Abstract

Background/Objective:

Outcomes research of therapeutic recreation (TR) activities and interventions for spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation is made more difficult by a lack of uniform descriptions and the absence of a formal treatments classification system (taxonomy). The objective of this study was to describe a taxonomy developed by Certified Therapeutic Recreation Specialists.

Methods:

TR lead clinicians and researchers from 6 SCI rehabilitation centers developed a TR documentation system to describe the details of each TR session involving patients with SCI enrolled in the SCIRehab study. The SCIRehab study uses the practice-based evidence methodology, a rigorous observational methodology that examines current practice without introducing additional treatments, to capture details of each TR session for 1,500 SCI rehabilitation patients at 6 US inpatient SCI rehabilitation facilities. This may be the first attempt to document the many details of the TR rehabilitation process for patients with SCI.

Results:

The TR taxonomy consists of 6 activities (eg, leisure education and counseling, outings, and leisure skill work in center) and activity-specific interventions, as well as time spent on each activity. Activity descriptions are enhanced with additional details that focus on assistance needs for each activity, patient ability to direct care, and patient/family involvement, which may help to determine TR activity selection.

Conclusion:

Development and application of a TR taxonomy, which is comprehensive for patients with SCI and efficient to use, are feasible despite significantly different TR programs at the 6 SCIRehab centers.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Rehabilitation, Therapeutic recreation, Outcomes research, Taxonomy, Practice-based evidence, Functional Independence Measure

INTRODUCTION

The primary responsibility of therapeutic recreation (TR) for patients with recent spinal cord injury (SCI) is to assess the preinjury leisure lifestyle, develop goals, and implement a treatment plan that facilitates the patient's return to an independent, active, and healthy lifestyle. TR goals may include exposure to new leisure options, exploration of adaptive equipment and modifications to previously enjoyed or new leisure options, leisure counseling and education, and community reintegration. Although practicing clinicians believe TR makes a substantial contribution to SCI rehabilitation, little evidence is available to show the effectiveness of the techniques used by Certified Therapeutic Recreation Specialists (CTRSs). Few guidelines exist to define best clinical TR practices when treating SCI and the field does not agree on terminology for uniformly describing or quantifying TR activities in which patients participate or the interventions used by therapists to facilitate the activities.

This was the situation facing the CTRSs who were preparing for data collection in SCIRehab, a study of outcomes associated with the acute rehabilitation process after SCI.

In 1991, Riley (1) noted that “the need to establish valid outcome measures and a reliable monitoring system is critical to the growth and continued acceptance of therapeutic recreation.” Nearly 2 decades after Riley's observation, it seems little growth has occurred in the field of TR with regard to outcome measurement. In 2007, Keogh Hoss and McCormick (2) concluded that “the field continues to lack abilities to demonstrate the provision of outcomes.”

Despite the many challenges still facing the TR research and clinical community, some investigators are making progress to improve the body of scientific literature within the field. Tasiemski et al (3) reported that persons with SCI who were involved in physical activities, including sports, showed greater satisfaction with life than those not participating in physical recreation. Kleiber and Brock (4) found that leisure activities and, in particular, constraints placed on leisure activities, can play an important role in the definition of one's self. This notion is pivotal to the discussion of the role of TR for persons with SCI, because preferred leisure pursuits may be eliminated or require modification after injury. Noreau and Fougeyrollas (5) found significant disruptions in the areas of recreational and physical activities after injury. Together, these studies suggest that assisting a person to renew leisure activities after SCI can help to develop a new concept of self that could lead to greater life satisfaction. Noreau and Shepherd (6) suggested that physiologic improvements can be gained by people with SCI who engage in fitness programs. They recommended that SCI rehabilitation settings incorporate programs that include structured exercise conditioning. CTRSs have the chance to expose patients to opportunities to participate in recreational activities that promote fitness, particularly for the SCI population.

