increased, with binding to N3 unaffected or inhibited. T3 induced release of wt-TRα1 and (at higher T3 concentrations) rc6-TRα1 from all six CoRNR boxes tested (supplemental Fig. S2).

Figure 8.

TR mutants exhibit an enhanced ability to bind to specific SMRT and NCoR CoRNR boxes. A and B, The ability of wild-type or mutant versions of TRα1 to bind to GST fusions representing the individual SMRT and NCoR CoRNR boxes was determined in the absence of T3, as in Fig. 5; C and D, the ability of wild-type or mutant versions of TRβ1 to bind to GST fusions representing the individual SMRT and NCoR CoRNR boxes was determined in the absence of T3, as in Fig. 5.

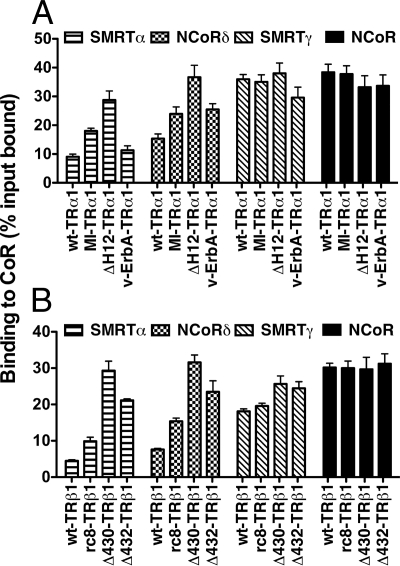

These observations suggested that the increased ability of these mutants to recognize SMRTα originates from their enhanced ability to interact with the two CoRNR motifs, S1 and S2, found in this corepressor, vs. the dependence of the wt-TRs for the third CoRNR motif, N3, present in NCoR but absent from SMRTα. We therefore next tested the ability of the different TRs to recognize SMRTγ, which resembles NCoR by possessing three CoRNR boxes (S1, S2, and S3), vs. NCoRδ, an NCoR splice variant that resembles SMRTα by possessing only two CoRNR boxes (N1 and N2) (Fig. 1C). Corepressors that possessed the third CoRNR box (SMRTγ and NCoR) bound equally strongly to all mutant and wild-type receptors, whereas corepressors lacking the third CoRNR box (SMRTα and NCoRδ) were bound significantly more avidly by the helix 11 and 12 mutants than by the corresponding wt-TRs (Fig. 9). These results suggest that by gaining the ability to recognize S1/N1 and S2/N2, the TR mutants gain the ability to recognize splice forms of both SMRT and NCoR that are only weakly recognized by the wt-TRs.

Figure 9.

The ability of TR mutants to recognize SMRT or NCoR depends on alternative splicing of these corepressors. A, The ability of wild-type or mutant versions of TRα1 to bind to GST fusions representing different splice variants of SMRT and NCoR was determined in the absence of T3, as in Fig. 5; B, the ability of wild-type or mutant versions of TRβ1 to bind to GST fusions representing different splices variants of SMRT and NCoR was determined in the absence of T3, as in Fig. 5.

One of the mutants examined, rc15-TRβ1, may represent either a bystander mutation or play an as yet undefined role in RCCC

One RCCC mutant we analyzed appeared to be an exception from the dominant-negative model. The rc15-TRβ1 mutant bears two lesions, one in the DNA-binding domain and one in the hormone-binding domain (Fig. 1). This mutant was severely impaired in reporter gene activation at all T3 concentrations tested but displayed only very weak dominant-negative properties when co-introduced with wild-type receptor (data not shown). The rc15-TRβ1 mutant exhibited wild-type (or better) binding to T3, wild-type binding to SRC1 coactivator, and wild-type binding and release from SMRTα and NCoR in vitro but was severely compromised in its ability to bind to a consensus TRE (data not shown). This severe defect in DNA binding likely accounts for the lack of dominant-negative function of this mutant on the luciferase reporter. The rc15-TRβ1 mutant may represent a mutation that plays no role in the cancer phenotype, may function on a TRE yet to be elucidated, or may contribute to neoplasia in a manner not yet determined.

