Abstract

In this paper, we demonstrate for the first time that insulative dielectrophoresis can induce size-dependent trajectories of DNA macromolecules. We experimentally use λ (48.5 kbp) and T4GT7 (165.6 kbp) DNA molecules flowing continuously around a sharp corner inside fluidic channels with a depth of 0.4 μm. Numerical simulation of the electrokinetic force distribution inside the channels is in qualitative agreement with our experimentally observed trajectories. We discuss a possible physical mechanism for the DNA polarization and dielectrophoresis inside confining channels, based on the observed dielectrophoresis responses due to different DNA sizes and various electric fields applied between the inlet and the outlet. The proposed physical mechanism indicates that further extensive investigations, both theoretically and experimentally, would be very useful to better elucidate the forces involved at DNA dielectrophoresis. When applied for size-based sorting of DNA molecules, our sorting method offers two major advantages compared to earlier attempts with insulative dielectrophoresis: Its continuous operation allows for high-throughput analysis, and it only requires electric field strengths as low as ∼10 V∕cm.

INTRODUCTION

Dielectrophoresis has been frequently applied in various lab-on-a-chip devices, particularly because they can be actuated using both ac and dc voltages, and when applied for sorting small particles, they do not require the particles to be electrically charged as in electrophoresis.1, 2 Basically, there are only two key factors needed in actuating the dielectrophoresis: The particles to be manipulated need to be electrically polarizable, and there must exist a gradient of electric field around those particles. However, there exists one disadvantage of dielectrophoresis: This force is proportional to the volume of the particles, which means it is generally impractical to use it for objects with characteristic lengths smaller than 1 μm (such as DNA molecules). This is particularly relevant for one type of realizations of dielectrophoresis, i.e., the so-called insulative dielectrophoresis,3 where actuation of dielectrophoresis relies solely on external electrodes located outside the microfluidic∕nanofluidic channels (as opposed to internally microfabricated electrodes usually used in conventional dielectrophoresis in lab-on-a-chip) such that the large distance between the electrodes implies a relatively weaker electric field strength in the channels.

To circumvent this problem, insulative structures could be fabricated inside the channels,3 such that sufficiently strong electric field gradients occur near these structures. This scheme has been used on DNA sorting and manipulation, starting with the proposition made by Ajdari et al.,4 then realized in the form of DNA trapping by Chou et al.,5 and eventually applied in DNA sorting by Regtmeier et al.6 However, this scheme relies on trapping (rather than directly sorting) the DNA molecules, and hence cannot be operated continuously and is prohibited from achieving higher throughput.7

In this paper, we demonstrate for the first time that insulative dielectrophoresis could also be used to induce size-dependent trajectories of individual DNA molecules that are flowing continuously. We experimentally use λ (48.5 kbp) and T4GT7 (165.6 kbp) DNA molecules flowing continuously inside our 0.4-μm-deep fluidic channels. The electric field gradient, required for the dielectrophoresis actuation, is actuated using a sharp corner at our U-turn-shaped channel. Our numerical simulations elucidate how the geometry of the U-turn allows insulative dielectrophoretic forces to induce the DNA sorting. Similar channel geometries, with sharp corners, have been published before, but they have been applied only for inducing size-dependent trajectories of objects with larger characteristic lengths, such as polystyrene beads8 and biological cells.9 Our results show that similar geometries and schemes can also be applicable to DNA molecules, and generally to any other electrically polarizable biological molecules.

METHODS

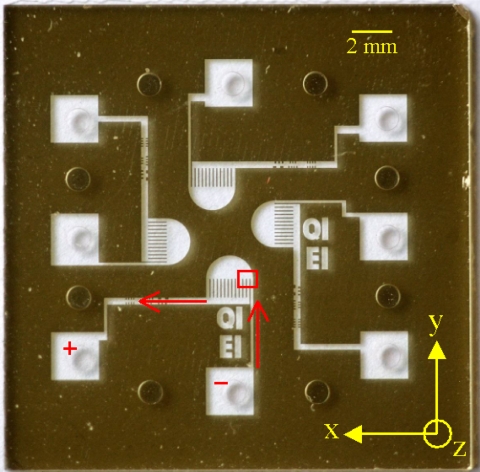

The microphotograph and schematic of our fluidic channel is shown in Fig. 1, where the red arrows indicate the general direction of the DNA motion and white parts indicate the channels. The solution of DNA molecules passes through a 100-μm-wide straight “inlet channel,” before entering a “semicircular chamber” with a radius of 1 mm. Twelve 100-μm-wide “suboutlet channels” collect the fluid out of the chamber into a 273-μm-wide main outlet (in a later version of the device design, each suboutlet channel could be connected to separate subsequent channels). Note that in this paper these suboutlet channels are not yet useful to collect the sorted molecules (because the sorted molecules are still collected by the same suboutlet channels); however, the main goal of this paper is to demonstrate a proof-of-principle that we can induce size-dependent trajectories at the sharp corner. Negative and positive voltages are applied to the inlet and the outlet ports, respectively, in order to induce electrophoretic motion of the DNA molecules. Our fluidic channels have a channel depth of 0.4 μm and were fabricated in our own facilities using glass-to-glass anodic bonding.10 Two types of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) molecules are employed in our experiments, λ-DNA (contour length=48.5 kbp; purchased from Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and T4GT7-DNA (contour length=165.6 kbp; purchased from Wako Nippon Gene, Osaka, Japan). In an unconfined solution, the radius of gyration of the λ-DNA and the T4GT7-DNA are 0.74 μm and 1.37 μm, respectively.11 We choose the channel depth so that it is sufficiently shallow (i.e., less than the molecules’ radius of gyrations, such that the molecules are confined and squeezed by the upper and lower walls inside the channels) to allow for single molecule detection, while also sufficiently deep such that the electrophoretic forces could still pull the molecules pass the entropy barrier at the entrance of the inlet channel.

