Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the effects of 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP), a stable superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimic compound, on oxidative stress markers and endothelial dysfunction in diabetic rats.

ANIMALS AND METHODS:

Rats were made diabetic by a single vein injection of streptozotocin (65 mg/kg) and diabetes was verified by the existence of excessive hyperglycemia a week after the treatment. Control and diabetic rats received vehicle or drug for eight weeks, after which the vascular tissue was examined for relaxation and oxidative stress markers.

RESULTS:

Diabetic rats showed increased vascular levels of superoxide that were accompanied by increased tissue levels of the oxidative stress markers malondialdehyde (MDA) and 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (8-ISO). The vasorelaxant as well as the cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP)-producing effects of acetylcholine (ACh) and nitroglycerine were reduced in diabetic rats. Treatment of diabetic rats with CP (50 mg/kg intraperitoneally, bid) abolished not only the differences in superoxide, MDA and 8-ISO levels, but also the differences in the relaxation and cGMP responses of vascular tissue between control and diabetic rats to both ACh and nitroglycerine.

CONCLUSIONS:

These results support the involvement of reactive oxygen species in mediation of diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction in vivo, and provide the rationale for the potential use of SOD mimics in the treatment of diabetes.

Keywords: cGMP, Endothelial dysfunction, Isoprostanes, Lipid peroxidation, Nitric oxide, Relaxation, Superoxide

The endothelium plays a pivotal role in modulating the vascular tone through the formation and release of several vasoactive compounds. Impairment of endothelial function (ie, endothelial dysfunction) has long been suggested to underlie the micro- and macrovascular complications accompanying diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia and hypertension (1,2). In DM, ample evidence exists to support the key role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mediation of this dysfunction. Many studies now point to decreased endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to acetylcholine (ACh) and other humoral substances in both conduit (3,4) and resistance (5,6) of blood vessels of experimental diabetic animals. In fact, this widespread defect in endothelial function has now been documented in humans in both type I (7,8) and type II (9) diabetes. Although the early changes in endothelial cell function in DM may be related to a change either in nitric oxide (NO) release or its response (10), with a longer duration of disease, both NO release and action are impaired (11,12). The exact reasons for the decreased response to NO in DM are not yet known. However, evidence exists to support the involvement of superoxide and other ROS in the increased destruction of NO released from endothelium or NO derived in the normal course of degradation of nitrovasodilators (13).

At the drug discovery level, however, studies of the in vivo effects of antioxidants on vascular complications accompanying DM are both scanty and controversial. For example, vitamin E was shown to improve insulin action and to reduce oxidative stress in patients with type II DM (14,15). Yet it has recently been reported that this reduction of oxidative stress by vitamin E not only does not prevent endothelial dysfunction, but also may by itself impair vascular function in streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic rats (16). Similarly, although evidence exists to support the key role of superoxide in mediation of hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction and its attenuation by superoxide dismutase (SOD) preparations in vitro, very few reports have addressed the effects of such preparations in vivo.

Here we report the effects of long term administration of the nitroxide 3-carboxy-PROXYL (CP) on endothelial dysfunction accompanying DM. CP is a chemically stable, cell-permeable, nonimmunogenic and potentially nontoxic nitroxide that has been shown to possess powerful SOD mimic activity (17–20) and to inhibit hydroxyl radical formation (21).

ANIMALS AND METHODS

Animals and drugs

All animal experiments described here were reviewed and approved by the Committee on Animal Care of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. ACh, phenylephrine (PE), CP and STZ were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (Sigma, Israel). Solutions were prepared in distilled water or buffer just before use. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Hebrew University, 200±20 g) were randomly divided into three groups: diabetic, control and CP-treated diabetic rats. Rats were made diabetic by a single tail vein injection of STZ (60 mg/kg) dissolved in citrate buffer (0.01 M solution, pH 4.6). Age-matched control rats were injected with the buffer solution alone. A week after STZ treatment, a blood sample was obtained from the tail vein of fasting rats for glucose measurement and diabetes was verified by the existence of hyperglycemia. Randomly selected STZ-treated diabetic rats received CP (50 mg/kg intraperitoneally) twice a day (08:00 and 20:00) starting a week after STZ treatment (CP-treated rats) and throughout the diabetic period with food and water provided ad libitum until the day of study.