Discussion

Mutant TRs associated with RCCC are impaired for transcriptional activation and disrupt wild-type receptor function

Mutations in TRs give rise to a variety of endocrine and neoplastic diseases (6,7). For example, inherited mutations in TRβ1 are a known cause of human RTH syndrome (9), whereas the v-Erb A mutant of TRα1 contributes to leukemogenesis by avian erythroblastosis virus (14,15). The high incidence of spontaneous mutations of TRα and TRβ in human HCC and RCCC is therefore particularly intriguing. The RTH TRβ, v-Erb A, and majority of the HCC TR mutants characterized are impaired for transcriptional activation and can function as dominant-negative inhibitors of the wild-type receptors (11,14,24,25). We sought to determine whether the mutant TRs isolated from human RCCCs fit this same pattern and to establish whether the TR mutants from different cancers share a common neoplastic signature that distinguishes them from the RTH TR mutants responsible for endocrine disease.

We report that, in common with their RTH, v-Erb A, and HCC counterparts, most of the RCCC mutants studied can repress but are impaired in T3-mediated transcriptional activation and behave as dominant-negative inhibitors of wt-TRs. For several RCCC mutants, this loss of transcriptional activation reflects, in part, an associated defect in hormone binding; the rc6-TRα1, rc8-TRβ1, and rc25-TRβ1 mutants display a 2- to 70-fold lower avidity for T3 than do the wild-type receptors. Hormone binding, however, is not the sole defect in any of the RCCC mutants tested. This is most clearly observable for rc2-TRα1, which displays a severely weakened transcriptional activity despite binding T3 normally. Similarly, rc6-TRα1 and rc25-TRβ1 display defects in their absolute transcriptional activity that operate in addition to their reduced affinity for T3, resulting in changes in both their EC50 and maximum levels of reporter gene expression in transfection assays. The rc8-TRβ1 mutant achieves virtually wild-type levels of reporter gene activation at very high T3 levels but displays defects in its coregulator interactions in vitro.

Significantly, addition of sufficient T3 allows complete reversal of the dominant-negative phenotype of the two RCCC TRβ1 mutants, a phenomenon we noted previously for two HCC TRβ1 mutants. In contrast, the dominant-negative activity of the RCCC TRα1 mutants was not fully reversed at even the highest T3 concentrations tested; two HCC TRα1 mutants in our previous study also exhibited a T3-refractory dominant-negative phenotype. It will be interesting if this isoform-specific pattern persists as additional mutant receptors are characterized and may suggest that RCCC tumors expressing TRβ1 mutants will be more responsive to the actions of TR agonists than those expressing TRα1 mutants.

These results generally are, with some exceptions, in agreement with the broad conclusions reached from the initial characterizations of the dominant-negative and hormone-binding properties of these mutants (21). Differences between our results and those first published probably reflect differences in the specifics of the assays employed (for example, our use of a DR4 instead of a DIV6 TRE in the DNA-binding assays) (21).

The intrinsic transcriptional defects displayed by the RCCC TR mutants reflect an altered binding to, and release from, corepressors

The ability of the rc2-TRα1, rc6-TRα1, and rc25-TRβ1 mutants to recruit SRC1 was either fully normal or otherwise closely paralleled their T3-binding properties. Many other coactivators are recruited through similar contacts (36,37,38), suggesting that the intrinsic transcriptional defects observed for these RCCC TR mutants cannot be accounted for by impaired coactivator association per se. Instead, a close correlation was observed between the transcriptional defects of these RCCC TR mutants and alterations in their corepressor interactions. The RCCC TR mutants either require substantially more hormone to release from corepressors than predicted from their T3 binding profiles or retain substantial levels of corepressor at T3 levels sufficient to more completely release this corepressor from wild-type receptors.

