Abstract

Although prior research has identified increases in cigarette smoking following trauma exposure, no studies have examined longitudinal trajectories of smoking following rape. The present investigation identifies and characterizes longitudinal (< 3 months, 3-6 months, and > 6 months post-assault) trajectories of smoking (N = 152) following a rape in a sample of 268 sexual assault victims participating in a forensic medical exam. Further, we examine acute predictors of subsequent smoking trajectories. Of participants endorsing smoking post-rape, a two-class solution was identified, with the majority of participants (74.6%) evidencing moderate smoking with a slight decrease over time and remaining participants showing heavy smoking with a slight increase over time. Having sustained an injury, minority status, and post-exam distress all predicted subsequent smoking trajectory.

Keywords: Sexual Assault, Rape, Smoking, Cigarettes

An estimated 50-70% of individuals in the U.S. experience at least one potentially traumatic event (PTE) during their lifetime (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; Kilpatrick et al., 2003). For women, one of the most prevalent PTEs is sexual assault. Over 15 million women (12.6%) in the U.S. are victims of completed rape (Kilpatrick, Edmunds, & Seymour, 1992). In addition to mental health outcomes following traumatic exposure, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, risky health behaviors such as smoking also increase following exposure (Vlahov, Galea, Ahern, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2004). Importantly, tobacco use is the most prominent and preventable cause of mortality in the U.S. (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004; McGinnis et al., 1993), and therefore is an important public health concern. Although it has been demonstrated that smoking increases post-trauma, little is known about the long-term patterns of behavior, and even less is known about predictors of trajectory. The present study examined longitudinal trajectories of smoking behavior following sexual assault. Given the potential health benefits of early intervention with affected individuals, we examined early predictors of post-assault smoking trajectories. Identification of such predictors may inform understanding of factors that influence post-trauma smoking behaviors and elucidate factors that may facilitate early identification of individuals at risk for sustained increases in smoking.

Studies have found a positive relationship between PTE exposure (occurring in childhood or adulthood) and smoking. Two large studies found that experiencing a PTE or adverse life experience in childhood was associated with increased risk of smoking in adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998; Walker et al., 1999). Similar to studies examining childhood exposure to PTEs, sexual assault in adulthood is associated with smoking (Cloutier, Martin, & Poole, 2002). However, these studies were retrospective in nature and are thereby limited by potential recall bias.

Recently, longitudinal studies have circumvented this potential recall bias. Vlahov and colleagues (Vlahov et al., 2004; Vlahov et al., 2002) examined cigarette use in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks. Nearly one in ten respondents reported increased consumption of cigarettes compared to pre-attack use frequency. Among those who smoked prior to the attack, 41.2% reported an increase in frequency of smoking in the subsequent 5-8 weeks following the attacks (Vlahov et al., 2002). Similarly, survivors of the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster reported increased substance use, relative to pre-disaster use, at 6- and 30-month follow-up assessments (Joseph, Yule, Williams, & Hodgkinson, 1993). Parslow and Jorm (2006) also implemented a longitudinal design and found that degree of exposure to a natural disaster was related to increased smoking among young adults.

As observed by Vlahov et al. (2002; 2004), psychological symptoms including PTSD and depression were risk factors associated with reported increases in smoking following exposure to the September 11th terrorist attacks. Similar findings regarding increased prevalence of current smoking (Acierno et al., 1996) and increased prevalence of nicotine dependence (Hapke et al., 2005) in association with exposure to traumatic events, including assault, and PTSD diagnosis have been reported within general population samples. It has been theorized that nicotine may be used to cope with negative affect (Pomerleau & Pomerleau, 1984), as its pharmacokinetic effects afford initial arousal (which may be reinforcing for depressive symptoms) and then tension reduction (which may be reinforcing for anxious symptoms). Following, it is important to examine distress and affective disorders in relation to smoking, as extant research suggests an association.

Although a positive relationship between traumatic event exposure and cigarette consumption has been demonstrated across age groups (Acierno et al., 2000; Cunningham, Stiffman, Dore, & Earls, 1994; Felitti et al., 1998; Hernandez, 1992), across traumatic event exposure types (Joseph, Yule, Williams, & Hodgkinson, 1993; Schnurr & Jankowski, 1999; Walker et al., 1999), and in association with psychopathology (Bremner, Southwick, Johnson, Yehuda, & Charney, 1993; Breslau, Davis, Andreski, & Peterson, 1991) no prior longitudinal studies have been conducted with a sample of recent rape victims. This is an important group to study, as rape is among the types of traumatic events most likely to lead to mental health difficulties, such as PTSD (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995).

