Abstract

The article by Yao and coworkers in this issue (Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008;39:7–18) reveals that the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP1/WAF1/SDI1 (designated hereafter as p21), which has been linked to cell cycle growth arrest due to stress or danger cell responses, may modulate alveolar inflammation and alveolar destruction, and thus enlightens our present understanding of how the lung senses injury due to cigarette smoke and integrates these responses with those that activate inflammatory pathways potentially harmful to the lung (1). Furthermore, the interplay of p21 and cellular processes involving cell senescence and the imbalance of cell proliferation/apoptosis may provide us with a more logical explanation of how p21, acting as a sensor of cellular stress, might have such potent and wide roles in lung responses triggered by cigarette smoke. Molecular switches, ontologically designed for the protection of the host, are now hijacked by injurious stresses (such as cigarette smoke), leading to organ damage.

A paradigm is essential to the scientific inquiry. (2)

No natural history can be interpreted in the absence of at least some implicit body of intertwined theoretical and methodological belief that permits selection, evaluation, and criticism. (3)

Fundamental research discoveries inevitably drive conceptual shifts that bring us closer to scientific truths. In medicine, this effort translates into better health and living standards. However, as in most if not all branches of human knowledge, these discoveries carry a price. Traditional conceptual frameworks or paradigms cannot always explain newly generated knowledge obtained by experimentation and careful interpretation of scientific data. What once was new and revolutionary now becomes outdated and needs to be readdressed within a new conceptual framework. In fact, the past and the inevitable future clash and, from this dialectic (i.e., conflict of opposites), a new understanding emerges.

The article by Yao and coworkers in this issue of the AJRCMB (pp. 7–18), while exploring well-established paradigms of cigarette smoke–induced lung injury, provides data that support a potential conceptual shift regarding how the lung is damaged by persistent exposure to cigarette smoke (1). This paradigm has evolved based on the resemblance between emphysema and aging lung processes (4), the impact of lung injuries promoted by lifelong exposure to cigarette smoke, and the potential for an autoimmune component of inflammation in advanced stages of the disease (5). The inflammation and protease–antiprotease hypothesis of chronic obstructive lung disease represents the traditional paradigm or the status quo that aligns linearly cigarette smoke and inflammation (6). This hypothesis can be dated to the identification of α1-antitrypsin deficiency (7), which accordingly would allow for the unopposed destructive actions of neutrophil elastase toward the extracellular matrix. The inflammation/protease–antiprotease hypothesis was further supported by the identification of the role of metalloproteases, particularly of metalloprotease-12 (8), and the requirement for neutrophils (9), macrophages (10), and more recently, cytotoxic lymphocytes in the alveolar destruction promoted by cigarette smoke (11). It is always tempting to relate these cellular events to the paradigm of protease–antiprotease imbalance, that is, the pathway of “less resistance” and easier acceptance. However, may a rigid interpretation of the inflammation/protease–antiprotease hypothesis blind one to a more accurate interpretation of the true pathobiological events in lung injury caused by cigarette smoke? Concepts such as the influx and pathogenetic role of inflammatory cells can be explained by an autoimmune attack on lung components damaged by cigarette smoke (5, 12) or superimposed viral infections (13), which cast doubt on the linearity of cigarette smoke as a mere “proinflammatory” agent. Indeed, anti-inflammatory strategies remain to be demonstrated as effective treatments for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Even the traditional concept that elastases are the main and sole target of α1-antitrypsin is being expanded by the evidence that this serpin blocks apoptosis by binding and inhibiting active caspase 3 (14, 15), has direct anti-inflammatory effects (16), and neutralizes the activation of protease activated receptor 1 by thrombin (17).

