Abstract

AIM: To determine the outcome of esophageal cancer patients referred for palliative care, in Gorgan and Gonbad gastrointestinal clinics, northeast of Iran.

METHODS: This cross-sectional study was done on inoperable esophageal cancer cases referred to gastrointestinal clinics in Gorgan and Gonbad city (2005-2006). Demographic data were collected during the procedure and cases were followed up every one month. Improvement proportion was calculated with 95% confidence interval, to determine the rate of improvement. Survival analysis and Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate the duration of palliative care effectiveness.

RESULTS: We recruited 39 cases into the study. Squamous cell carcinoma was the most prevalent (92.3%). The middle third of the esophagus was involved predominantly (51.3%). Dilation was the most preferred method (89.7%) and stenting was done in 4 cases. Decreasing dysphagia score was not related to palliation method or pathology type of carcinoma. Age of the patients was significantly related to the improvement of dysphagia score. Mean survival time was 137.6 d and median was 103 d.

CONCLUSION: Results of this study showed a low survival rate after palliative care in esophageal cancer cases despite dysphagia scores’ improvement after dilating or stenting.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, Palliative care, Survival, Dysphagia, Iran

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer patients have poor prognosis. Due to the lack of widespread screening methods, diagnosis is usually made at advanced stages; therefore, they have a short survival when diagnosed. The 5-year survival rate of patients with esophageal cancer is < 20%[1].

This is more obvious especially in some regions like the northeast of Iran, where the prevalence rate of esophageal cancer is high.

Esophageal cancer five-year survival has slightly increased during past 20 years (5%-9%), but still remains low. Most patients present with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic disease. At the time of diagnosis, 60% of the patients are only suitable for palliative therapy. Recent advances in therapeutic endoscopy have allowed improving dysphagia, and quality of life. Endoscopic techniques are chosen according to tumor characteristics, since the diagnosis is often made at an advanced stage, when radical treatment is unfeasible[1–3].

Dysphagia, or the inability to swallow, is one of the most distressing and debilitating symptoms in patients with cancer-related oesophageal obstruction. Dysphagia leads to nutritional compromise, pain, and deterioration of quality of life[1,4,5].

As the quality of life, and to some extent the quantity of life remaining to these patients depends to a large degree on their ability to swallow, the relief of dysphagia plays a vital role in the palliation of this disease[5].

Endoscopic palliation aims to restore swallowing, avoid re-intervention and reduce hospitalization[1,4,5].

Palliation is an important goal of esophageal cancer therapy. Current management options for the palliation of dysphagia include: esophageal dilation, intraluminal stents, Nd:YAG laser therapy, photodynamic therapy, argon laser, systemic chemotherapy, external beam radiation therapy, brachytherapy, and combined chemoradiation therapy. The clinical situation, local expertise, and cost effectiveness play an important role in choosing the appropriate treatment modality[1].

Treatment should ensure that the majority of these patients could avoid the consternation of total dysphagia, regardless of which stent is offered[5].

Palliative treatment methods for esophageal and cardiac cancer include dilation, laser vaporization and other thermal methods, alcohol injection, and stent insertion. None of these procedures, however, has proved to be a simple, well-tolerated, and lasting method[5]. The aim of this study was to determining the rate of recovery after two methods of palliation in patients with inoperable esophageal carcinoma, in Golestan province, northeast of Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This descriptive cross-sectional study was designed in two main and unique clinics of gastroenterology in the province (located in the central and eastern part of Golestan Province) and all inoperable esophageal cancer cases which referred from January 2005 to March 2007 were recruited. A basic checklist was completed for each case before the procedure and their demographic data were registered.

Dysphagia was graded as follows: 0 = able to eat normal diet/no dysphagia; 1 = able to swallow some solid foods; 2 = able to swallow only semi solid foods; 3 = able to swallow liquids only; 4 = unable to swallow anything/total dysphagia[5].

Subjects were followed up every month, and the endpoint was considered as death or finishing the 6-mo period, due to the short survival of them. Improvement in dysphagia was evaluated 1 wk after stent placement and during monthly interviews.

Complications of palliative therapy were defined as major (aspiration, bleeding, stent misplacement or dislocation, perforation) or minor (reflux esophagitis, chest pain, pharyngeal discomfort). Tumor ingrowth or overgrowth was considered a treatment failure[6].

The decrease in dysphagia severity for at least one degree was registered as dysphagia recovery.

After coding data and entering into the computer, improvement proportion was calculated with 95% confidence interval, to determine the rate of improvement. Survival analysis and Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate the duration of palliative care effectiveness.

