Abstract

P-glycoprotein (Pgp) detoxifies cells by exporting hundreds of chemically unrelated toxins but has been implicated in multidrug resistance in the treatment of cancers. Substrate promiscuity is a hallmark of Pgp activity, thus a structural description of polyspecific drug-binding is important for the rational design of anticancer drugs and MDR inhibitors. The x-ray structure of apo-Pgp at 3.8 Å reveals an internal cavity of ∼6,000 Å3 with a 30 Å separation of the two nucleotide binding domains (NBD). Two additional Pgp structures with cyclic peptide inhibitors demonstrate distinct drug binding sites in the internal cavity capable of stereo-selectivity that is based on hydrophobic and aromatic interactions. Apo- and drug-bound Pgp structures have portals open to the cytoplasm and the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer for drug entry. The inward-facing conformation represents an initial stage of the transport cycle that is competent for drug binding.

The American Cancer Society reported over 12 million new cancer cases and 7.6 million cancer deaths worldwide in 2007 (1). Many cancers fail to respond to chemotherapy by acquiring MDR, to which has been attributed the failure of treatment in over 90% of patients with metastatic cancer (2). Although MDR can have several causes, one major form of resistance to chemotherapy has been correlated with the presence of at least three molecular “pumps” that actively transport drugs out of the cell (3). The most prevalent of these MDR transporters is P-glycoprotein (Pgp), a member of the ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) Superfamily (4). Pgp has unusually broad poly-specificity, recognizing hundreds of compounds as small as 330 Da up to 4,000 Da (5, 6). Most Pgp substrates are hydrophobic and partition into the lipid bilayer (7, 8). Thus, Pgp has been likened to a molecular “hydrophobic vacuum cleaner” (9), pulling substrates from the membrane and expelling them to promote MDR.

While the structures of bacterial ABC importers and exporters have been established (10-15) and Pgp characterized at low resolution by electron microscopy (16, 17), obtaining an x-ray structure of Pgp is of particular interest because of its clinical relevance. We describe the structure of mouse Pgp that has 87% sequence identity to human Pgp (Fig. S1) in a drug-binding competent state. We also determined co-crystal structures of Pgp complexed with two stereo-isomers of cyclic hexapeptide inhibitors, cyclic-tris-(R)-valineselenazole (QZ59-RRR) and cyclic-tris-(S)-valineselenazole (QZ59-SSS), revealing a molecular basis for poly-specificity.

Mouse Pgp protein exhibited typical basal ATPase activity that was stimulated by drugs like verapamil and colchicine (Fig. S2A) (18). Apo-Pgp recovered from washed crystals retained near full ATPase activity (Fig. S3). Both QZ59 compounds inhibited the verapamil-stimulated ATPase activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S2B). Both stereo-isomers inhibited calcein-AM export with IC50 values in the low micromolar range (Fig. S4) and increasing doses of QZ59 compounds resulted in greater colchicine sensitivity in Pgp-overexpressing cells (Fig. S5).

