Abstract

The purpose of this study was to test a conceptual model predicting children's externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten in a sample of children with alcoholic (n = 130) and nonalcoholic (n = 97) parents. The model examined the role of parents' alcohol diagnoses, depression, and antisocial behavior at 12–18 months of child age in predicting parental warmth/sensitivity at 2 years of child age. Parental warmth/sensitivity at 2 years was hypothesized to predict children's self-regulation at 3 years (effortful control and internalization of rules), which in turn was expected to predict externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten. Structural equation modeling was largely supportive of this conceptual model. Fathers' alcohol diagnosis at 12–18 months was associated with lower maternal and paternal warmth/sensitivity at 2 years. Lower maternal warmth/sensitivity was longitudinally predictive of lower child self-regulation at 3 years, which in turn was longitudinally predictive of higher externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten, after controlling for prior behavior problems. There was a direct association between parents' depression and children's externalizing behavior problems. Results indicate that one pathway to higher externalizing behavior problems among children of alcoholics may be via parenting and self-regulation in the toddler to preschool years.

Keywords: alcoholism, parenting, self-regulation, externalizing behavior problems

It is now well established that children of alcoholic parents are at increased risk for interpersonal and behavior problems, psychiatric disturbances, substance abuse (including early onset of alcohol use), and developmental trajectories of persistent alcohol problems (Chassin, Flora, & King, 2004; Jackson, Sher, & Wood, 2000; Jacob & Windle, 2000). Researchers have speculated that one pathway to later substance abuse disorders among children of alcoholics is through higher incidence of behavior problems or behavioral undercontrol, characterized by higher aggression, impulsivity, and sensation seeking (Sher, 1991). This model has been supported by empirical evidence indicating that children of alcoholic fathers have higher rates of externalizing behavior problems and behavioral undercontrol (e.g., Blackson, 1994; DeLucia, Belz, & Chassin, 2001; Edwards, Eiden, Colder, & Leonard, 2006; Jacob & Windle, 2000). However, with the exception of recent reports from the Michigan Longitudinal Study (e.g., Loukas, Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Krull, 2003), few studies have investigated the mediational pathways explaining the association between parental alcohol problems and children's externalizing behavior problems using longitudinal data. Two important mediators of this association that have been implicated in studies using other high-risk samples are children's self-regulatory abilities and lower parental warmth/sensitivity.

Self-Regulation

Self-regulation is defined as the process of modulating behavior and affect given contextual demands (Posner & Rothbart, 2000). Although regulatory processes begin to develop in the prenatal period, regulation evolves into a complex and relatively stable self-initiated process by the preschool period (see Calkins & Fox, 2002; Campbell, 2002). Recently, two related but distinct aspects of self-regulation in the preschool to early school age period have been delineated, effortful control and internalized conduct. Effortful control has been defined as the ability to suppress inappropriate behavior and perform required or appropriate behavior in response to environmental demands. Effortful control becomes increasingly important beyond the 2nd year of life, has considerable longitudinal stability, and predicts externalizing behavior problems at later ages (Eisenberg et al., 2005; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Kochanska, Murray, & Coy, 1997; Rothbart, Derryberry, & Posner, 1994). Internalization of rules of conduct has been defined as regulated or appropriate behavior in response to contextual demands even in the absence of surveillance (e.g., Kochanska & Aksan, 1995; Kopp, 1982; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). The normative change from external monitoring of child behavior to more self-regulated behavior even in the absence of close supervision results from children internalizing rules of conduct. The attainment of these self-regulatory skills in the preschool period sets the stage for successful adaptation during the transition to school and peer settings (Calkins & Fox, 2002).

Several developmental theories provide persuasive explanations for the link between self-regulation in the infant/toddler period and disruptive behavior in later childhood, highlighting the importance of parenting behavior as a salient predictor of self-regulation (Bradley, 2000; Calkins & Fox, 2002; Schore, 1994, 1996). Indeed, there is empirical evidence that the association between parenting and children's externalizing behavior problems is longitudinally mediated through the development of effective self-regulation (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). Few previous studies have examined this issue among children of alcoholics. One exception is the Michigan Longitudinal Study (Loukas, Fitzgerald, Zucker, & von Eye, 2001; Loukas et al., 2003). Results from this study indicate that children's behavioral undercontrol mediates the association between fathers' alcoholism and children's externalizing behavior trajectories. However, behavioral undercontrol in this study was measured using parent reports, as were externalizing problems. Thus, it is unclear if this association may be explained by shared-method variance. In the present study, we use multimethod assessments of both self-regulation and externalizing behavior problems to address this issue.