Published studies have largely adopted analytic strategies that permit assessment of mean-level changes in behavior. However, it is more likely that trajectories of smoking behavior may differ substantially across participants, particularly given findings that subsets of participants (i.e., individuals with PTSD or depression) are at particular risk for increased smoking post-trauma. For example, imagine a case in which the data are best captured by three smoking trajectories: (1) a large subgroup with no change in post-trauma smoking behavior, (2) a small subgroup showing increased levels of smoking that persist over time, and (3) a large subgroup with initial high levels of smoking behavior that decrease over time. In this case, traditional analytic strategies that model mean-level change across the entire sample would likely support decreased smoking over time, missing an opportunity to characterize participants with significant health risk who show persistent high smoking with no decrease over time. Latent growth modeling approaches such as growth mixture modeling permit identification of these homogeneous subpopulations within the larger heterogeneous population (Muthen & Asparouhov, 2008).

The present examination attempted to address these limitations by (1) identifying and (2) characterizing post-rape trajectories of smoking behavior. Further, we examined early predictors that could serve to identify women who are likely to evidence sustained increases in smoking and, thus, who may benefit from smoking interventions. We were particularly interested in predictors that could be easily assessed in the context of a forensic exam. Based on prior research, we expected that women who reported having experienced a prior assault, who reported acute distress before and after the forensic exam, and who endorsed elevated anxiety at the time of the exam would be more likely to evidence sustained increases in smoking than women who had no prior assault history, were less distressed, or endorsed less anxiety at the time of the forensic examination.

Method

Participants

Female victims of recent sexual assault (i.e., forced vaginal, oral, or anal penetration, attempted or suspected rape that occurred within the prior 72 hours) ages 15 or older who reported the event to police and who participated in a post-sexual assault forensic medical exam and who completed at least one follow-up assessment were included in this report. Eligibility requirements at the medical exam included judgment on the part of project and medical staff that the woman or girl was able to participate in informed consent procedures. Parental consent and participant consent was required for adolescent participants.

Of 592 eligible victims, 442 (74.7%) agreed to participate. The present data are part of a larger intervention study described elsewhere (Resnick, Acierno, Amstadter, Self-Brown, & Kilpatrick, 2007). Participants were randomly assigned to a video intervention condition1 or treatment as usual. Of those assigned to a video intervention, 247 (87%) watched more than half of the content which was the criterion for having received treatment. That number, combined with those assigned to treatment as usual resulted in a group of 406 participants. Of this group of 406 participants at the time of the medical exam, 268 (66%) completed at least one follow-up assessment, and therefore are the focus of the present study. There were no differences among follow-up completers and noncompleters in terms of treatment condition, race, age or marital status, or measures of distress assessed at the time of the medical exam.

Three follow-up assessments were conducted. Time 1 occurred within 3 months post-sexual assault (M = 49 days, SD = 11), Time 2 occurred between 3 and 6 months post-sexual assault (M = 105 days, SD = 19), and Time 3 occurred at 6 months or more post-sexual assault (M = 196 days, SD = 79). Time 1 included 216 participants, Time 2 included 134 participants, and Time 3 included 219 participants. The average age of participants was 26 years old (SD=10); further demographic characteristics of participants are displayed in Table 1. For the analyses in this paper, participants who reported that they were Hispanic, Black, Asian, or Native American were classified as minority race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Demographic and Historical Variables of Sample (n=268)

| Variable | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 58.7 | 157 |

| Black | 37.7 | 101 |

| Asian | 1.5 | 4 |

| Hispanic | 1.5 | 4 |

| Native American | 1.1 | 3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 81.6 | 213 |

| Divorced or separated | 8.4 | 22 |

| Widowed | 1.9 | 5 |

| Married/cohabitating | 8.0 | 21 |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 28.2 | 74 |

| Employed or student | 71.8 | 188 |

| Prior history of assault | ||

| Yes | 40.7 | 109 |

| No | 59.3 | 159 |

Measures

A structured clinical interview entitled the Sexual Assault Interview was developed for this study. The assault history/characteristics sections were developed following the National Women's Study Traumatic Events Module and evaluated in prior epidemiological studies (Kilpatrick et al., 1997; 2000). The interview collected data regarding victimization, fear of death or injury during assault, injury during assault, and relationship to the assailant, and was administered at first follow-up assessment. Sexual assault history was assessed using behaviorally specific terms to ask women about experiences in which a man or boy made them have sex by using force or threat of harm to them or someone close to them. It was clarified that by sex we meant “putting a penis or fingers or other objects in your vagina, mouth, or anus”.