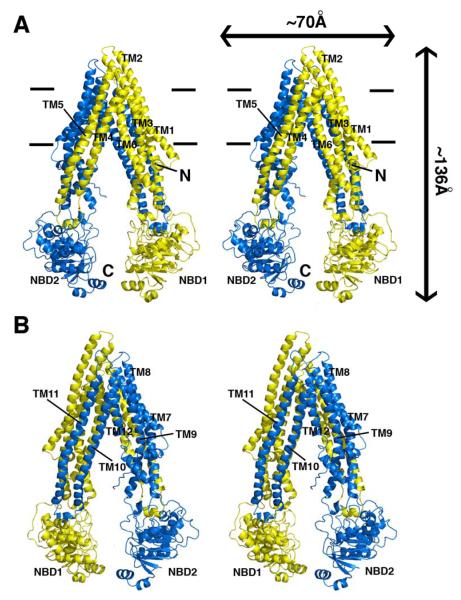

The structure of Pgp (Fig. 1) represents a nucleotide-free inward-facing conformation arranged as two “halves” with pseudo two-fold molecular symmetry spanning ∼136 Å perpendicular to and ∼70 Å in the plane of the bilayer. The nucleotide binding domains (NBDs) are separated by ∼30 Å. The inward facing conformation, formed from two bundles of six helices (TMs 1-3,6,10,11 and TMs 4,5,7-9,12), results in a large internal cavity open to both the cytoplasm and the inner leaflet. The model was obtained as described in Supplemental Text using experimental electron density maps (Fig. S6,S7,and Table S1), verified by multiple Fo-Fc maps (Fig. S8-S10), with the topology confirmed by CMNP labeled cysteines (Fig. S6B-D,S7C,S11, and Table S2). Two portals (Fig. S12) allow access for entry of hydrophobic molecules directly from the membrane. The portals are formed by TMs 4/6 and 10/12, each of which have smaller sidechains that could allow tight packing during NBD dimerization (Table S3). At the widest point within the bilayer, the portals are ∼9 Å wide and each are formed by an intertwined interface in which TMs 4/5 (and 10/11) cross over to make extensive contacts with the opposite α-helical bundle (Fig. 1). Each intertwined interface buries ∼6,900 Å2 to stabilize the dimer interface and is a conserved motif in bacterial exporters (13, 14). The structure is consistent with previous crosslinking studies that identified residue pairs in the intertwined interface (Fig. S13). The volume of the internal cavity within the lipid bilayer is substantial (∼6,000 Å3) and could accommodate at least two compounds simultaneously (19). The presumptive drug binding pocket comprises mostly hydrophobic and aromatic residues (Table S3). Of the 73 solvent accessible residues in the internal cavity, 15 are polar and only two (His60 and Glu871), located in the N-terminal half of the TMD, are charged or potentially charged. In this crystal form, two Pgp molecules (PGP1 and PGP2) are in the asymmetric unit and are structurally similar, with the only appreciable differences localized in the NBDs and the four short intracellular helices (IH1-4) that directly contact the NBDs (Fig. S14).

Fig. 1.

Structure of Pgp. (A) Front and (B) back stereo views of PGP. TM1-12 are labeled. The N- and C-terminal half of the molecule is colored yellow and blue, respectively. TM4-5 and TM10-11 cross over to form intertwined interfaces that stabilize the inward facing conformation. Horizontal bars represent the approximate positioning of the lipid bilayer. The N- and C-termini are labeled in panel A. Transmembrane (TM) domains and nucleotide binding domains (NBD) are also labeled.

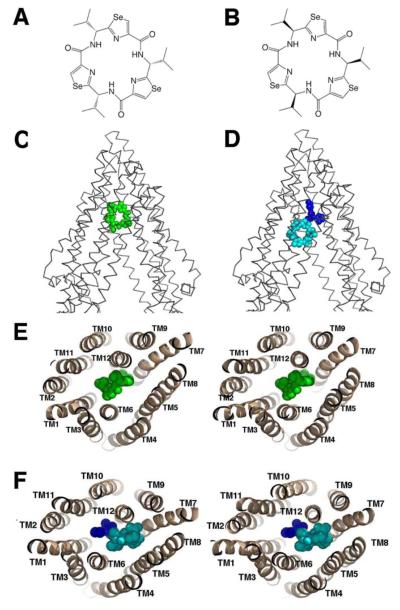

Pgp can distinguish between the stereo-isomers of cyclic peptides (Fig. 2A-B) resulting in different binding locations, orientation and stoichiometry. QZ59-RRR (Fig. 2A) binds one site per transporter located at the center of the molecule between TM6 and TM12 (Fig. 2C and 2E). The binding of QZ59-RRR to the “middle” site is mediated by mostly hydrophobic residues on TMs 1,5,6,7,11, and 12 (Table S3). QZ59-SSS (Fig. 2B) binds two sites per Pgp molecule (Fig. 2D and 2F). The QZ59-SSS molecule occupying the “upper” site is surrounded by hydrophobic aromatic residues on TMs 1,2,6,7,11, and 12 (Table S3) and a portion of this ligand is disordered in both PGP1 and PGP2 (Fig. S15). The ligand in the “lower” site that binds to the C-terminal half of the TMD is in close proximity to TMs 1,5,6,7,8,9,11, and 12 and surrounded by three polar residues (Gln721, Gln986, and Ser989).

Fig. 2.

