Summary

Arsenic and selenium are metalloids found in the environment. Arsenic is considered to pose the most significant potential threat to human health based on frequency of occurrence, toxicity and human exposure. Selenium, on the other hand, ranks only 147th in toxicity but, in contrast to arsenic, is also a required micronutrient. Whether a toxin or micronutrient, their metabolism requires that cells to accumulate these metalloids. In this review we discuss the membrane proteins that transport arsenic and selenium into cells, from bacteria to humans, as well as some the efflux proteins involved in detoxification.

Introduction

Arsenic is one of the most common poisons found in the environment, introduced from both geochemical and anthropogenic sources, and is acted on biologically, creating an arsenic biogeocycle (Fig. 1) (4). The environmental prevalence of arsenic presents a health hazard in human populations world-wide. For example, arsenic in the water supply in Bangladesh and West Bengal is considered to be a health catastrophe (http://bicn.com/acic/infobank/bgsmmi/risumm.htm). Because of its ubiquity, toxicity and exposure to humans, arsenic ranks first on the Superfund List of Hazardous Substances <http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/cercla/05list.html>. Exposure to arsenic is associated with cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease, neurological disorders, diabetes mellitus and various forms of cancer (1, 2). Anthropogenic sources of arsenic include herbicides and pesticides, wood preservatives, animal feeds and semiconductors. Some contain inorganic arsenic such as chromated copper arsenate (CCA), which has been used for many decades to treat wood against attack by fungi and insects. If the wood is not sealed, the arsenic can find its way into human water and food supply. Both inorganic and organic arsenicals are used for agriculture and animal husbandry. During the last century, arsenic acid (H3AsO4), sold as Desiccant L-10 by Atochem/Elf Aquitaine, was euphemistically called “harvest aid for cotton” because it was used to defoliate cotton to allow planting of the next cotton crop. While it is no longer used agriculturally, the inorganic arsenic remains in fields throughout the southern United States. That land is now used for planting rice, and grocery store rice from those states constitutes the largest non-seafood source of arsenic in the American diet (45). The sodium and calcium salts of monomethylarsenate (MMA) and dimethylarsenate (DMA) are currently widely used as herbicides and pesticides. For example, the active ingredient in Weed-B-Gone Crabgrass Killer is calcium MMA. DMA and MMA are also widely used as a fungicide on golf courses in Florida, and the resulting arsenic enters the water supply of Florida municipalities. DMA, also known as cacodylic acid, is also used as a defoliant of cotton fields. Organic arsenicals such as Roxarsone (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylarsonic acid) are also used as growth enhancers and feed supplements in animal husbandry.

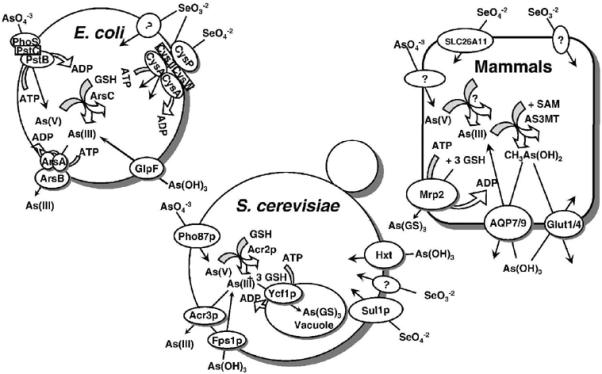

Fig. 1. Pathways of arsenic and selenium uptake and efflux in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Arsenate (As(V)) is taken up by phosphate transporters, while As(III) is taken up by aquaglyceroporins (GlpF in E. coli, Fps1p in yeast, and AQP7 and AQP9 in mammals), and hexose permeases (HXT1, HXT3, HXT4, HXT5, HXT7, or HXT9 in yeast, and GLUT1 and GLUT4 in mammals). In both E. coli and S. cerevisiae, arsenate is reduced to arsenite by the bacterial ArsC or yeast Acr2p enzymes. In both organisms, glutathione and glutaredoxin serve as the source of reducing potential. The proteins responsible for arsenate uptake and reduction in mammals have not yet been identified. In E. coli, arsenite is extruded from the cells by ArsB alone or by the ArsAB ATPase. In yeast Acr3p is a plasma membrane arsenite efflux protein, and Ycf1p, which is a member of the MRP family of the ABC superfamily of drug-resistance pumps, transports As(GS)3 into the vacuole. In mammals, Mrp isoforms such as Mrp2, pump As(GS)3 out of cells. Selenate is taken up by sulfate permeases, the CysAWTP ABC ATPase in bacteria, Sul1p in yeast and SLC26A11 in humans. By-and-large, the uptake pathways for selenite have not been identified.