Parenting

Theoretical perspectives on the development of self-regulation have emphasized that the quality of parenting plays a key predictive role (Kopp, 1982). Empirical studies on this topic have also highlighted the role of maternal warmth, sensitivity, and disciplinary strategies as predictors of self-regulation (e.g., Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Eisenberg et al., 2001, 2003; Emde, Biringen, Clyman, & Oppenheim, 1991; Kochanska & Murray, 2000; Olson, Bates, & Bayles, 1990). Children with warm, sensitive parents are more likely to be able to regulate their arousal and focus attention on salient developmental demands. As a result, these children are more likely to be able to process parental directives, benefit from parental guidance, internalize parental rules, and inhibit inappropriate behavior.

Parenting behavior has also been hypothesized to be one pathway linking fathers' alcoholism to problems in self-regulation among children (e.g., Jacob & Leonard, 1994). This viewpoint suggests that parental alcoholism interferes with parents' abilities to remain consistently warm and supportive during parent–child interactions. Empirical studies linking fathers' alcoholism with parenting have observed that alcoholic fathers and mothers with alcoholic partners are less sensitive and have lower warmth or positive engagement with their infants and toddlers during play interactions compared with nonalcoholic fathers and mothers (Eiden, Chavez, & Leonard, 1999; Eiden, Leonard, Hoyle, & Chavez, 2004). Others have noted that fathers' alcoholism is associated with lower positive involvement and dyadic synchrony during parent–child interactions in the preschool years (e.g., Whipple, Fitzgerald, & Zucker, 1995) and lower positivity in adolescence (e.g., Jacob, Haber, Leonard, & Rushe, 2000). However, in spite of theoretical discussions on this topic, few studies have examined the predictive associations between parenting, self-regulation, and behavior problems among children of alcoholics during early childhood, and no existing studies have examined this process using longitudinal data.

Role of Antisocial Behavior and Depression

Parents' alcohol problems are generally nested within a high-risk environment characterized by other parental psychopathology (Fitzgerald, Davies, & Zucker, 2002). Two aspects of parental psychopathology most commonly associated with alcoholism are depression and antisocial behavior (Helzer, Burnam, & McEvoy, 1991; Zucker, Ellis, Bingham, & Fitzgerald, 1996). Thus, in addition to alcohol problems per se, concomitant parental depression and antisocial behavior are likely to influence child outcomes. Studies have noted that depression and antisocial behavior are associated with each other, and both depression and antisocial behavior may be predictive of poor parenting (Florsheim, Moore, Zollinger, MacDonald, & Sumida, 1999; Jameson, Gelfand, Kulcsar, & Teti, 1997; Martinez et al., 1996; Rosenblum, Mazet, & Benony, 1997). For instance, studies have demonstrated that depressed mothers have lower levels of involvement and are less verbally and emotionally responsive toward their infants (Jameson et al., 1997; Martinez et al., 1996; Rosenblum et al., 1997). Studies have also noted that children of mothers with co-occurring antisociality and depression are more likely to experience maternal hostility and physical maltreatment (Cohen, Caspi, Rutter, Tomas, & Moffitt, 2006) and that maternal hostility and negative affect mediate the association between maternal antisocial behavior and child conduct problems (Rhule, McMahon, & Spieker, 2004). These aspects of parental functioning may also be directly predictive of higher rates of externalizing behavior in children due to potential genetic linkages between parent and child negative affect (Conger, Neppl, Kim, & Scaramella, 2003; Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, & Taylor, 2003; Kane & Garber, 2004; Low & Stocker, 2005). The direct association between parents' depression and higher rates of child externalizing behavior problems has also been attributed to higher levels of stress and negative affect in the families with depressed parents (e.g., Low & Stocker, 2005). Finally, results from a few recent studies highlight the higher risk for externalizing behavior problems among families with comorbid antisocial and depressed parents (see Cohen et al., 2006).

