Abstract

Context:

Spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation nurses document the occurrence of educational and care management efforts in traditional nursing documentation methods but not the intensity (or dose) of such interactions. This article describes a process to capture these nursing interventions.

Methods:

Nurses at 6 US inpatient SCI centers used 2 in-person meetings and weekly telephone calls over 9 months to develop a taxonomy of nursing patient education efforts and care management.

Results:

This was subsequently incorporated into a point-of-care documentation system and used to capture details of nursing care for 1,500 SCI rehabilitation patients enrolled in the SCIRehab study. The taxonomy consists of 10 education and 3 care management categories. The point-of-care system includes time spent on each category along with an indication of whether the patient and/or family received the education/care management. In addition, a subjective measure of patient participation in nursing activities is included.

Conclusions:

Creation of a SCI rehabilitation nursing taxonomy is feasible, and its use has had an impact on nursing practice. It also has implications for future clinical documentation, because greater accuracy and details of patient education and care management will be a permanent practice in the participating systems at the conclusion of the study.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries; Rehabilitation, physical; Nursing; Patient education; Taxonomy; Practice-based evidence

INTRODUCTION

Nursing is recognized as an integral member of the interdisciplinary team providing inpatient rehabilitation for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI). Rehabilitation nurses in acute SCI inpatient settings provide a myriad of interventions, including direct patient care, collaborative medical care, patient and caregiver education, care management, and psychosocial support for patients and families. They carry over what was done in the therapies, including practice and reinforcement of such activities as bed mobility, transfers, and activities of daily living (ADLs). Yet despite the substantial contributions of nurses to the rehabilitation of individuals with SCI, there is a dearth of information to document nursing interventions in SCI rehabilitation and their impact on patient outcomes. Additionally, the specialty practice of rehabilitation nursing lacks standards of care for nursing interventions for individuals receiving rehabilitation for SCI. Furthermore, although there are taxonomies of nursing care interventions and outcomes documented in the literature, no formal taxonomy exists to specifically describe rehabilitation nursing or SCI nursing interventions and outcomes.

BACKGROUND

Although there is a tremendous amount of literature related to nursing care of patients with SCI, there is a paucity of literature that focuses on how nursing care during rehabilitation influences outcomes, including length of stay, complications, and quality of life. The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine identified 4 domains of outcomes for patients with traumatic SCI: motor recovery, functional independence, social integration, and quality of life (1). Nursing interventions perhaps have the most significant impact in the domains of functional independence, social reintegration, and quality of life. In a qualitative study that examined how the nursing role is perceived in SCI rehabilitation (2), Pellatt concluded that patients value nurses' contributions more as a means of emotional and physical support and less as a serious input in the rehabilitation process. Nurses saw themselves as the “bedrock” of rehabilitation, although some felt that nursing might be perceived as the “low-profile aspect of rehabilitation” (2).

The patients in this study felt that “rehabilitation was therapy, with nursing care appearing to be compartmentalized into something complementary to rehabilitation rather than a rehabilitation intervention in its own right” (2). However, patients identified nurses as their main source for learning skin care, medication, and bladder management and acknowledged the nurse as being the core professional who has a global perspective on the rehabilitation program. Nurses were seen as the first point of contact for the rehabilitation patient and as the team members who gave them most of the information they needed during their hospitalization. This may be an invaluable, although unrecognized, advantage that nurses might have in influencing patient learning and, ultimately, in affecting patient outcomes.

May et al (3) examined education of the patient with SCI with regard to the domains of knowledge, problem solving, and perceived importance of the information that is taught. They concluded that even though a patient may perceive a topic as important, increased knowledge did not necessarily translate into better problem-solving capabilities. They suggest that this might indicate the need to interject active learning strategies into program curricula to accomplish knowledge transfer in everyday situations.

May and colleagues suggest that it might be “difficult to implement within a lecture format of teaching” the learning principle of the adult as independent learner (3). Although group learning develops the patient's knowledge base, the “active” learning necessary for cementing concepts and tasks is less attainable in the traditional classes that most programs utilize. In Pellatt's study, patients attested to the efficacy of nurse interaction in their learning process (2).

