Abstract

The pyrimidine antimetabolite 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a chemotherapeutic agent used widely for various tumors. Common side effects of 5-FU are related to its effects on the bone marrow and gastrointestinal epithelium. Neurotoxicity caused by 5-FU is uncommon, although acute and delayed forms have been reported. Wernicke's encephalopathy is an acute, neuropsychiatric syndrome resulting from thiamine deficiency, and has significant morbidity and mortality. Central nervous system neurotoxicity such as Wernicke's encephalopathy following chemotherapy with 5-FU has been reported rarely, although it has been suggested that 5-FU can produce adverse neurological effects by causing thiamine deficiency. We report a patient with Wernicke's encephalopathy, reversible with thiamine therapy, associated with 5-FU-based chemotherapy.

Keywords: Fluorouracil, Wernicke's Encephalopathy, Thiamine

INTRODUCTION

Neurotoxicity, especially peripheral neuropathy, is a common adverse effect of cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents, but central nervous system (CNS) toxicity is relatively uncommon. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), a fluorinated pyrimidine, is an antineoplastic antimetabolite first introduced in 1958 that is used in the treatment of various solid cancers such as carcinoma of the colon, rectum, breast, stomach, and pancreas (1). This fluorinated pyrimidine is metabolized inside the cells to 5-fluoro-2-deoxyuridine-5-phosphate, which inhibits thymidylate synthase. Blockade of this enzyme inhibits DNA synthesis. Common side effects of 5-FU are related to its effects on the bone marrow (leukopenia) and gastrointestinal epithelium (stomatitis, esophagopharyngitis, diarrhea, anorexia, nausea, vomiting) (2). However, neurotoxicity is uncommon with 5-FU-based chemotherapy (3). Wernicke's encephalopathy, an acute neuropsychiatric syndrome that results from thiamine deficiency, has rarely been associated with 5-FU-treatment. Here, we report a patient who developed imaging-documented Wernicke's encephalopathy following 5-FU-based chemotherapy and who recovered after stopping therapy.

CASE REPORT

A 46-yr-old woman was diagnosed with nasopharyngeal cancer 5 months before being admitted to our hospital for a course of chemotherapy. She had no history of chronic alcohol consumption or benzodiazepine addiction, or any other significant medical history including malnutrition, surgery or herbal medications. There were no laboratory abnormalities. Concurrent chemoradiation therapy was performed with cisplatin (100 mg/m2 at 3-week intervals). One month after the completion of concurrent chemoradiation therapy, we gave her chemotherapy consisting of a continuous infusion of 5-FU 1,000 mg/m2/day for 4 days and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 for 1 hr on the first day of each chemotherapy cycle at 3-week intervals. She experienced NCI CTC (v. 3.0) grade 2 stomatitis and grade 3 neutropenia during the first cycle, which resolved after supportive therapy. There was no diarrhea or vomiting of significant grade.

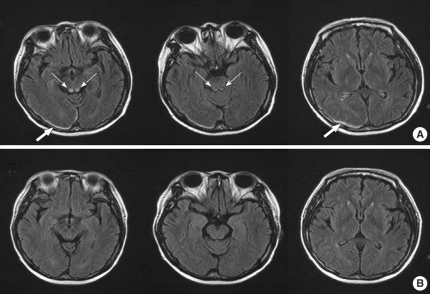

On the 20th day of the second round of chemotherapy with 5-FU and cisplatin, she experienced dizziness with nystagmus, but these symptoms resolved with conservative management. Fifteen days after the dizziness episode, she showed acute onset disorientation, headache, and lethargy. Her mental status showed confusion, but neither focal neurological signs nor pathological reflexes were noted. Her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, pulse rate 110/min, respiratory rate 14/min, and body temperature 36.4℃. Her myelosuppression status after chemotherapy was a white blood cell count of 1,300/µL (neutrophils 74.4%, lymphocytes 14.3%), hemoglobin concentration of 8.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 62,000/µL. At that time, the level of serum BUN and creatinine were 10 mg/dL and 0.6 mg/dL. Her serum sodium and potassium were 133 and 3.5 mM/L, respectively. The total protein was 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 6.5-8.4 g/dL), serum albumin 3.6 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.1 g/ dL), triglyceride 67 mg/dL (reference range, 28-150 mg/dL), cholesterol 68 mg/dL (reference range, 130-240 mg/dL), and magnesium 1.9 mg/dL (reference range, 1.9-3.1 mg/dL). The body weight of the patient at diagnosis was 52 kg and was 54 kg at the time of this event. Her serum folic acid concentration was 2 ng/mL (reference range, 3-17 ng/mL), vitamin B12 concentration 1,259 pg/mL (reference range, 253-1,090 pg/mL), and thiamine concentration 138.1 ng/dL (reference range, 21.3-81.9 ng/dL). The ammonia concentration was normal. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed symmetrical high signal intensities in the posterior aspect of the medulla and periaqueductal area of the midbrain that were consistent with Wernicke's encephalopathy. A small amount of subdural hematoma in the right posterior occipital area was noted (Fig. 1A). She was given intravenous thiamine, 500 mg for 5 days, and then oral thiamine, 60 mg/day, even though the initial serum thiamine level was normal. Her confused mental state resolved after several hours, and her dizziness and nystagmus gradually improved over the next 5 days.

