Distinguishing colonization from infection is an important factor in making the correct diagnosis in a wide variety of paediatric conditions. For example, in this issue of Paediatrics & Child Health, Al-Mutairi and Kirk ( pages 25–30) describe the difficulty in distinguishing bacterial tracheitis from other causes of upper airway obstruction. Part of this difficulty is that growth of bacteria from the trachea can occur because of contamination of specimens by organisms that are colonizing the upper respiratory tract.

Colonization implies that the patient has a sufficiently high concentration of organisms at a site that they can be detected, yet the organism is causing no signs or symptoms. This differs from contamination, where the organism was never present in the site from which it has been detected, but was introduced into the specimen from another site or from contamination in the laboratory. A carrier is a person who is colonized with an organism and may transmit the organism to other people. Colonization can persist for days to years, with resolution influenced by the immune response to the organism, competition at the site from other organisms and, sometimes, use of antimicrobials.

Table 1 summarizes the most common organisms isolated from the respiratory tract and their significance. The most important factor in determining if a patient is colonized or infected with an organism is the clinical picture. For example, in the upper respiratory tract, up to 20% of children are colonized with group A streptococcus (GAS) (1), with the highest concentration of organisms being in the oropharynx. Throat cultures should only be done in children who have symptoms of GAS pharyngitis (sore throat in the absence of cough, rhinitis or laryngitis) because culturing all children with sore throats results in these carriers being treated with antibiotics that will not improve their symptoms. Antibiotics are far less successful in eradicating the organism in the carrier state than in a patient with symptomatic GAS pharyngitis (1); therefore, their use cannot be justified as a measure to reduce transmission of the organism.

TABLE 1.

The most common organisms isolated from the respiratory tract and their significance

| Site of detection | Organism | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Nasal cavity | Staphylococcus aureus |

|

| Oropharynx/nasopharynx | Group A streptococcus |

|

| Group C/G streptococci |

|

|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae |

|

|

| Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis |

|

|

| Neisseria meningitidis |

|

|

| Herpes simplex virus |

|

|

| Candida species |

|

|

| Lower respiratory tract | Group A streptococcus |

|

| S aureus, S pneumoniae |

|

|

| Nontypeable H influenzae, M catarrhalis, and Enterococcus species |

|

|

| N meningitidis |

|

|

| Enterobacteriaceae and nonfermenting Gram-negative bacilli |

|

|

| Herpes simplex virus |

|

|

| Candida species |

|

|

| Aspergillus species |

|

|

| Any respiratory tract site | Viridans group streptococci, Nonhemolyic streptococci, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Nonpathogenic Neisseria species, Corynebacterium species, Lactobacillus species, Micrococcus species, Stomatococcus species, and Bacillus species |

|

| Pneumocystis jiroveci (carinii) |

|

|

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

|

|

| Pasteurella species |

|

|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Bordetella pertussis, adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, coronavirus, human metapneumovirus and rhinovirus |

|

Bacterial pharyngitis in the developed world is usually due to beta-hemolytic streptococci. However, many other organisms can be present in the pharynx. Infants and toddlers commonly become colonized with Streptococcus pneumoniae, nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis and/or Moraxella catarrhalis, with the highest concentration of organisms usually being in the nasopharynx (2). Colonization with these organisms occurs earlier in life if children attend a childcare centre or live in overcrowded conditions (2). Clearance of one serotype of S pneumoniae is often followed by colonization with another serotype, and it has been suggested that children may be colonized with multiple serotypes simultaneously, with the predominant type growing in cultures (3). A small percentage of children will develop invasive disease following colonization with S pneumoniae or N meningitidis. This risk appears to be highest immediately after colonization, likely because the patient has not yet produced antibodies to the organism (2). An inflamed nasopharynx (such as that which occurs with influenza or smoking) may increase the risk of invasive disease following colonization with N meningitidis (4). If a child develops an upper respiratory tract infection while colonized with S pneumoniae, H influenzae or M catarrhalis, they may develop acute otitis media or sinusitis with the colonizing strain. Antibiotics may eradicate the strain, but they may also increase the risk of the child being colonized with a different organism that is resistant to the antibiotic that was chosen (2).

Approximately one-third of adults are persistently colonized with Staphylococcus aureus (5), with the highest concentration of organisms in the respiratory tract being in the nasopharynx. Colonization of the skin and the nasophaynx can occur shortly after birth. Colonization with S aureus precedes most invasive diseases caused by S aureus (osteomyelitis, cellulitis or pneumonia), but such conditions are so rare that eradication could never be justified in an attempt to prevent them. Eradication may be useful in preventing infection of indwelling venous catheters or wound infections in patients undergoing invasive procedures (6). Other possible indications for eradication are if a health care worker is a carrier of methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), or if an MRSA carrier has a chronic severe disease and is therefore likely to spend long periods in strict isolation if they remain colonized. However, the reason to attempt eradication is for infection control purposes, because the risk of invasive disease is very low.

Viruses and fungi can also be detected in the upper respiratory tract. Traditional respiratory viruses (adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus) are almost always pathogens if detected anywhere in the respiratory tract, although they sometimes result in only minor signs or symptoms. Furthermore, there is some evidence that parainfluenza virus can persist for weeks following acute infection (7). Herpes simplex virus can cause stomatitis, but reactivation of this and other herpes viruses, such as Epstein Barr virus and cytomegalovirus, can result in asymptomatic shedding in the pharynx and mouth, which is of no significance. Candida species can be part of normal gastrointestinal flora from mouth to anus, with thrush occuring when the concentration of organisms in the mouth is high. Growth of Candida from the upper respiratory tract usually implies that a sample is contaminated with mouth flora.