Ralph et al define outcomes of nursing practice as “those end products of the nursing care process that can be linked to specific structural and procedural nursing-sensitive variables” (4). They also state that nursing-sensitive outcomes for SCI provide a system for measuring the quality of nursing care and present the basis for improved care. In this study, which aimed to examine nursing-sensitive outcomes in patients with SCI, bowel elimination and urinary elimination were ranked as the top 2 nurse-sensitive outcomes as perceived by experienced SCI nurse clinicians. These were followed by ambulation and tissue integrity. The authors suggest that these 4 outcomes strongly relate to individuals' ability to provide or direct self-care and enable them to be independent.

In the study by May, patients consistently ranked bladder, bowel, and skin care as highly important to them during their rehabilitation (3). Nurses are in the unique position to mold behavior through teaching and reinforcing actions that are important in the areas of bladder, bowel, and skin, as well as complementing and supporting the education on which other interdisciplinary team members focus their interventions.

Olinzock undertook a qualitative study to develop a model for assessment of learner readiness for self-direction of care in individuals with SCI (5). This model addresses levels of dependency of the patient (from dependent to self-direction) and role of the nurse from authority to consultant. Although this model has not been tested widely, the fundamental premise of the model lies in the concept of patient engagement. The assumption is that as patient engagement increases, so does readiness to learn and therefore movement towards independence in self-directed care. Patient engagement is characterized as a dynamic and selective process, with the role of the nurse to surrender control of patient care as the patient moves towards independence in self-directed care (5).

SCIRehab Project

The SCIRehab Project is a 5-year research effort designed to determine which SCI rehabilitation interventions, including nursing interventions, are associated most strongly with positive outcomes at 1-year after SCI. Outcome measures include functional independence, medical complications, rehospitalizations, social integration, and quality of life. The first article on SCIRehab in this series describes the SCIRehab study in greater detail and sets forth the importance of the practice-based evidence methodology utilized in this study (6).

Gassaway et al (second article in this series) (7) outlines the multiple data sources being used to obtain project data, including the medical record. Although other disciplines were not confident that reliable, detailed intervention data would be present in traditional documentation, such as the medical record, nursing leaders from the 6 participating centers were convinced that most nursing-related intervention data, including information on skin assessment/wound care, bladder management, and bowel management, were contained in nursing care narrative notes, flow sheets, and other forms of nursing documentation. The nurse leaders acknowledged practice differences among the 6 participating centers relative to these fundamental nursing care practices but were confident that practices were described adequately in existing nursing documentation. However, they did recognize there were 2 key areas of nursing interventions that were not documented adequately in traditional nursing records: (a) time spent by nurses in direct patient education on various topics and (b) time spent by nurses in the care management process (differentiated from “case management” described below). Therefore, the decision was made to augment traditional nursing documentation with point-of-care documentation in these two areas.

