Abstract

Interprofessional education (IPE) is an important step in advancing health professional education for many years and has been endorsed by the Institute of Medicine as a mechanism to improve the overall quality of health care. IPE has also become an area of focus for the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), with several groups, including these authors from the AACP Interprofessional Education Task Force, working on developing resources to promote and support IPE planning and development. This review provides background on the definition of IPE, evidence to support IPE, the need for IPE, student competencies and objectives for IPE, barriers to implementation of IPE, and elements critical for successfully implementing IPE.

Keywords: interprofessional education, competencies

INTRODUCTION

Interprofessional education is an important pedagogical approach for preparing health professions students to provide patient care in a collaborative team environment. The appealing premise of IPE is that once health care professionals begin to work together in a collaborative manner, patient care will improve.1-4 Interprofessional teams enhance the quality of patient care, lower costs, decrease patients' length of stay, and reduce medical errors.5 The World Health Organization,6 National Academies of Practice2, and the American Public Health Association7 are a few of the many organizations that have articulated support of IPE.5,8-10 Most notably, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) declared that “health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team…”.5 The IOM has clearly stated that patients received safer, high quality care when health care professionals worked effectively in a team, communicated productively, and understood each other's roles.5 Although there is an abundance of evidence supporting the IPE of health professions students,11-19 this is not the norm in most schools and colleges of pharmacy. This review of IPE presents definitions, provides supporting evidence, outlines the need, proposes student competencies and objectives, summarizes the barriers to implementation, and defines elements critical for successful implementation.

In 2005, the AACP Strategic Planning Committee met for a full day to discuss the issues and needs of AACP members with respect to IPE. The group reviewed current projects, identified opportunities for committee investigation, discussed the need for diverse models of IPE, and discussed opportunities for AACP program development.20 The 2006-2007 Professional Affairs Committee Report stated they “accept the premise that team-delivered care results in better health outcomes. The Committee therefore recommends that AACP endorse the competencies of the IOM for health professions education and advocates that all schools and colleges of pharmacy provide faculty and students meaningful opportunities to engage in IPE, practice and research to better meet health needs of society.”21 Also in 2006-2007, the Academic Affairs Committee suggested in their report that schools and colleges of pharmacy “support and enhance IPE including interprofessional preceptor development.”22 In 2007 at the AACP Annual Meeting, the AACP Section of Teachers of Pharmacy Practice recommended the Association “develop resources to assist faculty in promoting their IPE course and experiences at their schools and colleges.”23 Thus, AACP and many of its constituents have indicated that IPE is a priority in pharmacy education.

In 2005-2006, AACP convened a Council of Faculties Interprofessional Education Task Force with the charge of defining IPE, developing competencies in IPE, and identifying issues in implementing IPE in the various types of schools and colleges of pharmacy. This work was continued with the 2006-2007 Task Force identifying common curricular themes for IPE and how to implement IPE in each of the varied types of schools and colleges environments. The 2007-2008 Task Force focused on identifying faculty development resources useful in promoting competency in IPE, recommending means of implementing IPE and disseminating findings in a scholarly manner.

DEFINITION OF INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

Before engaging in the development and implementation of IPE at any institution, it is important to define the elements of IPE. Definitions of IPE are varied and ubiquitous.8 The Task Force expanded the Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) definition to read as follows:

Interprofessional education involves educators and learners from 2 or more health professions and their foundational disciplines who jointly create and foster a collaborative learning environment. The goal of these efforts is to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes that result in interprofessional team behaviors and competence. Ideally, interprofessional education is incorporated throughout the entire curriculum in a vertically and horizontally integrated fashion.5,8,24

It is important to also consider what is not IPE. Examples of what IPE is not include:

Students from different health professions in a classroom receiving the same learning experience without reflective interaction among students from the various professions3;

A faculty member from a different profession leading a classroom learning experience without relating how the professions would interact in an interprofessional manner of care; and

