Abstract

The ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport) machinery is required for the scission of membrane necks in processes including the budding of HIV-1, and cytokinesis. An essential step in cytokinesis is recruitment of the ESCRT-I complex and the ESCRT associated protein ALIX to the midbody (the structure that tethers two daughter cells) by the protein CEP55. Biochemical experiments show that peptides from ALIX and the ESCRT-I subunit TSG101 compete for binding to the ESCRT and ALIX binding region (EABR) of CEP55. A 2.0 Å crystal structure of EABR bound to an ALIX peptide shows that EABR forms an aberrant dimeric parallel coiled-coil. Bulky and charged residues at the interface of the two central heptad repeats create asymmetry and a single binding site for an ALIX or TSG101 peptide. Both ALIX and ESCRT-I are required for cytokinesis, suggesting that multiple CEP55 dimers are required for function,

Cytokinesis, the division of the cytoplasm, is the final step of the M phase of the cell cycle. Cytokinesis begins with the formation of the contractile ring, which drives the growth of the cleavage furrow. Vesicle trafficking components, including the exocyst complex and SNAREs, deliver the additional membrane needed for the cleavage furrow to grow (1-3). When the extension of the furrow ends, the contractile ring disassembles, and a structure known as the midbody remains as the final tether between the two daughter cells. The last step in cytokinesis, the cleavage of the plasma membrane at the midbody, is referred to as abscission. The mechanism of abscission became clearer with the discovery that the midbody protein CEP55 (4-6) recruits two key components of the ESCRT machinery (7-11), the ESCRT-I complex and ALIX (12, 13). The role of ALIX and ESCRT-I in abscission appears to be to recruit ESCRT-III subunits, which are required for normal midbody morphology (14) and are widely believed to have a membrane scission activity (15).

Deletion analysis of ALIX mapped the interaction with CEP55 to a putative unstructured Pro-rich sequence near its C-terminus (12,13). Similarly, the TSG101 subunit of ESCRT-I interacts via an unstructured linker between its ubiquitin-binding UEV domain and the region that forms the core complex with other ESCRT-I subunits (12,13). CEP55 is a predominantly coiled-coil protein that otherwise lacks familiar protein:protein interaction domains. The predicted coiled-coil of CEP55 is interrupted near the middle by a ∼60 residue region that has been suggested to serve as a hinger between the N- and C-terminal coiled coil regions (13). Remarkably, this putative hinge region is also the locus for binding to the putative unstructured Pro-rich regions of ALIX and TSG101. Because it is very unusual for two unstructured regions from two different proteins to drive specific contacts between them, we pursued a more detailed deletion analysis (Fig. S1) with the aim of characterizing binding constants, stoichiometry, and structural basis of the interaction.

