Abstract

Although there is evidence to support implementing interprofessional education (IPE) in the health sciences, widespread implementation in health professions education is not yet a reality. Challenges include the diversity in location and settings of schools and colleges, ie, many are not located within an academic health center. Faculty members may not have the necessary skill set for teaching in an IPE environment. Certain topics or themes in a pharmacy curriculum may be more appropriate than others for teaching in an IPE setting. This paper offers solutions to teaching IPE in diverse settings, the construct for implementing a faculty development program for IPE, and suggested curricular topics with their associated learning objectives, potential teaching methods, and timelines for implementation.

Keywords: interprofessional education, faculty development, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

The fundamental premise of interprofessional education (IPE) asserts that if health professions students learn together at the beginning of and throughout their training they will be better prepared to deliver an integrated model of collaborative clinical care after entering practice. Accordingly, IPE has been identified as integral in the education of pharmacy students both by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy and the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. While there may be support by the profession to adopt IPE as an important pedagogy, certainly there are challenges and barriers to this effort. Before IPE can be initiated at any institution, a systematic planning, development, and implementation process should be outlined including a plan for faculty and curricular development. The goals of this review are twofold: (1) to provide pharmacy educators with a structural framework and building blocks for the development of IPE activities, and (2) to present the elements related to faculty development necessary for successful implementation of IPE activities.

The development and implementation of IPE experiences can present challenges including (1) the diversity of the mission and goals of the school or college, (2) the type of institution and settings where the school or college is located, and (3) the availability of other institutions and organizations outside the university where the school or college is located. The framework for the desired learning outcomes for the doctor of pharmacy degree are provided in the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Standards 2007.1 These standards may guide the development and implementation of IPE in the context of a school or college's unique academic environment.

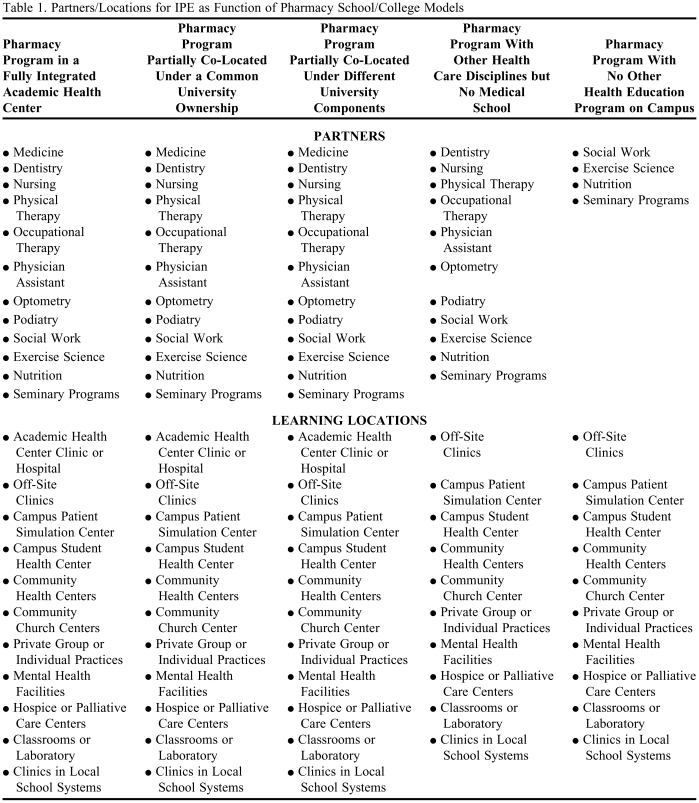

The first goal of this work was to differentiate and characterize the different educational environments where our schools/colleges are located. Five different models relevant to contemporary pharmacy education are proposed as frameworks to consider in the development and implementation of IPE activities. For example, only 31 of the current schools and colleges of pharmacy in the United States are located in an academic health center. The types of activities available to schools and colleges will be dependent upon what other health care educational programs exist within the university and/or the availability of other health care organizations in the area or region. The structural blocks for IPE are achieved by identifying and partnering with the available learning opportunities and locations in other health care educational programs and/or health care organizations; this represents a key first step for IPE activities. This work provides possible partners and locations as a function of the 5 models (described later) to assist faculty members and schools and colleges to develop their IPE experiences.

