Abstract

Virtually all migration research examines international migration or urbanization. Yet understudied rural migrants are of critical concern for environmental conservation and rural sustainable development. Despite the fact that a relatively small number of all migrants settle remote rural frontiers, these are the agents responsible for perhaps most of the tropical deforestation on the planet. Further, rural migrants are among the most destitute people worldwide in terms of economic and human development. While a host of research has investigated deforestation resulting from frontier migration, and a modest literature has emerged on frontier development, this article explores the necessary antecedent to tropical deforestation and poverty along agricultural frontiers: out-migration from origin areas. The data come from a 2000 survey with community leaders and key informants in 16 municipios of migrant origin to the Maya Biosphere Reserve (MBR), Petén, Guatemala. A common denominator among communities of migration origin to the Petén frontier was unequal resource access, usually land. Nevertheless, the factors driving resource scarcity were widely variable. Land degradation, land consolidation, and population growth prevailed in some communities but not in others. Despite similar exposure to community and regional level push factors, most people in the sampled communities did not out-migrate, suggesting that any one or combination of factors is not necessarily sufficient for out-migration.

Keywords: rural-rural migration, Guatemala, Latin America, population, environment

I. Introduction

The most conspicuous shortcoming of current research on deforestation is the failure to explicitly examine the antecedents to deforestation on the agricultural frontier. Given the dominant roles of migrant colonists in land clearing, this means understanding the decisions of farm families to leave origin areas to migrate to the frontier. Yet of the work on internal migration in developing countries, almost all is on rural-urban migration, most based upon survey data obtained only in destination areas (SEGEPLAN 1987). In effect, rural-rural migrants have been largely ignored in the migration and development literatures, even though they are the key migrants in studies of population-environment relationships (Bilsborrow and Geores, 1992; Bilsborrow, 2001).i Thus, two critical questions remain unanswered: 1), who migrates from rural areas of origin; and 2), among these, who chooses the agricultural frontier as their destination?

Regarding factors leading to out-migration from rural communities in general, Wood, (1982), Bilsborrow (1987), Massey (1990), Findley and Li (1999), and others argue for a broad, structural approach that both takes into account a range of economic and non-economic factors embodied in perceived “place utility,” (Wolpert 1965; Wolpert 1966; Bible and Brown 1981) and also incorporates structural or community-level factors that measure the context within which migration decisions are made. Empirical studies have implemented these approaches effectively (Lee 1985; Bilsborrow et al. 1987; Brown and Sierra 1994; Findley 1994; Laurian et al. 1998).

Migration to agricultural frontiers has been researched in the Ecuadorian Amazon (Pichón 1996), Honduras (Stonich 1993), Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula (Haenn 1999), and Guatemala’s Petén (Schwartz 1995). A variety of hypotheses have been posited in the land use and political ecology literatures focusing on macro-level economic and political factors, with little in the way of analyses at community and household level, where decision-makers actually operate (Stonich 1989; Southgate 1990; Barbier 2000). While skewed land distribution in origin areas is frequently a migration push, access to free land is a common migration pull (Rudel 1995; Clark 2000). Environmental factors affecting internal migration include timing of rainfall (Henry and Schoumaker 2004) and drought (Ezra and Kiros 2001), and a host of other factors relating to environmental change (Pebley 1998; Bates 2002). Socio-economic factors found associated with agricultural internal migration include land ownership (VanWey 2003), and relative deprivation – which is often linked to land ownership in rural settings. The effects of migration networks are also increasingly emerging in the literature as key determinants of timing and location of migration, as illustrated, for example, in recent studies from Mexico (Verduzco 1995; Davis et al. 2002; Curran and Rivero-Fuentes 2003).

Despite some agreements on common trends in the emerging literature, explanations of migration have often failed to recognize that the conditions sufficient for out-migration do not necessarily lead to migration, much less to the frontier. Indeed, the vast majority of people in (rural) places do not move, and of those who do, most do not choose the frontier as their destination. Therefore, examining the modest population that out-migrates, and why they choose to migrate to the frontier, is essential to understand colonist deforestation, and has significant implications for identifying policies to address its root cause—geographies of spatial inequalities.

Background

Guatemala highly unequal resource distribution—resulting in a lack of technological access and knowledge, land and alternative employment opportunities for small farm families—is a common denominator of areas of high out-migration. Cultivable land per capita in the country fell from 1.7 to 0.8 hectares between 1950 and 1979 (the date of the last agricultural census). During this time over 150,000 new sub-subsistence farms were created under 1.5 acres (SEGEPLAN 1987). Compounding problems of skewed land distribution, in many areas—most notably the highlands and Verapaces—political violence displaced hundreds of thousands of peasants during the 1980s (Aguayo et al. 1987; Morrison and May 1989). Further, the extreme concentration of landholdings and underemployment, combined with the highest rural fertility rate in Central America,ii led to fragmentation of farm plots and rural poverty, stimulating out-migration (Bilsborrow and Stupp 1997). Despite these processes, most rural Guatemalans have remained in their origin areas, while most of those who migrate go to the U.S. or to Guatemala City rather than to the frontier. Little is known about this minority that has migrated to the frontier, let alone why they chose such a destination. This article investigates this phenomenon through data collected in both migrant origin and destination areas.

Approximately half of all men and women out-migrated temporarily from origin communities at some time during the 1990s (Table 1; Carr 2000). Most traveled to Guatemala City and to local towns and plantations with a minority choosing the US as a destination. Seasonal out-migrants tended to work in southern Petén and Alta Verapaz, rather than the northern Petén where day labor is less lucrative (Carr 2000). Approximately 10% of origin area adults permanently out-migrated during the 1990s. The peak of out-migration coincided with the period of greatest in-migration to the SLNP: the height of the civil war in the 1980s and 1990s. Despite representing the areas of highest out-migration to the SLNP, an equal number migrated to Guatemala City as to Petén. Two out three out-migrants chose one of these two destinations, (Carr 2000). Factory and service employment was a migration pull to Guatemala City while land availability emerged as the main pull to Petén (Carr 2000).

Table 1.

