Abstract

Reaction of isopropyl[(2-pyridyl)alkyl]amines such as N-isopropyl-N-2-methylpyridine or N-isopropyl-N-2-ethylpyridine with aqueous solutions of NaAuCl4 led to the formation of [LAuCl2][AuCl4] in low yields, where L = pyridyl amine bound to gold in a bidentate fashion. Reaction of 2-(3,5-diphenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine with aqueous NaAuCl4, however, proceeded with formal loss of HCl and direct formation of the gold(III) amido complex L'AuCl2, where L' = deprotonated pyrrolyl ligand. Optimization of the reaction conditions to make the new amido complex identified MeCN:H2O (1:2) as the best choice of solvent, affording product in 92 % yield. This dichloro amido complex is a convenient precursor to L'AuMe2, which was found to be air-stable and thermally robust.

Introduction

Although the chemistry of gold has recently undergone a renaissance in synthetic organic chemistry,[1-13] catalysis involving two electron redox processes such as oxidative additions and reductive eliminations has been slower to develop.[14-16] This is perhaps surprising, as the reductive elimination of organics like ethane from gold dimethyl complexes has been known for some time. These reductive elimination reactions have been exploited in materials and heterogeneous chemistry, where the clean loss of gaseous ethane has popularized the use of gold dimethyl complexes in the syntheses of supported gold catalysts and as chemical precursors to gold nanoparticles.[17-35] With such practical uses for gold(III) dialkyl complexes, fundamental studies on the synthesis of new derivatives, as well as on the kinetics and mechanism of reductive elimination of cross-coupled alkane are of significant importance.

In general, the rate of alkane loss from gold dialkyls greatly depends on the structure of the organometallics. For instance, Me4Au2I2 (1) is known to detonate violently upon melting at 78°C (eq 1).[36] (PR3)AuMe2X complexes also thermally lose ethane (eq 2) with rates that are sensitive both to the nature of X- and the nature of the phosphine ligand.[37-44] The mechanism of ethane formation from 2 (eq 2) is believed to first involve dissociative loss of a phosphine, as the rates are severely retarded in the presence of excess phosphine.[41-43, 45] A similar dissociative mechanism is believed to take place with gold acetylacetonate complexes 3 (eq 3), where one arm of the chelate dissociates to form a T-shaped intermediate before loss of ethane occurs.[46]

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

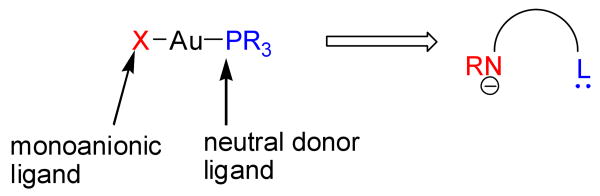

We are interested in the reductive elimination chemistry of gold because of its relevance to the emerging field of alkyl-alkyl cross-coupling chemistry.[47-54] Equations 1-3 suggest that if a AuIII(Ralkyl)(R'alkyl) species can be formed under conditions typically employed for cross-coupling reactions, then depending on the ligand, reductive elimination of cross-coupled alkane could indeed occur. Catalysis would additionally require that the resulting Au(I) fragment be capable of oxidatively adding an alkyl electrophile, and there are in fact reports of facile gold-mediated oxidative additions of alkyl halides with (PR3)AuX.[55-58] We wondered if new amido complexes could be developed that might be able to mimic the reductive elimination and oxidative addition chemistry of the well-known gold phosphine complexes (Figure 1). Amido-based ligands were chosen as targets because their amine precursors are air-stabile and relatively easy to prepare, and because they could potentially support the Au(I)-Au(III) redox cycle shown in Scheme 1. This cycle involves d8 and d10 gold intermediates that are also isoelectronic with the Pd(II) and Pd(0) intermediates that are well-known to catalyze aryl-aryl cross-coupling reactions.

Figure 1.

Replacing the halide in XAuMe2PR3 with an amido moiety is part of our strategy for developing new ligands for gold catalysts. The known reactivities of XAuPR3 complexes towards oxidative additions and of XAuMe2PR3 complexes towards reductive eliminations inspire this approach.

Scheme 1.

