Abstract

Patients with atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) with a mutation in the gene encoding membrane cofactor protein (CD46) are known to have a better prognosis than those with mutations in factor H (CFH) or factor I (CFI), but a small number of the former still proceed to end-stage renal failure. Plasma therapy (PE) is the recommended approach to treat both acute episodes and prevent recurrences in aHUS, but studies have yet to show PE efficacy in aHUS associated with a CD46 mutation. The factors determining failure to treatment are not clear and may be related to the mutation involved or to insufficient treatment. Our experience of PE in a family of three sisters with CFH-associated aHUS suggests that intensive and prophylactic PE allows renal function to be maintained in both native kidneys and allografts. The success of this strategy has led us to use it in all cases of aHUS. Here, we describe the effect of this strategy in a child with aHUS and a CD46 mutation. The initial episode was treated with daily PE, resulting in the recovery of renal function. However, over the next 4 years, there was a progressive decline in renal function to end-stage renal failure, with evidence of an on-going thrombotic microangiopathy despite continuous prophylactic PE. Prophylactic PE does not influence the natural course of aHUS and CD46 mutation.

Keywords: Atypical HUS, CD46 mutation, Membrane cofactor protein, Plasma exchange

Introduction

Approximately 60% of patients with atypical haemolytic uremic syndromes (aHUS) have mutations in the genes encoding the complement proteins factor H (CFH), factor I (CFI), membrane cofactor protein (CD46), factor B (CFB) and factor C3 (C3) [1–5]. Among the total number of aHUS patients screened to date for the CFH, CFI and membrane cofactor protein (MCP) mutations, 20% have a mutation of CFH, 15% of MCP and 5–10% of CFI [3]. When patients are stratified according to their underlying mutation, an important “genotype–phenotype” correlation is observed. The prognosis in patients with either a CFH or CFI mutation is poor, with approximately 70% developing end-stage renal failure (ESRF). In contrast, over 80% of patients with a CD46 mutation remain dialysis-independent [1–3]. Although plasma therapy (PE) appears to be beneficial in patients with CFH and CFI mutations, a positive effect in patients with a CD46 mutation is doubtful [2, 3]. In the absence of controlled trials, the analysis of well-documented case reports remains the primary means of assessing the value of PE. To that effect, we have had the unique opportunity to follow over a period of 10 years a family of three sisters (two of whom are monozygotic twins) with CFH-associated aHUS [6]. Analysis of the natural history of the disease in this family suggests that the strategy of plasma therapy is crucial and that only intensive and prophylactic PE are able to maintain renal function in both native kidneys and allografts. The success of this strategy has led us to use it in all cases of aHUS. Here, we describe in this article the effect of this strategy in a child with CD46-associated aHUS.