Participating in a patient care setting led by an individual from another profession without sharing of decision-making or responsibility for patient care.5,8,24

The goal of IPE is for students to learn how to function in an interprofessional team and carry this knowledge, skill, and value into their future practice, ultimately providing interprofessional patient care as part of a collaborative team and focused on improving patient outcomes. An interprofessional team is composed of members from different health professions who have specialized knowledge, skills, and abilities.5 The goal of an interprofessional team is to provide patient-centered care in a collaborative manner. The team establishes a common goal and using their individual expertise, works in concert to achieve that patient-centered goal.24 Team members synthesize their observations and profession-specific expertise to collaborate and communicate as a team for optimal patient care.5 In this model, joint decision making is valued and each team member is empowered to assume leadership on patient care issues appropriate to their expertise.24 Health care professionals from different disciplines who conduct individual assessments of a patient and independently develop a treatment plans are not considered an interprofessional team. In this traditional model, the physician typically orders the services and coordinates the care and the lack of collaboration may contribute to an overlap and conflict in care.24

EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT IPE

Although an initial Cochrane review in 2000 found no studies which met inclusion criteria,25 a review in 2008 identified 6 studies evaluating the effectiveness of IPE compared with traditional education on patient care outcomes and professional practice. Four of the studies showed positive outcomes on patient satisfaction, teamwork, error rates, mental health competencies or care delivered to domestic violence victims, while the other 2 found no impact on patient care or practice. Since there were a small number of studies with different interventions, general conclusions could not be drawn. However, based on an interpretative approach to synthesizing the data, one can summarize that they were well received by participants, enabled students and practitioners to learn the knowledge and skills necessary for collaborative working, and can improve the delivery of services and make a positive impact on care.26 Another review article in 2007 included 21 articles evaluating IPE; again, there were differences in the methodologies and outcomes of each study, and the results were provided in narrative manner. These studies illustrated positive reactions from learners, a positive change in perceptions and attitudes, and a positive change in knowledge and skills necessary for collaboration. Key mechanisms for effective IPE include principles of adult learning and staff development to improve group facilitation.27

A systematic review by pharmacy educators investigated the evidence of educational interventions in health professions to enhance learner outcomes related to interprofessional care. Upon review of 13 IPE training programs, positive results were seen in the knowledge domain when tested on other professions' roles and skills, interprofessional care, geriatrics, and quality improvement methods. Learners demonstrated positive results when measured on attitude toward other professions and health care teams. This review found minimal evidence for persistent behavior change related to group interactions, problem solving, and communications skills.28 The authors suggested that more controlled trials with objective outcome criteria are necessary.

Evolution of Interprofessional Education

The need for IPE has been recognized internationally since the mid 1980s. In the United Kingdom, the Center for the Advancement of Interprofessional Professional Education (CAIPE) 8 was established in 1987, and The Journal for Interprofessional Care was first published in 1986. In Canada, the Interprofessional Education for Collaborative Patient-Centered Practice Initiative was begun by Health Canada in 2003.29

Traditionally, individual health professions have been trained primarily in their own schools or colleges by members of the same profession. Traditionally, first- through third-year pharmacy students have been taught in classrooms only with other pharmacy students. For many students, their first exposure to IPE does not occur until they reach their advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) in the fourth year. There are exceptions in specific institutions or specific cases where IPE has been integrated earlier into the curriculum,17,30-32 but this is not yet the standard in pharmacy education.