Lifetime sexual or physical assault included incidents of vaginal, anal, or digital penetration that included force or threat of force or physical attacks by someone who intended to seriously injure or kill the participant.

Minority status was defined as being non-White versus White. Age was assessed via self-report. Marital status was defined as being single, divorced/separated, widowed, or married/cohabitating. This variable was used dichotomously (married/cohabitating versus all other categories). Employment status was defined as being unemployed or employed/student.

Prior to, and following, the rape exam, women were asked to rate their current distress on a 0- to 100-point scale “where zero represents total calm and relaxation and 100 represents extreme emotional distress” on the Subjective Units of Distress (SUDs) scale (Wolpe, 1958), which widely used in anxiety research. Psychometric validation is offered by Kaplan, Smith, and Coons (1995) who found the measure highly correlated with more complex self-report indices requiring far more effort to complete, including the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (r = .69) and the Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist (r = .53).

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990) was administered at the forensic medical evaluation. This questionnaire is a 21-item self-rating scale of anxiety symptoms. At the post-exam assessment participants were asked to rate the degree to which they were bothered by each symptom, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely), “right now.” Prior research has demonstrated the instrument's internal consistency and convergent validity with the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Steer, Ranieri, Beck, & Clark, 1993). Coefficient alpha for the current study sample was .95.

At each follow-up assessment participants completed a measure of smoking. Participants were categorized as having a lifetime history of smoking if they endorsed smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Participants were classified as current smokers if they answered yes to, “Do you smoke cigarettes now?” They were queried regarding the number of days within the previous month they smoked “On how many of the past 30 days did you smoke cigarettes?”, and the number of cigarettes smoked per smoking day “On the average, when you smoked during the past 30 days, about how many cigarettes did you smoke a day?” Responses to these two questions were multiplied to determine the number of cigarettes smoked in a month. Finally, participants were asked, “Since the assault, have you increased the number of cigarettes you smoke daily?” and “Since the assault, have you increase the number of days on which you smoke cigarettes? A yes to either question was used to determine reported increase in smoking compared to pre-assault smoking frequency or amount.

Procedures

A project coordinator supervised a small team of on-call responders who were available to go to the hospital 24 hours per day to administer informed consent and study procedures. Next, women and girls in either condition were asked to participate in a study evaluating different types of information at the time of the medical exam and how such information might be associated with later functioning. Those in the non-video condition were told that they would be given a brief questionnaire and would be asked to rate their anxiety level at two points during the visit. Those in a video condition were told that they would be shown a brief video about the physical exam they would be receiving. In addition they were told that they would complete a brief questionnaire and rate their anxiety level at two points during the visit.

Immediately prior to the forensic medical exam, and for participants in a video condition, immediately prior to presentation of the video, participants were asked to provide a SUDs rating. Those in a video condition then watched the videotape, followed by the forensic exam, while those in the standard treatment condition proceeded directly to the forensic exam. Immediately post-exam participants completed a brief assessment that included the BAI (see Resnick, Acierno, Kilpatrick, & Holmes, 2005). Participants were contacted within the next several days and scheduled for the Time 1 (targeted at 6 weeks post-rape) follow-up interviews. Interviews were highly structured and were conducted by a bachelor's level coordinator with several years of experience. The interviewer also administered self-report measures and was blind to treatment condition throughout the course of the study. Women and adolescents were again asked to give informed consent to participate in follow-up assessments.

Data Analysis

We employed a three-step data analytic plan. First, descriptive analyses were conducted. Second, growth mixture modeling was conducted to identify trajectories of post-rape smoking behavior participants reporting any smoking at any time since the rape (N = 152). Third, a multinomial logistic regression, using nonsmokers as the base, was conducted to determine whether variables would predict class membership (N = 268).

