Abstract

This article reports on considerable variety and diversity among discourses on their own jobs of boundary workers of several major Dutch institutes for science-based policy advice. Except for enlightenment, all types of boundary arrangements/work in the Wittrock-typology (Social knowledge and public policy: eight models of interaction. In: Wagner P (ed) Social sciences and modern states: national experiences and theoretical crossroads. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991) do occur. ‘Divergers’ experience a gap between science and politics/policymaking; and it is their self-evident task to act as a bridge. They spread over four discourses: ‘rational facilitators’, ‘knowledge brokers’, ‘megapolicy strategists’, and ‘policy analysts’. Others aspire to ‘convergence’; they believe science and politics ought to be natural allies in preparing collective decisions. But ‘policy advisors’ excepted, ‘postnormalists’ and ‘deliberative proceduralists’ find this very hard to achieve.

Abstract

Der niederländische Diskurs über die interdisziplinäre Perspektive von Beschäftigten in der wissenschaftlichen Politikberatung zeigt eine erhebliche Variationsbreite auf, die im Folgenden erörtert werden soll. Ausgehend von der „Wittrock-Typologie” (1991) sind—mit Ausnahme der erkenntnisbildenden Typen—alle Querschnittsansätze vertreten. Diejenigen, die eine grundsätzliche Divergenz zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik postulieren, sehen sich als Bindeglied zwischen diesen Polen. In entsprechenden Diskursen nehmen diese entweder die Position von „rationalen Unterstützern”, „Informationsvermittlern”, „Megapolitik-Strategen” oder „Politik-Analysten” ein. Andere wiederum postulieren eine Konvergenz zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik, die beide als natürliche Verbündete im Interesse kollektiver Entscheidungen sehen. Diese Konvergenz scheint aber aus Sicht der „postnormalen” Politikberatung bzw. der „deliberativen Prozeduralisten” kaum jemals erreichbar zu sein.

Résumé

Cet article témoigne de la variété et diversité considérables de discours concernant leurs propres métiers, par les spécialistes du travail frontière de plusieurs instituts hollandais importants, spécialisés dans le conseil des règles scientifiques. Tous les types de l’agencement/travail frontière que l’on retrouve dans la typologie de Wittrock (1991) se produisent, sauf l’éclaircissement. Les “divergents” constatent un décalage entre les sciences et la législation et évidement, leur tâche est de combler cet écart. Ils développent quatre voies: “facilitateurs rationnels”, “courtiers en connaissances”, “méga stratège politique” et “analyste politique”. Par ailleurs, ceux qui prétendent à la “convergence”, croient que les sciences et la politique sont des alliés naturels et doivent prendre des décisions en commun. Cependant, à l’exception des “conseillers politiques”, les “post-normalistes” et les “procéduriers délibérateurs” trouvent qu’il est très difficile d’y parvenir.

Research problem and theoretical framework

Much has been written about the role(s) of scientific expertise in the political arena and public policy. Leaving behind the user-focused, one-directional knowledge utilization model in policy studies, and the co-producer-oriented seamless web model of science/politics interaction in STS studies, contemporary conceptions focus on boundary arrangements and work. (Halffman 2003:63–66) suggests a definition of boundary work as a practice in contrast with other practices, which protects it from unwanted participants and interference, while attempting to prescribe proper ways of behavior for participants and nonparticipants (demarcation); at the same time, boundary work defines proper ways for interaction between these practices and makes such interaction conceivable and possible (coordination). Boundary work can be analyzed on three levels: discourses, practices, and organizational boundaries or arrangements. This research addresses discourse. Discourses are systematized versions of how actors conceive of the division of labor between science and politics. Discourses can be mobilized in boundary work. They are discursive repertoires (Bal 1999; Hoppe and Huijs 2003) used to settle boundary disputes.

What repertoires do exist? How many are there? Are they well articulated, or fuzzy? Wittrock (1991) and, standing on his shoulders, Hoppe (2005) has shown that, using the boundary arrangement/work perspective, the historical line of research and theorizing can be collapsed in a typology.

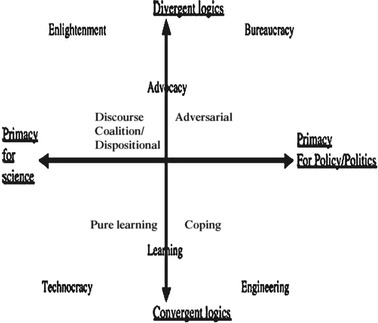

The typology (see Fig. 1) is constructed along the axes of ‘primacy’ and ‘societal logic’. The first axis, borrowed from Jürgen Habermas’ work, concerns relative primacy in terms of control and authority. Habermas conceives of this dimension as a three-valued continuum. On one end, the relationship science-politics is called technocratic when science dominates or displaces politics. On the opposite side, the relationship is decisionist when representatives of political bodies have the first and the last say. In the middle is a third, pragmatist model of politics and science as countervailing powers in equilibrium; their boundary traffic may be conceived of as dialogue or debate.

Fig. 1.

Types of boundary arrangements (taken from Hoppe 2005, based on Wittrock 1991)

Swedish sociologist Björn Wittrock (1991:338) drew attention to a second dimension, which he called the presupposed convergence or divergence between the operational codes of science and politics. Insisting on divergent operational codes, science and politics are considered incompatible ways of life, whose relational logic is Either/Or. Blurry boundaries between science and politics look much more tolerable from a relational logic of Both/And. In this view, no matter how different, science and politics serve the same societal functions: the creation of consensus and the fight against chaos as preconditions for social coherence, cooperation, and collective action (Diesing 1991:80; Schmutzer 1994:366; Ezrahi 1990; Fuller 2001).

(Hoppe 2002a: 37–62, and Hoppe 2002b) has shown the relevance of these models for the issues, controversies sometimes, in debates on the governance of expertise: either ‘streamlining’ and ‘economizing’ or, alternatively, ‘democratizing expertise’. Such issues were listed as (Woodhouse and Nieusma 1997, 2001) following: dealing with normative issues; with different, potentially conflicting, types of knowledge (different disciplines, scientific versus lay or experiential knowledge); with uncertainty; with modes of institutionalizing boundaries; with possibilities for policy-oriented learning; and with the creation, maintenance and erosion of mutual trust between experts and politicians or policymaking bureaucrats. For each of these issues, the models can be used to generate hypothetical, often conflicting answers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of (dis)similarities between models of boundary arrangements on selected facets of the governance of expertise

| Dealing with | Enlightenment | Technocracy | Bureaucracy | Engineering | Advocacy | Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | Political responsibility | Scientific operationalizations of the ‘good’ | Political responsibility | Political responsibility | Pluralist interest articulation | Convergent ‘rational’ ideologies; cyclical priorities |

| Knowledge conflicts | Conflict avoidance | Conflict avoidance; spontaneous hegemony | Rule-bound demarcation of expertise and tasks | Ad libitum; actor-bound, local | Equal status; usable knowledge | Positive/negative heuristic; mutual adjustment |

| Uncertainty | Political responsibility | Temporary problem; disregard or hedge | Rule-governed control from systems perspective | Fallibilist; actors’ perspective | Negotiation; robustness | Designed and/or spontaneous learning |

| Institutional nexus | Accidental, ad hoc | Science leads; politics legitimises | Politics leads; loyal instrumental research | Project-focused; principal—agent | Flexible play with distance and overlap | Professional platforms and/or social debate |

| Policy-oriented learning | Accidental | Experimental logic | Instrumental learning | Not structurally guaranteed | Spontaneous learning | Designed and/or spontaneous learning |

| Trust/distrust | Institutional distrust | Institutional distrust | Ambivalent | Conditional trust | Unsteady balance; trust-work | Institutional trust |

The problem addressed in this article is that the typology and its implications for the governance of expertise are not grounded in conceptions of actors involved (experts, policy makers). Instead, the typology is a digest and systematization of the thinking of philosophers of science and research and theorizing by social scientists. They have reflected upon the relation between science and politics, perhaps as found in the conceptions of actors, or in observations on their actual division of labor. But the implicit, as yet unsubstantiated claim in the typology is that it catches the conceptions that live among actors involved. Full-fledged testing of this claim is not the purpose of this article. Rather, it is a first step in empirically exploring to what extent boundary workers’ thoughts and discourses on their own typical activities do or do not show similarities to the academic typology.