Figure 1.

A photograph of the fluidic channels (courtesy of Hans Stakelbeek∕FMAX). Four of similar channels are fabricated in the same chip. The red arrows indicate the flow direction, the red rectangle shows the region of observation, while the ”+” and ”−” marks represent the polarities of the dc electrodes in the experiment. A Cartesian coordinate system, used in the analysis, is also shown. The scale bar represents 2 mm.

All of the DNA molecules were stained with a 1:8 (dye:basepair) ratio using a YOYO-1 dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), which has excitation and emission maxima at 491 nm and 509 nm, respectively. All DNA-dye solutions were diluted with Milli-Q purified water (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and then 2% (v∕v) 2-mercaptoethanol was added to suppress photobleaching. The motion of individual DNA molecules inside the fluidic channels was driven using various electric fields generated by a voltage source (Wavetek 143, Willtek, Ismaning, Germany) and then observed with a “TCS SP2–DM RXA” Leica Microsystems (Wetzlar, Germany) microscope. We used a 20× objective lens (NA=0.4), which provides a depth of field of ∼3 μm, and used an N21 optical filter set from Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) with a xenon lamp. The fluorescence signal was measured using an Orca-ER Hamamatsu (Hamamatsu City, Japan) charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (pixel size of 6.45 μm), with an exposure time of 100 ms and 4×4 pixels binning. The microscope is used in wide-field mode as opposed to the confocal mode.

Previously we have analyzed the electro-osmotic and electrophoretic forces inside the branched U-turn fluidic channels and found that the highest electric field gradient, which could enable changes on the trajectories of the DNA molecules through dielectrophoretic forces, is located where the “inlet channel” intersects with the “semicircular chamber” and the first and second sub-outlet channels.12 We therefore focus our observations in this study on the same region, which is also shown as the red rectangle in Fig. 1.

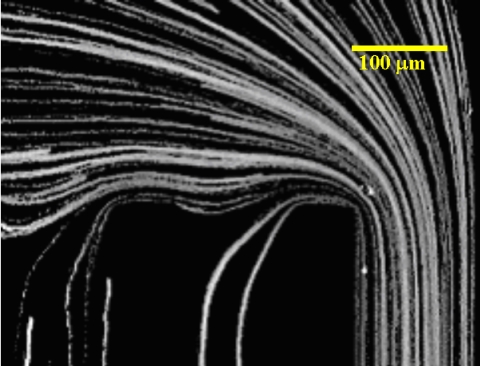

In each of the original fluorescent images, individual DNA molecules could be seen flowing continuously in the channel. To obtain the trajectory information, we simply add up these original images in each set of measurement into a “trajectory image.” A typical trajectory image is shown in Fig. 2 (this particular example is of T4GT7-DNA molecules driven by a dc electric field of V=15.3 V).

Figure 2.

A typical example of a trajectory image, showing the trajectories of DNA molecules flowing at the region of observation; this is obtained simply by adding up original fluorescent images in each measurement set. The scale bar represents 100 μm.

It is very difficult to compare and quantitatively analyze several trajectory images using only human visual inspection. Therefore, we perform some image analysis steps on the measured fluorescent images using our image processing toolbox DIPimage.13 First, we create a background image by averaging all original fluorescent images in one particular measurement. The background image, Imagebg, can be expressed mathematically as

| (1) |

where n is the number of images in the analyzed measurement data (n≈1000). The background image is then subtracted from each of the original images in that measurement in order to remove unwanted signals such as autofluorescence from the channel walls and static objects in the channels. Afterwards, DNA molecules in each resulting images are segmented from the background using a fixed threshold algorithm.14 The analysis is only done in a region of interest (ROI), which is defined as a rectangle around a single DNA molecule of interest, where the position of the molecule is determined by measuring the center of gravity across the ROI. In order to track the moving molecule, the ROI is also moved along with the molecule. This is done by using the measured molecule’s center of gravity to specify the center of the moved ROI. Individual trajectories are then determined by tracking the molecules through the image sequence in the measured data.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

For our analysis, we need to consider all the electrokinetic forces involved in the transport of the DNA molecules. As the electric field is applied, the negatively charged DNA molecules are driven from the negative electrode toward the positive electrode by electrophoresis, while the liquid surrounding the DNA and filling the channels flows in the opposite direction due to electro-osmosis (note that both the electrophoretic and electro-osmotic motions are always identical, and hence parallel, to the electric field lines, such that they cannot, by themselves, induce a net motion toward or away from the electric field gradients at the sharp corner). On top of that, the combination between DNA molecules and their surrounding counterions can be polarized and, where an electric field gradient exists, the DNA molecule can be attracted to the region with the highest electric field gradient because of dielectrophoresis.5 Hence electrophoresis and electro-osmosis only determine the velocity and general pathline of the DNA molecules, while dielectrophoresis can alter the details of the trajectories of the DNA molecules (toward or away from the sharp corner). The total velocity field across the channels is the sum of the electro-osmotic, electrophoretic, and dielectrophoretic velocity fields,

| (2) |

with μEK as the electro-osmotic plus electrophoretic mobility and μDEP as the dielectrophoretic mobility.3