Identification of distinct classes of smoking trajectories was completed using growth mixture modeling with latent variables conducted using Mplus Version 4.21 (Muthen & Muthen, 2004). Growth mixture modeling combines a person-oriented approach with conventional variable-oriented growth curve modeling, permitting continuous latent growth factors (intercept and slope) to be related to time (Muthen, 2004). Whereas conventional growth modeling assumes a single population and estimates a mean growth curve, growth mixture modeling uses categorical latent variables (e.g., trajectory classes) to capture variation in homogenous classes of development over time. Conventional growth modeling strategies also assume that covariates affect growth factors in the same manner across all individuals. In contrast, growth mixture modeling relaxes this assumption and permits differences in growth parameters across latent trajectory classes. Growth mixture modelings are estimated with maximum likelihood with robust standard errors, which permits analysis of data missing at random (MAR). The minimum covariance coverage recommended for a reliable model is .10 (Muthen & Muthen, 2004). Missing data coverage in the present study fell within acceptable levels, ranging from .30 to .80. Accordingly, MPlus missingness option was applied to all analyses. Thus, multiple imputation is used to generate multiple data sets with parameter estimates averaged across analyses and standard errors are calculated using the observed means across analyses as well as the observed between-analysis variation in parameter estimates (for more information on missingness treatment and applications in MPlus, see Morgan-Lopez. & Fals-Steward, 2007).

Evidence for different trajectory classes exists when models with 2 or more latent classes provide a better fit to the data. Classification of respondents is based on estimated posterior probabilities that indicate the likelihood of a particular case belonging to each trajectory class. Model fit is indicated by the log-likelihood value, with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) recommended to compare non-nested models with different numbers of latent classes for the best fit to the data (Muthen, 2004). A lower BIC value signifies a better-fitting model. Other considerations in selecting the preferred model include distinguishable latent classes based on classification quality with posterior probabilities, divergence of class trajectories, and adequate class sizes (Muthén, 2004). Recent simulations using available fit indices and tests suggest that the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test may be a preferred indicator of classes across all models considered (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthen, 2007). Analyses were limited to linear models as estimation difficulties were encountered in attempts to add quadratic and square root terms. Final participant latent growth trajectories were modeled with class, intercept, and slope regressed on the treatment condition covariate. Class assignment was calculated using posterior probabilities.

Results

Descriptives

Over half of the sample (50.9%) reported a lifetime history of smoking (excluding those who reported new onset of smoking post-rape). At Time 1 there were 120 current smokers (53.6% of total sample) reporting an average of 23.4 (SD = 8.7) smoking days per month. There were 61 current smokers (46.9%) at Time 2 reporting an average number of 24.5 (SD = 8.5) smoking days per month. At Time 3, there were 109 current smokers (50.9%) reporting an average number of 23.1 (SD = 10.3) smoking days per month. Per smoking day, current smokers reported using an average of 11.2 (SD = 8.6) cigarettes per day at Time 1, 12.1 (SD = 9.3) cigarettes per day at Time 2, and 11.7 (SD = 8.5) cigarettes per day at Time 3. Among current smokers at Time 1, 59.7% reported increasing either the number of days that they smoked or the number of cigarettes smoked per day, at Time 2, 64.1% reported any increase, and at Time 3, 48.2% reported any increase compared to pre-rape frequency and/or amount. Collapsed across follow-up time points, an average of 57.3% of current smokers reported an increase in smoking post-rape. There were 11 new onset cases of smoking (i.e., women who reported starting smoking post-rape), which is 15.5% of the sample who previously reported no history of smoking. Associations among predictors of interest are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Associations among predictor variables (N = 268)

| Minority | Married | Injury | Stranger | Prior assault |

Life threat | Age | Pre-exam SUDS |

Post-exam SUDS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | .03 | ||||||||

| Injury | −.14* | .04 | |||||||

| Stranger | −.07 | .02 | .07 | ||||||

| Prior assault |

−.08 | .04 | .19** | −.13* | |||||

| Life threat | .34*** | .06 | .16** | .18** | −.01 | ||||

| Age | .11 | .46*** | .26*** | −.01 | .19*** | .22*** | |||

| Pre-exam SUDS |

.02 | .06 | .11 | −.19** | −.02 | .03 | .11 | ||

| Post-exam SUDS |

.06 | .09 | .08 | −.11 | −.06 | .15* | .08 | .59** | |

| BAI total | −.04 | .06 | .04 | −.17** | .43*** | .32*** | .04 | .43** | .32** |

