Abstract

Previous research with individuals undergoing surgery or diagnostic procedures provided a conceptual framework for analysis of radiation therapy, a common form of cancer treatment. The present investigation was designed to document the magnitude of anxiety patients experience in response to one particularly stressful form of radiation treatment. In addition, the change in anxiety responses with repeated exposures and individual differences among patients that may affect their adjustment were explored. In Part 1, gynecologic cancer patients receiving their first internal radiotherapy application were studied. As the time for treatment neared, subjective and physiologic indicants of anxiety and distress among the patients significantly increased. By 24 hours post-treatment, anxiety for all patients remained elevated. These post-treatment data are convergent with other investigations of post-treatment distress among cancer patients, but contrast with data obtained from those receiving treatment for benign conditions. A subset of the women who required two applications of radiotherapy participated in Part 2. These patients continued to respond negatively during the second treatment. Data on individual differences in anxiety responses (i.e., low vs. high anxiety) were obtained in both investigations and suggest that those with low levels of pre-treatment anxiety experience considerable disruption post-treatment.

Psychological cancer research has recently focused on the predictors of illness adjustment (e.g., Bloom, 1982), areas of life change following diagnosis and treatment (e.g., Andersen & Hacker, 1983), and anxiety in response to cancer surgery or chemotherapy (e.g., Gottesman & Lewis, 1982; Redd & Andrykowski, 1982). Despite radiation being a primary treatment modality (approximately 350,000 patients are treated annually), it has received little psychologic study. Clinical descriptions of patient reactions are available (Peck & Boland, 1977; Rotman, Rogow, DeLeon, & Heskel, 1977; Smith & McNamara, 1977; Welch, 1980; Yonke, 1967), and they have noted fears of the treatment (e.g., being burned or causing sickness, sterility, or even cancer) and vast individual differences among patients in their psychological reaction to the treatment have been recently found (Andersen & Tewfik, in press).

Previous research with individuals undergoing other forms of medical treatment, surgery, or stressful diagnostic procedures, provided a conceptual framework for analysis of radiotherapy. In this research different patterns of anxiety response data have been evidenced,1 but a decline in the magnitude of patients’ self-reported anxiety from pre- to post-treatment is most common (e.g., Cohen & Lazarus, 1973; Johnson, Dabbs, & Leventhal, 1970; Johnson, Leventhal & Dabbs, 1971; Johnson & Carpenter, 1980; Martinez-Urrutia, 1975). For example, Spielberger, Auerbach, Wadsworth, Dunn, and Taulbee (1973) assessed male surgical patients pre- and post-operatively with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970). Analyses revealed that state anxiety significantly declined at the post-operative assessment for patients that had reported either low or high pre-treatment anxiety. In contrast, trait anxiety remained relatively stable for all patients from pre- to post-surgery. Thus, the level of pre-operative state anxiety was linearly related to post-operative adjustment. Examination of anxiety among patients undergoing noxious diagnostic procedures has revealed findings similar to those obtained with surgical patients (e.g., Kaplan, Atkins, & Lenhard, 1982; Kendall, Williams, Pechacek, Graham, Shisslak, & Herzoff, 1979; Shipley, Butt, & Horwitz, 1979). For example, Margalit and his colleagues (Margalit, Teichman, & Levitt, 1980) administered the STAI to gynecology patients prior to and following hysterosalpingography. Patients’ trait anxiety scores remained stable while their state anxiety scores decreased after the procedure was completed. These data indicate that individuals receiving treatment for benign conditions respond with transient levels of situational anxiety and fear. These responses to the medical stressor are not so overwhelming, however, as to significantly alter patients’ reports of how anxious or fearful they generally feel, and thus no changes in dispositional anxiety were observed.

If predictions of patients’ anxiety responses to radiotherapy were made on the basis of this previous research, one might expect that patients’ anxiety responses to radiotherapy would be similar. Certainly with a measure of trait anxiety the responses from pre- to post-radiotherapy should remain stable. Even if cancer patients report significant distress due to radiotherapy, per se, they should be as able as others to distinguish how anxious they “generally” feel when reporting their anxiety levels. In terms of state anxiety, three factors might limit the generalization of the previous findings to the circumstances of a radiotherapy patient. First, data indicate that cancer inpatients as a group report greater anxiety over the circumstances of hospitalization than inpatients receiving treatment for nonmalignant conditions (Lucente & Fleck, 1972). Radiation therapy patients might therefore report substantial distress at all points of assessment. Second, post-operatively cancer patients report greater and more lasting state anxiety, general feelings of experiencing a crisis, and feelings of helplessness than are reported by general surgery patients (Gottesman & Lewis, 1982). Thus, a general decline in state anxiety for patients undergoing radiation might not be evidenced; instead distress may be maintained or possibly increased when a treatment is over. Third, radiation therapy also differs from many of the surgery and diagnostic procedures studied in that rather than a single episode, most patients undergo repeated radiotherapy treatments. Kendall et al.’s (1979) research with cardiac catherization patients and Shipley et al.’s (1979) research with endoscopy patients suggest, however, that even patients with nonmalignant diseases fail to adapt when undergoing repeated diagnostic procedures. Radiation therapy patients may also not adapt, and thus be as anxious when anticipating their second treatment as their first.