Faculty development is a key element in the development of IPE.2 Simply bringing faculty members from different health care disciplines into the same classroom, laboratory, simulation center, patient care facility, or other learning environment should not be assumed to result in a beneficial IPE experience for health care students. It becomes essential for colleges and schools of pharmacy, in conjunction with other health care educators and health care partners, to put into practice the faculty and clinician development programs and systems in various institutions/organizations focusing on (1) key elements underlying the purpose and goals of IPE activities, (2) ideal attributes and characteristics of IPE educators/clinicians, and (3) educational competencies, components, and activities for successful IPE. The development of skilled educators is an evolutionary process and should be based on the premise of educating collaborative, reflective practitioners capable of functioning effectively in an interprofessional healthcare team.

DIVERSITY OF INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION MODELS

A critical element of IPE is the availability of partners and settings that would enable opportunities for health professional students to engage in learning opportunities that affect their behavior in clinical situations. The nature and structure of these interactions and the partners involved in this process are varied based upon the model of pharmacy program:

(1) School/college of pharmacy is in a fully integrated academic health center (eg, University of Cincinnati);

(2) School/college is partially co-located program (ie, within the same region) with pharmacy and other professions under a common university ownership (eg, University of Connecticut);

(3) School/college is partially co-located program with pharmacy and other professions under different university components (eg, University of Texas);

(4) School/college with other health professions but no medical school (eg, Butler University);

(5) School/college with no other health education programs on campus (eg, Albany College of Pharmacy).

Interprofessional education usually involves educators and learners from 2 or more health professions and the nature of interactions should be focused on the learner with the educational goal of providing the knowledge, skills, and attitude/values focused on patient-centered care. Certainly, there are a variety of partners for schools and colleges located in a university with a fully integrated academic health center or in a university with a co-located health education program. Identification of available partners for schools and colleges without medicine but with other health care disciplines or those standalone schools without other healthcare professionals can be more challenging, but is not impossible if one considers other resources in the community and/or alternative approaches to provide learning opportunities. Individual schools and colleges should examine their university as well as surrounding colleges, practice sites, and community resources for potential collaborators for IPE.

Needs for each school/college may vary based on the organizational model, health professions available, and collaborative interest in IPE. IPE partnerships will occur most innately with those within the same university system (Types 1, 2, and 4) and between pre-established relationships with other healthcare education programs and practice settings. Schools without health professions co-located on their campus (Types 3 and 5) are likely to have the most difficulty and will require individual and creative approaches to implement IPE, especially in the didactic curriculum. These colleges may need to create new partnerships with other institutions of higher education that may or may not be in the same geographic location. While live face-to-face interaction is optimal, successful IPE learning opportunities could occur through technology with students at different locations. A list of possible partners for these various types of schools and colleges is provided in Table 1. These should be considered as potential partners and learning locations for interprofessional education; however, the list is not all inclusive and a school or college may partner with any profession related to patient care and in any location that supports interaction between professions.

Table 1.

Partners/Locations for IPE as Function of Pharmacy School/College Models

LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES AND LOCATIONS

A successful IPE learning opportunity should be a planned experience for all learners. It can include didactic instruction with or without a clinical experience, but it must be an intervention to assist the transformation of learners' attitudes, knowledge, skills, or behavior related to interprofessional care.3 In addition, an ideal intervention must include the opportunity for the students to perform some type of reflection as to their initial and changed perception of their role and value in interprofessional care. Students should receive feedback on their ability to reflect on their practice.4 Learning opportunities should be optimized to accommodate the programs of the various partners engaged in IPE; although, not every profession has to be involved in every IPE opportunity offered. This can be one of the greatest challenges, given the differences often seen among health education program structures (eg, curricular organization, semester or quarter schedule) and the difficulties encountered in working across administrative units or between different institutions to establish the necessary affiliation agreements.