Conceptual Model

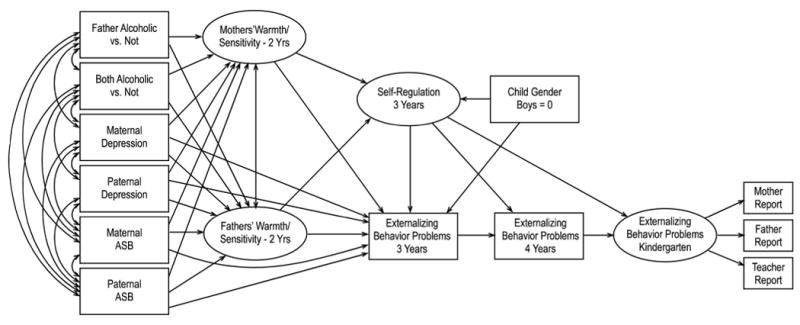

The major purpose of the present study was to test a conceptual model predicting children's externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten. This model is displayed in Figure 1 and incorporates the following hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that parents' alcohol diagnoses over the 12–18 month period would be associated with higher parental depression and antisocial behavior. Alcohol diagnoses, higher symptoms of depression, and higher antisocial behavior would be longitudinally predictive of poor parenting behavior, characterized by lower warmth/sensitivity at 2 years of child age. Lower parental warmth/sensitivity would be predictive of lower self-regulation in the preschool period (3 years of child age). Finally, lower self-regulation in the preschool period would be longitudinally predictive of higher externalizing behavior problems at kindergarten age, after controlling for prior levels of externalizing behavior problems. The model also includes child gender as a covariate, because boys have lower self-regulation (Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000) and higher externalizing behavior problems compared with girls (for a review, see Ehrensaft, 2005).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model predicting children's externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten.

This study is unique in its longitudinal design beginning in infancy, as most studies of alcoholic families begin in early adolescence, with the exception of the Michigan Longitudinal study, beginning at 3–5 years of age. The study is also unique in its inclusion of multiple indicators of children's behavior, its heavy emphasis on observational paradigms for many constructs, and the inclusion of parenting behavior as a key etiological construct. Although theoretical models of the development of externalizing behavior problems among alcoholic families have been the subject of much debate, few studies have used such a design to examine developmental processes that may account for this association.

Finally, predictors of externalizing behavior problems among children of alcoholics may be particularly critical to examine during transition to school settings. Children's ability to negotiate the transition to school and display appropriate behaviors in the school setting during kindergarten is likely to be predictive of their success in school at later ages. Indeed, theoretical reviews of the literature have noted that the development of self-regulatory skills in the preschool period is especially critical for a successful transition to the school setting (e.g., Calkins & Fox, 2002), and there is longitudinal stability in externalizing behavior problems from kindergarten to adolescence (Nagin & Tremblay, 1999). Increased knowledge of the developmental process leading to externalizing behavior problems among children of alcoholics is likely to be useful in the design of early interventions targeted at reducing the incidence of these problems. Targeting these interventions before school age may be particularly fruitful in increasing the potential of successful transition to the school setting among these high-risk children.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 227 families with 12-month-old infants at recruitment (111 girls and 116 boys). Families were classified as being in one of two major groups: the group consisting of parents with no or few current alcohol problems (or the NA group; n = 97) and the group consisting of families with one parent with alcohol problems (or the FA group; n = 130). Within the FA group, 96 families had one parent (in 94% of families, this was the father) who met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence or drank heavily (consumed more than 14 alcoholic beverages a week or more than 5 drinks on a single occasion), while the other parent drank lightly or abstained.1 In the remaining 34 families, fathers met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence and mothers either met similar criteria or drank heavily but did not acknowledge any alcohol problems (BA group). These classifications were based on parental responses at two time points: 12 and 18 months of child age. Thus, parents who met diagnostic criteria at either of the two time points were classified as being in the BA group. Families were assessed when the children were 12, 18, 24, 36, and 48 months of age and during kindergarten.