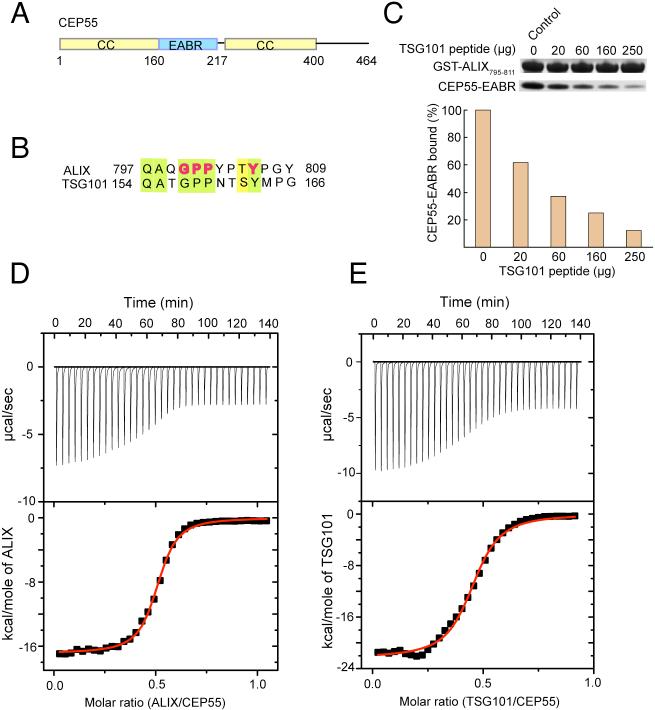

The CEP55 fragment EABR containing residues 160−217 (Fig. 1A, S1) bound to a 13-residue peptide based on the Pro-rich sequence of ALIX (residues 797−809) (Fig. 1B) with a dissociation constant Kd = 1 μM and a stoichiometry of 2:1 (Fig. 1D). The EABR binds to the related TSG101 peptide (residues 154 to 166) with essentially the same affinity and stoichiometry (Fig. 1E). Various CEP55-EABR to peptide stoichiometric mixtures were subjected to analytical ultracentrifugation (Fig. S2-S4). A 2:1 EABR:ALIX mixture showed the presence of a single complex, whereas all mixtures having a higher proportion of peptide resulted in both the 2:1 complex, as well as excess free peptide. Similarly, a peptide derived from the Pro-rich region of TSG101 forms a 2:1 CEP55:peptide complex (Fig. S2). When the TSG101 peptide was added to a preformed 2:1 CEP55:ALIX peptide complex, a peak corresponding to the equivalent amount of uncomplexed peptide is formed, suggesting that TSG101 and ALIX compete for the same site (Fig. S2, bottom panel). Competitive binding experiments (Fig. 1C) confirmed that the two peptides interact with the same site.

Figure 1. The CEP55 ESCRT-I and ALIX binding region and its interactions.

(A) Predicted coiled-coil regions (yellow) and the EABR of CEP55 (blue). The region designated EABR corresponds to the region formerly suggested to be a hinge between the N- and C-terminal coiled coils (13). (B) CEP55 binding sequences of ALIX and the ESCRT-I subunit TSG101, with conserved residues highlighted with light green shading, and residues shown to be functionally important in ALIX highlighted in bold red type. (C) Pull-down of CEP55-EABR by the GST-ALIX fragment shown, in the presence of the indicated amounts of TSG101 peptide competitor. (D) ITC titration of ALIX peptide into CEP55-EABR solution. (E) ITC titration of TSG101 peptide into CEP55-EABR solution.

