Abstract

There is growing clinical interest of thalidomide because of its immunomodulatory and antiangiogenic properties, despite its teratogenicity. However, little information about thalidomide has been reported regarding its precise effects on drug-metabolizing enzymes. We investigated the effects of thalidomide on cytochrome P450 (P450) enzymes in human liver microsomes to clarify the potential for possible drug interactions. Thalidomide inhibited S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation activities of recombinant P450 2C19 and human liver microsomes: the apparent concentration of thalidomide producing 50% inhibition was approximately 270 μM for P450 2C19. Midazolam 4-hydroxylation activities were suppressed by thalidomide, but activities of 1′-hydroxylation and total midazolam oxidation and testosterone 6β-hydroxylation were enhanced in the presence of thalidomide. Recombinant P450 3A5 was found to have altered kinetics at clinically relevant concentrations of thalidomide (10–30 μM). P450 3A4 was also affected, but only at higher thalidomide concentrations. Enhanced midazolam hydroxylation by thalidomide was also seen in liver microsomal samples harboring the CYP3A5*1 allele. Similarly enhanced rates of cyclosporine A clearance were observed in P450 3A5 and liver microsomes expressing P450 3A5 in the presence of thalidomide. A proposed effector constant for thalidomide corresponded roughly to its clinical plasma levels. Docking studies with a P450 3A5 homology model, based on the published structure of P450 3A4, revealed close interaction between thalidomide and the heme of P450 3A5. The present results suggest that total midazolam metabolism or cyclosporine A clearance may be increased by thalidomide in a dose-dependent manner. Unexpected drug interactions involving thalidomide might occur via heterotropic cooperativity of polymorphic P450 3A5.

Cytochrome P450 (P450) comprises a superfamily of enzymes involved in the oxidation of a large number of endogenous and exogenous compounds (Guengerich, 2008). In the human liver (HL), P450 3A4 is the major P450 enzyme followed by P450 2C9 (Shimada et al., 1994); however, the importance of polymorphic P450 3A5 in drug oxidations in Asian populations has been recently suggested (Yamaori et al., 2004; Niwa et al., 2008a). P450 2C19 also catalyzes oxidation of many marketed drugs (Williams et al., 2004), but its content in the human liver is relatively low (Inoue et al., 1997). Large interindividual variations in the contents and activities of several P450 forms in human livers lead to different roles for P450s in the oxidations of substrates associated with their pharmacological or toxicological actions (Guengerich, 2008).

Thalidomide [α-(N-phthalimido)glutarimide] had been withdrawn from Europe and Japan in the early 1960s because of its teratogenic effects in humans, but it was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1998 for the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum, an acute inflammatory reaction (Calabrese and Resztak, 1998), and in 2006 for the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma. In Japan, thalidomide was similarly designated for the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma in 2005 as an “orphan” drug (Sembongi et al., 2008), and a decision regarding final approval is expected in 2008. Many clinical trials with thalidomide are ongoing for both anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic activities (Vogelsang et al., 1992; Macpherson et al., 2003; Kamikawa et al., 2006; Breitkreutz and Anderson, 2008). Drug interactions between thalidomide and hormonal contraceptives have only been negative (Trapnell et al., 1998; Teo et al., 2000), and thalidomide has been considered to undergo very little metabolism by the P450 system, at least P450 3A4. However, at least two hydroxylated metabolites of thalidomide have been found in human urine and plasma, both of which could be formed at very low concentrations after incubation with human liver microsomes or recombinant P450 2C19 (Ando et al., 2002). In addition, previous findings have shown spontaneous nonenzymatic hydrolysis (Schumacher et al., 1965). To address the inhibitory potential of a drug, it was considered important to determine an inhibition constant (Ki) (Ito et al., 2004). However, there is little information about inhibition by thalidomide thus far.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the inhibitory potential of thalidomide with human P450 enzymes, to understand possible drug interactions. We investigated the effects of thalidomide on P450 activities and found that thalidomide inhibited P450 2C19-dependent S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation at high concentrations but enhanced P450 3A5-dependent midazolam hydroxylation and cyclosporine A clearance at clinically relevant concentrations. Although there are reports on ligand cooperativity with P450 3A5 (Niwa et al., 2008b), we report a proposed effector constant for thalidomide in the heterotropic cooperativity of P450 3A5 in human liver microsomes, adapting 1 + [I]/Ki treatment theory for drug interaction studies. A proposed model for heterotropic cooperativity of P450 3A5 is presented.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals. (+)-Thalidomide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cyclosporine A and midazolam were obtained from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan). Other chemicals and reagents used in this study were obtained from the sources described previously (Yamazaki et al., 2002, 2006) or were of the highest qualities commercially available.