To examine the psychological responses to radiation therapy, a type of treatment was chosen that resembled a stressful surgical or noxious diagnostic procedure with the addition of radiation. Intracavity radiation (ICR) is a common component of treatment for gynecologic cancer (Newall, 1980; Perez, Knapp, & Young, 1982); approximately 50,000 cervical or endometrial cancer patients per year receive this treatment. Although no incisions are made, ICR possesses elements common to a surgical experience — for example, bowel preparation, induction of anesthesia, and sedative and pain medication during and after the treatment. For ICR, patients are transported to a surgical suite, general anesthesia is induced, and three 15-in. (38.10 cm) metal rod-like instruments are placed into the vagina. One rod is inserted into the uterus and the others are placed to the sides of the uterus opening. After patients are stabilized, the positioning of the instruments is radiographically ascertained and radioactive pellets are loaded into one of the rods. Patients are then transported to a hospital room for the 48- to 72-hour treatment period. During this time the positioning of the instruments must be maintained; consequently, patients must lie flat in bed and remain relatively motionless despite attendant discomforts. These noxious circumstances result in difficulties in eating and necessitate catheterization and the use of a bed pan. Radiation protection requires a private room and restricted visitation — family and friends are discouraged from visiting and the staff is limited to approximately 15 minutes of patient contact during each shift. Removal of the instruments and radioactive material usually occurs in the patient’s room and, although medicated, most women remain conscious. Many patients receive two ICR treatment periods, usually separated by 2 weeks.

One can easily surmise aspects of this treatment make it an extremely difficult experience. A few may be noted. The vaginal packing placed around the instruments to maintain their positions creates feelings of pelvic discomfort and pressure sensations, and removal of these materials has been described by patients as “excruciating. ” Simple tasks, eating and bed bathing, are very difficult if not impossible to perform. The time for removal of the radioactive source is individually determined, and when the time estimates previously told to the patient are extended, the hours become more difficult to bear. During these final hours, radiation induced fatigue is maximal, pelvic, back, and general body aches from lying relatively motionless are severe, and feelings of isolation and loneliness are extreme.

In Part 1 of the investigation, experiences of women receiving their first ICR treatment were examined. ICR patients were predicted to show considerable situational or state anxiety prior to their treatment. In addition, we hypothesized that as the actual time for treatment neared, anxiety would increase even further. However, we predicted that cancer patients, unlike healthy individuals, would not report a reduction in anxiety from pre- to post-treatment. While state anxiety was expected to fluctuate, we predicted that dispositional or trait anxiety would remain stable for these cancer patients from pre- to post-treatment, as it does for healthy individuals. In Part 2 of the investigation, anxiety responses of the women as they received two courses of ICR therapy were examined. Because patients receiving more than one exposure to a noxious medical procedure have frequently failed to demonstrate habituation to the stressor, we hypothesized that ICR patients would again respond negatively on a measure of state anxiety when anticipating their second ICR treatment. It was anticipated that trait anxiety scores would remain stable from pre- to post-treatment and from the first to the second ICR application.

In addition to assessing the change in anxiety with time and repeated exposures, a secondary focus was to determine if individual differences in patients’ response to the threat of ICR, as measured by patients’ pre-treatment level of state anxiety, might interact with outcome. Those voicing few anticipatory anxiety and fear responses might respond differently post-treatment or during repeated exposures than those high levels of anticipatory anxiety. In previous research, individuals with low levels of pre-treatment anxiety reported the lowest anxiety post-treatment and had the fewest complications, whereas patients with high levels of pre-treatment anxiety reported the highest anxiety and the most difficulties post-treatment (Kendall et al., 1979; see Mathews & Ridgeway, 1981, for a review).

Although situational anxiety was the area of primary interest, other measures provided supplementary information. Pulse rate was chosen as a physiological indicator of pre-treatment anxiety. While some (e.g., Fowles, 1982) have suggested that heart rate may reflect processes other than anxiety or emotional arousal, we hypothesized that if patients subjectively reported greater state anxiety as treatment neared, this would possibly be reflected in an objective indicator as well. Because poor adjustment to a difficult medical procedure may involve more than anxiety, the measurement of mood states and pain was used. Finally, although attending physicians and nurses had only limited contact with a patient during the ICR, we sought their evaluation as an overall indicant of the patient’s adjustment to the treatment. In previous research, medical staff raters had been inconsistent in their ability to distinguish patients that had exhibited more or less behavioral distress (Kendall et al., 1979; Vernon & Bigelow, 1974). However, we hypothesized that this may have been due to the raters’ limited familiarity with patients having short hospital stays for benign, non-life-threatening conditions. In contrast, a number of the ICR patients were well known to the medical raters who had cared for them during a lengthy diagnostic workup and recent inpatient admission(s). We felt these raters might therefore be more accurate in assessing a patient’s adjustment during this difficult treatment despite only brief observations during the actual ICR period.