Migration Pushes and Pulls (1989–1999)

| Percent of adult seasonal migrants | Approximate Mean | |

| 50% | ||

| Percent of adults permanently out-migrating | Approximate Mean | |

| Men | 10% | |

| Push factor | Pull factor | Principal Destinations |

| Lack of jobs | Wage labor | Guatemala City, US |

| Poor access to education | Educational opportunities | Guatemala City |

| Lack of land | Land availability | Petén |

| Natural disasters | Decreased vulnerability | Petén |

| Environmental degradation | Better quality land | Petén |

II. Methods

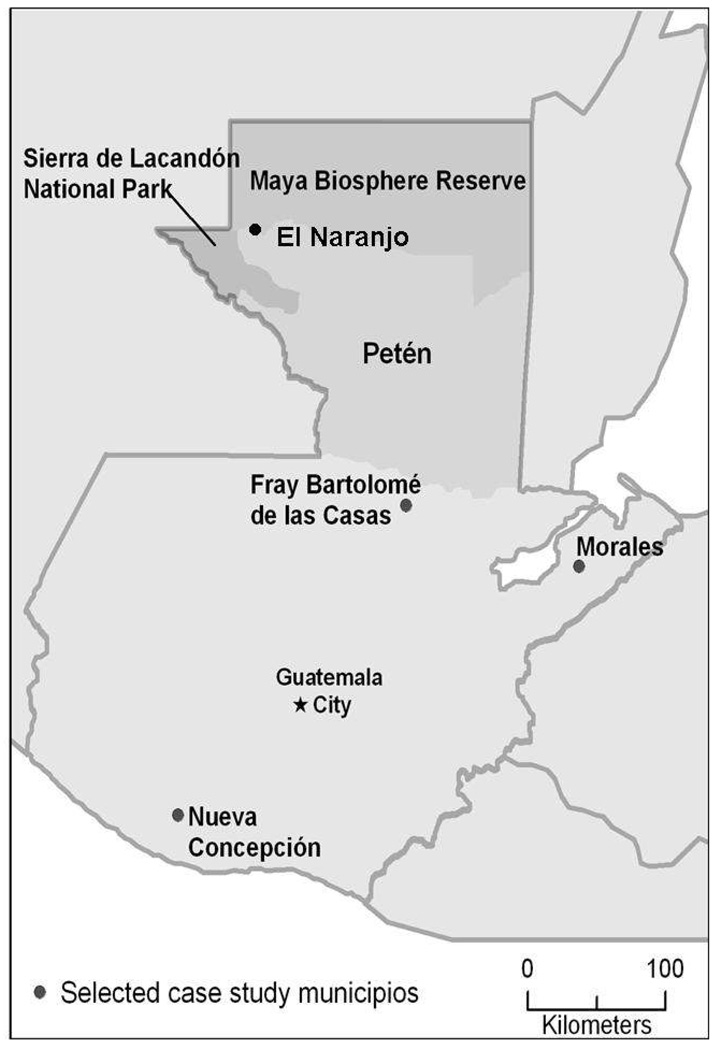

In 1999 and 2000 I carried out a survey in areas of migrant origin to the Maya Biosphere Reserve (MBR), employing municipio (similar to a U.S. county) and community-level questionnaires, to gain insights into the factors underlying migration to a core conservation zone of the MBR, and a site of rapid colonization during the 1990s, the Sierra de Lacandón National Park (SLNP).iii I interviewed community and municipal leaders and other informants (the latter randomly selected) in Spanish and Q’eqchi Maya in 28 communities in 16 municipios of highest out-migration to the SLNP (Map 1). Municipios were selected from 1993 Guatemala census data and were corroborated as key regions of out-migration to the SLNP by my 1998 household and community surveys in the SLNP (Carr, 2003, 2005). Data were collected on topics similar to those undertaken previously in destination communities in the SLNP, but included additional questions on in- and out-migration, perceived reasons for people leaving and main destinations. Five to ten informants were interviewed in each of the 28 communities. Two to three days were spent in each community and interviews were conducted individually for approximately 1–2 hours each. Independent measures were used to assess the accuracy (validity) and reliability of informant statements including asking the informant similar questions repeatedly, and corroborating data with other informants.

Map 1.

Guatemala and Origin Communities to the Petén Frontier

Common to all source regions for frontier migration was insufficient access to resources, especially with regards to land but also including other forms of capital, due to unequal land concentration, population growth, and land degradation (Carr, 2000). Nevertheless, while the factors examined are the same, the values or magnitude emerged differently in each place. This spatial heterogeneity is crucial to understanding household responses in terms of land use or migration, and when, where, and how these responses take place. This paper describes examples from three municipios of migration origin to illustrate why simplified narratives explaining frontier migration such as land degradation, population growth, or poverty in origin areas insufficiently describe the real causes of frontier out-migration and why, ultimately, place matters. Case studies are presented from three municipios of high out-migration to the SLNP: Morales, Izabal in the Southeast; Nueva Concepción, Escuintla in the Pacific Littoral; and Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, Alta Verapaz, in the Verapaces. These municipios serve as three examples of how distinct, local processes in diverse geographical locations ultimately fostered out-migration to the frontier and elsewhere as well as other, alternative responses.

III. Out-migration from Three Municipios: Why Place Matters

1. Southeast: Land Consolidation, Violence and Hurricane Havoc in Morales, Izabal

When the banana company leaves, I don’t know what we’re going to do.

-Informant from Morales

Out-migration from the municipio of Morales (Figure 1) can largely be traced to processes of land consolidation by large plantation owners as an underlying factor and environmental change as a precipitating direct cause. Plantations offer wage labor for some, but little land is available for small farmers. Like other banana-producing regions in the departamento of Izabal, Morales’s population and export-producing economy grew during the middle decades of the 20th century. Initially a magnet for rural laborers, plantation expansion increasingly pushed colonist small farmers out of the land market, leaving plantation work one of the few viable options for wage income. Though population growth has been a factor in the subsequent fragmentation of farm plots, plantation expansion has left virtually no productive lands for small farm families. This process of land consolidation set the conditions for massive out-migration of peasant families from the municipio in recent decades. However, these conditions were necessary but insufficient for many migrants and migration for many was ultimately triggered by a series of devastating floods.

Figure 1.