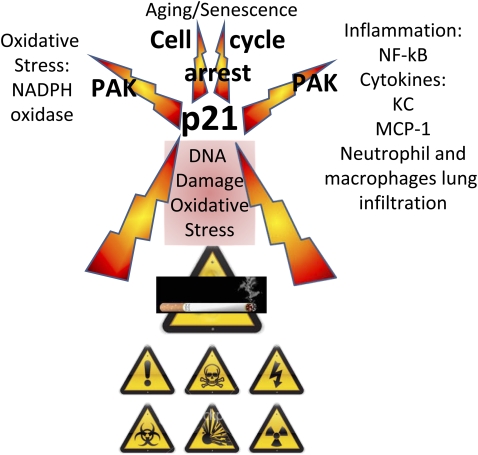

The work by Yao and colleagues reveals that the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP1/WAF1/SDI1 (designated hereafter as p21), which has been linked to cell cycle growth arrest due to stress or “danger” cell responses, may modulate alveolar inflammation and alveolar destruction, and thus enlightens our present understanding of how the lung “senses” injury due to cigarette smoke and integrates these responses with those that activate inflammatory pathways potentially harmful to the lung (Figure 1). Furthermore, the interplay of p21 and cellular processes involving cell senescence and the imbalance of cell proliferation/apoptosis may provide us with a more logical explanation of how p21, acting as a sensor of cellular stress, might have such potent and wide roles in lung responses triggered by cigarette smoke. Molecular switches, ontologically designed for the protection of the host, are now “hijacked” by injurious stresses (such as cigarette smoke), leading to organ damage. This concept, which is shared with the underlying processes that lead to aging, may also apply to several diseases, including COPD (18). It is apparent that a novel paradigm is emerging. This paradigm requires that we consider how cigarette smoke alters the molecular controls of lung cell homeostasis, leading to disruption of alveolar maintenance (19), with the destructive consequences of failure to repair and terminal senescence. These pathobiological processes may provide an alternative or be complementary to the models of unopposed apoptosis and extracellular matrix destruction.

Figure 1.

Summary of role of p21 in alveolar injury caused by cigarette smoke. p21 would act as a “sensor molecule” to cellular stress caused by cigarette smoke, lipopolysaccharide, or fMLP. The pathobiological consequences of p21 involve its roles in senescence and regulation of inflammatory pathways, potentially involving p21-dependent kinase(s).

P21: A REGULATOR OF CELL CYCLE ARREST

Elucidation of the molecular regulation of cell cycle progression has proven to be central to our understanding of the most fundamental processes in living cells. Critical processes of post-replicative cell differentiation, proliferation and repair, neoplastic transformation, cell senescence, and apoptosis, among others, are integrated by molecules directly involved in activating or repressing different stages of cell cycle.

Cell cycle progression to the S phase is regulated by complexes of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) (20). p21 acting as a central downstream target of p53 activation inhibits the cyclin E-CDK2 and cyclin D1-CDK4 complexes, and therefore can induce G1 arrest and block entry into the S phase of the cell cycle (21). Other family members in the Cip/Kip group of Cdk inhibitors include p27Kip1 and p57Kip2, which share significant sequence homology but have different cyclin-CDK targets (22). In the cytoplasm, p21 remains in quaternary complexes with cyclin and Cdks (23). p21 also interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), an accessory protein of DNA polymerase, and thereby inhibits DNA synthesis (24).

The p21 gene is located at 6p21.2. Gene expression of p21 is activated by p53, growth factors including transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), cytokines, retinoids, along with many other factors, including the transcription factors Sp1/Sp3, Smads, Ap2, STAT, BRCA1, E2F-1/E2F-3, and CAAT/enhancer binding proteins a and h (25). c-Myc and c-jun both inhibit p21 expression (25). The biological actions of p21 are determined by its expression levels, affected by transcriptional factor regulation of the p21 promoter, transcript stability, and post-translational controls (25).

DNA damage triggers a “danger response” coordinated by the ataxia telengectasia mutated gene (ATM) and p53. This physiological and temporary response, as seen in γ-irradiation or oxidative stress, aims to lessen the cellular damage as cells go into a waiting period for DNA repair, but can become permanent when cells have dangerously shortened telomeres, that is, DNA-protective TTAGG repeats at the end of chromosomes. This replicative crisis depends on p53 and its downstream target p21. The crisis ultimately leads to a senescent cell (replicative senescence), which is apoptosis resistant and metabolically active but unable to proliferate beyond the G1 stage of the cell cycle. A leading concept is that aging and cell senescence are closely interlinked, potentially by a decrease in the replicative ability of stem cells to efficiently repopulate worn-out organs, leading to organ dysfunction and disease (26). This link has been recently supported by the evidence that prematurely aged mice lacking the soluble protein Klotho have unopposed Wnt-driven maintenance of stem cells, leading to their senescence and inability to maintain homeostasis in stem cell–rich organs (27).

