Abstract

Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young-type 3 (MODY-3) has been linked to mutations in the transcription factor hepatic nuclear factor (HNF)-1α, resulting in deficiency in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. In INS-1 cells overexpressing doxycycline-inducible HNF-1α dominant-negative (DN-) gene mutations, and islets from Hnf-1α knock-out mice, insulin secretion was impaired in response to glucose (15 mm) and other nutrient secretagogues. Decreased rates of insulin secretion in response to glutamine plus leucine and to methyl pyruvate, but not potassium depolarization, indicate defects specific to mitochondrial metabolism. To identify the biochemical mechanisms responsible for impaired insulin secretion, we used 31P NMR measured mitochondrial ATP synthesis (distinct from glycolytic ATP synthesis) together with oxygen consumption measurements to determine the efficiency of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Mitochondrial uncoupling was significantly higher in DN-HNF-1α cells, such that rates of ATP synthesis were decreased by approximately one-half in response to the secretagogues glucose, glutamine plus leucine, or pyruvate. In addition to closure of the ATP-sensitive K+ channels with mitochondrial ATP synthesis, mitochondrial production of second messengers through increased anaplerotic flux has been shown to be critical for coupling metabolism to insulin secretion. 13C-Isotopomer analysis and tandem mass spectrometry measurement of Krebs cycle intermediates revealed a negative impact of DN-HNF-1α and Hnf-1α knock-out on mitochondrial second messenger production with glucose but not amino acids. Taken together, these results indicate that, in addition to reduced glycolytic flux, uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation contributes to impaired nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion with either mutations or loss of HNF-1α.

Mutations in the transcription factor hepatic nuclear factor (HNF)2-1α in pancreatic β-cells are responsible for impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in patients with Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young-type 3 (MODY-3) (1–5). Of the numerous mutations in the HNF-1α gene associated with MODY-3, all of which negatively affect DNA binding and/or transactivation (6), the p291fsinsC frameshift mutation is the most common (7). This study also employed the dominant-negative SM6 construct that displays a very similar phenotype to p291fsinsC, both in cell lines and when expressed in the β-cells of transgenic mice (7–10). Studies of rat insulinoma INS-1 cells engineered with doxycycline-inducible expression of these DN-HNF-1α genes have shown that its expression impacts the mRNA and protein levels of several gene products integral to glycolytic and mitochondrial energy production (7, 8). Specifically, expression of the GLUT2 transporter, aldolase B, and L-type pyruvate kinase is decreased in these cells (7, 8), as well as in islets from mice expressing the DN-HNF-1α (9) or loss of Hnf-1α (5). Mitochondrial targets identified in the dominant-negative mutations in the HNF-1α cell lines include decreased expression of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 subunit and increased expression of UPC2 (7, 8), either of which could negatively affect mitochondrial energy production. The impaired responsiveness of these cells to glucose may be explained in part by these changes in glucose metabolism. However, it is uncertain whether the impaired GSIS can be attributed primarily to changes in glycolysis, or whether mitochondrial dysfunction is also a contributor. The products of mitochondrial metabolism are integral to fuel-stimulated insulin secretion, with the ATP/ADP ratio as the primary messenger, and putative secondary messengers that act to facilitate either the transfer of mitochondrial reducing equivalents to generate cytosolic NADPH (i.e. citrate, malate) or lipid synthesis (citrate). MacDonald et al. (11) provide a recent review of these and other mitochondria-derived second messengers and potential mechanisms whereby they may facilitate insulin secretion.

To evaluate the functional consequences of these changes in gene expression on the coupling of glucose and amino acid metabolism with insulin secretion and mitochondrial function, we combined metabolomic measurements and isotopic flux measurements of mitochondrial metabolism in INS-1 cells with dox-inducible expression of these dominant-negative mutations of HNF-1α and the nontreated cells as controls. Substrate input into the Krebs cycle by acetyl-CoA and anaplerotic pathways were determined using a 13C-isotopomer approach (12–14). In addition to quantifying PDH flux, this method also provides quantitative measures of flux through two significant pathways of anaplerosis in the β-cell, pyruvate carboxylase (PC), and entry at the level of succinate or α-ketoglutarate. Using this approach, we have previously established that fuel-stimulated insulin secretion strongly correlates with pyruvate cycling mediated by PC flux and cytosolic and/or mitochondrial malic enzyme flux (13, 14). These pathway measurements were augmented by high pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric (LC/MS/MS) measured changes in substrate concentration in response to high (15 mm) glucose or the combination of basal (3 mm) glucose with glutamine and leucine. We complemented these substrate flux measurements with 31P NMR measured rates of ATP synthesis (15), combined with fluorometrically measured rates of oxygen consumption (16), to assess the efficiency of mitochondrial ATP production.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

INS-1 cells (DN-HNF-1α) engineered with expression of the dominant-negative mutations of HNF-1α under control of the dox-dependent transcriptional activator were used in these studies (7, 8). The effects of the HNF-1α mutations were evaluated by comparison of cells exposed to dox with the same cells that are not exposed to dox and therefore do not express the DN-HNF-1α gene. INS-1 cells were cultivated as monolayers in RPMI 1640 medium, pH 7.4, with 11.1 mm d-glucose supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Tet System-approved fetal bovine serum, Clontech), antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin), 10 mm HEPES, 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 50 μm β-mercaptoethanol. The cells were cultured with 150 μg/ml G418 sulfate (Clontech) and 100 μg/ml hygromycin B (Invitrogen) to maintain selection pressure. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C under humidified conditions (5% CO2, 95% air). Once cells reached 60–70% confluence in culture, either 24 or 48 h prior to any study, the media were changed to RPMI 1640 medium as above except with 3 mm glucose (G3) and with doxycycline (500 ng/ml) added to induce expression of the DN-HNF-1α mutant gene or without doxycycline for the control. Dox-regulated expression of DN-HNF-1α mRNA was verified by PCR, and protein was verified by Western blotting using an antibody generated against mouse Hnf-1α 70-269 (BD Biosciences). Cell viability was assessed by the trypan blue staining assay. For assessing cell functionality and LC/MS/MS analysis, cells were seeded into 6-well plates and treated with G3 RPMI medium with or without dox for 24 h in advance of the study. For NMR studies of isotopic labeling or entrapment for 31P-measured rates of ATP synthesis, cells were subcultured into 10-cm diameter Petri dishes (three per condition).

Islet Isolation

Islets were isolated from 6- to 10-week-old Hnf-1α (KO, −/−) and age-matched wild type (WT, +/+) littermate mice (4, 5). Breeding pairs of HNF-1α heterozygous (−/+) were the kind gifts from Drs. Moshe Yaniv and Marco Pontoglio and were bred and treated in a manner that complied with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health). Mouse genotype was confirmed from tail snips. Tissue was lysed overnight in lysis buffer containing proteinase K, and DNA was extracted using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit for purification of total DNA (Qiagen). The DNA template was amplified by PCR using premixed tubes from BioNeer (AccuPower PCR pre-mix), and run on a 2% agarose gel.

Mice were fed ad libitum until harvesting of the islets. Islets were isolated as described previously (17). The pancreas was harvested from anesthetized mice (pentobarbital sodium, 50 mg/kg; Abbott), minced and digested with type P collagenase, hand-picked into CMRL (pH 7.4, supplemented with 25 mm HEPES, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin), and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2, 95% air.

Functional Assays of DN-Hnf-1α Cells

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and grown in culture until they reached 60–70% confluence and treated 24 h in advance with 3 mm glucose supplemented with dox for the test cells or without dox for the control. After the 24 h, the cells were preincubated for 0.5 h at low glucose (G3) in Krebs-Ringer buffer (KRB) with 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA to establish basal conditions. The buffer was then replaced with either KRB with glucose at either 3 or 15 mm or 3 mm glucose supplemented with 4 mm glutamine and 10 mm leucine. Media aliquots were taken at the end of the 2-h incubation and immediately centrifuged at low speed (4 °C) to pellet out any cell contamination while avoiding cell disruption. A portion of the supernatant was placed into a clean tube placed on ice and then stored at −20 °C for insulin analysis. Cells in the remaining incubation buffer were placed on ice, washed with ice-cold PBS, and extracted with ice-cold 0.1% Triton for immediate protein determination. The remaining cell lysate was stored −20 °C for total insulin content.

Functional Assays of HNF-1α KO and WT Islets

Islets (50–80) were layered between a slurry of acrylamide gel column beads (Bio-Gel P4G (156-4124)) and perifusion buffer (KRB with 3 mm glucose and 0.2% fatty acid free BSA) within the perifusion chamber. The islets were then perifused (100 μl/min) for a 1-h equilibration period using a Bio-Rep (Miami, FL) perifusion instrument that provides precise temperature and flow control and collection of eluant into 96-well plate format. After the stabilization period, the islets were perifused with the indicated agonists. Perifusate solutions were gassed with 5% CO2, 95% air and maintained at 37 °C. Secreted insulin was determined by ELISA for mouse insulin (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden). At the end of the perifusion, islet DNA was extracted and assayed following the manufacturer's recommended protocol with PicoGreen double strand DNA quantitation reagent kit (Invitrogen).