It is thought that the lower respiratory tract should be sterile and, therefore, any organism detected there is a pathogen. However, molecular techniques allow for the detection of much lower concentrations of organisms than traditional culture techniques (8), and it may eventually become evident that asymptomatic colonization also occurs in the lower respiratory tract. When attempts are made to obtain samples from the lower respiratory tract, it is always possible for them to be contaminated with organisms that are causing colonization in the upper respiratory tract. Sputum is difficult to obtain from paediatric patients, and adult studies have shown the sensitivity and specificity to be sufficiently low such that some experts recommend obtaining sputum from adults with suspected bacterial pneumonia only in selected circumstances (9). For patients with severe pneumonia, there is no consensus on the relative value of samples obtained by endotracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage or a protected brush specimen (10), but all are superior to sputum. Direct lung aspiration is rarely done but has been described as a useful technique in children with bacterial pneumonia (11). The ultimate way to determine if an organism is a pathogen is to obtain a lung biopsy, because contamination of such specimens is exceedingly rare. However, even that may not confirm a diagnosis if the patient has already received antimicrobials, or if cultures are not requested for the correct organism (such as mycobacteria). One problem with all techniques is that the sensitivity is limited by the fact that the area that is sampled may not be the one with the highest concentration of organisms. However, one basic principle that applies to specimens obtained from all lower respiratory sites is that an organism that is seen on a Gram stain is present in higher concentration than one detected only on culture; therefore, it is more likely to be a pathogen. Also, because polymicrobial lower respiratory tract infections are rare, it is more likely that the true pathogen has been identified if there is heavy growth of a single organism than if there is mixed growth.

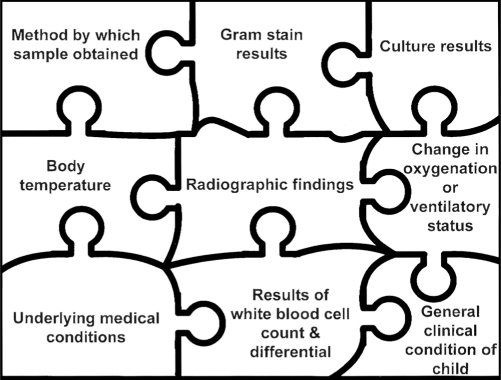

The significance of specific organisms detected in the lower respiratory tract is shown in Table 1. Most of the time, one must put together the pieces of the puzzle that constitute the clinical picture (Figure 1) to determine if antimicrobials should be started.

Figure 1).

Diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infection in the paediatric patient. All the factors shown in the puzzle must be considered in deciding if a child has a lower respiratory tract infection and in choosing antimicrobial agents

The difficulty in detecting anaerobes means that clinicians are seldom faced with determining the significance of these isolates in respiratory tract samples. A more common dilemma is whether to add empiric anaerobic coverage for respiratory tract disease. When proper isolation techniques are employed, anaerobes are isolated from persistent otitis media (12), sinusitis (12), bacterial tracheitis (13) and paediatric pneumonia (14). It remains unclear when anaerobes are pathogens and when they are contaminants or colonizing organisms, but treatment should be considered if they are the predominant organism grown from a sterile or lower respiratory site.

In summary, to determine the significance of an organism isolated from the respiratory tract, one must consider the site from which the organism was isolated, the method of obtaining the sample, the Gram stain results, the other organisms isolated from the same site and, most importantly, the clinical picture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shulman ST, Gerber MA, Tanz RR, Markowitz M. Streptococcal pharyngitis: The case for penicillin therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghaffer F, Friedland IR, McCrackern GH. Dynamics of nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:638–46. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199907000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien KL, Nohynek H, the WHO Pneumococcal Vaccine Trials Carriage Working Group Report from a WHO working group: Standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of. Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:133–40. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000048676.93549.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirsch EA, Barton P, Kitchen L, Giroir BP. Pathophysiology, treatment, and outcome of meningococcemia: A review and recent experience. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:967–79. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doebbeling BN, Breneman DL, Neu HC, et al. Elimination of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriange in health care workers: Analysis of six clinical trials with calcium mupirocin ointment. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:466–74. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bert F, Gladbart J, Zarrouk V, et al. Association between nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and infection in liver transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1295–9. doi: 10.1086/317469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross PA, Green RH, Curnen MGM. Persistent infection with parainfluenza type 3 virus in man. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973;108:894–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.108.4.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murdoch DR. Nucleic acid amplification tests for the diagnosis of pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1162–70. doi: 10.1086/374559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoniou M, Grossman RF. Etiological diagnosis of pneumonia: A goal worth pursuing? Can J Infect Dis. 1995;6:281–3. doi: 10.1155/1995/262169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston BL, Conly JM. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: Where do we go from here? Can J Infect Dis. 2003;14:77–80. doi: 10.1155/2003/581071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vuori-Holopainen E, Peltotla H. Reappraisal of lung tap: Review of an old method for better etiologic diagnosis of childhood pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:715–26. doi: 10.1086/319213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brook I. Antibiotic resistance of oral anaerobic bacteria and their effect on the management of upper respiratory tract and head and neck infections. Semin Respir Infect. 2002;17:195–203. doi: 10.1053/srin.2002.34694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brook I. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of bacterial tracheitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:16–8. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199702000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brook I. Pneumonia in mechanically ventilated children. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:619–22. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]