Abstract

Student professionalism continues to be an elusive goal within colleges and schools of pharmacy. Several reports have described the nature of professionalism and enumerated the characteristic traits of a professional, but educational strategies for inculcating pharmacy students with attitudes of professionalism have not been reliably effective. Some authors have suggested the need for a standard definition. If the goal can be more clearly conceptualized by both faculty members and students, and the moral construct of the fiduciary relationship between pharmacist and patient better understood, the development of professional values and behaviors should be easier to achieve. This paper describes a new approach to defining professionalism that is patterned after Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. It includes the general concept of patient care advocacy as an underlying paradigm for a new pharmacy practice model, and defines 5 behavioral elements within each of the 3 domains of professionalism: competence, connection, and character.

Keywords: advocacy, fiduciary, patient care, professionalism, students, taxonomy

THE ELUSIVE GOAL OF PROFESSIONALISM

The professional development of pharmacy students has been the focus of considerable attention in recent years. Various terms are used to describe the topic, such as professionalization, professional socialization, and professionalism, which all mean basically the same thing—to demonstrate the attitudes, values, and behaviors of a professional. Regardless of the terminology, inculcating professional behavior into the performance pattern of pharmacy students is no easy task. Pharmacy appears to be a profession in search of professionalism.

The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy's Argus Commission reported in 1991 that many pharmacists lack pride in their profession and do not hold their professional self-worth in high regard.1 In 1995, Chalmers et al reported the findings of an AACP committee that was charged with exploring how schools of pharmacy could promote a professional/pharmaceutical care philosophy among students and faculty members.2 They found that faculty members had a limited understanding of the professional socialization process and that schools needed to plan professional development and academic learning as mutually dependent and reinforcing educational goals. The 2000 White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism addressed as its primary focus inconsistencies in how pharmacy students develop professionally.3 The report's conclusion stated, “A combination of factors in both pharmaceutical education and pharmacy practice serves to create inconsistent professional socialization throughout the pharmacy education process. This inconsistent socialization threatens the status of pharmacy as a profession and justifies immediate action on the part of pharmacy students, educators and practicing pharmacists.” In 2003, Hammer et al published the most comprehensive review to date on pharmacy student professionalism.4 Their report includes a call to action based on, “the critical and comprehensive need to address professionalism.”

THE NEED TO REDEFINE PROFESSIONALISM

Hammer and colleagues identified a lack of definition and of focus as challenges to developing student professionalism.4 Identifying optimal learning outcomes for professional development is difficult as long as the academy lacks consensus on a clear definition of professionalism. When planning comprehensive educational strategies, the desired outcomes need to be defined with specificity and clarity. Hammer et al suggested that if faculty members interpret professionalism differently, the professional development of students might be inconsistent and erratic despite the best of faculty intentions.4 This raises the possibility that while trying to solve the problem, faculty members might be inadvertently exacerbating it, due to differing perceptions about the nature of professionalism. One example that has been observed at Palm Beach Atlantic University relates to inconsistencies with which faculty members are in support of a dress code as part of the professionalization program. Students come to realize that some faculty members who routinely ignore dress code violations are not in support of the policy. This phenomenon not only undermines the policy, but the lack of faculty alignment in one area of professionalism breeds an insidious skepticism among students toward other professionalism initiatives as well.

Previously published professionalism assessment tools have included a broad range of behavioral traits.5,6 Pharmacist performance depends upon some traits that are uniquely professional, along with others that are equally important but not specifically limited to the professional realm, such as effective communication, honesty, and accountability – traits that apply universally to all job categories. The White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism lists 10 characteristics of a profession and 10 traits of a professional.3 The Medical Professionalism Project identified defining traits of professionalism from a physician perspective.7

The purpose of this paper is to propose a new way of defining professionalism that is designed to clarify educational goals that foster professional development. This new definition identifies the functional dynamics of professional behavior using the taxonomy of learning as a model.

FIDUCIARY RELATIONSHIPS AND THE MORAL NATURE OF PHARMACY

The key to professionalism is the fiduciary relationship. Zlatic describes the fiduciary relationship as a “faith” relationship and a covenantal relationship, in which the fiduciary provides special expertise to benefit the beneficiary, and the beneficiary, in turn, places trust in the fiduciary.8 The fiduciary nature of the student-teacher relationship correlates to that of the patient and pharmacist. Teachers and pharmacists must honor their duty to serve the needs of students and patients, respectively. Hafferty, in addressing the professional responsibilities of physicians, carries the fiduciary concept a step further. The foundation of a fiduciary relationship is not merely to serve the needs of another within one's realm of expertise, but to place the welfare of another ahead of one's own welfare.9 He quotes former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, “The hallmark of a profession is that its members place the interests of those they serve above their own.”9(p23) Reynolds defines medical professionalism as, “a set of values, attitudes, and behaviors that results in serving the interests of patients and society before one's own.”10 Reynolds further explains that the respect and trust accorded to physicians are direct results of their commitment to put the patient first.10 An altruistic mindset elevates the nature of the fiduciary relationship beyond responsibility and service to one of self-sacrifice. Altruism adds a moral dimension to the fiduciary relationship, and therefore, to professionalism.9