Enzyme Preparations. Human liver microsomes were prepared in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.10 mM EDTA and 20% (v/v) glycerol as described previously (Yamazaki et al., 2006). The use of the human livers for this study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Vanderbilt University and Showa Pharmaceutical University. Each recombinant human cytochrome P450, coexpressed in Escherichia coli membranes with human NADPH-P450 reductase, was prepared as described earlier (Yamazaki et al., 2002). Genomic DNA samples from livers were genotyped for the CYP2C19 and CYP3A5 genes as described previously (Inoue et al., 1997; Yamaori et al., 2004).

Enzyme Assays. Midazolam 1′- and 4-hydroxylation activities were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (Emoto et al., 2008). Cyclosporine A oxidation was determined by the disappearance of parent compound (Dai et al., 2004). In brief, a typical incubation mixture (total volume of 0.25 ml) contained microsomal protein (0.25 mg/ml) or recombinant P450 (0.06 μM), an NADPH-generating system (0.25 mM NADP+, 2.5 mM glucose 6-phosphate, and 0.25 unit/ml glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase), and substrate and/or thalidomide in 0.10 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), unless otherwise specified. For P450 activity determinations, incubations were performed at 37°C for 10 to 30 min. Incubations were terminated by adding 0.25 ml of ice-cold acetonitrile. The aqueous supernatant was centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min and subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography by using an analytical octadecylsilane (C18) column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm).

Ethoxyresorufin O-deethylation, 7-ethoxycoumarin O-deethylation, diclofenac 4′-hydroxylation, S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation, and testosterone 6β-hydroxylation activities were determined as described previously (Yamazaki et al., 2002). Microsomal protein concentrations were estimated by using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Concentrations of total P450 (Omura and Sato, 1964) and NADPH-P450 reductase (EC 1.6.2.4) (Yamazaki et al., 2002) as well as P450 3A4 and 3A5 contents in liver microsomes (Yamaori et al., 2005) were determined as described previously. The liver microsomal samples HL-1 and HL-3 contained 18 pmol P450 3A4 and 6.1 pmol P450 3A5 per mg of protein and 17 pmol P450 3A4 and 24 pmol P450 3A5 per mg of protein, respectively (Yamaori et al., 2005).

Kinetic Analysis. Kinetic analysis was done using nonlinear regression analysis programs [KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) and Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA)] using the following equations. Inhibition by thalidomide (concentration [I]) of midazolam 4-hydroxylation activity (v) of P450 3A as a function of substrate concentration [S] with a maximum velocity (Vmax) was analyzed for completive inhibition with the usual eqs. 1 and 2:

|

(1) |

and an apparently observed Km value (KmObs), namely (eq. 2)

|

(2) |

where Ki is the inhibition constant (Ito et al., 2004). On the other hand, midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activity (v) shows a substrate-inhibition manner with the eq. 3 formula, including the substrate inhibition constant Ks (Dai et al., 2004):

|

(3) |

When the enzyme activities (v) are increased by thalidomide (concentration [E]), resulting apparent Vmax values multiplied by [1 + [E]/Ke (effector constant)] or deceased KmObs divided by (1 + [E]/Ke) are proposed using the eq. 3 formula. In the present study, apparent Vmax values were not affected, but KmObs values were decreased in the presence of thalidomide; therefore, eqs. 3 and 4, including a novel parameter for effector concentration Ke, were proposed in this study:

|

(4) |

Docking Simulation of Thalidomide into Reported Structure of P450 3A4 and a Homology Model of P450 3A5. The human P450 3A5 primary sequence was aligned with human P450 3A4 (Protein Data Bank code 1TQN) in the MOE software (version 2007.09; Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Canada) for modeling of a three-dimensional structure (Pearson et al., 2007). Before docking, the energy of the P450 3A4 or 3A5 structure was minimized using the CHARM22 force field. Docking simulations were carried out for thalidomide binding to the reported P450 3A4 or a homology model of P450 3A5 using the MMFF94x force field distributed in the MOE Dock software. Twenty solutions were generated for each docking experiment and ranked according to total interaction energy (S value).

