Abstract

Historically, girls have been less delinquent than boys. However, increased justice system involvement among girls and current portrayals of girls in the popular media and press suggest that girls’ delinquency, particularly their violence and drug use, is becoming more similar to that of boys. Are girls really becoming more delinquent? To date, this question remains unresolved. Girls’ increased system involvement might reflect actual changes in their behavior or changes in justice system policies and practices. Given that girls of color are overrepresented in the justice system, efforts to rigorously examine the gender convergence hypothesis must consider the role of race/ethnicity in girls’ delinquency. This study uses self-report data from a large, nationally representative sample of youth to investigate the extent to which the magnitude of gender differences in violence and substance use varies across racial/ethnic groups and explore whether these differences have decreased over time. We find little support for the gender convergence hypothesis, because, with a few exceptions, the data do not show increases in girls’ violence or drug use. Furthermore, even when girls’ violent behavior or drug use has increased, the magnitude of the increase is not substantial enough to account for the dramatic increases in girls’ arrests for violence and drug abuse violations.

Historically, girls have been less likely than boys to engage in delinquent behavior. Current portrayals of girls in the popular media and press, however, suggest that girls’ delinquency, particularly their violence and drug use, is on the rise. Recent examples of these portrayals include titles such as, “Bad girls go wild” (Scelfo, 2005), See Jane Hit: Why Girls are Growing More Violent and What Can Be Done About It (Garbarino, 2006) and Sugar & Spice and No Longer Nice: How We Can Stop Girls’ Violence (Prothrow-Stith & Spivak, 2005). These and related publications suggest that girls’ behavior is becoming more similar to that of boys and that this convergence can be attributed, in large part, to socialization practices that increasingly encourage girls to be more like boys in both positive and negative arenas of social life. Coupled with substantial increases in girls’ arrests and adjudications for violent crimes and drug abuse violations over the past 25 years (Snyder & Sigmund, 2006), these works convey an image of girls’ behavior as getting worse and suggest the need for interventions targeted toward the increasingly problematic behavior of young women.

Despite the prevalence of this image in discourses about young women, the question of whether girls are really becoming more delinquent remains unresolved. A number of recent studies have begun to examine claims about the increasingly violent behavior of young women (e.g., Chesney-Lind & Paramore, 2001; Steffensmeier et al., 2005). One of the most thorough investigations of this question examined whether the gender gap in violent behavior was closing among American young people (Steffensmeier et al., 2005). After comparing arrest statistics with victimization data and self-reports, the authors concluded that although girls’ violent behavior has not changed, society’s response to their violent behavior has changed significantly. The authors attribute the increase in girls’ arrests for violent behavior to the following three factors: 1) broadening definitions of violence to include minor incidents, which girls are relatively more likely to commit; 2) “increased policing of violence among intimates and in private settings (for example, home, school) where girls’ violence is more widespread” (2005, p. 355); and 3) decreased tolerance within families and in society more broadly towards adolescent girls.

Although Steffensmeier and colleagues’ results suggest that girls have not become more delinquent, they note that their findings “do not negate the possibility of gender convergence in violence trends within some population subgroups” (Steffensmeier et al., 2005, p. 392). More specifically, their work raises the question of whether the magnitude of gender difference in delinquency varies across racial/ethnic groups, with trends in boys’ and girls’ delinquency being more comparable for some groups than for others. Many of the images that accompany recent books and articles have focused primarily on White girls (see, for example, the covers of the Garbarino [2006] and Prothrow-Stith and Spivak [2005] books). Yet, girls of color, particularly African American girls, are disproportionately represented among those in the juvenile justice system, a problem that has increased over time. For example, African American girls accounted for 23% of girls’ delinquency cases in 1985 and 31% of such cases by 2004 (when African Americans comprised only 17% of the juvenile population; OJJDP, 2007). The overrepresentation of African American girls in the juvenile justice statistics suggests that there may be different patterns of delinquent behavior by racial/ethnic group, or that the behavior of members of different racial/ethnic groups is handled differently by police and justice system authorities.

Are there different patterns of delinquent behavior by African American girls and boys or girls and boys of other racial/ethnic groups? Research has not yet examined the gender convergence hypothesis within or between racial and ethnic groups. These questions are important for social workers and social service professionals because interventions are often shaped by how a particular problem is perceived or constructed. For example, images of girls as more violent and delinquent have, at least arguably, influenced the increasing tendency to arrest and adjudicate them in the justice systems. Yet, the mounting evidence that girls are not, in fact, becoming more delinquent suggests that trends toward increasing intervention through the justice systems might be misplaced. Furthermore, perceptions and policing of crime in the U.S. are racialized phenomena; yet there is little research in this area examining gender and race simultaneously. Thus, there is a need for research to examine these questions and provide rigorous empirical evidence so that interventions and programs can be targeted appropriately.

In an effort to advance knowledge on gender differences in delinquency, the present study uses large, nationally representative samples of racially and ethnically diverse American young people to examine the gender convergence hypothesis. We use self-report data from the Monitoring the Future study to assess the magnitude of gender differences in violence and substance use, to investigate the extent to which the magnitude of gender differences in violence and substance use varies across racial/ethnic groups, and to determine whether these differences have or have not decreased over time.