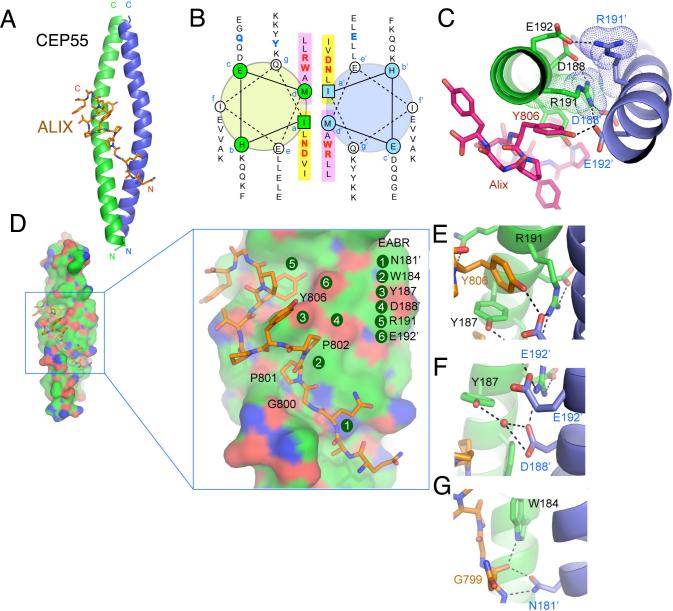

To gain further insight into the structural organization of ESCRTs at the midbody, we determined the 2.0 Å resolution structure of the CEP55 EABR bound to the ALIX peptide (Fig. 2A, S5; Table S1). The EABR forms a parallel coiled coil over its entire length, comprising a total of six heptad repeats (Fig. 2B). In the two heptad repeats closest to the N- and C-termini, respectively, there is canonical hydrophobic packing between the two coils. In the two central heptad repeats (repeats 3 and 4), in contrast, there are several non-standard interactions between the coils (Fig. 2A). In repeat 3, the a position is occupied by Asn181, and the d position by Trp184 (Fig. 2B). In repeat 4, Asp188 and Arg191 occupy these two positions. Asp and Arg occur at the a and d positions, respectively, of coiled coils with less than one percent of their overall frequency in GenBank (16). The effect of placing four disfavored polar and/or bulky residues at both the a and d positions of adjacent heptad repeats is two-fold. First, the two coils are pushed up to 9 Å apart (Fig. S6), compared to 6 Å for canonical parallel dimeric coils (17). Second, to avoid steric overlap and electrostatic repulsion, the structure becomes asymmetric (Fig. 2C). By pushing apart the two coils in an asymmetric manner, the four non-canonical a and d position residues create a single binding site for the ALIX peptide.

Figure 2. Structure of the non-canonical CEP55-EABR coiled coil and its complex with ALIX.

(A) The overall structure of the CEP55-EABR homodimer (green and blue ribbons) in complex with the ALIX peptide (stick model, carbon orange, oxygen red, nitrogen blue). At right, the intercoil Cα-Cα distance at the a and d positions of the coiled-coil is shown as a function of residue number for CEP55 (red curve) as compared to the average Cα-Cα distance at the a and d positions of the GCN4 leucine zipper (blueline). (B) Helical wheel analysis of the six heptad repeats of the EABR coiled coil. (C) Charge repulsion between Asp188, Arg191, and Glu192 pairs in the homodimer creates asymmetry in the coiled coil and interactions with the ALIX peptide. (D) Overview and close-ups of selected regions of the CEP55 surface (carbon green, oxygen red, nitrogen blue), with the ALIX peptide colored as in (A). (E-G) Molecular interactions in the complex shown in detail and colored as in (A).

The ALIX peptide interacts with CEP55-EABR via its GPP sequence (Gly800-Pro802) and Tyr806. The peptide conformation is kinked between the GPP and Tyr806, and wraps around the protruding side-chain of CEP55 Tyr187 (Fig. 2D, E). CEP55 Tyr187 is essential for the ALIX interaction (Fig. 3A). The GPP sequence makes extensive contacts with CEP55 Trp184 and Tyr187, and the aliphatic portions of the Lys180 and Gln183 side-chains (Fig. 2D-G). Mutation of CEP55 residues Trp184 or Tyr187 reduces binding to essentially undetectable levels (Fig. 3A). Within the GPP sequence, Pro801 makes the most extensive contacts of the three residues of the GPP motif, and its mutation to Ala reduces binding by ∼60-fold (Fig. 3B). The Gly and the second Pro make correspondingly smaller, but still significant contributions to specificity (Fig. 3B). The second major point of contact involves ALIX Tyr806, which wedges its ring between CEP55 Tyr187 and Trp184, and forms a short, strong hydrogen bond between its hydroxyl and the side-chain of Glu192’ (Fig. 2E, F). Mutation of Glu192 reduces binding by ∼30-fold (Fig. 3A), while mutation of ALIX Tyr806 almost completely abolishes binding (Fig. 3B).