As a consequence of its pervasiveness, nearly every organism, from E. coli to humans, has mechanisms for arsenic detoxification, most of which involve transport systems that catalyze extrusion from the cytosol (4). In bacteria, the genes for arsenic detoxification are usually encoded by arsenic resistance (ars) operons. Many ars operons have only three genes, arsRBC, where ArsR is an As(III)-responsive transcriptional repressor (49), ArsB is a As(OH)3/H+ antiporter that extrudes As(III), conferring resistance (26), and ArsC is an arsenate reductase that converts As(V) to As(III), the substrate of ArsB, hence extending the range of resistance to include As(V) (28). Some ars operons have two additional genes, arsD and arsA, such as the arsRDABC operon in E. coli plasmid R773. In these cells ArsA forms a complex with ArsB that catalyzes ATP-driven As(III)/Sb(III) efflux and hence are more resistant to As(V) and As(III) than those without ArsA (12). ArsD is an arsenic metallochaperone that transfers As(III) to ArsA, increasing its ability to extrude arsenite (22). Arsenicals and antimonials are also used as chemotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of parasitic diseases and cancer, and resistance to these drugs is commonplace. Thus, knowledge of the pathways, enzymes and transporters for metalloid uptake and detoxification is necessary for understanding their toxicity, for rational design of metallodrugs and for treating drug-resistant microorganisms and tumor cells.

Selenium is an environmental pollutant and ranks 147th on the Superfund Priority List of Hazardous Substances of the U.S. Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) (http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/cercla/05list.html). The maximum allowable concentration (MCL) of selenium by the World Health Organization (WHO) in drinking water is 10 ppb (approximately 10-7 M) (http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp92.html). Selenium has chemical properties similar to those of arsenic such a valence shells, electronic structures and atomic radii. Selenium enters the environment from both geochemical and anthropogenic sources. Much of selenium in the environment comes from selenium dioxide produced by burning of coal and other fossil fuels. Inhalation of selenide and selenium dioxide can produce serious injury to the respiratory tract, the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular systems, brain, muscle, kidney and liver (http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp92.pdf). The soluble forms of selenium are selenite (Se(IV)) and selenate (Se(VI)), which are more mobile and more toxic than elemental selenium.

While toxic at high concentrations, selenium is a required micronutrient, with a recommended dietary allowance of approximately 0.9 μg/kg of body weight, depending on age and sex. In China acute selenium deficiency results in Keshan Disease, which is characterized by an enlarged heart and impaired cardiac function (21, 25). Dietary supplementation with selenium alleviates Keshan Disease (7). Selenium is also required for production of thyroid hormone, and deficiency affects thyroid function (3, 19). Selenium deficiency has also been linked to neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, as well as to an increased risk of cancer (50) (6, 11) (9). At least 25 selenoproteins in which selenocysteine substitutes for cysteine, have been identified (40). These are mainly antioxidant enzymes such as peroxidases and oxyreductases that protect from oxidative stress. For example, human erythrocytes have a selenocycteine-containing glutathione peroxidase (GPx) that catalyzes glutathione-coupled reduction of and protection from hydroxyperoxides (36, 43). Clinical trials showed that selenium may also protect from prostate cancer (10, 13, 30, 34).

Selenium also protects against the toxic effects of toxic metal and organic compounds, including lead, cadmium, arsenic, mercury, and paraquat (18, 29, 44). Antagonistic effects or mutual detoxification between As and Se have been reported in humans and other animals (20, 27, 38, 51). What is the physical basis for their interactions? Selenium and arsenic probably interact during their cellular metabolism, including uptake, reduction, methylation, conjugation with glutathione (GSH) and excretion, as discussed below.

