Abstract

Stigma can be a major stressor for individuals with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. It is unclear, however, why some stigmatized individuals appraise stigma as more stressful, while others feel they can cope with the potential harm posed by public prejudice. We tested the hypothesis that the level of perceived public stigma and personal factors such as rejection sensitivity, perceived legitimacy of discrimination and ingroup perceptions (group value; group identification; entitativity, or the perception of the ingroup of people with mental illness as a coherent unit) predict the cognitive appraisal of stigma as a stressor. Stigma stress appraisal refers to perceived stigma-related harm exceeding perceived coping resources. Stress appraisal, stress predictors and social cue recognition were assessed in 85 people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective or affective disorders. Stress appraisal did not differ between diagnostic subgroups, but was positively correlated with rejection sensitivity. Higher levels of perceived societal stigma and holding the group of people with mental illness in low regard (low group value) independently predicted high stigma stress appraisal. These predictors remained significant after controlling for social cognitive deficits, depressive symptoms and diagnosis. Our findings support the model that public and personal factors predict stigma stress appraisal among people with mental illness, independent of diagnosis and clinical symptoms. Interventions that aim to reduce the impact of stigma on people with mental illness could focus on variables such as rejection sensitivity, a personal vulnerability factor, low group value and the cognitive appraisal of stigma as a stressor.

Keywords: stigma, stress, cognitive appraisal, rejection sensitivity, perceived legitimacy of discrimination, ingroup perception, group value

1. INTRODUCTION

Stigma is a major stressor for many people with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses (Corrigan, 2005; Hinshaw, 2007; Link and Phelan, 2001; Thornicroft, 2006). It is unclear, however, why some people with mental illness remain relatively unaffected by stigma whereas others perceive stigma as more stressful and are demoralized, with often serious clinical consequences (Corrigan and Watson, 2002; Rüsch et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2007). Social psychological research on other stigmatized groups that used a stress and coping framework (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) offers a promising model to investigate the range of perceptions of and responses to mental illness stigma (Major et al., 2002b; Miller and Major, 2000; Miller, 2006). Identifying vulnerability and resilience factors to stigma stress can help to reduce stigma’s impact on persons with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. Considerable research examined stress-reactivity in schizophrenia (Betensky et al., 2008; Horan et al., 2005; Myin-Germeys and van Os, 2007). A related line of work studied how people with schizophrenia cope with their illness and other stressors (Cooke et al., 2007; Lysaker et al., 2004, 2005; Roe, 2001, 2006). Building on this important work and applying a social-psychological stress-coping model to mental illness stigma, we specifically investigated stigma-related stress.

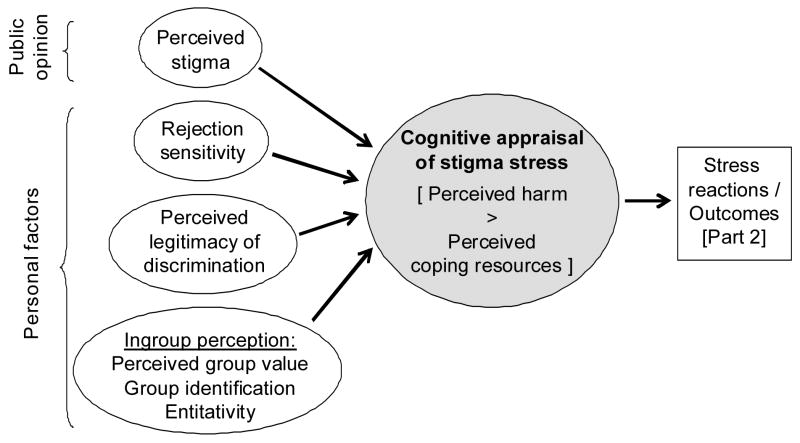

The stress-coping model examined in this study (Major and O’Brien, 2005) includes four elements of stigma and its impact on individuals with mental illness, (1) public and personal factors that predict the appraisal of stigma as stressful; (2) the cognitive appraisal of stigma stress itself; (3) emotional and cognitive responses to stigma stress; and (4) outcome variables that are influenced by stress responses. The first two elements, stigma stress appraisal and its predictors, shall be discussed in part 1 of this two-part paper (Figure 1); stress reactions and outcomes are the subject of part 2 (Rüsch et al., submitted).

Figure 1.