Quantitative Real Time PCR for mRNA Expression

Cells were extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) from 6-well plates that were treated for 24 h with G3 ± dox as described above. RNA was reverse-transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs) to cDNA using RT-PCR technology (Bio-Rad). Forward and reverse sequence primers (IDT) were designed for each of the genes of interest, and quantitative real time PCR using Fast SYBR Green reagent (Applied Biosystems) was performed on the 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and evaluated using the Sequence Detection software version 1.4 for mRNA expression. Quantitative analysis was determined by Δ/ΔCT method normalized to both the nontreated cells and β-actin message. Reaction efficiencies were determined to be greater than 99% for each gene of interest. Sequences for rat primers used were as follows: GLUT2, 5′-CAA TTT CAT CAT CGC CCT CT-3′ and 5′-TGC AGC AAT TTC GTC AAA AG-3′; glucokinase, 5′-CAG TGG AGC GTG AAG ACA AA-3′ and 5′-CTT GGT CCA ATT GAG GAG GA-3′; liver-type pyruvate kinase, 5′-CGT TCA GCC CAG CTT CTA TC-3′ and 5′-CCT GTC ACC ACA ATC ACC AG-3′; SCS-ATP, 5′-TGT GGT ACG GTT ACA AGG TAC A-3′ and 5′-ACA ACC ATT TTA GCA GCT TCA T-3′; SCS-GTP, 5′-GAG GAA GAG GAA AAG GTG TCT T-3′ and 5′-GAG GAA GAG GAA AAG GTG TCT T-3′; ME1, 5′-ATG GAG AAG GAA GGT TTA TCA AAG-3′ and 5′-GGC TTC TAG GTT CTT CAT TTC TT-3′; ME2, 5′-GGC TTT AGC TGT TAT TCT CTG TGA-3′ and 5′-TGA ATA TTA GCA AGT GAT GGG TAA A-3′; mtPEPCK, 5′-CTG AGG CCT TAG GCT AGC AA-3′ and 5′-CGT GAG GAC AAA TGG GAA GT-3′; UCP2, 5′-AGT TCT ACA CCA AGG GCT CAG A-3′ and 5′-CTC TCG TGC AAT GGT CTT GTA G-3′; adenine nucleotide translocase, 5′-CCC GAT CGA GAG GGT CAA A-3′ and 5′-TGT ACT GTT TCT CTG CAC TGA TCT GT-3′; ACC1, 5′-GGG AAA TAA AGT GAT TGA GAA GGT-3′ and 5′-TAG TGA TCC GCC ATC TTA ATG TAT-3′; HMG-CoA reductase, 5′-CAT GCT GCC AAC ATC GTC A-3′ and 5′-CCC ACA TTC TGT GCT GCA TC-3′; insulin 1, 5′-GCC CAG GCT TTT GTC AAA CA-3′ and 5′-CTC CCC ACA CAC CAG GTA GAG-3′; Insulin 2, 5′-CAG CAC CTT TGT GGT TCT CA-3′ and 5′-CAG TGC CAA GGT CTG AAG GT-3′; Zn2+ transporter, 5′-TCA AGG CCC CCT TCC AA-3′ and 5′-ACC GAG GAT CTC TGC TCG ATA C-3′.

Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation Efficiency

An index of oxidative phosphorylation was calculated from the ratio of the 31P NMR rates of ATP synthesis and fluorometrically measured oxygen consumption rates as described below.

NMR Perifusion Protocol

Entrapped DN-HNF-1α cells were perifused with KRB (0.2% BSA) supplemented with nutrient agonists (1 ml/min, 37 °C) in the bioreactor in the bore of the AVANCE-500 NMR spectrometer. After a pre-equilibration period with 3 mm glucose, 31P NMR spectra and saturation transfer experiments were acquired during step changes in metabolic substrates and inhibitors. 31P NMR spectra were continuously collected in 20-min experiments, with 3–4 measurements collected for each substrate level (15). Substrate concentrations were adjusted by addition of substrate to the perifusate reservoir, thereby ensuring thorough mixing and temperature and oxygen equilibration of the media before reaching the bioreactor. Spectra were acquired at basal glucose concentration of 3 mm and during sequential additions of the glutamine (4 mm) plus leucine (10 mm), glucose (15 mm), or pyruvate (2 mm). ATP synthesis rates were determined by 31P NMR saturation-transfer techniques (15), as described below.

Bioreactor/NMR Spectrometer

To achieve the high cell density necessary for adequate signal to noise at reasonable time intervals, we used a packed bed perfusion bioreactor loaded with cells entrapped within a biocompatible polymer (i.e. alginate). The alginate maintained cell viability and function by allowing for adequate oxygen and nutrient delivery and for removal of waste by-products. The custom-built perifusion system enabled the maintenance and monitoring of well oxygenated cells within the bore of the NMR spectrometer at physiological pH and temperature.

Cell Entrapment

After 24 h of culture in RPMI, 3 mm glucose (±dox), the cells were entrapped in alginate beads of ∼1–2 mm diameter (16). Briefly, the cells were detached from the plate with trypsin and centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in a 3% alginate solution in PBS (w/v). Beads (∼2 mm diameter) were formed by extruding the slurry from a 28-gauge needle into a 1.1% BaCl2 solution. The cells were allowed to recover overnight in a spinner flask with RPMI (G3 ± dox) culture medium.

Cytosolic and Mitochondrial ATP Synthesis Rates

Recently, it has been shown that in the INS-1E cell line, two distinct pools of intracellular Pi can be distinguished with cytosolically and mitochondrially targeted fluorescent pH-sensitive probes (18, 19). The mitochondrial pH was found to have a higher basal pH than the cytosol, and glucose stimulation caused a further alkalinization of the mitochondria but not in the cytosol. Because the chemical shift of Pi is pH-dependent, these results prompted us to investigate whether distinct cytosolic and mitochondrial pools of Pi could be observed, and rates of ATP synthesis were measured, using 31P NMR saturation-transfer experiments.

Chemical shifts were referenced to the α-phosphate of ATP at 10.2 ppm, which is not affected in the range of pH observed in these studies (20). Although a robust Pi-pH titration curve can be obtained from the Pi and phosphocreatine chemical shift differences, the variable concentrations of phosphocreatine under different substrate conditions in our cells led us to choose the α-phosphate resonance of ATP as the frequency reference (20, 21). A calibration curve of Pi chemical shift frequencies with respect to pH was determined with Pi in buffered salt solutions, with the chemical shift difference increasing with pH.

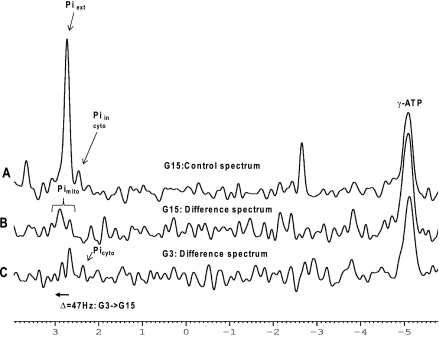

In the standard pulse-acquire spectra, we were able to directly observe an intracellular Pi resonance distinct from the buffer Pi with a pH of ∼7.0 corresponding to the cytosolic compartment (Fig. 4A). With phosphate buffering of KRB at pH 7.4, the extracellular Pi co-resonates with any putative mitochondrial Pi pool and interferes with its direct observation. However, in the difference spectrum (Fig. 4, B and C) of control spectra (Fig. 4A) and the γ-ATP saturation spectra (data not shown), we could measure a metabolically active Pi pool that corresponded to the mitochondrial pH and was responsive to changes in glucose or amino acid stimuli.

FIGURE 4.

Representative 31P NMR spectra of alginate-entrapped DN-HNF-1α control cells (no doxycycline) perifused in oxygenated KRB buffer with 15 mm glucose (spectrum A). The resonances in the control spectrum at G15 (spectrum A) of the saturation transfer experiment (saturation pulse downfield of Pi) correspond to extracellular Pi at 2.73 ppm and intracellular Pi at 2.39 ppm. The difference of the two spectra of the saturation transfer experiment (saturation pulse at γ-ATP, or downfield of Pi) reveals metabolically active intracellular Pi pools with their chemical shifts dependent upon the pH of their respective intracellular compartment. Increasing the glucose from 3 to 15 mm caused a downfield shift of ∼47 Hz in the mitochondrial Pi corresponding to a pH shift of ∼0.3. For ease of comparison, the difference spectra (B and C) are shown inverted. (In the difference spectra, the γ-ATP peaks and Pi peaks are normally negative excursion.)

ATP synthesis rates were calculated as follows: k−1 × [Pi]in, where k−1 is the rate constant k (min−1) = δM/Mo × 1/T1, and [Pi]in is the intracellular Pi concentration. δM/Mo is the change in the intracellular Pi signal when the terminal phosphate of ATP is saturated compared with the Pi signal with a saturation pulse offset an equal distance downfield from the Pi resonance (δM/Mo = (Mo − Mz)/Mo) (15). The longitudinal relaxation time, T1, for both the extracellular and intracellular Pi was measured in separate studies at basal (3 mm) glucose and upon addition of substrates. T1 values were measured using standard inversion-recovery experiments. T1 for extracellular Pi was calculated to be 4.13 s, and T1 for intracellular Pi was calculated to be 1.58 s at basal glucose. Intracellular Pi concentration was calculated from relative signal intensity of the extracellular and intracellular Pi at steady state for each condition, and the measured concentration of intracellular Pi (13.0 ± 1.2 nmol/mg-protein) at basal conditions by tandem mass spectrometry (as described below). The mitochondrial Pi was assumed constant under all conditions, as has been shown in nerve cells as the result of the combined action of Pi and Ca2+ transport into and buffering of Pi by complexation with mitochondrial Ca2+ (22). Variation in the cell number of encapsulated cells and packing within the bioreactor was minimal as shown from the consistency of the relative intensities of the intracellular and extracellular Pi at basal conditions, and it was confirmed by measurement of the protein concentration of the entrapped cells at the end of the study.

Oxygen Consumption Rates

Oxygen consumption rates of freshly trypsinized cells or encapsulated cells were measured using a fiber optic oxygen monitor (model 210, Instech Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA) (23). A 250-μl chamber was loaded with ∼2 × 106 cells or ∼5 beads, and changes in the oxygen concentration were monitored under buffer conditions and substrate additions identical to 31P NMR experiments for measurement of ATP synthesis rates.