Preparation of tissue

Eight weeks after induction of diabetes, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (50 and 10 mg/kg, respectively). A section of the thoracic aorta between the aortic arch and diaphragm was removed and, with care taken not to damage the endothelial cell layer, dissected free of fat and connective tissue in oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Krebs-Henseleit solution (pH 7.4) of the following composition (mM): NaCl 144.0, KCl 5.9, CaCl2 1.6, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25.0 and D-glucose 11.1). Rings of approximately 3 mm in width were then cut, mounted between two stainless steel wires and hooked in 10 mL bath chambers containing continuously oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit solution. The rings were equilibrated at 37°C for 2 h under a resting tension of 2 g with bath fluid being changed every 30 min. Isometric tension was measured with a force-displacement transducer and recorded online using a computerized system (Experimetria Ltd, Hungary).

After equilibration, rings were contracted with PE (5×10–7 M) and concentration-response curves for ACh and nitroglycerine (NTG) were constructed by cumulative addition (10−10 to 10−5 M) of the drugs. Contractile response is expressed as a percentage of the maximal PE contraction and the −log[EC50] values calculated from individual log concentration-response curves. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s unpaired t test for comparison between two groups and applying the one-way analysis of variance for comparison between the three groups with statistical significance set at the level of 5%.

Cyclic GMP

Rings were treated as for the relaxation studies. ACh or NTG (10–6 M) was added to the chamber and, 1 min after exposure to the drug, the rings (usually two to four) were taken, wrapped with aluminum foil and immediately frozen at liquid nitrogen temperature and stored. At the time of analysis, rings were thawed, blotted over a dry gauze and weighed. A known weight of tissue was homogenized in 2 mL ice-cold modified Hank’s balanced salt solution consisting (in g/L) of NaCl 8, KCl 0.4, glucose 1, KH2PO4 0.06, Na2HPO4 0.047, and phenol red 0.017 and containing 25 mM EDTA (disodium salt). The homogenate was centrifuged at 4000 g for 10 min at 2 to 4°C and the supernatant transferred into a fresh precooled test tube containing 1 mL of acetonitrile. The tubes were vortex mixed for a few seconds and subsequently centrifuged at 4000 g for 5 min at 2 to 4°C to remove the precipitated protein. Each supernatant was transferred into a clean test tube and evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen at 55°C. The dry residue was reconstituted with 10 volumes of Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 7.5 (0.05 M Tris containing 4 mM EDTA). Aliquots (100 μL of each 5 mL) of the reconstituted solution in duplicate were used for cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP) measurements using Amersham RIA kit. Standard curves were made with six concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 pmol cGMP/tube) and the assay was performed as described previously (22).

Superoxide production

Superoxide production was assayed by measurement of the SOD-inhibitable reduction of ferricytochrome C (23) with some modifications. Ferricytochrome C (final concentration 50 μM) was added to the reaction buffer at room temperature and incubated for 10 min in the presence or absence of SOD (final concentration 25 U/mL) and reaction was terminated by addition of N-ethyl maleimide (0.5 mM). Reduction of ferricytochrome C was measured spectrophotometrically (550 nm) and the amount of super-oxide produced was calculated by dividing the difference in absorbance of the samples with and without SOD by the extinction coefficient (E550 nm=521.1 mM/cm).

8-ISO-prostaglandin F2α

After homogenization, aortic tissue 8-isoproterenol (8-ISO) was extracted and determined by established methods using an enzyme immunoassay (24). Vascular tissue was homogenized, spiked with [3H]-8-ISO, treated at 40°C with 15% KOH for 1 h and acidified to pH 4 with HCl. Total 8-ISO was extracted (chloroform/methanol [9:1] containing 0.005% butylated hydroxytoluene) and further purified on C18 cartridges eluted with ethyl acetate/hexane/2-propanol (70:27:3), which was later evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. Total 8-ISO was assayed using competitive binding with mouse anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G monoclonal antibody in a 96-well plate as essentially described by the manufacturer (Oxford Biomedical, United Kingdom). Samples were assayed in duplicate and corrected for individual recovery of [3H]-8-ISO.