Possible catalytic cycle involving gold-amido complexes in cross-coupling catalysis.

With the new amido ligands, it will be especially important to study the relationship between ligand dissociation from 4 to 5 with catalytic cross-coupling activities, as reductive eliminations of alkane from amido dialkyl complexes of gold may also require the initial formation of a three-coordinate species. We anticipated that ligands 6-8 (Chart 1), once deprotonated and bound to gold, will have varying degrees of flexibility and will allow us to probe systematically the effect of coordination environment on the reductive elimination step described in Scheme 1. Our lab is working to prepare well-defined gold dimethyl complexes based on 6-8, and here we report progress towards that goal.

Chart 1.

Precursors to the amido ligands targeted for this study.

Results and Discussion

Addition of one equivalent of the aminopyridine ligand 6 to an aqueous solution of NaAuCl4 led to an instant precipitation of the new gold complex 9 (eq 4) in moderate yields. The precipitate was immediately filtered, as it was found that continued stirring of the resulting suspension led to eventual redissolution of 9 to afford a complex mixture which we were unable to characterize. Once complex 9 has been isolated, however, it is quite stable in organic solvents. X-ray quality crystals were grown by vapor diffusion of diethyl ether into an acetonitrile solution of 9 to give bright yellow crystals.

|

(4) |

The ORTEP diagram of 9 is shown in Figure 2, and the X-ray structure confirms a cationic gold complex containing a AuCl4 counter-ion. The N2AuCl2 (where N2 = N-isopropyl-N-2-methylpyridine) cationic core of 9 adopts a square-planar arrangement typically seen for d8-metal complexes. The nitrogen atom of the amino ligand retains its tetrahedral geometry, which places the i-propyl ligand above the plane of the pyridine ring. Additionally, the steric bulk of the organic ligand was found to be relatively shielding, as no intermolecular Au···Au or Au···Cl contacts closer than the sum of the van der Waals interactions were observed in the solid-state packing diagram.

Figure 2.

ORTEP diagram of 9. Ellipsoids shown at the 50 % level. Selected bond lengths (Å): Au(1)-N(1) 2.024(7), Au(1)-N(2) 2.046(7), Au(1)-Cl(2) 2.264(4), Au(1)-Cl(1) 2.266(4), Au(2)-Cl(3) 2.278(4). Selected bond angles (°): N(1)-Au(1)-N(2) 82.7(3), N(1)-Au(1)-Cl(2) 175.19(19), N(2)-Au(1)-Cl(2) 92.8(2), N(1)-Au(1)-Cl(1) 94.8(2), N(2)-Au(1)-Cl(1) 176.12(19), C(6)-N(2)-C(7) 113.8(6), C(5)-C(6)-N(2) 110.5(6).

Similar coordination chemistry to gold was observed with the ligand 7, which contains an extra methylene group in the amino linker. Upon addition of 7 to an aqueous solution of NaAuCl4, complex 10 was found to immediately precipitate from solution (eq 5).

|

(5) |

The ORTEP diagram of 10 is shown in Figure 3, and the X-ray structure confirms the bidentate coordination of 7 leading to a six-membered ring. A substantial pucker in the metallacycle is required to achieve a planar N2AuCl2 core in 10 (N2 = N-isopropyl-N-2-ethylpyridine), and the plane of the pyridine ring is now substantially twisted out of the Cl(1)-Au(1)-Cl(2) plane. Again, pairing of the amino-gold cation with a AuCl4 counter-ion was observed. Synthetically, methods to prepare the cationic amino complexes 9 and 10 without the AuCl4 counter-ion are much more desirable. Not only would such methods provide cheaper amino complexes by using half the amount of gold, but they would also afford intermediates that could potentially be converted to the desired amido complexes without the inherent purification problems involved when using 9 and 10. Therefore, the search for alternative methods to prepare [LAuCl2]Cl, where L = 6 or 7, or their amido derivatives, is ongoing in our labs.

Figure 3.

