Abstract

Preschoolers made numerical comparisons between sets with varying degrees of shared surface similarity. When surface similarity was pitted against numerical equivalence (i.e., crossmapping), children made fewer number matches than when surface similarity was neutral (i.e, all sets contained the same objects). Only children who understood the number words for the target sets performed above chance in the crossmapping condition. These findings are consistent with previous research on children’s non-numerical comparisons (e.g., Rattermann & Gentner, 1998; Smith, 1993) and suggest that the same mechanisms may underlie numerical development.

A large part of learning any concept involves recognizing equivalencies. Understanding the notion of “dog” depends on recognizing that different examples of dogs are alike—they are all members of the dog category, despite their many differences. Number can be viewed the same way. To understand the notion of “two,” children must recognize that different sets of two are alike in terms of numerosity, despite differences along a variety of non-numerical dimensions.

From this perspective, it is natural to think that number concepts are constructed using the same mechanisms as other concepts, such as object categories, colors, textures, and so forth. However, this possibility has not been explored in previous work because number is often seen as a special case. One reason is that number concepts have unique properties. Number is not an object or an attribute of objects. It is an attribute of groups. This makes it difficult to point out the two in a scene as easily as one might point out the dog. Furthermore, number categories ride on the back of other categories. A dog is a dog, but two can only be two in reference to some other grouping (e.g., two cups, two dishes, two colors, etc.). Finally, number words are unique. They not only label set size, like other words label objects, but also are elements in an ordered sequence.

Another reason number development is seen as exceptional is that research on early number learning has tended to emphasize domain specific processes (e.g., Gelman, 1991; Wynn, 1995). This perspective is based on studies indicating that even young infants have numerical sensitivity. The apparent early emergence of number concepts led some to conclude that there is an inborn enumeration process—one that not only provides a way to represent different numbers of items, but also orients attention toward number and facilitates numerical comparisons by ignoring non-numerical details (e.g., the objects’ sizes, colors, textures, etc.).

From this perspective, the potential role of categorization processes in early childhood might not seem obvious. Indeed, if babies can represent and compare sets, it seems that children should have little trouble recognizing numerical equivalence in the first place. However, this conclusion would be premature. First, previous research indicates that children do have trouble recognizing numerical equivalence (Mix, 1999a, 1999b, in press; Mix, Huttenlocher & Levine, 1996; Siegel, 1973). Second, the domain specific accounts are based on evidence from infants that has, itself, been called into question. For example, in the stimulus materials used with infants, number has often been confounded with other quantitative variables, such as contour length. Thus, it is possible that infants in these experiments responded to changes in non-numerical variables, rather than changes in number per se (see Mix, Huttenlocher & Levine, 2002, for a review). But even if there is a domain specific component to number learning, domain general processes of categorization still could play an important role. For example, Gelman (1993) has argued that although inborn processes might represent the principles of a domain, such as number, they could do so implicitly, via the structure of the information processing mechanisms themselves. Thus, inborn enumeration might implicitly represent equivalence because of the way it operates, but this representation is not necessarily accessible by the infant. If so, explicit numerical equivalence groupings may still be constructed in early childhood, and a significant part of this construction could depend on domain general processes.

The Role of High Similarity in Conceptual Development

Research on children’s comparisons has identified several mechanisms of conceptual growth that seem to underlie categorization in general, and may underlie numerical development as well. One mechanism involves high similarity comparisons. It is thought that when items share many commonalities, there are more ways to align them and thus, more reasons to initiate a comparison. In other words, high similarity functions as an invitation to compare (e.g., Rattermann & Gentner, 1991). This is important because, on this view, new dimensions of similarity are discovered in the course of comparing along known dimensions.

To illustrate, consider how non-color comparisons could promote learning about color. Children who encounter two objects with only one attribute in common, such as a red apple and a red truck, have little reason to consider how the objects are similar unless they already have a concept of “red” or “same color.” But if the items have many shared attributes (e.g., two red apples) there are many dimensions of similarity that could capture children’s attention and invite further analysis. Once children start to align the objects for whatever reason, they are likely to discover new ways of comparing them, including same color. In this way, experience with high similarity comparisons is thought to build new conceptual structures and these developing structures, in turn, lead to more abstract and detailed comparisons.