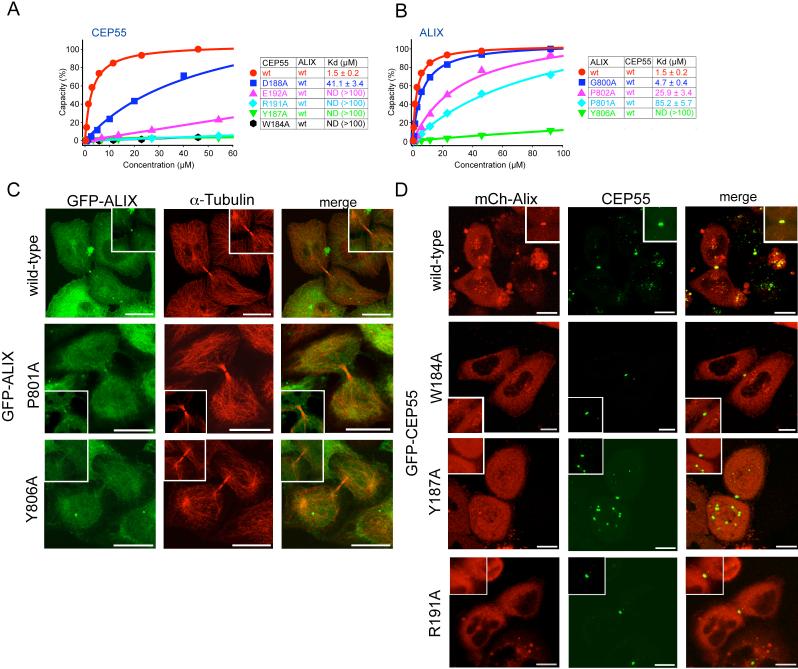

Figure 3. Point mutations in CEP55 and ALIX abrogate binding and cellular localization.

(A) SPR analysis of wild-type and mutant CEP55-EABR mutants binding to wild-type ALIX fragment. Binding curves are colored according to affinity in the order red > blue > pink > cyan > green > black in (A) and (B). (B) SPR analysis of wild-type and mutant ALIX fragment binding to wild-type CEP55 EABR. (C) Midbody localization of wild-type and mutant GFP-ALIX expressed in HeLa cells. A magnification of the midbody region is shown in the insets. α−tubulin staining was used (middle panel) to highlight the midbody microtubule structure. (D) Live cell imaging of midbody localization of wild-type mCh-ALIX and wild-type or mutant CEP55 coexpressed in HeLa cells. CEP55 midbody localization was not affected in the mutant (Fig. S7). Insets show higher magnification of the midbody region. Scale bar = 10 μm.

To evaluate the effect of interfering with ALIX-CEP55 interactions on the subcellular localization of ALIX, full-length ALIX mutants were tagged with GFP and their localization compared to wild-type ALIX. While wild-type ALIX strongly localized to midbodies (Fig. 3C, top row) (12, 13), ALIXP801A, which had weaker binding affinity in vitro, had reduced midbody localization (Fig. 3C, row 2). Notably, ALIXY806A, which completely blocks binding in vitro, showed no midbody localization above background (Fig. 3C, bottom row). The magnitude of the effect of mutating the ALIX GPPX3Y motif on localization thus correlates well with the effects on in vitro binding and with the structure. To further understand the relationship between ALIX and CEP55 in cells, a series of GFP-CEP55 mutants at the corresponding binding residues were tested. While the localization of CEP55 to midbodies was not affected in any of the mutants (Fig. S7), ALIX localization appeared to be impaired. Specifically, cells cotransfected with wild-type mCh-ALIX and any of the CEP55 mutants W184A, Y187A, and R191A showed severely impaired midbody localization of mCh-ALIX compared to wild-type CEP55 (Fig. 3D). This shows that the integrity of the CEP55 EABR is important for ALIX to target to this structure. When mCh-TSG101 was cotransfected with CEP55 mutants (Fig. S8), a similar CEP55 dependence for TSG101 midbody localization was observed. Taken together, the cellular results strongly corroborate that the interfacial residues observed in both ALIX and CEP55 are responsible for the physiological localization of ALIX by CEP55. Furthermore, the localization of TSG101 is shown to be controlled in cells by the same key EABR residues in CEP55 as for ALIX.