RESULTS

Thirty and nine cases fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Male to female ratio was 1.6 to 1. Mean age was 67.5 ± 13.7 years. Among these cases, 89.7% were palliated with dilation method, and others (n = 3) with stenting. Most of them (92.3%) were diagnosed as having SCC. The middle third of the esophagus was the most (51.3%) involved site.

At the beginning of the study, 22 cases (56.4%) had grade three dysphagia (dysphagia to water) and other 17 had complete or grade four dysphagia.

At the first follow up (one month after procedure), seven cases were not available (died). They passed away between 6-31 d (Table 1).

Table 1.

Report of dysphagia after palliative care in patients suffering from inoperable esophageal cancer in Golestan province, northeast of Iran

| Dysphagia | Frequency | Percent |

| Recovery | ||

| The first degree | 18 | 46.2 |

| The second degree | 7 | 17.9 |

| No recovery | 4 | 10.3 |

| Dysphagia aggravation | 3 | 7.7 |

| Not available | 7 | 17.9 |

| Total | 39 | 100 |

We considered these deaths as non-recovery of dysphagia, and then categorized the cases into two groups: 1, recovered and 2, not recovered (death, dysphagia aggravation or no change in dysphagia) and evaluated the relation between various variables with this condition (Table 2).

Table 2.

Dysphagia relief after palliative care regarding the different variables in patients suffering from inoperable esophageal cancer in Golestan province, northeast of Iran

| Dysphagia relief | Variables |

No recovery |

Recovery |

||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Type of palliative care | Stent | 1 | 25 | 3 | 75 |

| Dilation | 13 | 37.1 | 22 | 62.9 | |

| Total | 14 | 35.9 | 25 | 64.1 | |

| Age (yr) | < 65 | 3 | 21.4 | 11 | 78.6 |

| ≥ 65 | 10 | 40 | 15 | 60 | |

| Pathology | SCC | 13 | 36.1 | 23 | 63.9 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | |

No significant relation was seen between relieving dysphagia, and method of palliative care or pathology type of the esophageal cancer (P = 0.96). Age of the patients and the dysphagia recovery was not significantly related, too (P = 0.238). Mean dysphagia score was significantly improved in the first follow up (3.37 vs 2.43; 95% CI, 0.62-1.25; P < 0.0001).

Among other 32 cases which were available at the first follow up, 25 were free of dysphagia. Survival analysis method was used to estimate the length of dysphagia relieving persistency after palliation. Aggravation of dysphagia at any time was considered as recurrence.

The mean time of persistent recovery was 172.1 d, and the median was 120 d. Among these 25 patients, only in ten cases no recurrence of dysphagia was reported up to the end of follow-up. At the end of 6-mo follow-up, only 6 (15.4%) patients were alive. The overall mean and median survival time was 137.6 d and 103 d after palliation, respectively.

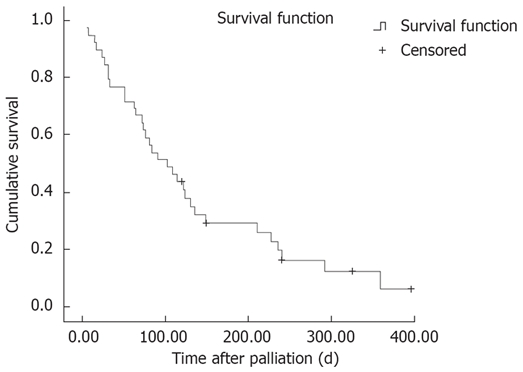

In the recovered group, mean and median survival time were 177.1 d and 135 d after palliation, respectively; while it was 60.7 d and 31 d in the other group; respectively. Kaplan-Meyer survival analysis and Log-rank used to evaluate the relation between dysphagia relief and the survival rate of the cases and significant differences were reported (χ2 = 13.21, P < 0.0001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival function dysphagia recovery after palliative care by Kaplan-Meyer method.

DISCUSSION

Diagnostic and therapeutic management of esophageal cancer is a multidisciplinary challenge. Male to female ratio in our patients was 1.6 to 1. This proportion is reported in other similar studies[5].

The most involved part of the esophagus was the middle third, and SCC was the most prominent type. While, in Western countries, the distal third is involved most[2,3], maybe the higher incidence of adenocarcinoma, and its potentiality to appear in the distal part can explain this discrepancy. Among 39 recruited cases, 25 (64%) reported a relief in dysphagia. One grade decrease in dysphagia was seen in 46.2% and 2 grade in 17.9%.

In a study in France, a total of 120 patients treated in a single center by insertion of SEMS (Self-expanding Metal Stent), dysphagia scores decreased in 89.1% of patients, with median scores decreasing from 3.0 to 1.0 (P < 0.05)[7]. In the present study, mean dysphagia score in the first follow-up decreased significantly compared to pre-operation (from 3.37 to 2.43). Mean survival time after procedure was 177 d (5.9 mo) in recovered group, and 60.7 d (2 mo) in the other group, which was much lower than reported in other studies[8–10].