Notes. Statistics reported between dichotomous variables are Phi coefficients, which are interpreted similarly to Pearson's r. Pearson's r is provided above for all continuous variables, with point-biserial correlations provided for associations between dichotomous and continuous data. Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS). Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Trajectories of Smoking

A traditional growth curve analysis on the entire sample of smokers (one-class model) was initially conducted, providing a point of comparison for increases in numbers of classes (Table 3). Next, two- and three-class models were assessed. As shown in Table 4, the two-class model was judged to show the best fit to the data, as demonstrated by decrease in BIC values, the high entropy value, and the significant Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test. Although the three-class solution showed further decrease in BIC and improved entropy, the bootstrap likelihood ratio test was not significant and the smallest group n of 3 (2% of the participants who endorse smoking at any time point) falls just above the recommendation for no less than 1% of total count in one class. Accordingly, the two-class solution was selected.

Table 3.

Fit Statistics for Growth Mixture Models (n = 152)

| Model | Number of Groups (k) |

BIC | Entropy | Smallest group n | BLRT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 1 | 4537.68 | NA | 152 | ** |

| 2 | 4522.99 | .84 | 40 | LL = −2241.32, p <.001 | |

| 3 | 4509.11 | .89 | 3 | LL = 2223.81, p = 1.00 |

Notes. Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC); Bootstrap Parametric Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT); Entropy and BLRT values are not available for single group models (NA).

Table 4.

Parameters for Two-Class Growth Mixture Model (n = 152)

| Intercept |

Slope |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | n | Parameter | SE | Parameter | SE |

| Moderate Smokers | 112 | 213.12 | 34.65 | −37.06 | 15.61 |

| Heavy Smokers | 40 | 503.51 | 61.56 | 74.43 | 29.51 |

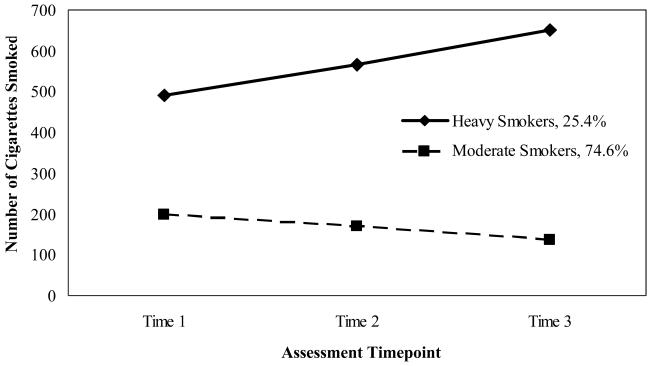

The two-class solution is shown in Figure 1, with parameters for each class provided in Table 3. The majority of participants (74.6%) were in Class 1, characterized by moderate numbers of cigarettes consumed at 3 months with a slight decrease in cigarettes consumed over the course of the subsequent 6 months. Class 2 participants evidenced high numbers of cigarettes smoked at the first timepoint with a slight increase in smoking over the course of the next 6 months. Probability for correct classification was .98 for Class 1 and .90 for Class 2, further supporting the two-class model. For descriptive purposes, these classes are labeled Moderate Smokers (Class 1) and Heavy Smokers (Class 2). As expected, assignment to treatment group did not significantly influence class membership (Logistic Odds Ratio = 1.88, CI = 0.62-5.71). Non-smokers were considered Class 0.

Figure 1.