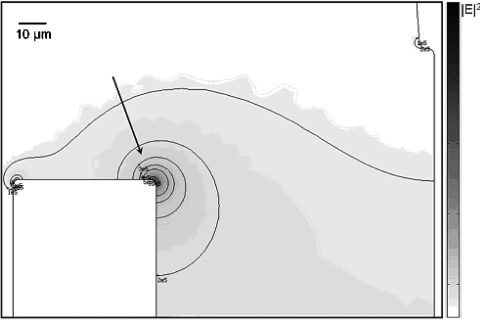

We have performed a two-dimensional finite-element numerical computation of ∣E∣2 through the channels, using the Electrostatics Module in Comsol Multiphysics 3.3 (Comsol, Burlington, MA, USA). The computation was performed for the whole device (shown in Fig. 1), but we specifically only show the results at the region of experimental observation (shown in Fig. 3) because the significant electric field gradients (induced by electrodes in inlet and outlet) only occur here. The mesh size is made uniform and sufficiently small throughout all the channels, such that the ∣E∣2 values do not change anymore when the mesh is refined further. For the boundary conditions, we assume total insulation in all the channel walls and apply negative and grounded voltages to the inlet and outlet ports, respectively (note that we only simulate normalized distribution of the electric field, which is not influenced by the actual voltage differences applied in the simulation). Moreover, because infinitely sharp corners cannot be practically achieved during the fabrication, we use rounded channel corners in the simulation. We observed that this does not significantly change the qualitative distribution of ∣E∣2 in the whole device, except very near the corner indicated by the arrow in Fig. 3, where sharp corners would result in a nonrealistic singularity at that corner, while rounded corners result in a more smooth distribution of ∣E∣2. From Fig. 3 we can also see that the region where we have a nonzero gradient of ∣E∣2, i.e., where dielectrophoresis could alter the trajectories of DNA molecules [see Eq. 2], is around the corner indicated by the arrow.

Figure 3.

A two-dimensional numerical simulation of the electric field squared, ∣E∣2; the simulation was performed on the whole device shown in Fig. 1, but here we specifically show only the region of our experimental observation, i.e., at the end of the “inlet channel,” because the significant electric field gradients (induced by electrodes in inlet and outlet) only occur here. The color bar has maximum and minimum values of 2.233×106 V2 and 1.011×10−8 V2, respectively. Several iso-level contours of ∣E∣2 are also shown (for ∣E∣2 equal to 1×106, 0.5×106, 0.4×106, 0.3×106, 0.2×106, and 0.1×106 V2) as a quantitative visual aid. The dark region at one of the wall corners, indicated by the arrow, shows the location with the highest value of ∣E∣2 throughout the branched U-turn nanofluidic channel. The region with the nonzero gradient of ∣E∣2 is around that corner. The scale bar represents 10 μm.

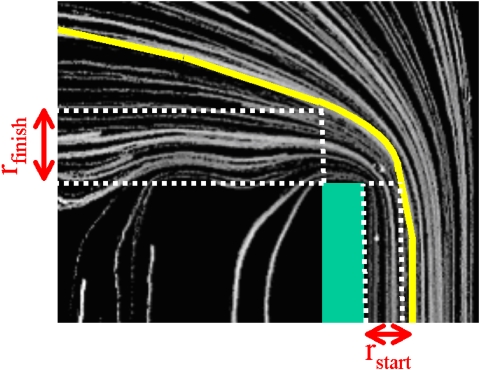

The next step in the analysis is to quantitatively compare and analyze each trajectory in all measurements and for that purpose we define two parameters as shown in Fig. 4, in which the yellow line represents an exemplary DNA trajectory employed to show how to measure the parameters, while the green box represents the walls with the sharp corner. First we measure the “start distance,” rstart, as the absolute distance along the x axis from the first corner in the walls. Then we also measure the “finish distance,” rfinish, as the absolute distance along the y axis from the second corner in the same walls. These distances are then calculated using a conversion factor of 1 pixel width=1.29 μm (taking into account the 4×4 pixels binning and the 20× lens we use in the experiments; this is also confirmed experimentally by using the known width of the inlet channel).

Figure 4.

The parameters used in the analysis are the “start distance,” rstart, and the “finish distance,” rfinish, measured from the corners in the walls. In this figure, we show how to determine these parameters for an exemplary trajectory, highlighted with the yellow line. The green box represents the wall with the sharp corner.

The electric field applied during the measurements can be expressed as V=A sin(2π ft)+B, where f and A are the frequency and amplitude of the ac signal, respectively, while B is the dc offset superimposed on the ac signal. The total contour length of the channels between the inlet and outlet ports, where the electric fields are applied, is approximately 2 cm. Table 1 shows the parameters chosen for the experiments, resulting in ten data sets. The plots in Fig. 5 summarize the results of the experiments. In order to test the repeatability of our observations, we perform a second set of experiments more than one month after the first set of experiments, using different chips. In the plots shown in Fig. 5 we therefore use the notations “1” and “2” on the data sets, which indicate the first and second set of experiments, respectively.

Table 1.