ORTEP diagram of 10. Ellipsoids shown at the 50 % level. Selected bond lengths (Å): Au(1)-N(1) 2.027(6), Au(1)-N(2) 2.071(8), Au(1)-Cl(2) 2.268(4), Au(1)-Cl(1) 2.276(6), Au(2)-Cl(4) 2.275(3), Au(2)-Cl(6) 2.278(3), Au(2)-Cl(5) 2.279(6), Au(2)-Cl(3) 2.280(6). Selected bond angles (°): N(1)-Au(1)-N(2) 91.3(3), N(1)-Au(1)-Cl(2) 177.77(15), N(2)-Au(1)-Cl(2) 86.5(2), N(1)-Au(1)-Cl(1) 91.6(2), N(2)-Au(1)-Cl(1) 176.32(15), C(1)-C(6)-C(7) 111.7(6), N(2)-C(7)-C(6) 112.9(6).

|

(6) |

The coordination chemistry of the 2-(3,5-diphenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine ligand (8) with gold was substantially different than the amino-pyridine ligands 6 and 7. When mixed with aqueous NaAuCl4, ligand 8 led directly to the desired amido complex 11 without proceeding through intermediate AuCl4 salts of the amine (eq 6). The reaction proceeds through the formal loss of HCl and the precipitation of the red-brown amido complex 11 in high isolated yields (eq 6). Optimization of this reaction identified MeCN:H2O (1:2) as the best choice of solvent, affording 11 in 92 % yield. Interestingly, addition of extraneous bases like NEt3 did not promote the reaction, but in fact led to lower yields of 11.

The X-ray structure of 11 is shown in Figure 4. The Au-Cl bond trans to the anionic ligand measures 2.280(8) Å and is slightly longer than the Au-Cl bond trans to the pyridyl nitrogen (2.261(8) Å). Also of note is that because of the steric interactions of the aryl hydrogens on C(17) and C(21) with the Au(1)-Cl(2) bond, two enantiomeric conformations of 11 (with the aryl hydrogen above and below the Cl(1)-Au(1)-Cl(2) plane) crystallized in the asymmetric unit.

Figure 4.

ORTEP diagram of 11. Ellipsoids shown at the 50 % level. Selected bond lengths (Å): Au(1)-N(1) 1.965(17), Au(1)-N(2) 2.080(14), Au(1)-Cl(2) 2.261(8), Au(1)-Cl(1) 2.280(8). Selected bond angles (°): N(1)-Au(1)-N(2) 83.0(6), N(1)-Au(1)-Cl(2) 171.2(5), N(2)-Au(1)-Cl(2) 94.1(5), N(1)-Au(1)-Cl(1) 95.1(5), N(2)-Au(1)-Cl(1) 176.9(5), Cl(2)-Au(1)-Cl(1) 87.5(4), N(2)-C(6)-C(5) 113(2), N(1)-C(5)-C(6) 115.2(18).

|

(7) |

With amido complex 11 in hand, we were able to prepare the dimethyl analogue 12 in moderate yields by transmetallation with SnMe4 (eq 7).[59] Two distinct methyl groups are observed in the 1HNMR spectrum at δ 1.00 and 0.79 in CDCl3, as would be required for a non-fluxional square-planar complex. The X-ray structure (Figure 5) reveals that the Au-CH3 bond trans to the anionic ligand has a bond length of 2.135(6) Å and is longer than Au-CH3 bond trans to the pyridyl nitrogen (2.051(9) Å). Additionally, the bond between gold and the pyrrolyl nitrogen is shorter than that between gold and the pyridyl nitrogen (2.064(7) vs 2.149(7) Å), reflecting the fact that gold forms a stronger bond with the anionic donor. As with the dichloride complex 11, two enantiomeric conformations of 12 were observed in the unit cell, suggesting hindered rotation around the C17-C18 bond (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

ORTEP diagram of 12. Ellipsoids shown at the 50 % level. Selected bond lengths (Å): Au(1)-C(2) 2.051(9), Au(1)-N(2) 2.064(7), Au(1)-C(1) 2.135(6), Au(1)-N(1) 2.149(7), N(1)-C(7) 1.346(11), N(1)-C(3) 1.347(11), N(2)-C(17) 1.372(10), N(2)-C(8) 1.402(10). Selected bond angles (°): C(2)-Au(1)-N(2) 98.6(3), C(2)-Au(1)-C(1) 87.1(4), N(2)-Au(1)-C(1) 174.2(3), C(2)-Au(1)-N(1) 173.4(4), N(2)-Au(1)-N(1) 77.6(3), C(1)-Au(1)-N(1) 96.8(3), N(2)-C(8)-C(7) 114.9(7).