Results

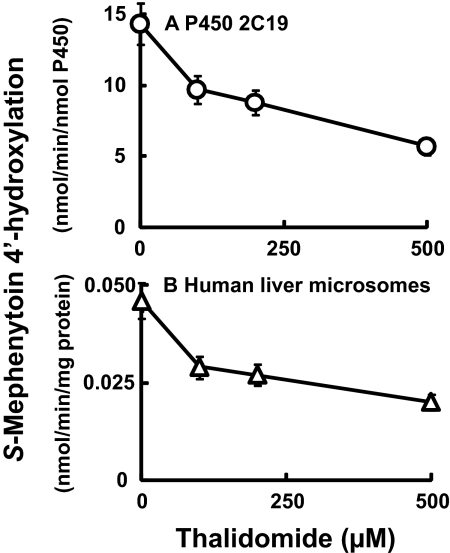

Inhibitory or Enhancing Effects of Thalidomide on Activities of Human P450 Enzymes. Because P450 2C19 has already been shown to be the major enzyme involved in the oxidative metabolism of thalidomide (Ando et al., 2002), we first investigated the inhibitory effects of thalidomide on the typical marker activities of a series of P450 enzymes. The oxidation activities measured with the substrates ethoxyresorufin (10 μM) (recombinant P450 1A1 and 1A2), 7-ethoxycoumarin (100 μM) (recombinant P450 2B6), and diclofenac (50 μM) (recombinant P450 2C9) were not affected by thalidomide (up to 500 μM) under these conditions (results not shown). P450 2C19 S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation activity was suppressed by thalidomide in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A): 50% inhibition was observed with a thalidomide concentration of 270 μM. Similar inhibitory effects of thalidomide on S-mephenytoin hydroxylase activity were seen in liver microsomal preparations (genotyped as CYP2C19*1/*1) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of thalidomide on S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation activity by recombinant P450 2C19 (A) and human liver microsomes (B). S-Mephenytoin (200 μM) was incubated with P450 2C19 and human liver microsomal sample HL-1 (genotyped as CYP2C19*1/*1) in the absence or presence of thalidomide. Results are presented as means and ranges of duplicate determinations.

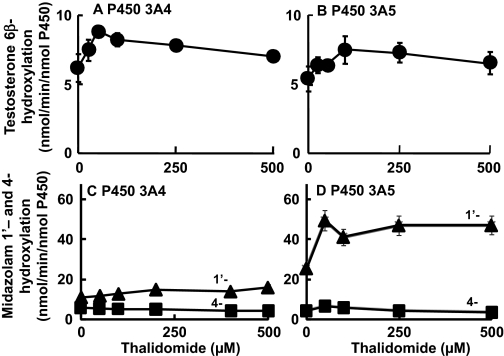

On the contrary, testosterone 6β-hydroxylation (Fig. 2, A and B) by P450 3A4 or P4503A5 was enhanced by thalidomide. Midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activities (Fig. 2D) of P450 3A5 were highly enhanced in the presence of low concentrations of thalidomide. These activities were less affected by thalidomide with P450 3A4 than P450 3A5 (Fig. 2C). The minor pathway, midazolam 4-hyroxylation, was slightly suppressed by thalidomide (with P450 3A4 or 3A5), but rates of formation of the major product (1′-hydroxylation) and total oxidative products of midazolam were stimulated in the presence of thalidomide.

Fig. 2.

Effects of thalidomide on testosterone 6β-hydroxylation activity (•, A and B) and midazolam 1′- (▴) and 4- (▪) hydroxylation activity (C and D) by recombinant P450 3A4 (A and C) and P450 3A5 (B and D). Testosterone or midazolam (100 μM) was incubated with P450 3A4 or 3A5 in the absence or presence of thalidomide. Results are presented as means and ranges of duplicate determinations.

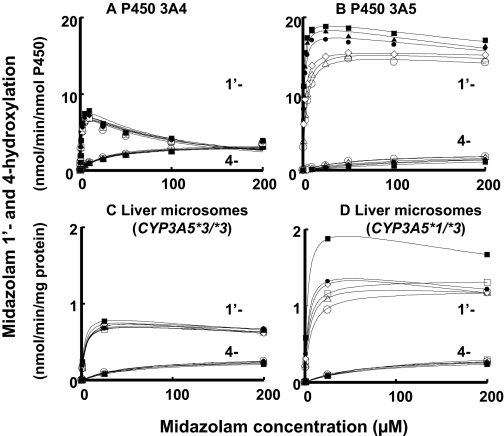

Modifications of Kinetic Parameters for P450 3A-Dependent Drug Oxidation Activities by Thalidomide. It was of interest to describe the enhancing effects of thalidomide in terms of an effector concentration. Midazolam 1′- and 4-hydroxylation activities were plotted against substrate concentrations in the presence of various concentrations of thalidomide (Fig. 3). Only small effects of thalidomide on the midazolam hydroxylation activities of P450 3A4 were observed (Fig. 3A). In the contrast, midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activities of P450 3A5 at low substrate concentrations were enhanced in the presence of thalidomide; however, midazolam 4-hydroxylation was suppressed (Fig. 3B). Human liver microsomes were also used as the enzyme source. The midazolam hydroxylation activities of liver microsomal sample HL-3 (Fig. 3C), genotyped as CYP3A5*3/*3, were not extensively affected, as in the case of recombinant P450 3A4. Midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activities in liver microsomal sample HL-1 (Fig. 3D), genotyped as CYP3A5*1/*3, were also enhanced by the low concentrations of thalidomide.

