Abstract

Background

The relationship between marijuana smoking and pulmonary function or respiratory complications is poorly understood; therefore, we conducted a systematic review of the impact of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications.

Methods

Studies that evaluated the effect of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications were selected from the MEDLINE, PsychINFO, and EMBASE databases according to predefined criteria from January 1, 1966, to October 28, 2005. Two independent reviewers extracted data and evaluated study quality based on established criteria. Study results were critically appraised for clinical applicability and research methods.

Results

Thirty-four publications met selection criteria. Reports were classified as challenge studies if they examined the association between short-term marijuana use and airway response; other reports were classified as studies of long-term marijuana smoking and pulmonary function or respiratory complications. Eleven of 12 challenge studies found an association between short-term marijuana administration and bronchodilation (eg, increases of 0.15–0.25 L in forced expiratory volume in 1 second). No consistent association was found between long-term marijuana smoking and airflow obstruction measures. All 14 studies that assessed long-term marijuana smoking and respiratory complications noted an association with increased respiratory symptoms, including cough, phlegm, and wheeze (eg, odds ratio, 2.00; 95% confidence interval, 1.32–3.01, for the association between marijuana smoking and cough). Studies were variable in their overall quality (eg, controlling for confounders, including tobacco smoking).

Conclusions

Short-term exposure to marijuana is associated with bronchodilation. Physiologic data were inconclusive regarding an association between long-term marijuana smoking and airflow obstruction measures. Long-term marijuana smoking is associated with increased respiratory symptoms suggestive of obstructive lung disease.

Marijuana remains the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States, with 14.6 million people 12 years and older reporting current use.1 The prevalence of marijuana abuse and dependence continues to increase and occurs in 18% of past-year marijuana users.2 Given the persistently high prevalence of marijuana use, abuse, and dependence in the community, it is important to understand the potential adverse health outcomes that result from both short-term and long-term marijuana smoking.

Marijuana and tobacco smoke share many of the same compounds. Tobacco smoking is associated with numerous adverse pulmonary clinical outcomes, affecting both pulmonary function and respiratory complications. Some of the known tobacco smoking–related adverse effects include cough, chronic bronchitis, impairment of gas exchange, and airway obstruction that leads to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3,4 The adverse impact of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications has not been systematically assessed. The purpose of the current review is to determine the association between short-term marijuana smoking and airway response and the association between long-term marijuana smoking and pulmonary function or respiratory complications.

METHODS

SEARCH STRATEGIES

English-language studies in persons 18 years or older were identified from the MEDLINE, PsychINFO, and EMBASE databases from January 1, 1966, to October 28, 2005, using medical subject headings and text words (see Appendix at http://www.tresearch.org/add_health/lit_reviews.htm). Only studies that involved marijuana smoking were considered for review.

SELECTION

Retrieval of studies was performed by 2 reviewers (B.A.M. and R.M.), who evaluated titles and abstracts from the initial electronic search of potentially relevant articles. Studies were excluded if they did not report primary data, did not include human subjects, did not report results of respiratory complications or pulmonary function tests, or reported on a case series with fewer than 10 subjects. For studies that presented data on similar or duplicate cohorts, we used data that represented the last follow-up for the cohort or findings from investigations that represented assessments of unique domains or variables. Articles that could not be categorized based on review of the abstract were evaluated in manuscript form. Studies with discordant categorizations by the 2 reviewers were resolved in collaboration with a third reviewer (D.A.F., K.C., or J.M.T.) to reach consensus.

VALIDITY ASSESSMENT

Study quality was evaluated by 2 reviewers (J.M.T. and K.C.) using an established generic instrument5 that assessed reporting, bias or confounding, and power; a score of 12 or higher was considered good study quality.5 We also applied exposure and disease-specific criteria to augment quality assessment using the generic instrument. For cross-sectional studies, these criteria were whether data were included on prior tobacco exposure and on dose and duration of marijuana exposure and whether a standardized method to assess the pulmonary outcome of interest was used. For observational cohort studies, an additional criterion was to screen patients at baseline and exclude those with the outcome of interest. Challenge studies needed to meet the criteria listed herein and also mask patients and study personnel to marijuana use. Differences between reviewers were resolved by consensus with input from a third reviewer (J.C. or D.A.F.). Interrater reliability was high (r = 0.79 for the generic evaluation criteria; r = 0.89, Kendall τ = 0.85; P<.001 for the exposure and disease-specific criteria).

DATA SYNTHESIS

The heterogeneous nature of the studies and their outcomes precluded quantitative synthesis (ie, meta-analysis). Therefore, this review focuses on a qualitative synthesis of the data.