Nursing Taxonomy

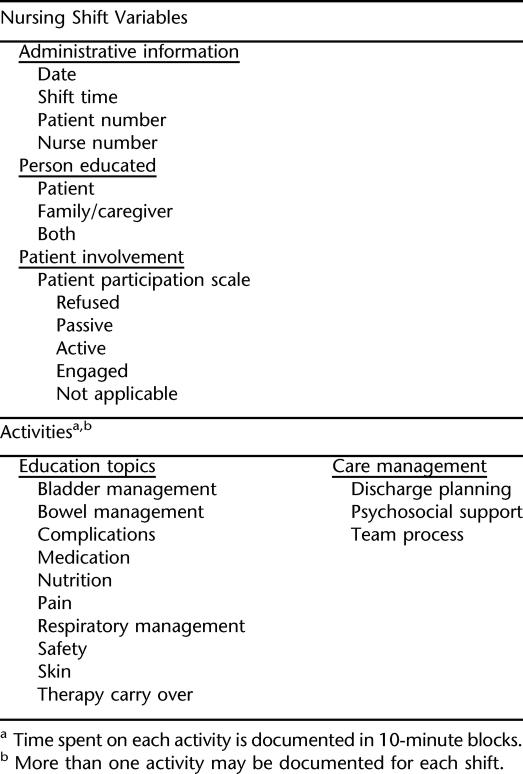

The format used for supplemental nursing documentation of nursing education and care management is consistent with the format used in other SCIRehab discipline documentation in that it includes taxonomic information (interventions) and shift-level variables (session level for other disciplines), including a rating of patient participation (Table 1). The term taxonomy, as used to describe nursing information in the SCIRehab study, refers to patient education and care management activities only. This contrasts with other disciplines' use of the term, in which taxonomy is a comprehensive compilation of all interventions for patients with SCI. The general taxonomy development process is presented in the article by Gassaway (7). Here we describe how patient education and care management activities are subdivided into 10 educational and 3 care management topics, which are quantified in the supplemental nursing documentation.

Table 1.

Activities and Administrative Information Included in Nursing Point-of-Care Documentation

Patient and Caregiver Education

Patient and caregiver education is an integral component of every area of nursing intervention in the SCI rehabilitation setting. Education is provided in short informal sessions, longer organized one-on-one individual patient/caregiver education sessions, and broader group-oriented classroom activities. Group classes and other formal methods of patient and caregiver education are captured separately for the SCIRehab study. These formal methods of education are not the exclusive responsibility of nursing, and, in some centers, nursing is minimally involved; therefore, only the ongoing one-on-one education provided “bedside” by nurses is the focus for the nursing taxonomy.

In developing this classification, each SCIRehab center's patient education program and nursing documentation tools were reviewed for points of commonality and differences. A spreadsheet containing about 100 different education topics was created. The project nursing leaders determined which education topics were covered almost exclusively by nursing and not in group education formats and consolidated these into 10 main areas. The resulting education topic list is outlined in Table 1. The group postulated that more intensive nursing involvement in education would be associated with better rehabilitation outcomes but concurred that this intensity may be difficult to obtain from current medical record data. Thus, intensity (or dose) of patient and caregiver education is quantified using time. SCIRehab nursing documentation captures “blocks” of education time in 10-minute increments. Shorter periods of education are not added together to equal 10 minutes, because the focus is on capturing more significant education sessions.

Most of the education topics are routine SCI rehabilitation interventions (eg, medication, bowel, bladder, skin). However, 2 topics bear further explanation: complications and therapy carry over.

Patients may develop complications, which diminish or eliminate their ability to take advantage of therapeutic interventions and effectively progress through rehabilitation. Nurses often have to explain and provide education to patients and family members about such medical complications as autonomic dysreflexia, fevers, and infections. Therapy carry over is an integral part of nursing function in the rehabilitation setting. On a daily basis, nurses reinforce activities and/or topics that are taught initially by other disciplines: education on splint application, use of bowel management devices and equipment, transfer techniques, ADLs, feeding, etc.

Care Management

Care management, which includes discharge planning, psychosocial support, and team process, is a critical component of the role of SCI rehabilitation nurses, consumes a great deal of nursing time, and has the potential to have a significant impact on patient outcomes. The care management functions of SCI nurses are supplementary to the role of the case manager or social worker. Nurses undertake care management activities to communicate with other members of the rehabilitation team, the primary and consulting medical staff, the nursing team during shifts and at shift change, and patients and caregivers/families. These care management activities may include informal meetings and discussions about care planning but do not include team meetings, patient/family conferences, or other formal care/case planning meetings. These formal meetings/conferences are being collected in the social worker/case management point-of-care system.

Discharge Planning.

Nurses play a major role in preparing patients for discharge. This comprehensive process begins at admission to the rehabilitation center; includes educating home care providers, providing instructions for medications, and ordering supplies; and ends with the final discharge from the center. Completion of thorough and accurate discharge instructions is essential to the continuation of quality patient care after discharge from initial rehabilitation. The discharge planning process also includes an assessment of what information the patient or family member has retained for functioning in the community.