Fig. 1.

(A) The initial MRI demonstrates symmetric high signal intensities in the posterior aspect of the medulla and the periaqueductal area of the midbrain (narrow arrows) and an occipitoparietal hematoma (broad arrows). Axial FLAIR. (B) Follow-up MRI 1 month later shows nearly complete resolution of the previous abnormal signal intensities in the posterior aspect of the medulla, the periaqueductal area of the midbrain, and the occipitoparietal hematoma.

The brain MRI was repeated in the outpatient clinic 1 month after the episode. The MRI showed nearly complete resolution of the previous abnormal signal intensities in the posterior aspect of the medulla and the periaqueductal area of the midbrain, including the subdural hematoma (Fig. 1B).

DISCUSSION

Neurotoxicity is an uncommon side effect of 5-FU therapy. There are two types of toxicity, classified according to the time of onset of symptoms. Acute toxicity manifests as a diffuse encephalopathy or a cerebellar syndrome, is dose-related, and is generally self-limiting. Delayed toxicity appears several months later, is characterized as subacute multifocal leukoencephalopathy, is immune-mediated, and responds to corticosteroid treatment (3, 4). About 5% (range, 0.6-7%) of patients treated with 5-FU experience neurotoxicity (3). In a study by Yeh and Cheng, 5.57% of patients developed 5-FU-related encephalopathy (5).

Wernicke's encephalopathy is characterized by an acute onset of symptoms that may include changes in mental status, ocular abnormalities and motor problems such as uncoordinated gait and ataxia, but this triad of symptoms is seen in only 16% of patients (6). Wernicke's encephalopathy can be caused by thiamine deficiency associated with chronic alcohol abuse, malnutrition or unbalanced nutrition, gastrointestinal surgery, recurrent vomiting, chronic diarrhea, systemic illness, or magnesium depletion, all of which can affect thiamine uptake and utilization (7-9). Wernicke's encephalopathy can be diagnosed primarily from the clinical features, and it should be confirmed by symptomatic improvement with thiamine treatment (10). MRI is currently considered the most valuable method to confirm a diagnosis of Wernicke's encephalopathy. MRI has a sensitivity of 53% and a high specificity of 93%, so it can be used to rule out other disorders. In Wernicke's encephalopathy, MRI studies typically show an increased T2 signal that is bilaterally symmetrical in the paraventricular regions of the thalamus, the hypothalamus, mammillary bodies, the periaqueductal region, the floor of the fourth ventricle, and the midline cerebellum (6).

Wernicke's encephalopathy following chemotherapy with 5-FU has been reported rarely (11). Although the biochemical basis for the neurological toxicity of 5-FU is not fully understood, it may be related to blockade of the Krebs cycle by fluoroacetate, a product of fluorouracil catabolism; another possibility relates to thiamine deficiency. Either possibility means that 5-FU-induced CNS neurotoxicity can manifest as Wernicke's encephalopathy. Thiamine phosphate is the active form of the vitamin, but its formation from thiamine can be blocked by 5-FU, an action that could further exacerbate preexisting thiamine deficiency in cancer patients (3). Askoy et al. prospectively followed 35 patients receiving 5-FU-based chemotherapy and treated thiamine-deficient patients with vitamin supplements (12).

