Abstract

Context:

The integration of psychologists as members of the rehabilitation team has occurred in conjunction with the evolution and adoption of interdisciplinary teams as the standard of care in spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation. Although the value of psychological services during rehabilitation is endorsed widely, specific interventions and their association with patient outcomes have not been examined adequately.

Objective:

To address this shortcoming, psychologists from 6 SCI centers collaborated to develop a psychology intervention taxonomy and documentation framework.

Methods:

Utilizing an interactive process, the lead psychologists from 6 centers compiled an inclusive list of patient characteristics assessed and interventions delivered in routine psychological practice at the participating rehabilitation facilities. These were systematically grouped, defined, and compared.

Results:

The resulting taxonomy became the basis of a documentation framework utilized by psychologists for the study. The psychology taxonomy includes 4 major clinical categories (assessment, psychotherapeutic interventions, psychoeducational interventions, and consultation) with 5 to 10 specific activities in each category.

Conclusions:

Examination of psychological interventions and their potential association with positive outcomes for persons who sustain SCI requires the development of a taxonomy. Results of these efforts illustrate similarities and differences in psychological practice among SCI centers and offer the opportunity to blend research and clinical practice in an innovative approach to evidence-based practice improvement. The established taxonomy provides a basic framework for future studies on the effect of psychological interventions.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries; Rehabilitation, physical; Psychology; Classification; Taxonomy; Practice-based evidence; Health services research

INTRODUCTION

Psychology services often are provided as part of an interdisciplinary team approach in inpatient rehabilitation settings. However, few studies have evaluated their effectiveness (1). Brown described the development of team care and noted trends related to this process within the field of rehabilitation (2). Before World War II, medical, nursing, and allied health specialties, which promoted coordination of rehabilitation care, were established. After the war, “comprehensive care” became the mechanism to address patients' physical, social, and vocational needs. During the 1960s, the team approach was institutionalized, which promoted greater equality among allied health professionals, but there was little discussion about the merits of the team approach (2). Only during subsequent years did investigators focus on team dynamics and effectiveness. In the last decade, research has identified multiple variables (eg, process variables, characteristics of team functioning) that affect the outcome of stroke and brain injury rehabilitation (3,4).

Faith in team approaches to rehabilitation care came under scrutiny as cost containment efforts intensified in the past 20 years. Keith examined origins of the team approach and its function and effectiveness (1,5). In his 1991 article, he reported a lack of research in specific areas of medical rehabilitation. Descriptive phrases, such as “comprehensive rehabilitation” and “inpatient rehabilitation,” to characterize treatment are common. However, most studies examine characteristics of patients, specifically their physical impairments, but not the specific amounts or types of treatments received. Keith encouraged research to improve “the understanding of what it is in the rehabilitation intervention that produces change in the patient's performance” in order to develop an effective and efficient system of rehabilitative treatment. He noted, however, that “Such research requires detailed observations, and is often tedious and expensive” (1).

These issues are particularly germane to the study of psychological interventions that are provided in spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation. It is not clear what interventions and activities, applied at various points during the course of rehabilitation, best serve patients' needs for effective and efficient rehabilitative treatment. Previous studies in the rehabilitation literature demonstrated positive functional outcomes with specific interventions delivered to patient populations other than SCI. Intensity (length of time in therapy) of psychological services related to functional gain in the cognitive realm (6) and providing injury-specific personalized information to persons with traumatic brain injury (7) related to positive functional gains in physical therapy, the effort patients exerted, and cognitive improvement. Pegg's study noted that providing such information gave patients a perspective of autonomy and control, which produced better health outcomes (7).

Despite these efforts, the term “black box” continues to be used to describe how almost all rehabilitation outcomes research has approached rehabilitation as an amalgam of undifferentiated and unspecified interventions provided as part of team rehabilitation. Gassaway and DeJong identify physical, occupational, and speech therapy treatment components associated with positive stroke rehabilitation outcomes (8,9); psychological treatments, however, were not examined.

The aim of this article is to describe a taxonomy of psychology interventions in SCI rehabilitation developed by a group of psychologists as part of the SCIRehab research project and to illustrate the potential use of this taxonomy in contemporary rehabilitation psychology practice and future research.