Consistent with this, several studies have demonstrated that experience with high similarity comparisons helps children recognize less obvious relations in subsequent, low similarity comparisons (Klibanoff & Waxman, 1999; Kotovsky & Gentner, 1996; Marzolf & DeLoache, 1994). For example, Kotovsky and Gentner (1996) found that 4-year-olds had great difficulty recognizing the relation between circles that increased in size and squares that increased in darkness. However, when children were trained on same-dimension comparisons (e.g., sets that all increased in size), their performance on cross-dimension comparisons improved significantly.

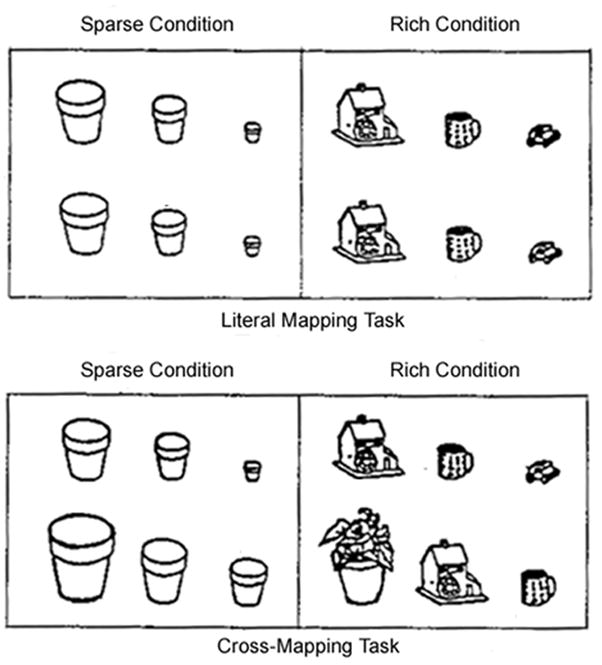

Furthermore, young children often fail to recognize similarity unless there is a high degree of featural overlap between the items (Brown & Kane, 1986; Deloache, 1989; Smith, 1984, 1993; Gentner & Rattermann, 1991; Gentner & Toupin, 1986; Holyoak, Junn, & Billman, 1984). In fact, young children’s reliance on overall similarity is so strong that when underlying relations are pitted against shared surface features, they tend to choose the latter. Rattermann, Gentner, and Deloache (1987, 1989) obtained this pattern using a test of relative size matching. Children were asked to find a sticker hidden under one of three objects in one array, after watching an experimenter hide the sticker in an analogous location in another array (see Figure 1). For example, if the experimenter hid the sticker under the medium sized object in an array containing a coffee cup, a car, and a potted flower, the child’s sticker could be found under the medium sized object in an array containing a car, a potted flower, and a toy house. However, this arrangement created a crossmapping between the two arrays where the identity match (i.e., the two cars) was pitted against the size match (i.e., the two medium sized items). Preschoolers were profoundly affected by this manipulation—they performed at chance in this task until 4 years of age and did not approach ceiling until age 5. This, of course, makes sense if there is an advantage to high similarity comparisons for children who have not learned many relations.

Figure 1.

Rattermann et al.’s (1987, 1989) relational matching tasks.

The Role of Shared Labels in Conceptual Development

A second general-purpose mechanism of category learning involves shared labels. It is well established that children are more likely to match items with the same name (Imai, Gentner, & Uchida, 1994; Markman, 1989; Rattermann & Gentner, 1998; Waxman & Hall, 1993; Waxman & Markow, 1995). For example, in the sticker search task described above, children made more relational matches when the different sized items were labeled, “Baby, Mommy, Daddy” (Rattermann & Gentner, 1998). Thus, in the crossmapping task, the two medium sized items would have been called “Mommy” even though the actual items were completely different. Given these labels, 3-year-olds’ performance improved dramatically from chance levels to near ceiling (i.e., 89%). In fact, the presence of shared labels was so strong in this task that it eliminated the previous age difference (i.e., 3-year-olds with label training performed as well as 5-year-olds without label training).

Matches involving shared labels are thought to promote the discovery of new dimensions in two ways. First, shared labels signal that there is a commonality (Rattermann & Gentner, 1998; Sandhofer & Smith, 1999; Smith, 1993; Waxman & Markow, 1995). Thus, like shared surface features, a shared label can initiate comparisons that are themselves a means of discovering new dimensions. Second, shared labels can direct attention toward a particular dimension (Smith, 1993). For example, the word, “red,” can orient children toward the dimension of color and help them filter out information about non-color attributes.