Literature Review

A Closer Look at Arrest Data

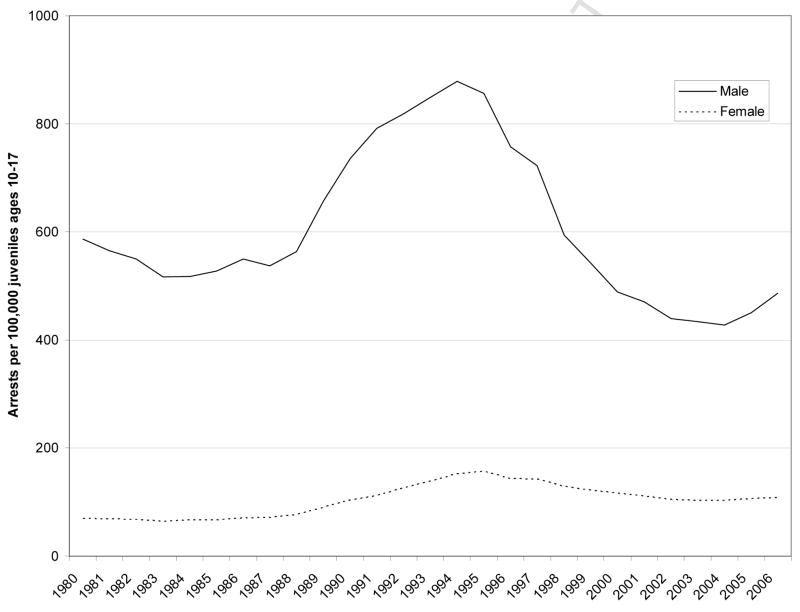

Increases in girls’ arrests for violent offenses and drug abuse violations have been used to support the convergence hypothesis. However, a closer examination of arrest data reveals problems with using these statistics in support of the convergence hypothesis – in large part because boys’ arrests have increased so much, in many cases more than girls’. Looking first at violence, we find that girls do account for a greater percentage of juvenile violent crime index1 arrests than they did in the past – up from about 10% in 1980 to 17% in 2006, a trend which is driven largely by increased arrests of girls for aggravated assault (Snyder & Sigmund, 2006; Snyder, forthcoming). However, an examination of violent crime index arrest rate trends by gender (Figure 1) reveals that the increase in girls’ arrests for violent crimes in the early 1990s was concomitant with a much larger increase in boys’ arrests during the same period, thus exhibiting gender divergence at that time.2 Further, Figure 1 demonstrates that the recent convergence in girls’ and boys’ arrests for violent crimes reflects the fact that boys’ rates of arrest have been dropping more sharply than those of girls.

Figure 1.

Violent Crime Index Arrest Rate Trends

Data Source:National Center Juvenile Justice. (2007). Juvenile Offense Rates by Offense, Sex, and Race.

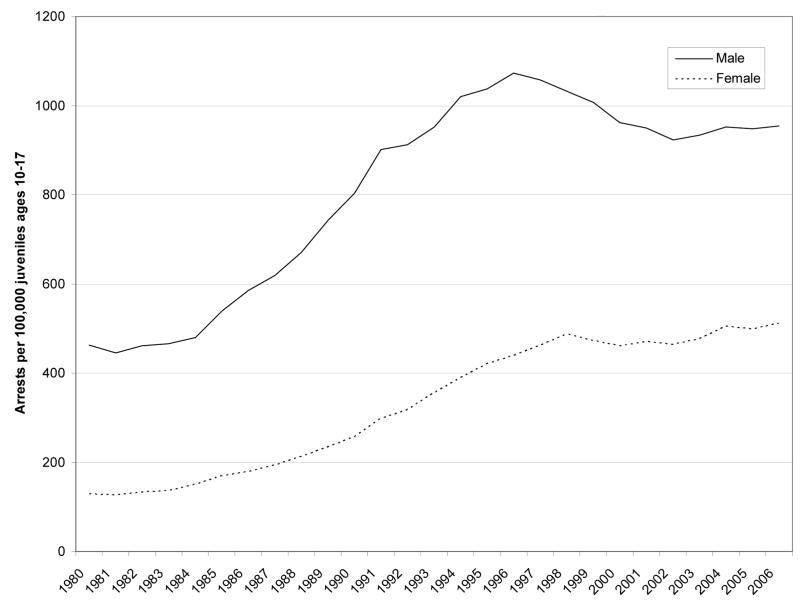

The story for simple assault (which is not included in the violent crime index) is a little different. The data suggest that girls’ arrests rates increased 395% (from 130 to 513 arrests per 100,000 girls aged 10–17) between 1980 and 2006 (National Center for Juvenile Justice, 2007). As Figure 2 shows, girls’ arrest rates for simple assault rose until 1998, then fell slightly and have recently increased again. Boys’ arrest rates for simple assault peaked in 1996 and have fallen slightly since (although like those of girls, boys’ arrest rates have risen slightly since 2004). Nevertheless, the absolute difference between girls’ and boys’ rates remains larger now than it was during the early 1980s, because boys’ rates of arrest for simple assault increased much more than did those of girls from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. As Steffensmeier and colleagues (2005) noted, broadening definitions of violence have increased arrests of both boys and girls for simple assault. In addition, as they and many others (e.g., Chesney-Lind, 2002) have suggested, increased policing of violence between intimates also accounts for the increase, especially in girls’ rates. For example, domestic violence mandatory arrest policies have led to increased arrests of girls for assault, when in the past they might have been charged with incorrigibility or not arrested at all (Chesney-Lind, 2002).

Figure 2.

Simple Assault Arrest Rate Trends

Data Source:National Center Juvenile Justice. (2007). Juvenile Offense Rates by Offense, Sex, and Race.

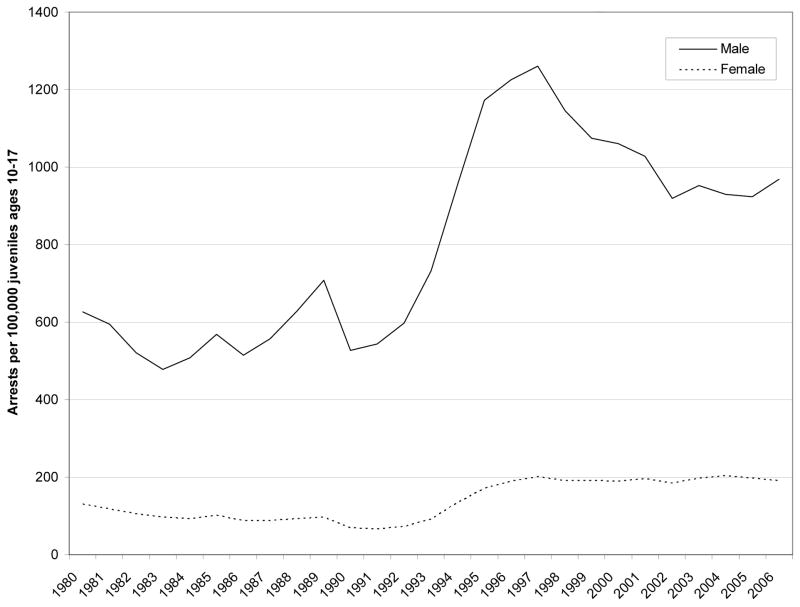

Similarly, although girls’ drug abuse violation arrests have increased over time, the data reveal more of a gender divergence than convergence, particularly in the 1990s when boys’ arrests increased much more than those of girls (see Figure 3). The modest gender convergence in the past ten years results largely from the decline in boys’ arrests, while girls’ arrests over this period have remained stable (see Snyder & Sigmund, 2006; National Center for Juvenile Justice, 2007).