Case report

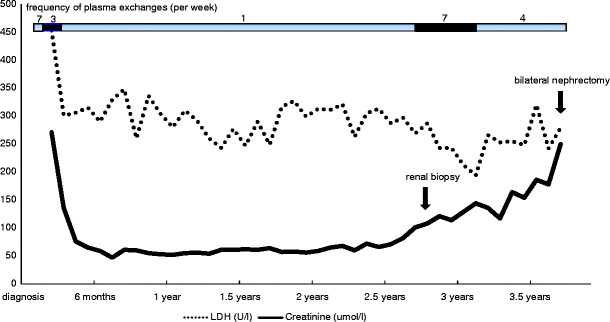

This previously healthy 3-year-old boy presented with renal failure, haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and hypertension in the absence of a preceding diarrhoeal illness. The diagnosis of aHUS was confirmed by renal biopsy, which showed diffuse glomerular basement membrane thickening and splitting with subendothelial fibrinoid deposition. Endothelium swelling associated with wall thickening in some arteries was also visible. Neither glomerulosclerosis nor tubular atrophy was observed. The clinical evolution is outlined in Fig. 1. Dialysis (initially hemodialysis and subsequently peritoneal dialysis) was started because of salt and water retention. The patient was never anuric, and the maximum plasma creatinine level was 270 µmol/L. Dialysis was stopped after 2 months when the plasma creatinine was 110 µmol/L. Two weeks after presentation, the patient developed seizures secondary to malignant hypertension and was admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit where daily PE was commenced (40 ml/kg per session of fresh frozen plasma). After a further 2 weeks, his clinical condition improved, his platelet count normalized and plasma lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) stabilized at slightly increased levels. Eight weeks after presentation, he was transferred to our centre for creation of an arterio-venous shunt and chronic prophylactic PE. The frequency of PE was reduced to three times a week until the plasma creatinine level returned to 47 µmol/L (calculated creatinine clearance according to Schwartz: 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2) 5 months after presentation. The frequency of PE was then reduced to twice weekly and then to once a week thereafter. Of note, the plasma LDH values never normalized completely. The plasma concentration of the complement factors C3, C3d, C4, Factor B, AP 50 and CH 50 were normal and remained so throughout the course of his illness. Growth retardation was present until renal transplantation. Hypertension was difficult to control until the introduction of AII receptors blockers 6 months after presentation. For the next 24 months, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), proteinuria and blood pressure remained normal, and no hospitalization was needed. There were many short episodes of absence which were treated satisfactory with valproic acid and lamotrigine. Computed tomography scanning showed no cerebral lesions. During the third year after presentation, the plasma creatinine level rose progressively from normal values to 127 µmol/L (calculated creatinine clearance 40 ml/min per 1.73 m2). At the same time proteinuria developed (1.1 g/24 h) and the blood pressure increased. The platelet count remained normal despite continuously slightly increased LDH and low haptoglobin plasma values, persisting until nephrectomy. A renal biopsy performed at that time showed extensive global glomerulosclerosis affecting 50% of the glomeruli. The previously mentioned abnormalities persisted in the remaining glomeruli, but arteriolar lesions were more widespread and there was diffuse tubular atrophy. Renal function continued to slowly deteriorate. Four years after initial presentation, the patient was admitted with malignant hypertension (160/105 mmHg), headaches, weight loss and malaise. Because of resistance to antihypertensive therapy and despite the absence of ESRF (plasma creatinine 250 µmol/L), bilateral nephrectomy was performed and hemodialysis was started. There was histological evidence of severe chronic thrombotic microangiopathy in both kidneys. After nephrectomy, blood pressure, plasma LDH and haptoglobin levels normalized, and his general condition improved. Mutation screening of CFH, CFI, C3 and CFB showed no abnormalities. Serum factor H and factor I concentrations were 0.55 g/l (normal range 0.35–0.59 g/l) and 49 mg/l (normal range 38–58 mg/l), respectively. Mutation screening of CD46 showed a missense mutation in exon 11 (c.1058C>T, p.Ala353Val; alternative syntax Ala304Val). The patient was homozygous for the at risk C allele of CD46 c.4047T>C rs7144, heterozygous for the at risk G allele of CD46 -652A>G rs2796267 and homozygous for the at risk G allele of CD46 366A>G rs2796268. He was heterozygous for the at risk T allele of CFH -332C>T rs3753394, heterozygous for the at risk G allele of CFH c.2016A>G Q672Q rs3753396 and heterozygous for the at risk T allele of CFH c.2808G>T E936D rs1065489. At 17 months after starting hemodialysis, he received a cadaver renal transplant. Immunosuppression comprised prednisolone, low-dose cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetyl and basiliximab. Plasma therapy was undertaken immediately prior to transplant, daily during the first postoperative week and then stopped. He did not relapse after transplantation, and the plasma creatinine level 12 months post-transplant is 0.9 mg/dL (80 µmol/L).

Fig. 1.

Effect of prophylactic plasma exchanges in a patient with membrane cofactor protein mutation-related haemolytic uremic syndrome. LDH: lactate dehydrogenase