Do These Mechanisms Underlie Numerical Development?

Existing research on children’s numerical equivalence judgments already suggests parallels between numerical and non-numerical comparisons. When asked to choose the numerically equivalent sets in a triad task, preschoolers perform significantly better when the surface similarity between sets is high (Mix, 1999a, 1999b, in press; Mix, Huttenlocher & Levine, 1996). For example, Mix (1999b) found that across preschool age, children recognized numerical equivalence more easily when comparing nearly identical sets (i.e., black disks and black dots) than when comparing object sets with only number in common (i.e., red pasta shells and black dots). Furthermore, cross-sectional comparisons indicate that competence on low similarity comparisons emerges later than on high similarity comparisons. This pattern echoes the high-to-low similarity shift that has been observed repeatedly in the development of children’s comparisons (e.g., Gentner, 1988; Smith, 1989).

Existing research also indicates that children who demonstrate at least some understanding of the verbal counting system also recognize more numerical matches (Mix, 1999a, 1999b, in press; Mix et al., 1996). In fact, children who lacked even a minimal level of counting ability (i.e., those who could not count to two or produce sets of one and two on demand), failed every test of numerical equivalence except for the condition involving nearly identical sets.

These findings hint that the same surface similarity and labeling effects observed across domains are present in numerical comparisons. If so, perhaps the same learning mechanisms are involved. However, while these findings suggest parallels at a general level, they do not provide direct evidence of particular effects, such as the crossmapping effect reported by Rattermann and Gentner (1998). Furthermore, whereas the influence of counting skill on number matching is consistent with a role for number labels, the skills of counting sets and labeling sets are not conceptually interchangeable. Indeed, these two skills appear to develop separately until age 4 years (e.g., Fuson, 1988; Wynn, 1992). To determine whether labeling per se plays a role in numerical categorization, it would be preferable to examine knowledge of number labels in isolation from counting.

The present study addresses these issues. Children completed a triad matching task in which they viewed a standard set and then pointed out the numerically equivalent set from among three alternatives, one of which crossmapped surface similarity with numerical equivalence. Performance was examined with respect to children’s ability to verbally label the target set sizes (i.e., correctly interpret the count words, “two,” “three,” and “four”), independent of their ability to count these sets.

Method

Participants

Sixty-four children participated in the experiment. They were divided evenly into four age groups (years-months): 3-1/2-year-olds (mean age 3–6; range 3-0 to 3–11); 4-year-olds (mean age 4-3; range 4-0 to 4–5); 4-1/2-year-olds (mean age 4–8; range 4–6 to 4–11); and 5-year-olds (mean age 5-3; range 5-0 to 5–8). Each age group included roughly the same number of boys and girls. Children were drawn from a mixed but predominantly white, middle class population, and all came from homes where English was the primary language.

Materials and procedure

Each child completed two matching tasks followed by the give-a-number task used to assess knowledge of the count words. On each trial of the matching task, a display with the target number of stickers (either two, three, or four) was presented and the child chose an equivalent display from among three choices. These target numerosities were chosen for several reasons. First, this is the range of set sizes for which young children have performed well on nonverbal tasks (e.g., Huttenlocher, Jordan & Levine, 1994; Mix et al., 1996). Moreover, it is possible for children to determine the cardinality of these set sizes without counting or understanding the cardinal word principle (Wynn, 1990, 1992). Thus, verbal counting is not required, in principle, to demonstrate an understanding of numerical equivalence for these sets. Also, using these set sizes permitted direct comparison with previous studies using the same task (e.g., Mix, 1999a, 1999b, in press, Mix et al., 1996).

In most previous work using this procedure, the target sets were hidden before the choice cards were revealed (Mix., 1999a, 1999b; Mix et al., 1996). This was done to parallel the memory demands of other conditions involving sequential sets. However, the aim of the present experiment was to test sensitivity to non-numerical surface features, not memory for number. Therefore, the target sets were left in full view while children made their choices. This was not expected to impact the results, because the surface similarity effects reported previously for hidden sets have been replicated for sets left in full view (Mix, in press). The present study simply extends that finding to a potentially more disruptive relation between surface features and numerical equivalence (i.e., crossmapping).