Pellegrino comments on the “deprofessionalization” of medicine as being a moral issue.11 He suggests that physicians who are able to honor their fiduciary responsibilities, despite external pressures to the contrary, are able to do so on moral grounds. Professionalism is built on a cognitive foundation, but professional expertise serves little purpose unless it is effectively applied with affective skill and a moral perspective.11,12 This becomes increasingly difficult amid a climate of declining professional ethics in which physicians are encouraged to practice social rather than individual patient ethics. Not surprisingly, the fiduciary nature of professionalism is being eroded within a society that promotes self-interest and moral relativism as norms.11

Duncan-Hewitt suggests that the ability to function professionally depends on one's level of cognitive/moral development.13 A student's level of moral reasoning and complexity of thought determine whether the requirements of a fiduciary relationship can be met. A professional level of cognitive development reflects such skills as self-directed learning, critical thinking, prioritization, personal responsibility, and the ability to balance one's self-interests with one's duties. Duncan-Hewitt further states that such skills are developed primarily through effective mentoring, but that some faculty members and preceptors have not attained a sufficient level of development to effectively professionalize others.13 Student attitudes toward professionalism actually tend to deteriorate during their years of training.14,15 Schwirian and Facchinetti demonstrated that student negativity toward pharmacy seemed to parallel faculty attitudes.14 Reynolds concluded that professionalism is best learned from clinical faculty role models who manifest values and beliefs that put the patient first.10

A NEW VISION OF PROFESSIONALISM

In 2003, a national survey was conducted to determine what schools of pharmacy were doing to enhance student professionalism.16 Few schools were approaching professionalism from a longitudinal, broad-based perspective to achieve meaningful change. The author of the study concluded the report by stating, “Based on the results of this survey, SOPs [schools of pharmacy] would benefit from the development of a consensus-based definition of professionalism and further study of the use of standardized instruments to measure professional development.”16

To have broad application as an educational tool, a definition of professionalism requires both simplicity and specificity. Simplicity facilitates a common understanding of the concept and greater consistency in its application. There is currently no widely accepted, unifying paradigm for the concept of professionalism in pharmacy. Pharmaceutical care seemed to have great potential to function in that capacity, but it has not materialized as such. Specificity is needed because educational strategies are most effective when geared to achieve specific learning outcomes, and assessment tools are most useful when based on valid, measurable criteria. Current definitions of professionalism, consisting mostly of lists of behavioral traits, do not adequately reflect the depth of personal and interpersonal dynamics that exist within professional relationships. A laundry list of professional traits, no matter how relevant, is not likely to account for the complexity of the processes involved. An educationally functional model is needed, one that addresses the fiduciary nature of professional relationships and integrates a moral construct. The definition must build on a foundation of cognitive ability with elements of affective and moral development, recognizing that professional behaviors stem largely from one's attitudes, values, and beliefs.

When designing a practical definition of professionalism it is best to begin with a simple, straightforward vision that is easy to conceptualize. Advocacy is a term that clearly conveys the essence of the fiduciary relationship. An advocate is a proactive “protector” who intervenes whenever necessary on behalf of the client. Advocates are constantly on the lookout to spot risks that need to be avoided or managed. They proactively seek to achieve optimal outcomes, rather than to merely avoid negative outcomes. In effect, an advocate says, “Don't worry, I've got your back.” Patient care advocacy is a powerful yet simple concept that focuses advocacy on patient-centered healthcare. The nature of advocacy in this context involves a specific pharmacist functioning as an advocate for the health and well being of a specific patient. A pharmacist functioning as a patient care advocate takes responsibility to intervene on behalf of the patient regarding any aspect of the patient's care, without having to be asked or expected to do so.