In 2007, faculty members from the St. Louis College of Pharmacy conducted a survey of schools and colleges of pharmacy regarding IPE. Of the 31 schools responding to the survey, 47% were not currently offering IPE. Information on interprofessional offerings at the schools not responding are unknown, but their lack of response may indicate an even higher percentage of total programs not offering IPE. Of the schools and colleges offering IPE, the authors found that more than 60% of the interprofessional courses were offered in the third or fourth year of the PharmD program, with only 25% of schools offering these courses in the first year.33

Interprofessional education is, indeed, evolving slowing. Five years after the challenge from the IOM report, there has been minimal significant change in health professions education specifically designed to address the issue of IPE. However, there has been increased involvement from the health care community in this direction. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement Health Professions Education Collaborative was established to create exemplary learning and care models that promote the improvement of health care through both profession-specific and interprofessional learning experiences.34 In addition, there are a growing number of opportunities in interprofessional education conferences, such as the All Together Better Health Conferences, which are held biannually in locations around the world.35

NEED FOR INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

In addition to the evidence supporting the value of IPE, various factors have contributed to the need for IPE. These include a recent IOM report as well as accreditation standards and guidelines from several health care professions.

The 2003 IOM report “Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality” reflected discussion from an interprofessional summit held the prior year involving 150 participants across many health care professions. The resulting 5 core competencies that should be common in health professions' education were imbedded in the following vision statement from the summit: “All health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interprofessional team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics.”5 This report has served as a major impetus for health care professional and educational organizations to move forward in meeting the need for IPE.

Accreditation standards and guidelines from health care professions have also addressed the necessity for this collaborative approach in education. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) created standards and guidelines effective since July 2007 that delineate the desire for IPE. Guidelines 1.4, 6.2, 9.1, and several areas in Standard 12 clearly engage interprofessional learning, practice, activities, and patient care. Specifically, Guideline 1.4 asserts that “the college or school's values should include a stated commitment to a culture that, in general, respects and promotes development of interprofessional learning and collaborative practice”; Guideline 6.2 states that “the relationships, collaborations, and partnerships collectively should promote integrated and synergistic interprofessional and interdisciplinary activities”; and Guideline 9.1 affirms that “the college or school must ensure that the curriculum addresses…competencies needed to work as a member of or on an interprofessional team.”36

Concerning medical education, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) is the accrediting body for medical schools in the United States and Canada. Currently, there are no official accreditation standards about IPE specifically in medical education. However, Standards ED-19 and ED-23 refer to interacting with other health care providers and state that “there must be specific instruction in communication skills as they relate to physician responsibilities, including communication with patients, families, colleagues, and other health professionals. A medical school must teach medical ethics and human values, and require its students to exhibit scrupulous ethical principles in caring for patients, and in relating to patients' families and to others involved in patient care.”37

The Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education is the accrediting agency for baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs in the United States and works closely with the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice contains the accepted standards for baccalaureate programs in nursing and was recently revised in 2008. Essential VI (Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration for Improving Patient Health Outcomes) focuses on IPE as a central competency for patient-centered care. Part of the document states that “interprofessional education enables the baccalaureate graduate to enter the workplace with baseline competencies and confidence for interactions and communication skills, that will improve practice, thus yielding better patient outcomes…. interprofessional education optimizes opportunities for the development of respect and trust for other members of the health care team.”38 This standard also includes examples of integrative strategies for learning through IPE, such as course assignments, simulation laboratories, and community projects.

The Commission on Dental Accreditation has outlined standards for both general and advanced education programs in dentistry. General dentistry Standard 1-8 states that “the dental school must show evidence of interaction with other components of the higher education, health care education and/or health care delivery systems.”39 Additionally, even though the standards for advanced education programs in dentistry do not address IPE specifically, there is mention of interprofessional teamwork and interacting with other health care professionals: “the goals of these programs should include preparation of the graduate to function effectively and efficiently in multiple health care environments within interprofessional health care teams… including consultation and referral.”40

Lastly, the Association of Schools of Allied Health Professions chose for its 2006 Annual Conference the theme of “Framing Interprofessional Education, Practice, and Research: Preparing Allied Health Professionals for the 21st Century”.41 Although accreditation standards for each of the allied health professions will not be discussed individually at this juncture, it is intriguing to know that IPE is a major focus of this professional organization. As other health professions accrediting bodies move to include IPE in their standards, this will serve as an additional incentive for the profession to work together to overcome barriers in IPE.