Several attempts have been made to categorize leisure interests and activities. A recent examination of the literature by Tinsley and Eldredge (7) showed the insufficiencies in previously developed classifications of leisure activities. One approach classified leisure activities into 9 groups based on the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (8), and another developed a classification based on Holland codes (9). Holland codes classify personality types into 6 categories: realistic, conventional, enterprising, social, artistic, and investigative. Although originally developed for use in classification of vocational preferences, these personality codes have since been combined into a tool called the Leisure Activities Finder (9). Other approaches attempted to classify leisure based on survey results either by individuals rating the frequency of their participation in or their interest in various leisure activities (7). All of these classifications have either failed empirical tests, have never been tested, or used methods that produced inconclusive results. In response, Tinsley and Eldredge (7) proposed and developed a classification of leisure activities based on need-gratifying properties. Their survey was conducted primarily with college students, and many of the items examined were perhaps more relevant to people without a physical disability. However, the study “demonstrate[s] that participation in leisure activities satisfies important psychological needs such as those for affiliation, enhancement, self-expression, nurturance, and sensibility…” (7). Although this study was conducted with subjects without disabilities, the correlation between use of spare time and psychologic needs is presumably equally true of people with SCI who may need to modify previous forms of leisure or find new activities.

A working group at the American Therapeutic Recreation Association (ATRA) Curriculum Conference in 1995 assembled a classification of 23 TR modalities and 21 facilitation techniques used by CTRSs. Modalities included activities such as activities of daily living (ADLs), athletics, and games; facilitation techniques included methods such as family involvement, leisure education, and social skills training. The resulting guidelines and curriculum guide is available for ATRA members through the ATRA website (10). Although this classification is fairly comprehensive, it encompasses the work of therapists in a variety of settings (eg, geriatric care and mental health) but is not specific to SCI rehabilitation.

Although there have been many attempts to develop taxonomies of leisure activities and ATRA has begun the process of developing a classification system, none of these adequately represent the unique role of TR in a SCI rehabilitation setting.

SCIREHAB PROJECT

The SCIRehab Project, a 5-year research study, will enroll 1,500 consecutive initial acute rehabilitation admissions of patients with traumatic SCI consenting to participate at 6 centers. The study is designed to determine which SCI rehabilitation activities and interventions are associated most strongly with positive outcomes at 1 year after injury for specific types of patients with SCI. In the first article in this series, Whiteneck et al (11) describes the SCIRehab study in greater detail, including the importance of center-to-center practice differences for the practice-based evidence (PBE) methodology, and presents the overall study hypotheses (11).

The second article, by Gassaway et al (12), describes in detail the iterative process used to develop discipline-specific treatment taxonomies and details those elements that are common across disciplines (eg, TR, physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychology) in the SCIRehab project, such as patient assistance needs, patient/family involvement, and factors impacting a given treatment session.

The purpose of this article is to describe the TR taxonomy developed by the group of CTRSs and to explain the elements that were included. Center-by-center practice differences among the 6 SCIRehab centers are more pronounced in TR than perhaps any other discipline. Thus, to be applicable in each center and to provide a complete and accurate picture of TR's contribution to SCI rehabilitation care, the resulting TR taxonomy is comprehensive of TR activities and interventions used at each center. For example, in only 1 center do CTRSs take patients hot air ballooning; several centers focus on skill-based outings; and other centers focus almost exclusively on outings to recreational venues (eg, professional sporting events, the zoo).