Illustrations of Patient Care Advocacy

Three simple illustrations can be used to help students and faculty members envision the concept of patient care advocacy. The first is “mom.” Patient care advocates should treat every patient with the same commitment to quality that they would demonstrate in caring for their own mothers (or any other special person in their lives). Who would not go above and beyond to take care of one's own mother? No self-respecting pharmacist would dispense a medication to his or her mother without comprehensive counseling, or return a written prescription to her with instructions to call the insurance company because the drug is not covered. All pharmacists have close friends and loved ones for whom they would spare no effort in providing the best possible service. That is the level of care that every patient deserves from every pharmacist. Greenland described his frustration over the inadequate care given to his mother by a fellow physician and commented, “Patients and families want us to show that we care and that we understand the strain and anxiety that illness can cause. In other words, our patients want exactly the same things for themselves that we want for our own mothers.”17

The second illustration of advocacy is that of a superhero. A superhero constantly patrols the area, spotting potential dangers and coming to the rescue without being asked or summoned. The public does not have to call 911 to get help from Superman or Wonder Woman. Pharmacists who function as patient care advocates are vigilant to protect patients from harm and diligent to intervene proactively on their behalf when circumstances warrant. The patient need not ask for help; the pharmacist determines when help is needed. The primary difference between a patient care advocate and a bona fide superhero is that the pharmacist wears a white coat instead of a colorful cape.

The third illustration of advocacy is that of the selfless servant, providing service from a pure sense of altruism. The historical depiction of Christ, washing the feet of his disciples, captures the essence of advocacy in this regard. Contemporary examples of compassionate servanthood include Mother Teresa, Ghandi, Albert Schweitzer, Martin Luther King, and others who base their lives on providing service selflessly, with no expectation of receiving anything in return. Advocacy in this light reflects pharmacists who sense being called to the profession of pharmacy as part of a higher purpose. Such pharmacists naturally gravitate to roles as patient care advocates because they find special meaning and value in serving the needs of others. Reynolds describes the “deprofessionalism” of medicine as being related to physicians who view medicine as a career rather than a calling.10 A sense of calling compels one to provide service of the highest quality for altruistic reasons, whereas a sense of career promotes the pursuit of impersonal standards of excellence.10

THE PROFESSIONALISM PYRAMID

Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives grew out of a perceived need for a common framework by which to describe student development.18 Without a standard set of descriptors, it is difficult to plan educational strategies and assess student performance. To meet the need for a clear and meaningful classification system of educational objectives, 3 domains of learning were identified within the taxonomy: cognitive, affective and psychomotor.18 Each of the 3 domains has been further classified into learning objectives that progress along a continuum, from lowest to highest complexity.

When dealing with a concept as elusive as professionalism, it is important to identify performance objectives that are well understood and to organize those objectives into a framework that reflects their interrelatedness. The resulting taxonomy serves as a model of how professional values link to professional behaviors. Zlatic emphasized the need to inculcate professional values within a systematic framework: “Needed are models in pharmacy education in which the enculturation of professional values and the development of character occur in premeditated rather than haphazard fashion within classrooms, experiential settings, and campus life.”19

To develop a taxonomic model of professionalism, the focus needs to shift from learning to performance. It does not matter how much a student knows about professionalism. What is important is how well a student performs as a professional. The usefulness of an organized taxonomy of professionalism depends on having developmental objectives that relate to performance in a professional setting.

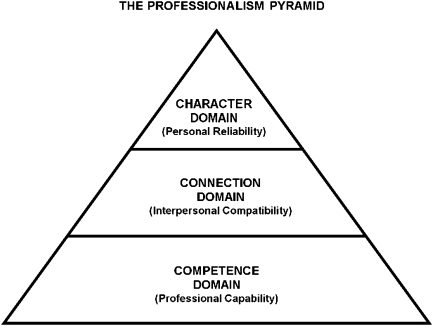

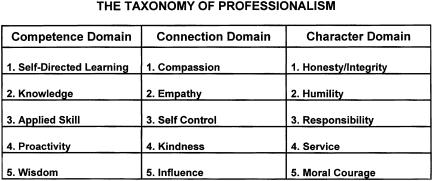

Professionalism can be envisioned as the product of 3 hierarchical domains of performance that can be represented as 3 levels of a pyramid, the Professionalism Pyramid (Figure 1). Within each of the 3 levels are 5 progressive performance objectives or elements of professionalism (Figure 2). The elements were identified by one of the authors over a 15-year period of iteration by closely observing pharmacist behavior in a variety of pharmacy settings. Each element was then compared against professionalism characteristics as reported in pharmacy and medical literature to confirm validity.3,4,7

Figure 1.

The hierarchical relationship between the 3 domains of professionalism. Competence (professional expertise) forms the basic foundation. The ability to connect effectively with people elevates one's professional capability to the next level. The highest level of professionalism, commensurate with strong fiduciary relationships, results from progressing to the character domain, which adds the dimensions of trust and morality.