Furthermore, whereas wt-TRs preferentially bind to NCoR compared with SMRTα (30), many of the RCCC TR mutants bound equally well to both corepressors. This gain in SMRTα recognition was also observed for v-Erb A-TRα1 but is not a signature exclusive to neoplastic TRs; certain RTH TR mutants also exhibit an increased ability to bind to SMRTα vs. NCoR, whereas none of the HCC TR mutants did so. Nonetheless, there are subtle distinctions between cancer- and endocrine-associated mutant TRs that are intriguing, although it will require further analysis to determine their biological significance; for example, the Δ430- and Δ432-TRβ1 RTH mutants display primarily an increased recognition of the S2 CoRNR box, whereas the RCCC and v-Erb A mutants display an enhanced recognition of S1 or both S1 and S2.

We conclude that an increase in corepressor affinity, often coupled to a change in corepressor specificity, is a frequent hallmark of TR mutant-mediated disease. Increases in overall corepressor affinity may serve to enhance the dominant-negative properties of these mutants. Changes in corepressor preference may reflect an adaptation of the mutant TRs to the specific spectrum of corepressors expressed in their respective disease target cells. Alternatively, different corepressors respond to different regulatory kinases (30,33); the observed changes in corepressor specificity may render a mutant TR resistant to cell signals that inhibit repression by wt-TRs.

TR helix 12 functions as a selective gatekeeper and is responsible for corepressor specificity by the wild-type receptor

Receptor helix 12 has been proposed to be a hormone-operated gate that controls corepressor access to a docking surface elsewhere on the receptor by assuming a relatively open conformation in the absence of hormone and by reorienting to occlude corepressor binding in the presence of agonist (27). The TR mutations that change corepressor specificity are all positioned to impact these gatekeeper functions. Among the RCCC mutants, enhanced SMRT binding maps to an M338I substitution in helix 11 in rc2-TRα1 and rc6-TRα1 and to an F451S substitution at the base of helix 12 in rc8-TRβ1; the wild-type amino acids at these positions participate in important contacts between helix 11 and 12 that help stabilize and orient the closed helix 12 conformation. Similarly, the Δ430- and Δ432-TRβ RTH mutants represent deletions that shorten helix 11 and rotate the position of the attached helix 12. V-Erb A-TRα1, and our artificial TRα1-Δhelix12 mutant, delete helix 12 itself. Although not studied here, two RTH TRβ1 mutants, R429Q (immediately preceding helix 12) (39) and the Mkar-TRβ1 mutant (a frameshift that disrupts the last 28 amino acids of TRβ1) (40), also are expected to alter helix 12 and have been shown to associate more strongly with SMRT than with NCoR (29,40).

Our results suggest that the enhanced SMRTα recognition by these mutant TRs results from perturbations in the position of helix 12 that alter access of the corepressor to its docking surface on the receptor. Importantly, these differences in corepressor specificity are observed in the absence of T3, indicating that helix 12 is not simply a hormone-operated switch that either permits or prevents all corepressor binding but is instead a selective gatekeeper that actively discriminates between different forms of corepressor even in its rest position (i.e. in the unliganded receptor). This rest position of the helix 12 gate can be altered by detrimental mutations associated with disease, as shown here, or (potentially) by mutations selected over evolutionary time to adapt a receptor to a particular biological purpose. This may help account for the known differences in corepressor preference seen among the extant nuclear receptors; for example, the wild-type retinoic acid receptor-α encodes a leucine instead of the TR-encoded methionine at the codon 338 position and preferentially binds to SMRTα compared with NCoR (41). Furthermore, given that different receptor agonists and antagonists can impose different conformations on helix 12, it is possible that certain ligands may release only certain members of the NCoR/SMRT corepressor family while retaining or stabilizing the binding of others.