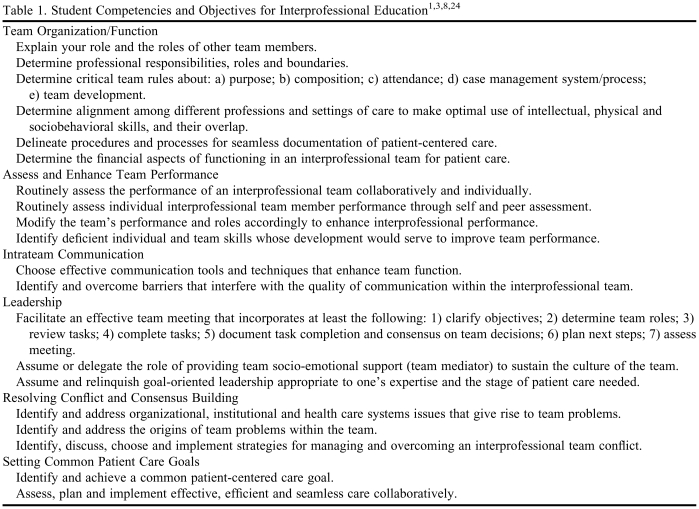

As mentioned earlier, the IOM report developed core competencies for health professions education including “work in interdisciplinary teams: cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable.”5 In conjunction with these core IOM competencies, the 2006-2007 Task Force developed student competencies achievable through IPE. Task Force members reviewed pertinent IPE literature,1,3,8,24 brainstormed potential competencies, and used a consensus approach to develop the final list of competencies. Each competency has specific objectives that help build toward the overarching competency. The Task Force recommends that these competencies be achieved through interprofessional education: team organization and function, assessing and enhancing team performance, intrateam communication, leadership, resolving conflict and consensus building, and setting common patient care goals.

Many of the competencies proposed for IPE relate to teamwork. Sharing information about the roles of team members, determining professional responsibilities and boundaries, and learning about how different professions can work together to optimize their strengths in providing patient care all contribute to the development of professionals working together towards a common goal (eg, optimizing patient care). Communication is a key skill in effective team functioning; the ability to use communication techniques to enhance team functioning and deal with barriers that interfere with communication is necessary for optimal teamwork. Understanding how to assess team performance and use that data to improve team members' skills and modify roles to enhance performance is an important competency in IPE. Leadership can be an important competency for interprofessional education and learning how to effectively facilitate an interprofessional team meeting is one important objective. Objectives related to conflict resolution and consensus building are essential to building an effective interprofessional team player. Learning how to identify and address the origin of team problems and implement strategies for overcoming these issues are objectives that build toward competence in resolving conflict. Working together to set common patient care goals may be considered a terminal competency for interprofessional education. The ability to identify and achieve a common patient care goal as an interprofessional team of learners could be considered the ultimate goal for IPE. Table 1 includes a list of specific objectives within each competency area for IPE.1,3,8,24

Table 1.

BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTATION

Barriers to initiating IPE can be encountered at various levels of the organization including among the administration, faculty members, and students. A study of Canadian schools identified that the main barriers of IPE were scheduling, rigid curriculum, “turf battles,” and lack of perceived value to IPE.42 Attitudinal differences in health professionals, faculty members, and students also influence implementation of IPE. A lack of resources and commitment can negatively affect the implementation of IPE.43