Latent Class Trajectories of 2-Class Model of Post-Trauma Smoking Behavior

Acute Predictors of Smoking Trajectory

A multinomial logistic regression, with the non-smoking group indicated as the base, was conducted to examine the degree to which factors measured during the forensic exam predicted class membership (see Table 5). The model was found to fit the data adequately across indices of goodness-of-fit (see Table 5 for Model Fit Information); Pearson χ2 (458) = 505.63, p = .08; deviance χ2 (458) = 428.62, p= .83. Pseudo R2-square analyses further supported the utility of the overall model, Cox and Snell R2 = .20; Nagelkerke R2 = .23; McFadden R2 = .11. As shown in Table 5, minority status, injury, and post-exam distress were all found to significantly contribute to the overall model of group membership. More specifically, parameter estimates suggested that having sustained an injury increased the likelihood that individuals would later evidence heavy smoking trajectories relative to moderate smoking trajectories, B = .83, SE B = .36, Wald (1) = 5.34, p < .05, Exp (B) = 2.29, CI = 1.13 – 4.64. Minority status (non-Caucasian) was associated with decreased likelihood of membership in the heavy smoking group, relative to the non-smokers, B = −1.63, SE B = .57, Wald (1) = 8.25, p < .01, Exp (B) = .20, CI = .06-.60. Increased SUDS post-exam was also associated with decreased likelihood of being in the heavy smoking group relative to the non-smoking group, B = −.03, SE B = .01, Wald (1) = 7.70, p < .01, Exp (B) = .97, CI = .95 – .99.

Table 5.

Acute predictors of class membership

| −2 Log Likelihood of Reduced Model |

Comparisons χ2 (2, N = 268) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 429.51 | .89 |

| Minority (non Caucasian) | 438.53 | 9.91** |

| Employment | 431.16 | 2.54 |

| Incident characteristics | ||

| Injury | 437.81 | 9.19* |

| Life threat during rape | 428.75 | .13 |

| Raped by stranger | 434.12 | 5.49 |

| Acute psychological factors | ||

| Prior assault | 431.74 | 3.12 |

| Pre-exam SUDS | 432.14 | 3.52 |

| Post-exam SUDS | 439.67 | 11.04** |

| ER BAI Total | 432.29 | 3.67 |

Notes: The final model was significant, −2 log likelihood of reduced model =493.51, χ2 (18) = .23, p < .001. Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS). Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Prevalence of smoking in this sample, both lifetime and current, was strikingly high. Over half of the sample reported a history of smoking, a prevalence approximately four times higher than found in the general population for those with comparable demographics (Escobedo, Anda, Smith, Remington, & Mast, 1990). Further, over the course of the follow-up assessments 15.5% of previous non-smokers reported new onset of smoking. Participants were part of an examination of a video intervention developed to reduce post-rape substance use (Resnick, Acierno, Amstadter, Self-Brown, & Kilpatrick, 2007); as the video addressed post-rape smoking very briefly as a potential negative coping strategy, we did not expect differences in post-rape smoking behaviors to be related to participation in the video condition. Nonetheless, our findings that the video intervention did not influence subsequent smoking behaviors highlights the importance of implementing interventions targeted specifically at smoking behaviors (Fiore et al., 2000; Services, 2000). Since sexual assault victims who report the crime to police or other authorities receive routine post-rape medical care in cases of rape or suspected rape (Ledray & Kraft, 2001), the medical setting could provide the infrastructure in which secondary prevention services could be delivered (Acierno, Resnick, Flood, & Holmes, 2003; Resnick et al., 2007).

The present investigation represents the first study to prospectively characterize latent growth trajectories of smoking behavior following a rape. Consistent with prior research, traditional analytic strategies indicated that participants reported increased smoking following trauma exposure, with mean level smoking remaining relatively stable over time (Vlahov et al., 2004; Vlahov et al., 2002; Vlahov, Galea, Ahern, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2004). However, these mean level changes did not accurately capture participant trajectories of smoking behaviors, with subsets of participants found to show markedly different patterns of post-rape smoking behaviors. Growth mixture modeling suggested that cigarette consumption by participants endorsing any smoking post rape was best characterized by two trajectories. Most smokers (74.6%) evidenced moderate smoking at 3 months with a slight decrease in smoking over the subsequent 6 months. Heavy smokers consumed more than twice as many cigarettes as moderate smokers at 3-months post-rape, evidencing increased smoking over time. Heavy smokers, in particular, are at significant health risk and their trend toward continued increases in consumption is cause for concern. Clearly, early identification and efforts at harm reduction with this subset of rape victims is warranted.

Given the potential utility of early identification and intervention with victims of rape who may be at-risk for concerning levels of cigarette use, we were interested in the degree to which demographic, incident characteristics, and psychological information available to professionals during the forensic examination would predict subsequent class membership. Multinomial logistic regression analyses supported the utility of these early predictors in identifying subsequent class membership likelihood, with participant minority status, injury, and post-exam distress found to contribute to the model. Minority status was related to decreased likelihood of membership in the heavy smoking group, which is consistent with recent US statistics showing that the highest average number of cigarettes consumed per day is reported by Caucasians (Adams & Schoenborn, 2006).