Measurement of Mitochondrial Superoxide Production

Mitochondrial superoxide production was evaluated in mitochondria isolated from DN-HNF-1α cells cultured with or without doxycycline for 24 h. The mitochondria were isolated and resuspended in an isotonic buffer as described previously (14). Superoxide production was determined from the oxidation of hydroethidine (HEt) (Molecular Probes, Inc.), using a modification of previously described methods (24). Briefly, the mitochondria were aliquoted into a 96-well plate (∼50 ng of mDNA per well) and equilibrated to 37 °C, and HEt was added at a concentration of 5 μm. The oxidation of HEt was monitored at 5-s intervals as the increase in fluorescence (excitation, 545 nm; emission, 590 nm) with a FlexStation3 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). After a 15-min equilibration period, pyruvate was added (10 mm final concentration), and fluorescence was monitored for an additional 15 min, followed by addition of carbonyl cyanide 4-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, 2 μm final concentration) to collapse the mitochondrial membrane potential and determine the rate of HEt oxidation independent of superoxide production. Rates of HEt oxidation due to reaction with superoxide were calculated from the difference in the slope of the time-dependent changes in fluorescence before and after addition of FCCP.

13C-Isotopomer and Metabolomic Assessment of Anaplerosis

Cells treated with G3 ± dox as described above, and at 80–90% confluence, were preincubated for 0.5 h at 3 mm glucose in KRB to establish basal conditions. The cells were then washed to remove unlabeled glucose and then incubated up to 2 h in KRB with either natural abundance glucose or [U-13C]glucose alone (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Miamisburg, OH, 99% 13C, 3 or 15 mm) or supplemented with 4 mm glutamine and 10 mm leucine. Media aliquots were taken and placed on ice for insulin analysis at 0, 1, and 2 h. At the end of the 2-h isotopic labeling period, the media were removed and frozen for later analysis.

13C NMR Analysis of Isotopomer Distribution

The 13C positional isotopomer distribution of glutamate was determined by 13C NMR spectroscopy with an AVANCE 500-MHz spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Inc. Billerica, MA) (13, 14). Spectra were acquired with TR = 0.5s, 10,000 scans, 16 K data, and Waltz-16 broadband proton decoupling. Correction factors for differences in T1 relaxation times and nuclear Overhauser effects were determined from fully relaxed spectra of standard solutions (13, 14). We used the program “tcacalc” to calculate the relative fluxes of labeled and unlabeled substrates into the Krebs cycle from the NMR positional isotopomer distribution of glutamate as described previously (12–14).

Metabolomics by LC/MS/MS Analysis

For LC/MS/MS analysis the monolayer of cells was quenched with ice-cold acetonitrile/water (1:1) with 2 mm ammonium acetate and 10 μm d4-taurine. Cells were immediately scraped, vortexed briefly, and centrifuged (2,000 relative centrifugal force for 5 min at 4 °C). The supernatant was transferred to a 0.22 low binding polyvinylidene difluoride membrane centrifugal filter device (Millipore Corp.). The supernatant was analyzed by LC/MS/MS for metabolite concentrations where extracts were normalized to taurine spectra with d4-taurine as an internal standard. For normalization, we explored the possibility of using an endogenous cellular metabolite as an internal standard for quantitative analysis. We hypothesized that because taurine is relatively abundant and helps buffer osmolarity within the cell, its concentration would be relatively stable under our experimental conditions, and that it could therefore provide a convenient and naturally occurring internal standard of our cells. To test whether taurine could prove useful as an internal concentration standard under low (3 mm) and high (15 mm) glucose concentrations, we added a known mass of an isotopically labeled taurine (d4-taurine) to the cell extracts, and normalized the LC/MS/MS measured signal intensity to protein in the dox-treated and nontreated HNF-1α cell line. Taurine concentrations (nmol/mg-protein) were unaffected by glucose concentrations or 24-h dox treatment (G3: no dox, 11.9 ± 0.5, plus dox, 11.2 ± 1.7; G15: no dox, 13.2 ± 1.1, plus dox, 11.5 ± 0.5). All metabolite concentrations determined by tandem mass spectroscopy were referenced to an average taurine concentration of 12.0 nmol/mg-protein.

LC/MS/MS analysis of metabolites was performed on an Applied Biosystems API4000 QTrap interfaced to a Shimadzu HPLC (LC-20AD, SIL-20AC, and CTO-20A). Metabolites were eluted from a Dionex Aclaim Polar Advantage column (C16, 5 μm, 120 Å, 4.5 × 250 mm) (40 °C) with acetonitrile/water buffered with 2 mm ammonium acetate using a linear gradient from 5 to 95% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 600 μl/min. Metabolite concentrations were determined by electrospray ionization monitoring of the positive product ion transition pairs of aspartate (132/88), ATP (506/159), ADP (426/159), citrate (191/87), succinate (117/73), glutamate (146/128), lactate (89/43), malate (133/71), pyruvate (87/32), taurine (124/80), and d4-taurine (128/80). Isotopic labeling was monitored with incremental increases in the masses of the parent and daughter ions to quantify isotopic isomers.

Metabolite Analysis in Cells

Glucose concentration in the media was determined by the glucose oxidase reaction (Glucose Analyzer II; Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). Total protein was measured spectrophotometrically, based on the method of Biuret assay using the Micro-BCA assay kit (Pierce). Insulin secreted and total insulin were determined by ELISA for rat insulin (Mercodia, ALPCO Diagnostics).

Statistical Analyses

All data are reported as mean ± S.E. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t tests were used to test for comparisons between groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Changes in mRNA of Downstream Targets of HNF-1α

Induction of the DN-HNF-1α protein by 24-h culture with doxycycline was confirmed by Western blot analysis of the cell extracts using an antibody directed against amino acid residues 70–269 of mouse HNF-1α (Fig. 1A). The native mouse HNF-1α protein at 92 kDa is seen in both the control cells and cells cultured with doxycycline, whereas the human DN-HNF-1α protein, at 45 kDa, is highly expressed only in those cells cultured with doxycycline (7). In contrast to the earlier study that used an antibody directed against the human DN-HNF-1α protein and does not cross-react with the native mouse HNF-1α (7), the antibody that we used has cross-reactivity to both mouse and human HNF-1α and indicates that both the native mouse and human DN-HNF-1α are present in these clonal cell lines.

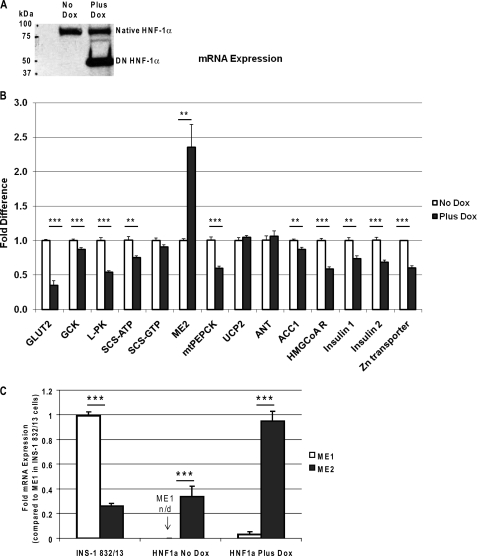

FIGURE 1.

A, Western blot analysis of induction of DN-HNF-1α by doxycycline in INS-1 cells. Extracts from DN-HNF-1α cells cultured for 24 h with and without 500 ng·ml doxycycline were resolved in 9% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted against an antibody directed against amino acid residues 70–269 of mouse HNF-1α. B, effects of DN-HNF-1α on HNF1α target genes. RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed from cells that were cultured in RPMI with 3 mm glucose with or without 500 ng/ml of doxycycline for 24 h. All cDNA samples for quantitative RT-PCR were normalized to β-actin expression and compared with the non-dox-treated control cells. C, effects of DN-HNF-1α on relative mRNA expression levels of cytosolic malic enzyme 1 (ME1) and mitochondrial malic enzyme (ME2) isoforms referenced to expression in the clonal INS-1 832/13 cell line. mRNA expression of the HNF1α mutant INS-1, nontreated INS-1 and INS-1 832/13 cells, all with similar β-actin CTs, were normalized to β-actin expression and compared with ME1 expression in INS-1 832/13 cells. Data were analyzed using Δ/ΔCT method. Data are mean ± S.E., with significance determined by Student's t test (no dox versus plus dox: ***, p < 0.001, **, p < 0.01).

mRNA expression levels in the DN-HNF-1α cells under the regulation of doxycycline were measured and compared with the nontreated controls using quantitative RT-PCR. All expression levels were measured under basal condition of 3 mm glucose. DNA amplification efficiencies were greater than 99% for all primers sets. After 24-h dox induction of DN-HNF-1α, we measured marked reductions in the expression levels of GLUT2, 65% (n = 9, p = 0.0001), and liver-type pyruvate kinase, 46% (n = 6, p = 1e-5) (Fig. 1B). The reduced expression levels of GLUT2 and liver-type pyruvate kinase are the result of dominant-negative action of the mutant protein upon HNF-1α transcription activation of the respective promoters of GLUT2 and liver-type pyruvate kinase (7). In islets from the Hnf-1α KO mice, GLUT2 expression (n = 3, p = 0.003) was significantly reduced by ∼90% (data not shown), as reported previously (5), but no change in glucokinase mRNA expression was measured. A modest, but significant, decrease in expression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC1) and glucokinase mRNA was observed after 24 h of doxycycline treatment. Insulin (1 and 2) and HMG-CoA reductase expression levels in the HNF-1α mutant cells were significantly reduced, ∼30% (n = 6, p = 0.0008 and 0.0001, respectively), for both insulin isoforms and 41% (n = 6, p = 3e-6) for HMG-CoA reductase. Thus, 24 h of dox treatment produces similar reductions to those seen after 48 h of dox treatment for mRNA expression of enzymes and proteins linked to insulin secretion (7). Expression levels of ACC1, glucokinase, and HMG-CoA reductase were unaffected in the Hnf-1α KO mouse islet.