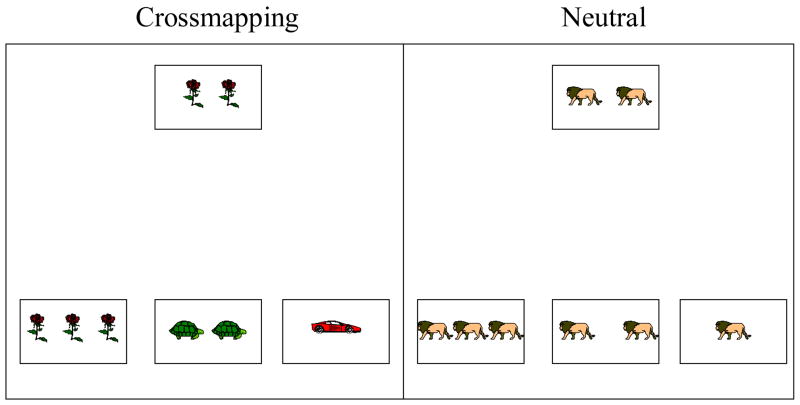

Both the target and choice displays were constructed from 5 by 8 inch, unlined, white index cards. Each choice card contained a homogeneous set of stickers, ranging in number from one to five, that were richly detailed photographs of familiar items, such as animals, foods, vehicles, and flowers. The two matching conditions differed in terms of the foils (see Figure 2). In the crossmapping condition, one of the foil cards was an object level match. It contained a different number of items than the target card, but the stickers on one card were a subset of the stickers on the other. The other foil differed from the target card in terms of both number and the particular stickers used. This foil was included to detect random guessing. In the neutral condition, all three choices had the same stickers as the target card but varied in total number. This condition paralleled the task demands of previous research demonstrating that 3-year-olds can match identical sets (e.g., Mix, 1999a, 1999b; Mix et al., 1996), but used complex pictures rather than black dots.

Figure 2.

Sample crossmapping and neutral trials.

The foils in both conditions were constructed so that on one-third of the trials, the numerically equivalent choice was either the largest in number, the smallest in number, or in the middle compared to the other two choices. The matching tasks were presented in one of two counterbalanced orders (crossmapping first or neutral first). The twelve trials for each condition were presented in one of two fixed random orders.

The stickers were arranged in lines. On half of the trials, the linear arrays on the choice cards were equated for length. On the other half, the arrays were equated for density. Children were prevented from matching the sets in terms of line length because the linear arrays on the target cards were always presented in the alternate format. That is, on trials for which the choice cards were matched for line length, the elements in the target set were spaced apart as they would be on a triad of density-controlled cards. Similarly, when choice cards were equated for density, the elements in the target set were spaced apart as they would be in a triad of line length-controlled cards. Singletons appeared as foils on two of the twelve test trials. These stickers were always centered on the card. The position of the number match relative to the other choice cards was counterbalanced across trials so that it appeared on in all three positions equally often. To allow the experimenter to present all three choice cards simultaneously, the cards for each trial were attached to a 27.5 by 5 inch piece of black poster board using hook and loop tape (i.e., Velcro).

Matching trials began with the rows of choice displays placed face down in front of the child. The cards with the target sets also were placed face down between the experimenter and the choice displays. On each trial, a target display was turned over and left in full view of the child for a few seconds. Next, with the target set still in full view, the first set of choice cards was turned over to reveal the three sets of stickers. Children indicated their choices by pointing. By presenting all of the cards simultaneously, children were not required to remember the numerosity of the target set. Thus, this experiment was a pure test of their ability to recognize numerical equivalence.

The task was introduced with a brief series of familiarization trials using target displays of one and two. The familiarization procedure was based on that used in previous work (Kotovsky & Gentner, 1996; Mix, 1999a, 1999b; Mix et al., 1996). First the experimenter said, “We’re going to play a game. I’ll show you how it goes.” Then, she demonstrated the task by presenting a target set and pointing to the numerically equivalent choice card while saying, “See? This card goes with this card.” The child was told, “Now it’s your turn” and received two practice trials—one with the target set just used in the demonstration and another with a different target set but the same three choice cards. This sequence was then repeated with new target sets and choice cards. In one set of familiarization trials, the objects pictured on the target and choice cards were the same, like the test trials in the neutral condition. In the other set of familiarization trials, the objects pictured on the target and choice cards varied, like the test trials in the crossmapping condition. All children received both sets of familiarization trials. The order of presentation was randomized across children. During the practice trials, children were told whether or not their responses were correct. When children were correct, the experimenter said, “Right! That card goes with this card. Good job!” When children were incorrect, the experimenter said, “Nope, it’s not that card. This card goes with this card” while pointing to the correct choice. Children were encouraged to point with the experimenter and when they did, the experimenter said, “Right! That’s the card that goes with this card. Good job!” No feedback was given during test trials.