PART 1

METHOD

Subjects

Women scheduled for intracavity radiation (ICR) treatments were eligible for participation if they were (a) between 20 and 80 years of age; (b) English speaking; (c) without signs of mental retardation, organic brain syndrome, or severe psychopathology; (d) not previously treated with internal radiotherapy; and (e) without other medical conditions preventing their participation. Eligibility determinations were made in collaboration with the Divisions of Gynecologic Oncology and Radiation Therapy at a large university hospital. Of those women scheduled for treatment during the 14-month study period, 4 declined, 6 were not approached due to scheduling difficulties, and 6 were ineligible for participation.

Nineteen women were studied. All were Caucasion and ranged in age from 23 to 78 years (M = 52.3, SD = 14.9). Average educational attainment was high school graduation plus some technical school or college. Most were not employed outside of their home, and the average family income was $10,000 to $20,000 per year. Disease extent ranged from Stage I to III, although the majority of the participants (84%) had Stage I or II disease of the cervix or endometrium.

ASSESSMENT MEASURES AND PROCEDURE

Subject Data

State Trait Anxiety Inventory

(STAI; Spielberger et al., 1970). This self-report inventory is designed to assess two dimensions of anxiety. The 20-item State scale asks subjects to indicate how they feel at the present time. This scale is thought to be a sensitive indicator of anxiety that is transitory and characterized by consciously perceived feelings of tension, apprehension, and heightened autonomic nervous system activity. The Trait scale consists of 20 items that ask subjects to describe how they generally feel and is thought to tap relatively stable individual differences in anxiety proneness. Scores on both scales may range from 20 to 80.

Profile of Mood States

(POMS; McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1971). This 65-item self-report inventory yields measures of six moods: Tension-Anxiety (T-A); Depression-Dejection (D-D); Anger-Hostility (A-H); Fatigue-Inertia (F-I); Confusion-Bewilderment (C-B); Vigor-Activity (V-A); and Total Mood Disturbance (TMD), a composite of the six scales. Subjects rate each mood item on a 5-point scale that ranges from not at all (0) to extremely (4). The following score ranges are possible: 0 to 36 for T-A; 0 to 60 for D-D; 0 to 48 for A-H; 0 to 28 for F-I; 0 to 28 for C-B; 0 to 32 for V-A; 0 to 200 for TMD. High scores reflect greater mood disturbance, excepting the V-A scale where a low score reflects mood disturbance.

Discomfort Rating Scale

A visual analog measure was used to assess patients’ physical discomfort during the ICR treatment. Patients were given a 10-cm line drawing with the phrases the most severe discomfort I can imagine and not at all uncomfortable as endpoint anchors, and asked to make a slash mark somewhere along the line corresonding to the magnitude of their current physical discomfort. A slash mark was subsequently assigned a score from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more discomfort.

Medical Staff Data

Physicians’ Rating Form

Based on Derogatis, Abeloff, and Melisaratos’ (1979) Patient Information, Attitude, and Expectancies form (PIAE), this measure asks the physician to make judgments regarding the following: the patient’s general attitude toward her illness, treatment, and recovery, and the medical staff; the amount and quality of information the patient possesses about her illness and the ICR treatment; and how realistic the patient’s expectancies are concerning her illness and the ICR treatment. Ratings were made by the gynecology physician with primary responsibility for a research participant’s care. A 7-point scale ranging from very negative/unrealistic (0) to highly positive/accurate (6) was utilized for each judgment, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 42.

Nurses’ Rating Form

Nursing records were kept of frequency of complaints of discomfort, requests for pain medications, and requests for information regarding the ICR treatment. The nursing staff also rated patients’ moods on the following POMS items chosen for their factor loadings and applicability to the ICR period: tense, hopeless, grouchy, active, fatigued, confused, nervous, unhappy, angry, alert, exhausted, and uncertain about things. The nurse responsible for the patient’s care made these ratings on her shift during the ICR treatment period and ratings were averaged across shifts; scores ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating judgments of more mood disturbance.

Chart Data

After the ICR treatment was completed, the following information was obtained: pretreatment pulse rates; names of the physicians who inserted and removed the radioactive sources; site and stage of disease; and ICR treatment length.

Procedure

Each subject was contacted for participation 2 to 7 days prior to her first ICR treatment and informed consent was obtained. Two days prior to the ICR treatment (pre-1) subjects were briefly interviewed and completed the STAI and the POMS inventories. At approximately 7 p.m. on the night before the ICR treatment (pre-2), subjects completed the State form of the STAI. During the ICR treatment, nurses completed their ratings of the patient’s moods, and patients rated their discomfort at 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. each day. On the day following the removal of the ICR (post), subjects completed the STAI and POMS inventories, the attending physician completed the physician’s rating form, and data were collected from the patient’s chart.