This appears a worthwhile endeavor not only in view of the typology’s empirical underpinning. It is surprising how little research has actually been done on the role of scientific expertise in politics and policymaking in which the differences between views of the participants themselves—modellers, experts, science advisors, policy bureaucrats, politicians—have been empirically probed seriously (e.g., Bemelmans-Videc 1984; Meltsner 1990; Van Dalen and Klamer 1996; Bal et al 2002; den Butter and Morgan 2000). Most work on this subject implicitly or explicitly aims at composite units, and higher, aggregate levels of analysis, with the theorist or researcher necessarily imposing the aggregator’s view: styles of using scientific expertise in scientific advisory committees or agencies (Jasanoff 1990; Smith 1992; Powell 1999), or policy sectors (Bal and Halffman 1998; Bal 1999; Halffman 2003) or even the political regime as a whole (e.g., Renn 1995).

A Q-method research design

Drawing a cartography directly based on boundary workers’ conceptions, or comparing academic and practitioners’ maps, implies a systematic analysis of their discourses-in-use. Using a Q-method research design enables the researcher to take a meaningful first step in this direction. Q-method (McKeown and Thomas 1988; Brown 1980) was developed to systematically inquire into human operant subjectivity, or the ways people create and use categories, dimensions, properties, or styles of discourse in going about their business in daily life worlds.

The Q-sample and interview

Respondents were asked to sort 42 statements on aspects and properties of boundary arrangements and practices of boundary work, from an insider’s perspective. They were presented cards with statements or propositions. Respondents had to sort these into a number of categories, representing the degree to which they reflect or deviate from their own standards, opinions, views or experiences. During the interview, the interviewer prompts respondents to account for their way of sorting statements. Respondents may shift cards/statements, as they sort the statements relative to one another. A Q-method interview is finished when the respondent is satisfied with the distribution of statements. The completed distribution is called a Q-sort. The validity of a Q-method design is crucially influenced by its Q-sample, the set of statements to be sorted (see Appendices 1 and 2). The Q-sample should at least approximate the variety in the ‘concourse’; statements should represent all important aspects or properties or dimensions of a particular discursive field. In this research project, the Q-sample was derived from the typology of boundary arrangements/practices and its implications for the governance of expertise presented earlier. For reasons of feasibility, the number of Q-statements was restricted to 42. The validity of the Q-sample was checked by asking each respondent, at the end of the interview, about omissions and biases.

The P-sample or selection of respondents

The purpose of the P-sample is not representativeness,1 but to map diversity and variety in beliefs and opinions. To capture as much varied experience as possible, I chose to talk mainly to people in leadership positions in boundary institutes and corresponding policy organizations. A sample of N = 22 is large enough for variety mapping purposes (see Appendices 3 and 4). In recruiting respondents, I used two types of information. First, the research reported here is part of a larger research project involving multiple case studies.2 Case researchers have listed potential respondents on the basis of their in-depth knowledge of actors involved. Second, in May, 2006, three typical boundary organizations, the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (CPB), the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (MNP), and RAND Europe, jointly organized a conference on how to deal with and communicate uncertainty in policy advice (CPB/MNP/Rand Europe 2008). The list of participants also was used as a guide to boundary workers, especially from the policy side. I recruited an equal number of respondents engaged in boundary work from the scientific (n = 9) and the policy side (n = 7). Of course, there are those whose careers alternate, or combine both from the beginning (n = 6).

Factor analysis

In Q-factor analysis the factors represent groups of persons with highly similar (statistically correlated) Q-sorts. The outcome of a Q-factor analysis is a number of clusters of persons that obviously share a perspective or vision. It is possible to calculate the (weighed) average score for each cluster for each single statement, and in so doing to calculate the ‘ideal’ Q-sort for this particular cluster of persons. It is the interpretation of ‘normalized factor scores’, the scores of the (statistically) ‘ideal’ member of a group of persons on a particular set of statements, which enables the researcher to unearth the typical discourses of different clusters of respondents.

Interpretation

The quantitative interpretation of data was based on principal component analysis of the unrotated factor matrix; varimax rotation with 7 factors, on 22 respondents; correlation analysis of factor arrays (see Appendix 3); flagging of salient or defining persons per factor (see Appendix 3), defining statements per factor (see Appendices 1 and 3), and most-different statements between factor arrays; all on standard statistical grounds.3 The explained variation for all seven factors was 73%. Taking a loading of 0.4 as cut-off point, all respondents load on at least one factor, and all factors are sufficiently ‘populated’ to accept them as genuine. Only 5 out of 22 respondents load on more than one factor (see Appendix 3). Correlations between factor scores indicate the autonomous character of most factors, although correlations between factors 1 and 3, and between 3–4 and 6 are considerable (see Appendix 2). Qualitative interpretation was based on analysis of all statements in the context of verbatim transcriptions of interviews. Interpretation rests on inspection of most positive (+4, +3) and most negative statements (−4, −3); most significant statements per factor array; and concluding and summary key statements of their views on boundary arrangements/practices by all respondents.

Interpretation of findings

First, I describe a working consensus, more or less shared by all boundary workers in the Netherlands. Subsequently, I typify seven discourses of boundary work :

Factor 1: rational facilitators of accommodation;

Factor 2: knowledge brokers;

Factor 3: megapolicy strategists;

Factor 4: policy analysts.

Factor 5: policy advisors;

Factor 6: post-normal scientists/analysts; and

Factor 7: deliberative proceduralists.

A working consensus

Out of 42 statements, three (##26, 31, 34) show a strong consensus; another five (##32, 6, 22, 10, 28) reflect considerable, but not complete consensus.

Two consensus statements show boundary workers’ identification with and pride in their own jobs. The first statement is:

#10 Politics and/or policy learn from science only by chance, if at all.

Not surprisingly, boundary workers unisono, but in varying gradations (−1 till −4), reject this statement. After all, confirmation would be equal to admitting failure or futility of their professional work:

“What does ‘chance’ mean in this case? No, I disagree. I think there is a lot of construction and manipulation here.”

The second strong consensus statement on the nature of boundary work is a rejection of

#28 Scientific experts and advisers are lawyers; their business is advocacy for political positions.

Except for departmental policy advisors and procedural deliberationists, who may have interpreted the statement as descriptive of much current practice (−1, and 0), all other respondents strongly reject (−3, −4) this statement. They see it as a devaluation and loss of credibility of science-based advice and boundary work. Sometimes it is argued that this role conception is detrimental to the political game in a democracy:

“If experts become advocates their credibility is in shambles.”

But this does not imply a denial of an ‘advocacy-for-science’ role in the policy process:

“(It is important) to advocate insights and beliefs grounded in science…in order to put them on the political agenda… But I would object to taking political views as a point of departure…”

A second set of consensus statements reflects Dutch boundary workers’ socialization in the political arenas and policy networks typical for the Dutch consensus-type of democratic and neo-corporatist political regime (Halffman and Hoppe 2005). The first statement extols the virtues of consensus democracy in clarifying normative issues:

#31 Normative issues are difficult to grasp; people discover values only in dialogue with or comparison to other people.

This statement is believed to be true by all seven types:

“Yes, I agree. The meaning of values is clarified only in the articulation of contrary values or alternative options. Only then you find out what is truly at stake. Your confusion is disclosed: ‘I adhere to this value, but don’t ask for arguments, for I do not have them.’”

Another consensus statement is about how politics deals with scientific uncertainty:

#34 Uncertain knowledge defines the free decision space for political action.

Except for departmental knowledge brokers (0), all others are convinced of this statement’s plausibility:

“This sounds OK. Uncertainty exists, and politicians have to deal with it. …The issue is precisely how to decide under uncertainty. … Yes, this implies spaces for negotiation. You may distribute uncertainty, by saying…if you deal with this risk, I will be responsible for that one.”

“Yes, uncertainty is an undeniable fact. But is it a desirable fact? Absolutely not! …For increasing complexity inherently opens up the space for…yes…messing around. What happens in clean air policy now…If policymakers open the hood and start fiddling the plugs…things get out of hand.!”

This latter quote indicates that subscribing to statement #34 may reflect the counterpart-belief that freedom of political action, or its scope, will be reduced where scientific certainty reigns.4 This would align with the dominant way politicians and boundary workers look at the function of scientific findings for politics: constraining its scope of action; thereby reducing political transaction costs, and boosting the legitimacy of decisions/actions based on scientific data/knowledge (Halffman and Hoppe 2005).