Cognitive appraisal of stigma-related stress and its predictors (part 1, adapted from Major and O’Brien, 2005). Stress predictors consist of public and personal factors (left margin of Figure 1). Ingroup perception (lower left corner of Figure 1) refers to how individuals with mental illness perceive their ingroup, that is the group of people with mental illness; more specifically, how individuals value their ingroup (group value), how strongly they feel attached to it (group identification) and whether they perceive their ingroup as a coherent unit in society (entitativity).

The cognitive appraisal of stigma-related stress is the key element of this model (Figure 1). For example, persons with schizophrenia experience stigma-related stress when they fear losing their job or apartment due to public prejudice and believe they do not have the resources to overcome this threat. Two types of cognitive appraisals are relevant here (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). In primary appraisal, a person estimates the potential harm resulting from stigma; in secondary appraisal, individuals estimate their personal resources to cope with stigma. Thus, stigma stress is a difference score of primary and secondary appraisal and occurs when perceived harm exceeds perceived coping resources.

Public and personal factors predict why some people with mental illness perceive stigma as stressful but others do not (Figure 1; Major and O’Brien, 2005). As a public factor, the more stigma individuals with mental illness perceive in society, the more likely they are to see stigma as potentially harmful (Crocker et al., 1998). Social cognition needs to be taken into account as a specific factor in mental illness, because social cognitive deficits are common in schizophrenia (Corrigan and Penn, 2001) and stigma must be perceived by the stigmatized person in order to act as a stressor. Such deficits may reduce the level of perceived stigma if individuals fail to pick up subtle stigmatizing behavior and cues, or could cause a person to misunderstand neutral behavior in others as stigmatizing. In terms of personal characteristics we studied three factors that shape stress appraisal (Figure 1). First, people with mental illness can be sensitive to rejections in personal relationships which renders them more vulnerable to stigma leading to higher stress appraisal. A person with schizophrenia who is highly concerned about being rejected by neighbors or work colleagues is more vulnerable to perceive stigma as a stressor (Jussim et al., 2000; Downey and Feldman, 1996; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002). Second, stigmatized individuals are often motivated to believe that society is fair and therefore perceive stigma as legitimate which, although not improving the person’s or the group’s status, can subjectively ease stigma-related stress (Jost et al., 2003; Major et al., 2002a). Third, how people with mental illness value and perceive their ingroup (i.e., people with mental illness) likely influences stress appraisals because public stigma targets them as members of their group. A recent review summarized three factors that influence an ingroup’s impact on group members (Correll and Park, 2005): whether group members evaluate their ingroup positively or negatively (perceived group value); how strongly individuals identify with their group (group identification; Jetten et al., 2001; Watson et al., 2007); and entitativity, or the perception of the ingroup as a coherent and meaningful unit (Campbell, 1958; Lickel et al., 2000). Ingroup perception is relevant because individuals who hold their group in high regard (high group value) are more immune to stigma; and those who do not feel close to their group (low group identification) or see the group as incoherent (low entitativity) will perceive stigma as less personally relevant and therefore as less stressful (Corrigan and Watson, 2002; Correll and Park, 2005).

We examined a stress-coping model of stigma to better understand how stigma affects people with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses which could eventually lead to improved interventions and outcomes for individuals affected by stigma-related stress. In part 1 of this study, we tested the hypothesis that more perceived stigma, more rejection sensitivity, less perceived legitimacy of discrimination and ingroup perception variables (lower perceived group value, more group identification, more entitativity) predict the appraisal of stigma as more stressful.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

Eighty-five participants with mental illness were recruited from centers offering mental health services in the Chicago area as a representative group of people with chronic and serious mental illness in outpatient settings. This sample size allowed us to examine several variables as stress predictors, including diagnosis. An eighth grade reading level as assessed by the Wide Range Achievement Test (Wilkinson and Robertson, 2006) was required. All participants gave written informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Illinois Institute of Technology and the collaborating organizations. Participants were on average about 45 years old (M=44.8, SD=9.7), had a mean of 13.5 years of education (SD=2.3) and were 68% male. More than half (58%) were African-American and about a third (34%) Caucasian, while a few reported Hispanic or Latino (5%) and mixed or other ethnicities (4%). Axis I diagnoses were made using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) based on DSM-IV criteria. Twenty-three (27%) participants had schizophrenia, 22 (26%) schizoaffective disorder, 30 (35%) bipolar I or II disorder, and 10 participants (12%) had recurrent unipolar major depressive disorder. In addition, in the entire sample 33 subjects (39%) had comorbid current alcohol- or substance-related abuse or dependence. On average, participants with mental illness were first diagnosed about 15 years ago (M=14.9, SD=10.2) and had been hospitalized in psychiatric institutions about nine times (M=9.2, SD=13.1).