Structurally, the dimethyl complex 12 is an excellent model of the isoelectronic pyridylindole platinum 13, which is capable of oxidatively adding the C-H bonds of benzene.[60] Complex 12 is also an exceedingly stable organometallic complex of gold, and can even be purified by column chromatography under aerobic conditions. Moreover, it is thermally robust, showing little decomposition (relative to an internal standard) by NMR spectroscopy after heating for one hour at 100° C in THF-d8 in a sealed tube. This thermal stability is in sharp contrast to that displayed by (PR3)AuXMe2 complexes, which show rapid loss of ethane at temperatures ranging from 45-75 °C, depending on the nature of X- and the nature of the phosphine ligand.[41-43] Complex 3 (R = Me) also loses ethane at lower temperatures (70 °C).[61] We speculate that the rigidity of the 2-(3,5-diphenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine ligand in 12 inhibits the dissociation of the pyridyl arm and the formation of a three-coordinate intermediate, making 12 resistant to reductive elimination reactions. This enhanced stability, however, is not desirable for the catalysis outlined in Scheme 1, as all attempts to effect Negishi, Kumada, Sonogashira, and Stille cross-couplings with alkyl iodides and bromides failed. Dimethyl gold(III) amido complexes based on the ligands 6 and 7 are anticipated to be much more coordinatively labile than those derived from 8, but synthetic methods to prepare these derivatives still need to be developed.

Concluding Remarks

While a number of studies on the reductive elimination of alkane from gold dialkyl complexes have been reported, relatively little is known about the organometallic chemistry of gold amido complexes. The synthetic methods reported herein allow for the generation of a structurally rigid bidentate amido dimethyl complex of gold and an initial study of its thermal stability. It is tempting to suggest that the elevated thermal stability of 12 is indicative of the fact that reductive elimination of ethane for pyridyl amido complexes of gold follows the same mechanism for (PR3)AuMe2X complexes and requires initial dissociation of a ligand to form a three-coordinate Au(III) intermediate. However, only when further studies on 12 are performed along with studies on a series of related pyridyl amido complexes will the mechanism of reductive elimination for this class of gold amido complexes be fully understood. Towards that endeavor, two amino pyridyl complexes of gold containing more floppy linkers has also been outlined in this report. The initial studies indicate that during the preparation gold complexes containing ligands 6 and 7, the formation of salts containing AuCl4 counter-ions must be avoided in order to both increase yields of gold amino complexes and to provide more versatile precursors to their respective amido derivatives.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

All manipulations were performed using standard Schlenk techniques or in a nitrogen-filled glovebox, unless otherwise noted. Solvents were distilled from appropriate drying agents before use, and deionized water was used for aqueous reactions. All reagents were used as received from commercial vendors unless otherwise noted. Elemental analyses were performed by Desert Analytics. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at ambient temperature on a JEOL 270 MHz and a Bruker 300 MHz spectrometer and referenced to residual proton solvent peaks. A Rigaku MSC Mercury/AFC8 diffractometer was used for X-ray structural determinations. The ligands N-isopropyl-N-2-methylpyridine,[62] N-isopropyl-N-2-ethylpyridine,[63] and 2-(3,5-diphenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine [64] were prepared by previously published methods.

Preparation of complex 9

A solution of N-isopropyl-N-2-methylpyridine (0.041g, 0.275 mmol) in degassed water (5 ml) was adjusted to pH 6 by addition of dilute hydrochloric acid solution and then added dropwise to a stirred solution of KAuCl4 hydrate (0.104g, 0.275 mmol) in degassed water (5 ml). A yellow solid precipitated immediately. After 50 minutes the solid was filtered and washed with water. A bright yellow solid was recovered and dried over vacuum (0.102g, 49%). 1H NMR (CD3CN, 270 MHz, 300K): δ 9.14 (dd, J = 6.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (dt, J = 7.9, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (dt, J = 6.9, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 5.05 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 4.73 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (septet, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 1.32 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (CD3CN, 300 MHz, 300 K): δ 147.1, 145.2, 126.9, 124.4, 59.3, 57.2, 29.9. Anal. Calcd for C9H14Au2Cl6N2: C 14.28, H 1.86. Found: C 14.59, H 1.83.