Learning opportunities should be developed based upon the agreed learning outcomes for the students in the programs. A series of well-constructed and agreed upon outcomes incorporating knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors will serve as the foundation for the development of the specific learning activities or approaches. It will also form the basis for the development of the requisite learning assessments.

In addition to traditional hospital or clinic settings, possible learning locations include campus simulation centers, student health centers, or hospices or palliative care centers (Table 1). Certainly, the large classroom may be the location that is simplest and easiest to schedule for IPE. The essential element in any learning location must be that the site provides an environment for the team—learners and educators—to be engaged collaboratively and focus on the elements needed for interprofessional care. Careful consideration must be taken in deciding the timing and place of these learning locations in order to accommodate as many sets of learners as possible. These IPE experiences do not have to be offered in the traditional quarter or semester structure with weekly meetings. Instead, they could be conducted in a condensed time (eg, 1 or more weeks) throughout the academic year or even during the summer rather than over the course of an academic year. An intensive IPE experience (independent of other curricular requirements) could complement student learning conducted earlier in the semester or at the end of the academic year, which would enable the learner to focus on the critical elements in an IPE experience. A learning location must set all the participants on an equal footing, which is particularly important in the beginning of these experiences. Orienting all the learners to the location utilizing a team approach and allowing time for the IPE teams to form must be included in the learning opportunity. It may require several sessions for the IPE teams to start functioning collaboratively and there must be feedback to the learners as to the success and growth of their IPE teams.

Regardless of organization model, all colleges of pharmacy have some common needs and must confront several key issues to be successful in mounting an effective IPE component to their programs. Faculty members and students should appreciate the salience of IPE and its importance in the improvement of health care delivery and patient safety. Significant faculty and technological resources will be necessary for IPE implementation. Successful IPE implementation requires both faculty and administrative support. In this vein, administrative issues (including promotion and tenure) need to be aligned with changes that accompany IPE to enhance the potential for faculty buy-in. Finally, new IPE teaching and practice models need experimentation and evaluation.

FACULTY DEVELOPMENT

The AACP 2006-2007 Professional Affairs Committee identified that faculty development activities at the campus level are essential to the success of any IPE program. The Committee recommended AACP identify and share best practices in faculty development through its meetings, publications, and programs.5 Subsequently, the AACP Interim Meeting in February 2008 dedicated its keynote address to IPE and convened leaders of the other health professions organizations to share their perspectives on education and practice.6

Planning and developing an IPE course can be different in many ways from a course offered to only one profession. IPE can take a considerable amount of resources and time, reportedly requiring 3 times the preparation of a traditional course. To optimize the potential for a successful IPE initiative, the faculty members involved need initial preparation and continual development in this area.2 Historically, faculty members have not been trained to teach before being hired as educators; instead, they teach in ways similar to how they were taught, learn on the job, and/or grow through faculty development programs.

Implementing a Faculty Development Program

IPE is an enormous undertaking and there are tools faculty members can use to get started in and stay current with the field of IPE in the health professions. IPE faculty development should be initiated before the educational process begins. Faculty members must view faculty development as a vital component of IPE and not an added responsibility. In addition, faculty development affords faculty members from multiple disciplines the opportunity to interact early in the process of initiating IPE, while they are learning these skills together and forming team bonds. Typically, faculty members will start by duplicating the way they teach in their discipline of origin. Since different professions may have characteristic ways of teaching and learning, faculty members are likely to have internalized preferences for how they teach and interact with students. Likewise, a group of faculty members may bring their individual expectations of how the teaching will occur.2 Thus, it is essential that these experiences be shared among the faculty teams so that optimal strategies can be agreed upon.