Community characteristics

A member of the town council, a health promoter, and several other residents of La Democracia and the mayor’s family in La Colina spoke about their respective communities in Morales. Both places exemplify notable economic and demographic processes unleashed by intense land concentration. In both communities, land consolidation has left families dependent on renting small plots and working as day laborers on the local banana plantation. The plantation is part of a complex owned today by a large international fruit export company and previously owned by the United Fruit Company from 1890 to 1960. Household economies in both communities are almost entirely dependent on the local banana plantation. La Democracia, a community of approximately 3,000 people, exists primarily as a source of labor for the plantation. Conversely, the village of La Colina (approximately 1,500 people) is located several kilometers to the south of the plantation, in the foothills near the Honduran border. Land here is too hilly to have been coveted by the banana plantation and has largely been consolidated in the hands of cattle ranchers. Still virtually all of the households in both communities have a member who is working or has worked in the local banana plantation. As one man commented “when the banana company leaves, I don’t know what we’re going to do.” Indeed, few other options are available. The non-agricultural sector provides jobs for fewer than 10% of the residents.

Residents of both communities are predominantly Ladinos from the nearby departamentos bordering Honduras to the south (see Map 1.). The mayor’s wife in La Colina explained that young families used to come to find plots from Jutiapa (a departamento located to the west of Morales). “But now” she laments, “most of the land in the surrounding area is in banana plantations and cattle ranches.” As a result, farmed land must be rented from these largeholders. Approximately half of the households in each community rent land from the banana plantation or from large landholders in surrounding communities. Most sow maize and other subsistence crops on one or two hectare plots. Only a handful enjoy as many as three hectares. Further pressuring poor households, a one manzana parcel (0.7 hectares) costs between Q10,000 and 20,000, in the range of $1,500 to $3,000 dollars, pricing land ownership of even the most modest farm out of reach of the majority. Renting is a more viable option, though its cost, at Q300 (approximately $40 USD) per manzana per harvest, represents a substantial portion of yearly revenues.

Migration patterns

Approximately a third of the men migrated to the US during the ten years prior to interviews and approximately 10% of the women migrated to Guatemala City during the same period. In the first case men usually work for two or three years and return. In the second case, women labor for several months to a year, often as domestics workers. A small fraction of men also travel to Guatemala City for several months at a time to work in construction.

Permanent out-migration flows are much smaller. Fewer than 10% of the households in the two communities out-migrated permanently during the 1990s. The US represented the main destination for permanent migrants. A small group of migrants also remains in Guatemala City, especially if they have family and friends already permanently established there. The third most common permanent destination is the Petén.

Since the majority do not out-migrate, an important question is “Who does migrate?” One informant summed up migration this way: “Risk-takers migrate, and they go where they will be paid.” Another man summed up migration from La Colina by saying: “People leave to improve their economic situation, the lack of land, or work since the banana plantation pays so poorly.”

Why people left

Informants from both communities cited land consolidation, scant employment opportunities, and low wages as the primary structural, or underlying, factors for out-migration. But the primary direct cause more recently has been the devastation left by flooding. Indeed, erosion and soil deposition from flooding are cited as the principal motives for out-migration from both communities. Flooding has eroded topsoil on some farms and buried crops beneath a thick layer of recently deposited muck on others.

Some of the comments relating to environmental reasons for migrating included the following: “Because of the natural disasters, there’s no more good land and land has to be sought elsewhere…natural disasters have placed the community in crisis.” “There is no land and no money…the land has been degraded from the disasters.” “Poverty has increased here because of Hurricane Mitch in 1997 and many went to the US as a result.” Similarly, La Colina, located on the Moyuta River, which drains the Verapaz mountains, was severely flooded following the downpours of Hurricane Mitch and many people have yet to recover from the economic losses. Locals lamented that their crops were destroyed and that erosion had necessitated the heavy use of fertilizers and herbicides. Even perennials such as mangoes were ripped from the topsoil by the hurricane-force winds and gushing water.

Ironically, when floods are uncommonly severe, out-migration is reduced. For example, immediately following Hurricane Mitch out-migration was suddenly stemmed. Locals explained that there was “plenty of work in plantations repairing buildings, fences, and drainage pipes and people had little money to migrate to the US.” Further, as crops were severely damaged or destroyed, and news reached the US of the disaster, family members in the US increased remittance payments. Now, several years after Mitch has passed through the area, reparation work has dried up and some farms remain severely damaged. Thus, in recent years, migration has picked up once again. Initially a reason for staying, the aftermath of Mitch has reminded people of the fragility of their environment and has encouraged families from La Democracia to migrate to the US and to Guatemala City, far from the reach of the Montagua River’s crest. Lastly, in addition to floods, political violence was a precipitating factor for out-migration among some households during the 1980s. Since these migration flows were concentrated to the Petén, I will discuss this phenomenon in the following section.

Where people went

There are three types of migrants according to a senior resident of La Democracia: Migrants to the capital are wage earners, US migrants are wage earners and agricultural workers, and migrants to Belize and Petén are “only agricultural laborers.” Other informants agreed with this assessment. Another man, for example, related that “people that go to the Petén are farmers, they are not professional workers.” A third mentioned, “in the city there is no work if you are not a professional (unskilled – without a trade).” Conversely, “In Petén they are people that like to work the land and that don’t want to work in towns.” However, some of the informants mentioned that now the majority who go to Petén do not settle there permanently since the land is already occupied. Rather they go “near the Belize border, only in summer…to clear land for maize and frijol because it rains too much here. Many people now go there from October to January. They have friends there now and they rent land for a third maize harvest from cattle ranchers.” Most agree that those who go to Petén are often landless, which suggests another characteristic of out-migrants to the Petén.

The United States has been the primary destination of migrants from both communities. Community leaders estimate that approximately one-third of the families from each community left for the United States during the 1990s alone. It is typical for people to remain in the US for up to three years. This northward migration flow has been a boon to household economies. According to one informant “The economy is better off because you can feel the effect of the remittances, the dollars that come from there.” The destination of US-bound migrants from La Democracia has been primarily Los Angeles while La Colina’s migrants have settled in Washington, DC, New York City, and Los Angeles.