Another consensus statement is about the standard interpretation by political scientists of the role of science as depoliticization mechanism:

#32 Science and expertise have the political function of a ‘refrigerator’ for issues that, for some reason or another, are ‘too hot to handle’.

All respondents say they acknowledge the phenomenon as happening relatively frequently; but some deem it more important than others; sometimes even positively, in the sense that it allows policy ideas to mature:

“Sometimes it works quite well: getting used to a novel situation. Science is not just a ‘refrigerator’, but sometimes a ‘breeding ground’.”

In a consensus democracy, dealing with knowledge by citizens, stakeholders, and practitioners is of considerable interest to boundary workers:

#6 When the chips are down, lay and practitioners’ knowledge have less value than scientific knowledge; therefore, they deserve no standing at the policy table.

All respondents reject this statement (−1, −4). Some reject it rather strongly and in principle:

“It is not less valuable knowledge; it is ‘different’ knowledge. …As a good scientist, giving policy advice means trying to give experiential expertise and lay knowledge their proper places.”

Others reject it, but with some misgivings:

“It says that lay knowledge deserves no standing at the policy table…If the statement would have been a ‘subordinate role’, I would have fully agreed.”

All these consensus statements imply that Dutch boundary workers normatively incline towards pragmatist arrangements. They say they feel obliged to take into account both what lay persons and practitioners say (#6), and insights and knowledge from science (#10).

Finally, two consensus statements deal with the neo-liberal trend in science-based policy advice, namely its commodification and the emergence of commercial policy consultancy (Halffman and Hoppe 2005). The consensus reflects an ambiguous, but not disapproving attitude. Departmental knowledge brokers and policy advisors, confirm the statement:

#22 Scientific knowledge should be seen as information that, when and where available, can be purchased at a reasonable price.

But they are also aware of the potential dangers. Says one knowledge broker:

“As policy adviser you should minimally be able to assess what knowledge is required for policy preparation. You should worry in time. Do not think: some nice cut-and-paste job will do the trick. You need a system; you should know enough to know what you don’t know; have a feel for knowledge gaps.”

But respondents loading on other factors more or less (−1, −2) reject the idea that knowledge is just another commodity. Usually they stress both that knowledge ought to be a free, public good, and that knowledge applied to specific (policy) problems will cost extra due to quality considerations. Yet, boundary workers are not opposed to outsourcing in general, especially for short-term, instrumental analysis and advice jobs:

# 26 In outsourcing research it is difficult to create a relationship of mutual trust.

Only policy analysts appear to be indifferent here (0); all others reject the statement (−1, −2):

“I feel that the model of having institutionalized relationships with one knowledge institute that has its own scientific autonomy…is a good system. But … you just have to publicly outsource part of your research. If only to test your institutionalized partner’s performance. But also just because you can’t have a fixed partner for everything.”

Summarizing, Dutch boundary workers have nothing against occasionally outsourcing short-term, instrumental research for policy.

Factor 1. Rational facilitators of accommodation: “In trust we may transgress.”

With four respondents Factor 1 is the second largest one. They are a motley company of boundary workers in different functions and different institutes—a prominent member of an advisory council, two staff of renowned research and advisory bodies, one department-based research coordinator. There are no distinguishing statements for this factor alone. Factor 1 shows positive correlations with factor 3 (megapolicy strategists; 0.4980) and factor 6 (postnormal analysts; 0.4363).

Rational facilitators appear indifferent to divergent beliefs, and mildly critical of convergent beliefs about science and politics (#4, 0; #5, −1). All respondents hesitate to express strong views on the issue, but for very different reasons: “It is almost a philosophical question”, “Boundary work is a kind of grey zone in between the extremes of a continuum”. Yet, if one probes deeper, it is clear that the rejection of a convergent attitude (#5) prevails:

“For politics, creating conditions for cooperation is a mission; for science, it is at best a by-product.”

In the concluding statement, one of the respondents typically emphasized his firm belief in the Dutch political style of flexibility and compromise. In this tradition, boundary work is facilitating the transgression or “boundary-crossing” between thinking (= science) and action (= politics). This facilitation is a deliberately organized activity; it cannot be left to spontaneity or chance (−3, #10).

Looking at the strongest positive statements (+4: #40, #33), rational facilitators, from a political point of view, ascribe only a moderate role to scientific expertise in the policy process. They stress that different types of knowledge will be more or less useful to politics, due to whether or not they coincide with political value systems. Thus, on the one hand, scientific expertise, as the ‘force of good arguments’, should not be disparaged by policymakers (−3, #38); but on the other hand, lay and practitioners’ knowledge definitely also deserve standing at the policy table (−3, #6).

On the basis of other highly positive statements (+3, #8, #9) it may be inferred that rational facilitators deem it necessary to have rather close ties to policymakers. Although politics has to decide how to deal with uncertainty in the short run (+3, #8), rational facilitators hope that, in the long run, science will make political ideologies more rational and less important (+3, #39). As one respondent put it: especially in long-term policy issues, science advisors ought to clearly communicate uncertainties. Policymakers may be unwilling to confront scientific uncertainty. But in an atmosphere of close contacts and mutual trust reasonably good communication is possible.

Condensing the analysis, rational facilitators of political accommodation are believers in the Dutch consensus-type democratic practices of flexibility and compromise; they feed the accommodation process with sound arguments, derived from both sound science and knowledge rooted in stakeholders’ knowledge of ‘best practices’; they perceive themselves as facilitators of orderly transgressions between politics and science; this is possible only in an atmosphere of mutual trust.

Factor 2. Knowledge broker: “In spite of the constraints, let’s make the best of it.”

This factor is made up of two civil servants in different departments. One is more concerned with coordinating external research; the other with disseminating acquired knowledge among policy units. Each combines knowledge brokerage and management with advisory roles. Factor 2 shows two defining statements that set it apart from all other factors. Low correlations with other factors indicate that Factor 2 is highly independent.

In contrast to the facilitators’ weak belief in divergence, knowledge brokers or managers show weak belief in both convergence (#5, +1) and divergence (#4, +1). They manage to hold these contrary beliefs by constructing the relationship between pre-cooked ideological beliefs in politics and the radical suspension and empirical testing of belief in science, as one of opportunistic tinkering. The differences are bridged by the opportunistic behavior of knowledge ‘peddlers’ and policy entrepreneurs. This idea goes with a rather pessimistic view of both the politics of science and bureaucratic politics.

Both defining statements deal with issues of science and learning: knowledge brokers forcefully reject that experiments are helpful (in social policy problems) (#15), and affirm that learning is limited to lower-order instrumental learning (#37):

#37 In public policy, learning is limited to instrumental, financial and organizational matters (+4).

#15 If you desire policy-oriented learning, you should design experiments (−4).

This is because in politics knowledge inevitably has “fluctuating index values in the political ‘stock exchange’” (#40, +4). Yet, in the longer run, scientific expertise has a real contribution in rationalizing political ideologies (#39, +3).

Comparing facilitators to knowledge brokers on the two defining statements, it is clear that the brokers are more skeptical; partly about science, but even more about the ‘absorption capacity’ and other intellectual impairments in politics and bureaucracy. Says one respondent as concluding statement:

“The condition (for an improved relationship, rh) is that government (as principal) should ask better questions, and know what it really wants, and that science can really answer the question. This is a matter of reciprocity in which, frequently, politics has to move more toward science than the other way round and refrain from asking verbose and diffuse questions that mask or avoid (interdepartmental) conflicts; scientists, on the other hand, should have the courage to push for more precise questions and show more empathy. …”

Summarizing the above, knowledge brokers believe that, in spite of (well-known) cognitive impairments of politics and bureaucracy, and in spite of the inevitable gap between politics and science, under favorable conditions, knowledge brokers in government may exploit opportunities for instrumental learning. Although many colleagues would accuse knowledge brokers of resignation in the coping character of politics and policy, they would counter that, after all, they make the best of it.

Factor 3. Megapolicy strategists: “Let’s challenge government to think!”

This factor represents a fairly homogeneous cluster of three boundary workers, comprised of politically sensitive, critical, but pragmatic scientists. They work for different organizations: an independent, multi-issue advisory body, a coordinating government department, and one of the larger consultancy firms. Factor 3 is highly correlated to Factor 1/facilitators (0.4980) and Factor 6/postnormal analysts (0.4737).