List of parameter choices in the experiments, along with the respective data set names and colors used in the plots.

| DNA molecules | Electric field:A=0 Vf=0 Hz B=7.5 V | Electric field:A=0 Vf=0 Hz B=15.3 V | Electric field:A=14 Vf=1 HzB=15.3 V | Electric field:A=14 Vf=1 kHzB=15.3 V | Electric field:A=14 Vf=1 MHzB=15.3 V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ (48.5 kbp) | Data set A (green) | Data set B (green) | Data set C (green) | Data set D (green) | Data set E (green) |

| T4GT7 (165.6 kbp) | Data set F (red) | Data set G (red) | Data set H (red) | Data set I (red) | Data set J (red) |

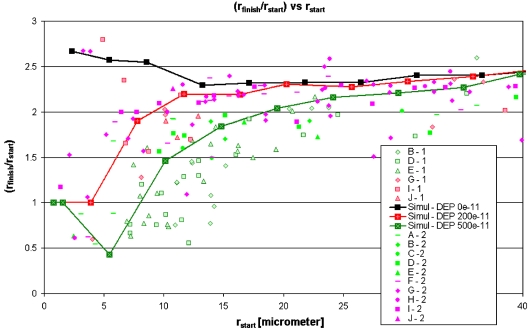

Figure 5.

The plot of (rfinish∕rstart) vs rstart along with the simulated trajectories for all rstart values.

In Fig. 5 we plot (rfinish∕rstart) versus rstart for all data sets. If size-dependent DNA trajectories occur, then λ-DNA and T4GT7-DNA will systematically have different trajectories, and consequently have different values of (rfinish∕rstart), even though they start at the same position in the inlet and have the same value of rstart. Let us now compare the green markers (data sets A-E, i.e., the λ-DNA trajectories) and the red markers (data sets F-J, i.e., the T4GT7-DNA trajectories) in Fig. 5. For rstart<∼25 μm, the green markers consistently have (rfinish∕rstart) values lower than the red markers. Physically this indicates that we can sort a mix of λ-DNA and T4GT7-DNA in 0.4-μm-deep channels for rstart<∼25 μm, because for the same values of rstart their trajectories end up with different (rfinish∕rstart). Note that in order to properly analyze the quality of the trajectory separation, the distribution of green and red data points shown in Fig. 5 must be compared for each value of rstart. For every value of rstart below ∼25 μm, a clear classification can always be performed to separate between the green and red data points.

Using the same numerical computation as was used to plot Fig. 3, we also simulate the electrokinetic DNA trajectories. In the simulation, we adjust the ratio of dielectrophoretic mobility, μDEP, and electrokinetic mobility (i.e., the electro-osmotic plus electrophoretic), μEK, as defined in Eq. 2. The simulation results are also plotted in Fig. 5, for ρμ=(μDEP∕μEK) equal to zero (i.e., when there is no dielectrophoresis effect in the system; shown as black boxes with line), ρμ=200×10−11 m kg s−7 A−3 (shown as red boxes with line), and ρμ=500×10−11 m kg s−7 A−3 (shown as green boxes with line); the latter two simulation cases represent positive dielectrophoresis of DNA molecules (where the DNA electrokinetic trajectories are shifted toward the highest electric field gradient indicated in Fig. 3), in agreement with the previously published insulative dielectrophoresis results.5, 6

Comparison between the simulation and experimental data in Fig. 5 shows that the simulation of ρμ=200×10−11 m kg s−7 A−3 matches the data sets with red markers, while the simulation of ρμ=500×10−11 m kg s−7 A−3 matches the data sets with green markers. This shows that the trajectories of the larger DNA (T4GT7-DNA) are attracted by dielectrophoresis toward the walls corner less strongly than the trajectories of the smaller DNA (λ-DNA). These observations were not expected because Chou et al.5 reported that, in contrast to our observations, dielectrophoretic effects on DNA molecules increase when the DNA size is increased. In Sec. IV we will discuss this in more detail, and we will describe a possible physical mechanism behind the observed phenomena.

Above we have shown that insulative dielectrophoresis can induce size-dependent DNA trajectories, particularly for rstart<∼25 μm, i.e., for trajectories that are close enough to the highest grad (∣E∣2) value in the channel. For rstart>∼25 μm, no size-dependent trajectories can effectively be induced because the trajectories are too far away from the corners in the channel walls, hence no significant dielectrophoresis effect exists. We should note, however, that the dimensions and configurations of the channels in our branched U-turn fluidic channels are not yet optimized for an actual sorting of the DNA molecules. To do DNA sorting effectively, the following geometry modification of the channels could be done: (1) Connect a three-branch channel prior to the inlet channel, as in cytometry devices,15 to allow sheath flows to control the rstart of the DNA molecules coming to the inlet channel, and (2) connect several identical sharp corners in series (i.e., after a crude-separation corner, each separated trajectories can be split into two channels and then directed to fine-separation corners), so that the sorting capability can be amplified to obtain a higher separation resolution. This would be particularly useful if we need to sort a mix of more than two types of DNA molecules, or when we have smaller size differences between the different types of DNA molecules.

In order to see the effect of modifying the applied electric fields, we can compare the trends of data sets in each color of the markers (i.e., comparison between data sets A-E among the green markers, and between data sets F-J among the red markers). The plots in Fig. 5 show that there is no clear distinction between the trends of data sets within each set of marker color in the data sets. In other words, we do not observe any significant effect by changing the applied electric fields (between the inlet and the outlet) in our experiment. Note that, because the ac fields in our experiments only have a frequency of 1 Hz, 1 kHz, or 1 MHz, further investigations could also be done with higher frequencies because the dielectrophoresis effect has been reported to increase when the ac frequency is increased.5 We also need to note that there is a difference between our experiments and the earlier published experiments: The submicrometer-deep channels in our setup imply that the DNA macromolecules experience stronger influences from the upper and lower walls, compared to the case of Chou et al.5 and Regtmeier et al.6 where the channel depths are 1.25 and 6 μm, respectively. In the following section, we will discuss this difference and discuss a possible physical mechanism of DNA polarization and dielectrophoresis in confining channels, which may answer the following two questions: (1) Why are the dielectrophoresis effects in our experiments not significantly affected by changing the electric fields applied between the inlet and the outlet? (2) Why (as mentioned earlier) do the dielectrophoresis effects in our experiments increase as the DNA size decreases, opposite of the findings reported by Chou et al.5 and Regtmeier et al.?6