The majority of the parents in the study were Caucasian (94% of mothers and 87% of fathers), with a smaller percentage of African Americans (5% of mothers and 7% of fathers). Although parental education ranged from less than high school degree to master's degree, about half the mothers (57%) and fathers (55%) had received some education beyond high school or had a college degree. Annual family income ranged from $4,000 to $95,000 (M = $41,824, SD = $19,423). At the first assessment, mothers were residing with the biological father of the infant in the study. Most of the parents were married to each other (88%). At recruitment, mothers' age ranged from 19 to 40 years (M = 30.40, SD = 4.58). Fathers' age ranged from 21 to 58 years (M = 32.90, SD = 6.06). About 61% of the mothers and 91% of the fathers were working outside the home at the initial assessment. About 68% of the families had 1–2 children, including the target child. Thus, the majority of the families were middle-income, Caucasian families with 1–2 children in the household at recruitment.

Procedure

The names and addresses of these families were obtained from the New York State birth records for Erie County. These birth records were preselected to exclude families with premature (gestational age of 35 weeks or less) or low-birth-weight infants (birth weight of less than 2,500 g); maternal age of less than 18 years or greater than 40 years at the time of the infant's birth; plural births (e.g., twins); and infants with congenital anomalies, palsies, or drug withdrawal symptoms. Introductory letters were sent to a large number of families (n = 9,457) who met the above-mentioned basic eligibility criteria when their child was approximately 11 months of age. Each letter included a form that all families were asked to complete and return (response rate = 25%). Of these, about 2,285 replies (96%) indicated an interest in the study. Only a handful of the replies (n = 97 [4%]) indicated lack of interest. Respondents were compared with the overall population with respect to information collected on the birth records. These analyses indicated a slight tendency for infants of responders to have higher Apgar scores, higher birth weight, and a higher number of prenatal visits. Means for nonresponders versus responders were 8.94 and 8.97 for Apgar scores, 3,460 and 3,516 g for birth weight, and 10.31 and 10.50 for number of prenatal visits, respectively. Responders also were more likely to be Caucasian (88% of total births vs. 91% of responders), have higher educational levels, and have a female infant. These differences were significant given the large sample size, even though the size of the differences was minimal (effect size: Cohen's d < .22 in all analyses).

Parents who indicated an interest in the study were screened by telephone with regard to sociodemographic characteristics and additional eligibility criteria. Initial inclusion criteria included the following: parents were primary caregivers and cohabiting since the infant's birth; the infant was the youngest child, did not have any major medical problems, and had not been separated from the mother for more than a week; and the mother was not pregnant at the time of recruitment. Additional inclusion criteria were used to minimize the possibility that any observed infant behaviors could be the result of prenatal exposure to drugs or heavy alcohol use: Mothers could not have used drugs during pregnancy or past year (except for fewer than two instances of marijuana use), mothers' average drinking had to be less than 1 drink a day during pregnancy, and mothers could not drink 5 or more drinks on a single occasion during pregnancy. During the phone screen, mothers were administered the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria for alcoholism with regard to their partners' drinking (Andreasen, Rice, Endicott, Reich, & Coryell, 1986), and fathers were screened with regard to their alcohol use, problems, and treatment.

Women who reported drinking moderate to heavy amounts of alcohol during pregnancy (see criteria above) were excluded from the study to control for potential fetal alcohol effects. Because we had a large pool of families potentially eligible for the nonalcoholic group, alcoholic and nonalcoholic families were matched on race/ethnicity, maternal education, child gender, parity, and marital status.

Families visited the Research Institute on Addictions at five different child ages (12, 18, 24, and 36 months and upon entry into kindergarten), with three visits at each age. A parent questionnaire assessment was also conducted at 48 months. Informed written consents were obtained from both parents, and extensive observational assessments with both parents were conducted at each age. This article focuses on the 12-, 18-, 24-, 36-, 48-month, and kindergarten questionnaires, interviews, and observational assessments. At each assessment age (with the exception of 48 months), mother–child observations were conducted at the first visit, followed by a developmental assessment at the second visit. Father–child observations were conducted at the third visit. All observations were videotaped for later coding. There was a 4–6-week lag between the mother–child and father–child visits at each age. At the kindergarten assessment, teachers were contacted in the spring of the kindergarten year for completion of teacher reports.