2.2. Cognitive appraisal of stigma-related stress

Adapting a measure of cognitive appraisal of sexism (Kaiser et al., 2004) that was based on Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) conceptualization of stress appraisal processes, four items assessed primary appraisal of mental illness stigma as personally harmful (e.g., “Prejudice against people with mental illness will have harmful or bad consequences for me”) (Cronbach’s alpha=.88). Four additional items measured secondary appraisal of perceived resources to cope with stigma (e.g., “I have the resources I need to handle problems posed by prejudice against people with mental illness”) (Cronbach’s alpha=.78). All eight items were scored from 1 to 7 with higher scores equaling higher agreement. A single stress appraisal score was computed by subtracting perceived resources from perceived harmfulness. A higher difference score indicated the appraisal of stigma as stressful and as exceeding personal coping resources.

2.3. Measures of perceived stigma, legitimacy, rejection sensitivity and depression

Link’s (1987) 12-item Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Questionnaire was used to measure the perceived level of stigma against persons with mental illness in society, higher scores reflect more perceived stigma (Cronbach’s alpha=.85). Perceived legitimacy of discrimination is defined as an individual’s perception that their ingroup’s lower status in the social hierarchy is fair. It was assessed with three items adapted from Schmader and coworkers (2001) such as ‘Do you think it is justified that people without a mental disorder have a higher status than people with a mental disorder?’. Higher scores reflected higher perceived legitimacy (Cronbach’s alpha=.82). The Adult Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire, developed by Downey and colleagues (Downey and Feldman, 1996; http://www.columbia.edu/cu/psychology/socialrelations/), was used to measure rejection sensitivity in personal relationships. An average score across nine scenarios was calculated by multiplying the level of rejection concern with the expected likelihood of rejection for each scene (Cronbach’s alpha=.81), with higher scores indicating more rejection sensitivity. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977) with higher scores indicating representing higher levels of depression.

2.4. Ingroup perception measures

Perceived value of the group of people with mental illness in terms of valence and power was measured by two items: “I think the group of people with mental illness is … very bad/very good” and “… not powerful at all/very powerful” (from 1 to 9). The split-half reliability of this scale was satisfactory (0.74 according to the Spearman Brown formula, the equivalent of Cronbach’s alpha for two-item scales; Hulin, 2001), with higher mean scores indicating higher perceived value of the ingroup (Rüsch et al., unpublished manuscript). Identification with the group of people with mental illness was conceptualized by five items adapted from Jetten and colleagues (2001), e.g. ‘I feel strong ties with the group of people with mental illness’ (Cronbach’s alpha=.85). Items were rated from 1 to 7, with higher mean scores indicating higher group identification. Entitativity refers to the perception of a group as a meaningful and coherent entity (Campbell, 1958; Lickel et al., 2000). After introducing participants to the concept of entitativity (Rüsch et al., unpublished manuscript), four items, scored from 1 to 9, measured perceived entitativity of people with mental illness such as ‘People with mental illness can be recognized as a distinct group in larger society’ (Cronbach’s alpha=.73).

2.5. Social Cue Recognition

We used a shortened version of the Social Cue Recognition Test (Corrigan and Green, 1993) to measure social cognitive deficits which may affect stigma perception. On a computer screen participants watched a short vignette in which a man and a woman interacted. Afterwards participants responded to 36 true-false questions about the content of the scene. Half of the questions referred to concrete cues (“George came into the room through the door”), the other half to abstract cues about goals and motives (“In this situation, George’s goal is to help Laurie out”). Hits and false positive responses were recorded separately for concrete and abstract cues. Previous research indicates that the number of false positive responses to abstract cues is the most sensitive indicator of social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia (Corrigan and Nelson, 1998; Corrigan and Green, 1993) and was therefore used as index of social cognitive deficits.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cognitive stress appraisal and its predictors across diagnostic groups

We examined differences in levels of cognitive stress appraisal and stress predictors between the four groups of subjects with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. Analyses of variance did not indicate significant group effects, except for rejection sensitivity (F=4.80, p=.004) and social cognition (false positive responses in the Social Cue Recognition Test, F=4.26, p=.008). Post-hoc Scheffé tests showed significantly lower rejection sensitivity in the schizophrenia (M=10.1, SD=3.8) than in the bipolar (M=14.2, SD=5.5; p=.03) and the unipolar depression groups (M=16.2, SD=5.7; p=.02). Social cognition was worse in the schizophrenia group (M=2.4, SD=1.5) than in the bipolar group (M=1.2, SD=1.2; p=.03). Other subgroup differences were non-significant. Subjects with versus without substance- or alcohol related disorders in the entire sample did not differ in terms of predictors or stress appraisal (p-values >.20).