DATA ABSTRACTION

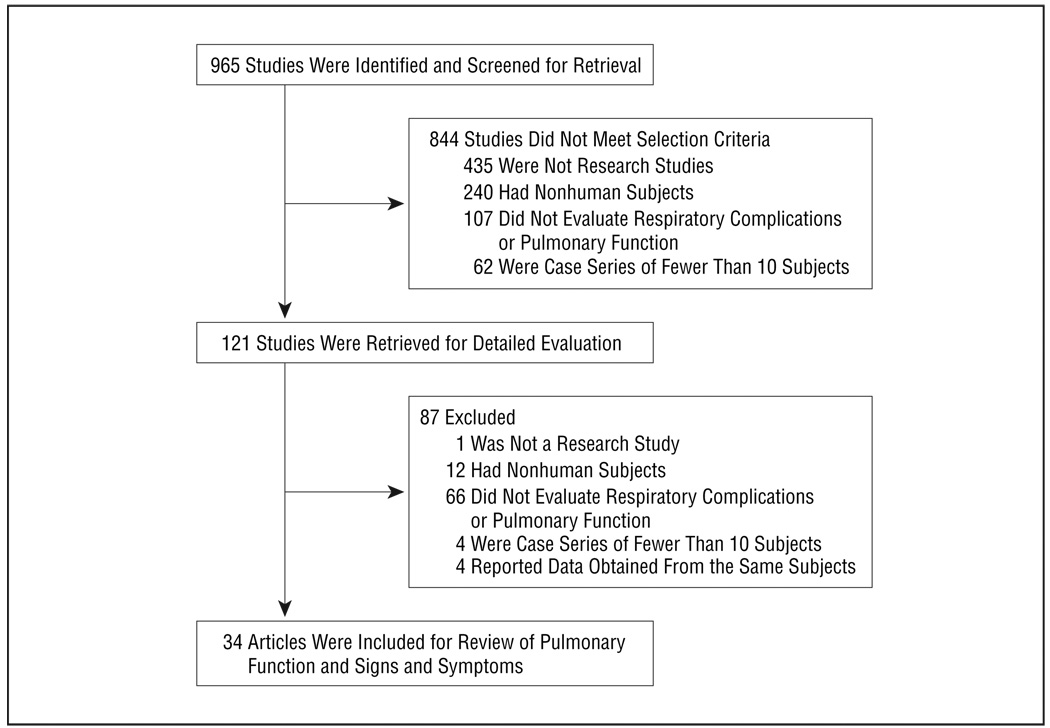

The initial literature search identified 965 citations. Inconsistencies regarding assessment of eligibility criteria were discussed by the whole team. Of the 965 abstracts initially reviewed, 931 were not relevant: 436 did not report primary data, 252 did not include human subjects, 173 lacked evaluation of respiratory complications or pulmonary function tests, 66 were case series of fewer than 10 patients, and 4 reported data obtained from the same patients. Ultimately, 34 unique articles were included in the review (Figure).

Figure.

Literature search results.

The outcomes of the 34 included studies were classified into 3 non–mutually exclusive categories: airway response to experimentally administered marijuana (challenge studies),6–17 changes in pulmonary function secondary to long-term marijuana smoking,18–31 and respiratory complications secondary to long-term marijuana smoking.18,20,22,24,28,31–39 The studies reviewed had diverse study designs; 12 studies had a laboratory challenge study design,6–17 15 were cross-sectional,* 3 were observational cohort studies,24,26,29 3 were case series,20,33,39 and 1 was a case-control study.32

RESULTS

REVIEW OF STUDIES CATEGORIZED BY STUDY OUTCOME

Short-term Marijuana Use and Airway Response

Twelve studies (Table 1) assessed the impact of short-term marijuana use on airway response. The studies used various measures to evaluate airway response: specific airway conductance (sGaw) (a measure that is inversely related to airway resistance), 6,7,9,12,14–16 forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1),9–11,14,15 peak flow,8 airway resistance,17 and change in methacholine- and exercise-induced bronchospasm.13

Table 1.

Challenge Studies That Reported Effects of Short-term Marijuana Inhalation on Airway Response

| Source | No.of Subjects |

Results | Control for Confounding |

Mean Generic Quality Score |

Mean Exposure and Disease-Specific Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vachon et al,6 1974 | 10 | Marijuana smoking associated with increase in sGaw 1 h after smoking (P<.001) | None | 8 | 1.5 |

| Tashkin et al,7 1974 | 10 | After smoking marijuana, average sGaw increased immediately (P<.05 compared with controls and placebo) in patients with asthma | Tobacco | 11.5 | 3 |

| Bernstein et al,8 1976 | 28 | 12 of 15 subjects showed increases in peak expiratory flow immediately after smoking a marijuana cigarette | None | 7 | 2 |

| Laviolette and Belanger,9 1986 | 11 | Marijuana smoking produced increase in sGaw (P<.01) and FEV1 (P<.05) | Tobacco | 10 | 2.5 |

| Renaud and Cormier,10 1986 | 12 | FEV1 increased immediately after marijuana smoking (P<.01) | None | 12 | 3 |