Psychosocial Support.

Spinal cord injury brings with it a plethora of psychological and social adjustments for patients and potential caregivers. Nurses, who are present throughout most of the patient's day, often spend a great deal of time listening to and coaching patients and families through challenging emotional times; they are the sounding board for real fears and dilemmas that develop. Psychosocial support entails the listening process and gleaning of information for referral to the appropriate professional; it does not include in-depth counseling, which may be undertaken by the psychologist, psychiatrist, rehabilitation counselor, social worker, or case manager.

Team Process.

All interactions between a nurse and other members of the interdisciplinary team (eg, physician report, collaboration with specialists, planning with therapists or nursing technicians) related to their common patients are included in team process care management. Intensity of team process, even informal hallway discussions, which frequently happen in SCI rehabilitation units, may influence patient outcomes. Team process, in this context, does not include team rounds or conferences, which is captured elsewhere by the SCIRehab team.

Patient Participation

Several studies suggest that an individual's degree of active participation in rehabilitation is related to level of improvement in function (8) and is crucial to other rehabilitation outcomes (9,10). Nurses work to inspire and enable patients to develop their capabilities to their highest potential, but if the patient is not motivated to participate, the outcome will be less than desired.

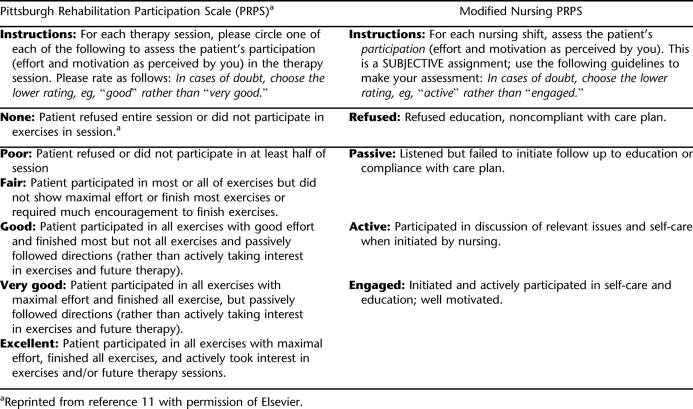

There are no published instruments currently available to measure patient participation in the full rehabilitation process or during the time spent within nursing care. However, Lenz et al developed the Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale to measure patient participation in physical therapy and occupational therapy sessions in an inpatient rehabilitation setting (11). The nursing group agreed, as did other disciplines in the SCIRehab project, that this scale offered a promising conceptual framework for measurement of patient participation activities throughout each nursing shift.

Concepts of participation that were found to differentiate patients in the Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale were retained but adapted and reworded to better reflect participation in nursing shift activities. The number of anchor points was reduced from 6 to 4 (for nursing), which provided less overlap among selection options. The clinician-rated measure rates the overall participation in care (including education activities) during the nursing shift. It is completed for each nursing shift, no matter the shift length. If the nurse is unable to rate participation because the patient is sleeping or off the unit for the entire shift, there is an option to document this. Table 2 compares the original Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale and the modified instrument utilized to measure participation in activities of the nursing shift.

Table 2.

Original and Modified Participation Scale

Implementation of the Collection of Taxonomic and Related Data

Capturing the Data.

Extensive nursing care data are contained within the medical record for every patient enrolled in the study and will be captured using medical chart abstracting. Methods used to capture supplemental nursing education and care process data vary among the 6 centers. Two centers were able to update current computerized documentation in a timely manner to integrate the SCIRehab nursing data set into existing electronic records and meet study implementation timelines for data collection. The additional information became part of the shift-by-shift computerized nursing documentation. Nurses at 4 centers, in which electronic nursing records do not yet exist or there was less flexibility to modify existing records, were required to use handheld personal digital assistants (PDAs), as do the other disciplines collecting SCIRehab data, to capture the supplemental nursing data.

Staff Education and Implementation.