Figure 3.

Drug Abuse Violation Arrest Rate Trends

Data Source:National Center Juvenile Justice. (2007). Juvenile Offense Rates by Offense, Sex, and Race.

In sum, arrest data show that while girls are being arrested more often today than they were 25 years ago for violence and drug abuse violations, so are boys. Thus, even arrest data reveal very little convergence in the behavior of girls and boys, although they do suggest that perhaps both girls and boys have become more delinquent. However, as discussed in the next section, there are other plausible explanations for the increases in girls’ (and boys’) arrests.

Theoretical Explanations for Increased Arrests

In light of the relative absence of gender convergence in arrests for violence and substance abuse, why is there the public perception that, relative to boys, girls have become more delinquent? Luke (2008) cites two main explanations frequently proffered for conclusions that girls’ violence (and perhaps other delinquent behavior) has increased: 1) U.S. society has become increasingly violent; and, 2) feminism has brought greater freedom to girls and women, which has enabled them to participate in the “male” domains of violence and crime. There is little empirical evidence to support the former claim, despite the fact that both girls’ and boys’ arrests for assault have increased. In fact, the National Crime Victimization Survey shows a dramatic decrease in violence over the last several decades, as rates of violent victimization in the general population have fallen from just under 50 per 1,000 to approximately 20 per 1,000 from 1973 to 2005 (Catalano, 2006; Rand, Lynch, & Cantor, 1997). Most of this decrease has occurred over the last decade when rates of violent victimization among youth aged 12–19 decreased by more than 50%.3 The latter explanation – that the increase in girls’ violence is a result of feminism – has been addressed in the literature, which has generally concluded that the liberation theory of delinquency and crime (as it is sometimes called) stems from a backlash against feminism rather than from empirical evidence to support it (Carrington, 2006; Smart, 1976; Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996).

The current conventional wisdom represents a more nuanced form of liberation theory as an explanation for girls’ increased violence. For example, both Garbarino (2006) and Prothrow-Stith and Spivak (2005) argue that girls are being socialized more like boys (for example increasingly participating in rough, physical sports), which then leads to their increased delinquency. Nevertheless, the empirical evidence suggests that girls’ violence overall is not on the rise (see, e.g., Steffensmeier et al., 2005; although, as previously noted, there has been no broad empirical examination of trends in girls’ violence and delinquency by race/ethnicity).

So what can we make of portrayals of girls as increasingly delinquent? Many of those portraying girls this way are trying to understand girls’ increased arrests and involvement with the justice system. Unfortunately, most take a normative perspective, accepting the fact of increased arrests and system involvement as evidence of a change in behavior, and then trying to find explanations for this behavioral change. Alternatively, a constructivist approach takes a step back and examines what the normative approach takes as given, that girls’ behavior has, in fact, changed. Such an approach asks whether the increase in arrests and justice system involvement among girls is a reflection of actual changes in girls’ behavior or of changes in how society responds to girls’ behavior. Self-reports do not completely resolve this issue, because, as we discuss subsequently, social norms about the desirability of answering certain questions about violent behavior may have changed; nevertheless, self-reports do provide a way around the sole reliance on arrest data, which can be driven by changes in policing and reporting practices.

Similarly, the constructivist perspective is useful for considering racial/ethnic differences in justice system involvement. In other words, girls of color may actually be more likely than White girls to be violent and use substances, or their behavior may not be that different but they may simply be more likely to be arrested and adjudicated for these behaviors. Thus, a constructivist perspective necessitates that we think critically about the overrepresentation of girls of color in the justice system. As noted previously, media portrayals of the recent concern with the supposed increase in violence and delinquency of girls often feature images of White girls, thus suggesting that the story is not just one of gender, but rather of the complicated ways that gender and race interact. Luke (2008) argues that “the gendered division of violent behavior has been more rigidly enforced among white girls than among girls of color. …Black girls in the United States…have been constructed by mainstream society as not really girls” (p. 45). Thus, mainstream gendered expectations are not threatened by African American girls’ involvement with the justice system, as behaving in “masculine” ways is a part of dominant cultural constructions of African American girls (Collins, 1998). However, rising rates of system involvement among White girls present a challenge to normative ideas about gender and gendered behavior, based on cultural constructions of White girls as gentle and passive. Recent concern with girls’ behavior, by featuring pictures of White girls, suggests that White girls’ delinquency, in particular, is on the rise and that for young people of other racial/ethnic groups there may already have been a greater gender convergence in delinquent behavior. In this study, we examine these suppositions empirically, testing the gender convergence hypothesis by race/ethnicity.

Methods

This study examines the gender convergence hypothesis and explores possible explanations for the increase in girls’ arrests for violence and drug abuse violations using self-report data to examine patterns and trends of delinquency among America’s increasingly racially and ethnically diverse population. Our analyses reflect this diversity by comparing girls and boys by racial/ethnic subgroup, including African Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, and Whites.

Sample

The data for this investigation were drawn from the University of Michigan’s Monitoring the Future study. The study design and methods are summarized briefly here; a detailed description is available elsewhere (see Bachman, Johnston, O’Malley, & Schulenberg, 2006; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2006). Monitoring the Future uses a multi-stage sampling procedure to obtain nationally representative samples of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders from the 48 contiguous states. Stage one is the selection of geographic region; stage two is the selection of specific schools – approximately 420 each year; and stage three is the selection of students within each school. This sampling strategy has been used to collect data annually from high school seniors since 1975 and from 8th and 10th graders since 1991. Sample weights are assigned to each student to take into account differential probabilities of selection. In order to examine changes over the greatest period of time, data are shown for 12th graders.4

Students’ data are collected via self-completed machine-readable questionnaires, usually administered during normal class periods. Questionnaire response rates average 86%. Absence on the day of data collection was the primary reason that students were missed; it is estimated that less than one percent of students refused to complete the questionnaire. Multiple questionnaire forms, randomly distributed within classrooms, are used to allow for greater content coverage. The questions about substance use are on all forms, but the questions on violent behavior are included in only one of four forms in 8th and 10th grades and one of five or six forms in 12th grade.