Considerations in Implementing a Faculty Development Program for IPE

Professional development in IPE teaching is necessary due to certain issues related to this area. Faculty members often are skeptical about the value and benefit of IPE. Only recently has the effectiveness of IPE been documented.3,7,8 Educators also need to feel confident and secure about their knowledge base and sure of their ability to facilitate diverse groups of interprofessional learners. It is important for faculty to learn through the process of faculty development that teaching in an IPE environment is a shared responsibility. Additionally, as faculty members learn to work together to plan, develop, implement, teach, and evaluate courses and student performance, they serve as critical role models to the health professions students in their classes.2

Faculty members teaching in an interprofessional environment need to have the knowledge, skills, and values to successfully teach in this unique setting. Instead of teaching in a “silo,” faculty members will teach side by side with others who they may not know and will need to have the skills to adapt to both their colleagues and student participants. The healthcare system has a historical hierarchy among healthcare professionals that may yield power struggles when planning and teaching an interprofessional curriculum. Although we can assume that faculty members will have pertinent skills and knowledge in teaching, they may not have the skills necessary to perform IPE adequately.2

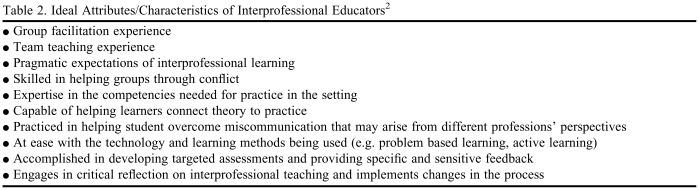

A starting point for faculty development in IPE is to identify the needs of the faculty members involved. Table 2 lists the ideal attributes/characteristics of interprofessional educators. Most faculty members will not be fully accomplished in all of the areas listed, and there may be common gaps or holes that many faculty members need to further develop. Common areas of faculty development for IPE include interactive teaching and learning, facilitated learning, group dynamics, conflict resolution, technology, working with unenthusiastic learners, and assessment strategies for IPE.2

Table 2.

Ideal Attributes/Characteristics of Interprofessional Educators2

Competencies for faculty members involved in interprofessional teaching are similar to competencies for students. Student competencies center on team organization and function; assessment and optimization of team performance; intrateam communication; conflict resolution and consensus building; leadership; and ability to set common patient care goals. Competencies for interprofessional teaching should include a commitment to IPE, understanding of roles and responsibilities in the different professions, positive role modeling, group dynamics, expert facilitation, valuing diversity, ability to use professional differences creatively within groups, and a deep understanding of and skill in using active learning methods.2,9