| Steadward and Singh,11 1975 | 20 | No difference in FEV1 after smoking marijuana compared with baseline or placebo | None | 15 | 2 |

| Tashkin et al,12 1973 | 32 | After smoking marijuana, there was an immediate inrease in sGaw, which peaked at 15 min after smoking and remained elevated at 60 min | Tobacco | 16.5 | 3 |

| Tashkin et al,13 1975 | 8 | After both methacholine-induced and exercise-induced bronchospasm in asthmatic patients, marijuana caused correction of bronchospasm and associated airway hyperinflation | Tobacco | 13 | 3 |

| Tashkin et al,14 1976 | 28 | After 47 to 59 d of heavy marijuana smoking, mean FEV1 decreased (P<.01) and mean sGaw decreased (P<.001). Modest but significant decrease in diffusing capacity also noted. Correlation between average quantity of daily marijuana smoked during the study and reduction of sGaw. | Tobacco | 9 | 3 |

| Tashkin et al,15 1977 | 11 | FEV1 and sGaw increased after smoked marijuana (P<.05) | Tobacco | 14.5 | 3 |

| Vachon et al,16 1973 | 17 | Increase in sGaw after marijuana inhalation | Tobacco | 17 | 3 |

| Wu et al,17 1992 | 23 | After smoking marijuana, airway resistance decreased significantly at all levels of marijuana compared with placebo (P<.05) | Tobacco | 17.5 | 3 |

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; sGaw, specific airway conductance.

Among the 7 studies that used sGaw to assess the airway response to marijuana challenge, 6 studies6,7,9,12,15,16 showed an increase in sGaw after marijuana challenge that ranged from 8% to 48%. Two of these studies6,12 showed that the increase in sGaw lasts up to 60 minutes after marijuana administration, and 1 study12 demonstrated that peak sGaw occurred 15 minutes after smoking.

Among the 5 studies that used FEV1 to assess airway response to marijuana challenge, 3 studies9,10,15 showed an increase in FEV1 after smoking marijuana compared with baseline, ranging from 0.15 to 0.25 L. One study11 showed no difference in FEV1 after marijuana challenge compared with baseline or placebo.

One study8 used peak flow to assess marijuana effect on airway response and showed that 12 of 15 patients had an increase in peak flow immediately after marijuana inhalation, with a mean ± SD prechallenge vs postchallenge peak flow of 509.2 ± 76.1 vs 549.2 ± 66.4 L/min × 100, respectively (P<.05). Another study17 showed a mean ± SD decrease in airway resistance after marijuana smoking compared with placebo (2.08±0.36 cm H2O/L per second for low-dose marijuana smoking vs 1.49±0.26 cmH2O/L per second for placebo and 1.97±0.35 cm H2O/L per second for high-dose marijuana smoking vs 1.18±0.14 cm H2O/L per second for placebo; P<.05 for both comparisons). Finally, a third study13 showed immediate reversal of both methacholine-induced and exercise-induced bronchospasm in patients with asthma after marijuana challenge.

One study14 examined the impact of a more prolonged exposure to marijuana on airway response, in which subjects smoked marijuana ad libitum for 47 to 59 days in a sequestered environment. In contrast to the short-term exposure studies, this study demonstrated a decrease in sGaw compared with baseline (change of 16% ± 2%; P<.001) after the more prolonged exposure to marijuana, as well as a decrease in FEV1 compared with baseline. This study also demonstrated a correlation between average daily quantity of marijuana smoked and decrease in sGaw.

Long-term Marijuana Smoking and Changes in Pulmonary Function

Fourteen studies (Table 2) addressed the impact of long-term marijuana smoking (described as nontobacco cigarette smoking in 2 studies18,24) on abnormalities in pulmonary function, including 10 cross-sectional studies,† 3 observational cohort studies,24,26,29 and 1 case series.20

Table 2.

Studies That Reported Effects of Long-term Marijuana Inhalation on Pulmonary Function

| Source | Study Design | No. of Subjects |

Results | Control for Confounding |

Mean Generic Quality Score |

Mean Exposure and Disease Specific Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloom et al,18 1987 | Cross-sectional | 990 | For spirometric data: no significant effect of nontobacco cigarette smoking on FEV1 or FVC. Current smokers of nontobacco cigarettes showed significant decreases in FEV1/FVC ratio at P<.05 compared with | Tobacco | 14 | 3 |

| Cruickshank,19 1976 | Cross-sectional | 60 | No differences in pulmonary function between marijuana smokers and controls | None | 6.5 | 1.5 |

| Henderson et al,20 1972 | Case series | 200 | Among patients presenting with complaints consistent with chronic bronchitis, vital capacity reduced 15%–40% | None | 4.5 | 1 |

| Hernandez et al,21 1981 | Cross-sectional | 23 | Spirometry results normal in marijuana users | None | 9.5 | 3 |