Like the rational facilitators, Factor 3 respondents are mild divergers (#4, +1; #5, 0). The gist of their position is that science and politics are indeed incompatible activities, both in terms of personal involvement and short- or long-term dynamics. To the extent socio-political functions of science and politics converge, this requires that science shakes politics and administration out of their “self-maintaining routines”. This attitude of challenge and contention is reflected in the three defining statements.

#18 To have party platforms checked by planning bureaus (scientific advisory agencies) is just too much! (+3).

#39 Critical analysis and policy-oriented learning make political ideologies more rational—and less important (−4).

#19 It is only natural to observe civil servants collaborating with scientists; after all, research is a link in the chain of policy implementation (−2).

All three defining statements capture this factor’s common denominator: concern with over-instrumentalization of government (#19), a narrow focus on the short-run and management fads (#39), and impoverishment of genuine political thought and debate (#18, #39). To counteract these tendencies, megapolicy strategists deem it important to take responsibility for fostering closer contacts and mutual trust between scientists and politicians and their policy staffers (#3, +4; #27, +4; #9, +3; #2, −4). They challenge them to think more critically about the assumptions underlying their decisions and actions, and to pay more attention to long-term impacts:

“Ultimately, we are boss! If we know something is policy-relevant, but they are embarrassed, or not yet convinced, we find this less important—it is our responsibility to stick to our judgment. …We have been visited by functionaries that claimed: ‘You ask dangerous questions; I will request my deputy minister to stop this research.’ Then I say: read the law and save yourself a lot of trouble; and thanks for the tip, for if you find our questions ‘dangerous’, they might be right on target.”

In short, boundary workers engaging in strategic megapolicy-type boundary discourse claim a government-oriented think-tank function, by verification and critical examination of strategic policy guidelines and assumptions, in light of most recent sound science and arguments, both in policy preparation and in the process of implementation.

Factor 4. Policy analysts (in public finance and economics-related policy domains): “We serve politics and policy with our up-to-date intelligence.”

Factor 4 is made up of three respondents, two of which (#20, #22) stand in obviously complementary roles as expert and policy advisor, in long-standing financial and economic policymaking networks; the other respondent (#19) is affiliated to a national institute for technology assessment.5 Factor 4 shows a high correlation with Factor 6/postnormal analysts (0.5398).

Policy analysts reject, contrary to knowledge brokers who embrace them, both convergent and divergent beliefs about (#4, −1; #5, −1). To the extent they can explain,6 the core reason is their view of politics. They not just express doubts, but flatly deny politics’ alleged function as creating conditions for cooperation. They see divisive and conflict-ridden power and interest struggle as the essence of politics. Factor 4 features four defining statements, three of which stress the autonomous role and responsibility of scientific expertise vis-à-vis other policy-relevant players in the financial-economic policy network and arena.

#41 Dealing with uncertainty primarily is a matter of thorough and honest political debate (−3).

The strong rejection of this statement implies that, contrary to beliefs of some other boundary workers, one should not leave matters of uncertainty to politicians and political debate, but claim uncertainty issues as an autonomous task for scientific expertise. Other defining statements are also strong denials.

#18 To have party platforms checked by planning bureaus (scientific advisory agencies) is just too much!7 (−4).

#23 The client or principal defines what knowledge is relevant (−4).

Rejecting statements #18 and #23 so forcefully can only be interpreted as a strong claim for an autonomous responsibility for scientific expertise in the long-standing rules and role structure of financial and socio-economic policymaking. How strong, was demonstrated by one respondent who, in a long monologue on correct role interpretation and rules for interaction and dialogue between scientific experts, policy advisors, stakeholders or interest association representatives, and political parties in Dutch democracy, stated:

“(Governmental, political) principals claiming that scientific experts do not strictly adhere to the letter of their terms of reference, ought to be called to order (italics by rh): ‘OK, but I think (this particular piece of information, rh) should be included, otherwise I would send a biased overall message.’ That is truly important; in that sense, you are not a mere policy implementer; your task (as scientific expert) is to transcend this.”

Other respondents stress the importance of evidence-based expertise in policymaking:

“Evidence-based policy is not yet much alive among Dutch policymakers. … Politicians don’t have an interest in having their policies critically assessed. But for me, to use available knowledge is key…It is the only thing you can do as policy scientist (italics by rh): providing intelligence on the basis of available knowledge.”

The last defining statement sets this factor apart from all other factors by claiming economics and public finance as the most relevant disciplinary basis of scientific knowledge:

#13 In my field, one scientific discipline dominates; when researchers or advisers from other disciplines come up with different, sometimes contradictory, recommendations, most of the time they prove to be useless (+2).

This is not necessarily because the policy analyst turns a blind eye to other disciplines’ contributions; rather, their reliance on economics and public finance is depicted as the outcome of a scientific ideal:

“My conviction, a scientific ideal perhaps, is that wise scientists and researchers ought to be able to arrive at a common judgment, irrespective of disciplinary backgrounds. …In practice, I observe the clashes, attributable to intentional or unconscious lack of communication. …Thus, as a description of reality I agree…But one ought not to accept it. Actually, it is a duty to make an effort to overcome it.”8

Capturing the core convictions in their discourse, one might say: in long-standing pragmatic relations and rules of the game, policy analysts provide politicians, civil servants, advisors and stakeholder representatives with evidence-based intelligence, i.e. information based on available and usable sound science, for their political judgments and decisions.

The remaining styles of discourse on boundary arrangements/practices are predicated on strong(er) ambitions for convergence in the political and societal function of politics and science.

Factor 5. Policy advisors (in public finance and economics-related policy domains): “We span the boundary between analysts and politicians.”

This factor counts two respondents, both high officials in their departments. They define a factor that has only low correlations to other factors. For Factor 5 respondents, called policy advisors, believe in convergent functions of politics and science is very modest indeed (#4, 0; #5, +1). From their shallow comments, it is clear that they actually do not have articulated positions: “Frankly, I never pose such questions to myself.” They just observe that science-based advice sometimes clashes with political judgments and decisions. Perhaps their weak preference for convergence is no more than an unreflective legitimation of their day-to-day work: “You don’t have to be an opportunist, do you?”

The two defining statements indicate that for policy advisors scientific knowledge and methods are an important foundation for good policy advice.

#12 It is admirable that scientists translate vague and inchoate political ideas and ideals into transparent models, and objectify them into measurable indicators (+4).

#2 Evidently, worthwhile policy ideas emerge from science; but scientists have no responsibility for their dissemination among or application by policy advising civil servants or politicians (+3).

But, read next to other statements (like #9, +3; #29, +3; #14, −3; #7, +3; #24, −3), it is clear that policy advisers’ discourse stakes out a claim of its own as spanning the boundary between analysts and politicians. This is borne out when looking at the final key statements of the interviews. Those statements are about realism and guarding against political and policy overreach by addressing administrative issues: acceptability and feasibility are theirs major themes in advice to ‘the Prince’, to be achieved through creation of more mutual understanding of political steering and implementation:

“(The major issue in boundary work is) improved mutual understanding; linked-up policy formulation and implementation; management of expectations, mitigation of exaggerated policy ambitions.”

The advisors’ role appears to be the bureaucratic counterpart to the role of a knowledge institute-based policy analyst. On the one hand, policy advisors advocate the use of evidence-based knowledge in politics and policymaking. Therefore, they—and not the analysts—bear responsibility for picking up sound, but usable knowledge (#29, +3). Policy advisers may even see it as their task to foster (more) usable knowledge in science. Claims one of the respondents: “We keep [our knowledge institute] on course.” Well-known and trusted scientists help forge compromise and coalitions in terms of content and arguments (#29, but also #12 and #15), but advisors do the mediation between scientists/analysts and policymakers (#2, #9). Thus, normative issues should be left to ‘us’ (politicians and policy advisors) (#7, −3); science has a role to play in uncertainty reduction (#24, −3), but does not have a monopoly (#14, −3).

Summarizing, it is clear that policy advisors advise political leaders about acceptability and feasibility of policy proposals, incorporating usable, best available knowledge on ‘what works’.

Factor 6. Postnormalists (in sustainability-related policy fields): “In a stable context of mutual trust, frictions breed value-added.”