In the give-a-number task, children were given fifteen disks and asked to place a certain number of them on a blank index card. Each of the numbers from one to six was requested in one of two fixed random orders. After each response, the disks were returned so that the pile of fifteen disks remained constant across trials. The range of numerosities requested is based on Wynn’s (1990) procedure.

Results

The proportion of correct numerical matches given by children at different ages in the two conditions is presented in Table 1. These scores were submitted to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with age and condition order (crossmapping first vs. neutral first) as between-subjects variables. There were no significant effects involving order. However, there were significant main effects of both condition (F (1, 56) = 44.57, p < .0001, Cohen’s d = 1.19) and age (F (3, 56) = 5.04, p < .005, Cohen’s d = .40). Overall, children performed significantly worse on the crossmapping version of the task than they did on the neutral version (crossmapping: M = .54, SD = .32; neutral: M = .80, SD = .20). Paired t-tests revealed that the main effect of age was due to significantly lower scores for the 3-1/2-year-olds versus the other three age groups (all p’s < .05). The differences between the 5-year-olds and both 4- and 4-1/2-year-olds approached significance (both p’s < .10). The scores of 4- and 4-1/2-year-olds did not differ (p > .97).

Table 1.

Proportion of Number Matches by Age and Condition, Experiment 1

| Crossmapping | Neutral | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (N = 16) | Proportion of number matches (SD) | t | Proportion of number matches (SD) | t |

| 3-1/2 years | .32 (.25) | −.17 | .74 (.17) | 10.25a |

| 4 years | .55 (.31) | 2.75a | .80 (.22) | 7.83a |

| 4-1/2 years | .55 (.30) | 2.75a | .80 (.24) | 7.83a |

| 5 years | .76 (.28) | 6.14a | .85 (.17) | 13.00a |

The percentage of number matches is significantly greater than chance (.33) based on two-tailed t-tests, p < .05.

The ANOVA also revealed a significant interaction between age and condition (F (3, 56) = 3.11, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .31). Simple effects tests indicated that this was due to two factors. First, performance only differed as a function of age in the crossmapping condition (F (3, 60) = 6.41, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .45). There was no age effect for the neutral scores (F (3, 60) = 0.80, p > .50, Cohen’s d = .16). This finding parallels previous reports that children this age can recognize numerical equivalence when the sets are identical and the foils contain similar items (Mix, 1999a, 1999b; Mix et al., 1996). Second, children in the three younger age groups had significantly lower scores in the crossmapping task versus than in the neutral task (all p’s < .01). In fact, 3-1/2-year-olds performed at chance in the crossmapping condition even though their scores in the neutral version were significantly greater than chance (see Table 1). This gap in performance did not close until five years of age, when the difference between conditions was no longer significant (F (1, 15) = 1.43, p > .20, Cohen’s d = .14).

The distribution of children’s errors in the crossmapping condition is presented in Table 2. Recall that, in addition to the numerical match, children had the option of choosing either a high similarity object match or a non-match. Those who chose the number match on at least eight trials (i.e., p < .05 based on a binomial distribution) were considered number matchers. Similarly, those who chose the object match on at least eight trials were considered object matchers. All other children were considered random guessers.

Table 2.

Distribution of Children’s Number Responses and Errors at Different Ages

| Age group | Number (proportion) of number matchersa | Number (proportion) of object matchersa | Number (proportion) of random guessers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1/2 years (N = 16) | 4 (.25) | 5 (.31) | 7 (.44) |

| 4 years (N = 32) | 17 (.53) | 4 (.13) | 11 (.34) |

| 5 years (N = 16) | 13 (.81) | 1 (.06) | 2 (.13) |

Includes children who chose this match on at least 8/12 trials (p < .05, binomial distribution)

A considerable number of children chose the object match, particularly in the younger age groups. This was true even though they had been shown the number match on the demonstration trials, and had gone on to correctly identify the number match in the neutral condition. Of the 30 children who were not consistent number matchers, 33% (or 10 children) systematically chose the object match in error, rather than exhibiting a general failure on the crossmapping task. Thus, there was a strong pull to match on the basis of surface features and object level similarity rather than the less obvious property of number.