Fig. 3.

Effects of substrate concentrations (0.25–200 μM) on midazolam 1′- and 4-hydroxylation activity of recombinant P450 3A4 (A) and P450 3A5 (B) and human liver microsomes (C and D) in the absence (○) or presence of 10 (▵), 25 (□), 50 (⋄), 100 (•), 250 (▴), and 500 μM (▪) thalidomide. Human liver samples HL-3 (C) and HL-1 (D) were genotyped as CYP3A5*3/*3 and CYP3A5*1/*3, respectively. Results are presented as means of duplicate determinations.

Apparent Km values (KmObs) for midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activities of P450 3A5 using the Michaelis-Menten equation were reduced from 5.5 μM to 3.0, 1.8, 1.2, 0.97, and 0.77 μM in the presence of 10, 50, 100, 250, and 500 μM thalidomide, respectively (Fig. 3B). We adopted a new parameter, Ke, for modified KmObs vales as Km/(1 + [E]/Ke), in the same way as Ki for Km · (1 + [I]/ Ki) (Table 1). The Ke value of thalidomide enhancement of midazolam 1′-hydroxylation catalyzed by recombinant P450 3A5 was calculated to be 40 ± 7 μM. Similar reduced KmObs values for midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activities by increasing concentrations of thalidomide were obtained in the human liver microsomes expressing P450 3A5 protein (CYP3A5*1/*3): the Ke value was 62 ± 24 μM using the equation of KmObs = Km/(1 + [E]/Ke). In the case of P450 3A4, >10-fold higher Ke values of thalidomide were obtained (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effect of thalidomide on midazolam 1′- and 4-hydroxylation activities of P450 3A4 and 3A5, and human liver microsomes with the kinetic parameter Ke

Kinetic parameters were calculated with nonlinear regression analysis with S.E. values.

|

Enzyme

|

Midazolam Hydroxylation

|

Vmax

|

Midazolam

|

Thalidomide

|

Goodness of Fit, r2

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km, μM | Ks, μM | Ki, μM | Ke, μM | ||||

| nmol/min/nmol P450 | |||||||

| P450 3A4 | 1′- | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 87 ± 10 | 850 ± 370 | 0.98 | |

| 4- | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 25 ± 2 | 1500 ± 620 | 0.99 | |||

| P450 3A5 | 1′- | 18 ± 1 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 1100 ± 200 | 40 ± 7 | 0.98 | |

| 4- | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 59 ± 6 | 160 ± 20 | 0.99 | |||

| nmol/min/mg protein | |||||||

| HL-3 microsomes | 1′- | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 700 ± 100 | 770 ± 300 | 0.98 | |

| (CYP3A5*3/*3) | 4- | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 52 ± 4 | 850 ± 240 | 0.98 | ||

| HL-1 microsomes | 1′- | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 12 ± 3 | 670 ± 290 | 62 ± 24 | 0.94 | |

| (CYP3A5*1/*3) | 4- | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 66 ± 5 | 1100 ± 300 | 0.94 | ||

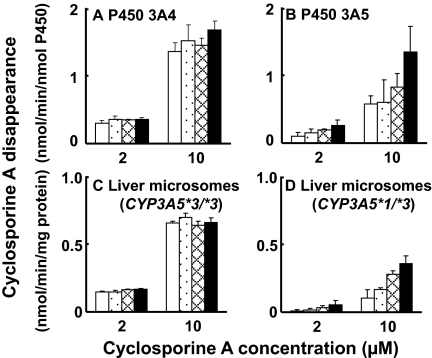

To confirm the enhancing effects of thalidomide on liver microsomal P450 3A5, the oxidation of cyclosporine A was also used as a test reaction (Fig. 4). P450 3A4-catalyzed cyclosporine A oxidation was not affected by thalidomide (Fig. 4A). P450 3A5-catalyzed cyclosporine A oxidation (substrate concentrations of 2 and 10 μM) was enhanced by increasing concentrations (2–30 μM) of thalidomide (Fig. 4B). Similar enhancement of cyclosporine A oxidation by thalidomide was seen in liver microsomes expressing P450 3A5 and 3A4 (Fig. 4D) but not in other liver microsomes mainly expressing P450 3A4 (Fig. 4C). Thalidomide (10–30 μM) enhanced cyclosporine A oxidation mediated by P450 3A5 in human liver microsomes approximately 2-fold.