| Moore et al,22 2005 | Cross-sectional | 6728 | Compared with nonusers, marijuana and tobacco users had higher proportion of subjects with an FEV1/FVC ratio <70% predicted (OR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.54–4.35; and OR, 6.25; 95% CI, 4.76–8.33, respectively). Controlling for tobacco, marijuana use was not associated with a decreased FEV1/FVC ratio. | Tobacco | 17.5 | 3 |

| Sherman et al,23 1991 | Cross-sectional | 63 | No significant difference in FEV1/FVC and DLCO in marijuana smokers compared with nonsmokers | Tobacco | 10 | 3 |

| Sherrill et al,24 1991 | Observational cohort | 856 | Indexes of pulmonary function were significantly reduced in subjects reporting nontobacco cigarette smoking longitudinally | Tobacco | 13.5 | 3 |

| Tashkin et al,25 1980 | Cross-sectional | 189 | Marijuana smokers had lower sGaw compared with controls (P<.001) | Tobacco | 8.5 | 2.5 |

| Tashkin et al,26 1997 | Observational cohort | 394 | No effect of long-term marijuana smoking on FEV1 decline | Tobacco | 12 | 3 |

| Tashkin et al,27 1993 | Cross-sectional | 542 | Association between marijuana smoking and decline of FEV1 in response to low doses of methacholine, indicating airway hyperresponsiveness | Tobacco | 10.5 | 3 |

| Taylor et al,28 2000 | Cross-sectional | 862 | Greater proportion of marijuana-dependent individuals showed a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio compared with nonsmokers (P<.007) | Tobacco | 12.5 | 3 |

| Taylor et al,29 2002 | Observational cohort | 930 | Linear relationship between number of times cannabis used and decreasing FEV1/FVC (P<.05). However, once confounders of age tobacco, and weight were adjusted for, relationship was no longer significant (P = .09). | Tobacco | 13.5 | 3 |

| Tilles et al,30 1986 | Cross-sectional | 68 | Marijuana smoking, with or without tobacco smoking, was associated with a reduction in single-breath DLCO compared with nonsmoking controls (P<.05) | Tobacco | 10.5 | 2.5 |

| Tashkin et al,31 1987 | Cross-sectional | 446 | Male marijuana smokers had reduced sGaw compared with male tobacco smokers. No difference in DLCO among marijuana smokers and nonsmokers. | Tobacco | 12 | 3 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; OR, odds ratio; sGaw, specific airway conductance.

Of these, 9 studies18–20,22–24,26,28,29 reported data on the effect of marijuana smoking on FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC. One observational cohort study26 reported no change in FEV1 among marijuana smokers for a mean ± SD follow-up of 4.9±2.0 years. Another observational cohort study24 showed a 142-mL decrease in FEV1 among patients who had previously smoked nontobacco cigarettes (P<.01). One case series20 noted that long-term hashish smokers who presented with respiratory complaints had a 15% to 40% decreased FVC compared with controls. One large cross-sectional study18 showed that male nontobacco cigarette smokers had a decrease in FEV1/FVC ratio compared with both nonsmokers (90% predicted vs 98.4% predicted; P<.05) and tobacco smokers (90% predicted vs 95.2% predicted; P<.05). Two other cross-sectional studies22,28 reported a decrease in the FEV1/FVC ratio among marijuana smokers when compared with nonsmokers, but after adjusting for tobacco use, 1 of these studies22 demonstrated no difference between marijuana smokers and nonsmokers. One observational cohort study24 reported that FEV1/FVC was reduced 1 year or more after nontobacco cigarette smoking compared with nonsmoking (decreased 1.9%±0.7%; P<.01), but no dose-response relationship was noted. Another large observational cohort study,29 which followed up a birth cohort into adolescence, found that individuals using cannabis more than 900 times had mean FEV1/FVC values that were decreased 7.2% at the age of 18 years, 2.5% at the age of 21 years, and 5.0% at the age of 26 years compared with nonsmokers (P<.05 for all comparisons), but when adjusted for age, tobacco smoking, and weight, the association was no longer statistically significant. Two cross-sectional studies19,23 reported no differences with respect to FEV1/FVC ratio.

Three studies23,30,31 examined changes in the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) with long-term marijuana use. The DLCO was reduced in long-term marijuana smokers (74%±20% predicted) compared with nonsmoking controls (92%±11% predicted; P<.05) in 1 cross-sectional study,30 although 2 studies22,31 reported no difference in DLCO between long-term marijuana smokers and nonsmokers.