Figure 2.

Five elements of professionalism found within each of the 3 domains of competence, connection, and character are listed, with the impact on professional behavior increasing progressively from number 1 through 5.

Taxonomy of the Competence Domain

The base of the Professionalism Pyramid forms the foundation upon which all other aspects of performance are built. This is the Competence Domain, representing basic pharmacist capability, or standard professional expertise. Without competence—the knowledge and skill to function at an acceptable level—a pharmacist should not be permitted to practice. The Competence Domain consists of the following performance objectives, listed from the lowest level to the highest level of competence. These 5 performance objectives progressively produce the capability to develop and apply one's professional expertise in pharmacy.

Self-directed learning.

Competence begins with commitment, an intrinsic motivation, to learn whatever is necessary to remain proficient. Without such commitment, it is only a matter of time before a competent graduate becomes an incompetent pharmacist. Self-directed learning involves the ability to recognize what one needs to learn and the capacity and motivation to learn it. For a professional, awareness of a lack of knowledge should create an unquenchable thirst that can only be relieved by filling the void through a self-initiated process of learning.

Knowledge.

A pharmacist must know about drugs, diseases, how drugs are used to prevent or treat disease, which complications can result, and how pharmacy systems interface with larger health systems. As represented by material covered on the North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination (NAPLEX), such knowledge is at the core of the profession, and without having demonstrated commensurate proficiency, one should not be licensed to practice pharmacy. Traditional pharmacy curricula generally focus heavily in this area.

Applied Skill.

Knowledge is of little use unless a pharmacist possesses the skill to apply it effectively in providing patient-centered care. Skill is the “know how” to apply what you know. It includes a variety of affective, cognitive and psychomotor processes and techniques, not the least of which is the ability to multitask. Professionals bridge the gap between knowledge and application.

Proactivity.

Knowledge and skill are of no value unless the pharmacist takes action to put them to good use. In terms of improving health outcomes for a specific patient, there is no difference between a competent pharmacist who chooses not to act and one who lacks the competence to act in the first place. Basketball players are not able to score any points without first taking a shot, no matter how knowledgeable or skillful they might be in the art of shooting a ball through a hoop. Proactivity begins with initiative and evolves into perseverance in order to translate potential outcomes into actual results.

Wisdom.

At the highest level of competence, professionals must be able to exercise sound judgment, make wise decisions, and solve problems by thinking critically and carefully analyzing options. Wisdom is the capacity to effectively apply knowledge and skill. It encompasses the full spectrum of analytical thought from the highest levels of abstract reasoning to the most basic applications of common sense.

Taxonomy of the Connection Domain

For pharmacists to effectively apply their knowledge and skill in a “real life” setting, competence is not enough. Pharmacists must also possess the capacity to connect with other people through meaningful communication and to develop positive social relationships. This is the Connection Domain, representing interpersonal compatibility. The elements of this domain could be referred to collectively as “people skills,” which include basic communication skills, self-control, and the general ability to get along with others. Pharmacists must relate to patients, coworkers, and other health professionals, often amid stressful or chaotic circumstances. The ability to constructively connect with others greatly enhances a pharmacist's capacity to serve effectively as a patient care advocate. Connection falls largely into the affective domain of learning and depends heavily on emotional and social skills.20 Although the impact of emotional intelligence on pharmacist performance has not been clearly defined, 2 fundamental abilities, the capacity to be aware of and manage one's own emotions, and the capacity to interact socially and maintain positive relationships with others, play a role in how effectively a pharmacist connects with others on a professional level.21

The Connection Domain consists of the following performance objectives, listed from the lowest level to the highest level of connection. These 5 performance objectives progressively produce a level of compatibility that results in constructive relationships and the ability to function well as part of a team.

Compassion.

Compassion is the foundation of a win/win attitude. As the saying goes, “people don't care how much you know until they know how much you care.” Sincerely caring about others is requisite to being able to connect with them. When patients sense that a pharmacist has their best interest at heart, new channels of communication begin to open and they become more receptive to the message.

Empathy.

It is not possible to achieve win/win outcomes without first gaining insight into the other person's definition of winning. Communication barriers begin to dissolve when an empathic pharmacist sincerely seeks to understand how the other person thinks and feels. Patients are more trusting and receptive to input from pharmacists when they feel understood. Empathy is most effective when the patient is approached holistically, with consideration of his or her spirituality, cultural/ethnic diversity, socioeconomic status, educational background, and the psychology of specific illnesses or health factors.

Self-control.