Fig. 4.

Enhanced cyclosporine oxidation activity with recombinant P450 3A4 (A) and

3A5 (B) and human liver microsomes (C and D) in the absence (□) or

presence of 2 ( ), 10

(

), 10

( ), and 30 μM

(▪) thalidomide. Human liver samples HL-3 (C) and HL-1 (D) were genotyped

for the CYP3A5*3/*3 and CYP3A5*1/*3, respectively. Results

are presented as means ± S.D. from triplicate determinations.

), and 30 μM

(▪) thalidomide. Human liver samples HL-3 (C) and HL-1 (D) were genotyped

for the CYP3A5*3/*3 and CYP3A5*1/*3, respectively. Results

are presented as means ± S.D. from triplicate determinations.

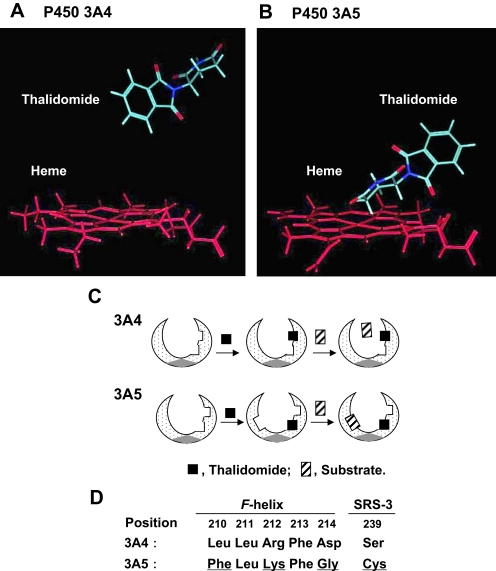

Docking Simulation of Thalidomide into P450s 3A4 and 3A5. The human P450 3A4 crystal structures allowed generation of a homology model of P450 3A5 using the MOE program. The top-rank docking model of thalidomide in P450 3A4 or 3A5 was adopted. In the P450 3A4 model, the aromatic ring of thalidomide was found far from the heme of P450 3A4 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, in the P450 3A5 model, the cycloalkane ring of thalidomide was closely orientated to the center of the heme of P450 3A5 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Docking simulation of thalidomide into a reported structure of P450 3A4 (A) and a homology model of P450 3A5 (B). Thalidomide was docked in orientations with interaction energies (S values) of 38.5 (A) and 38.1 (B), respectively. Proposed working models for heterotropic binding to P450 3A4 and 3A5 (C) and comparison of key amino acid residues in the reported F-helix and SRS-3 between P450 3A4 and P450 3A5 (D) are shown. SRS-3, substrate recognition site-3.

Discussion

In the course of screening the inhibitory potential of thalidomide with human P450 enzymes, thalidomide inhibition of P450 2C19-mediated activity and enhancement of P450 3A activities were seen (Figs. 1 and 2). Thalidomide inhibited P450 2C19-dependent S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation activity only at high concentrations but enhanced P450 3A5-depedent midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activity at low concentrations. P450s 2C9 and 2C19 have both been shown to have a smaller substrate pocket than P450 3A4 (Yano et al., 2004; Locuson and Wahlstrom, 2005; Ahlström and Zamora, 2008). The thalidomide inhibition constant for P450 2C19 was similar to the substrate concentration used for S-mephenytoin. Thus, the active site area of P450 2C19 may be blocked by a similar concentration of thalidomide, resulting in half-maximal inhibition of P450 2C19 function.