RESULTS

The factors of interest for the analyses were change in anxiety over time and the effect of level of pre-treatment state anxiety on women’s response to radiation therapy. To create two subgroups of women differing in pre-treatment anxiety, subjects’ pre-1 state anxiety scores were hierarchically ordered and the mean and median determined. Women with state anxiety scores of 41 or less (n = 8) were assigned to a low pre-treatment anxiety group, and the remaining subjects (n = 11) were assigned to a high pre-treatment anxiety group. Unequal cell size was due to three subjects having a score of 42. A general linear model that adjusts values according to unequal cell sizes and loss of subjects was used for the majority of the analyses. At post-testing; the low group had seven subjects and the high group had nine subjects; loss of subjects was due to early release from the hospital (n = 2); and surgery on the day after termination of the ICR (n = 1).

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) examining demographic and medical variables that may have confounded the comparison of the two anxiety groups was first conducted. Women differing in pre-1 state anxiety did not significantly differ (i.e., p>.10) on demographic or medical variables (i.e., education, employment status, income, religious affiliation, religiosity, age, number of previous hospitalizations, stage of disease, the physician who inserted and removed the radioactive material, length of treatment, and previous or concurrent cancer treatments). Results of the site of disease analysis approached significance (p<.06), suggesting that women with higher levels of pre-treatment state anxiety were more likely to have cancer of the cervix than of the endometrium.

Changes in state anxiety were examined with a 2 × 3 repeated measures ANOVA with the factors of Time (pre-1, pre-2, or post) and Pre-treatment Anxiety Level (low or high). A significant main effect for time was obtained, F(2,31) = 3.78,p<.04 (Ms: pre-1 = 43.4, pre-2 = 48.6, post = 46.6), as expected. Duncan multiple range tests revealed significant increases in state anxiety from the pre-1 to the pre-2 period. A significant decline in state anxiety was not found, however, at the post-treatment assessment. A main effect for pre-treatement anxiety level was also obtained, F (1,17) = 4.98, p< .04 (Ms: low = 42.6, high = 49.7), indicating that those individuals assigned to the high pre-treatment anxiety group reported greater state anxiety generally than those assigned to the low pre-treatment anxiety group. Finally, a significant Time × Pre-treatment Anxiety Level interaction was also obtained, F(2,31) = 5.02, p<.02. Multiple comparisons revealed that low and high pre-treatment anxiety level groups differed significantly in state anxiety at pre-1, but not at pre-2 and post. In addition, increases in state anxiety from pre-1 to pre-2, and from pre-1 to post were significant for the low pre-treatment anxiety level group only, with no significant change across the assessment periods in the level of state anxiety for the women reporting high pre-treatment anxiety (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mean State Anxiety Scores Pre- to Post-treatment for the First Intracavitary Radiation Treatment

| Level of Pretreatment Anxiety |

Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1 | Pre-2 | Post | |

| High | |||

| M | 50.0a | 52.5a | 46.7a |

| SD | 7.6 | 8.8 | 10.6 |

| Low | |||

| M | 36.8b | 44.6a,c | 46.6a,c |

| SD | 4.3 | 12.7 | 4.7 |

Note: Common superscripts across levels indicate no significant differences, while different superscripts indicate p <. 05.

A 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA on trait anxiety scores for the factors of Time (pre-1 or post) and Pre-treatment Anxiety Level (low or high) was conducted. As expected, neither the main effects for time or anxiety nor the Time × Pre-treatment Anxiety Level interaction were significant.

A 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA with Time (pre-1 or pre-2) and Pretreatment Anxiety Level (low or high) was conducted on the patients’ pretreatment pulse rates to examine autonomic evidence of anxiety and stress. Significant main effects for time, F(1,14) = 5.12, p<.05 (Ms: pre-1 = 80.9, pre-2 = 87.3), and pre-treatment anxiety level, F(1,16) = 5.87, p<.03 (Ms: high = 88.8, low = 79.4), were obtained. This indicated that the high pre-treatment anxiety group had higher pulse rates generally, and that both groups’ pulse rates significantly increased as the treatment approached.

A 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA with the factors of Time (pre-1 or post) and Pre-treatment Anxiety Level (low or high) was conducted for each POMS scale to determine if mood states other than anxiety were affected by this medical stressor. On the Vigor-Activity scale a significant main effect for time, F (1,14) = 4.68,p<.05 (Ms: pre-1 = 13.9, post = 9.4), was found, indicating that patients were significantly less active after the ICR treatment. A significant Time × Pre-treatment Anxiety Level interaction, F(1,14) = 4.95, p<.05 (Ms: low pre-1 = 14.5, low post = 7.0, high pre-1 = 13.3, high post = 11.8), was also obtained, indicating significant decreases in activity level after the first ICR treatment for the subjects low in pretreatment state anxiety. The Fatigue-Inertia analyses revealed a significant main effect for time, F(1,14) = 7.11, p<.02 (Ms: pre-1 = 6.8, post = 12.4), indicating that patients complained of more fatigue after the ICR treatment. Analyses for the remaining scales failed to yield significant differences.

Summary scores from patients’ discomfort, nurses’, and physician ratings were also evaluated, but none revealed significant findings.

PART 2

METHOD

Subjects

Thirteen of the 19 participants in Part 1 received a second course of the ICR therapy approximately 2 weeks after the first and were approached again for study participation. One woman in each of the anxiety groups declined, describing their first ICR treatment as so difficult that they did not wish to complicate their second treatment by participating in psychosocial research.