Many of the families that left owned small farms and sold them to the plantation owners or to successful small farmers, catalyzing the land consolidation process. Locals explained that sometimes support from family and friends is insufficient for successful migration to the US and money is loaned from a professional lender and repaid later through monthly remittances. Informants in both communities agreed that those who go to the United States have money to pay for the trip as well as family who help them undertake the risky voyage and find work once there. As one plantation hand concluded “Those who go to the US have money and make much more money once they are there. It is much better there. The agriculture is more ‘grown-up’ in the US.”

La Democracia and La Colina differed from other communities in the study in that few households have migrated to Guatemala City. A mere 5% have migrated to the national capital—usually for a few months or up to a year. Men work mainly in construction while women work domestic jobs. Informants lamented that “In Guatemala City it is difficult to find work.” Another informant mentioned that some go to Guatemala City, but added there is “lots of vice.”

The civil war emerged as a push for some migrants to the Petén during the 1980s. During these years, some men were identified—usually falsely according to the informants—as rebel insurgents. In the late 1980s, fifteen families from La Colina and four from La Democracia migrated to the Naranjo road because of violence. According to community members, almost all of the migrants who left because of violence went to the SLNP frontier. An attractive pull factor to the frontier would appear to be its remote location, far from trouble. Yet migration to the frontier was not without its war-time risks. The Lacandón forest was the site of intense skirmishes between guerrillas and government forces. Therefore, it is possible that migration to the SLNP for some was for the purpose of joining forces with other rebel groups or with others who had been identified (falsely or not) as rebel insurgents. The Comunidades Populares en Resistencia (CPR), a major resistance movement against the war-time government, formed several small communities controlling vast areas of the northern SLNP. It is unclear which of these two factors, violence or land, was the primary motivation for migration to the Petén among those identified as insurgents.

It appears that acquiring land was the main motive for some, since informants agreed that an important pull factor to northern Petén was the vast land suddenly made available by the newly-opened Naranjo road in the mid 1980s. A town official from La Colina noted that until four or five years ago some families migrated to the Petén frontier area of the SLNP. But this migration stream ceased, according to the official, because “there is no more land in the Naranjo area. “We know this,” he contended, “because people leave to investigate and return.” Another assented, adding that “few go to the Naranjo area now because a few years ago some families went there and returned informing us that there was no more land there…people no longer go there because it is becoming as bad there as it is here…with the construction of the roads, the land prices have gone up.”

Out-migration from the municipio of Morales can largely be traced to processes of land consolidation by large plantation owners as an underlying factor and ecological change as a precipitating direct cause. Violence also was a direct factor for a small number of families to move to the SLNP frontier in the 1980s. Informants in both communities anticipate that these trends will continue, meaning that both land and work will be scarce for their children. As one man said, “Today, if there were no plantation here, people would have no place to turn for work…people have left because they have nothing.” Another noted that their children will have to depend on a good health center with family planning if there is to be enough work for everyone in town. This man is cautiously optimistic that there could be sufficient work for today’s children when they are adults since “unlike before when young women would start having children at fourteen, now couples plan before having so many children.” If that is so, he believes, there will be enough work on the banana plantations for the next generation. On the other hand, he considered, “they will be better off if they can get non-agricultural jobs.” He may have a point. Steadily declining fertility may help keep the supply/demand ratio for labor from bloating in favor of employers in small communities in Morales such as has occurred in La Democracia and La Colina. Nevertheless, dwindling opportunities for the small farm household from past, and possibly future, land consolidation in Morales, may make curbing population pressures moot.

2. Pacific Littoral: Population Growth, Land Fragmentation, and Environmental Degradation in Nueva Concepción, Escuintla

The kids grow like weeds and then there is no land.

-informant from Nueva Concepción

In stark contrast to Morales—and an anomalous case for rural Latin America—land consolidation has been virtually absent in Nueva Concepción (Figure 2.). In 1954, this municipio realized Socialist President Jacobo Arbenz’ dream of land redistribution following his alleged US-backed assassination (Premo 1981). Large plantations were splintered and doled out in 28-hectare parcels to colonist families. Agricultural colonists flooded the municipio, many coming from eastern regions (e.g., Izabal, Zacapa, Jalapa) where farmland had become scarce in a region dominated by the United Fruit Company. Since this rare land redistribution event took place, large land owners have not consolidated holdings in this municipio, glorified in its early years as the “breadbasket of Central America (SEGEPLAN 1987).” Small farms have yet to be gobbled up by large plantations. What has changed the size and distribution of landholdings in Nueva Concepción instead is subdivision through two generations of large families. Today the average farm size reported in three communities and by municipio officials is between two and five hectares. This dramatic plot fragmentation has spurred—and has continued in spite of—mass migration to the US and to the frontier.

Figure 2.

Community characteristics

Community leaders and key informants in three communities sampled in Nueva Concepción municipio provided information for this case study. Santa María and El Paraíso are larger communities with populations hovering between 2,000 and 3,000, depending on seasonal migration. Las Brechas IV is much smaller with approximately 350 people. All three communities are approximately half Catholic and half Evangelical and are largely comprised of Ladinos, descendants of the first colonists from the southeastern departments (e.g., Jalapa, Jutiapa, Izabal) who came to the municipio in the-mid 1950s during the period of land reform. In Santa María and Las Brechas, 90% of the community owns no land of their own and nearly three-quarters work in non-agricultural jobs or on sugar cane plantations. Informants note the marked difference in the landless rate today compared to 0% in 1955 and 40% as little as twenty years ago.

Virtually everyone works in agriculture in the three communities and average farm size for those who have access to land (nearly half the households) ranges from 5.0 manzanas in the more remote Las Brechas to 0.5 hectares in Santa María and El Paraíso. Most rent land on large sugar cane plantations, typically growing one manzana of maize for subsistence to complement sporadic labor in local plantations or seasonal migration. One source of employment and land for rent is a sugar plantation outside the community that encompasses seventy caballerias (over 3,000 hectares).

Land prices reflect the high population density, good volcanic soils, and well-connected transportation routes of the region. In the larger and more connected villages of Santa María and El Paraíso, one manzana of land can fetch in the range of 30,000 Quetzales, while in the more remote Las Brechas, the price is still a hefty Q15,000. In other words, what was free in 1954 is today valued at $60,000 to $120,000 USD for a 28 manzana (20 hectares) farm, far too much for an average household to afford.