Four studies21,25,27,31 examined the impact of long-term marijuana smoking on airway resistance and airway hyperresponsiveness. Long-term marijuana smoking was associated with a decrease in sGaw in 2 cross-sectional studies; one25 showed a decrease compared with control subjects (0.17±0.00 L/s per centimeter H2O for marijuana smokers and 0.24±0.01 L/s per centimeter H2O for controls; P<.001), and the other31 showed that, among men only, sGaw was decreased in marijuana smokers compared with tobacco smokers (0.19 L/s per centimeter H2O for marijuana smokers and 0.21 L/s per centimeter H2O for tobacco smokers; P<.03). Another cross-sectional study21 reported no change in airway resistance in response to inhaled histamine in marijuana users compared with nonsmoking controls. Finally, another cross-sectional study27 reported an association between long-term marijuana smoking and a decrease in FEV1 to lower doses of methacholine compared with nonsmoking controls, suggesting nonspecific airway hyperresponsiveness.

Long-term Marijuana Smoking and Respiratory Complications

We reviewed 14 studies (Table 3) that assessed the impact of long-term marijuana smoking on respiratory complications; 9 were cross-sectional, 18,22,28,31,34–38 3 were case series,20,33,39 1 was a case-control study,32 and 1 was an observational cohort.24 All 14 studies showed an association between marijuana smoking (or nontobacco cigarette smoking) and an increased risk of various respiratory complications.

Table 3.

Studies That Reported Effects of Long-term Marijuana Inhalation on Respiratory Complications

| Source | Study Design | No of Subjects |

Results | Control for Confounding |

Mean Generic Quality Score |

Mean Exposure and Disease Specific Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloom et al,18 1987 | Cross-sectional | 990 | Multivariable analysis shows association between intensity and duration of nontobacco cigarettes and cough, phlegm, and wheeze | Tobacco | 14 | 3 |

| Henderson et al,20 1972 | Case series | 200 | Cannabis smokers complained of pharyngitis (n = 150), rhinitis (n = 26), chronic bronchitis (n = 20), and asthma (n = 4) | None | 4.5 | 0.5 |

| Moore et al,22 2005 | Cross-sectional | 6728 | Marijuana use associated with respiratory symptoms, chronic bronchitis, coughing on most days, phlegm, wheezing, and chest sounds without a cold | Tobacco | 17.5 | 3 |

| Sherrill et al,24 1991 | Observational cohort | 1802 | Marijuana smoking associated with cough, phlegm, and wheeze | Tobacco | 13.5 | 3 |

| Taylor et al,28 2000 | Cross-sectional | 943 | Marijuana use associated with wheezing apart from colds, exercise-related shortness of breath, nocturnal waking with chest tightness, and morning sputum production | Tobacco | 12.5 | 3 |

| Tashkin et al,31 1987 | Cross-sectional | 446 | Marijuana smokers had increased rates of chronic cough, sputum production, wheeze, and more than 1 prolonged episode of bronchitis during the previous 3 y compared with the nonsmokers | Tobacco | 11.5 | 3 |

| Gaeta et al,32 1996 | Case-control | 200 | 44% of asthma group compared with 20% of control group admitted to or tested positive for recent substance use (OR, 3.14; P<.001). In acute bronchospasm group, 82% admitted to recently using inhaled substances compared with 55% of controls (OR, 3.68; P<.02). No difference in proportions of asthma and control groups that reported marijuana use. | None | 12 | 1 |

| Tennant,33 1980 | Case series | 36 | Marijuana smokers complained of increased amounts of dyspnea and excess sputum production | None | 7 | 2 |

| Boulougouris et al,34 1976 | Cross-sectional | 82 | Verbal hoarseness was detected in 4 of 44 hashish users and 2 of 38 controls. Two of 44 users and 1 of 38 controls had signs of emphysema. | None | 8 | 1.5 |

| Chopra,35 1973 | Cross-sectional | 124 | Laryngitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, dyspnea, asthma, irritating cough, hoarse voice, and dryness of the throat were more common in those who smoked higher daily dose of marijuana. | None | 3 | 1 |

| Mehndiratta and Wig,36 1975 | Cross-sectional | 75 | Cannabis smokers complained of weight loss, cough, dyspnea, and poor sleep | None | 8 | 1.5 |

| Polen et al,37 1993 | Cross-sectional | 902 | Marijuana smokers reported more days ill with cold, flu, or sore throat in past year than nonsmokers | Tobacco | 15 | 3 |

| Stern et al,38 1987 | Cross-sectional | 173 | In patients with cystic fibrosis, 20% of marijuana users noted immediate and 5% noted long-term improvement in symptoms; 30% of users noted immediate and 40% noted long-term worsening of symptoms. | None | 13 | 1 |