ASSESSMENT MEASURES AND PROCEDURE

Subject, medical staff, and medical chart measures, and the procedure and timing of data collection were identical to that used in Part 1.

RESULTS

In addition to the factor of interest, the effect of repeated exposures to a medical stressor, analyses also included the factors of change in anxiety over time and the effect of level of pre-treatment state anxiety. As with Part 1, two anxiety groups were created by hierarchically ordering the pre-1 state anxiety scores from the 11 subjects’ first ICR. Women with pre-1 state anxiety scores of 45 or less (n = 5) comprised the low pre-treatment anxiety group and the remaining subjects (n = 6) comprised the high pre-treatment anxiety group.2 A general linear model was utilized for the majority of the analyses, since after the second ICR the low group had four subjects and the high group had five subjects; loss of subjects were due to early discharges from the hospital.

One-way ANOVAs examining demographic and medical variables were conducted, and women differing in pre-treatment anxiety were not found to significantly differ (p> .10) on any variable. Women who received only one ICR treatment versus those who had received two also did not differ on these variables.

Changes in state anxiety for subjects receiving two ICR treatments were examined with a 2 × (3 × 2) ANOVA with Pre-treatment Anxiety Level (low or high) as the between-subjects factor, and Time (pre-1, pre-2, or post) and ICR (first or second) as within-subjects factors. Main effects for pretreatment anxiety level, time, and ICR, and the two-way interactions of these factors all failed to reach significance.