TAXONOMY

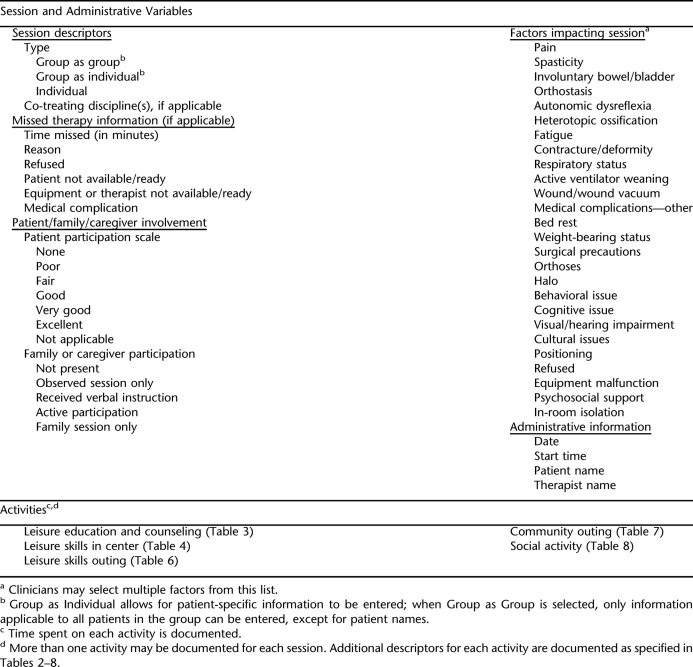

The format of the TR documentation (including taxonomic information) is consistent with the layout used in the documentation of other SCIRehab disciplines; it captures general session information and activity-specific details performed in the session. Table 1 provides an overview of the menu-driven TR documentation system. The CTRS first describes the session in terms of type (individual or group), co-treatment with other disciplines (if applicable), and extent of patient and family involvement. Factors that may limit the session (eg, orthostasis or behavioral issues) are identified. The CTRS then identifies 1 or more TR activities in which the patient participates during the session. Each of these activities is described in the taxonomy section below.

Table 1.

TR Activities and Session Variables

Although all disciplines in the SCIRehab study document each session as an individual or a group session, as described in the article by Gassaway et al (12), TR uses a slightly different approach for how clinicians assign a group or individual type to each session. Other SCIRehab disciplines allow for 2 documentation options for group therapy: Group as Group and Group as Individual for all group work. The Group as Group option allows the clinician to document information for all patients in the group with a single session entry (documentation for all patients in the group is the same) and simplifies documentation for the clinician; however, patient-specific information is not captured when this option is selected. Because of the importance of group work in TR, the Group as Group documentation option is limited to 3 TR activities: leisure education and counseling, leisure skills in center, and social activity. Selection of the Group as Group option is limited further to when hands-on instruction does not take place and the type of education approach is the same for all patients in the group. All outings, regardless of how many patients participate, must be documented as Group as Individual, which provides the same patient-specific information about treatment details, assistance needs, participation level, family involvement, and individual patient factors that impact the session that is included for an individual patient session.

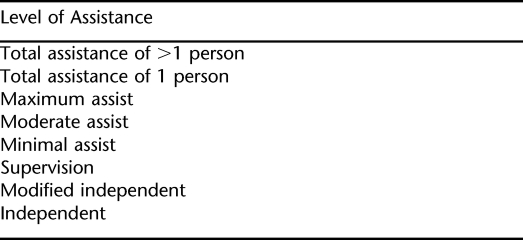

Table 2 lists the adapted Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scale used to identify the level of assistance (LOA) that patients need to perform the activities included in the TR taxonomy. The 7-point FIM descriptor scale is used because CTRSs at several SCIRehab centers use this nomenclature to describe their patients' assistance needs. In addition to identifying assistance needs for each specific leisure skill, the CTRS documents overall assistance needs required for participation in out-of-center outings. If the outing includes performance of a leisure skill, the clinician documents overall LOA for the outing and LOA for the specific skill. For example, if a patient goes on an outing to a bowling alley, the CTRS documents the LOA needed for the leisure skill of bowling and then documents the LOA the patient requires for the outing as a whole.

Table 2.

Options for the Level of Assistance Descriptors

Each activity included in the TR taxonomy is described below along with the therapeutic interventions used for each activity:

Leisure Education and Counseling

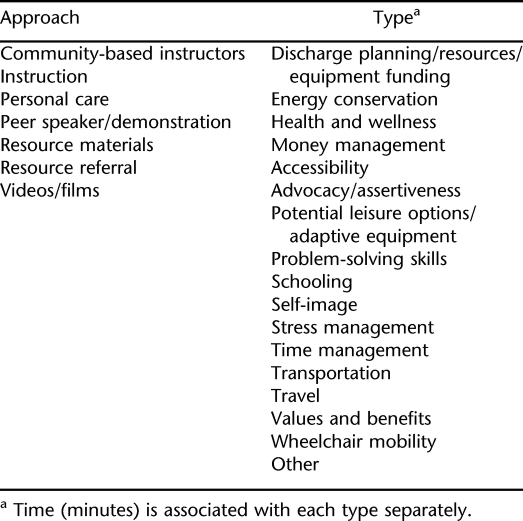

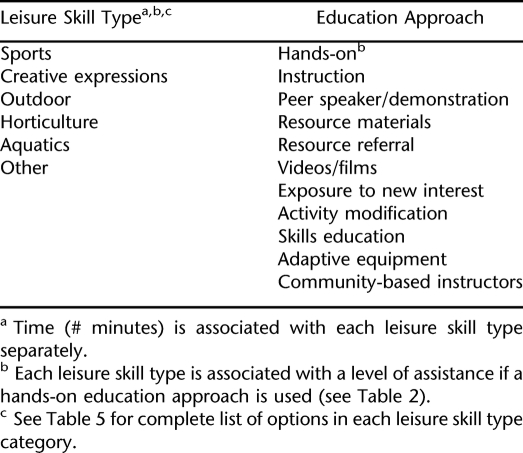

“Leisure education provides individuals [with a disability] the opportunity to enhance the quality of their lives in leisure; understand opportunities, potentials, and challenges in leisure; understand the impact of leisure on the quality of their lives; and gain knowledge, skills, and appreciation enabling broad leisure skills” (13). In physical rehabilitation, leisure education and counseling provide individuals with the necessary skills to initiate and participate in leisure activities when they return to the community. There are many barriers to leisure participation that an individual is able to overcome with education, skill training, and resources. Common barriers include decreased awareness of potential leisure options, lack of transportation options, lack of knowledge of adaptations/modifications and resources, fear of social stigma, limited wheelchair skills, and decreased motivation. Leisure education/counseling sessions address these barriers and limitations to facilitate a successful community reentry. The Leisure Education and Counseling activity in the TR taxonomy includes the subject matter of the education/counseling provided (eg, accessibility) and the approach(es) used to facilitate leisure education counseling (eg, use of community-based instructors; Table 3). It does not include education about specific leisure skills (eg, sports, music, gardening); these are included in the leisure skills in center activity.

Table 3.

Leisure Education and Counseling

Leisure Skills in Center

All individuals have leisure activities that they enjoy; a SCI can affect the ability to perform these activities. Leisure skill exploration is an integral TR component of SCI rehabilitation. Leisure skill interventions involve education alone or a combination of education and hands-on training. The goal of leisure skill exploration is to provide individuals with the skills and knowledge needed to pursue existing or new interests after discharge.

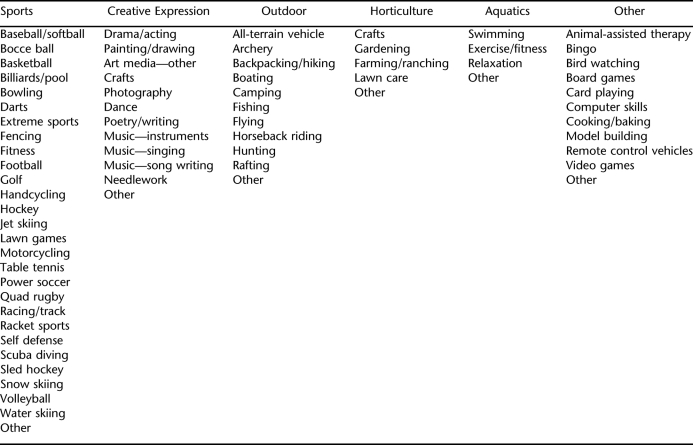

The TR taxonomy organizes leisure skill types in 6 main categories: sports, creative expression, outdoor, horticulture, aquatics, and other (Table 4). Each leisure skill type uses a comprehensive list of subtopics (for instance, the sports category includes hand cycling, basketball, rugby) as shown in Table 5. These subtopic lists are lengthy because of practice differences at each site and the scope of services provided. For each identified leisure skill type, the CTRS documents the amount of time spent on the specific skill, the method(s) of education used to work with the patient on the skill, and the level of assistance the patient needs to complete the skill if a hands-on approach is used (Table 4). If a patient explores more than 1 leisure skill during a session, the CTRS documents the above listed information for each skill.