Interestingly, having sustained an injury during the rape increased likelihood of being in the heavy smoking group. Although prior examinations have not examined the impact of injury on post-trauma smoking behavior, injury-related risk for higher-risk smoking is consistent with evidence that physical injury confers increased risk of developing PTSD (Koren, Hemel, & Klein, 2006). Of note, many of the post-injury neurobiological factors proposed to contribute to PTSD (Koren, Hemel, & Klein, 2006), also overlap with the neurobiology of nicotine (Fu et al., 2007). The association between injury and smoking may also be related to attempts at pain management, or due to restricted activity levels.

Unexpectedly, increased SUDS following participation in a forensic exam was associated with decreased likelihood of being in the heavy smoking trajectory relative to the non-smoking trajectory. Also, neither pre-exam SUDS or self-reported acute anxiety predicted subsequent smoking trajectory. Based on prior evidence that psychiatric history was associated with increased risk of smoking, we expected that acute indices of distress would predict increased likelihood of high-risk smoking behaviors. However, indicators of distress so close to the trauma may function very differently than prior psychiatric diagnosis, which may be more stable and/or less situational in nature, in predictive utility. This is important information for medical professionals, who may interpret decreased patient-reported distress as a positive sign for long-term adjustment.

There are several limitations to this study that warrant mention. Our data are based solely on self-report measures, and therefore are susceptible to response bias. It is unknown if completers versus non-completers differed in prior history of assault, which may affect smoking. Future studies should employ biological markers of smoking, and may also want to examine moderators of smoking behavior. Since we did not measure frequency or amount of smoking pre-assault, it is unknown the degree to which pre-assault smoking affected post-assault smoking. Similar to many longitudinal studies, attrition and a relatively small sample affected power. Rape victims reporting to the police or other authorities may differ from rape victims in the general population in terms of assault characteristics and prevalence of mental health and behavioral functioning variables. Data indicate that a minority of rape victims receive medical care (Resnick et al., 2000). Reporting the assault to police or other authorities which is associated with more stereotypic rape characteristics such as fear of death or injury, injury, and stranger assailant has been found to be a primary predictor of receipt of post-assault medical care. Future research with more representative samples of recent rape victims is needed to assess patterns of smoking over time following assault. Lastly, nicotine may be anxiolytic or anxiogenic and therefore future studies should assess the functional role of smoking in rape victims, motives for use, and the role of motivational stages of change (Hughes & Carpenter, 2004), as this information may greatly inform intervention attempts. Nonetheless, the present study contributes to the literature by providing longitudinal data on smoking behaviors in a sample of rape victims, a sample in which similar methodology previously had not been employed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by:

National Institute on Drug Abuse grant no. R01 DA11158 entitled “Prevention of Post Rape Psychopathology and Drug Abuse” (Heidi Resnick, PI);

Medical University of South Carolina Healthy South Carolina Grant-in-Aid Initiative entitled “Multidisciplinary Treatment of Acute and Long Term Health Effects of Rape Victimization: Development of A Model Program”;

NIH sponsored Medical University of South Carolina General Clinical Research Center Supported Study, 5M01 RR01070;

NIMH R01MH068626, entitled “New Longitudinal Methods for Trauma Research” (Daniel King, PI).

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Grant No. 1-UD1-SM56070, entitled “Service Systems Models Intervention Development and Evaluation Center” (Benjamin Saunders, PI).

Footnotes

Participants were randomly assigned to either standard care or one of 3 video conditions that included: 1) a full video (FV) which provided information about the medical exam and psychoeducation about post-rape reactions and coping strategies post-rape; 2) the medical exam component only (ME); or 3) the psychoeducation component only (PE). The latter 2 conditions were implemented as part of a study designed to dismantle specific video content and were instituted after 231/442 participants had been recruited as part of an initial study comparing FV to standard care. Because the sample sizes in the ME and PE only conditions were insufficient to examine separately we combined the groups assigned to a video condition into a single treatment group and compared this group with standard care for the purposes of this report. Specifically, of 268 participants with follow-up data, 107 were in the standard care condition, 94 were in the FV group; 31 were in the ME group, and 36 were in the PE group. More detailed information is provided in Resnick, Acierno, Amstadter et al., (2007).