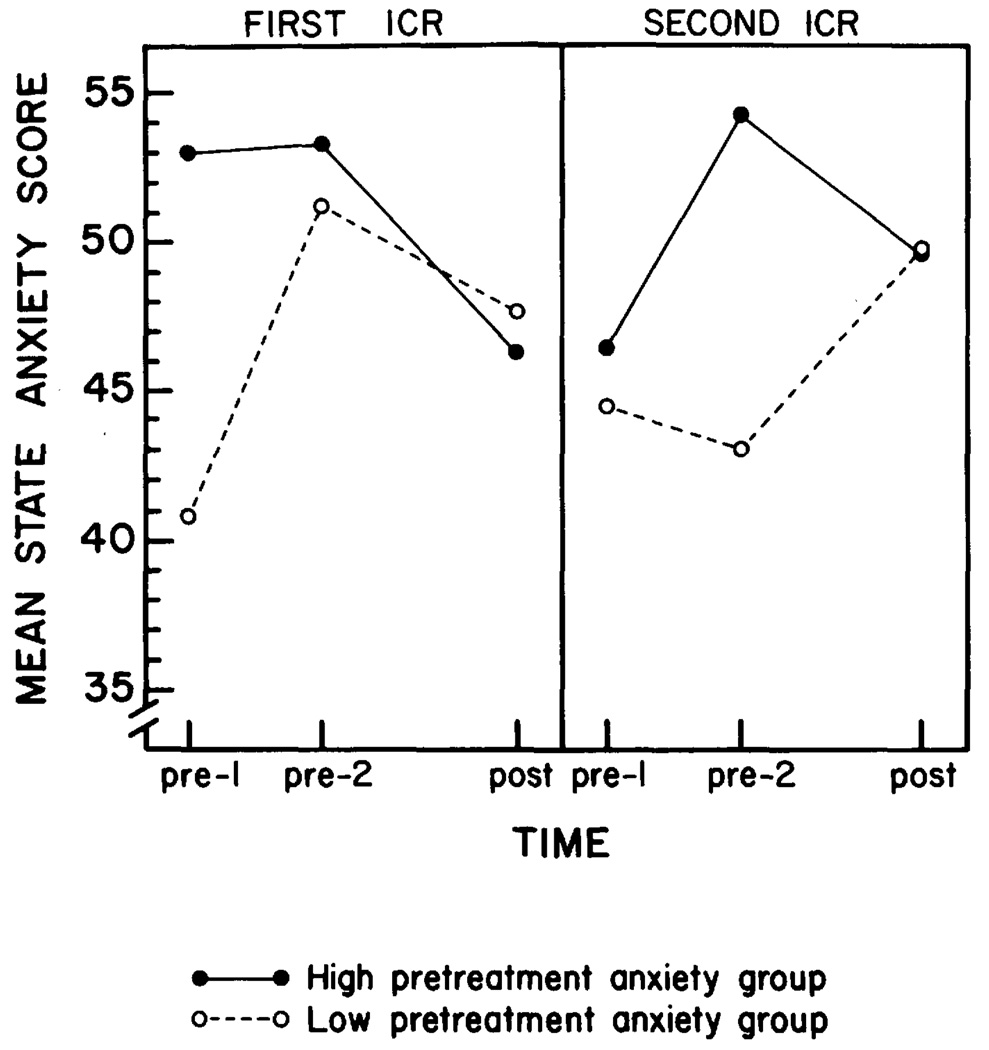

A Pre-treatment Anxiety Level × Time × ICR interaction was, however, significant, F(2,12) = 3.89, p<.05, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In conducting follow-up tests for this three-way interaction, we were interested in three main areas: overall differences between the first and second ICR; differences between low and high pre-treatment state anxiety patients for the first ICR; and differences between low and high pre-treatment state anxiety patients for the second ICR. (1) Duncan multiple range tests for the patients with low pre-treatment anxiety indicated that although the patients were significantly more anxious when they faced the second ICR than the first (pre-1), they reported comparable levels of state anxiety at post-treatment for each ICR. For patients with high pre-treatment anxiety, they were significantly more anxious when they faced the first rather than second ICR, although they were significantly more anxious when the second ICR concluded (post) than when the first ICR was concluded. (2) Duncan multiple range tests for the first ICR indicated that patients with low pre-treatment anxiety reported significant increases in state anxiety as treatment neared (pre-1 to pre-2) and even when treatment was concluded (pre-1 to post), although state anxiety had partially declined from the pre-2 extreme level. In contrast, the first ICR for patients with high pre-treatment anxiety had resulted in a non-significant increase as treatment neared (i.e., from pre-1 to pre-2) and a significant reduction in state anxiety from pre- to post-treatment. While the low and high pre-treatment anxiety groups significantly differed at the pre-1 assessment, they did not differ subsequently for the first ICR. (3) Duncan multiple range tests for the second ICR indicated that patients with low pretreatment anxiety reported little change in their state anxiety as treatment neared (pre-1 to pre-2), unlike the response for the first ICR. However, low pre-treatment anxiety patients reported a significant increase in state anxiety at the post-treatment assessment from the levels obtained pre-treatment. For patients with high pre-treatment anxiety, the same pattern of state anxiety responses were evidenced for the second ICR as for the first: State anxiety increased as treatment neared (i.e., from pre-1 to pre-2) and significantly decreased from pre-2 to post.

FIG. 1.

Data pattern for significant three-way interaction of Part 2. Left panel indicates the changes in state anxiety scores across time for high and low pre-treatment anxiety groups during the first ICR. Right panel indicates the changes in state anxiety for the same groups during the second ICR.

A 2 × (2 × 2) ANOVA on the trait anxiety scores from the 11 subjects who received two ICR treatments was conducted. Main effects for pre-treatment anxiety level (low or high), time (pre-1 or post), ICR (first or second), and the interactions of these factors were not significant, as expected.

A 2 × (2 × 2) ANOVA with Pre-treatment Anxiety Level (high or low), Time (pre-1 or pre-2), and ICR (first or second) as factors were conducted on the patients’ pre-treatment pulse rates. A main effect for ICR approached significance, F(1,8) = 4.37, p<. 07 (Ms: first ICR = 88.06, second ICR = 81.27), suggesting higher pulse rates generally for subjects when anticipating their first radiation treatment. Remaining factors and interactions were not significant.

A 2 × (2 × 2) ANOVA with Pre-treatment Anxiety Level (low or high), Time (pre-1 or post), and ICR (first or second) as factors was conducted on the POMS. On the Vigor-Activity subscale a significant main effect for time was obtained, F (1,7) = 12.07, p<. 01 (Ms: pre-1 = 13.9, post = 11.2),indicating that patients felt significantly less active after their ICR’s than before. A significant Time × ICR interaction was also obtained, F(1,7) = 27.4, p<.002 (Ms: pre-1 ICR 1 = 11.82, post ICR 1 = 11.89, pre-1 ICR 2 = 15.99, post ICR 2 = 10.63). Multiple comparisons revealed that patients’ activity levels were significantly higher prior to their second ICR than they were at any other time period. Main effects and interactions on the remaining POMS scales failed to yield significant differences.

Summary scores from patients’ ratings of discomfort, nurses’ ratings, and physician ratings were evaluted with a 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA for the factors of Pre-treatment Anxiety Level (low or high) and ICR (first or second). Patients’ ratings of discomfort yielded a main effect for pre-treatment anxiety level, F ( 1,9) = 5.8, p<.04 (Ms: low = 6.8, high = 3.4), indicating that individuals low in pre-treatment state anxiety judged their discomfort during the ICR periods to be greater than did women high in pretreatment state anxiety. In addition, a main effect for ICR was obtained for the Physician Rating Form, F(1,9) = 8.9, p<.02 (Ms: first = 25.3, second = 30.0). This indicated that physicians judged their patients as possessing significantly more information and more positive attitudes toward their illness and treatment after their final ICR than after their first.

DISCUSSION

Perhaps the most obvious clinical outcome from this investigation was the description of the stressful nature of this radiation treatment for gynecologic cancer patients. Prior clinical experience with patients had illustrated significant distress. Even during the course of the investigation one woman refused ICR treatments, and another women refused the second treatment and also temporarily discontinued her external radiation treatment. These clinical and objective data are convergent with previous reports of substantial anxiety among cancer patients generally (Derogatis, Morrow, Fetting, Penman, Piasetsky, Schmale, Henrichs, & Carnicke, 1983). In this investigation the magnitude of state anxiety at all assessments was expected to be considerable, and state anxiety scores ranged from the 74th to the 95th percentile for females (Spielberger et al., 1970). Despite the magnitude and duration of this anxiety, these cancer patient were as able as other individuals to distinguish “current” distress due to the ICR from their general levels of anxious feelings (i.e., state vs. trait anxiety).