The ESCRT machinery directs a conserved membrane cleavage reaction that is important in multiple cellular processes. At the endosome, the ESCRTs have a dual function in cargo sorting and membrane budding. ESCRTs are targeted to endosomes by multiple low affinity (Kd > 100 μM) interactions with ubiquitinated membrane proteins and micromolar interactions with 3-phosphoinositides (7-11). Viruses such as HIV-1, in contrast, appear to self-organize into buds, and require the ESCRTs for their final scission from the plasma membrane of the host cell (18-20). In viral budding, ESCRT targeting is mediated primarily by micromolar (Kd ∼ 5−30 μM) affinity interactions with PTAP and YPXL motifs and ESCRT-I (21) and ALIX (22, 23), respectively. ESCRT targeting to the midbody appears more similar to the situation in viral as opposed to endosomal budding, in that a single, highly specific micromolar binary interaction between GPPX3Y motifs and CEP55-EABR is key to recruitment. These observations are consistent with a model in which the ESCRTs have a broad-based modular membrane scission activity targeted via the recognition of short peptide motifs, in addition to their endosome-specific, ubiquitin-directed ability to cluster cargo.

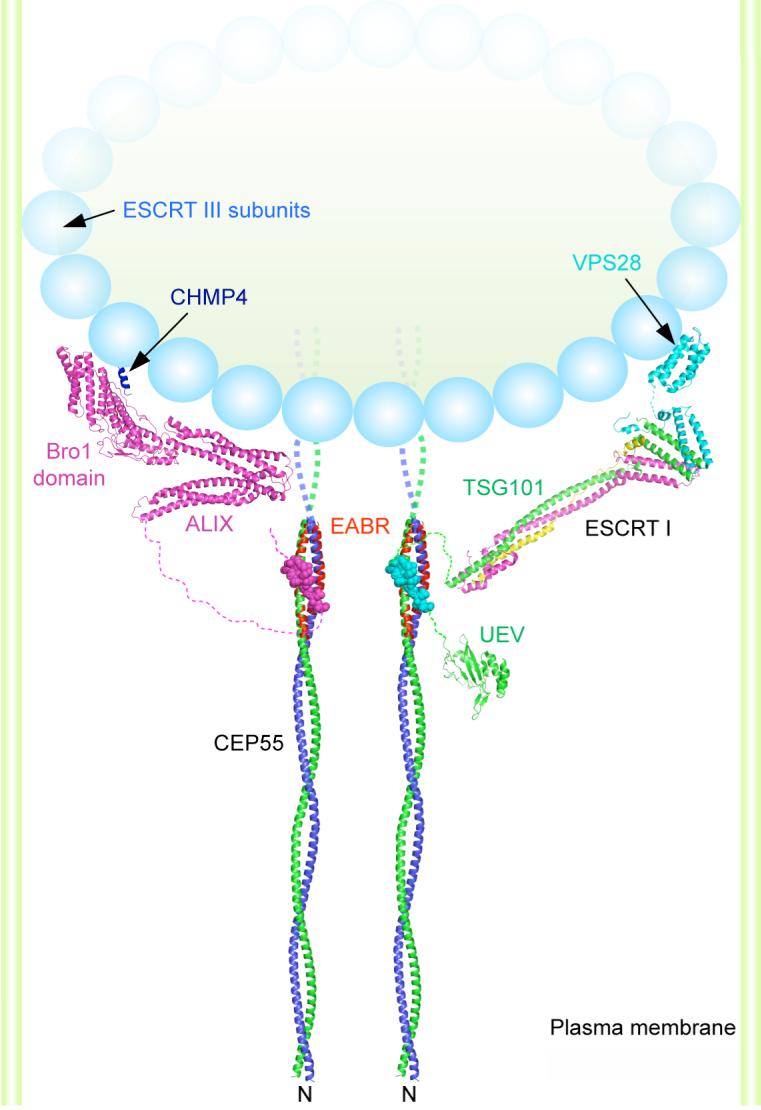

In a working model for cleavage of the membrane neck, ESCRT-I and ALIX recruit ESCRT-III components, which are also found at the midbody (13). ESCRT-III forms a circular array that is an attractive candidate to drive the closure and cleavage of the membrane neck (15). Indeed, an ALIX allele defective in binding the ESCRT-III subunit CHMP4 does not support cytokinesis (14). Both ESCRT-I and ALIX are needed for cytokinesis, at least in HeLa cells (12, 13). Our finding that one CEP55 dimer binds to only one copy of ALIX or ESCRT-I indicates that multiple CEP55 dimers are required for function, which suggests that the nucleation of ESCRT-III assembly occurs at a minimum of two sites. The striking and unexpected finding that the region previous thought to form a hinge between the N-terminal and C-terminal coiled coils is, in fact, itself in a coiled-coil conformation and is probably contiguous with the N-terminal coiled coil provides tight constraints on possible models for the organization of CEP55 within the midbody. A possible model that incorporates the characterization of the CEP55-EABR:ALIX complex and related crystallographic (24-26) and electron microscopic analyses (15) is shown in figure 4. While much remains to be learned about the molecular architecture of the midbody and the precise stereochemistry of cytokinesis, the results and model presented here provide one foothold for furthering such an understanding..

Figure 4. A model for the organization of CEP55-ESCRT and CEP55-ALIX complexes in the midbody.

Model of the N-terminal half of the CEP55 structure docked to the ESCRT-I core (24) and UEV domain(21) and ALIX(25) structures as described in the on line methods supplement. The crystallized EABR portion of the CEP55 coiled coil is highlighted in red. The structure of the C-terminal domain of the yeast Vps28 subunit of ESCRT-I is shown (27) as a putative binding site for Vps20, the yeast ortholog of the human ESCRT-III subunit CHMP6. The binding site on the Bro1 domain of ALIX for the C-terminal helix (blue) of the CHMP4 subunit of ESCRT-III is shown (26, 28). A schematic of an ESCRT-III circular array (15) is shown. The width of the membrane neck is not to scale.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The ESCRT machinery, which is required for membrane abscission in cytokinesis, is targeted to the midbody by a coiled-coil in CEP55 that is built around an unusual charged core.

References and Notes