3.2. Correlations between predictors and cognitive stress appraisal

Higher levels of perceived stigma were associated with cognitive appraisal of stigma as more stressful. Because stress appraisal is a difference score between the primary appraisal of stigma’s perceived harmfulness and the secondary appraisal of perceived resources to cope with stigma, correlations of stress predictors with primary and secondary appraisals were assessed as well (Table 1). This gave us a better understanding whether correlations with the stress appraisal difference score extended to the underlying primary and secondary appraisals. A higher level of perceived public stigma was associated with regarding stigma as more harmful, but not with perceived coping resources (Table 1). More rejection sensitivity was also associated with higher perceived stigma stress, but unlike perceived stigma, rejection sensitivity was related to lower perceived coping resources. Perceiving stigma as unfair (low perceived legitimacy of discrimination) was associated with more perceived harm due to stigma; however, it was not correlated with perceived resources or stress. High group value was related to more perceived resources to cope with stigma, but was not significantly correlated with stigma stress in bivariate correlations. Interestingly, group identification and entitativity were positively related to both perceived harm and to perceived coping resources. Since stress appraisal is a difference score between perceived harm and coping resources, these associations seemed to cancel each other out, resulting in the lack of correlations with stress appraisal. Social cognition (false positives in the Social Cue Recognition Test) was not related to stress appraisal (r=−.13, p=.25), but poorer social cognition was associated with two stress predictors, less perceived stigma (r=−.32, p=.003) and less rejection sensitivity (r=−.29, p=.008).

Table 1.

Correlations between predictors (left column) and cognitive appraisal of stigma stress (top row)

| Appraisal of stigma stressa | Appraisal of stigma as harmful | Appraisal of resources to cope with stigma | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived stigmab | .36 ** | .42 ** | −.08 |

|

| |||

| Rejection sensitivityc | .27 * | .14 | −.27 * |

|

| |||

| Perceived legitimacy of discrimination | −.15 | −.26 * | −.08 |

|

| |||

| Perceived group value | −.13 | .06 | .29 ** |

|

| |||

| Group identification | .08 | .33 ** | .27 * |

|

| |||

| Entitativityd | .09 | .35 ** | .27 * |

p <.05

p <.01 (two-tailed)

Difference score of ‘appraisal of stigma as harmful’ (primary appraisal) minus ‘appraisal of resources to cope with stigma’ (secondary appraisal). Higher scores indicate higher perceived stigma-related stress, that is perceived harm of stigma exceeds perceived resources to cope with stigma

Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Questionnaire (Link, 1987)

Adult Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (Downey and Feldman, 1996)

Higher entitativity scores indicate a stronger perception of the group of people with mental illness as a coherent and meaningful unit

3.3. Regression on cognitive stress appraisal

In order to investigate whether univariately significant predictors of stress appraisal acted independently, we calculated a multivariate regression on stress appraisal with six predictors (Table 2, Figure 1) which were only moderately interrelated (all correlation coefficients <.50). More perceived stigma in society, lower group value (holding one’s ingroup in low regard) and, at a trend level, higher rejection sensitivity independently predicted the appraisal of stigma as stressful. We then repeated the regression controlling for possible confounds of depressive symptoms, social cognitive deficits and diagnosis (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; because the subgroup comparisons had not shown any significant group differences between the schizophrenia and schizoaffective groups, both were collapsed into one diagnostic category and contrasted with affective disorders as a dummy variable). In a regression with these three variables as additional predictors none of them were significant and R2 did not increase; perceived stigma and group value remained significant predictors of stress appraisal (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regressions on cognitive appraisal of stigma stress

| Dependent variable | Independent variables | Beta | T | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appraisal of stigma stressa | Perceived stigmab | 0.32 | 3.00 | .004 | .23 |