Part 1 indicated that as the treatment time neared, from 2 days to the night before, patients became more agitated; they reported feeling more anxious and nervous and their pulse rates accelerated. Even after the first treatment was over, their anxiety did not dissipate and patients were fatigued and less active. The extreme post-treatment anxiety responses of these cancer patients contrast, however, with numerous reports from individuals undergoing surgery or diagnostic procedures who report state anxiety reductions post-treatment (e.g., Auerbach, 1973; Cohen & Lazarus, 1973; Martinez-Urrutia, 1975).

The data from women undergoing two ICR treaments in Part 2 provided preliminary information regarding habituation to noxious medical experiences. This issue is particularly important for cancer patients because treatment for many is a regimen or involves repeated diagnostic evaluations (e.g., repeat bone marrow aspirations, multiple-course chemotherapies, “second-look” operations) rather than a single treatment effort. The absence of a main effect for ICR in Part 2 on the anxiety and mood measures indicated that patients felt in general that they had as difficult a course during the second implant as with the first. In contradiction to the patients’ self-reports, physicians judged the patients as better adjusted after their second ICR treatment. These evaluations may reflect the belief that patients “adapt” and that a patient’s attitude toward her illness, treatment and recovery “should” be substantially more positive after the conclusion of her treatment. As well, when visited briefly by their physician, patients may have minimized their distress that they reported on the questionnaires. Considering the patient data alone, however, we suggest that these cancer patients, as others, do not adapt, and the lengthy, anxiety-producing, and fatiguing aspects of ICR remain as noxious for the second as for the first treatment.

In many investigations of medical treatment anxiety, level of pretreatment anxiety directly predicted post-treatment anxiety (e.g., Auerbach, 1973; Spielberger et al., 1973). However, in studying the responses of cancer patients, we found an interaction between Pre-treatment Anxiety Level and Time in Part 1, and Anxiety Level, Time, and Repeated Treatments in Part 2. In the present investigation those professing low anxiety initially underwent considerable disruption subsequently — increased anxiety, more disruption in their activity levels, and more discomfort during the ICR. Which level of anxiety is more adaptive in the context of cancer and treatment-specific anxiety remains to be determined, although Janis (1958) much earlier suggested more complicated post-operative outcomes for those professing low pretreatment anxiety. While the present data require replication due to the small sample sizes when analyzing the factor of Pre-treatment Anxiety Level, they may be illustrative of unique psychological response patterns of individuals such as cancer patients who are under extraordinarily stressful life conditions or chronic threats.

In addition to self-reported state anxiety and a physiological indicant, other measures were used to document patient distress and adjustment. The POMS revealed significant differences with time, with patients reporting increased fatigue, and decreased activity following each ICR. This finding documents the debilitating nature of lengthy radiotherapy. In view of the findings with the STAI, it is somewhat surprising that no differences were found with the Tension-Anxiety scale of the POMS. Previous study of the factor structure of the STAI indicates that for the state scale there are primarily two factors, one reflecting “negative descriptors” and the other reflecting “positive descriptors” (Kendall, Finch, Auerbach, Hooke, & Mikulka, 1976). Many of the items that load on the negative descriptor factor are identical or similar to those items on the POMS Tension-Anxiety scale. Thus, the state anxiety findings in the present investigation reflect not only the presence of negative affective states but the absence of offsetting positive ones. Patients reporting low vs. high pre-treatment anxiety were not differentiated with the nurses’ recordings of the patients’ moods, complaints, or requests. Unfortunately, the limited contact with the patients imposed for radiation protection reasons may have prevented the nurses from gaining sufficient information to detect differences between groups.

These data are preliminary, requiring replication since this treatment has never been studied systematically and the sample sizes were smaller than those typically used. However, several findings of theoretical and clinical importance emerged from the present investigation. First, internal radiation therapy can produce significant anxiety, physiological arousal, discomfort, and fatigue for cancer patients. Second, in contrast to the decline in anxiety that noncancer medical patients report at the conclusion of a diagnostic procedure or during recovery, these cancer patients report continued or even in-creased anxiety. Third, it appears that these cancer patients may not adapt to the stresses of ICR. Finally, individual differences among cancer patients in their level of pretreatment anxiety may influence subsequent outcome, and interact with an individual’s experience with the medical stressor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a Biomedical Research Grant NIHSO7-RR07035-16 awarded to the first author and based on a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the M. A. degree for the second author.

The authors would like to thank individuals who provided assistance. Greatest appreciation is extended to the participating patients. In addition, the following assisted: Resident physicians from the Departments of Obstetrics-Gynecology and Radiology and George Chapman, M.D.; Susan Guenther, Ed.D.; nurses Jeanette Peck, Mari Rude, and Jan See; research assistant Suzanne Kell; and secretaries Becky Huber and Valerie Olson. Professors Elizabeth Altmaier, John Cacioppo, Neville Hacker, John Knutson, and Donald Routh and Michael Ellifson provided helpful comments.