Pathways of uptake of As(V) and As(III)

Arsenic is a toxic element with no known nutritional or metabolic roles. Since cells would have no reason to evolve uptake systems for toxic elements, both trivalent arsenite and pentavalent arsenate are taken up adventitiously by existing transport systems (Fig. 1). Arsenate is a phosphate analogue and is take up arsenate by phosphate transporters in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In E. coli, both phosphate transporters, Pit and Pst, take up arsenate (35), with the Pit system being the major system (46, 47). Similarly, in yeast, phosphate transporters take up arsenate (31).

As a solid, arsenite in the form of As2O3, arsenic trioxide, dissolves to form As(OH)3 at physiological pH (33). We have identified two families of transport proteins for uptake of As(OH)3 in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The first family are the aquaporins, or more specifically, the aquaglyceroporin branch of that superfamily. We first identified the glycerol facilitator, GlpF, as the uptake system for As(III) (and Sb(III)) E. coli (26, 37). Uptake of arsenite by GlpF homologues renders bacteria sensitive to arsenite. In S. cerevisiae, Fps1p, the yeast homologue of GlpF, also allows for uptake of and sensitivity to arsenite (48). Leishmania major, a human pathogen, also takes up arsenite and antimonite by an aquaglyceroporin, LmAQP1 (17). Antimonite is the active form of the antileishmanial drug Pentostam, a pentavalent antimonial.

Recently we have shown that the Hxt glucose transporter permease family of S. cerevisiae adventitiously facilitate arsenite uptake in yeast (23). A number of the eighteen S. cerevisiae hexose transporters (Hxt1p to Hxt17p, Gal2p, and two glucose sensors, Snf3p and Rgt2p) (5) catalyze arsenite uptake. While most arsenite is taken up by Fps1p in yeast when glucose is present in the medium, approximately 75% goes in by Hxts in the absence of glucose. These fungal glucose transporters are homologues of mammalian GLUT permeases, and we have shown that rat and human GLUT1 and GLUT4 also catalyze uptake of both arsenite and monomethylarsenite (MMA(III)) when heterologously expressed in yeast or frog öocytes (24). GLUT1 is the major glucose permease in erythrocytes and the epithelial cells that form the blood-brain barrier. These results suggest that GLUT1 may be a major pathway uptake of both inorganic and methylated arsenicals in those tissues and might contribute to arsenic-related cardiovascular problems and neurotoxicity. More recently we have shown that mammalian GLUT4, the insulin-responsive isoform, also catalyzes transport of arsenite and MMA(III) (unpublished data). Since neither AQP9 nor GLUT1 can be detected in adult cardiomyocytes by western-blotting (unpublished data), uptake of inorganic and methylated arsenicals into cardiac cells via GLUT4 may be a contributing factor to arsenic-related cardiovascular disease.

Pathways of uptake of Se(VI) and Se(IV)

Little is known about selenium transport, which is the first step in selenium metabolism that includes reduction, methylation, and incorporation into selenoenzymes. Selenate (Se(VI)) is less toxic than selenite (Se(IV)), just as arsenate (As(V)) is less toxic than arsenite (As(III)). Lie the uptake of arsenate by the phosphate ABC transporter, in E. coli selenate uptake is via the sulfate ABC transporter complex encoded by the cysAWTP operon (39, 41). The complex is composed of two CysA ATP-binding proteins, two transmembrane proteins, CysT and CysW, and a periplasmic sulfate binding protein, CysP. Selenite, with two pKa values of 2.46 and 7.31, is a divalent anion at physiological pH. It is also transported by the sulfate permease in E. coli, although substantial uptake remains after repression of that ABC transporter, indicating at least one more uptake system for selenite (41).

In S. cerevisiae sulfate transport mutants in Sul1p and Sul2p were selected by resistance to selenate, indicating that selenate is accumulated by this fungal sulfate permease (8). Similarly, in Aspergillus nidulans, selenate-resistant mutants were found in the Sb gene for the high affinity sulfate permease (32). The homologous sulfate transporter in is SLC26A11 (42).

On the other hand, eukaryotic selenite transporters have not been identified at the molecular level. The kinetics of selenite uptake in yeast suggests the existence of two transport systems: a low affinity system (Km = 435 μM) that is inhibited by glucose and a high affinity system (Km = 54 μM) that is inhibited by glucose (15). Just as arsenite is detoxified by pumping of the As(GS)3 complex into the yeast vacuole (16), selenite is detoxified by sequestration in intracellular compartments (15). Cells of the human chronic mylogenous leukemia line K-562 also have one or more selenite uptake systems (14). However, the carrier proteins that catalyze these uptake reactions have not been identified in either yeast or humans. We have recently shown that the mammalian aquaglyceroporins AQP7 and AQP9 do not serve as channels for selenite even though they effectively conduct arsenite (unpublished data). Therefore arsenite and selenite do not compete at the level of aquaglyceroporins. However, it is not clear if they compete through other uptake pathways such as glucose permeases, a direction of future research efforts.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants GM52216 and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 0520014Z to Z.L.