| Rejection sensitivityc | 0.19 | 1.72 | .09 | ||

| Perceived legitimacy of discrimination | −0.11 | −1.04 | .30 | ||

| Perceived group value | −0.22 | −2.02 | .047 | ||

| Group identification | 0.18 | 1.46 | .15 | ||

| Entitativityd | 0.03 | .24 | .81 | ||

|

| |||||

| Appraisal of stigma stressa | Perceived stigmab | 0.29 | 2.49 | .015 | .23 |

| Rejection sensitivityc | 0.16 | 1.26 | .21 | ||

| Perceived legitimacy of discrimination | −0.12 | −1.04 | .30 | ||

| Perceived group value | −0.23 | −2.01 | .048 | ||

| Group identification | 0.20 | 1.52 | .13 | ||

| Entitativityd | 0.02 | 0.15 | .88 | ||

| Social cue recognitione | −0.02 | −0.12 | .90 | ||

| Depressive symptomsf | 0.08 | 0.62 | .54 | ||

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 0.01 | 0.02 | .98 | ||

Difference score of ‘appraisal of stigma as harmful’ minus ‘appraisal of resources to cope with stigma’. Higher scores indicate higher perceived stigma-related stress, i.e. perceived harm exceeding perceived resources

Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination Questionnaire (Link, 1987)

Adult Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (Downey and Feldman, 1996)

Higher entitativity scores indicate a stronger perception of the group of people with mental illness as a coherent and meaningful unit

Social Cue Recognition Test, number of false positives for abstract cues (Corrigan and Green, 1993)

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977)

4. DISCUSSION

We tested a social psychological stress-coping model of stigma (Major and O’Brien, 2005) among persons with schizophrenia, schizoaffective or affective disorders. According to the model, the level of perceived public stigma and personal variables predict whether stigmatized individuals appraise stigma as stressful, exceeding their perceived coping resources. This hypothesis was partly supported by our findings. The level of perceived stigma was a strong predictor of stress appraisal. This highlights the urgency to reduce public stigma to reliably decrease perceived stigma and its consequence, stigma-related stress for stigmatized individuals.

Based on low perceived coping resources, the link between rejection sensitivity and stigma stress supports previous research that rejection sensitivity can exacerbate stigma stress by undermining perceived social support (Jussim et al., 2000; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002). Rejection sensitivity is therefore a worthwhile target for initiatives aiming to reduce stigma’s impact on individuals. Low perceived group value as a stress predictor implies that only a valued ingroup is a resource for group members (Correll and Park, 2005; McCoy and Major, 2003). Interestingly, group identification and entitativity were related to both perceiving stigma as more harmful and to more perceived coping resources. This is plausible because for someone who feels attached to a coherent group, group membership can be a resource or a threat, depending on, for example, situational cues or group value (Correll and Park, 2005). As expected and consistent with system justification theory, high perceived legitimacy of discrimination was associated with seeing stigma as less harmful (Jost et al., 2003; Major et al., 2002a); however, this did not extend to stigma stress appraisal.

Social cognitive deficits, though not directly linked to stigma stress, seem to reduce the level of public stigma that individuals perceive and may therefore indirectly reduce stigma stress. Future studies should investigate this issue using structural equation modeling in larger samples. Psychiatric diagnoses and depressive symptoms, on the other hand, did not play a major role in our results. This is consistent with stigma as a stressor for people with serious mental illness in general, independent of diagnosis.

Before drawing conclusions, limitations of our study have to be considered. First, our data are cross-sectional and therefore cannot determine causality; thus more stigma stress could also influence predictors. Longitudinal studies should investigate the direction of causal relationships and possible feedback loops between predictors and stress appraisal. Second, stigma stress is often related to situational threats which were not examined by our trait-measures. Future work should study the relationship between stigma and other stressors in schizophrenia (Betensky et al., 2008; Myin-Germeys and van Os, 2007).