Not previously reported, but integral to normal insulin secretory processing, we also observed a 39% decrease in zinc transporter (n = 6, p = 1e-5) expression in the DN-HNF-1α cells. mRNA expression levels of the mitochondrial proteins, UCP2 and adenine nucleotide translocase, both of which have been suggested as regulators of mitochondrial proton leak (27), were unchanged with 24 h of dox treatment. In contrast to the INS-1 832/13 cell line, cytosolic ME1 (malic enzyme 1) expression was undetectable in this modified HNF-1α cell line (Fig. 1C). However, mitochondrial ME2 (malic enzyme 2) mRNA expression was similar to INS-1 832/13 cells (14). Doxycycline-induced overexpression of DN-HNF-1α increased ME2 expression over 2-fold to a point that was equivalent to ME1 expression in the INS-1 832/13 cells and induced a slight elevation in ME1 expression (Fig. 1C).

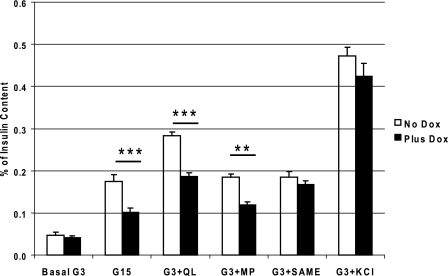

Insulin Secretion of DN-HNF-1α Cells

Defects in insulin secretion were observed in the cells with DN-HNF-1α gene expression compared with the nontreated cells. The RPMI growth medium was changed to 3 mm glucose RPMI with or without addition of 500 ng/ml doxycycline with all of the other culture components 24 h prior to the insulin secretion stimulatory experiment. Insulin secretion was determined after a 2-h incubation in KRB at 3 mm basal glucose (G3) and with the following nutrient stimuli: 15 mm glucose (G15), G3 with 4 mm glutamine and 10 mm leucine (G3 + QL), G3 with 10 mm methyl pyruvate (G3 + MP), G3 with 10 mm monomethyl succinate (G3 + SAME), or G3 with 30 mm KCl (G3 + KCl). All stimulatory conditions significantly (p < 0.05) increased insulin secretion rates above basal level for both the dox- and nontreated cells, although most rates for the DN-HNF-1α cells were blunted in comparison with the control cells (Fig. 2). When normalized to either cellular protein (data not shown) or total insulin, the mutant cells secreted significantly less insulin than the control cells when stimulated with G15, G3 + QL, and G3 + MP (Fig. 2). Interestingly, no decrease in insulin secretion was measured in response to SAME when normalized to either protein or total insulin content. Earlier studies have shown that expression of HNF-1α-p291fsinsC decreased gene transcription of the oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (7). By entering downstream of this block in Krebs cycle metabolism, the metabolism of the methyl ester of succinate is unaffected resulting in comparable rates of insulin secretion. The insulin secretory response to KCl was the same in both groups and was especially apparent when the data were normalized to total insulin content, indicating that the observed changes in insulin secretion in response to nutrient secretagogues were because of metabolic changes and not to defects in Ca2+-mediated exocytosis following potassium-induced membrane depolarization.

FIGURE 2.

Effects of DN-HNF-1α on insulin secretion. Cumulative rates of insulin secretion from doxycycline-induced DN-HNF-1α INS-1 cell static incubations were compared with nontreated (minus doxycycline) cells. Cells were placed in 3 mm glucose culture media minus or plus doxycycline 24 h prior to the incubation. On the day of the study, cells were equilibrated for 0.5 h and incubated in KRB with 0.2% BSA (37 °C) and the specified substrates. G3, 3 mm glucose; G15, 15 mm glucose; G3 + QL, G3 plus 4 mm glutamine and 10 mm leucine; G3 + MP, G3 plus 10 mm methyl pyruvate; G3 + SAME, G3 plus 4 mm succinic acid methyl ester; G3 + KCl, G3 plus 30 mm KCl. Insulin was analyzed by ELISA and normalized to total cellular insulin. Data are mean ± S.E. of a minimum of three repeated measures for each condition, with significance determined by Student's t test (no dox versus plus dox: ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01). All conditions resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) increase in rate of insulin secretion compared with the basal rate.

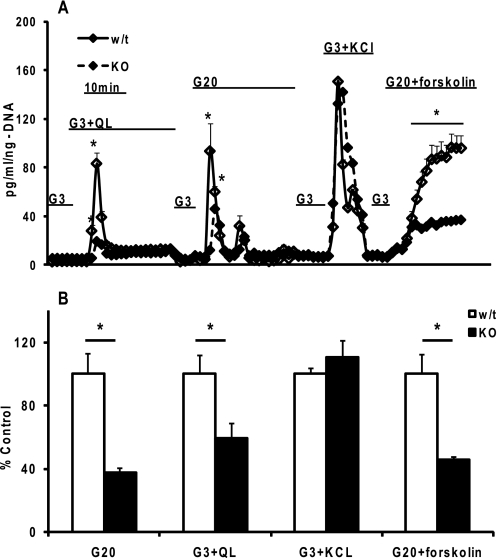

Insulin Secretory Responses from Islets of HNF-1α KO Mice

The islets from the Hnf-1α KO mice tended to be smaller with distinct differences in appearance and density. To eliminate differences in secretion rates due to islet size and cell number, we normalized the secretion rates to cellular DNA. In response to 20 mm glucose, and the combination of glutamine and leucine in the presence of 3 mm glucose, islets from both the Hnf-1α KO and WT mice consisted of a prominent first-phase insulin release with a minimal sustained second-phase release (Fig. 3). The Hnf-1α KO islets however had a blunted secretory response in comparison with their WT littermates. When depolarization was induced with elevated KCl, both the KO and WT islets had similar rates of insulin release. Finally, we tested the responsiveness of the KO islets to potentiation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion when cAMP concentrations are increased by forskolin treatment (18). As with the other nutrient secretagogues, the KO islets had a diminished response to 20 mm glucose plus forskolin. But compared with 20 mm glucose alone, the proportional increase of secretion, and hence the potentiation, was comparable with that of the WT islets.

FIGURE 3.

Insulin secretion from islets isolated from HNF-1α KO mice and WT littermates. A, islets (50–80) were layered between a slurry of acrylamide gel column beads (Bio-Gel P4G (156-4124)) and KRB with 3 mm glucose and loaded into the perifusion chamber. After a 1-h equilibration period, the islets were perifused at 100 μl/min with well oxygenated 3 mm KRB (37 °C). The islets were then perifused with the indicated agonists as follows: G3, 3 mm glucose; G3 + QL, G3 plus 4 mm glutamine and 10 mm leucine; G20, 20 mm glucose; G3 + KCl, G3 plus 30 mm KCl; G20 + forskolin, G20 plus 10 μm forskolin. Secreted insulin was normalized to islet DNA. We typically performed simultaneous perifusions of two to three chambers for both the KO and WT islets for each session. B, mean integrated area under the insulin secretion curves from A were determined for each condition for the KO and WT islets. Data are mean ± S.E. of a two independent islet preparations with duplicate or triplicate perifusions from the same islet preparation. Significance was determined by Student's t test (*, p < 0.05 comparison of WT to KO).

Cytosolic and Mitochondrial ATP Synthesis Rates

We employed saturation transfer 31P NMR experiments to identify metabolically active pools of inorganic phosphate used for the synthesis of ATP. Under our experimental conditions, the media were buffered at pH 7.4, and the extracellular Pi peak appears at 2.72 ppm and an intracellular Pi pool at 2.39 ppm (Fig. 4A). The compartmental location of the intracellular pool is unspecified, but by performing saturation transfer experiments, we observed two metabolically active Pi pools, one at 2.37 ppm and a second at 2.67 ppm (Fig. 4, B and C). Upon increasing the glucose concentration to 15 mm, we observed an ∼10-fold drop in the intracellular Pi signal at 2.37 ppm. In the saturation transfer experiment, the metabolically active Pi peak was shifted 47 Hz further downfield with the increase in glucose from 3 mm (Fig. 4C) to 15 mm (Fig. 4B). The correspondence of our NMR measured pH of these two Pi pools with independent measures of the cytosolic and mitochondria pH led us to assign the upfield peak at 2.39 ppm to the cytosolic Pi (∼pH 7.0) and downfield peaks at ∼2.7 ppm, and above, to the mitochondrial Pi (pH 7.25 to 7.48). When the glucose was increased to 15 mm, we observed an alkaline shift of ∼0.3 pH units in the NMR spectra (∼47 Hz downfield) in good agreement with the alkalinization of the mitochondria measured with a mitochondrially targeted fluorescent pH-sensitive probe (19), lending further confidence to the peak assignments.