SCIREHAB PROJECT

The National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research funded a major national effort in 2006 to shed light on the “black box” of SCI rehabilitation. The SCIRehab Project is a 5-year investigation conducted at 6 SCI clinical treatment facilities, 5 of which are National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Model SCI System Centers. The SCIRehab study is designed to determine which SCI rehabilitation interventions are associated with positive outcomes at discharge and 1-year after injury. It assesses interventions used and the time spent in various rehabilitation therapies, as well as patient characteristics. Over 2.5 years, 1,500 consecutive initial acute rehabilitation patients with traumatic SCI consenting to participate will be enrolled at 6 centers. The first article in this series describes the SCIRehab study in greater detail and sets forth the crucial importance of center-to-center practice differences for the practice-based evidence methodology, which capitalizes on variations in treatments that are not related to patient needs or other patient characteristics (10).

Six senior psychologists, 1 from each of the SCIRehab sites, used 2 face-to-face meetings and weekly conference calls over 9 months to create a taxonomy of psychology interventions used in SCI inpatient rehabilitation and to create the larger treatment documentation framework into which it was embedded. Using an interactive process, these lead clinicians first compiled an inclusive list of patient characteristics that are typically assessed and interventions that are commonly delivered in routine psychological practice at the participating rehabilitation facilities. The latter were systematically grouped, defined, and compared. The resulting draft taxonomy was applied to case material and revised to make sure that all distinctions between interventions could be drawn in daily practice and were not too detailed to create a burden on clinicians.

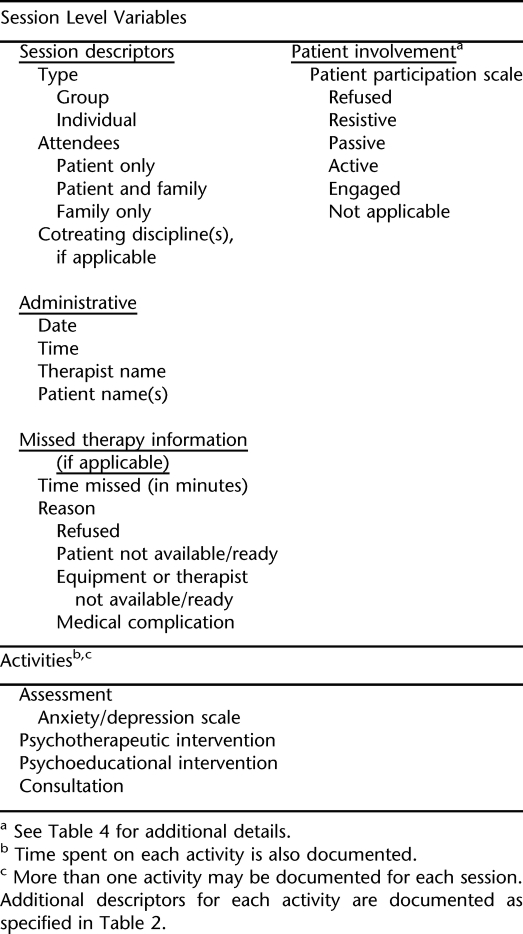

The overall psychology documentation (including taxonomic information) is consistent with the format used in other SCIRehab discipline documentation: general session information, topics (intervention activities) discussed in the session (taxonomy), and session-level variables, such as patient participation (Table 1). A description of the interactive development process is presented in the second article in this series (Gassaway et al) (11). Different from the other disciplines, however, the psychology documentation framework first identifies to whom the session interventions are aimed: patient only, patient and family, or family without patient. This reflects the importance psychologists place on helping the family, as well as the patient, understand the complex adjustment to a new lifestyle, as well as how the SCI affects all persons with whom the patient has relationships (10).

Table 1.

Activities and Session Variables Included in Psychology Point of Care Documentation

THE PSYCHOLOGY TAXONOMY

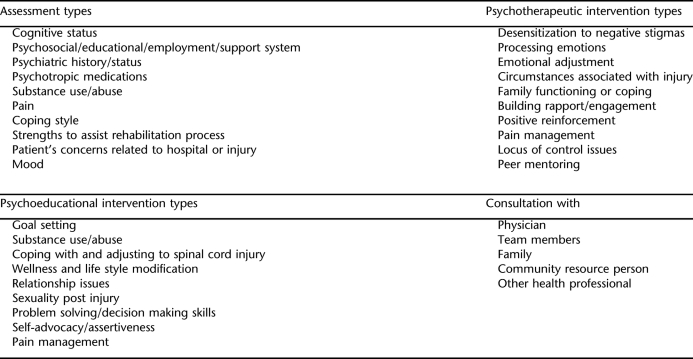

SCIRehab's lead clinical psychologists identified 4 major areas of therapeutic interaction with or for patients with SCI: assessment, psychotherapeutic interventions, psychoeducational interventions, and consultation (Table 2). Within each of the 4 areas, specific content details are distinguished, as detailed below. Several additional SCIRehab documentation variables used by the psychologists are comparable with those used by other disciplines, including amount of time spent on an intervention in a therapy session and missed therapy session time and reason; these are described in the article by Gassaway (11).