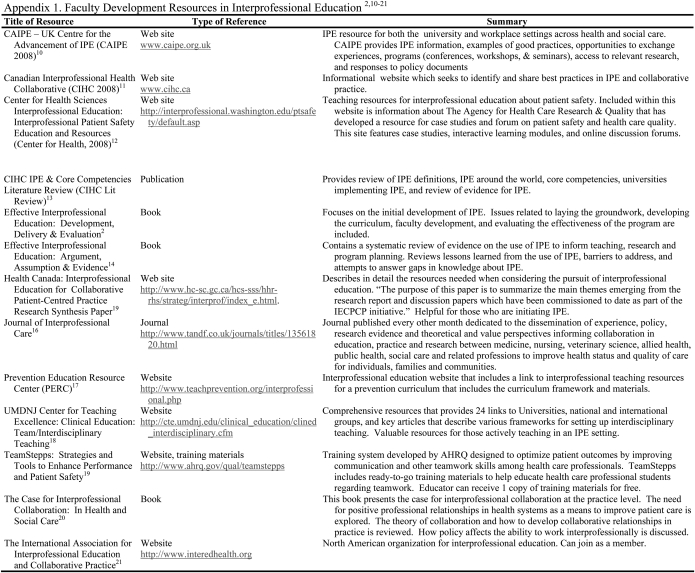

Becoming a skilled educator in IPE is an evolutionary process. First and foremost, faculty members need to have a shared understanding of the purpose and goals of IPE. It is also critical to engage in collaborative discussion regarding the pedagogical approach to IPE. Ultimately, development will occur through teaching in an IPE environment, critical reflection on the success and difficulties in the IPE setting, and making the necessary adjustments to improve the teaching. There are many resources to assist with faculty development in this area (Appendix 1).2,10-21 Most notably, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has developed a train-the-trainer system aimed at improving teamwork skills among health care professionals with the resulting educational goal of improving patient outcomes. The program includes extensive training materials (eg, preceptor guide, multimedia resource kit, and PowerPoint presentations) aimed at integrating principles of teamwork into a health care system. These resources can readily be adapted for team training of health professions education students in IPE. The examples and videos mimic real-world scenarios in which recommended communication tools can be utilized and evaluated in an IPE setting. This approach will help students see the immediate application of what they are learning.19 Appendix 2 outlines journal articles that are considered either best practice examples or helpful articles of interest for those initiating an IPE program at their university, academic health care center, or other academic setting.3,22-36

DISCIPLINE-INDEPENDENT CURRICULAR ELEMENTS IN IPE

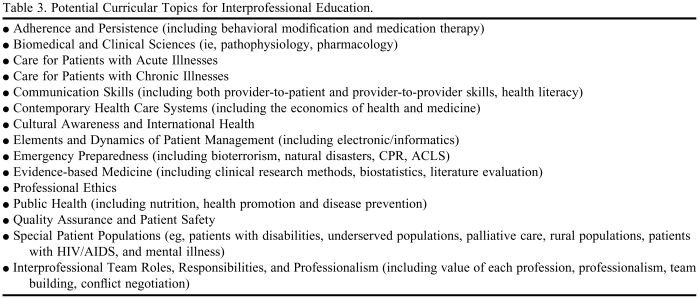

Many IPE articles describe the development, process, and/or function of healthcare teams in the educational setting.28,33,34 Some articles discuss success or barriers in the implementation of a specific course or curricular topic.23,36 However, few IPE articles provide a menu of various curricular topics that could be considered for IPE. Potential topics ideally suited for IPE are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Potential Curricular Topics for Interprofessional Education.