Monitoring the Future was designed to provide data representative of the nation as a whole, not data on racial/ethnic or gender differences. Accordingly, no special effort was made to over-sample students in any of the subgroups. Because a number of the racial/ethnic subgroups examined here are a relatively small proportion of the total population, their numbers in the annual samples are also relatively small. Therefore, in an effort to increase the numbers of cases for analysis, we combined data into six 5-year intervals from 1976 to 2005. Thus, current prevalence figures include data from 2001 to 2005, and trend analyses include data from 1976–1980, 1981–1985, 1986–1990, 1991–95, 1996–2000, and 2001–2005. The combined samples include data from approximately 59,653 12th graders for the most recent data period. Table 1 presents the numbers by gender and race/ethnicity for the 2001–2005 period combined.5

Table 1.

Approximate Weighted Ns by Gender and Race/ethnicity (2001–2005 combined)

| Race/ethnicity | Girls | Boys | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 22,646 | 19,431 | 42,077 |

| African American | 4,286 | 2,701 | 6,987 |

| Hispanic | 3,995 | 3,265 | 7,260 |

| Asian American | 1,502 | 1,273 | 2,775 |

| Native American | 288 | 266 | 554 |

| Total | 32,717 | 26,936 | 59,653 |

Measures

Race/ethnicity is measured by the following question: “How do you describe yourself?” The various response categories are used to provide the following categorization in analyses: 1 = White or Caucasian, 2 = Black or African American, 3 = Hispanic, 4 = Asian American, and 5 = Native American.6 The gender measure is worded, “What is your sex?” with response categories 1 = male, 2 = female.

We employ two measures of violent behavior.7 The first, which we call “fighting,” includes dichotomized responses to the question, “During the last 12 months, how often have you gotten into a serious fight at school or at work?” The second, which we refer to as “injuring someone,” is based on the following question, “During the last 12 months, how often have you hurt someone badly enough to need bandages or a doctor?” In the results section we present data on the percentage of students who report that they have had one or more serious fights in the last year and the percent who report that they have hurt someone badly enough to need medical attention in the last year.

We also use two measures of substance use. The first focuses on the use of alcohol, and included dichotomized responses to the following question: “On how many occasions have you had alcoholic beverages to drink – more than just a few sips – during the last 30 days?” The second assesses the use of marijuana with dichotomized responses to the question, “On how many occasions (if any) have you used marijuana (weed, pot) or hashish (hash, hash oil) during the last 12 months?” The analyses present data on the percent of students who report that they have used alcohol in the last 30 days and who have used marijuana in the last 12 months.

Analysis Strategy

We first examine gender differences in violence and substance use by comparing the current prevalence (2001–2005 data combined), for girls and boys by race/ethnicity, presenting the ratio of the gender difference to gauge the extent to which the magnitude of the gender gap varies across the racial/ethnic subgroups (see Table 2). Next, we present trend data on the gender differences in violence and substance use from 1976 to 2005, to examine explicitly the gender convergence hypothesis, by race/ethnicity.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Fighting, Injuring Someone, Alcohol Use, and Marijuana Use by Gender and Race/ethnicity (2001–2005 combined)

| Fighting | Injuring Someone | Alcohol Use | Marijuana Use | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | Boys | Girls | Ratio | Boys | Girls | Ratio | Boys | Girls | Ratio | Boys | Girls | Ratio |

| White | 14.6 | 9.3 | 1.6 | 17.2 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 56.1 | 49.8 | 1.1 | 40.1 | 35.1 | 1.1 |

| African American | 21.9 | 15.9 | 1.4 | 24.4 | 9.7 | 2.5 | 35.1 | 25.5 | 1.4 | 35.0 | 21.0 | 1.7 |

| Hispanic | 25.1 | 11.8 | 2.1 | 20.4 | 7.6 | 2.7 | 48.8 | 42.6 | 1.1 | 35.7 | 27.7 | 1.3 |

| Asian American | 14.8 | 5.8 | 2.6 | 13.8 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 34.8 | 27.3 | 1.3 | 23.4 | 15.7 | 1.5 |

| Native American | 21.2 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 28.9 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 49.0 | 43.5 | 1.1 | 45.0 | 38.6 | 1.2 |

Note: The largest 95% confidence intervals around percentages are 3.6% for Whites, 6.2% for African Americans, 5.6% for Hispanics, 8.0% for Asian Americans, and 17.2% for Native Americans.

Results

Current Prevalence

Violence

Table 2 presents the current prevalence of the selected measures of delinquent behavior. Looking first at fighting, boys are generally more likely than girls to report engaging in fighting, both in the overall sample and within each racial and ethnic subgroup.8 However, African American girls are about as likely to report fighting as White or Asian American boys. The third column of data for each of the delinquency measures is the ratio of girls’ to boys’ involvement in each of the behaviors. These ratios provide some sense of the relative magnitude of the gender difference within and between the racial/ethnic subgroups. The closer the ratios are to a value of 1, the more similar boys’ and girls’ behavior, and the further the value is from 1, the larger the gender gap. Gender differences are larger among Hispanic, Asian American, and Native American youth than among African American and White youth. This, in part, reflects different racial/ethnic patterns, by gender, in that among girls, the highest rates of fighting are reported by African Americans, followed by Hispanics, Whites, and then by Asian Americans and Native Americans. Among boys, however, the highest rates of fighting are reported by Hispanics and African Americans, followed by Native Americans, Whites, and Asian Americans.

The results are somewhat different when we turn to the current prevalence of injuring someone. Most striking, perhaps, is the magnitude of gender difference, which is generally much more pronounced for injuring someone than for fighting. For boys, rates of fighting and injuring someone by racial/ethnic group are very similar, (e.g., 15% of White boys report fighting and 17% report injuring someone). In fact, White, African American, and Native American boys report higher rates of injuring someone than of fighting.9 For girls, however, the results are quite different. With the exception of Native American girls, girls report injuring someone at rates significantly lower than they report engaging in fighting, which helps to explain the greater magnitude of gender differences found for injuring someone.