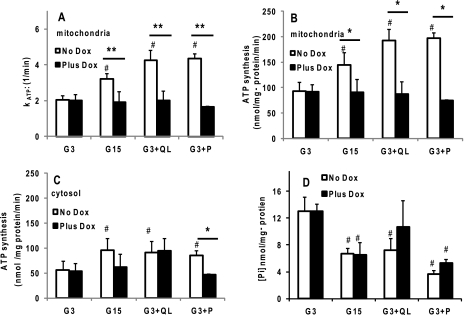

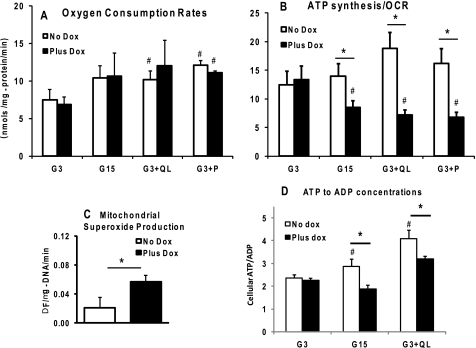

From the change in the intensity of the intracellular Pi resonance when saturating the γ-phosphate of ATP, we calculated the rate constant for ATP synthesis, kATP. Overexpression of DN-HNF-1α completely abrogated the marked increases in mitochondrial kATP seen in the control cells with the addition of each of the secretagogues, G15, G3 + QL, or G3 + P (Fig. 5A). 31P NMR calculated rates of both mitochondrial (Fig. 5B) and cytosolic (Fig. 5C) ATP synthesis were increased ∼1.5–2-fold in the control cells for nutrient secretagogues. Rates of ATP synthesis in the DN-HNF-1α cells were essentially unresponsive to nutrient stimuli (Fig. 5, B and C) because of the combined effect of little or no change in kATP and the drop in intracellular Pi concentration (Fig. 5D). However, we observed similar changes in oxygen consumption rates (OCR) for both the control and the DN-HNF-1α cells under all conditions (Fig. 6A). The ratio of ATP synthesis rate and OCR can be interpreted as an index of oxidative phosphorylation (15, 25), and the reduction in this ratio in the DN-HNF-1α cells compared with the controls is indicative of increased mitochondrial uncoupling (Fig. 6B). The net effect of the uncoupling would be a loss of insulin secretion triggered by the increase in the ATP/ADP ratio (Fig. 6D) and closure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channels.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of DN-HNF-1α on parameters of ATP synthesis in response to nutrient secretagogues measured by 31P NMR saturation transfer experiments as described under “Experimental Procedures” and in Fig. 5. Cells were cultured as described in Fig. 2. Parameters were measured in KRB with basal glucose concentration of 3 mm (G3), stimulatory glucose of 15 mm (G15), G3 plus 4 mm glutamine (Q) and 10 mm leucine (L), and G3 plus 2 mm pyruvate (P). A, rate constant (kATP) for unidirectional ATP synthesis in mitochondria. B, mitochondrial ATP synthesis rates calculated from the mitochondrial rate constant and cytosolic Pi concentration at t = 0. C, cytosolic ATP synthesis rates calculated from the cytosolic rate constant and cytosolic Pi concentration. D, cytosolic Pi concentration calculated from the 31P NMR peak intensity of intracellular Pi normalized to the constant extracellular Pi and from LC/MS/MS determined concentration. Data are mean ± S.E. of four to six NMR-perifusion experiments for each condition, with significance determined by Student's t test (no dox versus plus dox: **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05, compared with basal: #, p < 0.05).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of DN-HNF-1α on OCR, mitochondrial uncoupling, superoxide production, and ATP/ADP concentrations. Cells were cultured as described in Fig. 2 (except without BSA) and under “Experimental Procedures.” A, OCRs were measured after a 1-h pre-equilibration in KRB (G3, 37 °C) prior to transfer to chamber and OCR measurements. OCRs were measured in KRB (37 °C) with basal glucose concentration of 3 mm (G3), stimulatory glucose of 15 mm (G15), G3 plus 4 mm glutamine (Q), and 10 mm leucine (L), and G3 plus 2 mm pyruvate. B, index of oxidative phosphorylation efficiency was calculated as the ratio of mitochondrial ATP synthesis rates (Fig. 5B) and OCR (A). Data are mean ± S.E. of a minimum of three repeated measures for each condition. C, mitochondrial superoxide production was evaluated in mitochondria isolated from DN-HNF-1α cells cultured with or without doxycycline for 24 h. The mitochondria were isolated and resuspended in an isotonic buffer as described previously (13), and superoxide production was determined from the oxidation of HEt (Molecular Probes, Inc). Mitochondria were aliquoted into a 96-well plate (∼50 ng of mDNA per well) and equilibrated to 37 °C, and HEt was added at a concentration of 5 μm. Oxidation of HEt was monitored at 5-s intervals by measuring the change in fluorescence (excitation, 545 nm; emission, 590 nm) with a FlexStation3 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) during a 15-min equilibration period, a 15-min stimulus period with pyruvate at 10 mm, and for 15 min after the addition of FCCP (2 μm final concentration). Rates of HEt reaction with superoxide were calculated from the slope before and after addition of FCCP. D, total cellular ATP/ADP ratios were measured following a 1-h preincubation in KRB with 3 mm glucose, and an additional 2-h incubation in KRB with glucose at either 3, 15, or 3 mm with glutamine (4 mm) and leucine (10 mm). Cells were extracted with ice-cold acetonitrile/water at 5 and 10 min, and the nucleotide concentrations were determined by LC/MS/MS as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are mean ± S.E. determined in triplicate with two independent experiments for each condition. Significance was determined by Student's t test (no dox versus plus dox: *, p < 0.05; compared with basal: #, p < 0.05).

Increased Mitochondrial Superoxide Production in DN-HNF-1α Cells

The observed increase in uncoupling activity in the DN-HNF-1α cells without any detectable up-regulation of UCP2 mRNA led us to hypothesize that an increased concentration of an activator of UCP2 may account for the increased uncoupling in the DN-HNF-1α cells. Previously, Kraus et al. (24) have presented compelling evidence indicating that superoxide is an activator of UCP2 uncoupling activity in islets. We therefore measured superoxide production rates in isolated mitochondria. Under metabolic conditions representative of GSIS (i.e. 10 mm pyruvate), we measured a 3-fold increase in superoxide production by mitochondria isolated from cells expressing the DN-HNF-1α (Fig. 6C), which may be responsible for the increased uncoupling activity of the cells when supplied with nutrient secretagogues.

Metabolic Pathways by 13C NMR Isotopomer Analysis

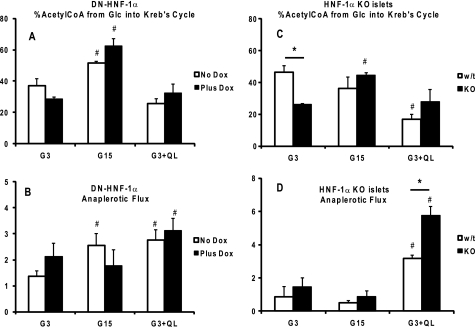

Analysis of the isotopomer distribution of glutamate was used to assess whether changes in the expression levels of the genes controlled by HNF-1α led to any observable changes in the relative fluxes through PDH and anaplerotic inputs into the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Although no change in PDH flux was observed with the addition of glutamine and leucine, raising glucose to 15 mm led to similar increases in the relative proportion of glucose flux through PDH (Fig. 7A) for both control and DN-HNF-1α cells. Similar responses were noted in the isolated islets. Increasing glucose to 15 mm resulted in a shift toward glucose flux through PDH for the Hnf-1α KO islets (Fig. 7C). It should be noted however that tcacalc only provides information with regard to relative flux rates, and the increase in relative PDH flux with G15 may not be due to an increase in glucose utilization but would be indicative of a shift in substrate preference to glucose.

FIGURE 7.

Steady-state flux rates relative to Krebs cycle flux rate. DN-HNF-1α cells ± dox, or islets from HNF-1α KO and WT littermate mice, were cultured as described in Fig. 2 and under “Experimental Procedures.” After a 2-h preincubation in KRB (G3), the medium was replaced with KRB with [U-13C]glucose at either 3, 15, or 3 mm with glutamine (4 mm) and leucine (10 mm). After a 2-h incubation, cellular extracts were prepared, and the 13C-isotopic positional enrichment was determined by 13C NMR spectroscopy or LC tandem-mass spectrometry as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Pathways were calculated using the program “tcacalc” (9–11), for PDH flux from exogenous glucose (A, cells; C, islets) and total anaplerotic flux from all sources (B, cells; D, islets). Data are means ± S.E. of a minimum of four to five repeated measures for each condition, with significance determined by Student's t test (wild type to KO: p < 0.05; compared with basal: #, p < 0.05).

As reported previously for INS-1 832/13 cells, we observed an increase in relative anaplerotic flux rates in the control cells with the addition of nutrient secretagogues (13, 14). In contrast, only the addition of glutamine and leucine enhanced anaplerotic flux in the mutant HNF-1α cells. Increasing glucose had no observable effect on the relative proportion of anaplerotic flux to tricarboxylic acid cycle flux in the dox-treated cells (Fig. 7B). In the islets, there was no observable increase in anaplerosis relative to Krebs cycle flux with G15. The addition of glutamine and leucine, however, resulted in a marked increase in anaplerosis for both the WT and Hnf-1α KO islets (Fig. 7D).