Binding of novel cyclic peptide Pgp inhibitors. Chemical structures of (A) QZ59-RRR and (B) QZ59-SSS. (C) Location of one QZ59-RRR (green spheres) and (D) two QZ59-SSS (blue and cyan spheres) molecules in the Pgp internal cavity. (E-F) Stereo images showing interaction of transmembrane helices with QZ59 compounds viewed from the intracellular side of the protein looking into the internal chamber. In both cases the compound(s) are sandwiched between previously identified drug binding TMs 6 and 12. The location of the QZ59 compounds was verified by anomalous Fourier (Fig. S15B-C) and Fo-Fc maps (Fig. S15D-E and S16-S17).

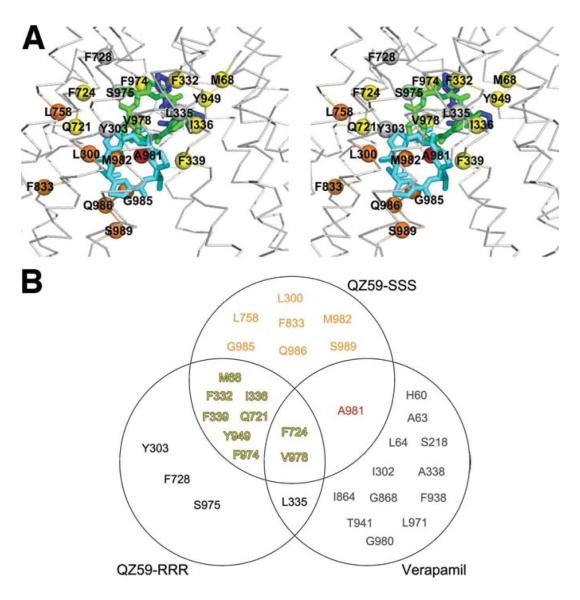

The co-crystal structures of Pgp with QZ59 compounds demonstrate that the inward facing conformation is competent to bind drugs. Previous studies have identified residues that interact with verapamil (Fig. S1) (20, 21). Many of these residues face the drug binding pocket (Fig. 3A,S15,S16,Table S3) and are highly conserved (Fig. S1), suggesting a common mechanism of poly-specific drug recognition. For QZ59-RRR and both QZ59-SSS molecules, the isopropyl groups point in the same direction, toward TM9-12 (Fig 3A). Although certain residues in Pgp contact both QZ59 compounds, the specific functional roles of the residues binding each inhibitor are different (Fig. S17). For example, F332 contacts the molecules in the “upper” but not “lower” sites of QZ59-SSS but does contact the inhibitor in the “middle” (QZ59-RRR) site (Fig. S17C and J). F724 is near both the “middle” (Fig. S17E) and “lower” (Fig. S17M) sites, but is much closer to a selenium atom in QZ59-SSS. V978 plays an important role having close proximity to all three QZ59 sites (Fig. S17H and N). Interestingly, both F724 (human F728) and V978 (human V982) are protected from MTS labeling by verapamil (20, 21)(Fig. 3B, S1 and S18), indicating both are important for drug binding. While the upper half of the drug binding pocket contains predominantly hydrophobic/aromatic residues, the lower half of the chamber has more polar and charged residues (Fig. S19). Hydrophobic substrates that are positively charged may bind using these residues similar to the poly-specific drug binding pockets of QacR and EmrE that use residues like glutamate to neutralize different drugs (22, 23).

Fig. 3.

Drug binding residues of Pgp. (A) Stereo view of the drug-binding cavity. Cα trace shown in gray. The QZ59-SSS in the “lower” (cyan) and “upper” (blue), as well as QZ59-RRR occupying the “middle” site (green) are superimposed. Residues within ∼4-5 Å of QZ59 compounds are shown as spheres. Spheres colored orange and red represent residues that only contact QZ59-SSS in the “lower” and “upper” site, respectively. Residues in common between QZ59-RRR and QZ59-SSS sites are colored yellow. Four residues (grey spheres) are close to QZ59-RRR but neither QZ59-SSS molecules. (B) Venn diagram of residues in close proximity to QZ59 molecules and residues that are protected from MTS labeling by verapamil binding (Fig. S1) (20, 21). Only residues in contact with the model for QZ59-SSS are displayed. Verapamil-only interacting residues are omitted from (A) for clarity and shown in Fig. S16.