References

- 1.Abernathy CO, Thomas DJ, Calderon RL. Health effects and risk assessment of arsenic. J Nutr. 2003;133:1536S–8S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1536S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beane Freeman LE, Dennis LK, Lynch CF, Thorne PS, Just CL. Toenail arsenic content and cutaneous melanoma in Iowa. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:679–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behne D, Kyriakopoulos A, Meinhold H, Kohrle J. Identification of type I iodothyronine 5'-deiodinase as a selenoenzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:1143–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharjee H, Rosen BP. Arsenic metabolism in prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbes. In: Nies DHS, Simon, editors. Molecular Microbiology of Heavy Metals. vol. 6. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg/New York: 2007. pp. 371–406. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boles E, Hollenberg CP. The molecular genetics of hexose transport in yeasts. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;21:85–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Berry MJ. Selenium and selenoproteins in the brain and brain diseases. J Neurochem. 2003;86:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng YY, Qian PC. The effect of selenium-fortified table salt in the prevention of Keshan disease on a population of 1.05 million. Biomed Environ Sci. 1990;3:422–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherest H, Davidian JC, Thomas D, Benes V, Ansorge W, Surdin-Kerjan Y. Molecular characterization of two high affinity sulfate transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;145:627–35. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark LC, Combs GF, Jr., Turnbull BW, Slate EH, Chalker DK, Chow J, Davis LS, Glover RA, Graham GF, Gross EG, Krongrad A, Lesher JL, Jr., Park HK, Sanders BB, Jr., Smith CL, Taylor JR. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial. Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. Jama. 1996;276:1957–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colditz GA. Selenium and cancer prevention. Promising results indicate further trials required. JAMA. 1996;276:1984–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combs GF., Jr. Considering the mechanisms of cancer prevention by selenium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;492:107–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1283-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dey S, Rosen BP. Dual mode of energy coupling by the oxyanion-translocating ArsB protein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:385–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.385-389.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster HD. Selenium and cancer prevention. J Nutr. 1988;118:237–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/118.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisk P, Yaqob A, Nilsson K, Carlsson J, Lindh U. Uptake and retention of selenite and selenomethionine in cultured K-562 cells. Biometals. 2000;13:209–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1009272331985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharieb MM, Gadd GM. The kinetics of 75[Se]-selenite uptake by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the vacuolization response to high concentrations. Mycol Res. 2004;108:1415–22. doi: 10.1017/s0953756204001418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh M, Shen J, Rosen BP. Pathways of As(III) detoxification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5001–5006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gourbal B, Sonuc N, Bhattacharjee H, Legare D, Sundar S, Ouellette M, Rosen BP, Mukhopadhyay R. Drug uptake and modulation of drug resistance in Leishmania by an aquaglyceroporin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31010–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Junod AF, Jornot L, Grichting G. Comparative study on the selenium- and N-acetylcysteine-related effects on the toxic action of hyperoxia, paraquat and the enzyme reaction hypoxanthine-xanthine oxidase in cultured endothelial cells. Agents Actions. 1987;22:176–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01968835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohrle J. The trace components--selenium and flavonoids--affect iodothyronine deiodinases, thyroid hormone transport and TSH regulation. Acta Med Austriaca. 1992;19(Suppl 1):13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levander OA. Metabolic interrelationships between arsenic and selenium. Environ Health Perspect. 1977;19:159–64. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7719159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li GS, Wang F, Kang D, Li C. Keshan disease: an endemic cardiomyopathy in China. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:602–9. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin YF, Walmsley AR, Rosen BP. An arsenic metallochaperone for an arsenic detoxification pump. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15617–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603974103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Boles E, Rosen BP. Arsenic trioxide uptake by hexose permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17312–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Sanchez MA, Jiang X, Boles E, Landfear SM, Rosen BP. Mammalian glucose permease GLUT1 facilitates transport of arsenic trioxide and methylarsonous acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu YJ, Wang KL. Pathologic Changes of the Conduction System of the Heart in 43 Cases of Keshan Disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 1964;83:430–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng YL, Liu Z, Rosen BP. As(III) and Sb(III) uptake by GlpF and efflux by ArsB in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18334–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moxon AL. The Effect of Arsenic on the Toxicity of Seleniferous Grains. Science. 