P21 AND CELL SENESCENCE

p21 is both necessary and sufficient to trigger replicative senescence (26). p21 knockout mice are generally healthy without organ system disease (28). Knockout mice do, however, develop spontaneous tumorigenesis, when followed out to an average age of 16 months (29). Mice deficient in the enzyme telomerase, which accounts for telomere repair and elongation of the end of chromosomes, have progressive and premature telomere shortening over generation crosses, particularly in highly replicative and stem cell–rich organs, including testis and the hematopoietic system. p21 is necessary in these mice to induce cell cycle arrest, as knocking out p21 in the telomerase-deficient mice prolongs lifespan with enhanced preservation of stem cells (30). p21 is also sufficient, as cells that are forced to overexpress p21 become arrested in G1 by the increased association of p21 with PCNA, cyclin D1, and Cdk4 (31). p21 is therefore not only required for regulation of the cell cycle in fully mature cells but also affects the outcome of stem cells in circumstances of stresses that may lead to their exhaustion, premature senescence, or aging (32).

The central tenets of the concept of aging and activation of molecular switches involved in “danger” signals have been recently documented in cigarette smoke–induced emphysema. Emphysematous lungs exposed to cigarette smoke express the hypoxia-inducible, oxidative stress modulatory molecule RTP-801 (18). Human emphysematous lungs also have decreased telomere length, enhanced expression of p21, p16Ink4a, p19Arf, and the cytochemical marker of cellular senescence reliant on low pH-activated β-galactosidase activity (33). Furthermore, these results are complemented by evidence that these alterations are systemic since peripheral blood mononuclear cells share the telomere shortening seen in the lung (34) and alveolar macrophages from smokers have increased expression of p21 (35). The links among cell senescence, aging, and predisposition to cigarette smoke–induced emphysema were strengthened by the documentation that prematurely aged mice lacking the anti-aging protein senescence marker protein (SMP)-30 have increased alveolar injury and emphysema caused by cigarette smoke (36). This paradigm may not be restricted to cigarette smoke as recent reports have linked mutations in telomerase and the RNA component of telomerase (TERC) to interstitial lung disease, also shown to be associated with cigarette smoke (37). These data indicate that biological processes involved in aging, particularly oxidative stress, may hold the key to the unrelenting progression of COPD despite smoking cessation. Ceramide, which is increased in lungs of smokers and in mice exposed to cigarette smoke and mediates experimental emphysema (38), has been also shown to cause senescence (39) and promote a feedforward amplification of its pro-oxidative stress and apoptotic actions in vitro (40).

It is tempting to interpret that the pathogenic role of p21 in mice exposed to cigarette smoke may be related to its pro-senescence properties, as suggested by Yao and coworkers (1). The paradigm centered on the role of p21 in senescence reveals facets neither predicted nor investigated by the proponents of the inflammation/protease–antiprotease hypothesis. Senescent cells are more prone to produce cytokines and therefore promote inflammation in vitro (41) and in vivo in late generation mice lacking TERC (26).

Mice lacking p21 had markedly reduced lung inflammatory responses caused not only by acute (i.e., 3 d) cigarette smoke, but also lipopolysaccharide (LPS) inhalation (i.e., 24 h), and N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) administration (i.e., 3 wk). These time frames are too short to postulate that cell senescence alone might have accounted for the injurious roles of p21. An alternative explanation for the observed protection in p21 knockout mice is that p21 drives macrophage maturation and differentiation. p21 knockout mice have decreased macrophage recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques and cytokine expression (42), findings that parallel those of Yao and colleagues (1) in the lung. In elegant studies, Ofulue and Ko showed that macrophages are required for cigarette smoke–induced emphysema in rodents exposed to cigarette smoke (10). Moreover, as p21-deficient macrophages can engulf more efficiently apoptotic cells than wild-type cells, it is possible that the protection seen in p21 knockout mice could be accounted for by the more efficient removal of apoptotic cells triggered by cigarette smoke or LPS inhalation (43).

HOW DOES THE LUNG SENSE THE DETRIMENTAL EFFECTS OF CIGARETTE SMOKE?

Mice lacking p21 show remarkably decreased NF-κB and inflammatory cytokine responses due to cigarette smoke, LPS, or fMLP when compared with wild-type mice (1). Since Yao and coworkers exposed mice to cigarette smoke for just 3 days, it is unclear whether these acute responses would predict or be relevant to long-term outcomes, since cigarette smoke produces mild emphysema in mice after 6 months of exposure to cigarette smoke. Although this potential caveat has not been elucidated thus far, the documentation that acute exposures to cigarette smoke lead to presence of elastin degradation products in bronchoalveolar lavage and alveolar inflammation support the potential relevance of the experimental approach taken by Yao and colleagues (44).