Table 4.

Leisure Skills in Center

Table 5.

Options for the Leisure Skill Type Descriptors

Outings

TR-initiated outings into the community, as well as simulated outings that occur on-campus, serve multiple goals. Patients who experience trips away from the facility work on problem solving in the community (eg, accessibility issues, money management, and door management). Outing participation allows for carryover or reinforcement of skills learned in the center (eg, mobility, feeding, and personal care). Additionally, participation in outings provides the opportunity for the patient to venture into the community in a safe setting and address the many psychosocial issues involved with community re-entry. Outings can increase awareness of potential leisure options, as well as the associated challenges that can be encountered in the community.

The TR taxonomy captures 2 types of outings: those associated with learning or performance of a leisure skill and those that involve going to a specific venue for enjoyment and community exposure.

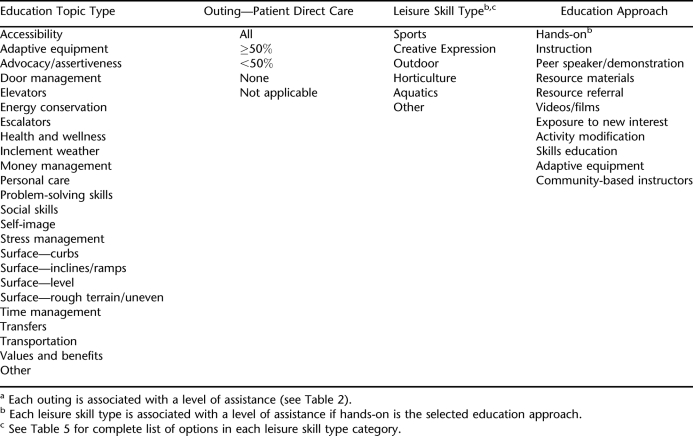

Leisure Skill Outings

Patients may participate in outings that involve leisure skills that they enjoyed before injury or that explore alternative leisure skill activities that may interest them after discharge from the rehabilitation center. The TR taxonomy is used to document work in specific skill areas. Table 6 depicts leisure skill types and education approaches that are similar to those that describe leisure skill work that is done within the rehabilitation center (Table 4). In addition, education topics that may be worked on during an out-of-center outing are described. The CTRS indicates whether the patient is able to direct his/her own care and the LOA that is needed for each leisure skill type practiced on the outing and for the outing in general.

Table 6.

Leisure Skills Outinga

Community Outings

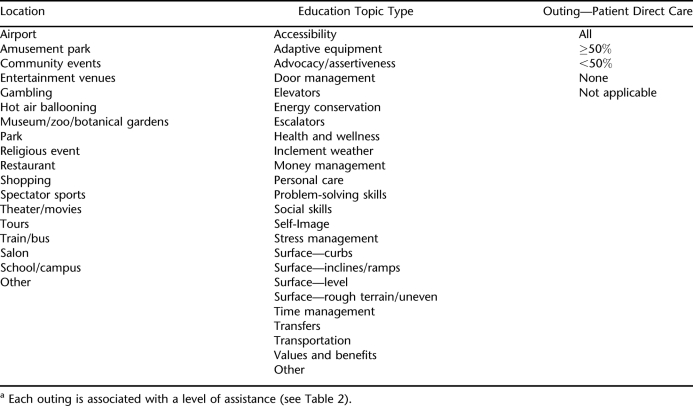

Often, CTRSs take patients on outings to recreational venues that do not involve participation in a specific leisure skill. Table 7 contains a comprehensive list of outing locations used by the SCIRehab centers. CTRSs document the location of the outing and, similar to leisure skill outings, the education topics covered on the outing (eg, accessibility, money management, energy conservation, self-image, personal care). Assistance needs and patient ability to direct care are included for this type of outing also.

Table 7.

Community Outinga

In several SCIRehab centers, multidisciplinary outings, which assist with community re-entry for patients, are common. Comprehensive SCIRehab documentation for these outings is the responsibility of the TR staff. The other disciplines taking part in the excursion document information specific to their goals/objectives for the outing (eg, the occupational therapist documents specific details about ADL work [feeding, toileting, etc] as it occurred).