PHYSICAL MECHANISM OF CONFINED DNA DIELECTROPHORESIS

Despite the published successful demonstrations of insulative dielectrophoresis on DNA molecules, the physical mechanisms involved in the phenomena remain unclear.5, 6 When Pohl1 first reported on dielectrophoresis, his proposed model depicted particles being polarized under an external electric field, such that the charge distribution within each of the polarized particles is rearranged into an electrical dipole. This model was successfully used to explain the insulative dielectrophoresis of spherical beads3, 8 and biological cells.9 In particular, because both spherical beads and biological cells are nonconducting objects, the so-called “Clausius-Mossotti factor” always has a value of (−0.5), and this negative value can well explain why only negative dielectrophoresis occurs when those objects move passing an insulative corner. However, the model cannot be applied on DNA molecules because the charge distribution of a DNA molecule is fixed on its backbone (which comprises sugar molecules and phosphate groups, with the excess negative charges located in each phosphate group) and cannot be redistributed within the DNA molecule itself. In a liquid solution, however, the backbone attracts counterions. Hence when an electric field is applied, the field affects not only the DNA molecule but also the surrounding counterions. A model of DNA dielectrophoresis was therefore proposed16, 17 where the induced electrical dipole consists of both the DNA molecule and the counterions, such that the DNA polarization is actually realized by the diffusion of the counterions around the DNA molecule, which is allowed by the hydrodynamically free-draining nature of DNA molecules when contained in a salt solution or in a confining channel.18

Chou et al.5 refer to this model when they publish their experiments. To improve the model quantitatively, they varied several parameters in their experiments. First, they observed that the dielectrophoresis effect increases as the ac amplitude (and consequently, also the electric field gradient near their insulative structures) increases; this, however, is already predicted by the general dielectrophoresis theory.1 Second, they reported that in general the dielectrophoresis effect increases as the ac frequency increases, but in some cases it decreases again at a certain frequency. They assign this decrease to the dispersion (i.e., the frequency-dependent property) of the dielectric response of a DNA molecule and its surrounding counterions. They then proposed a model, in which a DNA and its counterions can be portrayed as a combination of a single capacitor C, i.e., the (charged, but insulative) DNA backbone, and a single resistor R, i.e., the diffusion transport of the counterions along (but not through) the molecule, such that the dispersion relaxation time can be analyzed similarly like a relaxation time RC used in an electrical circuit. With this model, for a molecule where the extended length L is much longer than its persistence length P, and assuming that the unconfined molecule forms a blob with the mean separation between the molecule ends expressed as (2*L*P)1∕2, they provide an estimation of the relaxation time, T, as T=(L*P)∕D, where D is the diffusion coefficient of the counterions. However, this estimation was shown to consistently underestimate the experimentally observed value (obtained from the ac frequency where the dielectrophoresis effect starts to decrease) with a multiplication factor of ∼(1∕2). Moreover, this model does not take into account the free-draining nature of DNA molecules, in which the diffusion of the counterions through the DNA molecules may imply that a much more complex RC model is required. Third, they showed that the dielectrophoresis effect increases as the DNA size increases. They then discuss how to estimate the actual dielectrophoretic force experienced by a DNA molecule, which in general is expressed as F=α*∣E∣*grad(E), where α is the DNA polarizability. They proposed to estimate F by estimating the value of α with the equation (particularly for the case where L is much larger than P), where ε and ε0 are the relative permittivity of the solution and the permittivity of vacuum, respectively. Nevertheless, they did not use and test this estimation of α because they eventually determined F only experimentally by analyzing the distribution of the DNA concentration trapped at the insulative structures. Meanwhile, Regtmeier et al.6 focused more on the experimental demonstration of DNA trapping and sorting; they did not attempt to extend the model proposed by Chou et al.5 Interestingly, however, they reported that they were surprised by the good agreement between the measured values of F in their experiments and in the ones performed by Chou et al.,5 considering the differences in the liquid solution properties, DNA lengths, and ac frequency ranges. Moreover, even though they listed various values of α found in the literature, they remarked that a direct comparison between those values and their own observed values would seem questionable in view of the various measurement methods, liquid solution properties, and ac frequency ranges being used.