Yao and coworkers expand the scope of their investigation by using inhaled LPS or fMLP. Although LPS is often used to induce acute lung injury, long-term LPS treatment can mimic the COPD phenotype (45), while short-term LPS exposure has shown to induce bronchial epithelial cell apoptosis (46). LPS-induced inflammation is different from cigarette smoke–induced inflammation in that it does not involve metalloprotease-12 activity (47). fMLP, a bacterial peptide that functions as a chemoattractant for phagocytes, induces a full-scale neutrophil response including production of reactive oxygen species, granule enzyme release, and activation of various downstream signaling pathways, including those involving phophoplipase A and D, phosphotidylinositol 3-(PI3) kinase (PI3Kinase), protein kinase C (PKC), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Consistent with its relevance in cigarette smoke–induced lung disease, the fMLP receptor is increased in neutrophils of patients with emphysema and in smokers (48). Both LPS and fMLP might cause alveolar destruction by enhancing neutrophil recruitment to the lung via the action of the collagen-derived peptide N-acetyl proline-glycin-proline (PGP). Degradation of the extracellular matrix generates PGP, which could therefore activate the CXCR2 receptor. This receptor is activated by ELR motif-CXC chemokines (IL-8, GRO-α, -β, and -γ, KC, MIP-1α) (49), which have been linked to recruitment of inflammatory cells to lungs exposed to cigarette smoke (50).

How does p21 regulate an otherwise classical inflammatory pathway? Among all agents of lung stress and injury triggered by cigarette smoke, oxidative stress is a leading and unifying agent of emphysema (51). Not only is cigarette smoke a major source of oxidants, but infiltrating inflammatory cells and alveolar cell apoptosis themselves generate potent free radicals (52). Furthermore, oxidative stress leads to enhanced inflammation (51), apoptosis (52), and potentially senescence via the p53/p21 pathway (41). Cigarette smoke damages DNA (53), which could activate a p53/p21 stress response as suggested by the co-expression of p53 and p21 in alveolar macrophages of smokers (35). The data of Yao and colleagues suggest that p21 enhances oxidative damage, as they demonstrate that p21 knockout mice have decreased levels of superoxide and hydroperoxides in cells retrieved by bronchoalveolar lavage or in lung tissue lysates. These findings are in agreement with data that forced in vitro expression of p21, but not the cell cycle inhibitor p16, triggers enhanced oxidative stress, which conversely up-regulates p21 expression (54).

Although it is unclear how p21 modulates oxidative stress, the authors suggest that p21-dependent kinase (PAK) links p21 with the activation of cytokines and NF-κB–dependent signaling. PAK(s) represent a new mechanism for p21 to influence a diverse array of intracellular processes (55). PAK(s) are serine/threonine kinases that control cytoskeleton dynamics and actin depolymerization. In addition to p21, PAK(s) are activated by GTPases and other signaling molecules.

Inflammation by LPS is mediated by binding to the complex LPS-binding protein (LBP)/CD14/TLR4 and activation of PAK in macrophages and monocytes, leading to release of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-12, KC) (56) and rapid neutrophil infiltration into the lung (57). This pathway is mainly responsible for the LPS-induced increase in vascular permeability (57), suggesting a potential role of p21 in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury or other lung pathologies of increased vascular permeability and inflammation. Neutrophil chemotaxis induced by fMLP is mediated by PAK as well (58), therefore providing a connection between p21 activation by cigarette smoke and lung neutrophil influx. Furthermore, PAK(s) have since been found to influence a broad array of cellular activities including growth-factor and steroid-receptor signaling, energy homeostasis, and transcription and mitotic activity. PAK(s) activate NADPH oxidase by phosphorylating the subunit p47hox of NADPH oxidase. However, the role of NADPH oxidase in the pathogenesis of cigarette smoke–induced lung injury remains unclear. In fact, a recent report suggests that NADPH oxidase can be protective, as knockout mice have increased alveolar destruction with activation of macrophage metalloprotease (59). Decreased activation of antioxidants by NRF-2, a master transcription factor responsible for the up-regulation of several critical antioxidant gene expression (60), or a potential role of p21 in alveolar cell apoptosis are alternatives not pursued by Yao and coworkers to account for the susceptibility of p21 wild-type mice to cigarette smoke.