Preparation of complex 10

To an aqueous solution of NaAuCl4.2H2O (0.200g, 0.503mmol) was added 5.03ml of a 0.1 M water solution of N-isopropyl-N-2-ethylpyridine (0.082g, 0.503 mmol). A yellow solid precipitated immediately and was filtered and washed with water. The solid was then recrystallized via vapor diffusion from acetonitrile with diethyl ether to give bright yellow crystals (0.093g, 24%). 1H NMR (CD3CN, 300 MHz, 300K): δ 9.01 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (dt, J = 7.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (dt, J = 6.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (dsept, J = 6.8, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.55(m, 2H), 3.3-3.2 (m, 1H), 2.87-2.75 (m, 1H), 1.22 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.23 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H). 13CNMR (CD3CN, 300MHz, 300K): δ 150.5, 145.2, 128.8, 126.5, 59.5, 41.4, 38.9, 20.3, 19.3. Anal. Calcd for C10H16Au2Cl6N2: C 15.58, H 2.09. Found: C 15.81, H 2.36.

Preparation of complex 11

To a solution of NaAuCl4.2H2O (0.113 g, 0.284 mmol) in 6 mL of degassed water was added a solution of 2-(3,5-diphenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine (0.084 g, 0.284 mmol) in 3 mL of acetonitrile. The mixture became cloudy and then a brown precipitate was formed. The mixture was allowed to stir overnight at room temperature. After filtration a brown solid was recovered (0.148 g, 92%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 270 MHz, 300K): δ 9.02 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.45 (m, 5H), 7.35 (m, 4H), 6.99 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (s, 1H). Anal. Calcd. for C21H15AuCl2N2: C 44.78, H 2.68. Found: C 44.98, H 2.84.

Preparation of complex 12

SnMe4 (0.049mL, 0.355mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of 11 (0.100 g, 0.177 mmol) in 5 mL of distilled THF at -78 °C. The mixture was stirred at low temperature during 15 min, then at room temperature for 1.5 h. Then the solution was refluxed for 4 h. The solution turned from dark brown to light orange with a brown deposit in the flask. Solvents were removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under vacuum. After purification by chromatography (hexane/ AcOEt), a yellow product is recovered (0.045g, 49%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 270 MHz, 300K): δ 8.22 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.60-7.24 (m, 12H), 6.93 (m, 1H), 6.43 (s, 1H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.79 (s, 3H). Anal. Calcd. for C23H21AuN2: C 52.88, H 4.05. Found: C 52.77, H 4.24.

Crystallographic analyses of all new compounds

The crystal data are shown in Table 1. Data were collected on a Rigaku/MSC AFC8 Mercury CCD diffractometer using Mo Kα radiation. The structures were solved by direct methods using SHELXS-97 [65] and refined by full-matrix least-squares procedures on Fo2 using SHELXL-97.[66] All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. The hydrogen atom positions have been refined using the atom corresponding riding model.

Table 1.

Crystal Data and structure refinement parameters for all new compounds.

| Compound | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chemical formula | C9H14Au2Cl6N2 | C10H16Au2Cl6N2 | C21H15AuCl2N2 | C23H21AuN2 |

| formula weight | 756.86 | 770.88 | 563.22 | 522.38 |

| crystal dimensions (mm) | 0.45 × 0.40 × 0.25 | 0.30 × 0.20 × 0.10 | 0.4 × 0.2 × 0.2 | 0.30 × 0.20 × 0.10 |

| color, habit | gold, prism | gold, prism | gold, prism | gold, prism |

| crystal system | triclinic | triclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| wavelength, Å | 0.71070 | 0.71070 | 0.71070 | 0.71070 |