Implementation of the supplemental nursing data capture methods required extensive staff education. A variety of methods were utilized for staff education; nursing leaders at each center were responsible for coordinating the education. Content of the nursing staff education was similar at each center. An introduction to the study purpose provided a description of nursing participation in the large, interdisciplinary, multicenter study. Emphasis was placed on the importance of accurate and timely nursing documentation. Details of documentation that would be extracted from the medical record were included so that nurses would understand the full scope of nursing information that would be included in the study. Quantifying patient education delivered, by topic and time, was new for nurses. The nurses needed to understand how to categorize time increments correctly. The minimum time increment to include in the documentation was 10 minutes. Although nursing staff routinely spend significant time on team process activities, documenting these efforts in time intervals was also new. Another major (and new) focus of staff education was the participation scale. Differentiating between the participation categories is sometimes difficult, and assigning a single participation value to a patient who varied his involvement and interests during a full nursing shift of 8 or 12 hours can be challenging.

Reliability of Documentation.

Reliability audits are completed to ensure consistency of documentation between the 6 centers and among individual nurses at each center. Case studies written by the project nurse leaders outline a hypothetical patient's care for a nursing shift. Each case study indicates what education and/or care management were delivered, to whom (patient and/or caregiver), and for how long, along with a description of the patient's participation in all activities. All nurses participating in the SCIRehab study at the 6 centers are asked to complete the reliability case studies. Achieving a high completion rate was the first challenge. The number of nurses working on the 6 study units ranges from 40 to 115. Although the clinical leaders who wrote case scenarios thought them to be clear and concise, it became apparent that the reading of narrative descriptions leads to varied interpretation by staff nurses. There are many changes within the course of a nursing shift, and, thus, although the case study was meant to be “black and white,” the context in which staff nurses complete their patient care is much more complex. Over time, good reliability was achieved by reinforcing the concepts, creating consensus on the meaning of the point-of-care categories, etc.

DISCUSSION

The intent of the SCIRehab study is to determine how variations in current nursing practice affect outcomes for patients receiving rehabilitation for a new SCI. Substantial documentation of general aspects of nursing care is available in medical records and will be examined. However, although nursing leaders in SCI deem patient education as one of the most important services that nursing contributes to patients with SCI, nurses do not document the intensity of education efforts. Typical documentation of education consists of checking boxes on a form listing SCI education topics to indicate that education has been done; by the time of discharge from rehabilitation, all boxes must be checked or discharge may be delayed. Time spent on education, delineation of areas of education completed, and the degree to which a patient participates in education are not documented consistently. Thus, to quantify this important contribution of nursing care, supplemental documentation was required at all 6 participating SCI centers. To make this change in traditional documentation practical, nursing leaders established a minimum interaction duration of 10 minutes to include, which would be considered “significant.” Not included were the brief interactions in which nurses pass through a patient's room or stop by a patient in the hall to discuss/educate about a certain topic for a few minutes or routine medication administration during which the nurse may mention the reason for a specific medication but not provide “significant” education. However, although this definition for “significant time” was intended to simplify documentation and minimize burden on the nurse, it also created concern, because nurses wanted to reflect the occurrence of these shorter interactions, especially if multiple small teaching moments occurred during a shift. For example, if a nurse discusses bladder management techniques for 3 to 5 minutes with the patient multiple times during a shift, is this not as influential and important as 1 10-minute session?

In the end, it was decided that only educational sessions lasting 10 or more minutes were significant and needed to be recorded. A major challenge was to ensure that requisite study documentation did not lead to practice modifications. Documenting patient and caregiver education in intervals was new, so nurses needed to be educated not to change education practices to fit the 10-minute parameter or to “get credit” for all of the minutes they spent on education vs capturing “significant” education only.

Learning to use supplemental documentation required extensive education at each center, regardless of the approach (electronic medical record supplement or PDA). Facilities that use PDAs introduced a process that was not familiar to many nurses, and for them the learning curve was steep. Efforts were needed to learn the new content, as well as the technical aspects of electronic documentation. Also, it is not common that nurses consistently document during the shift as interventions are completed; it is more typical for them to complete all documentation at the end of the shift. Recording accurate amounts of education duration required more frequent entry of data.