| Tennant and Prendergast,39 1971 | Case series | 31 | 39% of marijuana smokers complained of rhinopharyngitis and 29% complained of bronchitis | None | 4 | 0.5 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Increased cough, sputum production, and wheeze were reported in 4 of these studies.18,22,24,31 One cross-sectional study31 reported increased prevalence of chronic cough (18%–24%), sputum production (20%–26%), and wheeze (25%–37%) among marijuana and/or tobacco smokers compared with nonsmokers (P<.05 for all comparisons) but not between marijuana and tobacco smokers. A large cross-sectional study18 suggested a dose response between intensity and duration of nontobacco cigarette smoking and cough. Another large cross-sectional study22 showed that after controlling for sex, age, current asthma, and number of tobacco cigarettes smoked per day, marijuana smoking was associated with increased odds of cough (odds ratio [OR], 2.00; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.32–3.01), phlegm (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.35–2.66), and wheeze (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.05–4.34) compared with controls (P<.01 for all comparisons). A large observational cohort study24 showed an increased odds of cough (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.21–2.47), phlegm (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.08–2.18), and wheeze (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.50–2.70) in current nontobacco smokers compared with nonsmokers after adjusting for age, tobacco smoking, and occurrence of symptoms reported previously.

The remainder of the studies showed an association between marijuana smoking and various respiratory complications: bronchitis, 20,22,31,35,39 dyspnea,28,33,35,36 pharyngitis, 20,35,37 hoarse voice,34,35 worsening asthma symptoms,20,35 abnormal chest sounds,22 worsening cystic fibrosis symptoms,38 acute exacerbations of bronchial asthma,32 and chest tightness.28

STUDY QUALITY

On the basis of study design, the studies reported were of variable quality using the standardized scale.5 The mean quality score was 12.6 (range, 6–18) for the 12 challenge studies, 5.2 (range, 4–7) for the 3 case series, 10.5 (range, 3–19) for the 15 cross-sectional studies, 12 for the 1 case-control study, and 13 (range, 10–14) for the 3 observational cohort studies.

Study quality was also evaluated based on study outcome. The mean quality score for the airway response in studies of short-term marijuana use was 12.6 (range, 6–18). For studies that evaluated changes in pulmonary function secondary to long-term marijuana smoking, the mean quality score was 11.1 (range, 4–19). For the studies categorized as respiratory complications secondary to long-term marijuana smoking, the mean quality score was 10.3 (range, 4–18).

When also scoring publications based on disease-specific criteria, the studies that met the highest level of study quality using both scales were the 3 observational cohort studies. 24,26,29 Therefore, a discussion of these 3 studies in greater detail is warranted. The most recent observational cohort study29 followed up a birth cohort of 930 participants in New Zealand to the age of 26 years. At 18, 21, and 26 years of age, marijuana and tobacco smoking were assessed with a standardized questionnaire, and pulmonary function was measured by spirometry. Confounding factors (age, tobacco smoking measured as cigarettes per day, and weight) were accounted for using a fixed-effects regression model. The authors report that during 8 years of follow-up, the dose-dependent relationship seen between cumulative marijuana smoking and decreasing FEV1/FVC was reduced to nonsignificant once the confounding factors were controlled for. The authors suggest that longer follow-up time is necessary for the dose-dependent relationship to persist in the context of confounding factors.

Another observational cohort study26 followed up a convenience sample of 394 white adults for 8 years. Among the study participants, 131 were heavy and habitual smokers of marijuana, 112 smoked marijuana and tobacco, 65 smoked only tobacco, and 86 were nonsmokers; 255 participants had measurement of FEV1 at least 6 times during an 8-year period. A random-effects model, including height, intensity of marijuana use (marijuana cigarettes per day), and intensity of tobacco use (cigarettes per day) was used and failed to show a significant relationship between marijuana smoking and FEV1 decline. Potential weaknesses of this study include lack of adjustment of duration of marijuana smoking and a low follow-up rate of 65%.

An additional observational cohort study24 used data obtained from 3-year follow-up surveys conducted during a 6-year period in a random stratified cluster sample of households in Tucson, Ariz, between 1981 and 1988. Using a 2-stage random-effects model with height and sex as constant covariates and nontobacco cigarette smoking and tobacco cigarette smoking (and their interactions) as time-dependent covariates, the authors showed that among 856 subjects for whom longitudinal pulmonary function data were available, nontobacco cigarette smokers had a significant decrease in FEV1/FVC ratio and previous nontobacco smokers had a decrease in FEV1. Of the total study population (n=1802), current nontobacco cigarette smokers had an increase in chronic cough, phlegm, and wheeze after adjusting for age, tobacco smoking, and preexisting symptoms (from a prior assessment). The potential limitations of this study include the author’s focus on subjects who smoked nontobacco cigarettes (which were assumed to contain marijuana), a relatively low number of respondents with current nontobacco cigarette smoking (range, 57–79 respondents), and different questions used to assess current nontobacco cigarette smoking in earlier surveys compared with later surveys.

COMMENT

We systematically reviewed 34 studies that assessed the impact of short-term marijuana use on airway response and long-term marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications. This literature supports a bronchodilating effect soon after marijuana inhalation, although the results of 1 study suggested a reversal of this effect after more prolonged marijuana smoking. Overall, these studies fail to report a consistent association between long-term marijuana smoking and FEV1/FVC ratio, DLCO, or airway hyperreactivity. Finally, the literature suggests that long-term marijuana smoking is associated with an increased risk of respiratory complications, including an increase in cough, sputum production, and wheeze, persisting after adjusting for tobacco smoking.