The drug binding pocket of Pgp is nearly six times larger than BmrR (YvcC) and hPXR and differs significantly from AcrB, wherein drug binding is mediated by residues from β-sheets on the extracellular side of the inner cell membrane (24-26). For Pgp, along with the permeases from the three H+/drug antiporter families (MATE, SMR, and MFS), the drug binding site resides in the cell membrane and is formed by TM helices. Extraction of drug directly from the cytoplasm/lipid bilayer is a common theme (27). In fact, most Pgp substrates readily partition into the plasma membrane and lipids are required for drug-stimulated ATPase activity (28). Pgp is a unidirectional lipid flippase (4), transporting phospholipids from the inner to outer leaflets of the bilayer (29). The inward facing conformation of Pgp (Fig. 1) provides access to an internal chamber through two portals (Fig. S12) that are open wide enough to accommodate hydrophobic molecules and phospholipids. The portals form a contiguous space spanning the width of the molecule that allow Pgp to “scan” the inner leaflet to select and bind specific lipids and hydrophobic drugs prior to transport (Fig. 4). Lipids and substrates may remain together during initial entry into the internal cavity and could explain their requirement in promoting ATPase activity.

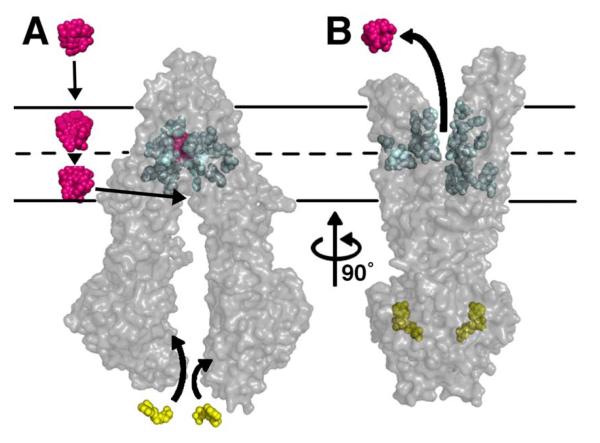

Fig. 4.

Model of substrate transport by Pgp. (A) Substrate (magenta) partitions into the bilayer from outside of the cell to the inner leaflet and enters the internal drug-binding pocket through an open portal. The residues in the drug binding pocket (cyan spheres) interact with QZ59 compounds and verapamil in the inward facing conformation. (B) ATP (yellow) binds to the NBDs causing a large conformational change presenting the substrate and drug-binding site(s) to the outer leaflet/extracellular space. In this model of Pgp, which is based on the outward facing conformation of MsbA and Sav1866 (13, 14), exit of the substrate to the inner leaflet is sterically occluded providing unidirectional transport to the outside.

To accommodate its largest substrates, Pgp may sample even wider conformations in the cell membrane than observed in this crystal form. We were able to soak small hydrophobic heavy metal compounds (ethyl-mercury(II) chloride, 255 Da, and tetramethyl-lead, 267 Da) directly into pre-formed native Pgp crystals, but not QZ59 compounds (660 Da) (Fig. S20). Co-crystals of Pgp with QZ59-RRR and -SSS were only obtained by pre-incubating these compounds with detergent solubilized Pgp prior to crystallization. Taken together, we propose Pgp samples widely open conformations in both detergent-solution and within the membrane to bind larger molecules. Consistent with this hypothesis, a very wide open inward-facing crystal structure of the bacterial homolog of Pgp, MsbA, was previously determined and could accommodate its large substrate, Kdo2-lipid A (MW 2.3 kDa) (14). This large degree of flexibility is also supported by EPR data of MsbA in the lipid membrane (30) as well as the inward facing conformation of other ABC transporters that also have NBDs far apart (31, 32).

The inward-facing structure does not allow substrate access from the outer membrane leaflet nor the extracellular space (Fig. 4A). We propose this conformation represents the molecule in a pre-transport state since we demonstrate drug binding to an internal cavity open to the inner leaflet/cytoplasm. This conformation likely represents an active state of Pgp because protein recovered from crystals had significant drug-stimulated ATPase activity. During the catalytic cycle, binding of ATP, stimulated by substrate, likely causes a dimerization in the NBDs producing large structural changes resulting in an outward facing conformation similar to the nucleotide-bound structures of MsbA or Sav1866 (Fig. 4B). Depending on the specific compound, substrates could either be released as a consequence of decreased binding affinity caused by changes in specific residue contacts between the protein and drug going from the inward to outward facing conformation or, alternatively, facilitated by ATP hydrolysis. In either case, ATP hydrolysis likely disrupts NBD dimerization and resets the system back to inward facing reinitiating the transport cycle (33) (Fig. 4).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. D.C. Rees, I. Wilson, R.H. Spencer, M.B. Stowell, A. Senior, A. Frost, V.M. Unger, C.D. Stout, and P. Wright. Y. Weng was supported by a scholarship from P.R. China. We thank SSRL, ALS, and APS. This work was supported by grants from the Army (W81XWH-05-1-0316), NIH (GM61905,GM078914,GM073197), the Beckman Foundation, the Skaggs Chemical Biology Foundation, Jasper L. and Jack Denton Wilson Foundation, the Southwest Cancer and Treatment Center, and the Norton B. Gilula Fellowship. Coordinates and structure factors deposited to PDB (accession codes 3G5U, 3G60, and 3G61).