The 2 facilities that chose to incorporate supplemental documentation into their existing documentation systems (and not utilize PDAs) had to familiarize nurses with additional flow sheets or documentation forms/screens. Here, too, some nurses had difficulty adapting to recording data soon after interactions with patients occurred so that data were captured accurately.

Assigning one patient participation score to a patient's efforts during a full nursing shift can be challenging when patient participation can vary significantly in 8 or 12 hours of time. A patient may be very participatory in the morning but after therapy and meals may be too exhausted to continue at the same level. Some patients may be very engaged in particular aspects of their rehabilitation, such as going to therapy, but not interested in participating in other aspects, such as their bowel program. Nurses needed to be trained to “average” patient participation over the entire shift. In addition, nurses sometimes have difficulty matching the participation scale options to patient behaviors, even if the latter are consistent (eg, in “buy in,” interest) over a shift and over the various components of the rehabilitation process. It is fairly easy to determine if the patient refuses or is passive throughout the shift. However, differentiating between active and engaged is not as straightforward. The definition for active includes initiating discussion with prompting or encouragement and participating in self-care and/or education activities when these activities are initiated by nursing. Contrast this to engaged participation, which is defined as the patient's initiating and being motivated to engage in self-care and or education.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the requirement of completing supplemental documentation at the point of care, the impact on SCI nurses has been minimal. Most nurses agree that documenting details of important nursing contributions to the rehabilitation process should occur, because the intensity of education and care management may have significant associations with patient outcomes at the time of and after discharge from the rehabilitation center.

Each facility anticipates that the changes made to their documentation systems and processes for purposes of the study will, with minor modifications, be made permanent after completion of the study. Documenting education, care management, team process, and patient participation has added depth to nursing documentation that was missing prior to the study. This probably is the best indicator of the significance of the elements of SCI rehabilitation nursing selected for supplemental documentation in the SCIRehab project.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), Office of Special Education Services, US Department of Education to: Craig Hospital (grants H133A060103 and H133N060005), National Rehabilitation Hospital (grant H133N060028), Carolinas Rehabilitation (grant H133A21943–16), Shepherd Center (grant H133N060009), and Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (grant H133N060014).

This is the 8th in a series of 9 articles describing The SCIRehab Study Project: Classification of SCI Rehabilitation Treatments.

REFERENCES

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Outcomes following traumatic spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2000;23(4):289–316. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2000.11753539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellatt G. Perceptions of the nursing role in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Br J Nurs. 2003;12(5):292–299. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2003.12.5.11175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May L, Day R, Warren S. Evaluation of patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: knowledge, problem-solving and perceived importance. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(7):405–413. doi: 10.1080/09638280500192439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph S, Mailey S, Hayes K, Deneselya J, Kraft M, Bachand J. Validation of nursing sensitive outcomes in persons with spinal cord impairment. SCI Nurs. 2003;20(4):251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olinzock B. A model for assessing learning readiness for self-direction of care in individuals with spinal cord injuries: a qualitative study. SCI Nurs. 2004;21(2):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteneck G, Gassaway J, Dijkers M, Jha A. New approach to study the content and outcomes of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: The SCIRehab Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):251–259. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassaway J, Whiteneck G, Dijkers M. Clinical taxonomy development and application in spinal cord injury research: The SCIRehab Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):260–269. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder R, Granger C. Functional Evaluation of Stroke Patients. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1996. Functional independence measure: a measurement of disability and medical rehabilitation; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lenze E, Munin M, Dew M, et al. Adverse effects of depression and cognitive impairment on rehabilitation participation and recovery from hip fracture. Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(5):472–478. doi: 10.1002/gps.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Zimmerman S, Magaziner J, Adelman A. Use of the apathy evaluation scale as a measure of motivation in elderly people. Rehabil Nurs. 1998;23(3):141–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1998.tb01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze E, Munin M, Quear T, et al. The Pittsburgh rehabilitation participation scale: reliability and validity of a clinician-rated measure of participation in acute rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(3):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]