Compassion and empathy convey a caring attitude toward patients. However, a positive, caring attitude can be undermined if the pharmacist is not able to maintain a stable affect. If a pharmacist's behavior becomes a labile product of his or her emotions, even the most altruistic of intentions could be derailed. Pharmacists who allow their behavior to deteriorate when they are stressed or upset will find their capacity to function as a patient care advocate significantly diminished.

Kindness.

Pharmacists who project a kind, personable demeanor create a welcoming atmosphere that puts patients at ease. By demonstrating unconditional courtesy, respect, and warmth toward all people, simply by virtue of their intrinsic human dignity, connections are strengthened and solidified. This element also encompasses traits such as patience and tolerance, which can help pharmacists cope with the inevitable shortcomings and imperfections of others, and maintain grace under pressure.

Influence.

The highest level of connection is influence. This element involves the wherewithal to motivate and inspire other people. A pharmacist at this level is able to progress from being a cooperative team player to being an influential leader. This level of connection enables the pharmacist to effect change in a patient's behavior, especially when cognitive behavioral strategies are employed, such as motivational interviewing. Influence is the functional foundation of leadership.

Taxonomy of the Character Domain

For a pharmacist to reach the pinnacle of professionalism—the top of the pyramid—character is the final domain, leading to personal reliability. Character is the key to trustworthiness, without which a fiduciary relationship cannot thrive. A pharmacist of character functions from a solid base of morality and ethics. This requires a clear sense of right and wrong based on ethical professional standards and a well-defined foundation of moral truth. For some, the source of truth may be religious or spiritual in nature, such as the Judeo-Christian Bible or the Koran. For others, moral and ethical standards might come from societal norms or philosophies.

Character implies that one has the integrity to be consistent in distinguishing right from wrong, and the moral courage to act accordingly. Professionals of character perceive that they are part of something larger than themselves and that their lives have meaning.22 This may involve a sense of being “called” to the profession of pharmacy in order to provide necessary services to patients in need. Pharmacists who feel an altruistic drive to function as patient care advocates are more likely to behave in a reliable manner, due in large part to constancy of purpose. Absent a moral influence, self-interest might tend to weaken the fiduciary commitment, and one's motivation to serve would be more subject to the influence of changing circumstances or conditions.11 The Character Domain consists of the following performance objectives, listed from the lowest level to the highest level of character.

Honesty/Integrity.

The most fundamental aspect of character involves authenticity. Pharmacists need to be open and honest as the first step in earning trust. Moral integrity implies that decisions and behaviors are consistent, based on values that are grounded in unchanging principles. People can count on a pharmacist who displays honesty and integrity to be reliable.

Humility.

The ability to progress to higher levels of character depends on having a humble attitude. Humility dissuades pharmacists from feeling that tasks are beneath them or that other people are not worthy of their service. Servant-leadership is grounded in humility. This is also the key to a strong fiduciary relationship in which the provider places the interests of the beneficiary ahead of his own. A humble pharmacist is more concerned about a positive outcome for the patient than about personal recognition or reward.

Responsibility.

Responsibility leads to accountability. People of character assume a level of personal responsibility that ensures attention to whatever needs to be done. They do not have to be told what to do but function from a sense of duty. They hold themselves accountable when things do not work out as planned rather than instinctively making excuses or blaming others. A sense of responsibility is what provides the motivation to perform all necessary tasks with a commitment to excellence, even when no one is watching.

Service.

The next level consists of an altruistic desire to serve the needs of others, through which service is not seen as a burden or a bother. A service mentality creates a natural desire to help other people and generates true satisfaction from performing such service. People at this level of character gravitate to service professions and are able to maintain a positive outlook toward service despite occasionally having to serve clientele who are difficult or demanding.

Moral Courage.

Moral courage is the wherewithal to do what one knows to be right even when unpleasant consequences might result. A service-minded pharmacist who lacks moral courage might be inclined to withhold or restrict service amid extenuating circumstances, such as a busy workload, lack of resources, or other external pressures. Adding the dimension of moral courage provides a compelling desire to follow an altruistic course despite conflicting urges to pursue a path of self-interest. Pharmacists who exhibit moral courage hold true to their beliefs even when it is risky, inconvenient, or unpopular to do so. Stephen R. Covey relates moral courage to the concept of conscience, which he describes as the moral law within each of us, “that still small voice within that assures you of what is right and that prompts you to actually do it.”23 At this level of character, patients come to know that if there is any way possible to provide needed service, this pharmacist will find a way to do it. That understanding between a pharmacist and a patient epitomizes the power of a fiduciary relationship.