CONCLUSIONS

The novelty of the findings of Yao and colleagues lends itself to potential translational implications of manipulations of p21 levels and/or activity in cigarette smoke–induced lung injury, particularly of emphysema. As aforementioned, there are no therapies for the manifestations of chronic bronchitis and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Their work is clearly relevant, since there is compelling evidence that smokers have increased expression of p21 and that cigarette smoke induces p21 expression in vitro and in experimental animals (35). Evidence that inhibition of p21 in wild-type mice exposed to cigarette smoke prevents or attenuates lung injury by cigarette smoke would have strengthened significantly the impact of the study by Yao and coworkers. Notwithstanding the advantages afforded by the availability of knockout mice, there is the risk that their attenuated responses to cigarette smoke (and LPS or fMLP) might have been shaped by compensatory mechanisms developed throughout their lifetime. Furthermore, a central question that remains unanswered is which lung cells mediate the p21 effects. Given that lung parenchymal and inflammatory cells have distinct but synergistic interactions throughout lung injury by cigarette smoke, these data are critical for the design of cell-specific treatment strategies.

As in most centrally placed signaling molecules, there is a “biological price” to pay if these molecules are blocked or overexpressed. p21 plays a central role in stem cell maintenance, particularly during situations of stress. Too much or too little p21 leads to a decreased stem cell pool or stem cell exhaustion, respectively (26). The role of p21 remains ambiguous as some reports have described either worse or improved phenotypes in p21 knockout mice. In line with this potential discrepancy, we have observed that p21 knockout newborn mice showed significant lung damage to hyperoxia, including alveolar enlargement and evidence of alveolar cell apoptosis, when compared with wild-type pups (61).

The work by Yao and colleagues, the human data regarding expression markers of cell senescence both in the lung and systemically, and the observation of emphysema in accelerated senescence models offer a novel perspective on the pathogenesis and progression of alveolar destruction due to cigarette smoke. Modulation of central pathobiological processes, such as oxidative stress, which intersect through relevant lung injury processes, including inflammation, apoptosis, and aging, remain an ideal target for therapies, with a potential application to those individuals predisposed to develop the disease as well as patients with advanced disease. However, as we learn of upstream “triggering” mechanisms involved in alveolar injury by cigarette smoke, such as p21, stage- and disease-specific therapies can be designed, particularly addressing earlier stages of the disease before overwhelming destruction, allied to progressive refinement of genetic markers of disease (62).

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health HL66554 and Alpha 1 Foundation research grants (to R.M.T.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0117TR on May 5, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: R.M.T. received an unrestricted postdoctoral support grant from Quark Biotech for studies involving RTP801 in cigarette smoke–induced emphysema; $2,500 for speaker fees in a international conference sponsored by Astra Zeneca; and $1,500 from the Rush Medical Center's CME speakers training workshop titled “Simply Speaking PAH: An Expert Educators CME Lecture Series.” None of the other authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Yao H, Yang SR, Edirisinghe I, Rajendrasozhan S, Caito S, Adenuga D, O'Reilly MA, Rahman I. Disruption of p21 attenuates lung inflammation induced by cigarette smoke, LPS and fMLP in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions, 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1970.

- 3.Pajares, F. 2008. Outline and study guide for the “Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn”. http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/kuhn.html.