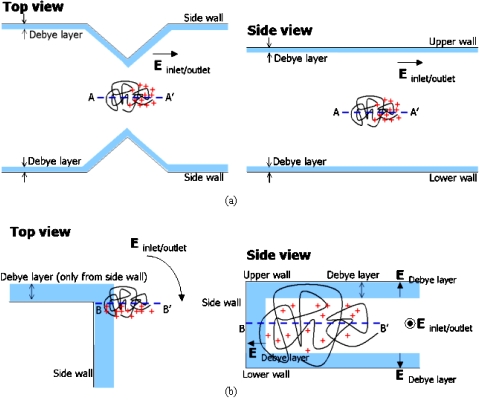

The DNA dielectrophoresis model used by Chou et al.5 considers only one type of electric field, i.e., the electric field applied between the inlet and the outlet. This was valid for the experiments by Chou et al.5 and Regtmeier et al.,6 where the DNA molecules can still form an unconfined blob and the effects from upper and lower walls can be assumed to be negligible. However, this may not be valid anymore for our case, where the channel depth (0.4 μm) is smaller than the radius of gyrations of λ-DNA (0.74 μm) and the T4GT7-DNA (1.37 μm), such that the upper and lower walls always squeeze the molecules. Hence, in our case, the DNA molecules may also be affected by another type of electric field, i.e., the electric field due to the Debye layers shielding the channel walls. Ajdari et al.4 have actually mentioned this issue, but they argued that the electric field induced by their upper and lower walls are negligible for their case because their proposed device’s channel depth is much larger than their calculated Debye layers thickness of ”only” ∼0.5 μm (in our case, this thickness is actually significant because it is in the same order as our channel depth). More recently,19, 20 experiments with submicrometer-deep channels have shown that there exists a significant transport of the counterions along the channel depth (i.e., along the z axis in Fig. 1), particularly when the thickness of the Debye layers at the upper and lower channel walls is in the same order as the channel depth. Related to this, Baldessari et al.21 noted that the electric field strengths in the Debye layers, which can be in the order of 105 V∕cm (assuming a zeta potential of the walls in the order of ∼100 mV and a Debye layer thickness in the order of ∼10 nm), is strong enough to induce DNA polarizations. Therefore, when a DNA molecule is co-located with the channel walls’ Debye layers, the electric fields at the Debye layers also affect the counterions surrounding a DNA molecule, such that the combination of DNA molecules and their surrounding counterions can be polarized perpendicular to the Debye layer, leading to DNA dielectrophoresis. As a comparison, Fig. 6 shows two schematic drawings (not to scale): (a) The physical model of an unconfined DNA molecule used by Chouet al.5 and (b) the physical model of a confined DNA molecule used for our case; the blue areas represent the Debye layers, while the red “+” marks represent the counterions.

Figure 6.

Schematic drawings (not to scale) of (a) the model used by Chou et al. (Ref. 5) and (b) the model used for our case. The blue areas represent the Debye layers. The red ”+” marks represent the counterions.

Let us now look at our experimental setup. The electric field applied between the inlet and the outlet have a strength of ∼10 V∕cm, with the highest field gradient located at the U-turn corner (see Fig. 3). Meanwhile, the electric field strengths in the Debye layers in our channels are in the order of ∼104 V∕cm (assuming the zeta potential of the walls of ∼100 mV and the thickness of the Debye layer of ∼100 nm, for the pH=7.8 buffer solution used in our DNA solution), where the location of the highest field gradient is again at the U-turn corner, particularly at the junctions between the Debye layer at the side wall and the Debye layers at the upper∕lower walls [see Fig. 6b, particularly the side view]. The total electric field strength experienced by a DNA molecule, when it is co-located with Debye layers, is then equal to the superposition of the two different electric field strengths mentioned above. Due to the large difference in the order of magnitude (∼10 and ∼104 V∕cm), the total electric field strength is then in the same order as the electric field strength due to the Debye layers: ∼104 V∕cm. Therefore, the DNA dielectrophoresis is mainly caused by the electric fields in the Debye layer, not the electric fields applied between the inlet and the outlet (note that, from the theory proposed by Pohl,1 dielectrophoresis can also occur at dc fields, which may be occurring in the Debye layers, where the electric potential varies from the wall’s zeta potential at “shear layer” very close to the walls to electrically neutral at the edge of the Debye layers). This means, once the DNA molecules enter the channels, the Debye layers at the upper∕lower walls perpetually polarize the DNA molecules and their surrounding counterions. Most importantly, this proposed physical mechanism can well explain our observation, in which the dielectrophoresis effect is not significantly affected when we changed the parameters (amplitude and frequency) of the applied electric field between the inlet and the outlet as listed in Table 1. This fact, that the insulative DNA dielectrophoresis seems to be independent of the electric fields applied between the inlet and the outlet, might raise some concerns to some readers. However, this fact is actually advantageous: The sorting method can simply be operated in a passive manner, without requiring complex manipulation of the electric fields frequencies between the inlet and the outlet. Meanwhile, the electric field amplitude, regardless whether it is a dc or ac field, is still very useful: Increasing the amplitude would also increase the electrophoretic velocities of the DNA molecules along their trajectories, allowing for higher throughput in the molecular sorting and analysis.

Meanwhile, when DNA molecules are located inside confining channels, in which the channel depth is much less than the DNA’s unconfined radius of gyration (as in our case), the de Gennes model predicts that the DNA conformation changes from a single unconfined blob into an extended chain of smaller blobs.22 The length of this extended chain, R, can then be expressed as R=L*[(w*P)∕h2]1∕3, where w is the DNA width and h is the channel depth. For our DNA molecules (Llambda=16 μm, LT4GT7=55 μm, w=2 nm, P=50 nm,h=0.4 μm), we obtain Rlambda=1.4 μm, RT4GT7=4.7 μm. In our analysis of DNA sorting, we compared the two types of DNA molecules for the same values of rstart, such that they occupy the same center of gravity when recorded in the fluorescence images. When a Lambda-DNA and a T4GT7-DNA have the same center of gravity, the different values of the extended chain length R means that they sample two different sizes of volume near the electric field gradients at the sharp corner in the channels. In particular, the T4GT7-DNA molecules (i.e., the larger one between the two types) also sample regions with weaker electric field gradient (i.e., regions further away from the corner), which are not sampled by the Lambda-DNA molecules. The dielectrophoresis is therefore rendered to be less effective on the larger DNA than on the smaller DNA, as was observed in our experiments.