With six boundary workers loading on this factor, it is the largest one All but one are ‘revolving door’ boundary workers; and they all work in sustainability-related policy domains (like agriculture, environment, food, nature conservation, natural resources, water management, etcetera) where ecology has become an important scientific background. Factor 6 has fairly high correlations with factor 1/facilitators (0.4363), factor 3/megapolicy strategists (0.4737), and factor 4/policy analysts (0.5398). Factor 6 lacks distinctive defining statements.

Factor 6 boundary workers hold self-conscious, but modestly convergent beliefs on the relationships between science and politics: the gap between the two is not taken-for-granted (#4, −2), and science and politics are, in the end, complementary (#5, +2). In the concluding key statements, it is clear that convergence is more of a desire or aspiration than reality.

“From experience, I believe the relation between policy and science is a must. But I also believe it to be incredibly tough. It requires mutual trust, and needs constant maintenance activities. Frequently, trust is created only if you meet over a fairly long period of time…”

“In my vision, interaction between science and politics should come from both sides…This is not at all self-evident. It takes so much effort (italics by rh). This attitude and intention to come to agreement, and to take time for good dialogue…this is very important. In my experience, over time, sometimes it works…But at other times the right people and/or circumstances are absent, and it is a complete failure.”

Comparing postnormalist analysts to policy analysts is illuminating. Policy analysts seem to be content in normal, applied, relatively monodisciplinary science (economics, public finance), whereas Factor 6 boundary workers are influenced by and attracted to a conception of interdisciplinary, postnormal science emerging in fields like ecology and other domains affected by complexity science (see differences on statements #13, #15). In the US and Canada too, it has been found that ecology-inspired scientists working in sustainability-related policy domains are open to views on science that are best described as ‘postnormal’ (Steel et al. 2004:9).

This difference is probably due to different policy issues and network conditions. Policy analysts operate in (socio-economic) policy networks with very elaborate, long-standing rule systems and stable role conceptions, while the postnormalists operate in (sustainability-related) issue networks where relationships are less clear, more volatile, and anything but settled. This may also well explain why postnormalists appear so preoccupied with the necessity and utility of trust in science-politics dialogue (#27, +4; #3, +3; #31, +3), integrated (multicriteria) assessment, well-defined, long-standing rules of the game (#25, −3), role conceptions, and personal qualities of boundary workers.

In their longing for stable relations, postnormalists stress the importance of acknowledging the primacy of politics; an attitude that manifests itself in very positively valued statements like politicians should decide on uncertainty (#8, +4; #34, +3), and on normative issues (#7, +3). But simultaneously, postnormalists adhere to a ‘speaking-truth-to-power’ heroism when they claim that science is not just serviceable, but has an autonomous responsibility (#25, −3), has a duty to disseminate results (#2, −3; #10, −3), and may even stamp political party platforms with a scientific seal of ‘good conduct’ (#18, −3). It looks like postnormalists, by embracing the primacy of politics and insisting on autonomous science at the same time, want to have their cake and eat it too. The normative beliefs about convergent political and societal functions serve as rhetorical justification for reconciliation of contradictory ideals.

Summarizing, postnormalists wish to create and institutionalize stable role and interaction patterns, so that scientists and policymakers may engage in productive, open dialogue, and integrated assessment of all pro’s and con’s and uncertainties surrounding sustainability issues.

Factor 7. Deliberative proceduralists: “Organize frank debate between robust parties.”

This factor is made up of one representative, ‘revolving door’ boundary worker active in health policy advice (Gr), and a double-loading, science-based boundary worker in sustainability-related issues (MNP). They are joined by one double-loading, policy-based boundary worker in technology assessment (Rathenau Institute), and one triple-loading, science-based boundary worker in sustainability-related policy sectors (MNP). Factor 7 has low correlations to other factors, indicating high autonomy.

On the basis of two defining statements (#35, #24) and a very positive score on statement #5(+4), deliberative analysts are designated as articulate and consistent convergers (#4, 0; #5, +4).

#5 No matter their differences, science and politics eventually serve a similar function: creating conditions for cooperation between people (+4).

#35 Uncertainty always finds its origin in normative and interpretive pluralism (+4).

#24 Uncertainty reduction through the use of science or expertise is hardly possible; learning is a matter of trial-and-error in practice (+3).

One respondent very self-consciously expressed this in his final key statement:

“Statements 4 and 5…forging coherence (italics by rh) is the essence of the process. …Scientific and normative issues just are not strictly separable…they cross over into each other. Hence, actors on both sides ought to cross borderlines.”

Combining quantitative data on very high and very low-scoring statements with a qualitative interpretation of key statements, Factor 7 boundary workers’ discursive style may be labeled as convergent proceduralism: active organization (#42, −4) of processes conforming to criteria for open and frank debate between robust parties, be they scientists, stakeholders, citizens (#6, −3), politicians, or even dissidents:

“Organizing robust parties…equally endowed with resources and skills…[engaging in debates on] problem structuring and solution structuring. Robust parties, for me, determine whether or not the process was a success.”

A comparison between postnormalist and deliberative proceduralist discourses increases understanding of both. Proceduralists are even more strongly idealistic about convergence than postnormalists (#5, +4 vs. +2). This translates into a more negative judgment about actual contacts between science and politics (proceduralists #3, −1; #9, −1; versus post-normalists #3, +3; #9, +2). But the major difference is in dealing with uncertainty. Proceduralists appear to argue: if science is about values too (#7, −4), and if uncertainty originates (most of the time, or in its most intriguing shapes9) in normative and interpretive ambiguity (#35, +4), convergence justifies that science should not (ultimately) leave normative and uncertainty issues to politicians (#8, −2). Thus, the client is and cannot be the sole arbiter of relevant knowledge (#23, −3)10. In subscribing to statement #35, proceduralists construct a strong connection between uncertainty and normative issues. In both cases, the question emerges: in addition, traditionally, to values, should one now also leave uncertainty to politicians? Postnormalists appear to answer ‘yes’ to both questions (#7, +3; #8, +4), but in both cases proceduralists say ‘no’ (#7, −4; #8, −2). This indicates a technocratic streak in proceduralism; after all, postnormalists strongly oppose having party platforms checked and (dis)approved by planning agencies (#18, −3), but proceduralists do not really mind (#18, 0).

Deliberative proceduralists may be characterized as saying: good boundary work requires a procedure and process-criteria that allow robust, but trusting parties, dissidents included, to fully and openly debate, each from their own perspective on the common good, policy proposals and their concomitant uncertainties as well as normative issues.

In conclusion, it can be said that the styles of boundary workers’ discourses can be differentiated quite clearly; they are empirically easily recognizable. With the exception of rational facilitators who are a motley company, other styles of boundary work discourse appear to be socially borne by fairly homogeneous sets of boundary workers. Hence, the overall pattern would allow the interpretation of “where you stand, depends on where you sit”. Variety and diversity is so strong, actually, that boundary workers with civil servant status inside government spread over five of the seven styles of boundary discourse.

What discourses fit the idealtypes best?

On the basis of inspecting most positive (+4, +3) and most negative statements (−4, −3), and tracing their derivations from the ideal typical models of boundary arrangements and practices, it is possible to trace considerable overlap between the empirical discourses of boundary work and the ideal typical models set out in Table 1 and Fig. 1 above.

Facilitators subscribe to coping and/or discourse coalition models and perhaps some engineering in the short run. But on the long run they hope for true learning. Knowledge brokers accept cognitive impairments of politics and bureaucracy as givens; as well as limitations of (social) science (no experiments possible), and the gap between politics and science. Yet, politically savvy scientists, with the assistance of brokers, may help remedy (some) impaired intelligence in other parties. In a realistic, or pessimistic (compared to all others) approach, knowledge brokers see reality as approximating the coping model, in which only instrumental learning is possible.

Megapolicy strategists clearly reject technocratic models. As long-term thinkers, they abhor testing of party platforms by planning agencies or knowledge institutes (#18), and do not believe in political ideologies becoming more rational and less important (#39). Firmly in the pragmatist camp, they support statements in line with the discourse coalition model (#27, 31). They nevertheless stress science’s independent function in dealing with (long-run) uncertainties (#8) and judging the relevance of knowledge (#23) – but not, apparently, values. Using autonomous research to check and criticize important policy assumptions, they intend to introduce new ones as building blocks for discourse coalitions between far-sighted (non-technical) scientists and politicians interested in the long range.