Footnotes

Early research examining surgery and recovery experiences from the patient’s perspective is credited to Irving Janis (1958). He classified patients into low, moderate, and high pre-operative anxiety groups and proposed that this initial level of anxiety would be related to post-operative outcome in a curvilinear manner. Since the present investigations focus only on low and high pretreatment anxiety classifications and support of the curvilinear pattern has been mixed, another model was chosen for analysis.

Another strategy for creating the low and high pre-treatment anxiety groups for Part 2 would be to use the cutoff score from Part 1. This was not done for statistical and conceptual reasons. First, use of 41 rather than 45 would have resulted in substantial differences in cell sizes between the groups. Second, and perhaps as important, we reasoned that the pre-treatment anxiety level for the first treatment might be different (and perhaps higher) for those women who were to undergo two treatments rather than one. If so, subjects might be inappropriately assigned to anxiety groups (e.g., receiving “high” anxiety group assignment when they were reporting a “low” anxiety level, in the context of women who receive two treatments).

REFERENCES

- Andersen BL, Hacker NF. Treatment for gynecologic cancer: A review of the effects on female sexuality. Health Psychology. 1983;2:203–221. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.2.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BL, Tewfik HH. Individual differences in psychological responses to radiation therapy: A reconsideration of the adaptive aspects of anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.4.1024. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach SM. Trait-state anxiety and adjustment to surgery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;40:264–271. doi: 10.1037/h0034538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JR. Social support, accommodation to stress and adjustment to breast cancer. Social Science and Medicine. 1982;16:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen F, Lazarus R. Active coping processes, coping dispositions, and recovery from surgery. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1973;35:375–389. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Abeloff MD, Melisaratos N. Psychological coping mechanisms and survival time in metastatic breast cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1979;242:1504–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, Schmale AM, Henrichs M, Carnicke CL. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1983;249:751–757. doi: 10.1001/jama.249.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. Heart rate as an index of anxiety: Failure of a hypothesis. In: Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, editors. Perspectives in cardiovascular psychophysiology. New York: Guilford Press; 1982. pp. 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman D, Lewis M. Differences in crisis reactions among cancer and surgery patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:381–388. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janis I. Psychological stress: Psychoanalytic and behavioral studies of surgical patients. New York: Wiley; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Dabbs J, Leventhal H. Psychosocial factors in the welfare of surgical patients. Nursing Research. 1970;19:18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Leventhal H, Dabbs J. Contributions of emotional and instrumental response processes in adaptation to surgery. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1971;20:55–64. doi: 10.1037/h0031730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Carpenter L. Relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative state. Psychological Medicine. 1980;10:361–367. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700044135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM, Atkins CJ, Lenhard L. Coping with a stressful sigmoidoscopy: Evaluation of cognitive and relaxation preparations. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1982;5:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00845257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Finch AJ, Auerbach SM, Hooke JF, Mikulka PJ. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: A systematic evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1976;44:406–412. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.44.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall P, Williams L, Pechacek T, Graham L, Shisslak C, Herzoff N. Cognitive-behavioral and patient education interventions in cardiac catheterization procedures : The Palo Alto medical psychology project. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucente FE, Fleck S. A study of hospitalization anxiety in 408 medical and surgical patients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1972;34:304–312. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalit C, Teichman Y, Levitt R. Emotional reactions to physical threat: Reexamination with female subjects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1980;48:403–404. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Urrutia A. Anxiety and pain in surgical patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1975;43:437–442. doi: 10.1037/h0076898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, Ridgeway V. Personality and surgical recovery: A review. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1981;20:243–260. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1981.tb00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. Manual for the profile of mood states. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Newall J. Who treats cervical cancer? International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, and Physics. 6:1271–1272. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(80)90184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck A, Boland J. Emotional reactions to radiation treatment. Cancer. 1977;40:180–184. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197707)40:1<180::aid-cncr2820400129>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CA, Knapp RC, Young RC. Gynecologic tumors. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: Principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott; 1982. pp. 823–883. [Google Scholar]

- Redd W, Andrykowski M. Behavioral intervention in cancer treatment: Controlling aversive reactions to chemotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:1018–1029. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.6.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotman M, Rogow L, DeLeon G, Heskel N. Supportive therapy in radiation oncology. Cancer. 1977;39:744–750. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197702)39:2+<744::aid-cncr2820390709>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley R, Butt J, Horwitz E. Preparation to re-experience a stressful medical examination: Effect of repetitious videotape exposures and coping style. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:485–492. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, McNamara J. Social work services for radiation therapy patients and their families. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1977;28:752–754. doi: 10.1176/ps.28.10.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C, Auerbach S, Wadsworth A, Dunn T, Taulbee E. Emotional reactions to surgery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;40:33–38. doi: 10.1037/h0033982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon DT, Bigelow DA. Effect of information about a potentially stressful situation on responses to stress impact. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1974;29:50–59. doi: 10.1037/h0035711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch DA. Assessment of nausea and vomiting in cancer patients undergoing external beam radiotherapy. Cancer Nursing. 1980;23:365–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonke G. Emotional responses to radiotherapy. Hospital Topics. 1967;2:107–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]