The physical mechanism we proposed above may answer the two questions we mentioned in the end of the previous section. First, we have shown that the electric field strengths in the Debye layers at the channel walls are orders of magnitude stronger than the electric field strengths applied between the channel’s inlet and outlet. Hence, the DNA polarization is mainly caused by the electric fields in the Debye layers, such that the dielectrophoresis effects in our experiments are not significantly affected by changing the electric fields applied between the inlet and the outlet. Second, the confinement by our channels, which induce the free-draining property of the DNA, allows for free diffusion of the counterions through the DNA molecules, implying that the simple RC model proposed by Chou et al.5 is not sufficient anymore. In replacement, we proposed a new physical mechanism based on the statistical mechanics of the DNA molecules, showing that the larger molecules also sample regions with weaker electric field gradient, rendering the dielectrophoresis in our experiments to be less effective on the larger DNA than on the smaller DNA.

Please note that the proposed physical mechanism above is still far from being a full mathematical model. To achieve this, two alternative efforts can be performed: (1) More extensive experimental studies, with many more repetitions and many more changes in parameters, and (2) a comprehensive three-dimensional Brownian dynamic simulations as proposed by Baldessariet al.21 However, these would be beyond the scope of this paper, which is focused mainly on experimentally demonstrating size-dependent trajectories of DNA molecules due to insulative dielectrophoresis in submicrometer-deep channels. Meanwhile, the numerical calculation that we performed (see Fig. 3) is also not a full physical model of the observed experimental data because it is actually only a phenomenological model probing the ratio between the effects of different electrokinetic forces in our setup. However, the calculation using Eq. 2 is a very simple and useful tool to study the different dielectrophoresis behaviors between different samples, and more importantly it allows us to determine the apparent dielectrophoretic mobilities of all the samples; note that Cummings et al.3 also used a similar numerical method in analyzing the effects of insulative dielectrophoresis on various spherical beads’ trajectories.

In the discussions above, we have assumed that the observed phenomena are solely due to dielectrophoretic forces. This assumption was used because the other forces cannot explain the data. We will now provide a list of those other forces. First are the electrophoretic and electro-osmotic forces. As was discussed in our previous publication, both these forces cannot induce motions toward or away from the corner in the channels,12 even though they may induce different DNA mobilities in extremely shallow channels.23 Actually, in our numerical calculation (see Fig. 3), we have already taken into account these two forces, and show that they do not induce sorting because their induced motion is always parallel to the electric field lines, independent of the electric field gradient. Second, there may be the hydrodynamic forces, particularly related to the drag of the molecules and the hydrodynamic filtration of them. Regarding the drag, the DNA molecules in a confining channel are free-draining such that the drag force is proportional to the DNA length, and this cannot induce motion toward or away from the corner in the channels. As for the hydrodynamic filtration,24 this method also fractionates two particles with different sizes passing around a corner, such that the smaller particle tends to stay closer to the wall (and consequently, tends to make a sharper bend) than the bigger particle due to the steric interactions between the particles and the channel walls. However, the two different types of particles sorted by this method have the same distance between the channel wall and the particles’ nearest edge, implying that they already have different distances between the channel wall and the particles’ center of gravity, even before they pass the corner. Because in our image analysis we only compare different trajectories for the same rstart (i.e., the same distances between the channel wall and the particles’ center of gravity), we have ensured that our observed size-dependent trajectories are not due to hydrodynamic filtration. Third, there may also exist the inertia forces on the DNA molecules, particularly if they turn around the sharp corner with high velocities. However, in channels with a low Reynolds number (in our case: in the order of 10−3), these inertia forces become negligibly small, such that particles and molecules can turn around sharp corners without exhibiting a significant momentum.12 Therefore, after considering all the forces above, it is valid for us to assume that the observed size-dependent trajectories in our experiments are solely due to dielectrophoresis. Nevertheless, the discussion above highlights how complex the physical system in the experiment is, such that the list of forces we provided above might be not entirely complete. If this occurs, further investigations, both theoretically and experimentally, would be very useful to elucidate and pinpoint the actual force that causes the observed phenomena. Moreover, these investigations would also be very useful to better elucidate the complete physical mechanisms involved at DNA dielectrophoresis.

CONCLUSION

In this paper, we demonstrate for the first time that insulative dielectrophoresis can be applied to induce size-dependent trajectories of DNA molecules. In our experiments, we use λ (48.5 kbp) and T4GT7 (165.6 kbp) DNA molecules flowing continuously inside our 0.4-μm-deep channels. Meanwhile, numerical simulations of the electrokinetic force distribution in our channels are in qualitative agreement with our experimentally observed DNA trajectories. Also, we discuss a possible physical mechanism of DNA polarization and dielectrophoresis inside confining channels, which may explain (1) why the dielectrophoresis effects in our experiments are not significantly affected by changing the electric fields applied between the inlet and the outlet, and (2) why the dielectrophoresis effects in our experiments increase as the DNA size decreases, the opposite of earlier published results. We expect that our observed results, along with our proposed physical mechanism, would stimulate further scientifically fundamental investigations on the dielectrophoresis of DNA molecules in fluidic channels. Such investigations would also help to pinpoint which forces actually cause the observed phenomena; in particular, the role of counterions should be clarified further to allow for a full modeling of the DNA dielectrophoresis. The same investigations may also help to explain, for instance, why only positive dielectrophoresis of DNA has been reported so far (note that the notion of the Clausius-Mossotti factor is inapplicable, and consequently cannot be used to explain the switch between positive and negative dielectrophoresis for the case of DNA molecules), whereas both positive and negative dielectrophoresis have been reported (and well explained theoretically by the Clausius-Mossotti factor) for beads and cells. Moreover, it would also be interesting and useful to investigate in detail whether the reported “spontaneous stretching of DNA in a two-dimensional nanoslit”25 could also be explained by the physical mechanism we propose in this paper.