This research may inform the debate regarding the increasing use of marijuana for medical purposes accompanying recent legislative changes.40Our findings, however, do not directly apply to pulmonary administration of tetrahydrocannabinol via specialized delivery systems.41

Our synthesis of the data is unique compared with other reviews in the literature. A recent review4 reported that marijuana smoking was associated with airway inflammation, acute bronchospasm, airflow obstruction, diffusion impairment, and emphysema. Another recent review3 noted an association between bronchodilation and increased cough, sputum, and airway inflammation with long-term marijuana smoking. Our systematic review covers a broader range of studies than previously included and also considers study quality.

The studies we reviewed were variable in quality when evaluated with a standardized assessment tool and a disease-specific assessment tool. Therefore, many methodological limitations need to be considered when interpreting the data reviewed herein. For example, many of the studies failed to adjust for important confounding factors, including tobacco, other inhaled drugs, and occupational and environmental exposures. Although some studies controlled for tobacco smoking status (ie, past, present, or never smoking), most, including the 3 observational cohort studies, did not control for dose or duration (ie, pack-years) of tobacco use, the best available measure of tobacco exposure, which is most strongly correlated with the development of obstructive lung disease. In addition, among the studies that examined the effect of long-term marijuana smoking on respiratory complications and pulmonary function, no standardized measure of marijuana dose or duration was defined. Although some studies reported marijuana cigarette–years of marijuana exposure, other studies reported only if the number of times marijuana was used by an individual was greater than a certain threshold, which varied from at least once to more than 900 times. Also, outcome measurements were not standardized. These factors pose difficulties in comparing and/or combining the results of studies. Finally, our search strategies, although extensive, may not have identified all possible studies that examined these relationships.

Despite these limitations, this review should alert primary care physicians to the potential adverse health outcomes associated with the widespread use and abuse of and dependence on marijuana. Large prospective studies should be designed that carefully account for potential confounding factors (including detailed assessments of tobacco, substance abuse, and occupational and environmental exposures) that can affect lung health. Such studies should use standard exposure and outcome criteria to accurately measure potential associations. The present findings should be considered in conjunction with a recent review42 that showed an association between marijuana smoking and premalignant changes in the lung. On the basis of currently available information, health care professionals should consider marijuana smoking in their patients who present with respiratory complications and advise their patients regarding the potential impact of this behavior on their health.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the Program of Research Integrating Substance Use in Mainstream Healthcare (PRISM) with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The codirectors of PRISM are A. T. McLellan, PhD, of the Treatment Research Institute and B. J. Turner, MD, MSEd, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Dr Tetrault is supported by the Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations. Dr Crothers is supported by the Yale Mentored Clinical Scholar Program (grant NIH/NCRR K12 RR0117594-01). Dr Moore is supported by NIDA grant R21 DA019246-02. Dr Mehra is supported by an American Heart Association award (grant 0530188N), an Association of Subspecialty Professors and CHEST Foundation of the American College of Chest Physicians T. Franklin Williams Geriatric Development Research Award, and a K23 Mentored Patient- Oriented Career Development Award (NIH/NHLBI HL079114). Dr Fiellin is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Statistics. [Accessed November 9, 2005];Data from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2006 http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH.htm.