Table 2.

Psychology Activities

Assessment

Psychological assessment is conducted via clinical interview with the patient and family members, if available, along with chart review and direct observation. The assessment intervention activity in the psychology taxonomy includes 10 common assessment topics (Table 2). At most SCIRehab centers, a patient's cognitive status (arousal, attention, orientation, thought processes, and content) usually is assessed initially without using a standardized mental status tool. However, previous research suggests a 50% incidence of concussion and 20% of more severe tramatic brain injury in patients who experience SCI. Formal cognitive assessment is pursued when clinically indicated (12–14).

Psychosocial/Educational/Employment/Support Systems.

Psychosocial history includes gathering information regarding marital status, number of children or dependents, and living arrangements (eg, alone, with family, friends). Educational history includes the number of years of formal education attained, any degrees earned, and a determination of whether past learning problems could interfere with new learning and carryover. Preinjury employment status relates to whether the patient is working, retired, volunteering, unemployed, or disabled from employment; highlights of the person's educational and employment history may also be reviewed. The presence or absence of a network of supportive others available to nurture the patient emotionally and promote active participation in rehabilitation is evaluated, along with spiritual support systems.

Any pre-existing psychiatric history/status, including diagnoses and treatment, is relevant to assess along with a review of the medical record for current psychotropic medications. Another variable to be screened is current or prior substance use/abuse, including alcohol and recreational drugs. Pain management techniques and education often are among the psychological interventions provided in SCI rehabilitation, and, thus, it is relevant to assess the patient's pain (pain scale score, where the pain is localized, and whether current pain management strategies effectively control the pain).

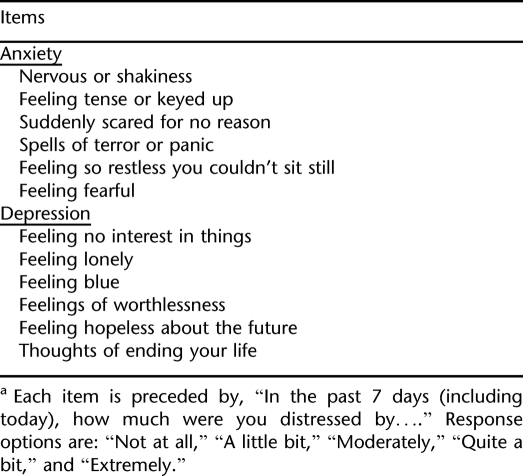

Coping style relates to how an individual handled stressors prior to injury. Assessment of personal strengths to assist the rehabilitation process (eg, assertiveness, determination, optimism, strong work ethic) can illuminate premorbid personality and behavior patterns and, thus, aid in treatment planning. Patient concerns related to the hospital stay or injury are reviewed to determine areas of particular relevance to the patient that the psychologist will address in therapy sessions. Mood is assessed both clinically and by patient self-report via a modified version of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Anxiety/Depression Scalea

Psychotherapeutic Interventions

Because inpatient rehabilitation is a time-limited process, with average lengths of stay ranging from 28 days for individuals with incomplete paraplegia to 50 days for individuals with complete tetraplegia (15), psychotherapeutic interventions must be geared toward the most immediate goal of helping patients and families cope with what has happened to them physically, assessing how they feel about their functional losses and other resulting life changes, and facilitating preparation for life outside of the rehabilitation setting.

Psychotherapeutic intervention can be conceptualized as encouraging a patient to connect with threatening emotions while not pushing beyond the patient's level of tolerance and, thus, risking psychological withdrawal. General themes of psychotherapeutic intervention often include examination of expectation, fostering a sense of mastery and self advocacy, accepting healthy support, mourning loss, and reframing conclusions/decisions about one's problems (16).

The psychology taxonomy includes 10 psychotherapeutic interventions used with patients and their families during SCI rehabilitation (Table 2).

Desensitization to negative stigmas helps the patient deal with feelings related to being different, either in appearance or in manner of doing things, such as using a wheelchair for mobility or assistive devices for eating, grooming, writing, etc. Similarly, desensitization focuses on addressing feelings related to the anticipation or actual encountering of lack of understanding/education in the community about SCI and its ramifications.

Processing emotions is aimed at the grieving process and involves validation and normalization of the patient's feelings of anger, sadness, anxiety, depression, etc. Processing emotions is differentiated from emotional adjustment, which includes discussions about how adjustment to the disability and/or use of coping strategies is progressing.