Changes in SMRTα binding reflect changes in TR preference for CoRNR boxes that differ in alternatively spliced versions of corepressor

The enhanced affinity of our helix 11/12 mutants for SMRTα was due to their increased ability to recognize the two most C-terminal CoRNR boxes (S1 and S2) in this corepressor. In contrast, wt-TRs interact weakly with S1 and S2 (accounting for their low affinity for SMRTα) and with N1 and N2 (homologous CoRNR boxes in NCoR) but efficiently recognize NCoR by binding to N3, a third CoRNR box in NCoR that is absent from SMRTα. Notably, the same TR mutations that enhance S1 and S2 binding also enhance N1 and N2 binding, resulting in an enhanced recognition of NCoRδ, an NCoR splice variant lacking N3. Conversely, SMRTγ, a splice variant of SMRT that possesses an S3 CoRNR box in addition to S1 and S2, is, like NCoR, recognized equally well by all mutant and wt-TRs tested. Therefore the mutations in TR helix 11/12 do not alter the receptor preference for the SMRT vs. the NCoR families of corepressors per se but rather for specific splice forms within each family: those that contain CoRNR boxes 1 and 2 vs. those that contain boxes 1, 2, and 3.

TRs associated with neoplasia are typically composites of multiple genetic lesions that work together to produce the mutant phenotype

RTH TR mutants contain a single genetic lesion each, although the specific mutation can differ in different kindreds (11). In contrast, the v-Erb A, HCC, and RCCC mutants are often composed of multiple individual mutations that alter receptor function in myriad ways. For example, the multiple mutations that comprise the rc6-TRα1 mutant, when assayed individually, impaired hormone binding, altered corepressor affinity and specificity, and weakened intrinsic transcriptional activity. Combining these individual lesions may strengthen the repressive, dominant-negative activity of these cancer-related TRs in a synergistic manner not achieved by the single mutations characteristic of endocrine disease.

We previously described a model for TR-mediated oncogenesis that focused on the lesions found in the DNA recognition domains of v-Erb A and HCC TRs; we suggested that these receptors operate in these cancers by misregulating a set of target genes distinct from those usually controlled by the wild-type receptor (24,25). Many of the RCCC TR mutants contain mutations in their DNA-binding domains and therefore fit this generic model. Our present work, however, indicates that many of the RCCC TR mutants also have an enhanced ability to associate with a specific subset of corepressor splice forms as a result of disruptions in receptor helix 12. Although these helix 12 perturbations are not exclusive to TR alleles associated with neoplasia, they may nonetheless contribute to carcinogenesis in association with the other lesions found within the neoplasia-associated receptors, such as those resulting in changes in DNA recognition.

Materials and Methods

Molecular clones

TR mutations associated with human RCCCs, identified previously (21), were recreated within the wt-TR molecular clones using the QuikChange mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. Wild-type or mutant receptors were also subcloned into pFastBac1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using BamH1 and HindIII restriction sites or into a modified pF3A WG (BYDV) Flexi vector (Promega, Madison, WI) using NotI and NheI restriction sites. The pF3A WG (BYDV) Flexi vector was initially cleaved with SgfI and PmeI and ligated with the following annealed oligos to generate an expanded multiple cloning site: 5′-CGCGC GGCCG CAAGC TTCCC GGGCT CGAGG GGCCC GATAT CATCG ATGCT AGCGT TT-3′ and 5′-AAACG CTAGC ATCGA TGATA TCGGG CCCCT CGAGC CCGGG AAGCT TGCGG CCGCG CGAT-3′. The pSG5.2 expression vectors containing human TRα1 and TRβ1, the DR4-thymidine kinase promoter (TK)-luciferase, and the pGEX-MPa-SRC1, pGEX-MPc-SMRT, and pGEX-N-CoR have been described previously (16,24,42,43,44).