Highly positive and negative statements by policy analysts are a mixture of ideal types. There is support for pragmatist-decisionist attitudes (##3, 27, and 25) that result from long-standing rules of the game of Dutch corporatist-democratic practice in financial and socio-economic policymaking. On the other hand, they openly incline to technocracy in their defining statements (##13, 15, 23; but also 18 and 25). Other positively valued statements, (like #3, #30, #24, #41) can be interpreted as technocracy posing as learning. Perhaps, such a mix should be called a form of moderate and pragmatic technocracy that is tolerated,invited even, by politics, as long as it is deemed usable or ‘serviceable’ (Jasanoff 1990) to the functioning of the politico-economic system.

Policy advisors demonstrate the same leanings towards technocracy and evidence-based, sound science as policy analysts (##12, 15, 9, 29); but working from an inside-bureaucratic position, advisors stress their service to politics and policy (##7, 9, 30), partly as justification for an active mediation role (##2, 9, 29, 14). Advisors cast themselves in the role of ‘boundary spanners’ between policy analysts and politicians. Perhaps a complex mixture or continuing balancing act between technocracy (when using analysts’ intelligence) and bureaucracy models (when serving their political masters) best captures their type of boundary work.

Representing sciences/disciplines where until recently enlightenment and technocracy models enjoyed much popularity among scientists, and bureaucracy models governed their practice as boundary workers, the political salience and societal relevance of sustainability issues is now pressing postnormal analysts to find other, workable models for boundary arrangements and practices. Pounding simultaneously on the theme of more pragmatism (#3, #10) and autonomous, critical, but constructive science (#25, −3; #2, −3; #10, −3), they show some attraction to the advocacy and discourse coalition models (#27, +4; #31, +3; #34, +3). But they also bow to decisionism (either bureaucracy, or engineering) by stressing that normative and uncertainty issues, after an open and comprehensive debate of pros and cons, should ultimately be dealt with through political preferences and decisions (#8, +4; #7, +3). Where postnormalists favor the checking of party platforms (#18, −3) (also see under factor 7), advocacy of and discourse coalition building for policy on the basis of ecological insights may even express itself as technocracy. Maybe they interpret it as another platform for dialogue with politicians.

Deliberative proceduralists are the most convergent thinkers of all boundary workers (#5, =4). They have affinities with models like coping (#24, +3) (probably as description of how policy learning—#42, −4—and uncertainty in data/models work now), advocacy (#24, +3; #34, +3) and discourse coalitions (#35, +4; #31, +3). The overall impression is that deliberative proceduralists want to move away from perceived reality as coping and advocacy, towards organized, stable discourse coalitions or learning between scientists and politicians/policymakers.

Discussion

Findings allow the conclusion that there are considerable resemblances between the actual discourses and the ideal types. Except for the enlightenment ideal type, elements and parts of all other ideal types are recognizably referred to by Dutch boundary workers. Judging from the examples and anecdotes mentioned, this is not a research artifact. But one should be careful not to project the discourses on the academic cartography. Only two discourse types appear to have a one-to-one relationship to an ideal type: strategists to discourse coalition models, and brokers to coping. All other discourse types are found to mix and merge ingredients of at least two different ideal types. Moreover, in their discourses boundary workers mix descriptive and normative elements. Postnormalists and deliberative proceduralists provide typical examples; from a reality experienced as adversarial and coping, they aspire to stable discourse coalitions or learning. The strong rejection of adversarial models, and the modest, instrumental adherence to engineering, both part of the working consensus among all types of boundary workers, clearly have a normative ring.

More importantly, the convergence/divergence axis in the academic typology is fuzzy in the eyes of boundary workers. As mentioned in the previous sections, most of them expressed difficulties and hesitations in answering to the relevant statements (esp. #4, #5). The result was a lot of scores in the middle range (−1, 0, +1), except for postnormalists (#4, −2; #5, +2) and proceduralists (#4, 0; #5, +4), for whom convergence clearly was a strong ambition. Yet, indifference or ‘don’t know’ are too shallow interpretations of the answers’ meanings. An important indication is that it is impossible to literally project discourses found on the map of ideal types. Postnormalists and advisors mention relatively high convergent ideal types, but technocratic-minded analysts clearly reject it, stressing operational code divergence instead. Deliberative proceduralists are the most convergent boundary workers; yet, looking at ingredients of ideal types mentioned, they hover somewhere around the center point of the convergence/divergence axis, but slightly to the primacy for politics side. Brokers timidly embrace both convergence and divergence; yet, position themselves in the coping model in a convergent quadrant of the typology.

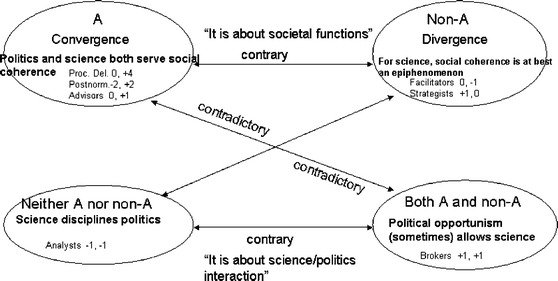

Perhaps a rethinking of the convergence/divergence axis in light of the semiotic square (Roe 1994; Van Eeten 2000) is in order. The semiotic square expresses the insight that the meaning of a concept (“A” = convergence) is only fully revealed when taking into account it contrary position (“non-A” = divergence), and both of their contradictions (“neither A nor non-A”; “both A and non-A”). In this case, allowing the strongest or most graphic responses to statements #4 and #5 to determine the meanings implied, the semiotic square looks like in Fig. 2. In interpreting the convergence-divergence axis (statements ##4 − 5) some boundary workers were thinking of social functions, others of codes of operation in science and politics.

Fig. 2.

Semiotic square of the meaning of convergence/divergence in basic attitudes of boundary workers

Conclusion

The overall picture emerging from the descriptions of the seven discursive styles confirms a contingency view of boundary arrangements and practices. Variety and diversity, within the bounds of shared institutional opportunities and constraints reflected in the working consensus, showed up already in the theoretical reconstructions and more qualitative discourse analysis of a restricted number of cases (Hoppe and Huijs 2003), and in more historical-institutional analysis of the arrangements of politics/science boundaries in the Dutch political system of the last 30 years (Halffman and Hoppe 2005). No doubt, other political systems with different histories, academic traditions, and science/politics linkages will feature other types of boundary work and arrangements. In view of the relative scarcity of empirical research into the perspectives and discourses of boundary workers themselves, comparative research on this topic, within and outside Europe, appears an interesting and promising line of research.

This is all the more so since there appear to emerge from this research two challenges for the future governance of expertise. First, uncertainty issues are a new ‘battlefield’ in the division of labor between politics/policy and science/expertise. Contrary to normative issues that are formally dealt with by the ‘noble lie’ of bowing to a decisionist ‘primacy of politics’, boundary workers appear to disagree among themselves on how best to handle uncertainty. On the one side, policy analysts and megapolicy strategists insist on expert autonomy; whereas facilitators and, to a lesser extent, knowledge brokers would bow to the primacy of politics. This is true as well for postnormalists who feel uncertainty issues have to be decided upon by political criteria, whereas deliberative proceduralists definitely would like to have their own say.