Barriers at the administrative level are multifactorial, including the perception of whether it is worthwhile to direct resources to a new change given the demands of the other missions of an institution. It is important that administrators understand and facilitate the need for changing the education and training of professionals as health care changes. In addition, logistical concerns such as scheduling and space may need to be overcome at the administrative level to advance a longterm commitment to IPE. Faculty members will also need to appreciate the advantages of IPE so that they can be fully engaged in implementing the change. Faculty members may be resistant to changes due to increased workload and lack of time. Leaders in the professional field have a responsibility to motivate faculty members to make these changes and have a system to reward faculty members for their efforts in developing and implementing IPE. Operations management of the education system in many professions will need to be altered to align the curricula to one another. This includes the physical space as well as course design and scheduling. Ideally, the physical space of schools and colleges should be adaptable to IPE. This may require modification of current structures of schools, and IPE should be considered when new schools are being designed and built. Another barrier in implementation is the logistical challenge of synchronizing classes among different health professions so that students can physically be together to learn. It may be difficult to find common times for IPE courses and available classrooms large enough to accommodate the increased numbers of students. Also, even if a university has multiple health professions schools, they may not be in close proximity to one another. This may require allocating resources to develop multi-professional laboratories and classrooms for IPE.

The IOM report states that education should not occur in a vacuum, and a “hidden curriculum” exists. “This ‘hidden curriculum’ of observed faculty or clinician behavior, informal interactions and conversations with fellow students and with faculty and practicing professionals, and the overall norms and cultures of the training or practice environment is extremely powerful in shaping the values and attitudes of future health professionals.”5 The fact that many health care settings have not yet fully implemented interprofessional team care can be a barrier for IPE. Students may struggle with the application, or may not see the necessity of the team skills they learn during IPE. It is necessary to instill in students the importance of IPE to promote future change in the profession of pharmacy and in the overall health care system.

University environments differ considerably with respect to presence of different combinations of health professional schools within the universities or their surroundings. This will create another level of challenge. The design of a standardized curriculum for IPE that will include different professional schools is dependent on a variety of issues. IPE should be implemented in the basic, foundational courses.44 Developing these bridges between professions in basic courses may lay a foundation that will establish the tenets of interprofessional team care throughout the training period.

Assessing the outcome of IPE is particularly important give the resources committed to IPE. A systems approach for the centralized assessment of the health professional's outcome may become necessary. This will require all stakeholders to devise consistent evaluation tools and methods. Multidisciplinary development of the outcomes assessment process necessitates time and resource commitment from all of the health professions involved.

The process of implementing a new culture and cultural changes may indeed surprise the stakeholders with unknown barriers that were not anticipated during the original planning efforts. Professional organizations such as AACP, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP), American Pharmacists Association (APhA), American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists (ASHP), should work on a similar platform to overcome these barriers. A mutual collaboration of different health delivery professions will be needed to promote and implement IPE. All stakeholders, even in an individual profession and involved in education (as mentioned above) should come together for a better outcome of IPE.

ELEMENTS CRITICALTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF IPE

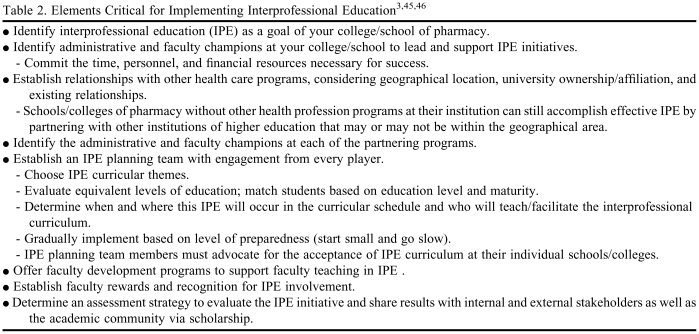

Regardless of the health care professions involved or location of the college or school, we purport that there are basic tenets of implementing IPE that, if followed, will help establish a successful IPE experience. The AACP Task Force on Interprofessional Education members used key IPE resources and professional experience with IPE to develop this list of steps essential in the process of IPE development. Personnel and financial resources as well as administrative and faculty time are essential for successful implementation of IPE. Thus, IPE should be identified as a goal of the curriculum or as part of the strategic plan. Those members of the faculty and administration who champion IPE need to lead and support IPE initiatives. It is necessary to cultivate relationships with other health care programs based on geographic location, existing relationships, etc. Administrative and faculty champions in the partnering programs need to be identified. Once an IPE planning team has been established, the team should identify appropriate IPE curricular themes and decide which students from each program should be involved based on equivalent levels of education. The team should determine when and where the IPE curriculum will occur and who will facilitate the curriculum. A gradual implementation of IPE with the motto “start small and go slow” is advocated so that some successes can be realized and modifications can be made with each iteration of the IPE curriculum. Development programs to support faculty teaching in IPE are encouraged as are recognition programs for faculty members involved in IPE. An assessment strategy to evaluate the IPE initiative should be planned, as well. Critical elements for implementing IPE are listed in Table 2.3,45,46