Circumstances associated with injury facilitate the patient's identification and understanding of lifestyle factors, such as intoxication and risk taking, that may have contributed to the injury. This intervention also includes helping the patient manage feelings, such as anger and guilt, that relate to the nature/cause of the SCI, which could affect progress during rehabilitation and postrehabilitation adjustment.

The psychotherapeutic intervention of family functioning or coping identifies and addresses issues related to grief and loss affecting the patient and significant others, as well as their coping with the rehabilitation experience and preparation for life after discharge from the rehabilitation setting. The goal is to increase insight and/or awareness of feelings and issues that may hinder or facilitate healthy grieving and adaptation.

Building rapport/engagement is a part of all psychotherapeutic activities. However, a separate intervention to encompass rapport building and therapeutic engagement is included in the psychology taxonomy to describe interactions with a patient that occur specifically for the purpose of developing the therapeutic relationship, getting to know the patient better, or putting the patient more at ease so that meaningful psychotherapeutic intervention can occur in future meetings.

Therapists use positive reinforcement to encourage healthy and adaptive coping skills, effective problem solving, and sound decision-making skills to increase opportunities for success in rehabilitation and after discharge.

Pain management is addressed psychotherapeutically when the psychologist helps the patient to address emotional aspects of pain, such as anxiety, which can interfere with effective coping and management of pain. Pain management strategies that are addressed didactically or in lecture or class format are recorded elsewhere as psychoeducational interventions.

When the psychotherapeutic intervention targets locus of control issues, the session addresses feelings that relate to a perceived lack of ability to affect one's environment, schedule, goals, or discharge decisions. The goal of this intervention is to help the patient feel an increased sense of control in decisions about rehabilitation and life after rehabilitation.

Peer mentoring is documented when the psychologist facilitates discussion of feelings, experiences, or coping strategies between a patient and another person who sustained a SCI.

Psychoeducational Interventions

In addition to psychotherapeutic interventions, psychologists provide interventions that are more educational in nature. These psychoeducational interventions can be delivered in an individual or group format and may include family members as recipients of the information. The key goals of these interventions are to help patients learn and understand common physical and emotional changes associated with SCI and to teach patients problem-solving strategies for life outside of the rehabilitation setting. Previous research has demonstrated that psychoeducational interventions can facilitate increased compliance with rehabilitation therapies, as well as overall health and functional outcomes (7). The psychology taxonomy includes 9 psychoeducational interventions that capture the most common didactic interventions used with patients and their families during SCI rehabilitation (Table 2).

In providing education on goal setting, the psychologist supplies information on how the SCI rehabilitation process is driven by setting goals that help patients overcome specific problems caused by SCI. The psychologist may extend this approach to educating patients on how setting logical goals for oneself can lead to a greater level of life fulfillment.

Substance use and abuse education might emphasize the increased susceptibility to substance abuse by persons with SCI and the heightened adverse effects substance use (including pain medications) can have on a person after SCI. These discussions can lead to education on prevention and treatment options for persons with substance abuse concerns.

In the area of coping with and adjusting to SCI, the psychologist educates the patient and/or the family on the normal processes and phases associated with adapting emotionally and socially to having a disability. As with substance abuse concerns, this opens the door for education on treatment options for persons who are having difficulty with the emotional and social challenges associated with SCI.

The psychologist provides wellness and life style modification information so that behaviors known to promote health stability can be incorporated into one's life. These may include making healthy dietary changes, exercising consistently, and avoiding high-risk behaviors. Suggestions also may be given on other sources for information on health promotion, including referrals to other professionals, such as dieticians, recreational therapists, psychologists, and physicians.

Relationship issues are addressed by the psychologist to highlight specific ways that relationships with other persons, including family members, friends, strangers, and coworkers, are affected by SCI. In addition, the therapist is likely to instruct the patient on effective ways to enhance these relationships. Discussion of relationship issues often leads to addressing sexuality post injury, where information is provided on specific physical, social, and psychological effects of SCI on sexual functioning (including fertility) and effective ways of engaging in healthy sexual interactions.

Problem solving/decision-making skills education emphasizes the importance of utilizing cognitive abilities in rational planning and execution to overcome life challenges, particularly those resulting from SCI. This is important during the inpatient stay and also helps patients to generalize acquired skills to their daily lives outside of the rehabilitation setting.

Self-advocacy and assertiveness interventions teach the value and importance of advocating for one's care and social opportunities and utilizing assertiveness skills that balance respect for self and others as the patient strives to get the services to which they are entitled. This can be taught in the context of medical needs and the individual's quest for positive social reintegration after SCI. Also, education can target partnering with other members of the disability community who advocate for fair treatment by society.