References

- 1.The American Cancer Society Homepage [Accessed Sept. 4, 2008];Global Cancer Facts and Figures. 2007 http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/Global_Cancer_Facts_and_Figures_2007_rev.pdf.

- 2.Longley DB, Johnston PG. Journal of Pathology. 2005 Jan;205:275. doi: 10.1002/path.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szakacs G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, Booth-Genthe C, Gottesman MM. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2006 Mar;5:219. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharom FJ. Pharmacogenomics. 2008 Jan;9:105. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramachandra M, et al. Biochemistry. 1998 Apr 7;37:5010. doi: 10.1021/bi973045u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam FC, et al. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001 Feb;76:1121. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottesman MM, Pastan I. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1993;62:385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatlik-Landwojtowicz E, Aanismaa P, Seelig A. Biochemistry. 2006 Mar 7;45:3020. doi: 10.1021/bi051380+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raviv Y, Pollard HB, Bruggemann EP, Pastan I, Gottesman MM. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990 Mar 5;265:3975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Locher KP, Lee AT, Rees DC. Science. 2002 May 10;296:1091. doi: 10.1126/science.1071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollenstein K, Frei DC, Locher KP. Nature. 2007 Mar 8;446:213. doi: 10.1038/nature05626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinkett HW, Lee AT, Lum P, Locher KP, Rees DC. Science. 2007 Jan 19;315:373. doi: 10.1126/science.1133488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson RJP, Locher KP. Nature. 2006 Sep 14;443:180. doi: 10.1038/nature05155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward A, Reyes CL, Yu J, Roth CB, Chang G. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007 Nov 27;104:19005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709388104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldham ML, Khare D, Quiocho FA, Davidson AL, Chen J. Nature. 2007 Nov 22;450:515. doi: 10.1038/nature06264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg MF, Kamis AB, Callaghan R, Higgins CF, Ford RC. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003 Mar 7;278:8294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J-Y, Urbatsch IL, Senior AE, Wilkens S. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008 Feb 29;283:5769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lerner-Marmarosh N, Gimi K, Urbatsch IL, Gros P, Senior AE. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999 Dec 3;274:34711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003 Oct 10;278:39706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loo TW, Clarke DM. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997 Dec 19;272:31945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.31945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Biochemical Journal. 2006 Oct 15;399:351. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumacher MA, Brennan RG. Molecular Microbiology. 2002 Aug;45:885. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y-J, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007 Nov 27;104:18999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709387104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheleznova EE, Markham PN, Neyfakh AA, Brennan RG. Cell. 1999 Feb 5;96:353. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watkins RE, et al. Science. 2001 Jun 22;292:2329. doi: 10.1126/science.1060762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami S, Nakashima R, Yamashita E, Yamaguchi A. Nature. 2002 Oct 10;419:587. doi: 10.1038/nature01050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapiro AB, Ling V. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1997 Nov 15;250:122. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Callaghan R, Berridge G, Ferry DR, Higgins CF. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1997 Sep 4;1328:109. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosch I, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Wu RL, Furlong ST, Croop J. Biochemistry. 1997 May 13;36:5685. doi: 10.1021/bi962728r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong J, Yang G, McHaourab HS. Science. 2005 May 13;308:1023. doi: 10.1126/science.1106592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chami M, et al. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2002 Feb 1;315:1075. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofacker M, et al. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007 Feb 9;282:3951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tombline G, Muharemagi A, White LB, Senior AE. Biochemistry. 2005 Sep 27;44:12879. doi: 10.1021/bi0509797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.