Table 2.

CONCLUSION

The definition of IPE as developed by the Task Force may serve as a guide to educators beginning the process of IPE development. There is considerable evidence to support IPE and certainly the accreditation standards for pharmacy may be considered one impetus. As with any educational curriculum, IPE ideally would foster specific competencies in the learner, including teamwork, leadership, consensus building, and the ability to identify and achieve common patient care goals. Although there are barriers to IPE, including logistical and resource issues, we advocate developing a plan for IPE that includes key elements critical for optimal success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thanks members of the AACP Interprofessional Education Task Force who contributed to the development of some information included in this article. Many thanks to Richard Herrier who was a member of the 2005-2006 AACP Task Force and chaired the 2006-2007 AACP Task Force. Special thanks to Tim Tracy who chaired the inaugural Task Force in 2005-2006 and Gayle Brazeau, Task Force member in 2007-2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth D. Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument, Assumption & Evidence. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brashers VL, Curry CE, Harper DC, et al. Interprofessional health care education: recommendations of the National Academies of Practice expert panel on health care in the 21st century. Issues in Interdisciplinary Care: National Academies of Practice Forum. 2001;3(1):21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeth D, Hammick M, Reeves S, Koppel I, Barr H. Effective Interprofessional Education: Development, Delivery & Evaluation. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4. TeamStepps: Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/index.htm. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 5.Institute of Medicine Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. In: Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Vol. 769. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1988. Learning Together to Work Together for Health. Report of a WHO study group on multiprofessional education for health personnel: the team approach. Technical Report Series; pp. 1–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Public Health Association. Policy statement on Promoting Interprofessional Education. http://www.apha.org/advocacy/policy/policysearch/default.htm?id=1374. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 8. Center for Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE). http://www.caipe.org.uk. Accessed April 17, 2008.

- 9. What is Interprofessional Education. Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC). http://www.cihc.ca/resources-files/CIHC_Factsheets_IPE_Feb09.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 10. European Interprofessional Education Network (EIPEN). http://www.eipen.org/. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 11.Andrus NC, Bennett NM. Developing an interdisciplinary, community-based education program for health professions students: the Rochester experience. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):326–331. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banks S, Janke K. Developing and implementing interprofessional learning in a faculty of health professions. J Allied Health. 1998;27(3):132–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett G, Greenwood R, Ross K. Integrating interprofessional education into 10 health and social care programmes. J Interprof Care. 2003;17(3):293–301. doi: 10.1080/1356182031000122915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilkey MB, Earp JA. Effective interdisciplinary training: lessons from the University of North Carolina's student health action coalition. Acad Med. 2006;81(8):749–58. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200608000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton CB, Smith CA, Butters JM. Interdisciplinary student health teams: combining medical education and service in a rural community-based experience. J Rural Health. 1997(4);13:320–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1997.tb00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hope JM, Lugassy D, Meyer R, Jeanty F, Myers S, Jones S, et al. Bringing interdisciplinary and multicultural team building to health care education: The downstate team-building initiative. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):74–83. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson AW, Potthoff SJ, Carranza L, et al. CLARION: A novel interprofessional approach to health care education. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):252–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn N, Davis A, Wilson M, et al. The interdisciplinary generalist curriculum (IGC) project: an overview of its experience and outcomes. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):S9–S12. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yarborough M, Jones T, Cyr TA, Phillips S, Stelzner D. Interprofessional education in ethics at an academic health sciences center. Acad Med. 2000;75(8):793–800. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Strategic Planning Committee Meeting Summary. September 13, 2005.