Further, it should be noted that the rates of injuring someone for every group of boys are higher than for any group of girls, whereas African American girls reported fighting at rates similar to those of White or Asian American boys. Racial/ethnic patterns are more similar for the two genders with regard to injuring someone, except that Native American girls seem less likely than African American or Hispanic girls to report injuring someone, whereas Native American boys seem the most likely of any group of boys to report having done so.10 We see the least gender difference in self-reports of injuring someone among African American and Hispanic youth, followed by White, Native American, and Asian American youth.

Substance use

With regard to substance use, the results are quite different. In terms of alcohol use, we see relatively little gender difference, both overall and by racial/ethnic group, with girls in each group reporting alcohol use at levels just below those of boys (with the largest gender differences for African American and Asian American youth). There is greater variation by race/ethnicity, with Whites reporting the highest levels of alcohol use, followed by Native Americans and Hispanics, and then by Asian Americans and African Americans.11 Thus, White girls engage in alcohol use at rates equal to or higher than those of any group of boys (with the exception of White boys), while African American and Asian American girls have the lowest rates of alcohol use of any group included here.

Similarly, for marijuana use, there is relatively little gender difference, with girls’ rates generally being slightly lower than those of boys in their racial/ethnic group and the greatest gender difference reported by African Americans (followed by Asian Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Whites). In this case, Native Americans and Whites report the highest levels of marijuana use, followed by Hispanics and African Americans, and then by Asian Americans. Notably, White girls use marijuana at rates similar to those of African American and Hispanic boys, and higher than those of African American, Hispanic, or Asian American girls.

Thus, in terms of current behaviors, we find the greatest gender divergence in measures of violence, specifically for injuring someone and with regard to fighting to a somewhat lesser extent. Rates of substance use differ by gender to a much lesser extent, with some significant differences by race/ethnicity. While African American youth show the greatest gender convergence of any racial/ethnic group in measures of violence, they are the most divergent in measures of substance use.

Trends over Time

Violence

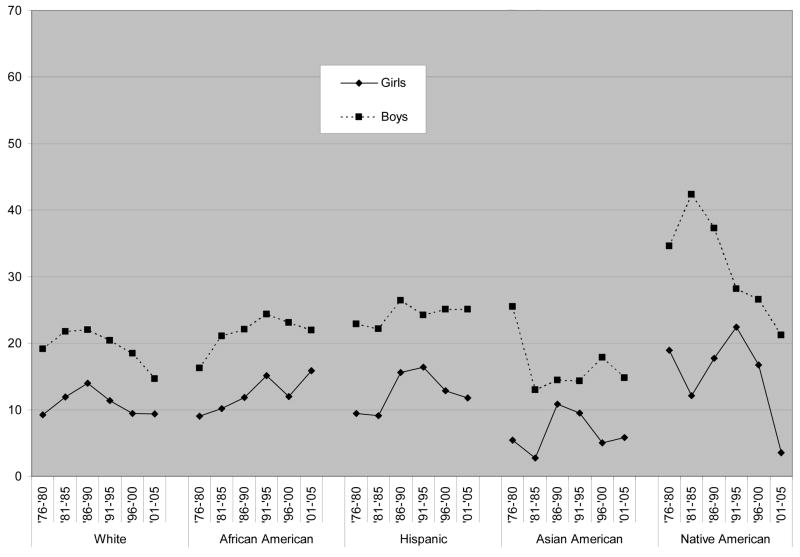

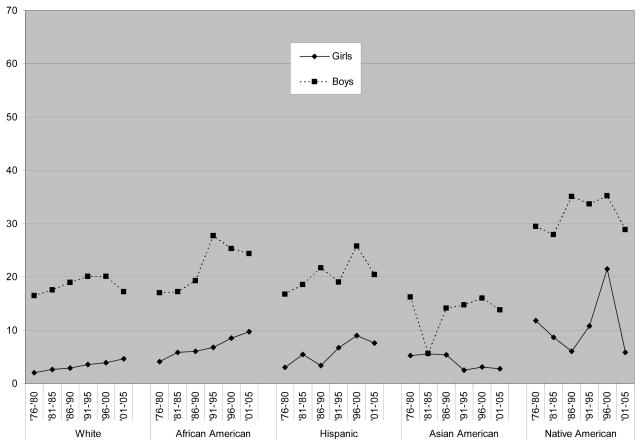

The following set of figures allows us to examine gender convergence over time. Figure 4 presents gender comparisons over time in rates of fighting.12 The first point to note is that White girls’ reported rates of fighting in the most recent period are almost exactly the same as they were during the period of 1976–1980. White boys’ current rates of fighting, however, are actually lower in the most recent period than they were in 1976–1980. Both rates did increase somewhat between 1976–80 and 1986–90, but have been dropping since. Thus, we can conclude that the gender convergence we find between White girls and boys is due to a decrease in boys’ rates of fighting rather than an increase in those of girls.

Figure 4.

Fighting at school or work, trends over time (1976–2005)

The results are a little different, however, for African American youth. Rates of fighting for both African American girls and boys have increased somewhat over this period, although the increases occurred mainly between 1976–80 and 1991–95, with boys’ rates decreasing since then and girls’ rates decreasing and then increasing. Notably, the gender differential has not changed much over time, although the fact that, in the most recent period, boys’ rates have decreased and those of girls gone up does demonstrate a slight convergence.

For Hispanic youth, there was a slight gender convergence in rates of fighting during the late 1980s and early 1990s, due primarily to an increase in girls’ rates. However, girls’ rates have since decreased, almost returning to their levels in the late 1970s and early 1980s and boys’ rates have remained relatively unchanged. Thus, the past 10 years have demonstrated a gender divergence for Hispanic youth. The results for Asian American youth are similar – a gender convergence in the late 1980s and early 1990s, then a divergence in the late 1990s as girls’ rates decreased and those of boys went up, with a slight leveling off of this trend in the most recent time period. Most notable is the fact that although Asian American girls’ rates of fighting increased in the late 1980s, they have since returned to approximately the same rates as reported by Asian American girls in the late 1970s. Finally, when we look at the patterns for Native American youth, the most striking finding is that the rates for both girls and boys have recently decreased dramatically. While we interpret these findings with caution, due to the small number of Native American youth sampled, the gender convergence of the early 1990s has since abated due to a dramatic decrease in fighting among girls (and somewhat smaller one among boys).