In a study in the Netherlands (2006), data from 78 patients, rendered incurable at exploration, and who subsequently underwent palliative interventions, were analyzed retrospectively. Overall, intraluminal stenting was the palliative measure of dysphagia in 25 patients (32.3%). The median survival in the whole group was 8.9 (1-105) mo. Patients treated with chemotherapy had a higher median survival of 11.6 mo compared to that of the other palliatively-treated patients: 8.4 mo (P = 0.003). They concluded that patients with incurable oesophageal carcinoma have a poor overall survival of less than 9 mo[8].

In India (2006), thirty patients with inoperable esophageal carcinoma were treated with SEMS. Quality of life score improved significantly from 62-94 before stenting to 80-133 after the procedure. There was improvement in dysphagia grades. Pain was the most common complaint noted on follow up. There was no major morbidity or mortality related to the procedure[11].

In the present study, no complaints were reported immediately after procedure and in the next follow-up, except for the seven cases that reported aggravation or no recovery of dysphagia. One important and disappointing result of this investigation was the high mortality rate of esophageal cancer in our area. Seven deaths occurred between procedures until the first follow-up (one-month later) and at the end of the study, only 6 cases were alive. Ross et al (USA, 2007) studied ninety-seven patients with malignant dysphagia who had SEMS placed from 2000 to 2003. Dysphagia scores improved in 86%. Early unexpected deaths occurred in 2 patients. Adenocarcinoma and female sex were factors associated with increased odds of a major complication. Median survival was 77 d[10].

In the present study, dysphagia aggravation and re-dilation was implicated in 7.7%. This is a usual problem seen in all other investigations[9,11]. In a study in Norway (2006), 37 patients with unresectable esophageal and cardial carcinoma treated with SEMS (January 1997- May 2004) were retrospectively analyzed. One patient died the day the stent was introduced. The median time to repeated hospital contact was 25 d, most often due to recurrence of dysphagia. Ten patients underwent repeated stent insertion. The median survival time after the first stent insertion was 88 d[9].

In an Italian report (2007), in 60 cases with malignant dysphagia due to the various etiologies stent insertion was done. The mean dysphagia score of 2.8 improved to a mean score of 1.0 after stenting (P < 0.001). Overall median survival time was 4.6 mo[4]. In Germany (2007), stent insertion was done in eighteen patients with esophageal carcinoma. Seventeen of 18 stents were placed technically successful in a single endoscopic procedure. Mean dysphagia score improved from 2.2 to 0.6. In 10 patients, a re-intervention was necessary mainly due to dislocation of the stent[12].

Although placement of a stent is technically feasible, its application is hampered by frequent stent migration and insufficient prevention of gastroesophageal reflux. Further technical improvements of stents or alternative methods like brachytherapy are required for satisfactory palliation of malignant gastroesophageal stenosis[12,13].

Comparing dilation and stenting in the present survey showed that dysphagia recovered in 63.6% after dilation and in 75% after stent insertion.

Although, dysphagia relief and median survival rate were lower in our study, maybe due to the delay in referring and the developed stages at the presentation; however, it seems that palliative care is effective in relieving dysphagia of inoperable esophageal carcinoma, and is suggested for increasing quality of life in the remaining life-span of the patients.

Implantation of stents proved to be an effective and safe method in palliating severe dysphagia in patients with obstructing esophageal cancer[14–16]; but dilation seems more popular especially in our area; while stents are more expensive, and dilation is more preferred by patients and physicians.

Larger studies with higher sample size and facilities for screening in the lower dysphagia stages and evaluating other factors that impact on the survival rate of the patients are necessary.

Accurate and expanded results could not be achieved in the present report, due to the unavailability of some data and deaths occurred between the procedure and the first follow-up. Also, all included patients had grade 3 and 4 dysphagia, which can itself have an important impact on survival rate, because of prolonged inability of swallowing and the resulting malnutrition.

COMMENTS

Background

Esophageal cancer 5-year survival has slightly increased during past 20 years (5%-9%), but still remains low. Most patients present with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic disease. At the time of diagnosis, 60% of the patients are only relevant for palliative therapy. As the quality of life, and to some extent the quantity of life remaining to these patients depends to a large degree on their ability to swallow, the relief of dysphagia plays a vital role in the palliation of this disease.