Measures

Parental alcohol use

Once families were recruited into the study, a quantity–frequency measure of alcohol use adapted from Cahalan, Cisin, and Crossley (1969) was used to obtain a measure of average daily ethanol intake (AA/day) for both parents at 12 and 18 months. The measures at 12 and 18 months were averaged to obtain a composite index of AA/day for each parent. Frequency of binge drinking (drinking five or more drinks on the single occasion) was also measured at 12 and 18 months and averaged for a composite index of frequency of binge drinking. Finally, the University of Michigan version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM-CIDI; Anthony, Warner, & Kessler, 1994; Kessler et al., 1994) was used to assess alcohol abuse and dependence at 12 and 18 months. Several questions of the instrument were reworded to inquire as to “how many times” a problem had been experienced as opposed to whether it happened “very often.” Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses for current alcohol problems (in the past year at 12 months and past 6 months at the 18-month assessment) were used to assign final diagnostic group status. For abuse criteria, recurrent alcohol problems were described as those occurring at least 3–5 times in the past year or 1–2 times in three or more problem areas. Parents who met diagnostic criteria at either time point were assigned to the FA group. The UM-CIDI is a widely used diagnostic interview designed to assess substance abuse and dependence with high interrater reliability, high test–retest reliability, and good validity with regard to concordance with clinical diagnoses (see Kessler, 1995).

Parents' depression

Parents' depression was assessed at 12 and 18 months with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Inventory (CESD; Radloff, 1977), a scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in community populations. The CESD is a screening instrument with 20 symptoms of depression. Participants are asked to record the frequency of these symptoms over the past week using a scale ranging from 0 to 3. The total score may range from 0 to 60. The CESD is a widely used measure with high internal consistency (Radloff, 1977) and strong test–retest reliability (Boyd, Weissman, Thompson, & Myers, 1982; Ensel, 1982). Scores of 16 or higher on the CESD are considered to be in the clinically significant range (e.g., Ritchey, LaGory, Fitzpatrick, & Mullis, 1990). Only 12% of mothers and 10% of fathers had scores at or above 16 in this sample. To create an index of maternal and paternal depression over the 2nd year of the child's life, we averaged the CESD scores at each age and created a composite index of depression for each parent. The internal consistency of the scale ranged from .88 for fathers to .91 for mothers in this sample. The depression scores for both mothers and fathers were quite skewed and were transformed using square-root transformations.

Parents' antisocial behavior

A modified version of the Antisocial Behavior Checklist (ASB; Ham, Zucker, & Fitzgerald, 1993; Zucker & Noll, 1980) was used in this study at 12 months of child age. The measure was not readministered at 18 months because it is a measure of lifetime antisocial behavior, and we did not anticipate change over a 6-month period. Parents were asked to rate their frequency of participation in a variety of aggressive and antisocial activities across their lifetime along a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). The measure has been found to discriminate among groups with major histories of antisocial behavior (e.g., prison inmates, individuals with minor offenses in district court, university students; Zucker & Noll, 1980) and between alcoholic and nonalcoholic adult males (Fitzgerald, Jones, Maguin, Zucker, & Noll, 1991). Parents' scores on this measure were also associated with maternal reports of child behavior problems among preschool children of alcoholics (Jansen, Fitzgerald, Ham, & Zucker, 1995). The original measure has adequate test–retest reliability (.91 over 4 weeks) and internal consistency (coefficient α = .93). Because of concerns about causing family conflict as a result of parents reading each other's responses, items related to sexual antisociality and those with low population base rates (R. A. Zucker, personal communication, August 5, 1995) were dropped. This resulted in a 28-item measure of antisocial behavior. The internal consistency of the 28-item measure in the current sample was quite high for both parents (α = .90 for fathers and .82 for mothers). The antisocial behavior scores for both mothers and fathers were quite skewed and were transformed using square-root transformations.

Parenting quality

Mothers and fathers were asked to interact with their children as they normally would at home for 10 min in a room filled with toys at 24 months of child age. Mother–child and father–child interactions were conducted separately about 4–6 weeks apart. These interactions were coded using a collection of global 5-point rating scales developed by Clark, Musick, Scott, and Klehr (1980), with higher scores indicating more positive behavior. These scales have been found to be applicable for children ranging in age from 2 months to 5 years (Clark, 1999; Clark et al., 1980). Composite measures of maternal and paternal sensitivity, negative affect, and warmth were derived from these scales, yielding three composite scales for mothers and three for fathers. The sensitivity composite included items such as responsiveness, reading child cues, flexibility, low intrusiveness, and consistency/predictability. The negative affect composite included items such as angry/hostile tone of voice or mood, expressed negative affect, disapproval, and criticism. The composite of warmth included items such as expressed positive affect, animated mood, enjoyment or pleasure, social initiative, and positive involvement. Higher scores on these scales indicated high sensitivity, low negative affect, and high warmth.