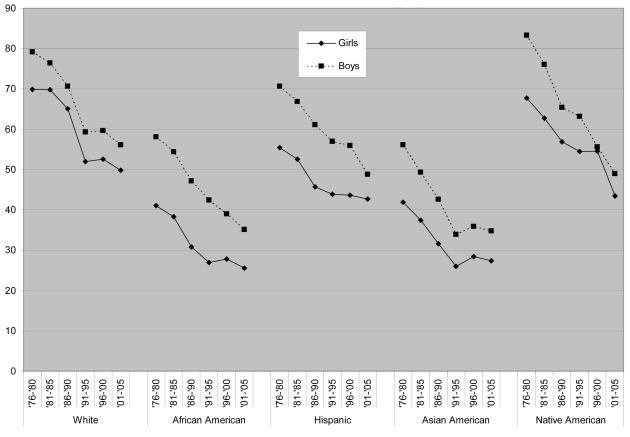

Turning to trends over time in reports of injuring someone (Figure 5), until the most recent time period there is little gender convergence among White youth, as both girls’ and boys’ rates were increasing gradually. However, recently there has been a slight gender convergence. This is due both to a steady increase in White girls’ rates of injuring someone and to a decrease in boys’ rates in the most recent time period. African American girls’ rates of injuring someone have also increased steadily over the past 30 years, while those of African American boys rose in the late 1980s and early 1990s but have since decreased somewhat. Overall, though, there is no gender convergence, as the increase in boys’ rates was so much larger than that of girls, leaving the current rates further apart now than they were in the late 1970s.

Figure 5.

Injuring someone badly, trends over time (1976–2005)

The results for Hispanic youth are similar, in that we see a relatively steady increase for girls’ rates of injuring someone over time, but no gender convergence because boys’ rates have generally been rising as well. Interestingly, Asian American girls’ rates of injuring someone have actually gone down over time, with boys’ rates remaining relatively stable (except for an anomalous drop in the early 1980s). Once again, there is no gender convergence. There is no gender convergence for Native American youth either, at least when you look at the most recent time period. Native American girls’ rates initially were going down, then increased in the 1990s (at which point there was some gender convergence), but have since dropped dramatically (demonstrating a gender divergence), while boys’ rates have remained relatively stable.

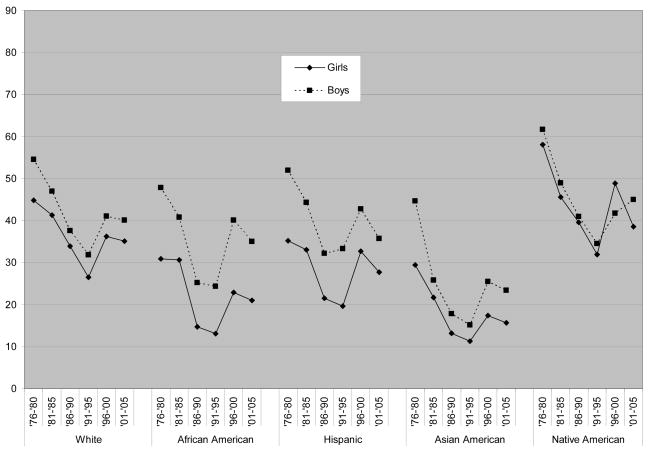

Substance use

As Figure 6 demonstrates, alcohol use has gone down for all groups of youth over the past 30 years. Most striking is the within racial/ethnic group gender similarity in patterns. There has been no gender convergence among White youth, but a slight gender convergence among African American youth due to the fact that African American boys’ rates have decreased more dramatically than those of girls. The story for Hispanic youth is similar, in that there is a recent gender convergence, but that it is due to a great decrease in boys’ alcohol use and not to any increase on the part of girls. Rates of alcohol use reached a low point for Asian American youth in the early 1990s, with little change thereafter. Again, the most interesting finding is the similarity between the patterns of girls and boys, with no real gender convergence. Native American youths’ rates of alcohol use do demonstrate some gender convergence, but, again, this is only because boys’ rates have gone down more quickly than those of girls.

Figure 6.

Alcohol use, trends over time (1976–2005)

Trends over time in marijuana use look a little different than those for alcohol use, as seen in Figure 7. In general, they reached a low point for all groups in the early 1990s, increased somewhat in the late 1990s (never returning to the high rates of the late 1970s), and decreased slightly in the most recent time period. Again, the most notable finding is the within racial/ethnic group gender similarity in patterns. There is no gender convergence for Whites or African Americans. There is, perhaps, a small gender convergence among Hispanic youth in the most recent time period, but this, again, is due to a greater decrease in boys’ rates of marijuana use. The story of Asian American youth is actually one of slight gender divergence in the past 10 years, mainly because boys’ rates increased more than those of girls in the late 1990s. Finally, Native American girls and boys demonstrate the most similarity in rates of marijuana use of any racial/ethnic group. Girls’ rates actually surpassed those of boys in the late 1990s, but, in the most recent time period, girls’ rates dropped while those of boys increased, demonstrating a slight gender divergence.

Figure 7.

Marijuana use, trends over time (1976–2005)

Discussion

The goal of this article was to assess whether self reports of violent behavior and substance abuse among American youth demonstrate gender convergence over time and to investigate variations in these patterns among girls and boys of different racial and ethnic groups. While limited with regard to the extent of questions on delinquency and the depth of understanding that these questions allow about why youth engage in these behaviors, the data used for these analyses have a number of important strengths. Because they are collected from large, nationally representative samples that measure youth behavior over a 30-year period, they allow us to examine variations in gender convergence in multiple racial/ethnic groups over an extensive time period, to develop a number of key conclusions regarding the extent to which the delinquent behavior of girls and boys has converged over time, and to identify several key questions that require additional exploration and inquiry.