In summary, true patient care advocates are servant-leaders who demonstrate excellence with character by being fully adept in all 3 domains of professionalism. They are likely to be trusted and valued by those they serve and respected as leaders by those with whom they work. Their capability, compatibility, and reliability synergize in the workplace to produce optimal patient outcomes, while inspiring others to do the same.

FOSTERING PROFESSIONALISM

In addition to the formal curriculum of a pharmacy school, which is strictly controlled by faculty members, there is a “hidden” or “informal” curriculum within a school's culture that sometimes sends contradictory messages to students about professional values.9 Coulehan and Williams addressed this topic from the perspective of tacit vs. explicit learning.24 Tacit socialization refers to what students pick up from continual casual exposure to the learning environment without explicitly being taught. Explicit learning involves formal study and discussion. Tacit learning often trumps explicit learning and can significantly undermine the development of sound professional values. However, if a school's culture can be transformed, such that tacit learning of professionalism is more in concert with the professional goals of the curriculum, tacit learning could then serve as a powerful reinforcement for desirable professional values.

Attention to professional socialization should be longitudinal, pervasive, and consistent.25 Attitudes and behaviors of students can change for the better as a result of being immersed in a culture that heavily promotes professionalism over time and holds students accountable for professional growth. Experience at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy has shown that culture change can be accomplished, with a corresponding improvement in student professionalism.26 The School of Pharmacy at Auburn University has taken a more comprehensive approach to instilling professional values and reports signs of success.27 Hammer et al provide a detailed, comprehensive explanation of strategies that can be used to develop a culture that promotes professionalism.4

No quick fix or sudden cultural transformation can instantaneously eliminate unprofessional behavior or cause professional behavior to flourish. Nevertheless, a culture of professionalism can be gradually cultivated if there is widespread faculty buy-in and a willingness to persist. A clear and simple definition of professionalism, based on the reaffirming image of “patient care advocacy” as a practice model, might help students to internalize a more altruistic concept of pharmacy practice. The School of Pharmacy at Samford University has incorporated a unique program into new student orientation, in which great works of literature are used to impress upon students the moral dimension of being “called to serve,” which the authors suggest to be the core element of professionalism.28

Culture change can also be accomplished by faculty members being vigilant to identify unprofessional influences and to vigorously defend professional values with “counter-detailing.” Students need constant reassurance from counter-arguments to offset negative influences. This is akin to “inoculating” them against infectious antiprofessional attitudes to which they unwittingly might be exposed. Most importantly, the culture of a pharmacy education community must be rife with positive professional role models. Faculty members must “walk the talk” and project a credible message of professionalism by personally demonstrating advocacy. Fjortoft emphasized that faculty members can exert greater influence if students sense that their teachers care about them.29 If students witness inconsistencies between the content of the message and the behavior of the messenger, they will eventually cease to listen to the messenger. Pharmacy faculty members must model professionalism at every turn. Professionalism begets professionalism. If students personally experience advocacy from their teachers, they will be more inclined to assume the role of advocate toward patients. This concept should become a major focus of faculty development and preceptor training programs in the future. The New Testament expresses it thusly: “Whoever sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and whoever sows generously will also reap generously.”30 One way to strengthen the message is to deliver it as a consistent theme from the perspective of multiple disciplines, as reported by the colleges of pharmacy and nursing at the University of Cincinnati.31

APPLICATIONS

Because patient care advocacy and the taxonomy of professionalism are newly proposed concepts, there is little direct experience to report at this time. Results of various professionalism initiatives, all of which predate the taxonomy, are described elsewhere in this report. To illustrate potential applications of the taxonomy, preliminary efforts to inculcate these new professionalism concepts into the learning process at the Lloyd L. Gregory School of Pharmacy at Palm Beach Atlantic University (PBAU) are briefly described. Located in West Palm Beach, Florida, the school enrolled its first class in 2001 and has a class size of approximately 75. It is currently in the second year of a 3-year curricular revision. PBAU is a non-denominational Christian university, but admits students of all faith backgrounds.

Curriculum.

Nothing that takes place in pharmacy school, curricular or otherwise, is more important than introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) when it comes to inculcating the right professional values. The potential to shape the early development of professional values is arguably the greatest benefit of a comprehensive IPPE program. IPPE that focuses primarily on the acquisition of basic skills within the Competence Domain offers students little value beyond traditional intern work experience. At PBAU, IPPE learning outcomes have been carefully crafted to include elements of the Connection Domain and Character Domain. All 3 years of IPPE include on-campus group discussions and personal reflections guided by faculty coordinators, to ensure that students receive a consistent message of professional values and moral principles. Standardized IPPE learning activities are directed from campus. Upon each site visit, all students are required to complete an assignment that relates their unique experiences at the site to a universal learning outcome. IPPE requirements at PBAU include regular self-reflection entries into an electronic journal. Reflection journals are evaluated by faculty members and specific written feedback is provided to each student.