GST fusions proteins of individual corepressor CoRNR box containing domains of SMRTγ (S1, amino acids 2303–2508; S2, amino acids 2068–2302; S3, amino acids 1851–2067) and NCoR (N1, amino acids 2249–2453; N2, amino acids 2012–2248; N3, amino acids 1817–2011), and SMRT and NCoR isoforms (SMRTα, amino acids 1851–2470; SMRTγ, amino acids 1851–2509; NCoRδ, amino acids 1817–2334; NCoR, amino acids 1817–2453) were cloned by PCR into the pGEX-KG vector (45) using the following primers: mSMRT S1-up 5′-GATCG AATTC CATAT GATCT TCAAC ATGCC CGCC-3′, mSMRT S1-dn 5′-GATCC TCGAG TCAGT CGACC TCGCT GTCCG AGAGT GTCTC-3′, mSMRT S2-up 5′-GATCG AATTC CATAT GCTAG AGAAG AGCCA CTTGG-3′, mSMRT S2-dn 5′-GATCC TCGAG TCAGT CGACT TCCGT CCCAG GCTGG CC-3′, mSMRT S3-up 5′-GATCG AATTC CATAT GCCCA CGGTC CTGAG GTCC-3′, mSMRT S3-dn 5′-GATCC TCGAG TCAGT CGACC TCTTC CAGAG GTTTG GAGAG C-3′, mNCoR N1-up 5′-GATCG AATTC CATAT GATCT TCAAT CTGCC AGCAG-3′, mNCoR N1-dn 5′-GATCC TCGAG TCAGT CGACG TCGTC ACTAT CAGAC AGTG-3′, mNCoR N2-up 5′-GATCG AATTC CATAT GGTTA AGGCA AATCA AGC-3′, mNCoR N2-dn 5′-GATCC TCGAG TCAGT CGACC TCTGT TCCTG GCTGA GC-3′, mNCoR N3-up 5′-GATCG AATTC CATAT GGGGG GCCCT TCCAT AAGTC-3′, and mNCoR N3-dn 5′-GATCC TCGAG TCAGT CGACG TCTGG CTGAT AGGCC TGTGG-3′. Constructs containing SMRTγ (amino acids 1–2508) (formerly known as SP-18) and NCoRδ (amino acids 1–2334) (formerly RIP13Δ1) were described previously (33) and cloned into appropriate pGEX vectors using restriction endonuclease protocols.

Transient transfection assays, EMSAs, and T3 binding/protease resistance assays

CV-1 cell transfections and dominant-negative assays were performed as described previously (24,46). EMSAs were performed as described previously (24,47) except with the use of TRs expressed from Promega’s TNT coupled wheat germ extract system, in addition to TRs expressed from baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells. Hormone binding was measured as protection from protease degradation in the presence of T3, as previously described (24,26). Briefly, radiolabeled TRs were incubated with increasing concentrations of T3, followed by 0.05 U elastase (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Degradation products were resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE gel and then visualized and quantified by phosphorimager analysis. As confirmation of the applicability of this approach to both mutant and wild-type receptors, we note that at high hormone levels, the mutant TRs reach the same level of protease protection as do the wt-TRs, the size of the protease-resistant core is the same for each mutant as that of the corresponding wt-TR isoform, and the shape and pattern of the protease resistance curves closely parallel one another for all the receptors, differing only in the T3 concentration required for half-maximal protection (supplemental Fig. S1).

In vitro GST pull-down assay

GST fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli using the constructs described above. [35S]Methionine-radiolabeled TRs were synthesized using Promega’s TnT quick-coupled transcription/translation kit. GST pull-down assays were performed as previously described (24,26) using the high-throughput multi-well filter plate system developed previously (48).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Liming Liu for superb technical assistance and Ivan H. Chan and Michael L. Goodson for many helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Public Health Service/National Cancer Institute Award R37-CA53394.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online April 30, 2009

Abbreviations: CoRNR, Corepressor/nuclear receptor interaction; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NCoR, nuclear receptor corepressor; RCCC, renal clear cell carcinoma; RTH, resistance to thyroid hormone; RXRα, retinoid X receptor-α; SMRT, silencing mediator of retinoic acid and TR; SRC1, steroid receptor coactivator-1; TR, thyroid hormone receptor; TRE, T3 response element; wt-TR, wild-type TR.