Malondialdehyde content

Levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) were determined by the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reaction (25). Incubation was carried out in triplicate and was terminated by the addition of 0.5 mL of 50% trichloroacetic acid solution, followed by the addition of 1 mL of 0.67% TBA. Samples were then heated in boiling water for 15 min, cooled and centrifuged for 10 min (4000 g at 4°C). The concentration of TBA reaction products in the supernatant was determined fluorometrically (excitation 515, emission 553 nm) against a standard curve prepared with MDA bis(dimethyl acetal).

RESULTS

Relaxation studies

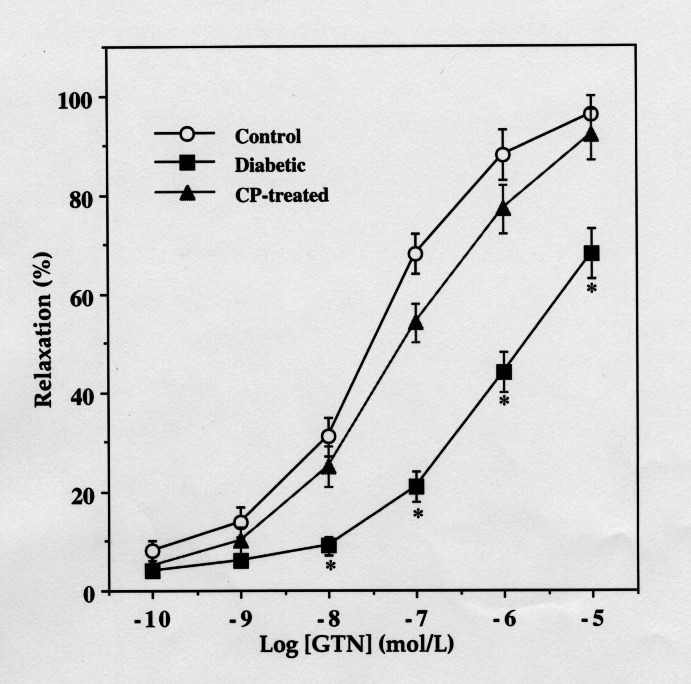

ACh and NTG relaxed aortic rings from all three groups in a concentration-dependent manner. However, the concentration-response curves for both the drugs were significantly shifted to the right in the diabetic nontreated group compared with the control nondiabetic or CP-treated diabetic group (Figure 1). The –log[EC50] values for ACh were 7.513±0.14 and 6.623±0.09 in aortic rings from age-matched control and diabetic rats, respectively (n=8, P<0.001). Similarly, the concentration-dependent relaxation produced by NTG in aorta from diabetic rats was significantly different from those of age-matched control rats and CP-treated diabetic rats (6.521±0.09 versus 7.659±0.15 versus 7.348±0.14, respectively; Figure 2).

Figure 1).

Relaxations of rat aortic rings from control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats in response to acetylcholine (ACh). *Significantly different from the corresponding values of diabetic rats (n=8, P<0.05)

Figure 2).

Relaxations of rat aortic rings from control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats in response to nitroglycerine (NTG). *Significantly different than the corresponding values of diabetic rats (n=8, P<0.05)

Cyclic GMP

Basal concentrations of cGMP in aortic rings from diabetic rats were significantly lower than in rings from CP-treated diabetic rats or age-matched control rats (Figure 3). In all groups, ACh and NTG increased vascular cGMP levels. However, this increase (measured 1 min after drug addition) was significantly lower in nontreated diabetic rats than in age-matched control and CP-treated diabetic rats (Figures 4, 5).

Figure 3).

Basal cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP) levels in rat aortic tissue from control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats. *Significantly greater than in diabetic rats (n=8, P< 0.05)

Figure 4).

Cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP) levels in response to 10–6 M acetylcholine (ACh) of rat aortic tissue from control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats. *Significantly greater than in diabetic rats (n=8, P<0.001)

Figure 5).

Cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP levels (pmol/g wet weight) in response to 10–6 M nitroglycerine (NTG) of rat aortic tissue from control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats. *Significantly greater than in diabetic rats (n=8, P<0.05)

Superoxide and lipid peroxidation

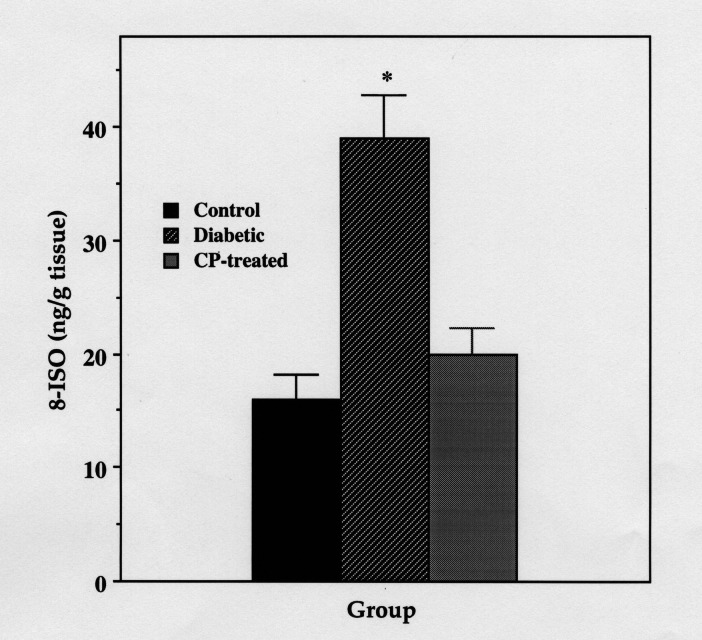

Superoxide production, as well as the levels of two indicators of lipid peroxidation (MDA and 8-ISO), were significantly increased in aorta from diabetic rats as compared with control rats or to CP-treated diabetic rats (Figures 6, 7, 8).

Figure 6).

Basal superoxide production in thoracic aorta from control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats. Data are mean ± SE of four experiments each representing aortas pooled from six rats. *Significantly greater than in control or CP-treated diabetic rats (P<0.001)

Figure 7).

Aortic 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (8-ISO) content of control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats. Data are mean ± SE of four experiments each representing aortas pooled from six rats. *Significantly greater than in control or CP-treated diabetic rats (P<0.001)

Figure 8).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content in aorta from control, diabetic and 3-carbamoyl-PROXYL (CP)-treated diabetic rats. Data are mean ± SE of four experiments each representing aortas pooled from six rats. *Significantly greater than in control or CP-treated diabetic rats (P<0.001)

Effects of CP

Long term treatment of diabetic rats with 50 mg/kg of CP significantly enhanced the vasorelaxant and cGMP-producing effects of the endothelium-dependent vasodilator ACh (Figures 1, 4), as well as those of the nonendotheliumdependent nitrovasodilator NTG (Figures 2, 5). CP itself did not increase basal cGMP production of aorta from control rats in a statistically significant manner (data not shown), but a statistically significant increase in both basal and drug-induced (ACh and GTN) cGMP production was observed in aorta from CP-treated diabetic rats (Figures 3, 4, 5). In addition, CP significantly decreased superoxide production in vascular tissue of diabetic rats. This decrease in superoxide production was accompanied by a significant decrease in vascular tissue content of the oxidative stress markers MDA and 8-ISO. These results demonstrate the ability of CP to abolish the differences in relaxation response and cGMP production between aorta from control and diabetic rats, most likely by mimicking endogenous SOD. This is directly supported by the significantly lower levels of superoxide measured in aorta from CP-treated versus nontreated diabetic rats. This decrease in vascular superoxide is concomitantly accompanied by a decrease in the tissue content of ROS-mediated reaction products (MDA and 8-ISO).