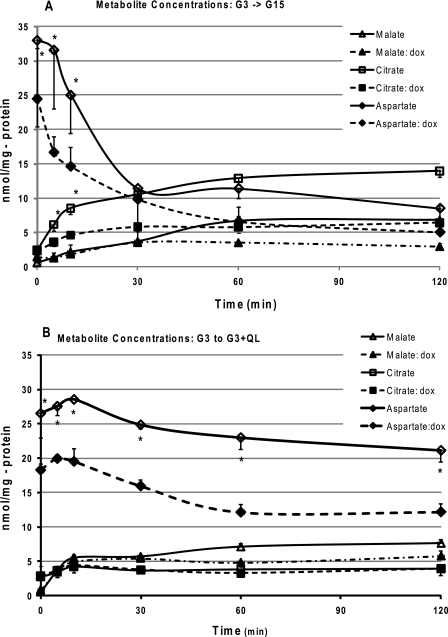

Metabolomics Analysis of Anaplerosis

To further evaluate the effects of the expression of the dominant-negative HNF-1α mutant, or the loss of Hnf-1α gene on anaplerosis, we used tandem mass spectroscopy to measure the time-dependent changes in the concentrations of the major products of anaplerosis, citrate and malate, in response to either high glucose (G15) or to G3 supplemented with the amino acids, glutamine plus leucine. The initial rates of synthesis or disappearance were calculated from the exponential fit to the time-concentration curves (Fig. 8, A and B). Addition of either nutrient secretagogue resulted in an increase in the appearance of both citrate and malate that reached a steady-state concentration within ∼30 min. In general agreement with the results of our isotopomer analysis of anaplerosis (Fig. 7B), the initial rates of synthesis of citrate was clearly reduced in the mutant HNF-1α cells when exposed to G15 (Table 1), as well as the steady-state change in the combined citrate-malate pool (Table 2). Surprisingly, with the amino acid stimulus (G3 + QL), we observed a higher initial rate of citrate synthesis in the DN-HNF-1α cells (Table 1), although the change in the citrate-malate pool was comparable with the control cells (Table 2).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of DN-HNF-1α on changes in the concentrations of the anaplerotic products, citrate and malate, and aspartate in response to insulin secretagogues. Cells were cultured as described in Fig. 2 (without BSA) under “Experimental Procedures.”. After a 2-h preincubation in KRB (G3), the media were replaced with KRB with glucose at either 15 mm (A) or 3 mm (B) with glutamine (4 mm) and leucine (10 mm). Cells were extracted with ice-cold acetonitrile/water at the designated times, and the malate and citrate concentrations were determined by LC/MS/MS as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are means ± S.E. determined in triplicate for two independent experiments for each time point, with significance determined by Student's t test (no dox versus plus dox: *, p < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Effects of DN-HNF-1α on initial rates in response to nutrient secretagogues

Initial rates (nmol/mg-protein/min) of net synthesis of citrate, malate, and aspartate were determined from the exponential fit to the mean concentration time course of each metabolite (Fig. 8, A and B). Mean (±S.E.) concentrations were determined in triplicate for two independent experiments for each time point. After a 0.5-h preincubation in KRB (G3), cells were incubated with either G15 or G3 + 4 mm Gln + 10 mm Leu for up to 2 h. Cells were quenched at select intervals, extracted for LC/MS/MS analysis, and concentrations determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

| Metabolite | G3 → G15 |

G3 → G3QL |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dox | Plus dox | No dox | Plus dox | |

| Citrate | 0.621 ± 0.090 | 0.316 ± 0.050a | 0.299 ± 0.050 | 0.461 ± 0.077a |

| Malate | 0.177 ± 0.071 | 0.133 ± 0.023 | 0.784 ± 0.054 | 0.840 ± 0.084 |

| Aspartate | −0.738 ± 0.041 | −0.410 ± 0.027a | −0.077 ± 0.004 | −0.107 ± 0.007 |

a p <0.05 compared with controls (No dox).

TABLE 2.

Change of metabolite concentrations (nmol/mg-protein) at steady state in response to nutrient secretagogues in DN-HNF-1α cells and HNF-1α KO islets

Changes in the total cellular, or islet, concentration of citrate, malate, and aspartate were determined following a 2-h incubation (0.5-h preincubation in KRB (G3)) with either G15 or G3 + 4 mm Gln + 10 mm Leu. Cells and islets were quenched, extracted for LC/MS/MS analysis, and concentrations determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Mean (±S.E.) concentrations were determined in triplicate for two independent experiments for each time point. All changes were significantly different from basal concentrations (p < 0.05).

| Metabolite | DN-HNF-1α:G3 → G15 |

DN-HNF-1α:G3 → G3QL |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dox | Plus dox | No dox | Plus dox | |

| Cells | ||||

| Citrate + malate | 17.7 ± 0.2 | 5.7 ± 0.6a | 8.3 ± 0.4 | 6.0 ± 0.7a |

| Aspartate | −24.5 ± 3.5 | −19.4 ± 2.1 | −5.4 ± 0.3 | −6.1 ± 0.5 |

| Islets | WT | KO | WT | KO |

| Citrate + malate | 4.8 ± 0.89 | 1.9 ± 0.85a | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 0.8 |

a p <0.05 compared with controls (Cells, no dox; islets, WT).

In the isolated islets, the steady-state concentrations of the malate-citrate pools were increased for both the WT and Hnf-1α KO mice (Table 2). In response to G15, the increase in the KO islets was less than half of that seen in the WT islets. The significantly blunted GSIS of the KO islets can be explained in large measure by the marked reduction in Glut2 expression. However, the potentiation of the GSIS by addition of forskolin suggests that glucose transport is not saturated even with this minimal expression level of Glut2. Forskolin potentiates nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion by the protein kinase A/cAMP signaling pathway by activating adenylate cyclase, but it is only effective with stimulatory concentrations of nutrients (18). Previously, it has been suggested that the blunted secretory response to glutamine plus leucine can be attributed to decreased expression and protein of Nbat (neutral and basic amino acid transporter) (5). The similar increase in the anaplerotic products, citrate and malate (Table 2), argue against any marked defect in amino acid transport and metabolism by the mitochondria when the KO islets were challenged with glutamine and leucine.

Our previous steady-state analysis had indicated that a substantial fraction of anaplerosis entering at the level of oxaloacetate was derived from a source other than pyruvate (13). The results of this study point to aspartate as a likely source for this unidentified substrate. In response to either nutrient secretagogues, we found a rapid decrease in aspartate concentration with dynamic changes similar to those observed for citrate and malate (Fig. 8, A and B). The initial rates of aspartate disappearance were remarkably similar to the appearance rates of citrate and malate (Table 1). Thus, the initial increase (up to ∼30 min for G15 and ∼60 min for G3 + QL) in citrate and malate may be mostly derived from aspartate. As well, we found that increases in the steady-state concentrations of the citrate/malate pools could be accounted for by the decrease in the aspartate concentration (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

MODY-3 is the result of dominant-negative mutations in the HNF-1α transcription factor causing a severe impairment in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Multiple downstream targets of DN-HNF-1α have been identified that could interfere with metabolic pathways in both the cytosol and in the mitochondria. This study, using DN-HNF-1α cells, demonstrates that mutations of HNF-1α lead to mitochondrial dysfunction of metabolism and energy production. Using a 31P NMR approach, we were able to specifically measure rates of mitochondrial ATP production and show substantial increases in the uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the DN-HNF-1α cells. Also, using an isotopic labeling approach combined with metabolomic analyses, we show that anaplerosis is also affected to reduce the generation of mitochondrial second messengers. These metabolic changes in the mitochondria can be attributed to changes in the expression of the downstream targets of the HNF-1α transcription factor resulting in impaired nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion. Our pathway analysis indicated similar effects in islets isolated from Hnf-1α KO mice, suggestive of similar perturbations in the mitochondrial function with loss of HNF-1α.

DN-HNF-1α Decreases Mitochondrial ATP Synthesis but Not Oxygen Consumption

The observation and assignment of distinct compartments of Pi in in vivo NMR spectroscopy is an area of active research with clear evidence of NMR-observable Pi in the intracellular and extracellular space in brain (26). In this study, we have attempted to identify distinct intracellular pools following earlier studies that indicated that the rate of Pi exchange between cytosol and mitochondria is sufficiently slow to allow one to observe two intracellular Pi peaks (27). Furthermore, it was possible to assign these two 31P NMR Pi peaks to the mitochondrial Pi and to the cytosolic Pi with their resolution dependent upon the pH of each compartment (19, 27).

From our 31P NMR saturation-transfer experiments, we could identify distinct pools of Pi that were metabolically active for the synthesis of ATP and determine the pH of each Pi compartment. From independently measured mitochondrial pH using the mitochondria-targeted pH-sensitive protein (mtAlpHi) (19), we were able to assign the downfield resonances (∼2.7 to ∼2.9 ppm) to the mitochondrial pool and the upfield resonances (∼2.4 ppm) to the cytosolic pools. In the control cells, both of these pools proved to be metabolically active, from the observed increase in kATP under conditions promoting insulin secretion. In the mitochondrial pool, the alkalinization of the mitochondrial matrix with the elevation of glucose to 15 mm has been suggested to be an additional factor that may play a role in augmenting insulin secretion (19).

The observed changes in the cytosolic rate constant are because of substrate level phosphorylation, and may reflect both increased glycolytic flux or an artifact of the reversible reactions catalyzed by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) coupled with phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK). Previous studies examining the magnitude of this cytosolic component to NMR measured rates of ATP synthesis concluded that the reversible GAPDH/PGK exchange reactions may make a measurable contribution in mammalian cell lines with high glycolytic capacity, such as these β-cells (28). High rates of GAPDH/PGK exchange may also account for the anomalous increase in cytosolic rates of ATP synthesis with the additions of glutamine and leucine and of pyruvate (Fig. 5C) as the result of the activities of mitochondrial malic enzyme 2 and of mtPEPCK (Fig. 1). From our prior studies, we believe that the pyruvate produced by ME2 catalysis would be retained within the mitochondria and be channeled directly to either PDH or PC (14). The increased supply of mitochondrial pyruvate by the activity of ME2 reduces the need for cytosolic pyruvate flux into the mitochondria and promotes increased GAPDH/PGK exchange. Our isotopomer analysis indicates that flux of exogenous glucose through PDH (Fig. 7A) is unchanged with the addition of glutamine and leucine to G3, supporting the idea that increased cytosolic ATP synthesis may be explained by an increase of GAPDH/PGK exchange. Thus, the differences in cytosolic ATP synthesis rates measured by NMR may not be necessarily directly proportional to glycolytic flux rates.