Social Activity

Patients sharing experiences in a social setting can lead to exchanges of encouragement, positive support, and lasting friendships, all factors that can have an effect on the rehabilitation process. It is recognized that social events may occur outside the supervision of TR; the TR taxonomy captures only organized social activities (Table 8). More details are not included because patients are free to come and go, and the social activity may be supervised by a variety of individuals (peer mentors, volunteers, CTRSs, etc).

Table 8.

Social Activity

DISCUSSION

Program Variation

Each of the 6 SCIRehab centers has a TR Program; however, significant differences exist in the approach to TR among the centers. One center has 18 CTRSs and is able to offer a wider range of therapeutic activities and interventions. Another center has only 1 CTRS and uses large social events, which do not require hands-on assistance by a CTRS, to reach more patients (eg, in-center movie viewings, bingo, performances). Some centers offer multiple outings per week, whereas others have more limited options. In-center offerings also differ; some have a pool, basketball courts, etc, on campus, which makes exploration of and participation in these activities more feasible. Third party and hospital insurance policies may limit the types of community exposure TR is able to provide to patients (eg, overnight camping, riding on all-terrain vehicles, and other more extreme leisure options).

Length of stay (LOS) is another factor that influences the variety and quantity of services TR is able to provide. LOS varies among the SCIRehab centers, and thus, the continuum of services provided can be quite different. For SCIRehab centers with a shorter average LOS (3–4 weeks for patients with paraplegia and 89 weeks for patients with tetraplegia), TR interventions must be geared toward the most immediate goal of helping prepare patients for discharge and re-entry in the community. Initial emphasis is placed on the assessment of patient needs and areas of interest. Education is provided about leisure options (eg, card playing, cycling, or gardening), but the time to participate may be limited. In SCI centers with a longer LOS, there are more opportunities for TR to advance beyond initial assessment of leisure interests and basic education to providing hands-on participation. Exposure to and participation in a variety of activities helps patients identify leisure interests they might want to pursue after discharge from the rehabilitation center.

Comprehensive Taxonomy

The different approaches to TR at the SCIRehab centers necessitated a comprehensive documentation tool that incorporated all of the centers' scopes of service. While developing their comprehensive documentation, the TR lead clinicians were cognizant of the need to maintain a balance between collecting sufficient details to demonstrate variations in treatment approaches and not collecting so much detail that clinicians would feel the documentation expectations were too burdensome. The lead CTRSs included detailed data about each TR activity in each session so that TR interventions could be associated with outcomes. In doing so, they were led by a number of specific questions. Does exposure to a specific leisure skill impact participation in that skill after discharge? Does the level of assistance needed for participation in a leisure skill or social outing impact carryover after discharge? Answers to these questions are dependent on detailed data, and thus, the TR taxonomy includes sometimes lengthy lists of options to describe the specific skills taught or practiced, the education topics discussed/practiced, and the educational approaches used. Although these lists may look overly long, clinicians find it easy to scan the option lists and record the applicable session information.

TR places a high value on community re-entry and is the primary discipline to plan outings throughout a patient's stay in the inpatient rehabilitation hospital. Although much TR work may be done in the hospital gym, the “heart” of TR labor focuses on efforts to take patients into the community to begin to build the confidence needed to participate in community-based activities after discharge. Consistent TR documentation using the Group as Individual documentation option for all types of outings (including multidisciplinary ones) provides a framework to provide patient-specific details such as assistance needs, patient and family participation, and the amount of care a patient is able to direct. These aspects of outings may affect carryover of the recreation activity after discharge and have significant associations with outcomes at 1 year after injury.

Taxonomy Usefulness

A concern of the clinical leaders, however, is that the 1-year postinjury follow-up time frame used in the SCIRehab study (11) may not be of sufficient length to capture a patient's long-term outcomes related to recreational activities. Often, recreation is not a primary focus in the early phases after discharge. The patient and family frequently concentrate on establishing a routine, continuing with therapy on an outpatient basis, obtaining equipment and medical supplies, and handling medical issues. Patients continue to work on increasing their strength, endurance, and functional abilities, which may be needed to pursue certain recreational interests. To the degree that recreational pursuits are seasonal (outdoor gardening, adapted skiing, etc), the follow-up period of 1 year after injury may also be too short. Because patients may not be fully engaged in their recreation lifestyle, an additional follow-up (eg, at 2 or 3 years after injury) might be beneficial to examine the relationship between the intensity and/or extent of exposure to recreational activities during inpatient rehabilitation and those pursued once a patient has re-established a community lifestyle.