Still, this was not always the case. The majority of children who failed to recognize numerical equivalence performed randomly (i.e., 67%). Apparently, some children did not recognize the number match, yet realized that the object match was incorrect. This might have happened because the object foil, though highly similar, was not an exact match. Children may have concluded that none of the cards matched the standard. There also may be a developmental component, whereby children experience a period of disequilibrium between rejecting the object match and recognizing the number match. This could explain why a higher proportion (67%) of erring 4-year-olds performed randomly than did erring 3-year-olds (50%). Finally, it is worth noting that similar patterns have been reported in previous research involving crossmapping (Rattermann & Gentner, 1998). In particular, 3-1/2-year-olds performed at chance in the crossmapping version of the sticker search task described earlier rather than performing below chance, as one might expect if they were consistently making object based matches.

Without a clear preference for the object match, it is hard to know whether the relative difficulty of the crossmapping condition reflects (1) the distracting presence of the object match, (2) the level of similarity between items in the numerically equivalent sets compared to same sets in the neutral condition (i.e., the crossmapping number match is low in similarlity whereas the neutral number match is high), or both. Certainly, the low similarity of the number match contributed to the difficulty of the crossmapping task. However, previous work with non-identical number matches suggests there is more to it than that. Using a parallel task, Mix (1999b; 2002) asked children to match an object set to a numerically equivalent set of black dots. When the objects were toy lions or pasta shells painted red—that is, objects that bore little similarity to the black dots—children performed worse than when the objects and dots were highly similar. Nonetheless, they exceeded chance levels at younger ages than children in the present crossmapping condition (3-1/2 vs. 4 years, respectively). This indicates that the crossmapping condition has additional challenges, above and beyond the fact that the matching sets are low in similarity.

As noted in the introduction, children have performed better on matching tasks when the attributes being compared were labeled (e.g., Rattermann & Gentner, 1998). To see whether similar effects improve performance on the present task, the data were next analyzed with respect to label knowledge. Because research on categorization has emphasized the use of labels per se, these analyses focused on whether or not children already understood the labels for the target set sizes used in this experiment rather than their general ability to count. In other words, did children perform better on the crossmapping task if they understood the meanings of the words, “two” “three” and “four,” irrespective of their other counting skills? This approach does not rule out the possibility that children counted in this task. Indeed, some may have used counting to determine the cardinality of the sets. However, previous research suggests that acquisition of the small number words develops independent of counting skill (i.e., children can name sets of two, three, and perhaps four without counting). Measuring only label knowledge ensured that children who knew these words were not excluded due to poor counting performance.

Children’s understanding of these count word labels was assessed using their give-a-number performance. In this task, children were asked to produce set sizes using disks (e.g., “Please put three disks on this card.”). Children received one point for each count word — “two”, “three”, and “four”—they accurately interpreted, up to a total of three possible points. To simplify the analysis, children were grouped into proficient and non-proficient labeling groups. Children in the proficient group demonstrated knowledge of at least two of the three labels. This criterion was chosen because, if knowing the set size labels improves performance, knowing just two would be sufficient to support above chance performance (i.e., 8/12 trials correct). Children in the non-proficient group demonstrated knowledge of one or fewer of the labels. These two groups were further divided based on their actual crossmapping scores—those who performed significantly above chance (i.e., matched on number at least 8 of the 12 trials, p < .05, binomial distribution) and those who did not.

The total number of children in each of the resulting four groups is presented in Table 3. Among the children who were not proficient labelers, only one performed the crossmapping task above chance. The rest (92%) performed randomly. Many of the children who were proficient labelers also performed well on the crossmapping task, but the majority (57%) still performed at chance. A Fisher’s exact test confirmed that this pattern was significantly different from the pattern expected by chance (p < .05). These findings indicate that knowledge of the small count labels is not sufficient for recognizing numerical equivalence on the crossmapping task, but it may be necessary.

Table 3.