1938;88:81. doi: 10.1126/science.88.2273.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukhopadhyay R, Rosen BP. Arsenate reductases in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):745–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nehru LB, Bansal MP. Effect of selenium supplementation on the glutathione redox system in the kidney of mice after chronic cadmium exposures. J Appl Toxicol. 1997;17:81–4. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199701)17:1<81::aid-jat398>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson MA, Porterfield BW, Jacobs ET, Clark LC. Selenium and prostate cancer prevention. Semin Urol Oncol. 1999;17:91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Persson BL, Petersson J, Fristedt U, Weinander R, Berhe A, Pattison J. Phosphate permeases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: structure, function and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1422:255–72. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pilsyk S, Natorff R, Sienko M, Paszewski A. Sulfate transport in Aspergillus nidulans: a novel gene encoding alternative sulfate transporter. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44:715–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez-Solis A, Mukopadhyay R, Rosen BP, Stemmler TL. Experimental and theoretical characterization of arsenite in water: insights into the coordination environment of As-O. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:2954–2959. doi: 10.1021/ic0351592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rayman MP. Selenium in cancer prevention: a review of the evidence and mechanism of action. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:527–42. doi: 10.1079/pns2005467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg H, Gerdes RG, Chegwidden K. Two systems for the uptake of phosphate in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1977;131:505–11. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.2.505-511.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE, Swanson AB, Hafeman DG, Hoekstra WG. Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science. 1973;179:588–90. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4073.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders OI, Rensing C, Kuroda M, Mitra B, Rosen BP. Antimonite is accumulated by the glycerol facilitator GlpF in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3365–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3365-3367.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrauzer GN. Selenium. Mechanistic aspects of anticarcinogenic action. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1992;33:51–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02783992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sirko A, Hryniewicz M, Hulanicka D, Bock A. Sulfate and thiosulfate transport in Escherichia coli K-12: nucleotide sequence and expression of the cysTWAM gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3351–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3351-3357.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stadtman TC. Biosynthesis and function of selenocysteine-containing enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner RJ, Weiner JH, Taylor DE. Selenium metabolism in Escherichia coli. Biometals. 1998;11:223–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1009290213301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vincourt JB, Jullien D, Amalric F, Girard JP. Molecular and functional characterization of SLC26A11, a sodium-independent sulfate transporter from high endothelial venules. Faseb J. 2003;17:890–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0787fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Phelan SA, Forsman-Semb K, Taylor EF, Petros C, Brown A, Lerner CP, Paigen B. Mice with targeted mutation of peroxiredoxin 6 develop normally but are susceptible to oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25179–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whanger PD. Metabolic interactions of selenium with cadmium, mercury, and silver. Adv Nutr Res. 1985;7:221–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2529-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams PN, Raab A, Feldmann J, Meharg AA. Market basket survey shows elevated levels of As in South Central U.S. processed rice compared to California: consequences for human dietary exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:2178–83. doi: 10.1021/es061489k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willsky GR, Malamy MH. Characterization of two genetically separable inorganic phosphate transport systems in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:356–65. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.356-365.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willsky GR, Malamy MH. Effect of arsenate on inorganic phosphate transport in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:366–74. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.366-374.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wysocki R, Chery CC, Wawrzycka D, Van Hulle M, Cornelis R, Thevelein JM, Tamas MJ. The glycerol channel Fps1p mediates the uptake of arsenite and antimonite in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1391–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu C, Rosen BP. Metalloregulation of soft metal resistance pumps. In: Sarkar B, editor. Metals and Genetics. Plenum Press; New York: 1999. pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan J, Barrett JN. Purification from bovine serum of a survival-promoting factor for cultured central neurons and its identification as selenoprotein-P. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8682–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08682.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng H. Arsenic suppresses necrosis induced by selenite in human leukemia HL-60 cells. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2001;83:1–15. doi: 10.1385/BTER:83:1:01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]