DISCUSSION

Prevention of the vascular complications accompanying DM by inhibition of the hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress constitutes a major clinical challenge in the management of diabetes. Upon oxidation, glucose generates reactive ketoaldehydes, free radicals and superoxide, which, upon further chemical and metabolic reactions, bring about the formation of other free radicals and ROS. These may largely participate in the formation of glycated proteins, which themselves constitute a source of superoxide and hence of other oxygen free radicals (26,27). In fact, a strong correlation between plasma glucose and superoxide concentrations in both normal and diabetic subjects over a wide range of glucose concentrations has been reported (14,15,28). The possibility that ROS play a role in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of diabetes is also suggested by studies showing that antioxidants such as vitamin E, SOD, catalase, glutathione and ascorbic acid are all decreased in the blood and tissue of diabetic animals (29–31). This decrease in endogenously occurring antioxidants also results in increased oxidative injury by failure of protective mechanisms. Increased flux of glucose through the polyol pathway, which is hyperactive in hyperglycemia (31), may deplete NADPH, which is required for generation of NO from arginine (32).

The mechanisms by which ROS may contribute to abnormalities in NO action are diverse. Superoxides may react destructively with NO and limit its biological activity (33). Superoxide production may lead to the formation of hydroxyl radicals, which may be cytotoxic to endothelial cells through direct peroxidation of lipids and proteins (34). Endothelial cell-platelet interactions are also altered in the presence of superoxide anion. For example, thrombin-induced platelet adherence to endothelial cell monolayers is dramatically increased after endothelial cell exposure to superoxide, suggesting that inactivation of NO may have important implications for local platelet deposition (35). Furthermore, superoxide reacts rapidly with NO to form peroxynitrite, which, in addition to mediating the formation and release of vasoconstrictors such as 8-ISO, is a potent oxidant that can transfer oxygen atoms, initiate lipid peroxidation, generate hydroxyl radicals, and oxidize protein tyrosine residues and sulfhydryls, thereby impairing vascular function (36–38).

Because native SOD has limited membrane permeability and has proved to be disappointing in preventing adverse effects of superoxide accompanying DM in vivo, alternative agents with SOD mimetic activity have been investigated. However, some SODs such as CuZn SOD are metal-dependent and become ineffective intracellularly because of metal-legand dissociation. Therefore, compounds with SOD-like activity having low molecular weight, biological stability, no toxicity and membrane permeability are preferred for use in vivo. CP is a stable, metal-independent, low molecular weight SOD mimetic with excellent cell permeability that possesses activity both at the membrane level and in the aqueous phase (17–20,39). In fact, unlike other antioxidants, nitroxides were proved useful for the restoration of the response to ACh of endothelium made dysfunctional by in vitro exposure to oxidant stress (40,41), and it has very recently been shown that in vivo administration of stable SOD mimics such as CP can normalize blood pressure and renal vascular resistance in spontaneously hypertensive rats (42,43).

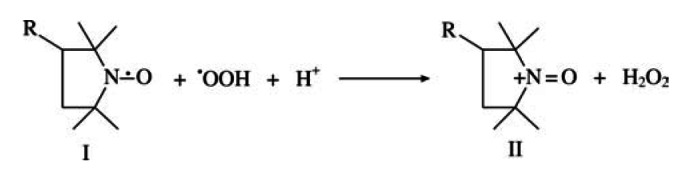

Our in vivo results show that long term administration of the SOD mimic CP protects against diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction, and thus offers a convenient alternative agent that can compensate for the loss of native SOD activity known to accompany DM. The mechanism(s) by which nitroxide antioxidants such as CP exert their antisuperoxide activity is still controversial. The controversy mainly concerns the definition of nitroxides as being either stoichiometric scavengers or true SOD mimics (44). Yet it is universally accepted that they do possess effective antioxidant activity in various biological systems ranging from molecular and cellular to laboratory animal level. Nitroxides are reported to catalyze superoxide dismutation through two different catalytic pathways including reductive and oxidative reaction mechanisms (45). In the case of CP (I), it is readily oxidized by protonated superoxide, •OOH, to yield oxoammonium cation (II):

which in turn oxidizes another superoxide to molecular oxygen:

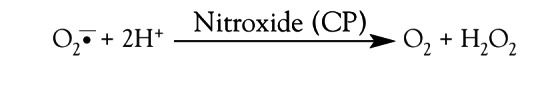

Alternatively, CP may react with superoxide in a catalytic process characterized by a steady state distribution of nitroxide and hydroxylamine (III) and a continuous formation of O2 and H2O2 (46). This SOD mimic, redox-couple actions of CP can be described as follows:

The net reaction, as in the case of native superoxide dismutase, involves the removal of superoxide without affecting nitroxide concentration (47):

Besides the catalytic dismutation of superoxide, nitroxides were reported to reduce hypervalent metals such as ferryl and to remove H2O2 by heme-protein catalysis (47,48), oxidize reduced metals such as Fe2+ or Cu+ and semiquinones to their parent quinones (49,50), and act as chain-breakers and terminators of radical chain reactions, including those involving peroxynitrite and other NO-derived radicals (51). Therefore, one may explain the beneficial effects of CP in DM to be due to multimechanistic, antioxidative stress actions. In addition to direct detoxification of superoxide, these actions may consist of inhibiting superoxide-dependent generation of other ROS (ie, H2O2, peroxynitrite and hydroxyl radicals) either directly or via pseudocatalytic removal of metals. Indirectly, these actions also modulate NO levels by inhibiting its major inactivators. Of these, inhibition of peroxynitrite formation may have the largest impact because its effects on endothelial function are dual. First, CP may prolong the half-life of NO and thus allow it to exert a more powerful vasodilatory action. Second, by blocking its formation, CP may inhibit the peroxynitritemediated production and activation of vasoconstrictor endoperoxides such as 8-ISO (52). These mechanisms may equally be valid in the case of the endotheliumindependent nitrovasodilator NTG. Here, however, the fact that CP augmented relaxation to NTG of diabetic aorta (but not of control aorta) unmasks an additional component of NTG-induced relaxation, which is specifically modified by SOD mimic-treated diabetic endothelium. Thus, the accumulation of superoxide and other ROS in DM may interfere with NO action regardless of the source of this NO, and may therefore underlie the reduced effect of endogenous and exogenous NO on diabetic aortic rings observed in this study. Another possibility may exist that concerns the effects of ROS on guanylyl cyclase activity. This seems reasonable because the activity of this enzyme is thiol dependent, and inhibition of ROS-mediated oxidation of vital SH groups on the enzyme may play a role in CP activity. This is especially true because the intimate relationship between ROS, NO and reduced thiols has already been documented (53,54). Our results showing a decreased basal cGMP production in diabetic aorta, which is restored to control values upon treatment with CP, are in agreement with this possibility.