Pain management education focuses on teaching the patient about the physical and psychological aspects of pain after SCI, as well as teaching her/him psychological strategies that complement medical interventions for SCI-related pain. This is the only topic that is included as both a psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational intervention in the SCIRehab taxonomy, and, indeed, it is possible to include education and therapy about pain management within the course of the same session.

Psychologist as Consultant

Upon admission, the psychologist assesses the patient to facilitate transition to the rehabilitation environment and to aid the team's understanding of the patient's personality, affective functioning, and behavioral responses. The psychologist addresses nonproductive interactions between the team and the patient, between the team and the family, or between team members. Gans' article, “Hate in the Rehabilitation Setting,” identifies the overlooked clinical issue involving the expression of intense negative reactions by the patient, family, or staff. The psychologist educates the team and family on how these strong reactions can be manifested in the rehabilitation setting (17). A recent survey of rehabilitation team members documents the difficulty of these negative reactions (18). Team members rate family expectations significantly more difficult to address than treatment goals, length of stay, discharge planning, and prognosis. The psychologist often is called upon to facilitate the difficult challenge in helping the treatment team balance the family's hope with the anticipated functional outcome (18).

To capture accurately the time spent in consultation, 5 categories are included in the psychology taxonomy (Table 2): consultation with physicians, other team members, family, community resource person(s), and other health professionals. Consultation must be at least 10 minutes in duration to be recorded. The psychologist aids staff in empathizing with the patient through promoting mutual understanding and normalizing patients' emotional reactions. The process helps both staff and patient to set no punitive boundaries. Consultation with members of the rehabilitation team, patient, and family often include the following steps: (a) clarify the situation, (b) normalize the behavior, (c) explore conflict and emotions, (d) provide information in concrete and common terms instead of technical or professional language, and (e) educate the staff regarding the patient's reactions.

In the rehabilitation setting, observations, impressions, and recommendations are shared during team conferences, common goals are established, and a comprehensive treatment plan is prepared. Consultation by the rehabilitation psychologist addresses and facilitates communication among the interdisciplinary team members. The psychologist acts as a liaison between team members when there is a difference in terminologies or an overlap in roles, thereby maximizing cooperation and unification of the team. Consulting with team members can be an indirect form of treating the patient and is one that often is underappreciated in the overall evaluation of the rehabilitative process.

SUPPLEMENTAL ELEMENTS

Anxiety/Depression Scale

Understanding a patient's affective status helps to determine the need for and extent of ongoing psychological treatment, education, and consultation with team members. At the 6 SCIRehab centers, it was not routine practice to use any specific tool other than a clinical interview to evaluate affective status at the onset of rehabilitation. Elliott and Frank emphasized the lack of standardized measurement as a fundamental problem in advancing research of affective disorders in the SCI population (19). Previous research estimates the incidence of depression and/or anxiety in inpatient SCI rehabilitation at 20% to 43% (20). Depressive symptoms and anxiety after discharge have been estimated to range from 15% (21) to 50% to 60% (22,23). Individuals with higher levels of distress have higher perceptions of pain, poor sleep, feelings of helplessness, and increased medical complications during rehabilitation (19). Thus, the SCIRehab lead clinical psychologists determined that it would be appropriate and necessary to capture affective symptoms in a semistandardized way for each study patient.

Several published instruments were considered, including the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, which has been used to identify depressive symptoms in the SCI population (24). However, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 does not screen for anxiety; symptoms of anxiety often are prevalent in individuals with new SCI and, thus, are important to assess at the outset of rehabilitation.

The BSI authored by Derogatis is a self-report symptom inventory using a 5-point rating scale to capture anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms. It is quick and easy to complete, requiring only a sixth grade reading level for completion, and it has equivalent English and Spanish forms (25).

The SCIRehab Project team accepted the 6 anxiety and 6 depression BSI items but opted not to use the 6 somatic items, because somatic symptoms in the SCI population may be endorsed due to the physical effects of the injury rather than being a reflection of the patient's emotional status (Table 3). Permission to use an abbreviated version of the BSI was obtained. The scale is administered within the first 2 weeks of rehabilitation or during one of the first 3 encounters with the patient, whichever comes first. Each patient is given a paper copy of the BSI to mark responses for the 12 items. If a patient is not able to do so, the examiner reads each question or shows the paper copy to the patient and marks the chosen responses. If the psychologist considers administration of the BSI to be clinically inappropriate due to the emotional or cognitive status of the patient, the clinician may exercise discretion and opt not to administer the scale or to delay administration.