Children’s Performance on the Crossmapping Task Based on Level of Count Word Knowledge

| Count word knowledge | ||

|---|---|---|

| Crossmapping performance | Not proficient | Proficient |

| At or below chance | 12 | 29 |

| Above chance | 1 | 22 |

An ANOVA was conducted on children’s matching scores (i.e., the percentage of number matches) in the two conditions (Crossmapping and Neutral) with labeling proficiency as the between-subjects variable. There was a significant main effect of labeling proficiency (F(1, 62) = 12.86, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .64), such that proficient labelers performed better on both matching tasks (proficient labelers: M = .72, SD = .28; non-proficient labelers: M = .49, SD = .29). The interaction between labeling proficiency and matching condition did not reach significance (F(1, 62) = 1.44, p < .25, Cohen’s d = .21). However, only the proficient labelers performed above chance in both conditions (neutral: M = .83, SD = .18, t (50) = 16.67, p < .0001, Cohen’s d = 2.77; crossmapping: M = .60, SD = .31, t (50) = 6.75, p < .0001, Cohen’s d = .86). In contrast, the non-proficient labelers performed significantly above chance in the neutral condition (M = .67, SD = .23, t (12) = 4.86, p < .001, two-tailed, Cohen’s d = 1.45.), but not in the crossmapping condition (M = .32, SD = .25, t (12) =−.14, n.s., Cohen’s d = .04). In contrast,

Discussion

The present study reveals significant parallels between the development of numerical equivalence judgments and the development of non-numerical categories. These parallels suggest that, rather than developing along an idiosyncratic course, number concepts are built via the same mechanisms as other concepts. These include input and experiences that invite comparisons and direct attention toward particular dimensions.

First, there was a clear effect of crossmapping. Specifically, children’s performance on the matching task decreased dramatically when object similarity was pitted against numerical similarity. The youngest children tested, 3-1/2-year-olds, were quite affected by this manipulation and performed at chance. In contrast, these children recognized numerical equivalence in a neutral task where object similarity was the same for both the number match and the distractors, and therefore, was neither helpful nor interfering. Although 4-year-olds performed above chance in the crossmapping condition, their scores were significantly lower for crossmapped trials than they were for neutral trials. This discrepancy persisted until 5 years of age—at least two years from the time children begin recognizing numerical equivalence in this task.

This pattern suggests that number concepts are built through experience with high similarity comparisons. As in the color example discussed previously, when children encounter two sets, there is no reason for them to compare them in terms of number unless they already have number concepts. However, if the sets share many other commonalities, children may be drawn into a comparison process for other reasons. Perhaps the items are the same color, shape, or texture. The two sets also might be configured in similar patterns or aligned with each other spatially. The more ways that two sets are similar, the more likely children will be to compare them. Indeed, that is the finding of the present and previous research. Eventually, an awareness of numerical equivalence could emerge from these comparisons, even if they involve simple identity matches, because as children analyze the commonalities between sets more deeply, they may discover that number is one of them.

The present study also demonstrated significant effects of label knowledge on numerical matching. Across conditions, children who understood the meanings of the count words for the target sets performed significantly better than those who did not. Furthermore, only those children who understood the count word labels performed above chance in the crossmapping and sparse object-sparse set comparisons. Thus, whereas children’s numerical comparisons were influenced by variations in surface similarity, these influences could be mediated by children’s knowledge of the labels for the target sets.

Shared labels could promote children’s numerical comparisons just as they do for other dimensions—either by inviting a comparison like any other shared feature, or by directing attention to number. For example, when a set of cookies is labeled “three” and a set of dolls is labeled “three,” this could signal to children that these sets have something in common and invite further analysis of what the common feature could be. Of course, this mechanism could be engaged whether or not children can generate the number words themselves (e.g., a parent could label the sets for them). However, if children understand the labels well enough to label sets on their own, it is much more likely to happen, and to happen with greater frequency.

Although the present results are consistent with the idea that number concepts are constructed though such processes, further experiments that use training would provide more direct evidence. One idea would be to provide labels within the comparison task, as in Rattermann and Gentner’s (1998) “Mommy, Daddy, Baby” experiment. In a number version, all of the sets on each trial could be given number names. If shared labels promote numerical comparisons, then such input should improve matching performance even for children, even if children do not already understand the labels. Another approach would be to give children practice labeling individual sets and then test whether such training facilitates comparisons when the labels are not provided. Training could also focus on experience with high similarity comparisons. Would children who have had experience with numerical identity matches go on to recognize more abstract numerical comparisons than children who had not? Although the present results cannot answer such questions, they suggest that such training would have a positive effect.