Second, the knowledge and assessment agencies employing boundary workers are faced with a changing, more pluralistic political landscape. They now generally work in alliance with national government. But they face an expanding number of increasingly vociferous civil society organizations and stakeholders, like non-governmental organizations. Also, they need to position themselves vis-à-vis supranational levels of government (e.g. the European Commission’s Bureau of European Policy Advisers, BEPA) and the knowledge institutes and think tanks operating at the international level (like the OECD, IMF, World Bank, Eurostat, etcetera). Ambiguities among boundary workers’ beliefs on allowing lay or practitioners’ knowledge standing at the policy tables, and on dealing with supranational levels of government, suggest they are aware of the problems. Yet, it will take quite some ingenuity to find satisfactory strategies between not antagonizing traditional governmental clients and coping with the value and knowledge pluralism of the new multi-actor and multi-level governance structures.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix 1

Q-statements, rank-ordered per normalized factor-score, and distinguishing statements per factor

| Q-statement #// factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Distinguishing statement for factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Without clear terms of reference and an alert supervisory committee, scientific researchers and advisors would just ride their hobbyhorses | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 2 | 0 | |

| 2. Evidently, worthwhile policy ideas emerge from science; but scientists have no responsibility for their dissemination among or application by policy advising civil servants or politicians | −1 | 0 | −4 | −2 | 3 | −3 | −2 | 5 |

| 3. In our policy sector, civil servants, politically accountable administrators, and science-based advisers are in close contact with each other | −1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | −1 | |

| 4. It is in the nature of things that politics and science are incompatible activities | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 | −2 | −1 | |

| 5. No matter their differences, science and politics eventually serve a similar function: creating conditions for cooperation between people | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| 6. When the chips are down, lay and practitioners’ knowledge have less value than scientific knowledge; therefore, they deserve no standing at the policy table | −3 | −2 | −3 | −1 | −4 | −1 | −1 | |

| 7. Normative issues are outside science, and should be left to politics | −4 | 0 | −1 | 3 | −3 | 3 | −4 | |

| 8. As a scientist you ought to be aware of the margins of uncertainty around scientific knowledge; but one should leave it to politicians to decide how to deal with uncertainty | 3 | −3 | −3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | −2 | |

| 9. ‘Unknown, unloved’ is certainly true for the relation between scientists and policymakers/politicians | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | −1 | |

| 10. Politics and/or policy learn from science only by chance, if at all | −3 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −4 | −3 | −1 | |

| 11. Depoliticizing an issue usually if beneficial; too often good policy advice is spoiled by politics | −1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −2 | −3 | |

| 12. It is admirable that scientists translate vague and inchoate political ideas and ideals into transparent models, and objectify them into measurable indicators | −2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 13. In my field, one scientific discipline dominates; when researchers or advisers from other disciplines come up with different, sometimes contradictory, recommendations, most of the time they prove to be useless | 0 | −3 | −2 | 2 | 0 | −4 | −1 | 4 |

| 14. Uncertainty should be reduced through use of quantitative analytical methods; if this proves to be impossible, you need to program more research to make progress | 0 | −2 | 0 | 1 | −3 | −1 | −2 | |

| 15. If you desire policy-oriented learning, you should design experiments | 1 | −4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 16. ‘Policy-oriented learning’ is a ‘motherhood’ or ‘apple-pie’ concept: who could be against it, if only you may determine yourself what constitutes ‘learning’? | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| 17. Far-sighted scientists and technical specialists initiate developments that politics will only legitimize after the fact | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 18. To have party platforms assessed by planning bureaus (scientific advisory agencies) is just too much! | 0 | −2 | 3 | −4 | −2 | −3 | 0 | 3 |

| 19. It is only natural to observe civil servants collaborating with scientists; after all, research is a link in the chain of policy implementation | 1 | 1 | −2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 20. It is not for nothing that scientific conflicts or inconsistencies frequently run parallel to boundaries between departments, agencies, or other bureaucratic units | 1 | −1 | 2 | −1 | −2 | 1 | −3 | |

| 21. Scientists and experts experience difficulties working for or in government, as government honors and needs their professional skills, but simultaneously demands their full loyalty | 2 | −3 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −2 | |

| 22. Scientific knowledge should be seen as information that, when en where available, can be purchased at a reasonable price | −1 | 0 | −2 | 0 | −2 | −1 | −2 | |

| 23. The client or principal defines what knowledge is relevant | 0 | −2 | −3 | −4 | 1 | 0 | −3 | |

| 24. Uncertainty reduction through the use of science or expertise is hardly possible; learning is a matter of trial-and-error in practice | −2 | −3 | −2 | −3 | −3 | −1 | 3 | 7 |

| 25. The right relationship between politics/policy and science is one of agent and principal in a well-defined project | −2 | 1 | −1 | −4 | 0 | −3 | −3 | |

| 26. In outsourcing research it is difficult to create a relationship of mutual trust | −1 | −2 | −1 | 0 | −2 | −2 | −2 | |

| 27. Mutual trust between politicians/policymakers and scientists/experts differs from case to case and needs continuous maintenance | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |

| 28. Scientific experts and advisers are lawyers: their business is advocacy for political positions | −4 | −4 | −4 | −3 | −1 | −4 | 0 | |

| 29. Most of the time it is concepts, models or story lines originating in science that are the glue in political compromise, or the pragmatic ties holding coalitions together | 1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| 30. In politics, normative issues emerge as infringements on vested interests | −3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | −4 | 1 | 1 | |

| 31. Normative issues are difficult to grasp; people discover values only in dialogue with or comparison to other people | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| 32. Science and expertise have the political function of a ‘refrigerator’ for issues that, for some reason or another, are ‘too hot to handle’ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 33. In the competition between scientific disciplines, the most politically useful knowledge is the winner | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 34. Uncertain knowledge defines the free decision space for political action | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| 35. Uncertainty always finds its origin in normative and interpretive pluralism | −2 | −2 | 0 | −1 | −2 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| 36. Policymaking is about coping with, or dealing with problems so that they do not get out of hand | 2 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 2 | |

| 37. In public policy, learning is limited to instrumental, financial and organizational matters | −2 | 4 | 0 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 2 |

| 38. Politicians and policymakers correctly trust the common sense of experienced practitioners more than experts’ insights | −3 | 0 | −2 | −2 | 0 | −1 | 1 | |

| 39. Critical analysis and policy-oriented learning make political ideologies more rational—and less important | 3 | 0 | −4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 40. There will always be a political struggle about values; and correspondingly, types of knowledge that align with, or deviate from political value systems | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 41. Dealing with uncertainty primarily is a matter of thorough and honest political debate | 2 | 2 | 0 | −3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 42. To the extent politics and policy can be said to learn from science, this happens through spontaneous convergence between political and scientific debates | 1 | −1 | 0 | −2 | 0 | −2 | −4 |

Appendix 2

Correlation matrix between factors

| Correlations between factor scores | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1 | 1.0000 | 0.1927 | 0.4980 | 0.2257 | 0.3437 | 0.4363 | 0.2307 |

| 2 | 0.1927 | 1.0000 | 0.3136 | 0.0905 | 0.2043 | 0.3421 | 0.1529 |

| 3 | 0.4980 | 0.3136 | 1.0000 | 0.3096 | 0.2241 | 0.4737 | 0.2665 |

| 4 | 0.2257 | 0.0905 | 0.3096 | 1.0000 | 0.2077 | 0.5398 | 0.1628 |

| 5 | 0.3437 | 0.2043 | 0.2241 | 0.2077 | 1.0000 | 0.3804 | 0.2656 |

| 6 | 0.4363 | 0.3421 | 0.4737 | 0.5398 | 0.3804 | 1.0000 | 0.2974 |

| 7 | 0.2307 | 0.1529 | 0.2665 | 0.1628 | 0.2656 | 0.2974 | 1.000 |

Appendix 3

Factor loadings of respondents

Factor loadings with an X indicating a defining sort Underlined respondents load (weakly) on more than one factor

| QSORT | Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1 MNP | 0.3489 | 0.1640 | −0.1296 | 0.2914 | 0.0459 | 0.3980 | 0.4219 |