Motivation/Participation

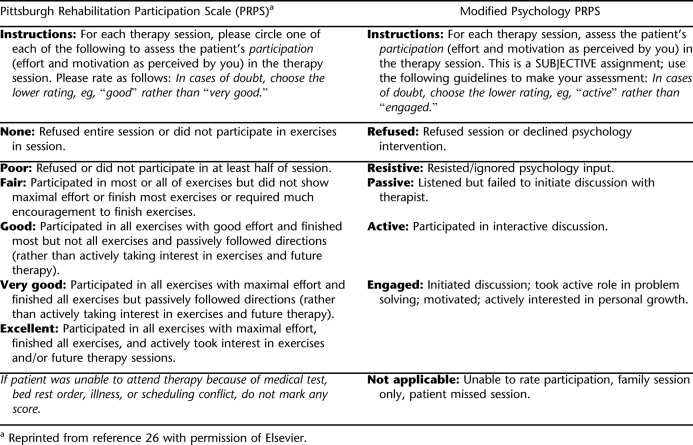

The second article in this series by Gassaway et al describes the importance of patient participation as a likely determinant of rehabilitation outcomes, as well as the adaptation of a measure of this construct (11). The Pittsburgh Rehabilitation Participation Scale (PRPS) was developed to measure patient participation in physical therapy and occupational therapy sessions in an inpatient rehabilitation setting. The measure was shown to be a reliable measure of patient participation in a sample of primarily elderly rehabilitation inpatients with a variety of diagnoses and was predictive of rehabilitation outcome as measured by functional independence measure score change (26). Although this scale was designed for use by physical therapy and occupational therapy, it is a promising conceptual framework for participation in psychological treatment delivered during inpatient rehabilitation. The SCIRehab psychologists developed a modified version of the PRPS in this study. Concepts of participation that differentiated patients during the refinement of the PRPS were retained but adapted and reworded to reflect the vocabulary of participation in psychological treatment. Table 4 compares the PRPS and the modified instrument to measure participation in psychological treatment sessions.

Table 4.

Original and Modified Participation Scale

DISCUSSION

Evidence-based practice has gained popularity in recent years in many fields of health care delivery, including psychological practice. However, this focus has served to illuminate longstanding conflicts and shared skepticism between researchers and practitioners. Those involved primarily in direct clinical service delivery have questioned the applicability and generalizability of the findings of psychotherapy research. Clinicians often wonder whether findings from carefully controlled interventional research can be used successfully in the “real-world” treatment of patients. Similarly, researchers question the rigor of psychological treatment guidelines and practices that arise primarily from the clinical experience of treatment providers. Although differences of opinion exist, Kazdin states that both research and practice are united “in their commitment to providing the best psychological knowledge and methods to improve quality care” (27). Kazdin further stresses the importance of direct collaboration between research and practice as a means to develop and strengthen our knowledge base. The SCIRehab Project presents a unique and innovative opportunity for such collaboration between clinical practice and research. It is hoped that through rigorous documentation of clinical practices utilized during inpatient rehabilitation after SCI, the identification of interventions most strongly associated with positive outcomes for persons who sustain SCI ultimately will result in a dynamic feedback loop for evidence-based practice improvement.

A key component of rehabilitation theory and practice for more than 50 years has been a team approach involving professionals, individuals with disabilities, and their families and communities working together to improve adjustment, increase function, develop adaptive techniques, reduce social stigma, increase social integration and participation, and advocate for disability rights and consumer participation. A critical aspect of an interdisciplinary approach to rehabilitation lies in the communication of multidimensional observations and impressions followed by the collaborative preparation of comprehensive goals and treatment plans. Rohe notes that within this rich interdisciplinary collaboration, the rehabilitation psychologist's overall aim is to enhance the quality of the rehabilitation outcomes for patients, including the patient's psychological and social adjustment to disability (28). Rehabilitation psychologists seek to achieve this aim through direct treatment of the patient and his or her family but also through facilitation of communication between patients and the interdisciplinary team to align expectations, build consensus, and maximize the collaborative achievement of successful treatment outcomes.

During development of the SCIRehab taxonomy of psychological interventions utilized in SCI inpatient rehabilitation, the primary and secondary classifications emerged through a collaborative analysis of the psychologists' roles in their respective settings. Direct interventions were classified as psychotherapeutic, psychoeducational, or consultative in nature. Although the distinction between psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions was not always clear, this distinction served as an important guidepost for describing the primary intent of a given clinical intervention. If the intervention was primarily intended to provide an emotionally supportive or healing experience, it was classified as psychotherapeutic. If the psychologist's primary intent was to convey information, the intervention was classified as psychoeducational, with the understanding that didactic interactions with patients also can facilitate a form of healing rooted in empowerment and knowledge acquisition.