Polymorphic P450 3A5s have been suggested to contribute as much as 50% of the liver P450 3A in one third of white and one half of African-Americans (Kuehl et al., 2001; Koch et al., 2002) or Japanese (Yamaori et al., 2004). Because P450 3A5 is 83% identical to P450 3A4, it is generally believed that the substrate specificity of P450 3A5 is similar to that of P450 3A4, although some differences in catalytic properties have been found (Daly, 2006; Niwa et al., 2008a,b). Less activation of P450 3A4 by thalidomide was observed under our conditions. On the other hand, midazolam 4-hydroxylation (minor pathway) was inhibited but 1′-hydroxylation and total disappearance of midazolam (as well as cyclosporine A) were enhanced by thalidomide, presumably mediated via a cooperativity mechanism in P450 3A5 (Figs. 3 and 4). In our preliminary experiments, preincubation of thalidomide with P450 3A5 in the presence of NADPH resulted in decreases in enhanced midazolam 1′-hydroxylation (results not shown), suggesting the involvement of thalidomide itself, not a product (tentatively 5′-hydroxythalidomide), in the activation. Similar activation of P450 3A5-mediated midazolam 1′-hydroxylation was also observed in another liver microsomal sample, HL-130, harboring CYP3A5*1/*3 but not in HL-127 (CYP3A5*3/*3) (results not shown). Because the apparent KmObs values for midazolam 1′-hydroxylation in recombinant P450 3A5 and human liver microsomes were similarly decreased in the presence of thalidomide, the proposed Ke values of thalidomide (approximately 40 μM) for P450 3A5 and liver microsomes are consistent and are one order of magnitude less than those for P450 3A4 (Table 1). These results suggest the hypothesis that thalidomide preferentially binds to P450 3A5. To further address this hypothesis, docking simulations of thalidomide into P450 3A4 and 3A5 models were performed (Fig. 5). Thalidomide could closely dock to the P450 3A5 heme region in silico analysis (Fig. 5B). These results and findings may be collectively relevant to a different preferable substrate orientation for P450 3A5, explaining the P450 3A5 activation.

This activation phenomenon is generally termed heterotropic cooperativity, involving two different ligands in the active site of a P450 enzyme (McConn et al., 2004; Isin and Guengerich, 2006). A proposed model for heterotropic cooperativity of P450 3A5 is shown in Fig. 5C. When thalidomide docks near the heme iron and/or suitable substrate binding area (Roberts and Atkins, 2007; Skopalík et al., 2008), the proposed substrate pocket of P450 3A5 would be affected, resulting in a large active site. On the other hand, because thalidomide apparently does not dock closely to the heme of the P450 3A4 structure (Fig. 5A), the substrate binding area might not be strongly affected (Fig. 5C). This proposed mechanism could be derived from the several differences in reported important amino residues (positions at 210–214) of the F-helix of P450 3A4, remote from the heme of the P450 3A4 catalytic center (Szklarz and Halpert, 1997; Harlow and Halpert, 1998; Fowler et al., 2002), and a characterized Ser239 residue in substrate recognition site-3 (Pearson et al., 2007) (Fig. 5D). The Leu211 residue in both P450 3A4 and 3A5 has been suggested to be an important residue for homotropic cooperativity in P450 3A4 (Szklarz and Halpert, 1997; Harlow and Halpert, 1998; Fowler et al., 2002). Lys212 of P450 3A5 seems to have a similar property, corresponding to Arg212, in P450 3A4 forming the roof of the active site (Harlow and Halpert, 1998). Amino acid differences at positions Leu210, Asp214, and Ser239 in P450 3A4 and Phe210, Gly214, and Cys239 in P450 3A5 might produce a more flexible site and higher lipophilicity in the P450 3A5 active site, to show different phenomena with P450 3A4 for thalidomide. These residues might be key determinant factors for the specificity of thalidomide activation of P450 3A5. Consequently, a thalidomide molecule shifts P450 3A5 into a conformation, such that the proximal binding niche exists near the heme, leading to the stimulation of the cyclosporine and midazolam oxidative activation observed in the present study.

In terms of the clinical consequences of drug interactions with thalidomide, the present results suggest that a more rapid drug clearance might be due to thalidomide via a P450 3A5 contribution. The reported plasma concentrations of thalidomide (Vogelsang et al., 1992) are similar to the proposed Ke constants estimated in the present study. Adapting 1 + [I]/Ki theory to the 1/(1 + [E]/Ke) equation, thalidomide concentrations could reach levels similar to calculated Ke constant and, in principal, approximately 1.5-fold enhanced elimination of other drugs mediated by P450 3A5. We propose the Ke value as a general constant, whereas it is highly likely to be dependent upon an exact pairing of effector and substrate. Vincristine has been reported to be a P450 3A5 substrate (Dennison et al., 2007). Therefore, we investigated interactions between thalidomide and vincristine in vitro. In preliminary experiments, however, low concentrations of thalidomide did not activate the oxidative cleavage of vincristine (catalyzed by P450 3A5 or liver microsomes with CYP3A5*1/*3) (results not shown). The Km values (for the major oxidative cleavage of vincristine catalyzed by P450 3A5) have been reported to be 13 to 17 μM (Dennison et al., 2006). Because vincristine is a large molecule and has high P450 3A5 affinity, these present results may be interpreted that thalidomide could not dock in P450 3A5 before vincristine.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that total midazolam metabolism or cyclosporine clearance may be increased by thalidomide with clinical relevant concentrations through the heterotropic cooperativity of human P450 3A5. Because of the high frequency of polymorphic P450 3A5 expression in Asians and Africans, a relatively high frequency of unexpected drug interactions involving thalidomide might occur via P450 3A5 contribution in drug metabolism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kana Horiuchi and Sachiko Wakiya for assistance.