Three new didactic courses have been specifically designed to inculcate key concepts of the taxonomy. Spiritual and Professional Values in Healthcare is a 1 credit-hour course that relates the 3 domains of professionalism to well-known biblical principles, such as the Golden Rule, and to Stephen R. Covey's 8 habits of highly-effective people.23,32 Covey's first, second, and third habits of personal effectiveness correlate well to the Competence Domain and the fourth, fifth, and sixth habits of interpersonal effectiveness correlate to the Connection Domain.32 The last 2 habits impact character. The seventh habit focuses on balancing the personal and professional sides of life by paying equal attention to the spiritual, mental, physical, and social/emotional dimensions.32 The eighth habit emphasizes the importance of discovering and optimizing one's unique personal significance, which Covey defines as “voice” or calling, where talent meets need and action is fueled by passion and conscience.23 Psychosocial, Spiritual, and Cultural Aspects of Illness is a 2 credit-hour course designed to assist students in empathizing with patients on a higher level so as to better advocate for their specific needs. Community Service and Medical Missions is a 1 credit-hour service-learning course. This course is designed to build on the success of an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) elective that allows students to receive academic credit for participating in an overseas medical mission trip under faculty supervision. Faculty members who supervise such trips have reported numerous examples of students whose attitudes toward service and advocacy were radically transformed by their experiences. Research has begun at PBAU to identify the contributing factors of the missions experience that might have precipitated such dramatic personal transformations and explore whether those factors can be reproduced by other types of student activities.

Assessment.

Perhaps the greatest professionalism challenge facing academia is the task of objectively measuring professional values and behaviors. Although valid assessment tools have been developed, no standard approach to measuring professionalism has emerged.5,6 The advent of student portfolios and growing interest in continuous professional development will help students develop critical self-assessment habits and assume responsibility for their own professional growth. In this regard, self-reflection is an important component.10 At PBAU, a Professionalism, Service and Leadership Committee is developing specific professionalism outcomes that will be monitored via student portfolios. A student self-assessment form was implemented last year, with a requirement that students complete the form and discuss it with their respective advisors annually.

The nature of professionalism is such that student self-assessment and preceptor assessment can serve as meaningful formative measures, but cannot be relied upon as definitive summative measures. Behavioral assessments conducted prior to graduation are prone to being influenced by student motivation to achieve a desired grade, rather than being reflective of the student's true value system. In contrast, postgraduate employer surveys offer the potential of providing useful summative data regarding the professionalism of a school's graduates, based on graduates' actual performance as practicing pharmacists. Postgraduate employer surveys need to be developed, standardized, and widely utilized by the academy.

Admissions.

Paying attention to all 3 domains of professionalism can aid in evaluating the qualifications of applicants to a pharmacy program. This is particularly true in light of the lucrative salaries and abundant job opportunities that are attracting people to pharmacy who might be more concerned about financial security than service to mankind. Grade point average and the results of the Pharmacy College Admission Test (PCAT) focus mostly on the Competence Domain. Regrettably, there is no blood test or electronic scan that can be used to measure the character, morality, or commitment of pharmacy school applicants. Although these traits are not as quantifiable as one's academic background, they are just as important in estimating one's suitability to practice pharmacy. At PBAU, all applicants must complete a supplemental application that includes a written statement about why the applicant is applying to PBAU. Applicants are also required to attend an onsite interview. This affords faculty members an opportunity to assess the applicant's communication and social skills and to determine whether the applicant seems to be a good “fit” for pharmacy. The onsite visit also enables representatives of the school to inform applicants about the uniqueness of the School's culture and curriculum, including expectations pertaining to morality and character. One vital component of the interview process is to have applicants write a short essay on a values-related topic. This enables the admissions team to assess the applicant's writing and critical-thinking skills and provides additional insight into the applicant's values. Lastly, applicants' backgrounds are reviewed for signs of volunteerism, leadership, and other forms of altruistic extracurricular involvement suggestive of a proactive service mentality.