| 2 LNV | 0.1309 | 0.3802 | 0.0698 | 0.3098 | 0.0477 | 0.6184X | 0.1756 |

| 3 exGr | 0.0620 | −0.0374 | 0.1336 | 0.0228 | 0.1429 | 0.1143 | 0.7965X |

| 4 Bers | 0.0297 | 0.1520 | 0.6830X | 0.1166 | 0.0279 | −0.0548 | 0.3953 |

| 5 MNP | 0.2907 | 0.1928 | 0.0902 | 0.1233 | 0.1321 | 0.5100 | 0.5350 |

| 6 exBiZa | 0.0326 | 0.7769X | 0.1928 | −0.0296 | 0.0260 | 0.1738 | 0.1067 |

| 7 Fin | 0.1374 | 0.2730 | −0.1002 | 0.1514 | 0.8418X | 0.0920 | 0.1384 |

| 8 exVWS | 0.1397 | −0.2244 | 0.3158 | −0.0683 | 0.6841X | 0.3064 | 0.2119 |

| 9 CPB | 0.6620X | 0.0921 | 0.0866 | 0.4719 | 0.2518 | 0.1266 | 0.1982 |

| 10 WRR | 0.3238 | −0.0405 | 0.7315X | 0.3019 | 0.1039 | 0.1748 | −0.0101 |

| 11 WUR | 0.3403 | −0.0444 | 0.2270 | 0.2164 | −0.1160 | 0.6779X | 0.2992 |

| 12 AZ | 0.2133 | 0.2340 | 0.7069X | −0.0504 | 0.0057 | 0.3091 | 0.0053 |

| 13 AZ | 0.5052 | −0.2146 | 0.3378 | 0.0714 | 0.2359 | 0.5195 | 0.0776 |

| 14 WRR | 0.6383X | −0.0913 | 0.1738 | 0.1974 | 0.3569 | −0.0692 | 0.0960 |

| 15 MNP | 0.3302 | 0.0967 | 0.1274 | 0.2383 | 0.2984 | 0.6221X | −0.0933 |

| 16 RVG | 0.8281X | 0.1659 | 0.2296 | −0.1722 | −0.0673 | 0.2113 | 0.1012 |

| 17 VROM | 0.5103 | 0.3094 | 0.3178 | 0.1839 | 0.0370 | 0.2554 | 0.3922 |

| 18 VROM | 0.3736 | 0.5066 | 0.0024 | 0.1180 | 0.3235 | 0.4249 | −0.2085 |

| 19 RAT | 0.2354 | 0.2295 | 0.2735 | 0.5284 | 0.2454 | −0.0177 | 0.4625 |

| 20 FIN | 0.1131 | −0.2334 | 0.0357 | 0.8177X | −0.0381 | 0.2752 | −0.0062 |

| 21 exWUR | −0.2047 | 0.2426 | 0.1285 | 0.1045 | 0.1710 | 0.7239X | 0.1280 |

| 22 CPB | −0.0415 | 0.3198 | 0.2183 | 0.6881X | 0.1400 | 0.3025 | 0.1365 |

| % expl.Var. | 13 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 15 | 9 |

| ∑ 73% | |||||||

Appendix 4

Structured P-sample

| Science-based boundary workers: 9 |

| Nr. 21 exWageningen University and Research Centre (WU/R) |

| Nr. 11 WU/R, |

| Nr. 5 MNP, |

| Nr. 14 Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR), |

| Nr. 9 CPB, |

| Nr. 10 WRR, |

| Nr. 4 Berenschot Consultancy, |

| Nr. 22 CPB, |

| Nr. 1 MNP |

| Policy-based boundary workers: 7 |

| Nr. 13 Ministry of General Affairs (AZ), |

| Nr. 17 Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM), |

| Nr. 18 VROM, |

| Nr. 20 Ministry of Finance (FIN), |

| Nr. 19 the Rathenau Institute (RATH), |

| Nr. 7 FIN, |

| Nr. 8 exMinistry of Traffic, Public Works, and Water Management (VWS) |

| Double-based, ‘revolving door’ boundary workers: 6 |

| Nr. 2 Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV), |

| Nr. 15 MNP, |

| Nr. 16 Council for Public Health and Health Care (RVZ), |

| Nr. 6 exMinistry of Interior Affairs and Kingdom Relations (BZK), |

| Nr. 12 AZ, |

| Nr. 3 exHealth Council (Gr) |

Footnotes

In the case of boundary work one may seriously doubt the statistical meaning of any claim to representativeness of a ‘sample’ of boundary workers. To claim a sample’s representativeness, one has to be able to meaningfully define the entire population of boundary workers – a daunting task to begin with.

The larger research project is called Rethinking Political Judgment and Science-Based Expertise: Boundary Work at the Science/Politics Nexus of Dutch Knowledge Institutes, funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO-grant 410.42.16P).

Using standard statistical procedures in PQMETHOD (downloadable from http://www.lrz-muenchen.de/~schmolck/qmethod/). To check the results, I also performed a centroid cluster analysis, varimax on seven factors. Explained variance decreased from 73 to 53%; the number of factors decreased from seven to six; but these six were hard to interpret, in contrast to the seven factors to be presented.

Several respondents stress that one may not turn the statement around: politicians, in their view, are not actively looking for scientific uncertainty in order to increase their political scope of decision-making and action.

This respondent also loads in Factor 7, the deliberative proceduralists.

An illustrative policy analytic statement: “Where I have less articuated beliefs, and where I feel less at home, is statements about different types of knowledge; the type of philosophy of science issues behind them…”

Both the Center for Economic Policy Analysis and the Environmental Assessment Agency assess political party platforms in terms of goals achievement, consistency with budget forecasts, and EU maximum deficit norms. Allegedly, this speeds up later cabinet formation negotiations between political parties (Halffman and Hoppe 2005).

When economics-trained policy scientists relativize their neopositivist ideals, fruitful debate with post-normal scientists is clearly possible. This may explain the relatively high correlation between factors 4 and 6 (Appendix 2).

“Not always. Uncertainty also has its sources in variability and other boring things. But the most intriguing and entertaining forms of uncertainty stem from value pluralism…”

“That is what government principals would like…But let me give you an example from the Health Council. We always explicitly made the point that there had to be interaction (between government and experts, rh), during problem structuring, in the models for risk calculation and risk assessment…”

References

- Bal R. Grenzenwerk. Over het organiseren van normstelling voor de arbeidsplek. Enschede: Twente University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bal R, Halffman W (eds) (1998) The politics of chemical risk: scenarios for a regulatory future. Kluwer, Dordrecht

- Bal R, Bijker W, Hendriks R. Paradox van Wetenschappelijk Gezag: over de Maatschappelijjke Invloed van de Gezondheidsraad. Den Haag: Gezondheidsraad; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bemelmans-Videc M-L (1984) Economen in Overheidsdienst. Bijdragen van Nederlandse Economen aan de Vorming van het Sociaal-Economisch Beleid, 1945–1975.Vakgroep Bestuurskunde, Rijksuniversiteit Leiden (dissertation)

- Brown SR. Political subjectivity: applications of Q-methodology in political science. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- CPB/MNP/Rand Europe (2008) Dealing with uncertainity in policymaking. Bilthoven

- den Butter FAG, Morgan MS (eds) (2000) Empirical models and policy making: interactions and institutions. Routledge, London

- Diesing P. How does social science work? Reflections on practice. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ezrahi Y. The descent of Icarus. Science and the transformation of contemporary democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller S (2001) Strategies of knowledge integration. Our fragile World: challenges, opportunities for sustainable development. Tolba MK (ed) EOLSS Publishers (for UNESCO), Oxford, pp 1215–1228

- Halffman W. Boundaries of regulatory science. Eco-toxicology and aquatic hazards of chemicals in the US, England, and the Netherlands, 1970–1995. Boechout: Albatros; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Halffman W, Hoppe R. Science/policy boundaries: a changing division of labour in Dutch expert policy advice. In: Maasen S, Weingart P, editors. Democratization of expertise? Exploring novel forms of scientific advice in political decision-making. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2005. pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe R. Van Flipperkast Naar Grensverkeer. Veranderende Visies op de Relatie tussen Wetenschap en Beleid. AWT Achtergrondstudie nr. 25. Den Haag: Adviesraad voor Wetenschap en Technologiebeleid; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe R (2002b) Rethinking the puzzles of the science-policy nexus: Boundary traffic, boundary work and the mutual transgression between STS and Policy Studies. In: Paper prepared for the EASST 2002 Conference, ‘Responsibility under Uncertainty’, York, 31 July–3 August

- Hoppe R. Rethinking the science-policy nexus: from knowledge utilization and science technology studies to types of boundary arrangements. Poièsis and Praxis. Int J Technol Assess Ethics Sci. 2005;3(3):119–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe R, Huijs S (2003) Werk op de grens tussen wetenschap en beleid: paradoxen en dilemma’s, Rapport nr. 54, Den Haag: Raad voor Ruimtelijk, Milieu- en Natuuronderzoek (RMNO)

- Jasanoff S. The fifth branch: science advisers as policy makers. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown B, Thomas D. Q methodology. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Meltsner A. Rules for rulers. The politics of advice. Philadelphia: Temple UP; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Powell MR (1999) Science at EPA. Information in the regulatory process, Resources for the future, Washington, DC

- Renn O. Styles of using scientific expertise: a comparative framework. Sci Publ Policy. 1995;22(3):147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Roe E (1994) Narrative policy analysis. Theory and praxis. Duke University Press, Durham and London

- Schmutzer MEA (1994) Ingenium und Individuum. Eine sozialwissenschaftliche Theorie von Wissenschaft und Technik. Springer, Wien