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan [Grant 17390034]; and the United States Public Health Service [Grants R37 CA090426 and P30 ES000267].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://dmd.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/dmd.108.024679.

ABBREVIATIONS: P450, cytochrome P450; HL, human liver.

References

- Ahlström MM and Zamora I (2008) Characterization of type II ligands in CYP2C9 and CYP3A4. J Med Chem 51 1755–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y, Fuse E, and Figg WD (2002) Thalidomide metabolism by the CYP2C subfamily. Clin Cancer Res 8 1964–1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz I and Anderson KC (2008) Thalidomide in multiple myeloma–clinical trials and aspects of drug metabolism and toxicity. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 4 973–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese L and Resztak K (1998) Thalidomide revisited: pharmacology and clinical applications. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 7 2043–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Iwanaga K, Lin YS, Hebert MF, Davis CL, Huang W, Kharasch ED, and Thummel KE (2004) In vitro metabolism of cyclosporine A by human kidney CYP3A5. Biochem Pharmacol 68 1889–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly AK (2006) Significance of the minor cytochrome P450 3A isoforms. Clin Pharmacokinet 45 13–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison JB, Jones DR, Renbarger JL, and Hall SD (2007) Effect of CYP3A5 expression on vincristine metabolism with human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison JB, Kulanthaivel P, Barbuch RJ, Renbarger JL, Ehlhardt WJ, and Hall SD (2006) Selective metabolism of vincristine in vitro by CYP3A5. Drug Metab Dispos 34 1317–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto C, Murayama N, and Yamazaki H (2008) Effects of phospholipids enzyme sources on midazolam 1′-hydroxylation activity catalyzed by recombinant cytochrome P450 3A4 in combination with NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Drug Metab Lett 2 190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SM, Taylor JM, Friedberg T, Wolf CR, and Riley RJ (2002) CYP3A4 active site volume modification by mutagenesis of leucine 211. Drug Metab Dispos 30 452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP (2008) Cytochrome P450 and chemical toxicology. Chem Res Toxicol 21 70–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow GR and Halpert JR (1998) Analysis of human cytochrome P450 3A4 cooperativity: construction and characterization of a site-directed mutant that displays hyperbolic steroid hydroxylation kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 6636–6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Yamazaki H, Imiya K, Akasaka S, Guengerich FP, and Shimada T (1997) Relationship between CYP2C9 and 2C19 genotypes and tolbutamide methyl hydroxylation and S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation activities in livers of Japanese and Caucasian populations. Pharmacogenetics 7 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isin EM and Guengerich FP (2006) Kinetics and thermodynamics of ligand binding by cytochrome P450 3A4. J Biol Chem 281 9127–9136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Brown HS, and Houston JB (2004) Database analyses for the prediction of in vivo drug-drug interactions from in vitro data. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57 473–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikawa R, Ikawa K, Morikawa N, Asaoku H, Iwato K, and Sasaki A (2006) The pharmacokinetics of low-dose thalidomide in Japanese patients with refractory multiple myeloma. Biol Pharm Bull 29 2331–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch I, Weil R, Wolbold R, Brockmöller J, Hustert E, Burk O, Nuessler A, Neuhaus P, Eichelbaum M, Zanger U, et al. (2002) Interindividual variability and tissue-specificity in the expression of cytochrome P450 3A mRNA. Drug Metab Dispos 30 1108–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl P, Zhang J, Lin Y, Lamba J, Assem M, Schuetz J, Watkins PB, Daly A, Wrighton SA, Hall SD, et al. (2001) Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat Genet 27 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locuson CW and Wahlstrom JL (2005) Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis of cytochromes P450: effect of incorporating higher-affinity ligands and potential new applications. Drug Metab Dispos 33 873–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson GR, Franks M, Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Ando Y, Price DK, and Figg WD (2003) Current status of thalidomide and its role in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 46 (Suppl): S49–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConn DJ II, Lin YS, Allen K, Kunze KL, and Thummel KE (2004) Differences in the inhibition of cytochromes P450 3A4 and 3A5 by metabolite-inhibitor complex-forming drugs. Drug Metab Dispos 32 1083–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa T, Murayama N, Emoto C, and Yamazaki H (2008a) Comparison of kinetic parameters for drug oxidation rates and substrate inhibition potential mediated by cytochrome P450 3A4 and 3A5. Curr Drug Metab 9 20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa T, Murayama N, and Yamazaki H (2008b) Heterotropic cooperativity in oxidation mediated by cytochrome P450. Curr Drug Metab 9 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T and Sato R (1964) The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. I. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J Biol Chem 239 2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JT, Wahlstrom JL, Dickmann LJ, Kumar S, Halpert JR, Wienkers LC, Foti RS, and Rock DA (2007) Differential time-dependent inactivation of P450 3A4 and P450 3A5 by raloxifene: a key role for C239 in quenching reactive intermediates. Chem Res Toxicol 20 1778–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AG and Atkins WM (2007) Energetics of heterotropic cooperativity between α-naphthoflavone and testosterone binding to CYP3A4. Arch Biochem Biophys 463 89–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher H, Smith RL, and Williams RT (1965) The metabolism of thalidomide: the spontaneous hydrolysis of thalidomide in solution. Br J Pharmacol Chemother 25 324–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sembongi K, Tanaka M, Sakurada K, Kobayashi M, Itagaki S, Hirano T, and Iseki K (2008) A new method for determination of both thalidomide enantiomers using HPLC systems. Biol Pharm Bull 31 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, Inui Y, and Guengerich FP (1994) Interindividual variations in human liver cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 270 414–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skopalík J, Anzenbacher P, and Otyepka M (2008) Flexibility of human cytochromes P450: molecular dynamics reveals differences between CYPs 3A4, 2C9, and 2A6, which correlate with their substrate preferences. J Phys Chem B 112 8165–8173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarz GD and Halpert JR (1997) Molecular modeling of cytochrome P450 3A4. J Comput Aided Mol Des 11 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo SK, Sabourin PJ, O'Brien K, Kook KA, and Thomas SD (2000) Metabolism of thalidomide in human microsomes, cloned human cytochrome P-450 isozymes, and Hansen's disease patients. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 14 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell CB, Donahue SR, Collins JM, Flockhart DA, Thacker D, and Abernethy DR (1998) Thalidomide does not alter the pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone. Clin Pharmacol Ther 64 597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelsang GB, Farmer ER, Hess AD, Altamonte V, Beschorner WE, Jabs DA, Corio RL, Levin LS, Colvin OM, and Wingard JR (1992) Thalidomide for the treatment of chronic graft-versushost disease. N Engl J Med 326 1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Hyland R, Jones BC, Smith DA, Hurst S, Goosen TC, Peterkin V, Koup JR, and Ball SE (2004) Drug-drug interactions for UDP-glucuronosyltransferase substrates: a pharmacokinetic explanation for typically observed low exposure (AUCi/AUC) ratios. Drug Metab Dispos 32 1201–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaori S, Yamazaki H, Iwano S, Kiyotani K, Matsumura K, Honda G, Nakagawa K, Ishizaki T, and Kamataki T (2004) CYP3A5 contributes significantly to CYP3A-mediated drug oxidations in liver microsomes from Japanese subjects. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 19 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaori S, Yamazaki H, Iwano S, Kiyotani K, Matsumura K, Saito T, Parkinson A, Nakagawa K, and Kamataki T (2005) Ethnic differences between Japanese and Caucasians in the expression levels of mRNAs for CYP3A4, CYP3A5 and CYP3A7: lack of co-regulation of the expression of CYP3A in Japanese livers. Xenobiotica 35 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Nakamura M, Komatsu T, Ohyama K, Hatanaka N, Asahi S, Shimada N, Guengerich FP, Shimada T, Nakajima M, et al. (2002) Roles of NADPH-P450 reductase and apo- and holo-cytochrome b5 on xenobiotic oxidations catalyzed by 12 recombinant human cytochrome P450s expressed in membranes of Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif 24 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Okayama A, Imai N, Guengerich FP, and Shimizu M (2006) Interindividual variation of cytochrome P450 2J2 expression and catalytic activities in liver microsomes from Japanese and Caucasian populations. Xenobiotica 36 1201–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano JK, Wester MR, Schoch GA, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, and Johnson EF (2004) The structure of human microsomal cytochrome P450 3A4 determined by X-ray crystallography to 2.05-A resolution. J Biol Chem 279 38091–38094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]