Specific subtypes of interventions were identified to better describe the actual content of each session. Each subtype was defined as uniquely belonging to either psychotherapeutic or psychoeducational interventions, with the exception of pain management. Although it was acknowledged that substance abuse interventions could be construed as falling within either intervention area, it was agreed that interventions in this realm were usually primarily psychoeducational. In cases in which substance abuse interventions occurred in the context of psychotherapeutic intervention, clinicians were advised to document the psychotherapeutic intervention type that overlapped with substance abuse education. For example, if the patient expresses such feelings as guilt about substance abuse behaviors, the psychologist documents processing emotions in the psychotherapeutic category

The modified PRPS is a reasonable approach to the measurement of patient participation, as judged by the clinician, during psychological interventions in the inpatient SCI rehabilitation setting. However, there is a rich literature in the area of therapeutic alliance, which appropriately describes alliance and rapport between therapist and patient as bidirectional. In other words, patient participation must be understood in the context of patient and therapist factors that interact in complex ways to facilitate or complicate attainment of therapeutic goals (29–31). Given this well-established principle of the psychotherapeutic process, efforts were made to include in the SCIRehab study a mechanism for the measurement of patients' perception of therapeutic alliance during inpatient rehabilitation after SCI. Due to study limitations on patient interviews during rehabilitation, this mechanism was incorporated into the 6-month postinjury interview with the patient.

Fenton et al noted that the most commonly used measures of the therapeutic alliance across a variety of psychotherapy treatment modalities tap into several common core aspects of the alliance construct (32). These core aspects are described as client-therapist agreement on the goals of treatment, concurrence on the strategies to achieve these goals, and the quality of the shared affective bond. The focus on goal setting and attainment is one of the guiding principles of SCI rehabilitation, and alliance measures that tap these factors were thus felt to represent a promising means of assessing alliance in a rehabilitation setting from the perspective of the patient. The wording and conceptual framework of a short form of the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (33) was determined to meet the needs of the current study most closely.

Although the concept of therapeutic alliance may be of particular interest to psychologists, its importance and impact is not specific only to the delivery of psychological treatment in rehabilitation settings. Indeed, collaborative and respectful relationships between persons with SCI and the various members of the SCI rehabilitation team have been described as essential. Hammell published a metasynthesis of qualitative research describing patients' experience of rehabilitation after SCI and concluded, “… if financial resources were allocated according to the priorities of rehabilitation clients, these would be targeted, not at buildings, facilities or equipment, but at the recruitment and retention of a substantial number of caring, client-orientated staff” (34). Based on the concept that alliance with patients is an important factor not only for psychologists but also across disciplines within the SCI rehabilitation setting, it was recommended by the psychology clinical leaders that patients' perspectives on this construct be assessed across the various disciplines in the current study. To achieve this goal, 3 questions from the short form of the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale were modified slightly and added to the 6-month postinjury interview to be administered to all participants in the current study. Patients are asked to respond to each of the 3 questions using a 10-point scale (0 = not at all to 10 = very much). The questions assess the patient's perception of feeling sincerely understood, agreement between patient and clinician goals, and the nature of collaboration experienced. Each question is repeated for the various members of the rehabilitation team, including the physical therapist, occupational therapist, recreational therapist, speech and language pathologist, nurses, social worker or case manager, psychologist, and physician.

CONCLUSIONS

The development of the SCIRehab psychology taxonomy provides a foundation to understand the various aspects of therapist/patient interactions and to associate psychology interventions with outcomes for persons who sustain SCI. The collaborative efforts to develop this taxonomy provided the opportunity to blend research and clinical practice in an innovative approach to evidence-based practice improvement.

Footnotes

The contents of this article were developed under grants from the Department of Education, NIDRR grant numbers H133A060103 and H133N060005 to Craig Hospital, H133N060028 to National Rehabilitation Hospital, H133A21943–16 to Carolinas Rehabilitation, H133N060009 to Shepherd Center, H133N060027 to Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and H133N060014 to Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

This is the 7th in a series of 9 articles describing The SCIRehab Project: Classification of SCI Rehabilitation Treatments.