- 21.Kroboth P, Crismon LM, Daniels C, Hogue M, Reed L, Johnson L, et al. Getting to Solutions in Interprofessional Education: Report of the AACP 2006-2007 Professional Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6) Article S19. [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Curricula Then and Now: An Environmental Scan and Recommendations since the Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education. Report of the AACP 2006-2007 Academic Affairs Committee. July 2007. http://www.aacp.org/governance/COMMITTEES/academicaffairs/Documents/2006-07_AcadAffairs_Final%20Report.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 23. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Report of the Section of Teachers of Pharmacy Practice Resolutions Committee. July 2007. http://www.aacp.org/governance/SECTIONS/pharmacypractice/Documents/ResolutionsReport607.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 24. Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training Program. http://www.gittprogram.org. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 25. Zwarenstein M, Reeves S, Barr H, Hammick M, Koppel I, Atkins J. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD002213. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002213. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002213. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME Guide no. 9. Med Teach. 2007;29:735–51. doi: 10.1080/01421590701682576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remington TL, Foulk MA, Williams BC. Evaluation of evidence for interprofessional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4) doi: 10.5688/aj700366. Article 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Health Canada. Interprofessional Education for Collaborative Patient Centered Care. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/hhr-rhs/strateg/interprof/index_e.html. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 30.Borrego ME, Rhyne R, Hansbarger LC, et al. Pharmacy student participation in rural interdisciplinary education using problem based learning case tutorials. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(4):355–63. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salvatori P, Berry Su, Eva K. Implementation and evaluation of an interprofessional education initiative for students in the health professions. Learn Health Soc Care. 2007;6(2):72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westberg SM, Adams J, Thiede K, Bumgardner MA, Stratton T. An Interprofessional Activity Using Standardized Patients. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(2) doi: 10.5688/aj700234. Article 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grice G, Murphy J, Belgeri M, LaPlant B. Interprofessional education among schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3) Article 72 [meeting abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Health Professions Education Collaborative. Operations Plan 2007-2008. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/HealthProfessionsEducation/EducationGeneral/. Accessed February 15, 2008.

- 35. All Together Better Conference. http://www.alltogether.se/ Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 36. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree; 2006. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2000.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 37. Liaison Committee on Medical Education Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the M.D. Degree: Functions and Structure of a Medical School; 2007. http://www.lcme.org/functions2007jun.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 38. American Association of Colleges of Nursing Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice (2008). http://www.aacn.nche.edu/Education/pdf/BaccEssentials08.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 39. Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Programs; 2007. www.ada.org/prof/ed/accred/standards/predoc.pdf Accesed April 17, 2009.

- 40. Commission on Dental Accreditation, Accreditation Standards for Advanced Education Programs in General Dentistry; 2007. www.ada.org/prof/ed/accred/standards/aegd.pdf Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 41. Association of Schools of Allied Health Professions Newsletter; June 2006. www.asahp.org/trends/2006/June.pdf Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 42.Curran VR, Deacon DR, Fleet L. Academic administrators attitudes towards Interprofessional education in Canadian schools of health professional education. J Interprof Care. 2005;1:76–86. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardner SF, Chamberlin GD, Heestand DE, Stowe CD. Interdisciplinary didactic instruction at academic health centers in United States: Attitudes and barriers. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2002;7:179–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1021144215376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barr H, Ross F. Mainstreaming Interprofessional Education in United Kingdom: A position Paper. J Interprof Care. 2006:96–104. doi: 10.1080/13561820600649771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements for interprofessional education. Part 1: the learner, the educator and the learning context. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):21–38. doi: 10.1080/13561820500083550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements of interprofessional education. Part 2: factors, processes and outcomes. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):39–48. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]