Overall, our findings yield little support for the gender convergence hypothesis, because, with a few exceptions, the data do not show increases in girls’ violence or drug use. When there is gender convergence, it is almost always due to a decrease (or greater decrease) in boys’ violence or drug use, rather than to an increase in that of girls. There are two exceptions, however, where gender convergence might be due, at least in part, to an increase on the part of girls – fighting for African Americans and injuring someone for Whites. That self-reported rates of fighting have gone up for African American girls, and not for girls of any other racial/ethnic group, is a phenomenon in need of further exploration. Strikingly, it runs counter to the media depictions of girls’ supposed increase in violence, which frequently feature White girls. Why African American girls might be increasingly likely to be involved in fights is a question with many possible answers. The liberation theory, also referred to as the gender equality theory, does not seem to apply; it focuses more on White girls, because, as previously discussed, “doing masculinity” does not violate gendered expectations of African American girls. Instead, what some have termed the gender inequality theory of crime and delinquency may be instructive (Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996). The gender inequality theory is based on evidence that discrimination and poverty are associated with delinquency and crime in the general population, as well as on the fact that girls’ and women’s delinquency and crime are often responses to their economic marginality and victimization and a result of criminalization of their survival strategies (Chesney-Lind, 1989; Richie, 1995; Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996).

While most girls’ rates of fighting have not changed (with the exception of that of African Americans, previously discussed), rates of injuring someone for White, African American, and Hispanic girls have all gone up. Why is this so? It could be a reflection of an actual change in behavior, or it could be the result of increased willingness or even desire to make a claim about hurting someone badly – a much more subjective measure than that of engaging in a fight. It is here that the constructivist approach once again becomes relevant. Girls may actually be more likely to injure someone, but, especially given that only African American girls report being more likely to engage in fighting, it is plausible that girls are simply more likely to claim to have injured someone. This could be because in the past girls were unwilling to challenge internalized gender expectations by acknowledging having injured someone, or because it has become increasingly desirable to be able to make such a claim. The latter explanation is supported by glorified portrayals of girls and women in movies and on television as increasingly violent, but still sexy – e.g., Lara Croft tomb raider, Charlie’s Angels, etc. This unanswered question – as to whether the increase in girls’ self-reports of injuring someone reflects an actual increase in their violence or an increased willingness or desire to make such a claim – suggests that self-reports may not be perfect measures of young people’s behavior; it may be socially desirable to answer certain questions in specific ways – and that social desirability may look different at different times and in different contexts.

Nevertheless, we cannot dismiss the possibility that White, African American, and Hispanic girls have become more likely to injure someone. Why, though, the media focus on White girls if, according to self-reports, only African American girls’ rates of fighting have increased and reported rates of injuring someone have increased for White, African American, and Hispanic girls? Perhaps this is a reflection of White girls’ increased willingness to behave (or report behaving) in ways traditionally associated with girls of color (e.g., injuring someone). Thus, as Luke (2008) argues, anxiety over girls’ violence and delinquency “is not solely an anxiety about blurring and shifting gender norms. It is also an anxiety about blurring and shifting racial norms” (p. 45). Given these fears about blurring gender and racial norms, it makes sense that even slight growth in what has obviously become a very newsworthy event – serious violence committed by White girls – might prompt a disproportionate response. Qualitative research, including interviews and ethnographic studies of girls of varying racial/ethnic groups and social locations, is needed to begin to sort out these lingering questions.

In spite of its strengths, the analyses presented here have a number of limitations. Our use of data from high school seniors may underestimate the magnitude of violence and substance use among young people of this age, given that the most violence prone and heaviest substance users are likely to have dropped out of school by their senior year. Because of this possibility, we also examined the data collected from 8th and 10th graders. In general, the patterns and trends are similar to those reported here (although rates of violent behavior are generally higher and substance abuse lower among the 8th and 10th graders than among the 12th graders). Exceptions to these similar trends include the fact that self-reported fighting among 8th grade African American girls decreased in the most recent time period, as did injuring someone among 8th grade White and African American girls (although trends for 10th graders were similar to those of 12th graders). Nevertheless, our interest in the convergence hypothesis – a question that is explicitly about trends over time – necessitated that we use data from the group for whom we have the longest time period – high school seniors (as 8th and 10th graders were not interviewed until 1991).

These analyses were also restricted by the limited number of measures of violent behavior collected in the Monitoring the Future study. Given that girls’ violence is more likely to occur in private settings between girls and their relatives or romantic partners, and the evidence that the increase in girls’ arrests for assault is driven by arrests for domestic violence (Chesney-Lind, 2002; Steffensmeier et al., 2005), ideally we would have had a measure that asked specifically about such violence. Another limitation, as noted previously, is that the small sample of Native American youth included in the study necessitates that we interpret their results with caution. Finally, reliance on self-reports of delinquent behavior is also a limitation, the problems with which we have highlighted in our previous discussion. At the same time, the use of self-reports of behavior provides us with an important means with which to question the alarming increases in arrests of girls and boys in recent decades.

A comparison of trends in girls’ and boys’ arrest rates with those of their self-reports could lead one to conclude that girls have been underrepresented in the justice system and that justice is simply “catching up” with them. For example, in earlier years girls were approximately half as likely as boys to report fighting at school or work, whereas girls’ arrest rates in the 1980s were only one-third as high as boys’ rates. Similarly, a comparison of drug abuse arrest rates with rates of alcohol use or marijuana use could suggest that girls continue to be grossly underrepresented in arrests. However, when we consider the magnitude of the increases in arrests of both girls and boys alongside the relatively constant (or decreasing) self-reports of these behaviors, it is apparent that there is something more significant occurring.

Therefore, we note that even when girls’ violent behavior or drug use has increased, it has not increased nearly enough to account for the dramatic increases in girls’ arrests for violence and drug abuse violations. The data presented here indicate that alcohol and marijuana use in recent years are lower than they were 30 years ago. Given that the majority of girls do not enter the juvenile justice system for a violent offense and that there has been a 300% increase in the number of girls entering for drug offenses (OJJDP, 2007), our findings provide support for the work of Chesney-Lind and Paramore (2001), Steffensmeier and colleagues (2005), and others that has concluded that we must account for the increases in girls’ arrests by examining changing justice system policies and practices. Thus, additional research is needed to better understand how changing system policies and practices account for girls’ increased arrests and justice system involvement (e.g., “zero tolerance” and mandatory arrest policies, the war on drugs). Further, it must also seek to develop and evaluate alternatives to the justice system through the strengthening of community-based institutions and other approaches to youth development, as there is reason to question whether arresting young people, both girls and boys, and referring them to the juvenile court is an effective response to “delinquent” behaviors (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2008).