Discussion

The patient described here was found to have a mutation in the CD46 gene encoding membrane cofactor protein (c.1058C>T, p.Ala353Val). This mutation has been described previously in aHUS and is known to be functionally significant [7]. Of the three aHUS patients described by Fang et al. [7], one developed ESRF. Because MCP is a transmembrane molecule, its role is limited to the surface of endothelial cells, and a CD46 mutation does not lead to systemic complement dysregulation. The clinical implication of a CD46 mutation was analysed in two large series of patients with aHUS [2, 3]. The conclusions drawn from both studies were that CD46 mutations are associated with a less severe course: no patients in the series reached ESRF during the first episode [2], and 86% of patients remained long-term dialysis-free [3]. Also, kidney transplantation was generally successful [2, 3]. No beneficial effect of plasma therapy on the prevention of ESRF could be demonstrated in either series. In the French series [2], favorable outcome occurred in eight (89%) of nine episodes that were treated with plasma therapy and 15 (88%) of 17 untreated episodes; in the Italian series [3], complete or partial remission (defined by healing of hematological symptoms but persistence of renal sequelae) was achieved in 91% of plasma-treated episodes but also in 100% of the non-treated episodes. However, the authors could not exclude that in those patients who did not recover spontaneously, plasma therapy failed because it was not adequately administered. We have previously shown that the success of plasma therapy in aHUS due to a CFH mutation depends on the strategy used. Only intensive PE at presentation followed by prophylactic treatment was efficient in our earlier study [6]. Based on this result, we used a similar approach in the management of this patient with a CD46 mutation. In contrast to many previously reported MCP-associated aHUS patients who have a relapsing course with complete recovery after each relapse, our patient had a single episode, which was unusually severe (prolonged dialysis, severe hypertension) but which resolved completely and was subsequently followed by a progressive deterioration in renal function without any clinical evidence of a significant acute microangiopathy episode (no thrombopenia, no acute hemolytic anemia). The presence of several at risk polymorphisms of CD46 and CFH may have enhanced the pathogenic role of the CD46 mutation on the glomerular endothelium. During the initial presentation, there was a temporal relationship between plasma therapy and an improvement in the clinical condition. However, this improvement was slow, and it is questionable whether this was a result of the treatment or a spontaneous evolution. The delay before the initiation of PE may have eventually played a role in this slow recovery. Subsequently, regular prophylactic PE was unable to prevent the development of ESRF despite intensification in the frequency of PE from weekly to daily. It is probable that ongoing low-grade chronic thrombotic microangiopathy, as evidenced by continuously slightly increased plasma LDH plasma levels and a low haptoglobin until the time of nephrectomy, had a significant role in the progression to ESRF. The response to PE in this patient is, therefore, in keeping with the suggestion from the authors of the two previous studies [2, 3], that plasma therapy is unlikely to be of therapeutic benefit in CD46 mutation-associated aHUS, at least when given preventively. However, because the results of mutation screening of complement genes are not available for weeks or months after presentation, all patients who present with aHUS should be treated with PE. When the results of the mutation screening eventually become known, these can guide both the PE strategy to prevent relapses and the approach to transplantation if and when patients reach ESRF—but clear-cut recommendation concerning the treatment of relapses cannot be given here.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Kavanagh D, Goodship TH, Richards A. Atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome. Br Med Bull. 2006;77–78:1–18. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sellier-Leclerc AL, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Dragon-Durey MA, Macher MA, Niaudet P, Guest G, Boudaullez B, Bouissou F, Deschenes G, Gie S, Tsimaratos M, Fischbach M, Morin D, Nivet H, Alberti C, Loirat C. Differential impact of complement mutations on clinical characteristics in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2392–2400. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caprioli J, Noris M, Brioschi S, Pianetti G, Castelletti F, Bettinaglio P, Mele C, Bresin E, Cassis L, Gamba S, Porrati F, Bucchioni S, Monteferrante G, Fang CJ, Liszewski MK, Kavanagh D, Atkinson JP, Remuzzi G. Genetics of HUS: the impact of MCP, CFH and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood. 2006;108:1267–1279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-007252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goicoechea de Jorge E, Harris CL, Esparza-Gordillo J, Carreras L, Arranz EA, Garrido CA, López-Trascasa M, Sánchez-Corral P, Morgan BP, Rodríguez de Córdoba S. Gain-of-function mutations in complement factor B are associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:240–245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603420103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Regnier C, Blouin J, Dragon-Durey MA, Fridman WH, Janssen B, Loirat C. Protective or aggressive: Paradoxical role of C3 in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:172. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.07.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davin JC, Strain L, Goodship TH. Plasma therapy in atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome: lessons from a family with a factor H mutation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1517–1521. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0833-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang CJ, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Liszewski MK, Pianetti G, Noris M, Goodship TH, Atkinson JP. Membrane cofactor protein mutations in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), fatal Stx-HUS, C3 glomerulonephritis, and the HELLP syndrome. Blood. 2008;111:624–632. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]