- 4.Tuder RM. Aging and cigarette smoke: fueling the fire. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:490–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SH, Goswami S, Grudo A, Song LZ, Bandi V, Goodnight-White S, Green L, Hacken-Bitar J, Huh J, Bakaeen F, et al. Antielastin autoimmunity in tobacco smoking-induced emphysema. Nat Med 2007;13:567–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro SD. The pathogenesis of emphysema: the elastase:antielastase hypothesis 30 years later. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 1995;107:346–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eriksson S. Studies in alpha-1-atitrypsin. Acta Med Scand 1965;177:1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hautamaki RD, Kobayashi DK, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Requirement for macrophage elastase for cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. Science 1997;277:2002–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro SD, Goldstein NM, Houghton AM, Kobayashi DK, Kelley D, Belaaouaj A. Neutrophil elastase contributes to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. Am J Pathol 2003;163:2329–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ofulue AF, Ko M. Effects of depletion of neutrophils or macrophages on development of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Am J Physiol 1999;277:L97–L105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maeno T, Houghton AM, Quintero PA, Grumelli S, Owen CA, Shapiro SD. CD8+ T cells are required for inflammation and destruction in cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Immunol 2007;178:8090–8096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agusti A, MacNee W, Donaldson K, Cosio M. Hypothesis: does COPD have an autoimmune component? Thorax 2003;58:832–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Retamales I, Elliott WM, Meshi B, Coxson HO, Pare PD, Sciurba FC, Rogers RM, Hayashi S, Hogg JC. Amplification of inflammation in emphysema and its association with latent adenoviral infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrache I, Fijalkowska I, Zhen L, Medler TR, Brown E, Cruz P, Choe KH, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Scerbavicius R, Shapiro L, et al. A novel antiapoptotic role for alpha1-antitrypsin in the prevention of pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1222–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrache I, Fijalkowska I, Medler TR, Skirball J, Cruz P, Zhen L, Petrache HI, Flotte T, Tuder RM. Alpha-1 antitrypsin inhibits caspase-3 activity, preventing lung endothelial cell apoptosis. Am J Pathol 2006;169:1155–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janciauskiene SM, Nita IM, Stevens T. Alpha1-antitrypsin: old dog, new tricks. Alpha1-antitrypsin exerts in vitro anti-inflammatory activity in human monocytes by elevating cAMP. J Biol Chem 2007;282:8573–8582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Churg A, Wang X, Wang RD, Meixner SC, Pryzdial ELG, Wright JL. α1-Antitrypsin suppresses TNF-α and MMP-12 production by cigarette smoke-stimulated macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Petrache I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of alveolar destruction in emphysema: an evolutionary perspective. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Voelkel NF. Molecular pathogenesis of emphysema. J Clin Invest 2008;118:394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekholm SV, Reed SI. Regulation of G(1) cyclin-dependent kinases in the mammalian cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2000;12:676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnier JB, Nishi K, Goodrich DW, Bradbury EM. G1 arrest and down-regulation of cyclin E/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by the protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine are dependent on the retinoblastoma protein in the bladder carcinoma cell line 5637. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:5941–5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev 1995;9:1149–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cazzalini O, Perucca P, Valsecchi F, Stivala LA, Bianchi L, Vannini V, Prosperi E. Intracellular localization of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CDKN1A-GFP fusion protein during cell cycle arrest. Histochem Cell Biol 2004;121:377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boulaire J, Fotedar A, Fotedar R. The functions of the cdk-cyclin kinase inhibitor p21WAF1. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2000;48:190–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gartel AL, Radhakrishnan SK. Lost in transcription: p21 repression, mechanisms, and consequences. Cancer Res 2005;65:3980–3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ju Z, Choudhury AR, Rudolph KL. A dual role of p21 in stem cell aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1100:333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, Malide D, Rovira II, Schimel D, Kuo CJ, et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science 2007;317:803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell 1995;82:675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Caballero J, Flores JM, Garcia-Palencia P, Serrano M. Tumor susceptibility of p21(Waf1/Cip1)-deficient mice. Cancer Res 2001;61:6234–6238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choudhury AR, Ju Z, Djojosubroto MW, Schienke A, Lechel A, Schaetzlein S, Jiang H, Stepczynska A, Wang C, Buer J,et al. Cdkn1a deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan of mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating cancer formation. Nat Genet 2007;39:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekiguchi T, Hunter T. Induction of growth arrest and cell death by overexpression of the cyclin-Cdk inhibitor p21 in hamster BHK21 cells. Oncogene 1998;16:369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ju Z, Rudolph L. Telomere dysfunction and stem cell ageing. Biochimie 2008;90:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence in pulmonary emphysema patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:886–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morla M, Busquets X, Pons J, Sauleda J, MacNee W, Agusti AG. Telomere shortening in smokers with and without