REFERENCES

- Keith R. The comprehensive treatment team in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72(5):269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Responsibility in health care. In: Agich G, editor; Brown T, editor. A Historical View of Health Care Teams. Dordrecht, Holland: Reidel; 1982; [Google Scholar]

- Strasser D, Falconer J. Rehabilitation team process. Top Stroke Rehabil. 1997;4(2):34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser D, Falconer J, Stevens A, et al. Team training and stroke rehabilitation outcomes: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith MS, Stanislav SW, Wesnes KA. Validity of a cognitive computerized assessment system in brain-injured patients. Brain Inj. 1998;12(12):1037–1043. doi: 10.1080/026990598121945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann A, Hamilton B, Linacre J, Wright B, Granger C. Functional status and therapeutic intensity during inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;74(4):315–326. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg PO, Auerbach SM, Seel RT, Buenever LF, Kiesler DJ, Plybon LE. The impact of patient centered information on patients' treatment satisfaction and outcomes in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Rehabil Psychol. 2005;50(4):366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Gassaway J, Horn S, DeJong G, Smout R, Clark C, James R. Applying the clinical practice improvement approach to stroke rehabilitation: methods used and baseline results. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(12 suppl 2):S16–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong G, Horn S, Conroy B, Nichols D, Healton E. Opening the black box of poststroke rehabilitation: stroke rehabilitation patients, processes, and outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(12 Suppl 2):S1–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteneck G, Gassaway J, Dijkers M, Jha A. New approach to study the content and outcomes of spinal cord injury rehabilitation: The SCIRehab Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):251–259. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassaway J, Whiteneck G, Dijkers M. Clinical taxonomy development and application in spinal cord injury research: The SCIRehab Project. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(3):260–269. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11760780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff G, Roth E, Richards J. Cognitive deficits in spinal cord injury: epidemiology and outcome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73(3):275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J, Brown L, Hagglund K, Bau G, Reeder K. Spinal cord injury and concomitant traumatic brain injury: results of a longitudinal investigation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;67:211–216. doi: 10.1097/00002060-198810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J, Kewman D, Pierce C. Spinal cord injury. In: Frank R, Elliott T, editors. Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychology Association; 2000. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Annual Statistical Report. Birmingham, AL: University of Alabama; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman D, Zimberoff D. Corrective emotional experience in the therapeutic process. J Heart Centered Ther. 2004;7(2):3–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gans J. Hate in the rehabilitation setting. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64(4):176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef J, Toussaint P, Putter H, Zwetsloot-Schonk J, Vliet Vlieland T. The impact of introducing an ICF based rehabilitation tool on staff satisfaction with multidisciplinary team care in rheumatology: an exploratory study. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(1):23–37. doi: 10.1177/0269215507079845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Frank R. Depression following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(8):816–823. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank R, Kashani J, Wonderlich S, Lising A, Visot L. Depression and adrenal function in spinal cord injury. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(2):252–253. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombardier C, Richards J, Krause J, Tulsky D, Tate D. Symptoms of major depression in people with spinal cord injury: implications for screening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(11):1749–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.07.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A, Hancock K, Dickson H. Spinal cord injury: a search for determinants of depression two years after the event. Br J Clin Psychol. 1994;33(2):221–231. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1994.tb01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P, Rogers B. Anxiety and depression after spinal cord injury: a longitudinal analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(7):932–937. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.5580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L, editor. BSI-18: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lenze E, Munin M, Quear T, et al. The Pittsburgh rehabilitation participation scale: reliability and validity of a clinician-rated measure of participation in acute rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(3):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A. Evidence based treatment and practice: new opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base and improve patient care. Am Psychol. 2008;63(3):146–156. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohe D. Psychological aspects of rehabilitation. In: DeLisa J, Gans B, editors. Rehabilitation Medicine: Principles and Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger M, Humle F, Teasdale T. The development of the therapeutic working alliance, patients' awareness, and their compliance during the process of brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2006;20(4):445–454. doi: 10.1080/02699050600664772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger M, Humle F, Teasdale T. Subjective outcome of brain injury rehabilitation in relation to the therapeutic working alliance, client compliance, and awareness. Brain Inj. 2006;20(12):1271–1282. doi: 10.1080/02699050601049395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger M, Humle F, Zeeman P, Teasdale T. Working alliance and patient compliance in brain injury rehabilitation and their relation to psychosocial outcome. Neuropsych Rehabil. 2006;16(3):298–314. doi: 10.1080/09602010500176476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton L, Cecero J, Nich C, Frankforter T, Carroll K. Perspective is everything, the predictive validity of six working alliance instruments. J Psychother Pract Res. 2001;10(4):262–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston L, Marmar CR. California psychotherapy alliance scales. In: Horvath AO, Greenberg LS, editors. The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hammell K. Experience of rehabilitation following spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(4):260–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]