When applied for size-dependent sorting of DNA molecules, our method provides two major advantages to previously published results5, 6: (1) Our method allows for continuous operation, which in turn could open possibilities for high-throughput molecular analysis, and (2) our method only needs electric field strengths as low as ∼10 V∕cm (as opposed to 200–1000 V∕cm used by other authors). We therefore expect that this paper would stimulate new methods in continuous size-based sorting of DNA molecules inside fluidic channels. Even though we only use DNA molecules in this study, the concept of continuous sorting should also be valid for any other polarizable biological molecules that can be manipulated with dielectrophoresis, and can furthermore be extended to perform free-flow continuous dielectrophoretic separation on cells and other polarizable microparticles.26

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Wim van Oel and Guus L. Lung for technical assistance in preparing the experimental setup, Hans Stakelbeek (FMAX) for the photograph of our chip used in Fig. 1, Professor Cees Dekker, Professor Hans J. Tanke, Professor Albert van den Berg, and Professor Menno W. J. Prins for their critical comments, and the Dutch Foundation for Fundamental Studies of Matter (FOM) for partial financial support.

References

- Pohl H. A., Dielectrophoresis—The Behaviour of Neutral Matter in Nonuniform Electric Field (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E. B. and Singh A. K., Anal. Chem. 10.1021/ac0340612 75, 4724 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdari A. and Prost J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4468 88, 4468 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C.-F., Tegenfeldt J. O., Bakajin O., Chan S. Y., Cox E. C., Darnton D. T., and Austin R. H., Biophys. J. 83, 2170 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regtmeier J., Duong T. T., Eichhorn R., Anselmetti D., and Ros A., Anal. Chem. 79, 3925 (2007). 10.1021/ac062431r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijkel J. C. and van den Berg A., Lab Chip 6, 19 (2006). 10.1039/b516903h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. H., Xuan X., Kang Y., and Li D., J. Appl. Phys. 10.1063/1.2180430 99, 064702 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Li D., Kalams S. A., and Eid J. E., Biomed. Microdevices 10, 243 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutchoukov V. G., Laugere F., van der Vlist W., Pakula L., Garini Y., and Bossche A., Sens. Actuators, A 114, 521 (2004). 10.1016/j.sna.2003.12.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. C., Zohar Y., and Lee Y.-K, Proceedings of MEMS 2006, 19th IEEE Conference on Micro Electrical Mechanical Systems, Istanbul, 2006. (unpublished), pp. 438–441.

- Parikesit G. O. F., Markesteijn A. P., Kutchoukov V. G., Piciu V. G., Bossche A., Westerweel J., Garini Y., and Young I. T., Lab Chip 10.1039/b505493a 5, 1067 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L. C. L.uengo, L. J. van Vliet, B. Rieger, and M. van Ginkel, “DIPimage: A scientific image processing toolbox for Matlab,” Delft University of Technology, 1999, http://www.qi.tnw.tudelft.nl/DIPlib/.

- Young I. T., Gerbrands J. J., and van Vliet L. J., The Digital Signal Processing Handbook (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1998), Chap. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., El-Ali J., Engelund M., Gotsaed T., Perch-Nielsen I. R., Mogensen K. B., Snakenborg D., Kutter J. P., and Wolff A., Lab Chip 10.1039/b400663a 4, 372 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porschke D., Biophys. Chem. 10.1016/S0301-4622(97)00060-4 66, 241 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell D. J., Ermolina I., Morgan H., Milner J., and Feldman Y., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1493, 151 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viovy J. -L., Rev. Mod. Phys. 10.1103/RevModPhys.72.813 72, 813 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennathur S. and Santiago J. G., Anal. Chem. 10.1021/ac0508346 77, 6782 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennathur S., Baldessari F., and Santiago J. G., Anal. Chem. 79, 8316 (2007). 10.1021/ac0710580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessari F. and Santiago J. G., J. Nanobiotechnol. 4, 12 (2006). 10.1186/1477-3155-4-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner W., Morton K. J., Riehn R., Wang Y. M., Yu Z., Rosen M., Sturm J. C., Chou S. Y., Frey E., and Austin R. H., Phys. Rev. Lett. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.196101 94, 196101 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salieb-Beugelaar G., Teapal J., van Nieuwkasteele J., Wijnperle D., Tegenfeldt J. O., Eijkel J. C. T., and van den Berg A., “DNA movement in sub-20 nm nanoslits,” Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences (MicroTAS), Paris, 2007. (unpublished), pp. 1201–1203.

- Yamada M. and Seki M., Anal. Chem. 10.1021/ac0520083 78, 1357 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan M., Moench I., and Schwille P., Nano Lett. 10.1021/nl0701861 7, 1270 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikesit G. O. F., Markesteijn A. P., Westerweel J., Young I. T., and Garini Y., “Free-Flow Dielectrophoresis—A Numerical Study,” Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences (MicroTAS), Paris, 2007. (unpublished).