Despite these limitations we found support for public and personal factors as predictors of cognitive stress appraisal in response to mental illness stigma. Perceived stigma as a predictor of stigma stress underscores the importance of reducing public stigma to improve the situation of individuals with mental illness (Corrigan and Penn, 1999; Rüsch et al., 2005). Group value, the other major factor associated with stigma stress, could be a useful target for interventions that aim to reduce the impact of stigma, whether in group trainings run by professionals (Knight et al., 2006) or in peer-support programs (Clay et al., 2005), and recently gained increasing attention. Targeting group value and rejection sensitivity, such approaches could ease stigma-related stress and increase resilience to public stigma. Part 2 of this study will discuss reactions to stigma stress and how it affects broader outcomes, identifying further targets for such interventions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Betensky JD, Robinson DG, Gunduz-Bruce H, Sevy S, Lencz T, Kane JM, Malhotra AK, Miller R, McCormack J, Bilder RM, Szeszko PR. Patterns of stress in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2008;160:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT. Common fate, similarity, and other indices of the status of aggregates of persons as social entities. Behavioral Science. 1958;3:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW, Ralph RO. On our own, together: Peer programs for people with mental illness. Vanderbilt University Press; Nashville: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke M, Peters E, Fannon D, Anilkumar AP, Aasen I, Kuipers E, Kumari V. Insight, distress and coping styles in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;94:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll J, Park B. A model of the ingroup as a social resource. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:341–359. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0904_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. American Psychological Association; Washington: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Green MF. Schizophrenic patients’ sensitivity to social cues: The role of abstraction. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:589–594. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Nelson DR. Factors that affect social cue recognition in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 1998;78:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Social cognition and schizophrenia. American Psychological Association Press; Washington: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist. 1999;54:765–776. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. The mark of shame: Stigma of mental illness and an agenda for change. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Hwang SS, Mintz J. Stressful life events in recent-onset schizophrenia: reduced frequencies and altered subjective appraisals. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;75:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulin C. Cronbach’s alpha on two-item scales. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2001;10:55. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J, Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Spears R. Rebels with a cause: Group identification as a response to perceived discrimination from the mainstream. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1204–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Pelham BW, Sheldon O, Sullivan BN. Social inequality and the reduction of ideological dissonance on behalf of the system: Evidence of enhanced system justification among the disadvantaged. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2003;33:13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Palumbo P, Chatman C, Madon S, Smith A. Stigma and self-fulfilling prophecies. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The social psychology of stigma. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 374–418. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CR, Major B, McCoy SK. Expectations about the future and the emotional consequences of perceiving prejudice. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:173–184. doi: 10.1177/0146167203259927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MTD, Wykes T, Hayward P. Group treatment of perceived stigma and self-esteem in schizophrenia: A waiting list trial of efficacy. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;34:305–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lickel B, Hamilton DL, Wieczorkowska G, Lewis A, Sherman SJ, Uhles AN. Varieties of groups and the perception of group entitativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:223–246. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Bryson GJ, Marks K, Greig TC, Bell MD. Coping style in schizophrenia: associations with neurocognitive deficits and personality. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:113–121. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Davis LW, Lightfoot J, Hunter N, Stasburger A. Association of neurocognition, anxiety, positive and negative symptoms with coping preference in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;80:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Gramzow RH, McCoy SK, Levin S, Schmader T, Sidanius J. Perceiving personal discrimination: the role of group status and legitimizing ideology. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2002a;82:269–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Quinton WJ, McCoy SK. Antecedents and consequences of attributions to discrimination: Theoretical and empirical advances. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press; San Diego: 2002b. pp. 251–330. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SK, Major B. Group identification moderates emotional responses to perceived prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:1005–1017. doi: 10.1177/0146167203253466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, Pietrzak J. Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African American students’ college experience. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2002;83:896–918. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT. Social psychological perspectives on coping with stressors related to stigma. In: Levin S, van Laar C, editors. Stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah: 2006. pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Major B. Coping with stigma and prejudice. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, editors. The social psychology of stigma. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 243–272. [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, van Os J. Stress-reactivity in psychosis: evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roe D. Progressing from patienthood to personhood across the multidimensional outcomes in schizophrenia and related disorders. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2001;189:691–699. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe D, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH. Coping with psychosis: An integrative developmental framework. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2006;194:917–924. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000249108.61185.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry. 2005;20:529–539. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Powell K, Rajah A, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, Batia K. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: II. Emotional stress responses, coping behavior and outcome. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;110:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Lieb K, Bohus M, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma, empowerment, and perceived legitimacy of discrimination among women with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:399–402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T, Major B, Eccleston CP, McCoy SK. Devaluing domains in response to threatening intergroup comparisons: Perceived legitimacy and the status value asymmetry. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2001;80:782–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G. Shunned: Discrimination against people with mental illness. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT4) Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, Florida: 2006. [Google Scholar]