COPD. Eur Respir J 2006;27:525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomita K, Caramori G, Lim S, Ito K, Hanazawa T, Oates T, Chiselita I, Jazrawi E, Chung KF, Barnes PJ, et al. Increased p21CIP1/WAF1 and B cell lymphoma leukemia-xL expression and reduced apoptosis in alveolar macrophages from smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato T, Seyama K, Sato Y, Mori H, Souma S, Akiyoshi T, Kodama Y, Mori T, Goto S, Takahashi K, et al. Senescence marker protein-30 protects mice lungs from oxidative stress, aging, and smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, Alder JK, Ingersoll RG, Markin C, Lawson WE, Xie M, Vulto I, Phillips JA III, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1317–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrache I, Natarajan V, Zhen L, Medler TR, Richter AT, Cho C, Hubbard WC, Berdyshev EV, Tuder RM. Ceramide upregulation causes pulmonary cell apoptosis and emphysema-like disease in mice. Nat Med 2005;11:491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venable ME, Obeid LM. Phospholipase D in cellular senescence. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999;1439:291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medler TR, Petrusca DN, Lee PJ, Hubbard WC, Berdyshev EV, Skirball J, Kamocki K, Schuchman E, Tuder RM, Petrache I. Apoptotic sphingolipid signaling by ceramides in lung endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;38:639–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell 2005;120:513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merched AJ, Chan L. Absence of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 modulates macrophage differentiation and inflammatory response and protects against atherosclerosis. Circulation 2004;110:3830–3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henson PM, Cosgrove GP, Vandivier RW. State of the Art. apoptosis and cell homeostasis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:512–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Churg A, Wang RD, Xie C, Wright JL. Alpha-1-antitrypsin ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in the mouse. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vernooy JH, Dentener MA, van Suylen RJ, Buurman WA, Wouters EF. Long-term intratracheal lipopolysaccharide exposure in mice results in chronic lung inflammation and persistent pathology. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vernooy JHJ, Dentener MA, van Suylen RJ, Buurman WA, Wouters EFM. Intratracheal instillation of lipopolysaccharide in mice induces apoptosis in bronchial epithelial cells. no role for tumor necrosis factor-α and infiltrating neutrophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001;24:569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leclerc O, Lagente V, Planquois JM, Berthelier C, Artola M, Eichholtz T, Bertrand CP, Schmidlin F. Involvement of MMP-12 and phosphodiesterase type 4 in cigarette smoke-induced inflammation in mice. Eur Respir J 2006;27:1102–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stockley RA, Grant RA, Llewellyn-Jones CG, Hill SL, Burnett D. Neutrophil formyl-peptide receptors. Relationship to peptide-induced responses and emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weathington NM, van Houwelingen AH, Noerager BD, Jackson PL, Kraneveld AD, Galin FS, Folkerts G, Nijkamp FP, Blalock JE. A novel peptide CXCR ligand derived from extracellular matrix degradation during airway inflammation. Nat Med 2006;12:317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshida T, Tuder RM. Pathobiology of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol Rev 2007;87:1047–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacNee W. Oxidants/antioxidants and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: pathogenesis to therapy. Novartis Found Symp 2001;234:169–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tuder RM, Petrache I, Elias JA, Voelkel NF, Henson PM. Apoptosis and emphysema: the missing link. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;28:551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X, Conner H, Kobayashi T, Kim H, Wen F, Abe S, Fang Q, Wang X, Hashimoto M, Bitterman P, et al. Cigarette smoke extract induces DNA damage but not apoptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;33:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.. Macip S, Igarashi M, Fang L, Chen A, Pan ZQ, Lee SW, Aaronson SA. Inhibition of p21-mediated ROS accumulation can rescue p21-induced senescence. EMBO J 2002;21:2180–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar R, Gururaj AE, Barnes CJ. p21-activated kinases in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Togbe D, Schnyder-Candrian S, Schnyder B, Doz E, Noulin N, Janot L, Secher T, Gasse P, Lima C, Coelho FR, et al. Toll-like receptor and tumour necrosis factor dependent endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Int J Exp Pathol 2007;88:387–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stockton R, Reutershan J, Scott D, Sanders J, Ley K, Schwartz MA. Induction of vascular permeability: beta PIX and GIT1 scaffold the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by PAK. Mol Biol Cell 2007;18:2346–2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang R, Lian JP, Robinson D, Badwey JA. Neutrophils stimulated with a variety of chemoattractants exhibit rapid activation of p21-activated kinases (Paks): separate signals are required for activation and inactivation of paks. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18:7130–7138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kassim SY, Fu X, Liles WC, Shapiro SD, Parks WC, Heinecke JW. NADPH oxidase restrains the matrix metalloproteinase activity of macrophages. J Biol Chem 2005;280:30201–30205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 2004;114:1248–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGrath-Morrow SA, Cho C, Soutiere S, Mitzner W, Tuder R. The effect of neonatal hyperoxia on the lung of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 deficient mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tuder RM, McGrath S, Neptune E. The pathobiological mechanisms of emphysema models: what do they have in common? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2003;16:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]