Research frontiers

The clinical situation, local expertise, and cost effectiveness play an important role in choosing the appropriate treatment modality in these patients. Treatment should ensure that the majority of these patients could avoid the consternation of total dysphagia, regardless to which stent is offered.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Although, dysphagia relief and median survival rate were lower in our study, maybe due to the delay in referring and developed stages at the presentation time; however, it seems that palliative care is effective in relieving dysphagia of inoperable esophageal carcinoma, and is suggested for increasing quality of life in the remaining life-span of the patients.

Applications

Implantation of stents proved to be an effective and safe method in palliating severe dysphagia in patients with obstructing esophageal cancer; but dilation seems more popular especially in our area; while stents are more expensive and dilation is more preferred by patients and physicians.

Peer review

Inoperable esophageal cancer cases face many challenges due to the difficulty in eating. When the tumor is considered not resectable, palliative care would be performed to provide a temporary canal for patients. Our area is placed on the esophageal cancer belt of the world, thus, investigators try to determine different aspects of this cancer in the region and help patients have a better life expectancy. Here, we assessed the outcome of esophageal cancer patients which underwent ballooning and stenting as a palliation for their dysphagia.

Acknowledgments

Authors tend to appreciate all who assist us in gathering data from Atrak clinic (Gonbad city) and 5th Azar endoscopy center (Goragn city).

Peer reviewer: Robert J Korst, MD, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Room M404, 525 East 68th Street, New York 10032, United States

S- Editor Zhong XY L- Editor Kremer M E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Javle M, Ailawadhi S, Yang GY, Nwogu CE, Schiff MD, Nava HR. Palliation of malignant dysphagia in esophageal cancer: a literature-based review. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:365–373, 379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrante M, Feliziani M, Imperatori A, Ferraris L, Bernasconi G. Endoscopic palliation of esophageal cancer. Rays. 2006;31:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahan L, Ries P, Laugier R, Seitz JF. [Palliative endoscopic treatments for esophageal cancers] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conigliaro R, Battaglia G, Repici A, De Pretis G, Ghezzo L, Bittinger M, Messmann H, Demarquay JF, Togni M, Blanchi S, et al. Polyflex stents for malignant oesophageal and oesophagogastric stricture: a prospective, multicentric study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:195–203. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328013a418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tate H. The Palliation of Dysphagia in Oesophageal Malignant Obstructions Using Endoprostheses: A Review of the Literature. Vol. 19. Newcastle upon Tyne: Priory Lodge Education Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkelbauer FW, Schofl R, Niederle B, Wildling R, Thurnher S, Lammer J. Palliative treatment of obstructing esophageal cancer with nitinol stents: value, safety, and long-term results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:79–84. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lecleire S, Di Fiore F, Antonietti M, Ben Soussan E, Hellot MF, Grigioni S, Dechelotte P, Lerebours E, Michel P, Ducrotte P. Undernutrition is predictive of early mortality after palliative self-expanding metal stent insertion in patients with inoperable or recurrent esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pultrum BB, van Westreenen HL, Mulder NH, van Dullemen HM, Plukker JT. Outcome of palliative care regimens in patients with advanced oesophageal cancer detected during explorative surgery. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2289–2293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tangen M, Andresen SJ, Moum B, Hauge T. [Stent insertion as palliation of cancer in the esophagus and cardia] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2006;126:1607–1609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross WA, Alkassab F, Lynch PM, Ayers GD, Ajani J, Lee JH, Bismar M. Evolving role of self-expanding metal stents in the treatment of malignant dysphagia and fistulas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maroju NK, Anbalagan P, Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N. Improvement in dysphagia and quality of life with self-expanding metallic stents in malignant esophageal strictures. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoppmeyer K, Golsong J, Schiefke I, Mossner J, Caca K. Antireflux stents for palliation of malignant esophagocardial stenosis. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller R, Flieger D, Fischbach W, Christl SU. Self-expanding metal stents for malignant esophagogastric obstruction: experience with a new design covered nitinol stent. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cwikiel W, Tranberg KG, Cwikiel M, Lillo-Gil R. Malignant dysphagia: palliation with esophageal stents--long-term results in 100 patients. Radiology. 1998;207:513–518. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.2.9577503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carreira Villamor JM, Reyes Perez R, Gorriz Gomez E, Pulido-Duque JM, Argiles Vives JM, Pardo Moreno MD, Maynar Moliner M. [Wallstent endoprostheses implanted by fluoroscopic guidance in the palliative treatment of malignant esophageal obstructions and esophago-tracheal fistulas] Nutr Hosp. 1997;12:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carreira JM, Gorriz E, Reyes R, Argiles JM, Pulido JM, Pardo MD, Maynar M. [Treatment of dysphagia of malignant origin with the endoprosthesis of Strecker] Med Clin (Barc) 1998;110:727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]