Historically, most 5-FU-associated neuropathies developed during 5-FU infusion or shortly after 5-FU completion. Our patient developed Wernicke's encephalopathy after 5 weeks of initial 5-FU exposure, but at that time, the concentration of thiamine was not low, although this measurement is limited by a lack of specificity and technical difficulties (6). The nutritional status of our patient was improving after several weeks, although her nutritional intake remained lower than normal because of mouth dryness induced by the previous concurrent chemoradiation of the head and neck cancer. It appears that the 5-FU could have caused the Wernicke's encephalopathy in our patient despite the small dietary deficiency, because she was not in severe malnutritional status judging from the total protein, albumin, triglyceride, and magnesium levels and her relatively improving appetite. A deficiency in dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), the rate-limiting enzyme responsible for the catabolism of 5-FU, may be associated with this type of neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, and myelosuppression (4). We did not measure the DPD level in this patient, but the concurrent myelosuppression might reflect her low DPD level indirectly. In addition, cisplatin combined with 5-FU can induce neurotoxicity, but this complication manifests mainly as a peripheral sensory neuropathy, although it may occasionally induce encephalopathy with or without seizure (13), and it has not been reported in relation to thiamine. Our patient was given a higher dose of cisplatin in a previous concurrent chemoradiation stage, but this did not produce any neurological abnormality.

We postulate that this patient had barely escaped the marginal thiamine deficiency during cancer and therapy, and the subsequent exposure to 5-FU aggravated the dietary imbalance and caused the encephalopathy. The clinical neurological symptoms and radiological abnormalities were reversed with adequate replacement of thiamine, which differs somewhat from traditional Wernicke's encephalopathy. Some therapies for malignancy have induced Wernicke's encephalopathy caused by a lack of thiamine supplementation with total parenteral nutrition, fast-growing neoplastic cells, vomiting and poor appetite. Moreover the use of specific chemotherapy agents such as 5-FU and ifosfamide can induce this neurological disorder (6, 14). Thus, it is important to confirm the clinical suspicion of Wernicke's encephalopathy associated with thiamine deficiency in treating cancer patients.

In conclusion, physicians should be aware of neurological signs in cancer patients treated with 5-FU, regardless of the CNS involvement of the tumor, especially if the patient is at risk of dietary deficiency.

References

- 1.Kummar S, Noronha V, Chu E. Antimetabolites. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 7th ed. volume 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 361–364. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sausville EA, Longo DL. Principles of cancer treatment: surgery, chemotherapy and biologic therapy. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. volume 1. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. p. 476. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirzada NA, Ali II, Dafer RM. Fluorouracil-induced neurotoxicity. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:35–38. doi: 10.1345/aph.18425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YA, Chung HC, Choi HJ, Rha SY, Seong JS, Jeung HC. Intermediate dose 5-fluorouracil-induced encephalopathy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:55–59. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh KH, Cheng AL. High-dose 5-fluorouracil infusional therapy is associated with hyperammonaemia, lactic acidosis and encephalopathy. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:464–465. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke's encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:442–455. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attard O, Dietemann JL, Diemunsch P, Pottecher T, Meyer A, Calon BL. Wernicke encephalopathy: a complication of parenteral nutrition diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:847–848. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merkin-Zaborsky H, Ifergane G, Frisher S, Valdman S, Herishanu Y, Wirguin I. Thiamine-responsive acute neurological disorders in nonalcoholic patients. Eur Neurol. 2001;45:34–37. doi: 10.1159/000052086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiossi G, Neri I, Cavazzuti M, Basso G, Facchinetti F. Hyperemesis gravidarum complicated by Wernicke encephalopathy: background, case report, and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61:255–268. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000206336.08794.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo IS, Lee SH, Kim SH, Kim WS, Lee KS, Song SK, Lee WG, Kim EH, Choi YW, Lee YU. A case of acute coma & respiratory arrest in Wernicke's encephalopathy caused by malnutrition . Korean J Med. 1998;55:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo K, Fujiwara M, Murase M, Kodera Y, Akiyama S, Ito K, Takagi H. Severe acute metabolic acidosis and Wernicke's encephalopathy following chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin: case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1996;26:234–236. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jjco.a023220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aksoy M, Basu TK, Brient J, Dickerson JW. Thiamin status of patients treated with drug combinations containing 5-fluorouracil. Eur J Cancer. 1980;16:1041–1045. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(80)90251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steeghs N, de Jongh FE, Sillevis Smitt PA, van den Bent MJ. Cisplatin-induced encephalopathy and seizures. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14:443–446. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong SH, Kim ES, Roh YW, Jung SK, Chung C, Kong HS, Yun CB, Kang SS, Lee SK, Hwang HY, Bang SM, Cho EK, Shin DB, Lee JH. A case of iatrogenic Wernicke's encephalopathy following chemotherapy and total parenteral nutrition. Korean J Hematol. 2001;36:95–99. [Google Scholar]