Migration patterns

Facilitated by proximity to the Pan-American highway and Guatemala City, most of the men and a minority of the women have out-migrated temporarily from the three communities. The principal destinations of the temporary migrants in the three communities are Guatemala City and the US. A third temporary migration option is work in the nearby city of Tiquisate.

Permanent migration was less common but substantial nonetheless. In Las Brechas and El Paraíso permanent out-migration was higher than in Santa María. Approximately one quarter of households migrated permanently to the US, Guatemala City or Petén during the 1990s in the first two communities, compared to only ten percent in Santa María.

As in Morales, out-migration peaked from the municipio during the 1980s. In Las Brechas, for example, locals claimed that it is possible that most of the permanent out-migration from the village since the 1950s occurred during the 1980s alone. Still, locals estimated that approximately 10% of the entire village migrated (some permanently others temporarily), specifically to Los Angeles and Miami during the 1990s.

Why people left

Informants in the three communities concurred that a crucial out-migration push in recent decades has been the population growth. Community leaders estimated that women have five to seven children or more on average. As one small farmer exclaimed, with twelve or fourteen children there is not enough land for everyone. “It is hard to support so many,” echoed one young woman, waiting for a bus in the town center of El Paraíso. Yet this sentiment is not shared by all. One older woman piped in with pride “I was yearly with my births, each year I was raising a new [child].”

But Alejandro, a local banana farmer, feels his brother’s experience was fairly typical. Alejandro’s brother was lured from his native department of Jalapa by the offer of free land in the 1950s. Alejandro’s brother obtained a title in 1954. But, he explains, “there wasn’t enough land for so many children.” Thus, his brother was compelled to move the family to Petén in the mid-1980s.

As in Morales, a second reason cited for out-migration was flooding, most recently and severely from Hurricane Mitch. Yet informants complained that despite public works funded by the government, the local river floods not only following major hurricanes but also with each rainy season. Similarly, in El Paraíso, residents cite heavy rains and erosion as the primary reason for out-migration. As a result of erosion from floods and nutrient degradation from many years of intensive cropping, locals in the three communities reported the necessity of adding fertilizer to maize crops. Doing so helps increase production from thirty to forty quintales per manzana to sixty quintales per manzana—roughly the average yield of SLNP farmers without fertilizer. Lastly, some note that violence, during the period of greatest out-migration in the late 1980s and early 1990s, was also a factor in several households leaving communities in each of the three municipios.

Where people went

As mentioned above, most permanent migrants have gone to the US, but the Petén is a close second. Unlike most communities surveyed, many of the migrants to the US from the three communities in Nueva Concepción have remained for several years and apparently have no intention of returning home. Perhaps the fact that young adults in these communities come from migrant families who settled the region only recently diminishes their attachment to Nueva Concepción as their home. Nonetheless, they seem to be faring well and are considered heroes for succeeding in the US, as evidenced by the trucks and other expensive items purchased from remittances sent home. As one man crowed, “Look at this truck, look at those new additions on the houses. All this money comes from friends and relatives living in the US! We have nothing here. We could not afford this.”

Locals claimed that people used to send children to Guatemala City for school while others went to Petén to acquire land. Migration to Guatemala City is usually temporary, informants explained, though it can become permanent when children go to school there and remain because they have found work or have married a capitalino/a. As one informant noted “there is no fun or good education in Petén…which is [another reason] why people go to the capital.” Another man echoed this response. He acquired almost 100 hectares in Petén as a rubber tapper in the late 1950s but returned after a few years because “the conditions were very rough there.” But, he insists, “Petén is vast and remains a font of open land. If I were young I would go again.” In Petén, he continued, “there are offices that grant land and people have lots of family and friends.” Informants in the three communities related that young adults with a recently formed household are more likely to go to Petén than are young single men and women. Migrants to the US or Guatemala City almost always have friends or relatives in the destination area, whereas for migrants to Petén this is not always the case. Because of the absence of social networks, some opine that migration to the Petén is as risky as to the US, just for different reasons.

Of the migrants to Petén, many settled in La Libertad, the municipio where the SLNP is located, during the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. These were years of intense political violence but, perhaps of more significance, these years also coincided with the coming of age of the second generation of landholders following the municipio’s 1954 land redistribution. Indeed, respondents claimed that the 1980s and 1990s were times of high out-migration to Petén because “people left for lack of land.” Nevertheless, one man claimed, “It is more difficult in Petén…because the conditions are unfavorable and uncomfortable.” He continues that “in El Paraíso there is a tractor, in Petén they ploughed by beast, but it is more ample for cattle to roam…and for the children. There is life in Petén.” He continued “Petén is better for those who have nothing here. If you have a farm here, you live ok. It is difficult for those without land because they have to rent. It is better to go to Petén than to rent because there is lots of idle land but it lacks access.”

In sum, informants concurred that, unlike the dominant narrative describing the situation in Morales and pervasively throughout Latin America, land consolidation by large land owners was a non-factor in out-migration from La Nueva Concepción. Sporadic employment, land degradation, flooding, and violence were all important push factors. But many pointed to the rapid coming of age of children and the challenge to find land for them as a major reason for out-migration from the region. As one man stated, “The kids grow like weeds and then there is no land.” He continued, “For young people, it is better for them to go to Petén.” In Nueva Concepción it appears that many children “growing like weeds”, not land consolidation, was largely responsible for out-migration.

3. The Verapaces: A “Gold” Rush of Maize, Violence, and Out-migration in Fray Bartolomé de las Casas

Some had one caballeria of land, others had half of a caballeria. People fled troops from both sides.