Cytosolic ATP synthesis rates, independent of glycolytic flux, could also be due to the activity of mtPEPCK, which would shunt excess oxaloacetate out of the mitochondria as phosphoenolpyruvate and ATP synthesis by protein kinase or GAPDH/PGK. It should be noted that although earlier reports indicate the absence of PEPCK in islets and β-cell lines (29, 30), we believe that the methods used previously were optimized for measuring the activity and gene expression of the cytosolic isoform of PEPCK, and were not suited for measuring the mitochondrial isoform of PEPCK. Real time PCR indicates measurable expression of mtPEPCK in the engineered INS-1 cell line used here, in the INS-1 832/13 cells, and in rat islets. Substrate cycling of pyruvate by either mtPEPCK or malic enzyme could also lead to an overestimate of [14C]pyruvate oxidation when measured by 14CO2 release, but would not affect oxygen consumption. This could explain the discrepancy between the results of Wang et al. (7), who reported a decreased rate of [14C]pyruvate oxidation in DN-HNF-1α cells, and our results of similar OCRs in both the control and DN-HNF-1α when supplied with pyruvate (Fig. 5A). An increase in pyruvate cycling would lead to an increase in 14CO2 release from the labeled pyruvate while bypassing the reduction of NADH by turns of the Krebs cycle. If pyruvate were to enter at OAA, be converted to malate via the reversible reaction of malate dehydrogenase, the equilibration with fumarate would lead to evolution of 14CO2 from the activity of either malic enzyme and/or mtPEPCK. In the β-cell, recent data suggest that cycling through mitochondrial PEPCK can contribute up to 40% of phosphoenolpyruvate pool.3 Lower rates of mtPEPCK expression and activity in the DN-HNF-1α cells would lead to a decrease in pyruvate cycling and 14CO2 evolution even in the face of equivalent rates of electron transport chain and of oxygen consumption.

The majority of methods used to study the coupling of insulin release with glucose metabolism and mitochondrial ATP synthesis employs the indirect measures of changes in ATP concentration. In contrast, the 31P NMR saturation transfer experiments that we used directly measured the changes in ATP synthesis in intact respiring cells in response to secretagogues. In addition to directly measuring rates of ATP synthesis, the NMR experiments simultaneously provide a direct measure of mitochondrial membrane potential as proportional to the rate constant of ATP synthesis, kATP. Uniquely, these NMR experiments provide both the mitochondrial and the cytosolic contributions to the overall ATP synthesis rates.

In the control cells, nutrients that stimulated insulin secretion increased the rate constant of ATP synthesis, kATP, by a factor of 2 or more. In contrast, there was little or no change in the dox-treated cells (Fig. 5A). In the Hnf-1α KO mice, it has been suggested that the impaired metabolic response is due solely to a deficiency in glycolytic flux (4), whereas in the DN-HNF-1α cells, a mitochondrial dysfunction has also been identified as a contributing factor (7, 8). Our results, using two independent approaches, suggest that a mitochondrial defect is also present. First, we treated the cells with nutrient secretagogues that bypass glycolysis (glutamine plus leucine), and we found a blunted stimulation of the ATP synthesis rate constant in the DN-HNF-1α overexpresser. It has been suggested that mutations in HNF-1α lead to impaired amino acid uptake (4), rather than mitochondrial defects, and could account for the unresponsiveness of kATP to glutamine and leucine stimulus. We therefore tested this hypothesis by supplying pyruvate as the substrate, and again in contrast to the marked increase in mitochondrial kATP in the control cells, there was no change in the mutant cells (Fig. 5A), despite identical increases in oxygen consumption. These results suggest that the DN-HNF-1α mutation results in a significant decrement in mitochondrial function. The identical changes in oxygen consumption indicate that these differences in mitochondrial pyruvate metabolism are not due to differences in pyruvate transport into the cell. As well, the impaired insulin secretory response of the DN-HNF-1α cells when stimulated with methyl pyruvate, which should freely diffuse independent of transporters, supports a mitochondrial deficiency. We also recognized that any observed changes in the pseudo-first order rate constant of ATP synthesis could be due to changes in the concentration of ADP, as well as changes in the catalytic properties of the enzyme. Tandem mass spectroscopic measurements of ADP under these stimulatory conditions found no measurable increase in its concentration and ruled out changes in ADP as a contributing factor to the observed differences. Thus, the combined data support the hypothesis that the deficiency in nutrient stimulation of the mitochondrial ATP synthetic rate constant, kATP, is because of the negative impact of DN-HNF-1α expression upon mitochondrial function.

If we consider that the inherent rate of mitochondrial ATP synthase, as reflected in the magnitude of kATP, is set by the proton motive force across the inner mitochondrial membrane, then these results indicate that exposure to secretagogues increased the mitochondrial proton motive force of the control cells, but not in the mitochondria of the mutant HNF-1α cells. This interpretation agrees well with earlier studies using fluorescent probes showing abrogation of the glucose-induced hyperpolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential in DN-HNF-1α cells (7). ATP synthesis rates were calculated from the rate constant and the intracellular Pi concentration. Addition of all nutrient secretagogues resulted in a rapid and marked decrease in the NMR-observable Pi pool in both the control and dox-treated cells (Fig. 5D). Independently measured rates of ATP synthesis in rat liver using a bioluminescence assay agree well with our NMR-measured rates of ATP synthesis (31). The transfer of the mitochondrial calcium and phosphate to the mitochondria pool and the phosphate buffering of free Ca2+ as the hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) gel could conceivably change the NMR relaxation times and broaden the mitochondrial Pi resonance below the base-line noise. However, tandem mass spectroscopy measurement of total intracellular Pi confirmed the NMR-observed time course of the decrease in the intracellular Pi, in agreement with the reported efflux of Pi from glucose-stimulated rat islets (32). This significant drop in the concentration of intracellular Pi blunted the calculated ATP synthesis rates compared with the changes in the rate constant. Nevertheless, in the control cells, we observed nutrient-stimulated increases in both cytosolic and mitochondrial ATP synthesis rates.

Surprisingly, oxygen consumption rates were similar under all conditions in both the control and dox-treated cells. The robust change in oxygen consumption rates in the DN-HNF-1α cells when supplied with substrates suggests that the Krebs cycle and electron transport are as readily inducible by nutrient supply as the control cells. The blunted changes in ATP synthesis with equivalent oxygen consumption rates indicate a significantly higher degree of mitochondrial uncoupling, and are consistent with an increase in UCP2 activity. Previous studies have shown that changes in UCP2-mediated proton leak manifests primarily as changes in ATP synthesis, rather than substrate oxidation (24, 33). Using metabolic control analysis, Affourtit and Brand (34) showed that in β-cells mitochondrial proton leak is highly responsive to changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential with nutrient stimulation. In addition to glucokinase, proton leak is an important regulator of mitochondrial ATP production and cellular ATP/ADP ratio (34). In the β-cell, mitochondrial proton leak is thought to be mediated mostly through either UCP2 or adenine nucleotide translocase (34). Earlier, Northern blot analysis indicated an up-regulation of UCP2 expression in those cells overexpressing the p291fsinsC mutant of HNF-1α. However, in the HNF-1α-SM6 cells, quantitative RT-PCR was unable to detect any changes in the mRNA expression of either UCP2 or adenine nucleotide translocase after 24 h of dox treatment. An alternative to increased UCP2 concentration would be an increased proton flux through UCP2 activated by the increased production of a mitochondrial factor linked to metabolism. Studies in cells expressing UCP2, including islet β-cells, have shown that superoxide is one such activator of UCP2 (24). To test this possibility, we measured superoxide production in mitochondrial stimulated with pyruvate, and we found that expression of DN-HNF-1α resulted in a 3-fold increase in nutrient-stimulated superoxide production (Fig. 6C). Although these results are suggestive of a mechanism to account for the observed increase in uncoupling activity, a more exhaustive series of studies is needed to definitively prove causality. Regardless of the mechanisms mediating proton leak, the overall effect of the blunted changes in kATP in the HNF-1α mutant cells, combined with a significant and normal efflux of intracellular Pi, resulted in ATP synthesis rates that were refractory to increases in nutrient secretagogues that normally result in increased ATP production. The net result of the decreased rates of ATP synthesis in the mutant HNF-1α cells is reflected in the blunted change in the ATP/ADP ratio with addition of the nutrient secretagogues (Fig. 6D).

Anaplerosis, Pathways and Rates

Although the impaired insulin secretion rates may be due in large measure to the observed deficiencies in ATP production rates, it is now well established that insulin secretion can also be significantly modulated by “second messengers” produced from mitochondrial anaplerosis (11). With the increase in mitochondrial anaplerotic flux, malate, citrate, and in some instances glutamate are exported from the mitochondria. Malate and citrate become substrates for cytosolic enzymes that can cycle them back to the Krebs cycle for entry at the level of either pyruvate or α-ketoglutarate. These cycling pathways result in the net synthesis of cytosolic NADPH, which is suggested to be a required component of several pathways integral to insulin secretion (11). From earlier studies, one of the downstream targets affected by mutant HNF-1α is a decreased expression of oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (7, 8), which should impede overall Krebs cycle flux by limiting synthesis of succinyl-CoA. To assess whether decreased oxoglutarate dehydrogenase expression affected anaplerosis, we used two independent measures of flux through anaplerotic pathways as follows: 1) a 13C NMR isotopomer analysis that provides quantitative measures of the steady-state fluxes relative to Krebs cycle flux; 2) a metabolomics approach to determine initial rates of net synthesis of two of the major products of anaplerosis and the steady-state changes in concentrations.