CONCLUSION

The taxonomy of professionalism is a non-vetted conceptual model that warrants further review to determine its role, both in pharmacy education and in the pharmacy workplace. It has the potential to be of functional value because it produces a consistent image of professional behavior that can be clearly visualized and easily articulated, despite the complexity of the interpersonal dynamics that are involved. The basic concept of a pharmacist as a patient care advocate enhances the utility of the model by creating a common paradigm to which students, faculty members, preceptors, and practitioners can readily relate. Nevertheless, the 3 domains of professionalism need to be validated in a variety of pharmacy practice settings, and the specific elements within each domain must be critically compared to existing professionalism assessment criteria and pharmacist performance standards. If, in the final analysis, this new way of framing professional development better enables students and faculty members to visualize what professionalism is, conceptualize how professionalism works, and analyze how well professionalism is being executed, a new standard of pharmacy practice might evolve that more closely resembles a patient care advocacy model. Should that come to pass, pharmacy would no longer be a profession in search of professionalism, and trust might once again become the defining element in the relationship between pharmacists and the public they serve.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller WA, Campbell WH, Cole JR, et al. The choice is influence. The 1991 Argus Commission Report. Am J Pharm Educ. 1991;55(Suppl):8S–11S. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalmers RK, Adler DS, Hadad AM, Hoffman S, Johnson KA, Woodard JMB. The essential linkage of professional socialization and pharmaceutical care. Am J Pharm Educ. 1995;59(1):85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.APhA-ASP/AACP-COD. Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40(1):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3) Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammer DP, Mason HL, Chalmers RK, Popovich NG, Rupp MT. Development and testing of an instrument to assess behavioral professionalism of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(2):141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chisholm MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK. Development of an instrument to measure professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4) doi: 10.5688/aj700485. Article 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medical professionalism project. medical professionalism in the new millennium: A Physicians' Charter. Lancet. 2002;359(9305):520–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zlatic TD. Re-visioning Professional Education: An Orientation to Teaching. Kansas City, Mo: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2005. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafferty FW. In search of a lost cord – professionalism and medical education's hidden curriculum. In: Wear D, Bickel J, editors. Educating for Professionalism – Creating a Culture of Humanism in Medical Education. Iowa City, Ia: University of Iowa Press; 2000. pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds PP. Reaffirming professionalism through the education community. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(7):609–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-7-199404010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pellegrino ED. Medical professionalism: can it, should it survive? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13(2):147–9. doi: 10.3122/15572625-13-2-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown DL, Ferrill MJ, Hinton AB, Shek A. Self-directed professional development: the pursuit of affective learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65(3):240–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan-Hewitt W. The development of a professional: reinterpretation of the professionalization problem from the perspective of cognitive/moral development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(1) Article 06. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwirian PM, Facchinetti NJ. Professional socialization and disillusionment: the case of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1975;39(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duke LJ, Kennedy WK, McDuffie CH, Miller MS, Sheffield MC, Chisholm MA. Student attitudes, values and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5) Article 104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sylvia LM. Enhancing professionalism of pharmacy students: results of a national survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4) Article 104. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenland P. What if the patient were your mother? Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(6):607–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS, Masia BB. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The Classification of Educational Goals. Book 2 Affective Domain. White Plains, NY: Longman; 1964. pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zlatic TD. Re-visioning Professional Education: An Orientation to Teaching. Kansas City, MO: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2005. p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goleman D. Social Intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Dell; 2006. p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romanelli F, Cain J, Smith KM. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of academic and/or professional success. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3) doi: 10.5688/aj700369. Article 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lennick D, Kiel F. Moral Intelligence. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing; 2008. pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Covey SR. The 8th Habit – From Effectiveness to Greatness. New York: Free Press; 2004. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coulehan J, Williams PC. Professional ethics and social activism – Where have we been? Where are we going? In: Wear D, Bickel J, editors. Educating for Professionalism – Creating a Culture of Humanism in Medical Education. Iowa City, Ia: University of Iowa Press; 2000. pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammer DP. Professional attitudes and behaviors: the “A's and B's” of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(4):455–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Morgan JA, Rodriguez de Bittner M. Professionalism: A Determining Factor in Experiential Learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710231. Article 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger BA, Butler SL, Duncan-Hewitt D, et al. Changing the Culture: An Institution-wide Approach to instilling Professional Values. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1) Article 22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumgartner GW, Spies AR, Asbill CS, Prince VT. Using the Humanities to Strengthen the Concept of Professionalism Among First-Professional Year Pharmacy Students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710228. Article 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fjortoft N. Caring Pharmacists, Caring Teachers. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1) Article 16. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Men's Devotional Bible New International Version. Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan; 1993. 2 Corinthians 9:6; pp. 1254–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brehm B, Breen P, Brown B, et al. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Producing Professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4) doi: 10.5688/aj700481. Article 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1989. [Google Scholar]