-Informant from Fray Bartolomé de las Casas

In Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, relieving pressures through frontier colonization was not a sustainable solution (Figure 3). Population growth and land consolidation transformed this region from a colonization frontier to a region of net out-migration within two decades. Fray was part of a planned colonization scheme sponsored by the government in the 1960s to encourage settlement of the Franja Transversal del Norte Region of northern Quiche and Alta Verapaz (Milián et al 2002; Katz 2000; Beavers 1995; Jones, 1990). In a maize gold rush, Q’eqchí, from municipios to the east, along with a small number of Pocomchi' and Ladinos from Baja Verapaz and the South, settled this portion of eastern Alta Verapaz starting in the 1950s, but mainly in the 1960s and 1970s. With the intervention of INTA (The National Institute for Agrarian Reform) a portion of several contiguous municipios (San Luís, Petén, Cahabón Alta Verapaz and Chisec, Alta Verapaz was cleaved to form Fray. INTA granted 32 manzana (approximately 20 hectares) farms to early settlers. But by the late 1970s unsettled land was scarce and land consolidation by cattle ranchers was well under way. These processes set the conditions for out-migration that was ultimately precipitated in some communities by violence.

Figure 3.

Community characteristics

Community leaders in three communities in Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, El Limonero, Fuerte Campesino, and San Juan el Mirador, participated in interviews. Informants in all three agreed that population pressure on the land has increased in recent years and land consolidation by cattle ranches and coffee and cardomom plantations is acute. Only a small fraction of farmers have title to their land in the three communities. Though land titling has intensified in recent years, most farmers remain squatters. For those who are landless, renting costs from 1,000/1,500 Quetzales per manzana, more than double the price in the early 1990s, and much more expensive than in the SLNP (yet still less than in other, longer-settled areas). Households farm maize and frijol for subsistence and some rice is grown in a few lowland areas.

Migration patterns

Similarly to Morales, landlessness due to land consolidation contributed to out-migration starting in the 1980s and continuing to this day. But the war was directly responsible for the timing of the most dramatic out-migration flows from many parts of the municipio. The municipal mayor complemented the accounts from community leaders of the villages El Limonero, Fuerte Campesino, and San Juan el Mirador in relating the following story of migration in Fray Bartolomé de las Casas:

An early wave of out-migration from the municipio began in the late 1970s to the mid-1980s with the Ixcán in northern Quiché as a popular destination. But Ixcán filled with settlers in a matter of several years’ time and then rapidly depopulated in the 1980s following widespread violence in the region (see, e.g., Jones, 1990). The next destination for landless farm households became the Ruta a Naranjo, adjacent to the SLNP. According to the municipal mayor, migration there started in earnest around 1987 and was substantial until very recently. Today, as the frontier has become largely closed, some still migrate seasonally to the region to work as farm laborers. The municipal mayor explained that people in Fray understand that on the road to Naranjo each community has a certain number of persons and that they don’t accept further colonization beyond the agreed limit. He noted that, in this regard, the SLNP-area communities are not spontaneously formed at all, as it may appear from the outside, but quite rigidly organized. The mayor estimated that during the past ten years perhaps one-fifth of the households out-migrated permanently from the municipio. Informants in the three communities agreed with the mayor that southern Petén and the Naranjo region in northern Petén were primary areas for permanent out-migration, as well as the municipal capital, Cobán. Unlike Nueva Concepción and Morales, neither Guatemala City nor the United States were mentioned as common destinations.

Why people left

From 1980–1995, a precipitating factor for out-migration was the civil war that hit Fray Bartolomé de las Casas particularly hard. As a result, many people left, with the majority going to the Naranjo area. In that time, the mayor explained, people had sufficient land but were compelled to sell it to flee the violence. Fuerte Campesino exemplifies the impact violence had on out-migration from some of the communities in the municipio. Esaú, a farmer from Fuerte Campesino explained that his village emptied out almost completely in the 1980s. Many left precisely in 1988, Esaú explains, “when land was sold to large farmers.” He continues: “Some had one caballeria of land, others had half a caballeria. People fled troops from both sides.” Of the original 60 families in Fuerte Campesino only five remained. Esaú relates that “people fled to all regions of the country, to Guatemala City, to the south, and to Petén.” Esaú explained that the five families who remained in the village suffered through tough times:

We were surrounded by the army. They would come into the village and label us as guerrillas. They interrogated us. They would ask if we were giving food to the guerrillas and sometimes they pretended to be guerrillas to make sure we were telling the truth.

In San Jose informants concurred that during the late 1980s and early 1990s, and particularly in 1988, violence pushed many residents to permanently out-migrate. At that time many left for Petén. According to one man, “in the north the land is better” which, he claims, is why so many continued to journey to Petén even after the political violence softened in the area in the early 1990s.iv

In more recent years, since the war left the region in the early 1990s, a new reason for migration has emerged: soil degradation. According to the informants in the three communities, farmers complain of the poor soil that now produces only with chemical fertilizers when once natural fertilizer used to be sufficient. But even chemical inputs are no panacea. As one El Limonero maize farmer related, since ten years ago, purchased fertilizers have been necessary and these have “burned the soil.” Similarly, in Fuerte Campesino, a man noted how soil degradation and poverty have ignited a vicious cycle: “People need money before they can rent land to make enough money from crops to buy inputs.” He lamented that he didn’t even make enough “to spread ‘poison’ on [his] crops”, and that only by doing so would he make enough to buy his own farm. Even in San Jose, where there is relatively abundant farmland, soil quality has worsened and informants complained that most lack the money to apply inputs, especially renters who typically farm just one manzana in subsistence maize cultivation.

Where people went

Whereas Petén was the place to escape violence in the 1980s, recent migrants have ventured to Petén to acquire a farm or a bigger and better farm than the one presently owned. One informant noted that the “poor land [in Fray] doesn’t produce without fertilizer” while “in Petén you don’t need fertilizer.” Thus, migration to the Naranjo area in Petén has occurred not only because of the violence but, as one community leader explained, “to make more money selling crops because in Fray it didn’t pay enough. Maize in Fray is just for subsistence.” This is largely because land availability allows for increased production even though farmers make somewhat less per pound of crop sold in Petén. He notes that, “even without land, laborers make more money there, up to Q40/day”. That is why, he explained, “even with land in Fray, people go for ten or twenty days to Petén to work.”

Informants in each community agreed that those who venture to Petén often do so with the notion of acquiring their own farm and many travel there permanently whereas work in the capital is almost always temporary. They further concurred that people that go to Guatemala City, even temporarily, tend to be better educated or have some job skills appropriate for the urban environment. Conversely, those who settle the Petén frontier tend to be less educated and to have few skills besides subsistence farming and manual labor on ranches and large farms. One informant summed up this sentiment by explaining that “for poor farmers without land Petén is the best place but if they are educated it is better to go to Guatemala City to find work.” In Fuerte Campesino, he continued, “people without land are the ones that go to Petén most. But, he explained, “some leave because they want more land.”

In Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, a maize “gold rush” filled the region in less than a generation. As land became scarce through rapid in-migration and land consolidation, civil war violence erupted in the region, catalyzing massive out-migration to the next frontier of Petén. More recently, many farm plots have become degraded over time sufficiently to render them barely adequate for subsistence. This has occurred even though land availability is much better than in other areas of the country. But lack of temporary jobs in the area and, therefore, lack of capital to purchase inputs, has contributed to soil fertility declines.

It is the farmers who have been least able to cope with these changes that were most likely to migrate to Petén. As the municipal mayor bemoans, “Now people from away have come here to look for land because there is no more land available in other parts of the country but it is all taken here too and our own poor are moving out.” Unfortunately, as in Fray by the 1980s, the colonization frontiers of Petén no longer offer an adequate escape valve for land-impoverished families.

Conclusion

A common denominator among communities of migration origin to the Petén frontier was unequal resource access, usually land. Despite the common thread of resource inequalities, resource access became skewed and scarce for the majority in different municipios for different reasons. Population growth and environmental degradation were factors of varying magnitude in spurring out-migration from each of the three municipios presented here. Whereas these conditions were sufficient for out-migration, violence was a catalyst in the 1980s that sent substantial flows of migrants searching for land and peace in several villages throughout the regions in the study, but most notably in Fray Bartolomé de las Casas. Lastly, land consolidation was a major force in Morales and Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, but was entirely absent in Nueva Concepción, suggesting that any one factor—land degradation, land consolidation, or population growth—may be sufficient to erode living standards and compel out-migration.

Despite these conditions, most people in the communities studied did not out-migrate, suggesting that any one or combination of factors is not necessarily sufficient for out-migration. And of those who did, only a minority settled the open forests along Petén’s expanding agricultural frontiers. Rural-frontier migration was relatively rare even in the sampled regions of high out-migration to the Petén frontier. Yet this rare occurrence was responsible for most of the deforestation that has eliminated nearly half of Petén’s once vast forests since the 1960s. Other sources of forest clearing, growing cattle ranching, and substantial commercial logging and petroleum extraction in the region, are linked to peasant migration and to road construction, which allows peasants access to forested areas. While these other land change processes ultimately may overtake small-scale farming as the primary direct cause of deforestation, consistent with forest transition theory (e.g., Mather 1992; Rudel 2002) small farmers nearly always cleared the forest first following road construction.

Similar processes operating in rural areas throughout the developing world are prerequisite to the driving demographic force behind most of the planet’s deforestation. Population and land use researchers could fruitfully pursue this line of research, to the benefit of policy aimed at rural development and forest conservation.

Policy prescriptions must be sensitive to place. Despite the common denominator of resource access inequalities, inequalities evolved for different reasons in different places. Population growth and environmental degradation spurred out-migration from each of the three municipios presented as case studies. These conditions were sufficient for out-migration, but violence was a catalyst in the 1980s that sent some migrants searching for land in several municipios, most notably in Fray Bartolomé de las Casas. Lastly, land consolidation was a major force in Morales and Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, but was entirely absent in Nueva Concepción, suggesting that any one factor—land degradation, land consolidation, or population growth—may be sufficient to foster out-migration. Therefore, blanket prescriptions implemented in origin areas encouraging smaller family size through promoting reproductive health, land redistribution, or relieving pressures through colonization may be doomed to failure on their own, especially in places where those are not the primary problems.

Acknowledgments

The following sources of funding were instrumental in the development of this research article: UCSB Senate Faculty Research Grant, National Institutes of Health Career Development Award (K01: HD049008), National Science Foundation Geography and Regional Science grant (BCS-0525592), UCSB Faculty Career Development Award, The Mellon Foundation, Social Science Research Council, Fulbright-Hays Foundation, NASA, The Rand Corporation, Institute for the Study of World Politics, University of North Carolina Royster Society of Fellows, The Carolina Population Center, and The Nature Conservancy.

Footnotes

In many developing countries, rural-rural migration is far more important than commonly supposed. In a recent review of existing data by the UN, of the 14 developing countries which have census data on internal migration, in which both the origin and destination are classified as rural or urban (censuses from 1966 to 1995), rural-urban migration was largest in only 2 countries and rural-rural in 3 (urban-urban being largest overall). Rural-rural flows were larger than rural-urban in 10 of the 14 countries (UN, 2001, p. 66).

6.1 births per woman, according to the Guatemalan National Institute of Statistics Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (1999). Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos. Guatemala‥

Using data from the latest (1993) population census, I defined migrants as persons living in the municipio of La Libertad, the county in which the SLNP is situated (occupying most of the municipio’s territory) at the time of the census who had ever lived in another municipio. Most migrants to the municipio of La Libertad during the decade prior to the census migrated to the SLNP.

Unlike Fuerte Campesino and San Jose, El Limonero was not largely depopulated from the war. On the contrary, El Limonero was formed by 400 returned refugees who were displaced from other war-torn regions of the country. Former President Lucas sold a farm, and returnees from the Mexican states of Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Chiapas arrived there under the auspices of the UN High Commisioner for Refugees. They were given the option to move there or to La Unión Maya Itzá in the SLNP. An informant from El Limonero claimed that he didn’t like La Unión because it is far from Flores, whereas El Limonero is much closer to the municipal capital of Fray (10 km.). He explained that “in [the refugee camp] in Campeche we were shown maps and village plans and we could go to whichever we wished. It is better here because it is not difficult to transport our produce. Up there [in the SLNP] it is difficult to bring [produce] to market in Flores.”