- 1.Glotzer M. Science. 2005;307:1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1096896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr FA, Gruneberg U. Cell. 2007;131:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prekeris R, Gould GW. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1569–1576. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao WM, Seki A, Fang GW. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:3881–3896. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Garay I, Rustom A, Gerdes HH, Kutsche K. Genomics. 2006;87:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabbro M, et al. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slagsvold T, Pattni K, Malerod L, Stenmark H. Trends In Cell Biology. 2006;16:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RL, Urbe S. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:355–368. doi: 10.1038/nrm2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nickerson DP, Russell DW, Odorizzi G. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:644–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saksena S, Sun J, Chu T, Emr SD. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurley JH. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008;20:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlton JG, Martin-Serrano J. Science. 2007;316:1908–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1143422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morita E, et al. Embo J. 2007;26:4215–4227. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlton JG, Agromayor M, Martin-Serrano J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10541–10546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802008105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanson PI, Roth R, Lin Y, Heuser JE. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:389–402. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupas A, Vandyke M, Stock J. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oshea EK, Klemm JD, Kim PS, Alber T. Science. 1991;254:539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1948029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morita E, Sundquist WI. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:395–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.102350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bieniasz PD. Virology. 2006;344:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujii K, Hurley JH, Freed EO. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2007;5:912–916. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pornillos O, Alam SL, Davis DR, Sundquist WI. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:812–817. doi: 10.1038/nsb856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munshi UM, Kim J, Nagashima K, Hurley JH, Freed EO. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3847–3855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhai Q, et al. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2008;15:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostelansky MS, et al. Cell. 2007;129:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher RD, et al. Cell. 2007;128:841–852. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mccullough J, Fisher RD, Whitby FG, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7687–7691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pineda-Molina E, et al. Traffic. 2006;7:1007–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J, et al. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:937–947. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.We thank B. Beach for generating DNA constructs, E. Freed and K. Kutsche for providing DNAs, T. Alber for discussions, and the staff of SER-CAT for user support at the APS. Use of the APS was supported by the U. S. DOE, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under Contract No.W-31−109-Eng-38. This research was supported by NIH intramural support, NIDDK (J.H.H.), NICHD (J.L.) and IATAP (J.H.H. and J.L.). Crystallographic coordinates have been deposited in the RCSB protein data bank with accession number 3E1R.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.