| μ (cm-1) | 17.563 | 17.089 | 7.985 | 7.739 |

| space group, Z | P-1, 2 | P-1, 2 | P21, 4 | P21/n, 4 |

| a, Å | 7.912(14) | 8.149(9) | 6.5109(15) | 12.379(3) |

| b, Å | 10.141(16) | 10.06(3) | 15.618(4) | 9.617(2) |

| c, Å | 11.17(3) | 11.732(17) | 18.865(6) | 15.986(4) |

| α (deg) | 92.62(6) | 8.149(9) | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 97.75(6) | 10.06(3) | 95.026(7) | 90.594(6) |

| γ (deg) | 97.16(6) | 11.732(17) | 90 | 90 |

| vol, Å3 | 879(3) | 904(3) | 1910.9(9) | 1903.0(8) |

| ρcalc, g cm-1 | 2.858 | 2.832 | 1.958 | 1.823 |

| temp, deg C | -100 | -100 | 25 | -100 |

| R indices [I>2sigma(I)] | 0.0397, 0.0948 | 0.0328, 0.0849 | 0.0459, 0.1018 | 0.0590, 0.1302 |

| R indices [all data] | 0.0457, 0.0970 | 0.0378, 0.0872 | 0.0622, 0.1139 | 0.0761, 0.1441 |

| goodness of fit | 1.037 | 1.105 | 1.066 | 1.125 |

| θ range, deg | 1.84 – 27.99 | 1.79 – 28.0 | 2.53 - 28.00 | 2.07 – 28.00 |

| number of data collected | 17972 | 18568 | 19143 | 19051 |

| number of unique data | 4247 | 4367 | 7294 | 4593 |

| Rint | 0.0866 | 0.0523 | 0.0556 | 0.0707 |

Acknowledgments

D.A.V. thanks the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, of the U. S. Department of Energy (DE-FG02-06ER15801), the Arkansas Biosciences Institute, and the NIH (RR-015569-06) for support of this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data. Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) for compounds 9-12 have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as supplementary publication numbers CCDC 617336 – 617339, respectively. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK [fax: +44 1223 336 033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk].