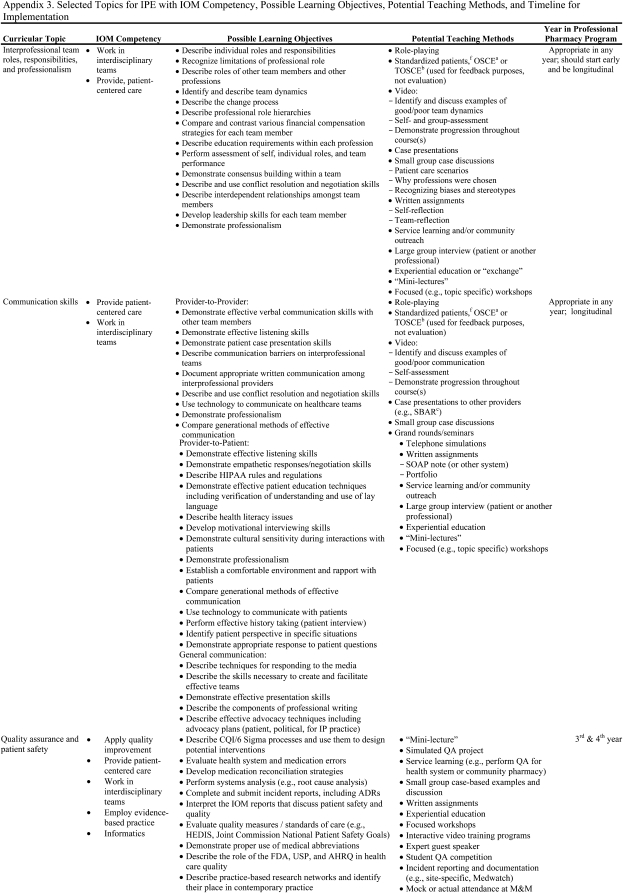

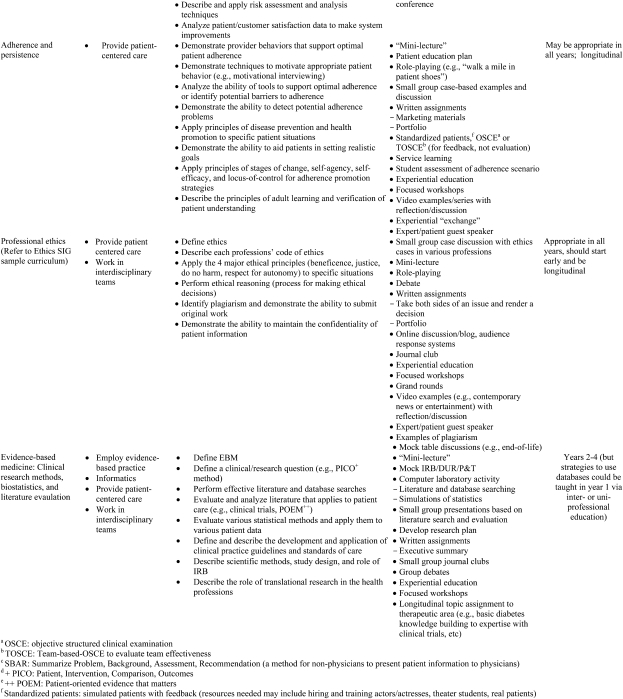

Regardless of the curricular topic chosen for IPE, we believe it should reflect the primary goal of IPE by developing a collaborative, reflective practitioner capable of functioning effectively in an interprofessional healthcare team. The topic should encourage critical thinking, self-assessment, and reflection. Additionally, the curricular topic should reflect some if not all of the 5 core competencies outlined by the Institute of Medicine: deliver patient-centered care, work as part of an interprofessional team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, focus on quality improvement approaches, and use information technology.37 Six specific topics, which lend themselves to IPE and the IOM criteria, are described in Appendix 3 with proposed learning objectives, teaching methods, and implementation timelines for pharmacy curricula.

SUMMARY

The value of IPE has been clearly outlined by the IOM and relevant literature. Educating health professions students in an interprofessional environment can lead to effective interprofessional health care teams, thus reducing medical errors and improving patient outcomes. Accreditation standards for pharmacy now include IPE as a recommended component of the curriculum and other health professions may soon follow. It is important to include certain critical elements when implementing IPE at any institution. Although schools and colleges at major academic health centers may have other professions readily available with whom to collaborate, IPE can be implemented at any school or college. Several curricular topics have been outlined that are best suited for IPE in health professions education and it may be easiest to begin with one of these. Most importantly, the IPE initiative should be evaluated and outcomes of the venture should be shared in a scholarly manner.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thanks members of the AACP Interprofessional Education Task Force who contributed to the development of some information included in this article. Many thanks to Richard Herrier who was a member of the 2005-2006 AACP Task Force and chaired the 2006-2007 AACP Task Force. Special thanks to Wendy Duncan-Hewitt, Task Force member from 2005-2008, Robert McCarthy Task Force member in 2006-2007, and Amy Broeseker Task Force member in 2007-2008.

Appendix 1. Faculty Development Resources in Interprofessional Education2,10-21

Appendix 2. Best Practices and Articles of Interest on Interprofessional Education3,22-36

Appendix 3. Selected Topics for IPE with IOM Competency, Possible Learning Objectives, Potential Teaching Methods, and Timeline for Implementation