- 2.Cottler LB, Helzer JE, Mager D, Spitznagel EL, Compton WM. Agreement between DSM-III and III-R substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1991;29:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(91)90018-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tashkin DP. Smoked marijuana as a cause of lung injury. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005;63:93–100. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2005.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolff AJ, O’Donnell AE. Pulmonary effects of illicit drug use. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:203–216. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(03)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1988;52:377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vachon L, Sulkowski A, Rich E. Marihuana effects on learning, attention and time estimation. Psychopharmacologia. 1974;39:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00421453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tashkin DP, Shapiro BJ, Frank IM. Acute effects of smoked marijuana and oral delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on specific airway conductance in asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;109:420–428. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.109.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein JG, Kuehnle JC, Mendelson JH. Medical implications of marijuana use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1976;3:347–361. doi: 10.3109/00952997609077203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laviolette M, Belanger J. Role of prostaglandins in marihuana-induced bronchodilation. Respiration. 1986;49:10–15. doi: 10.1159/000194853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renaud AM, Cormier Y. Acute effects of marihuana smoking on maximal exercise performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1986;18:685–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steadward RD, Singh M. The effects of smoking marihuana on physical performance. Med Sci Sports. 1975;7:309–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tashkin DP, Shapiro BJ, Frank IM. Acute pulmonary physiologic effects of smoked marijuana and oral 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy young men. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:336–341. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197308162890702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tashkin DP, Shapiro BJ, Lee YE, Harper CE. Effects of smoked marijuana in experimentally induced asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975;112:377–386. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.112.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tashkin DP, Shapiro BJ, Lee YE, Harper CE. Subacute effects of heavy marihuana smoking on pulmonary function in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:125–129. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197601152940302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tashkin DP, Reiss S, Shapiro BJ, Calvarese B, Olsen JL, Lodge JW. Bronchial effects of aerosolized delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy and asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115:57–65. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vachon L, FitzGerald MX, Solliday NH, Gould IA, Gaensler EA. Single-dose effects of marihuana smoke. Bronchial dynamics and respiratory-center sensitivity in normal subjects. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:985–989. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197305102881902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu HD, Wright RS, Sassoon CS, Tashkin DP. Effects of smoked marijuana of varying potency on ventilatory drive and metabolic rate. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:716–721. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloom JW, Kaltenborn WT, Paoletti P, Camilli A, Lebowitz MD. Respiratory effects of nontobacco cigarettes. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:1516–1518. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6612.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruickshank EK. Physical assessment of 30 chronic cannabis users and 30 matched controls. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;282:162–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb49895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson RL, Tennant FS, Guerry R. Respiratory manifestations of hashish smoking. Arch Otolaryngol. 1972;95:248–251. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1972.00770080390012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez MJ, Martinez F, Blair HT, Miller WC. Airway response to inhaled histamine in asymptomatic long-term marijuana smokers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981;67:153–155. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(81)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore BA, Augustson EM, Moser RP, Budney AJ. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a US sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:33–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman MP, Roth MD, Gong H, Jr, Tashkin DP. Marijuana smoking, pulmonary function, and lung macrophage oxidant release. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:663–669. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90379-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherrill DL, Krzyzanowski M, Bloom JW, Lebowitz MD. Respiratory effects of non-tobacco cigarettes: a longitudinal study in general population. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:132–137. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tashkin DP, Calvarese BM, Simmons MS, Shapiro BJ. Respiratory status of seventy-four habitual marijuana smokers. Chest. 1980;78:699–706. doi: 10.1378/chest.78.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tashkin DP, Simmons MS, Sherrill DL, Coulson AH. Heavy habitual marijuana smoking does not cause an accelerated decline in FEV1 with age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:141–148. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tashkin DP, Simmons MS, Chang P, Liu H, Coulson AH. Effects of smoked substance abuse on nonspecific airway hyperresponsiveness. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:97–103. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor DR, Poulton R, Moffitt TE, Ramankutty P, Sears MR. The respiratory effects of cannabis dependence in young adults. Addiction. 2000;95:1669–1677. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor DR, Fergusson DM, Milne BJ, et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of tobacco and cannabis exposure on lung function in young adults. Addiction. 2002;97:1055–1061. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tilles DS, Goldenheim PD, Johnson DC, Mendelson JH, Mello NK, Hales CA. Marijuana smoking as cause of reduction in single-breath carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. Am J Med. 1986;80:601–606. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90814-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tashkin DP, Coulson AH, Clark VA, et al. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in habitual heavy smokers of marijuana alone, smokers of marijuana and tobacco, smokers of tobacco alone, and nonsmokers. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:209–216. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaeta TJ, Hammock R, Spevack TA, Brown H, Rhoden K. Association between substance abuse and acute exacerbation of bronchial asthma. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:1170–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tennant FS., Jr Histopathologic and clinical abnormalities of the respiratory system in chronic hashish smokers. Subst Alcohol Actions Misuse. 1980;1:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulougouris JC, Panayiotopoulos CP, Antypas E, Liakos A, Stefanis C. Effects of chronic hashish use on medical status in 44 users compared with 38 controls. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;282:168–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb49896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chopra GS. Studies on psycho-clinical aspects of long-term marihuana use in 124 cases. Int J Addict. 1973;8:1015–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826087309033103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehndiratta SS, Wig NN. Psychosocial effects of longterm cannabis use in India. A study of fifty heavy users and controls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1975;1:71–81. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(75)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polen MR, Sidney S, Tekawa IS, Sadler M, Friedman GD. Health care use by frequent marijuana smokers who do not smoke tobacco. West J Med. 1993;158:596–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stern RC, Byard PJ, Tomashefski JF, Jr, Doershuk CF. Recreational use of psychoactive drugs by patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1987;111:293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tennant FS, Jr, Prendergast TJ. Medical manifestations associated with hashish. JAMA. 1971;216:1965–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kane B. Medical marijuana: the continuing story. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1159–1162. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hazekamp A, Ruhaak R, Zuurman L, van Gerven J, Verpoorte R. Evaluation of a vaporizing device (Volcano) for the pulmonary administration of tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:1308–1317. doi: 10.1002/jps.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehra R, Moore BA, Crothers K, Tetrault J, Fiellin DA. The association between marijuana smoking and lung cancer: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]