References

- Acierno R, Kilpatrick D, Resnick H, Saunders BE, DeArellano M, Best CL. Assault, PTSD, family substance use, and depression as risk factors for cigarette use in youth: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:381–396. doi: 10.1023/A:1007772905696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Violence assault, posttraumatic stress disorder and depression: Risk factors for cigarette use among adult women. Behavior Modification. 1996;20:363–384. doi: 10.1177/01454455960204001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Resnick HS, Flood A, Holmes M. An acute post-rape intervention to prevent substance use and abuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1701–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P, Schoenborn C. Health behaviors of adults. United States, 2002-2004 National Center for Health Statustics. Vital Health Statistics. 2006;10:38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney DS. Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:235–239. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier S, Martin SL, Poole C. Sexual assault among North Carolina women: prevalence and health risk factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56:265–271. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.4.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham RM, Stiffman R, Dore P, Earls F. The association of physical and sexual abuse with HIV risk behaviors in adolescence and young adulthood: Implications for public health. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1994;18:233–245. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo LG, Anda RF, Smith PF, Remington PL, Mast EE. Sociodemographic characteristics of cigarette smoking initiation in the United States. Implications for smoking prevention policy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;12:1550–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline. US Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fu SS, McFall M, Saxon AJ, Beckham JC, Carmody TP, Baker DG, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and smoking: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:1071–1084. doi: 10.1080/14622200701488418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapke U, Schumann A, Rumpf H, Ulrich J, Konerding U, Meyer C. Association of smoking and nicotine dependence with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a general population sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193:843–846. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000188964.83476.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez JT. Substance abuse among sexually abused adolescents and their families. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;13:658–662. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90059-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. The feasibility of smoking reduction: An update. Addiction. 2004;100:1074–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Yule W, Williams R, Hodgkinson P. Increased substance use in survivors of the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1993;66:185–191. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D, Smith T, Coons J. A validity study of the Subjective Unit of Discomfort (SUD) score. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development. 1995;27:195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainment. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Edmunds CN, Seymour AK. Rape in America. National Victim Center; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationship between violent assault and substance abuse in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren D, Hemel D, Klein E. Injury increases the risk for PTSD: An examination of potential neurobiological mediators. CNS Spectrums. 2006;11:616–624. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900013675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledray LE, Kraft J. Evidentiary examination without a police report: Should it be done? Are delayed reporters and nonreporters unique? Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2001;27:396–400. doi: 10.1067/men.2001.117421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270:2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, editor. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Asparouhov T, editors. Growth mixture modeling: Analysis with non-Gaussian random effects. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus Version 3.11. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS. Neuroregulators and the reinforcement of smoking: Towards a biobehavioral explanation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1984;8:503–513. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Acierno R, Amstadter AB, Self-Brown S, Kilpatrick DG. An acute post-sexual assault intervention to prevent drug abuse: Updated findings. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2032–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Holmes M. Description of an early intervention to prevent substance abuse and psychopathology in recent rape victims. Behavior Modification. 2005;29:156–188. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Acierno R, Waldrop AE, King L, King D, Danielson C, et al. Randomized controlled evaluation of an early intervention to prevent post-rape psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2432–2447. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr P,P, Jankowski MK. Physical health and post-traumatic stress disorder: Review and synthesis. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 1999;4:295–304. doi: 10.153/SCNP00400295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Services U. D. o. H. a. H. Reducing tobacco use. A report of the US Surgeon General. Office of Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ranieri WF, Beck AT, Clark DA. Further evidence for the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1993;7:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Boscarino JA, Gold J, et al. Consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among New York City residents six months after the September 11 terrorist attacks. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:385–407. doi: 10.1081/ada-120037384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov, Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Boscarino JA, Bucuvales M, et al. Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, New York residents after the September 11th terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:988–996. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D. Sustained increased consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan residents after September 11, 2001. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(2):253–254. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, Koss MP, Von Korff M, Bernstein D. Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. American Journal of Medicine. 1999;107:332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe J. The process of reciprocal inhibition. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1958. [Google Scholar]