DeJong et al (14) outlined criteria that define the usefulness of taxonomy efforts. Several of these points were considered in development of the TR taxonomy. Using the PBE approach and relying primarily on the expertise and experience of clinicians, this taxonomy was designed to capture a comprehensive description of TR activities and interventions within the SCI rehabilitation setting. TR is a multidimensional field encompassing various outing locations and leisure skills as well as leisure education, patient involvement (eg, hands-on or instruction), and the development of functional skills within the community (eg, managing doors or sidewalk curbs). The TR taxonomy for SCIRehab incorporates all of these and organizes them according to relevance within each activity. The use of an electronic data capture method (12) provides a reliable, efficient, and minimally burdensome method to capture data within the busy schedule of TR clinicians. Furthermore, the activity categories are broad, allowing for simple addition of new TR methods as growth in the field continues. Of course, the specificity required to ensure a complete picture of TR in the SCI rehabilitation setting does limit the scope of this particular taxonomy; however, it could provide a schema for the development of a treatment classification in other TR realms such as geriatric or mental health programs.

CONCLUSIONS

Research utility of the taxonomy will be explored when data collection is complete and the SCIRehab analyses attempt to relate TR processes to outcomes. At a time when rehabilitation centers use TR services differently and rehabilitation reimbursement is under review, showing the link between taxonomy details and patient outcomes also may justify the value of TR.

Footnotes

The contents of this article were developed under grants from the Department of Education and NIDRR Grants H133A060103 and H133N060005 to Craig Hospital, H133N060028 to National Rehabilitation Hospital, H133N060009 to Shepherd Center, and H133N060014 to Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

This is the 5th in a series of 9 articles describing The SCIRehab Project: Classification of SCI Rehabilitation Treatments.

REFERENCES

- Riley B, editor. Quality Assessment: The Use of Outcome Indicators, Quality Management: Applications for Therapeutic Recreation. State College, PA: Venture Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh Hoss M, McCormick B. Survey to identify quality indicators for recreational therapy practice. Annu Therap Recreation. 2007;XV:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tasiemski T, Kennedy P, Gardner B, Taylor N. The association of sports and physical recreation with life satisfaction in a community sample of people with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation. 2005;20(4):253–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiber D, Brock S. The relevance of leisure in an illness experience: realities of spinal cord injury. J Leis Res. 1995;27(summer):283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P. Long-term consequences of spinal cord injury on social participation: the occurrence of handicap situations. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22(4):170–180. doi: 10.1080/096382800296863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noreau L, Shephard R. Relationship of impairment and functional ability to habitual activity and fitness following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res. 1993;16(4):265–275. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley H, Eldredge B. Psychological benefits of leisure participation: a taxonomy of leisure activities based on their need-gratifying properties. J Couns Psychol. 1995;42(2):123–132. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor. Dictionary of Occupational Titles. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg K, Rosen D, Holland J, editors. Leisure Activities Finder™ (LAF). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney T, Whitman J. Guidelines for Competency Assessment and Curriculum Planning in Therapeutic Recreation: A Tool for Self-Evaluation. Hattiesburg, MS: American Therapeutic Recreation Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteneck G, Gassaway J, Dijkers M, Jha A. New approach to study the content and outcomes of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: The SCIRehab Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):251–259. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassaway J, Whiteneck G, Dijkers M. Clinical taxonomy development and application in spinal cord injury research: The SCIRehab Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):260–269. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumbo N, editor. Inclusive Leisure Services: Responding To the Rights of People With Disabilities. 2nd ed. State College, PA: Venture Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong G, Horn S, Gassaway J, Slavin M, Dijkers M. Toward a taxonomy of rehabilitation interventions: using an inductive approach to examine the “black box” of rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]