In conclusion, this study provides further evidence that the development of numerical comparisons resembles the development of other comparisons. This parallel suggests that number concepts are built gradually using the same domain general mechanisms as other concepts—mechanisms that are triggered by surface similarity and shared labels.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brown AL, Kane MJ. Preschool children can learn to transfer: Learning to learn and learning from example. Cognitive Psychology. 1988;20:493–523. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(88)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner JS, Olver RR, Greenfield PM, et al. Studies in cognitive growth. New York: Wiley; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS. The development of representation in young children. In: Reese HW, editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 22. New York: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman R. Epigenetic foundations of knowledge structures: Initial and transcendent constructions. In: Carey S, Gelman R, editors. Epigenesis of mind: Essays on biology and cognition. Hillsdale, N. J: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 293–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman R. A rational-constructivist account of early learning about numbers and objects. The psychology of learning and motivation. 1993;30:61–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D. Metaphor as structure mapping: The relational shift. Child Development. 1988;59:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D, Rattermann MJ. Language and the career of similarity. In: Gelman SA, Byrnes JP, editors. Perspectives on language and thought: Interrelations in development. London: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 225–277. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D, Toupin C. Systematicity and surface similarity in the development of analogy. Cognitive Science. 1986;10:277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Holyoak KJ, Junn EN, Billman DO. Development of analogical problem-solving skill. Child Development. 1984;55:2042–2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Jordan N, Levine SC. A mental model for early arithmetic. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1994;123:284–296. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.123.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M, Gentner D, Uchida N. Children’s theories about word meaning: The role of shape similarity in early acquisition. Cognitive Development. 1994;9:45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Klibanoff RS, Waxman SR. Preschoolers’ acquisition of novel adjectives and the role of basic level kind. In: Greenhill A, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Boston University Confernce on Language Development; Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press; 1998. pp. 442–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kotovsky L, Gentner D. Comparison and categorization in the development of relational similarity. Child Development. 1996;67:2797–2822. [Google Scholar]

- Markman EM. Categorization and naming in children: Problems of induction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Marzolf DP, DeLoache JS. Transfer in young children’s understanding of spatial representations. Child Development. 1994;65:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mix KS. Preschoolers’ recognition of numerical equivalence: Sequential sets. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1999a;74:309–322. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1999.2533. Special Issue on the Development of Mathematical Cognition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mix KS. Similarity and numerical equivalence: Appearances count. Cognitive Development. 1999b;14:269–297. [Google Scholar]

- Mix KS. The construction of number concepts. Cognitive Development. 2002;17:1345–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Mix KS, Huttenlocher J, Levine SC. Do preschool children recognize auditory-visual numerical correspondences? Child Development. 1996;67:1592–1608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mix KS, Huttenlocher J, Levine SC. Multiple cues for quantification in infancy: Is number one of them? Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:278–294. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattermann MJ, Gentner D. The effect of language on similarity: The use of relational labels improves young children’s performance in a mapping task. In: Holyoak K, Gentner D, Kokinov B, editors. Advances in analogy research: Integration of theory and data from cognitive, computational, and neural sciences. Sofia: New Bulgarian University; 1998. pp. 274–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rattermann MJ, Gentner D, DeLoache J. Young children’s use of relational similarity in a transfer task. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Baltimore, MD. 1987. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Rattermann MJ, Gentner D, DeLoache J. Effects of competing surface similarity on children’s performance in an analogical task. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Kansas City, MO. 1989. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Sandhofer CM, Smith LB. Learning color words involves learning a system of mappings. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:668–679. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel LS. The role of spatial arrangement and heterogeneity in the development of concepts of numerical equivalence. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1973;27:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB. Young children’s understanding of attributes and dimensions: A comparison of conceptual and linguistic measures. Child Development. 1984;55:363–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB. From global similarities to kinds of similarities: The construction of dimensions in development. In: Voisniadou S, Ortony A, editors. Similarity and Analogical Reasoning. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB. The concept of same. In: Reese HW, editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 24. New York: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 215–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SR, Hall DG. The development of a linkage between count nouns and object categories: Evidence from fifteen- to twenty-one-month-old infants. Child Development. 1993;64:1224–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SR, Markow DB. Words as invitations to form categories: Evidence from 12- to 13-month-old infants. Cognitive Psychology. 1995;29:257–302. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn K. Children’s understanding of counting. Cognition. 1990;36:155–193. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(90)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn K. Origins of numerical knowledge. Mathematical Cognition. 1995;1(1):35–60. [Google Scholar]