Despite an increase in relative PDH flux, for both the DN-HNF-1α cells and HNF-1α KO islets upon increasing the glucose from 3 to 15 mm (Fig. 7, A and C), there was no observable change in the relative anaplerotic flux rate (Fig. 7, B and D). However, the initial rate of citrate synthesis and the change in malate and citrate steady-state concentrations (Fig. 8A and Tables 1 and 2) were increased in response to G15, although less than that of the controls. In response to the potent amino acid combination of glutamine and leucine, the 13C NMR isotopomer analysis indicates normal changes in relative anaplerotic flux rates (Fig. 7B) and were reflected in similar increases in the initial rates of malate and citrate synthesis (Table 1), and the change in the steady-state concentrations of citrate and malate (Table 2). These results suggest that the mitochondria from β-cells with DN mutations, or loss of HNF-1α (in islets), were still responsive to changes in extracellular substrate conditions, with appropriate shifts in the mitochondrial metabolic pathways and synthesis of anaplerotic metabolites with glutamine and leucine but not G15.

The decreased anaplerosis rate and steady-state concentrations with G15 may be the result of decreased glycolytic flux; however, the similar OCR in the DN-HNF-1α and control cells suggests a diversion of pyruvate to PDH at the expense of PC flux and anaplerosis. However, in response to glutamine plus leucine, there was no apparent deficiency in mitochondrial anaplerotic rate, or net change in citrate or malate concentrations, for either the stable cell line or the isolated islet. We have previously shown that anaplerosis entry at the level of oxaloacetate (PC) accounts for the majority of anaplerotic flux with G15, whereas when glutamine and leucine are provided, PC and GDH each contribute approximately one-half to the total anaplerotic flux (13, 14). The isotopic distribution in pyruvate was also suggestive of substrate channeling into malate and then into pyruvate when isolated mitochondria were supplied with 13C-labeled glutamate or fumarate (13). In support of this hypothesis, earlier comparison studies on the kinetic regulation of malic enzyme were best explained by hetero-enzyme interactions of ME2 and the PDH complex making ME2-generated pyruvate a better substrate than free pyruvate for PDH (i.e. substrate channeling) (35). The similarity in the anaplerotic responsiveness to glutamine plus leucine also implies that the impaired insulin secretion cannot be explained by deficiencies in amino acid transport (5).

Our metabolomics analysis of the changes in malate, citrate, and aspartate also provides additional insight into our earlier observation that a large proportion of the substrate entering at the level of PC was derived from a source other than the pyruvate derived from exogenous glucose (12, 13). Simpson et al. (36) previously suggested that aspartate could account for this “non-pyruvate carboxylase anaplerosis” and that aspartate flux correlated better with insulin secretion than flux of pyruvate through PC. We found that the initial increases in both the synthesis rates of malate and citrate were matched by identical increases in the disappearance rate of aspartate, and the loss of aspartate could more than account for the combined increased in mass of citrate and malate in response to G15. In response to glutamine plus leucine, however, the initial rate of aspartate disappearance was considerably less than the appearance rates of citrate and malate. This may reflect the mass effect upon GDH flux and enhanced channeling of glutamate to PC under these conditions of high glutamine. Nevertheless, even under these conditions, the steady-state decrease in aspartate concentration was matched by increases in citrate and malate. However, the integrated steady-state anaplerotic flux, as determined by tcacalc, calculates at least an equivalent input to PC from glucose-derived pyruvate. These results suggest that aspartate may be the major source for the generation of mitochondrial second messengers during the first phase of insulin secretion, whereas PC flux of pyruvate is the major contributor to anaplerosis during the sustained second phase. These results also indicate that once steady-state concentrations are reached, there is a net influx of anaplerotic substrates (glucose and/or glutamine) that must be matched by an equivalent disappearance of citrate and malate into other metabolic pools (e.g. lipids and protein) (11, 37).

In summary, we have shown that expression of dominant-negative mutations of the HNF-1α transcription factor in INS-1 cells impairs both glucose- and amino acid-stimulated insulin secretion, in part as the result of mitochondrial dysfunction. Using real time NMR perifusion methodology, we were able to show that the mitochondria from the DN-HNF-1α cells are more uncoupled and less efficient for the synthesis of ATP under conditions of nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion. Additionally, the impaired GSIS in the DN-HNF-1α cells may be attributed in part to a decrease in the net synthesis of mitochondrial second messengers derived from anaplerotic pathways, resulting from the diversion of pyruvate toward oxidation at the expense of the influx of pyruvate and aspartate at the level of oxaloacetate. Anaplerotic pathway analysis, in both the DN-HNF-1α cells and HNF-1α KO islets, also suggests that impaired insulin secretion in response to glutamine plus leucine cannot be attributed to deficiencies in amino acid transport but are likely due to increased uncoupling activity. Thus, mitochondrial defects, as the result of either expression of dominant-negative mutations or loss of HNF-1α, contribute to impaired nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Veronica Fabrizio and Mario Kahn for help with the metabolomic analyses.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK-071071 from USPHS (to G. W. C.). This work was also supported by EuroDia Grant LSHM-CT-2006-518153, a European Community-funded project under Framework Program 6 (to C. B. W.).

3 R. G. Kibbey, personal communication.

- HNF

- hepatic nuclear factor

- AASIS

- amino acid-stimulated insulin secretion

- GSIS

- glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- LC/MS/MS

- high pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- RT

- reverse transcription

- dox

- doxycycline

- DN

- dominant negative

- KO

- knock-out

- PEPCK

- phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- mtPEPCK

- mitochondrial PEPCK

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- PGK

- phosphoglycerate kinase

- PDH

- pyruvate dehydrogenase

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- HMG-CoA

- hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA

- HEt

- hydroethidine

- SAME

- monomethyl succinate

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide 4-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- PC

- pyruvate carboxylase

- OCR

- oxygen consumption rates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fajans S. S. ( 1989) Diabetes Metab. Rev. 5, 579– 606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamagata K., Oda N., Kaisaki P. J., Menzel S., Furuta H., Vaxillaire M., Southam L., Cox R. D., Lathrop G. M., Boriraj V. V., Chen X., Cox N. J., Oda Y., Yano H., Le Beau M. M., Yamada S., Nishigori H., Takeda J., Fajans S. S., Hattersley A. T., Iwasaki N., Hansen T., Pederson O., Polonsky K. S., Bell G. I., et al. ( 1996) Nature 384, 455– 458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pontoglio M., Sreenan S., Roe M., Pugh W., Ostrega D., Doyen A., Pick A. J., Baldwin A., Velho G., Froguel P., Levisetti M., Bonner-Weir S., Bell G. I., Yaniv M., Polonsky K. S. ( 1998) J. Clin. Investig. 101, 2215– 2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dukes I. D., Sreenan S., Roe M. W., Levisetti M., Zhou Y. P., Ostrega D., Bell G. I., Pontoglio M., Yaniv M., Philipson L., Polonsky K. S. ( 1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24457– 24464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih D. Q., Screenan S., Munoz K. N., Philipson L., Pontoglio M., Yaniv M., Polonsky K. S., Stoffel M. ( 2001) Diabetes 50, 2472– 2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas H., Badenberg B., Bulman M., Lemm I., Lausen J., Kind L., Roosen S., Ellard S., Hattersley A. T., Ryffel G. U. ( 2002) Biol. Chem. 383, 1691– 1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H., Antinozzi P. A., Hagenfeldt K. A., Maechler P., Wollheim C. B. ( 2000) EMBO J. 19, 4257– 4264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H., Maechler P., Hagenfeldt K. A., Wollheim C. B. ( 1998) EMBO J. 17, 6701– 6713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagenfeldt-Johansson K. A., Herrera P. L., Wang H., Gjinovci A., Ishihara H., Wollheim C. B. ( 2001) Endocrinology 142, 5311– 5320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamagata K., Nammo T., Moriwaki M., Ihara A., Iizuka K., Yang Q., Satoh T., Li M., Uenaka R., Okita K., Iwahashi H., Zhu Q., Cao Y., Imagawa A., Tochino Y., Hanafusa T., Miyagawa J., Matsuzawa Y. ( 2002) Diabetes 51, 114– 123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald M. J., Fahien L. A., Brown L. J., Hasan N. M., Buss J. D., Kendrick M. A. ( 2005) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 288, E1– 15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malloy C. R., Sherry A. D., Jeffrey F. M. ( 1990) Am. J. Physiol. 259, H987– H995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cline G. W., Lepine R. L., Papas K. K., Kibbey R. G., Shulman G. I. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44370– 44375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pongratz R. L., Kibbey R. G., Shulman G. I., Cline G. W. ( 2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 200– 207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cline G. W., Vidal-Puig A. J., Dufour S., Cadman K. S., Lowell B. B., Shulman G. I. ( 2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20240– 20244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papas K. K., Jarema M. A. C. ( 1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275, E1100– E1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zawalich W. S., Yamazaki H., Zawalich K. C., Cline G. W. ( 2004) J. Endocrinol. 183, 309– 319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abad M. F., Di Benedetto G., Magalhães P. J., Filippin L., Pozzan T. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11521– 11529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiederkehr A., Park K. S., Dupont O., Demaurex N., Pozzan T., Cline G. W., Wollheim C. B. ( 2009) EMBO J. 28, 417– 428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gadian D. G., Radda G. K., Richards R. E., Seeley P. J. ( 1979) Biological Application of Magnetic Resonance ( Shulman R. G. ed) pp. 463– 535, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petroff O. A., Prichard J. W., Behar K. L., Alger J. R., den Hollander J. A., Shulman R. G. ( 1985) Neurology 35, 781– 788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.David G. ( 1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 7495– 7506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papas K. K., Pisania A., Wu H., Weir G. C., Colton C. K. ( 2007) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 98, 1071– 1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krauss S., Zhang C. Y., Scorrano L., Dalgaard L. T., St-Pierre J., Grey S. T., Lowell B. B. ( 2003) J. Clin. Investig. 112, 1831– 1842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]