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hashmi ASK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:6990. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchings GJ. Catal Today. 2005;100:55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieuwenhuys BE, Gluhoi AC, Rienks EDL, Weststrate CJ, Vinod CP. Catal Today. 2005;100:49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanagisawa A. Modern Aldol Reactions. 2004;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann-Roeder A, Krause N. Organic & Biomolecular Chem. 2005;3:387. doi: 10.1039/b416516k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashmi ASK. Gold Bull. 2004;37:51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchings GJ. Gold Bull. 2004;37:3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arcadi A, Di Giuseppe S. Cur Org Chem. 2004;8:795. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchings G. Tce. 2004;753:34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyker G. Organic Synthesis Highlights V. 2003:48. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashmi ASK. Gold Bull. 2003;36:3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carabineiro S. Chemisch2Weekblad. 2002;98:12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bond GC. Catal Today. 2002;72:5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidbaur H. Gmelin Handbook of Inorganic Chemistry. Springer Verlag; Berlin: 1980. Organogold Compounds. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grohmann A, Schmidbaur H. Gold. In: Wilkinson G, Stone FGA, Abel EW, editors. Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry II. Pergamon; Oxford: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiotani A, Schmidbaur H. J Organomet Chem. 1972;37:C24–C26. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs G, Ricote S, Patterson PM, Graham UM, Dozier A, Khalid S, Rhodus E, Davis BH. Applied Catal A. 2005;292:229. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzman J, Fierro-Gonzalez JC, Aguilar-Guerrero V, Hao Y, Gates BC. Z Phys Chem. 2005:219–921. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fierro-Gonzalez JC, Anderson BG, Ramesh K, Vinod CP, Niemantsverdriet JW, Gates BC. Catal Lett. 2005;101:265. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fierro-Gonzalez JC, Gates BC. Langmuir. 2005;21:5693. doi: 10.1021/la0506574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fierro-Gonzalez JC, Gates BC. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:7275. doi: 10.1021/jp050318j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie G, Song M, Mitsuishi K, Furuya K. Applied Surface Sci. 2005;241:91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicoira F, Hoffmann P, Olsson COA, Xanthopoulos N, Mathieu HJ, Doppelt P. Applied Surface Sci. 2005;242:107. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fierro-Gonzalez JC, Gates BC. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:16999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzman J, Gates BC. J Catal. 2004;226:111. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabanas A, Long DP, Watkins JJ. Chem Mat. 2004;16:2028. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guzman J, Kuba S, Fierro-Gonzalez JC, Gates BC. Catal Lett. 2004;95:77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi C, Akita T, Okumura M, Kuraoka K, Haruta M. Applied Catal A. 2003;253:75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Croitoru MD, Hochst A, Bertsche G, Krauss S, Roth S, Kern DP. Microelectronic Eng. 2003;67-68:696. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okumura M, Tsubota S, Haruta M. J Mol Catal A. 2003;199:73. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guzman J, Gates BC. Langmuir. 2003;19:3897. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guzman J, Gates BC. Nano Lett. 2001;1:689. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okumura M, Haruta M. Chem Lett. 2000:396. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okumura M, Nakamura SI, Tsubota S, Nakamura T, Haruta M. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis. 1998;118:277. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okumura M, Tsubota S, Iwamoto M, Haruta M. Chem Lett. 1998:315. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brain FH, Gibson CS. J Chem Soc. 1939:762. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuster O, Liau RY, Schier A, Schmidbaur H. Inorg Chim Acta. 2005;358:1429. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komiya S, Sone T, Ozaki S, Ishikawa M, Kasuga N. J Organomet Chem. 1992;428:303. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puddephatt RJ, Treurnicht I. J Organomet Chem. 1987;319:129. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Komiya S, Ozaki S, Shibue A. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1986:1555. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komiya S, Shibue A. Organometallics. 1985;4:684. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuch PL, Tobias RS. J Organomet Chem. 1976;122:429. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komiya S, Kochi JK. J Amer Chem Soc. 1976;98:7599. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamaki A, Magennis SA, Kochi JK. J Amer Chem Soc. 1974;96:6140. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Komiya S, Albright TA, Hoffmann R, Kochi JK. J Amer Chem Soc. 1976;98:7255. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semyannikov PP, Zharkova GI, Grankin VM, Tyukalevskaya NM, Igumenov IK. Metalloorganicheskaya Khimiya. 1988;1:1105. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson TJ, Jones GD, Vicic DA. J Amer Chem Soc. 2004;126:8100. doi: 10.1021/ja0483903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones GD, McFarland C, Anderson TJ, Vicic DA. Chem Commun. 2005:4211. doi: 10.1039/b504996b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hadei N, Kantchev EAB, O'Brien CJ, Organ MG. Org Lett. 2005;7:3805. doi: 10.1021/ol0514909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou J, Fu GC. J Amer Chem Soc. 2003;125:14726. doi: 10.1021/ja0389366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Netherton MR, Fu GC. Adv Syn Catal. 2004;346:1525. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen AE, Knochel P. J Org Chem. 2002;67:79. doi: 10.1021/jo0105787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arp FO, Fu GC. J Amer Chem Soc. 2005;127:10482. doi: 10.1021/ja053751f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuerstner A, Martin R. Chem Lett. 2005;34:624. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamaki A, Kochi JK. J Organomet Chem. 1972;40:C81. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson A, Puddephatt RJ. J Organomet Chem. 1975;85:115. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tamaki A, Kochi JK. J Organomet Chem. 1974;64:411. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson A, Puddephatt RJ. Inorg Nuclear Chem Lett. 1973;9:1175. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paul M, Schmidbaur H, Naturforsch Z. B: Chem Sci. 1994;49:647. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karshtedt D, McBee JL, Bell AT, Tilley TD. Organometallics. 2006;25:1801. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klassen RB, Baum TH. Organometallics. 1989;8:2477. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spencer DJE, Johnson BJ, Johnson BJ, Tolman WB. Org Lett. 2002;4:1391. doi: 10.1021/ol025715g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crabb TA, Newton RF. Tetrahedron. 1970;26:701. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klappa JJ, Rich AE, McNeill K. Org Lett. 2002;4:435. doi: 10.1021/ol017147v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr Sect A. 1990;46:467. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sheldrick GM. SHELXS-97 (Release 97-2) University of Göttingen; Germany: 1997. [Google Scholar]