References

- Yen PM 2001 Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev 81:1097–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CB, Williams GR 2002 Mechanism of thyroid hormone action. Thyroid 12:441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SY 2000 Multiple mechanisms for regulation of the transcriptional activity of thyroid hormone receptors. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 1:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM 1995 The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell 83:835–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lazar MA 2000 The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu Rev Physiol 62:439–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen PM, Cheng SY 2003 Germline and somatic thyroid hormone receptor mutations in man. J Endocrinol Invest 26:780–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SY 2005 Thyroid hormone receptor mutations and disease: beyond thyroid hormone resistance. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:176–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee VK 2001 Resistance to thyroid hormone, and peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor γ resistance. Biochem Soc Trans 29:227–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refetoff S 1993 Resistance to thyroid hormone. Clin Lab Med 13:563–581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen K, Rosenfeld MG 2002 Biological roles and mechanistic actions of co-repressor complexes. J Cell Sci 115:689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen PM 2003 Molecular basis of resistance to thyroid hormone. Trends Endocrinol Metab 14:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sancho JM, García V, Bonilla F, Muñoz A 2003 Thyroid hormone receptors/THR genes in human cancer. Cancer Lett 192:121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow C, Meister B, Lardelli M, Lendahl U, Vennström B 1994 Thyroid abnormalities and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice transgenic for v-erbA. EMBO J 13:4241–4250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld LE, Caldenhoven E, Stunnenberg HG 2001 Avian erythroleukemia: a model for corepressor function in cancer. Oncogene 20:3100–3109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciana P, Braliou GG, Demay FG, von Lindern M, Barettino D, Beug H, Stunnenberg HG 1998 Leukemic transformation by the v-ErbA oncoprotein entails constitutive binding to and repression of an erythroid enhancer in vivo. EMBO J 17:7382–7394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger C, Thompson CC, Ong ES, Lebo R, Gruol DJ, Evans RM 1986 The c-erb-A gene encodes a thyroid hormone receptor. Nature 324:641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sap J, Muñoz A, Damm K, Goldberg Y, Ghysdael J, Leutz A, Beug H, Vennström B 1986 The c-erb-A protein is a high-affinity receptor for thyroid hormone. Nature 324:635–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Chen S, Zhu XG, Shieh H, McPhie P, Cheng S 1997 The gene regulating activity of thyroid hormone nuclear receptors is modulated by cell-type specific factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 238:280–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KH, Shieh HY, Chen SL, Hsu HC 1999 Expression of mutant thyroid hormone nuclear receptors in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Carcinog 26:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KH, Zhu XG, Hsu HC, Chen SL, Shieh HY, Chen ST, McPhie P, Cheng SY 1997 Dominant negative activity of mutant thyroid hormone α1 receptors from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Endocrinology 138:5308–5315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya Y, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, McPhie P, Nauman J, Cheng SY, Nauman A 2002 Expression of mutant thyroid hormone nuclear receptors is associated with human renal clear cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 23:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Krystyniak A, Madej A, Cheng SY, Nauman J 2002 Functionally impaired TR mutants are present in thyroid papillary cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1120–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CS, Lin KH, Hsu YC 2002 Alterations of thyroid hormone receptor α gene: frequency and association with Nm23 protein expression and metastasis in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett 175:121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan IH, Privalsky ML 2006 Thyroid hormone receptors mutated in liver cancer function as distorted antimorphs. Oncogene 25:3576–3588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Privalsky ML 2005 Multiple mutations contribute to repression by the v-Erb A oncoprotein. Oncogene 24:6737–6752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farboud B, Privalsky ML 2004 Retinoic acid receptor-α is stabilized in a repressive state by its C-terminal, isotype-specific F domain. Mol Endocrinol 18:2839–2853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privalsky ML 2004 The role of corepressors in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Annu Rev Physiol 66:315–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RN, Brzostek S, Kim B, Chorev M, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN 2001 The specificity of interactions between nuclear hormone receptors and corepressors is mediated by distinct amino acid sequences within the interacting domains. Mol Endocrinol 15:1049–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RN, Putney A, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN 2000 The nuclear corepressors recognize distinct nuclear receptor complexes. Mol Endocrinol 14:900–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson M, Jonas BA, Privalsky MA 2005 Corepressors: custom tailoring and alterations while you wait. Nucl Recept Signal 3:e003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood TN, Adams M, Tone Y, Chatterjee VK 1994 Spectrum of transcriptional, dimerization, and dominant negative properties of twenty different mutant thyroid hormone β-receptors in thyroid hormone resistance syndrome. Mol Endocrinol 8:1262–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoh SM, Privalsky ML 2000 Resistance to thyroid hormone (RTH) syndrome reveals novel determinants regulating interaction of T3 receptor with corepressor. Mol Cell Endocrinol 159:109–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas BA, Varlakhanova N, Hayakawa F, Goodson M, Privalsky ML 2007 Response of SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor) and N-CoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) corepressors to mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase cascades is determined by alternative mRNA splicing. Mol Endocrinol 21:1924–1939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski A, Brzostek S, Cohen RN, Hollenberg AN 2003 Determination of nuclear receptor corepressor interactions with the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 17:273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb P, Anderson CM, Valentine C, Nguyen P, Marimuthu A, West BL, Baxter JD, Kushner PJ 2000 The nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR) contains three isoleucine motifs (I/LXXII) that serve as receptor interaction domains (IDs). Mol Endocrinol 14:1976–1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo C, Chen JD 2000 The SRC family of nuclear receptor coactivators. Gene 245:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, Xu J, Nawaz Z, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW 1999 Nuclear receptor coactivators: multiple enzymes, multiple complexes, multiple functions. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 69:3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW 2002 Nuclear receptor coactivators: an update. Endocrinology 143:2461–2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M, Matthews C, Collingwood TN, Tone Y, Beck-Peccoz P, Chatterjee KK 1994 Genetic analysis of 29 kindreds with generalized and pituitary resistance to thyroid hormone. Identification of thirteen novel mutations in the thyroid hormone receptor β gene. J Clin Invest 94:506–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Cohen RN, Simsek E, Senses DA, Yar NE, Grasberger H, Noel J, Refetoff S, Weiss RE 2006 A novel thyroid hormone receptor-β mutation that fails to bind nuclear receptor corepressor in a patient as an apparent cause of severe, predominantly pituitary resistance to thyroid hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1887–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farboud B, Hauksdottir H, Wu Y, Privalsky ML 2003 Isotype-restricted corepressor recruitment: a constitutively closed helix 12 conformation in retinoic acid receptors β and γ interferes with corepressor recruitment and prevents transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol 23:2844–2858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CW, Privalsky ML 1998 Transcriptional silencing is defined by isoform- and heterodimer-specific interactions between nuclear hormone receptors and corepressors. Mol Cell Biol 18:5724–5733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas BA, Privalsky ML 2004 SMRT and N-CoR corepressors are regulated by distinct kinase signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 279:54676–54686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson ML, Jonas BA, Privalsky ML 2005 Alternative mRNA splicing of SMRT creates functional diversity by generating corepressor isoforms with different affinities for different nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem 280:7493–7503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan KL, Dixon JE 1991 Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: an improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal Biochem 192:262–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoh SM, Chatterjee VK, Privalsky ML 1997 Thyroid hormone resistance syndrome manifests as an aberrant interaction between mutant T3 receptors and transcriptional corepressors. Mol Endocrinol 11:470–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Privalsky ML 2005 Heterodimers of retinoic acid receptors and thyroid hormone receptors display unique combinatorial regulatory properties. Mol Endocrinol 19:863–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson ML, Farboud B, Privalsky ML 2007 An improved high throughput protein-protein interaction assay for nuclear hormone receptors. Nucl Recept Signal 5:e002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.