REFERENCES

- 1. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree (2006). Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2000.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 2.Freeth D, Hammick M, Reeves S, Koppel I, Barr H. Effective Interprofessional Education: Development, Delivery & Evaluation. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Remington TL, Foulk MA, Williams BC. Evaluation of evidence for interprofessional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):70. doi: 10.5688/aj700366. Article 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallman A, Lindblad AK, Hall S, Lundmark A, Ring L. A categorization scheme for assessing pharmacy students' levels of reflection during internships. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1) doi: 10.5688/aj720105. Article 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroboth P, Crismon LM, Daniels C, et al. Getting to Solutions in Interprofessional Education: Report of the AACP 2006-2007 Professional Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6) Article S19. [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Interim Meeting Reports. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/meetingsandevents/IMPresentations/Pages/2008InterimMeeting.aspx. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 7. Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002213. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME Guide no. 9. Med Teacher. 2007;29:735–51. doi: 10.1080/01421590701682576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves S, Goldman J, Oandasan I. Key factors in planning and implementing interprofessional education in health care settings. J Allied Health. 2007;36:231–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Center for Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE). www.caipe.org.uk. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 11. Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. www.cihc.ca Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 12. Center for Health Sciences Interprofessional Education: Interprofessional Patient Safety Education and Resources. Available at: http://interprofessional.washington.edu/ptsafety/default.asp. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 13. Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. Interprofessional Education & Core Competencies. Available at: www.cihc.ca/about/curricula/CIHC_IPE-LitReview_May07.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 14.Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth D. Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument, Assumption & Evidence. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Health Canada: Interprofessional Education for Collaborative Patient-Centered Practice Research Synthesis Paper. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/hhr-rhs/strateg/interprof/synth_e.html Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 16. Journal of Interprofessional Care. Available at: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title∼db=all∼content=g912336992∼tab=summary. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 17. Prevention Education Resource Center (PERC): Interprofessional Education. http://www.teachprevention.org/interprofessional.php Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 18. Clinical Education: Team/Interdisciplinary Teaching, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. http://cte.umdnj.edu/clinical_education/clined_interdisciplinary.cfm Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 19. TeamStepps: Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/abouttoolsmaterials.htm Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 20.Meads G, Ashcroft J, Barr H, Scott R, Wild A. Health and Social Care. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2005. The case for interprofessional collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- 21. The International Association for Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. http://www.interedhealth.org/. Accessed April 17, 2009.

- 22.Johnson AW, Potthoff SJ, Carranza L, et al. CLARION: A novel interprofessional approach to health care education. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):252–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banks S, Janke K. Developing and implementing interprofessional learning in a faculty of health professions. J Allied Health. 1998;27(3):132–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett G, Greenwood R, Ross K. Integrating interprofessional education into 10 health and social care programmes. J Interprof Care. 2003;17(3):293–301. doi: 10.1080/1356182031000122915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper H, Carlisle C, Gibbs T, Watkins C. Developing an evidence base for interdisciplinary learning: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(2):228–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Eon M. A blueprint for interprofessional learning. Med Teach. 2004;26(7):604–9. doi: 10.1080/01421590400004924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeth D, Nicol M. Learning clinical skills: an interprofessional approach. Nurs Educ Today. 1998;18:455–61. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(98)80171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert JH. Interprofessonal learning and higher education structural barriers. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):87–106. doi: 10.1080/13561820500067132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon PR, Carlson L, Chessman A, et al. A multisite collaborative for the development of interdisciplinary education in continuous improvement for health professions students. Acad Med. 1996;71(9):973–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hope JM, Lugassy D, Meyer R, Jeanty F, Myers S, Jones S, et al. Bringing interdisciplinary and multicultural team building to health care education: The downstate team-building initiative. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):74–83. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horsburgh M, Lamdin R, Williamson E. Multiprofessional learning: the attitudes of medical, nursing and pharmacy students to shared learning. Med Educ. 2001;35(9):876–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindeke LL, Ernst L, Propes B, Edwardson S, Lepinski P, Ardito S, et al. A model of interdisciplinary education for inner-city health care. Nat Acad Pract Forum. 1999;1(2):95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements for interprofessional education. Part 1: the learner, the educator and the learning context. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):21–38. doi: 10.1080/13561820500083550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements of interprofessional education. Part 2: factors, processes and outcomes. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):39–48. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinert Y. Learning together to teach together: interprofessional education and faculty development. J Interprof Care. 2005;3(Suppl 1):60–75. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yarborough M, Jones T, Cyr TA, Phillips S, Stelzner D. Interprofessional education in ethics at an academic health sciences center. Acad Med. 2000;75(8):793–800. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]