References Cited

- Aguayo S, Christensen H, O'Dogherty L, Varese S. Social and Cultural Conditions and Prospects of Guatemalan Refugees in Mexico. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier EB. Links between economic liberalization and rural resource degradation in the developing regions. Agricultural Economics. 2000;23(3):299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D. Environmental refugees? Classifying human migrations caused by environmental change. Population and Environment. 2002;23(5):465–477. [Google Scholar]

- Bible DS, Brown LA. Place utility, attribute tradeoff, and choice behavior in an intra-urban migration context. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 1981;15(1):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow RE, Mc Devitt TM, Kossoudji S, Fuller R. The impact of origin community characteristics on rural-urban out-migration in a developing country (Ecuador) Demography. 1987;24(2):191–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow RE, Geores M. Rural Population Dynamics and Agricultural Development: Issues and Consequences Observed in Latin America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell International Institute for Food, Agriculture and Development; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow RE, Stupp P, Bixby LR, Pebley A, Mendez AB. Demographic Diversity and Change in the Central American Isthmus. Santa Monica, Rand: 1997. Demographic processes, land, and environment in Guatemala; pp. 581–624. [Google Scholar]

- Beavers J. Tenure and Forest Exploitation in the Peten and Franja Transversal del Norte Regions of Guatemala. World Bank, Guatemala and Natural Resource and Management Study; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Sierra R. Frontier migration as a multi-stage phenomenon reflecting the interplay of macroforces and local conditions: the Ecuador Amazon. Papers in Regional Science. 1994;73(3):267–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1435-5597.1994.tb00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DL. Un perfíl socioeconómico y demográfico del Parque Nacional Sierra de Lacandón. In: Grunberg J, Elias S, editors. Nuevas Perspectivas de Desarrollo Sostenible en Petén. Guatemala City, Guatemala: Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO); 2000. pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Carr DL. 10 Tiempos de America: Revista de Historia, Cultura y Territorio. Centro de Investigaciones de America Latina (CIAL), Universitat Jaume I; 2003. Migracion rural-rural y deforestacion en Guatemala: Método de Entrevistas; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carr DL. Population, land use, and deforestation in the Sierra de Lacandón National Park, Petén, Guatemala. The Professional Geographer. 2005;57(2):157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. Land tenure delegitimation and social mobility in tropical Péten, Guatemala. Human Organization. 2000;59(4):419–427. [Google Scholar]

- Curran S, Rivero-Fuentes E. Engendering migrant networks: the case of Mexican migration. Demography. 2003;40(2):289–307. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Stecklov G, Winters P. Domestic and international migration from rural Mexico: disaggregating the effects of network structure and composition. Population Studies. 2002;56(3):291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ezra M, Kiros G. Rural out-migration in the drought prone areas of Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. International Migration Review. 2001;35(3):749–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2001.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley AM, Li F. Methodological Issues in Researching Migration. The Professional Geographer. 1999;51(1):50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Findley SE. Does drought increase migration? A study of rural migration from Mali during the 1983–1985 drought. International Migration Review. 1994;28(53953) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenn N. Community Formation in Frontier Mexico: Accepting and Rejecting New Migrants. Human Organization. 1999;58(1):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Henry S, Schoumaker B. The impact of rainfall on the first out-migration: a multi-level event-history analysis in Burkina Faso. Population and Environment. 2004;25(5):423–460. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos. Guatemala: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JR. Colonization and Environment: Land Settlement Projects in Central America. Tokyo: United Nations University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Katz EG. Social Capital and Natural Capital: A Comparative Analysis of Land Tenure and Natural Resource Management in Guatemala. Land Economics. 2000 Feb.Vol. 76(No 1):114–132. [Google Scholar]

- Laurian L, Bilsborrow RE, Murphy L. Migration decisions among settler families in the Ecuadorian Amazon: the second generation. Research in Rural Sociology and Development. 1998;7:169–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH. Why People Intend to Move: Individual and Community-Level Factors of Out-Migration in the Phillippines. Boulder and London: Westview; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS. The forest transition. Area. 1992;24(4):367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Milián B, Grünberg G, Cho-Botzoc M. La conflictividad agraria en las Tierras bajas del norte de Guatemala: Petén y la franja transversal del Norte. Guatemala City, Guatemala: FLACSO-MINUGUA-CONTIERRA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Social Structure, Household Strategies, and the Cumulative Causation of Migration. Population Index. 1990;56(1):3–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AR, May RA. Escape from Terror: Violence and Migration in Post-Revolutionary Guatemala. Latin American Research Review. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Pebley AR. Demography and the Environment. Demography. 1998;35(4):377–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichón FJ. Land-Use Strategies in the Amazon Frontier: Farm-Level Evidence from Ecuador. Human Organization. 1996;55(4) [Google Scholar]

- Premo DL. Political Assassination in Guatemala: A Case of Institutionalized Terror. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 1981;23(4):429–456. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel TK. When do property rights matter: Open access, informal social controls, and deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Human Organization. 1995;54(2):187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel TK, Bates D, Machinguiashi R. A Tropical Forest Transition? Agricultural Change, Out-migration, and Secondary Forests in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2002;92(1) [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz N, Painter M, Durham WH. The Social Causes of Deforestation in Latin America. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1995. Colonization, Development and Deforestation in Petén, Northern Guatemala; pp. 101–130. [Google Scholar]

- SEGEPLAN. Agricultura, Población y Empleo en Guatemala. Guatemala City: SEGEPLAN (Secretaria General del Consejo Nacional de Planificación Económica); 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Southgate D. The Causes of Land Degradation along "Spontaneously" Expanding Agricultural Frontiers in the Third World. Land Economics. 1990;66(1):93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Stonich S. The dynamics of social processes and environmental destruction: a Central American case study. Population and Development Review. 1989;15(2):269–297. [Google Scholar]

- Stonich S. I am Destroying the Land!: The Political Ecology of Poverty and Environmental Destruction in Honduras. Boulder, Co: Westview Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Verduzco G. Estudios Sociológicos. No 39. Vol. XIII. El Colegio de México, México: 1995. Sept.–Dec., La migración mexicana a Estados Unidos: Recuento de un proceso histórico; pp. 573–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanWey L. Land ownership as a determinant of temporary migration in Nang Rong, Thailand. European Journal of Population. 2003;19(2):121–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert J. Behavioral Aspects of the Decision to Migrate. Papers and Proceedings of the Regional Science Association. 1965;15:159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert J. Migration as an Adjustment to Environmental Stress. Journal of Social Issues. 1966;22:92–102. [Google Scholar]