Future research must also attend to the increases in self reports of some violent behaviors among girls in specific racial and ethnic groups. While it is clear that girls continue to report engaging in violence at very low rates, increases in reports of violent behavior (whether they reflect actual changes in behavior or just of reporting of it) are troubling and suggest the need for attention. Consequently, additional research is necessary to better understand the increase in African American girls’ reports of fighting and of White, African American, and Hispanic girls’ reports of injuring someone and to further explicate how the structural conditions in which girls live shape the ways that they navigate, negotiate, and report violence in their lives.

Finally, future research should address how the lives of these girls and societal responses to their behavior have been shaped by neo-liberal policies that have led to a dismantling of the welfare state and substantial growth in the justice systems. These issues are of particular importance to social workers and social service providers charged with developing and implementing interventions for girls, as we seek to contextualize our understandings of girls’ needs in the current climate of unprecedented incarceration rates for people of both genders in the U.S., where we now have the highest rates of incarceration in the world (Pew Center on the States, 2008). The importance of locating these questions within the broader social context is evidenced by the fact that our work, in conjunction with other studies, suggests that the increasing arrest and adjudication of girls is not a result of their changing behavior, but, instead, of changing policies and practices within our justice and social service systems.

Footnotes

The violent crime index includes murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.

Many scholars (e.g., Chesney-Lind & Pasko, 2004) note that use of percentage increases exaggerates the change in girls’ arrests because the numbers are so much smaller for girls in the first place. Thus, the changes of the 1990s evident in Figure 1 can be stated in two different ways. We can say that girls’ arrests for violent crime increased between 1980 and their peak in 1995 by 124%, while boys increased only 46% during this period, making it seem that the increase for girls was much more dramatic. Alternatively, we can say that girls’ rates increased by 87 per 100,000, while boys’ increased by 269 per 100,000 – a representation which emphasizes the fact that in absolute numbers, boys’ increase was much larger (over 3 times larger in fact) than that of girls.

Nevertheless, punishment and incarceration have greatly increased during this period (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2008).

Findings for 8th and 10th graders are generally consistent with those for 12th graders and are available from the authors.

Respondents who chose multiple races/ethnicities or other categories are omitted.

We recognize that each of these racial and ethnic groups is diverse and treating them as homogenous may mask important within- and between-group differences. Ideally, more refined racial and ethnic subgroup measures would be used; unfortunately, these measures are not available in the dataset.

Because Monitoring the Future was not designed specifically to assess violent behavior, there are a very limited number of measures available for assessing it.

We calculated 95% confidence intervals for all of the observed estimates reported in Table 2 (available from the authors). Unless otherwise noted, differences discussed in the text are statistically significant. For every racial/ethnic subgroup on all measures included here, boys’ rates were significantly higher than those of girls, with the exception of alcohol and marijuana use among Native American youth, for which the 95% confidence intervals overlapped.

Although, for each of these groups of boys, the 95% confidence intervals for the two measures overlap somewhat.

Given the small sample size of Native American youth, however, these differences are not statistically significant.

Although for girls, the confidence intervals of Native Americans overlap with those of Whites and Hispanics.

We do not present the trends over time for the entire sample, as these are largely similar to those of White youth because White youth make up the overwhelming majority of the sample.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sara Goodkind, University of Pittsburgh, School of Social Work and Center on Race and Social Problems

John M. Wallace, Jr., University of Pittsburgh, School of Social Work and Center on Race and Social Problems

Jeffrey J. Shook, University of Pittsburgh, School of Social Work and Center on Race and Social Problems

Jerald Bachman, University of Michigan

Patrick O’Malley, University of Michigan

References

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. A Roadmap for Juvenile Justice Reform. Baltimore, MD: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. The Monitoring the Future project after thirty-two years: Design and procedures (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 64) Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Corrections Statistics. Washington, DC: Author; 2008. [Accessed on March 9, 2008]. http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/glance/incrt.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington K. Does feminism spoil girls? Explanations for official rises in female delinquency. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2006;39(1):34–53. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano SM. Criminal victimization, 2005. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M. Girls’ crime and woman’s place: Toward a feminist model of female delinquency. Crime & Delinquency. 1989;35(1):5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M. Criminalizing victimization: the unintended consequences of pro-arrest policies for girls and women. Criminology and Public Policy. 2002;2:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M, Paramore VV. Are girls getting more violent? Exploring juvenile robbery trends. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2001;17(2):142–166. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M, Pasko L. The female offender: Girls, women, and crime. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Fighting words: Black women and the search for justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. See Jane hit: Why girls are growing more violent and what can be done about it. New York: Penguin Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hsia HM, Bridges GS, McHale R. Disproportionate minority confinement 2002 update. Washington, DC: OJJDP; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2005 (NIH Publication No. 06-5882) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Luke KP. Are girls really becoming more violent? A critical analysis. Affilia. 2008;23(1):38–50. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Juvenile Justice. [Accessed on July 15, 2008];Juvenile Arrest Rates by Offense, Sex, and Race. 2007 http://ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/crime/excel/JAR_2006.xls.

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985–2004. Washington, DC: Author; 2007. [Accessed on March 9, 2008]. http://ojjdp.ncjrs.gov/ojstatbb/ezajcs/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Center on the States. One in 100: Behind bars in America 2008. Washington, DC: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prothrow-Stith D, Spivak HR. Sugar and spice and no longer nice: how we can stop girls’ violence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rand MR, Lynch JP, Cantor D. Criminal victimization, 1973–95. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Richie BE. Compelled to crime: The gendered entrapment of battered black women. London: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Scelfo J. Bad girls go wild. [Accessed online March 10, 2008];Newsweek. 2005 June 13; http://www.newsweek.com/id/50082.

- Smart C. Women, crime and criminology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN, Sigmund M. Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 National report. Washington DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H. Juvenile Arrests. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2006. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl AL, Puzzanchera C, Livsey S, Sladky A, Finnegan TA, Tierney N, Snyder HN. Juvenile court statistics 2003–2004. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier D, Allan E. Gender and crime: Toward a gendered theory of female offending. Annual Review of Sociology. 1996;22:459–488. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier D, Schwartz J, Zhong H, Ackerman J. An assessment of recent trends in girls’ violence using diverse longitudinal sources: Is the gender gap closing? Criminology. 2005;43:355–405. [Google Scholar]