In summary, long term administration of the stable, nontoxic, membrane-permeable SOD mimetic CP protected rats against diabetes-induced reduction of vascular response to endothelium-dependent and non-dependent NO-mediated vasodilatory action. The effectiveness of CP, as compared with the recently reported lack of effect of vitamin E (16), may be due to the fact that, unlike vitamin E, which scavenges hydroxyl radicals only in the membrane, CP is capable of directly scavenging superoxide and hydroxyl radicals and indirectly affecting other ROS at the membrane domain both intracellularly and extracellularly. By doing so, CP not only increases NO availability by inhibiting its destruction by these ROS, but also prevents the formation of hazardous peroxyl radicals and vasoconstrictors. However, because the effects on the vascular tissue brought about directly by superoxide or indirectly by other ROS generated from superoxide are complex, or yet because of the possible involvement of ROS in either guanylyl cyclase or NO-synthase activity, the exact contribution of these pathways requires further investigation. Regardless of the outcome of such mechanistic investigations, this in vivo study provides the rational basis for potential use of nitroxides such as CP for the prevention of the vascular complications accompanying DM.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. The special support of the Yedidut Foundation of Mexico is also acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Paolisso G. Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: Which role for oxidative stress? Metabolism. 1995;44:363–8. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon RO., III Role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular disease: focus on the endothelium. Clin Chem. 1988;44:1809–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oyama Y, Kawasaki H, Hattori Y, Kanno M. Attenuation of endothelium-dependent relaxation in aorta from diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;131:75–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pieper GM, Gross GJ. Oxygen free radicals abolish endothelium-dependent relaxation in diabetic aorta. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H825–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.4.H825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diederich D, Skopec J, Diederich A, Dai FX. Endothelial dysfunction in mesenteric resistance arteries of diabetic rat: role of free radicals. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1153–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.3.H1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tayler PD, Graves JE, Poston L. Selective impairment of ACh-mediated endothelium-dependent relaxation in isolated resistance arteries of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Clin Sci. 1995;88:519–34. doi: 10.1042/cs0880519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnstone MT, Creager SJ, Scales KM, Cusco JA, Lee BK, Creager M. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 1993;88:2510–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNally PG, Watt PA, Rimmer T, Burdern AC, Hearnshaw JR, Thurston H. Impaired contraction and endothelium-dependent relaxation in isolated resistance vessels from patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Clin Sci. 1994;87:313–36. doi: 10.1042/cs0870031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McVeigh GE, Brennan GM, Johnston GD. Impaired endothelium-dependent and independent vasodilation in patient with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1992;35:771–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00429099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hattori Y, Kawasaki H, Abe K. Superoxide dismutase recovers altered endothelium-dependent relaxation in diabetic rat aorta. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H1049–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.4.H1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abiru T, Wataanabe Y, Kamata K. Decrease in endothelium-dependent relaxation and levels of cyclic nucleotides in aorta from rabbits with alloxan-induced diabetes. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1990;68:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamata K, Miyata N, Abiru T. Functional changes in vascular smooth muscle and endothelium of arteries during diabetes mellitus. Life Sci. 1992;50:1379–87. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90256-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tesfamariam B, Cohen RA. Free radicals mediate endothelial cell dysfunction caused by elevated glucose. Am J Physiol. 1992;90:H727–32. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceriello A, Giugliano D, Quatraro A. Metabolic control may influence the increased superoxide generation in diabetic serum. Diabet Med. 1991;8:540–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1991.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paolisso G, D’amore A, Giugliano D. Pharmacological doses of vitamin E improve insulin action in healthy subjects and non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57:650–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer AM, Thomas CR, Gopaul N, et al. Dietary antioxidant supplementation reduces lipid peroxidation but impairs vascular function in small mesenteric arteries of the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Diabetologia. 1998;41:148–56. doi: 10.1007/s001250050883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell JB, Samuni A, Krishna MC, et al. Biologically active metal-independent superoxide dismutase mimics. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2802–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00463a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell JB, DeGraff W, Kaufman D, et al. Inhibition of oxygen-dependent radiation-induced damage by nitroxide superoxide dismutase mimic, tempol. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;289:62–70. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90442-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samuni A, Winkelsberg D, Pinson A, Hahn SM, Mitchell JB, Russo A. Nitroxide stable radicals protect beating cardiomyocytes against oxidative damage. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1526–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI115163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krishna CM, Samuni A. Nitroxide as antioxidants. Methods Enzymol. 1991;234:580–9. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)34130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charloux C, Paul M, Losiance D, Astier A. Inhibition of hydroxyl radical production by lactobionate, adenine and TEMPOL. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:699–704. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00079-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haj-Yehia AI, Benet LZ. Dissociation of tissue thiol content from nitroglycerin-induced cGMP increase and the state of tolerance. In vivo experiments in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heim KF, Thomas G, Pamwell PW. Superoxide production in the isolated rabbit aorta and the effect of alloxan, indomethacin and nitrovasodilators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;256:537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts LJ, Morrow JD. The generation and actions of isoprostanes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1345:121–35. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(96)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yagi K. A simple fluorometric assay for lipoperoxide in blood plasma. Biochem Med. 1975;15:212–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(76)90049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillery P, Monboisse JC, Maquat FX. Glycation of proteins as a source of superoxide. Diabet Metab. 1988;14:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakurai T, Tsuchiya S. Superoxide production from non-enzymatically glycated proteins. FEBS Lett. 1988;236:406–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collier A, Wilson R, Bradley H. Free radical activity in type-2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 1990;7:27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1990.tb01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karpen CW, Cataland S, O’dorisio TM, Panganamala RV. Production of 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and Vit E status in platelets from type I human diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 1985;34:526–31. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.6.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wohaieb SA, Godin DV. Alteration in free radicals tissue-defense mechanisms in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetes. 1987;36:1014–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.9.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLennan S, Yue DK, Fisher E, et al. Deficiency of ascorbic acid in experimental diabetes. Relationship with collagen and polyol pathway abnormalities. Diabetes. 1988;37:359–61. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Änggård EE. Nitric oxide; mediator, murderer, and medicine. Lancet. 1994;343:1199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gryglewski RJ, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–6. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, et al. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implication for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shatos MA, Doherty JM, Hoack JC. Alteration in human vascular endothelial cell function by oxygen free radical. Platelet adherence and prostacyclin release. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:594–601. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM, Freeman BA. Peroxynitrite oxidation of sulfhydryls. The cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4244–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huie RE, Padmaja S. The reaction of NO with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun. 1993;18:195–9. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myatt L, Rosenfield RB, Eis AL, Brockman DE, Greer I, Lyall F. Nitrotyrosine residues in placenta: evidence for peroxynitrite formation and action. Hypertension. 1996;28:488–93. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gelvan D, Saltman P, Powell SR. Cardiac reperfusion damage prevented by a nitroxide free radical. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4680–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mok JS, Paisley K, Martin W. Inhibition of nitrergic neurotransmission in the bovine retractor penis muscle by an oxidant stress: Effects of superoxide dismutase mimetics. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:111–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacKenzie A, Martin W. Loss of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in rabbit aorta by oxidant stress: restoration by superoxide dismutase mimetics. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:719–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnackenberg CG, William JW, Wilcox CS. Normalization of blood pressure and renal vascular resistance in SHR with a membrane-permeable superoxide dismutase mimetic. Role of nitric oxide. Hypertension. 1998;32:59–64. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnackenberg CG, Wilcox CS. Two-week administration of Tempol attenuates both hypertension and renal excretion of 8-Iso prostaglandin F2a. Hypertension. 1999;33:424–8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishna CM, Russo A, Mitcell JB, Goldstein S, Dafni H, Samuni A. Do nitroxide antioxidants act as scavengers of O2- or as SOD mimics? J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26026–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krishna CM, Grahame DA, Samuni A, Mitchell JB, Russo A. Oxoammonium cation intermediate in the nitroxide-catalyzed dismutation of superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5537–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samuni A, Krishna CM, Riesez P, Finkelstein E, Russo A. A novel metal-free low molecular weight superoxide dismutase mimic. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17921–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehlhorn RJ, Swanson CE. Nitroxide-stimulated H2O2 decomposition by peroxidases and pseudoperoxidases. Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;17:157–75. doi: 10.3109/10715769209068163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krishna CM, Samuni A, Taira J, Golsstein S, Mitchell JB, Russo A. Stimulation by nitroxides of catalase-like activity of hemeproteins. Kinetics and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26018–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samuni A, Krishna CM, Mitchell JB, Collins CR, Russo A. Superoxide reaction with nitroxide. Free Radic Res Commun. 1990;9:241–9. doi: 10.3109/10715769009145682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuni A, Min A, Krishna CM, Mitchell JB, Russo A. SOD-like activity of 5-membered ring nitroxide spin labels. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1990;264:85–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5730-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nilson UA, Olsson LI, Carlin G, Bylund FA. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation by spin labels. Relationships between structure and function. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Landino LM, Crews BC, Timmons MD, Morrow JD, Mamet LJ. Peroxynitrite, the coupling product of nitric oxide and superoxide, activates prostaglandin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ignarro LJ, Kadowitz P, Baricos W. Evidence that regulation of hepatic guanylate cyclase activity involves interaction between catalytic site -SH groups and both substrate and activator. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;208:75–86. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kontos HA, Wei WP. Hydroxyl radical-dependent inactivation of guanylate cyclase in cerebral arterioles by methylene blue and by LY83583. Stroke. 1983;24:427–34. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]