Two sets of coders rated the play interactions. Coders who rated mother–child interactions did not rate the father–child interactions. All coders were trained on the Clark scales by Rina D. Eiden and were unaware of group membership and all other data. Interrater reliability was calculated for 17% of the sample (n = 38) and was high for all six subscales, with intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from .81 to .92.

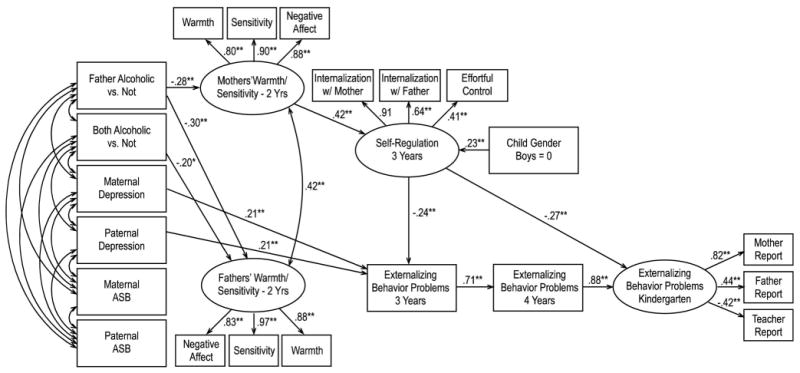

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses on the six composite scales to examine the fit of two measurement models, one for each parent. The three composite scales for each parent were used as measured indicators of the latent construct reflecting parental warmth/sensitivity. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the three parenting behavior scales for fathers loaded on one factor reflecting father's warmth/sensitivity (high warmth, low negative affect, and high sensitive responding, with factor loadings ranging from .83 to .97). Similarly, the three parenting behavior scales for mothers loaded on one factor reflecting mothers' warmth/sensitivity (with factor loadings ranging from .80 to .90).

Self-regulation

The latent construct of self-regulation used in data analyses included three measured indicators: an effortful control battery, an observational measure of internalization of maternal rules, and an observational measure of internalization of fathers' rules. The effortful control battery consisted of a battery of tasks developed by Kochanska, Padavich, and Koenig (1996) and Kochanska and Knaack (2003). The effortful control battery used at the 3-year visit consisted of three tasks: a snack delay, a whisper, and a lab gift. In snack delay, the child has to wait for the experimenter to ring a bell before retrieving an M&M from under a glass cup (four trials: delays of 10, 20, 30, and 15 s). Halfway through the delay, the experimenter lifts the bell but does not ring it. Coding ranges from 0 (eats the snack before bell is lifted) to 4 (waits for bell to ring before touching cup or snack). The mean score on all four trials was used as the effortful control score on this task. In the whisper task, the child is asked to whisper the names of 10 consecutively presented cartoon characters, some familiar and some unfamiliar, with codes ranging from 0 (shout) to 3 (whisper). Children have more difficulty modulating their voices to a whisper for familiar characters compared with unfamiliar ones, thus requiring higher levels of effortful control for voice modulation when they are presented with the familiar characters. During the lab gift delay task, the child is asked to sit on a chair facing away from the table where the experimenter is noisily wrapping a gift for the child. The child is asked not to peek. After wrapping the gift, the experimenter leaves the room for 2 min, asking the child not to touch the gift until he or she returns. Coding involves a peeking score (on a 3-point scale), a latency to peek score, and latency to touch score. As in previous studies of effortful control among young children (e.g., Kochanska et al., 1997, 2000), we created a composite score for effortful control. The scores on all three tasks were standardized, and a final effortful control score was computed by taking the average of all the scores. The internal consistency (α) of this scale at 3 years was .79.

Observations of child internalization were conducted according to the paradigm developed by Kochanska and her colleagues (Kochanska & Aksan, 1995; Kochanska et al., 1996). The paradigm was identical for mothers and fathers. Parents were instructed to show the child a shelf with attractive objects when they entered the observation room and to instruct the child to not touch those objects. Parents were told that they could repeat this prohibition and/or take whatever actions they would normally take to keep their toddler from touching these prohibited objects during the hour-long session that followed (consisting of free play, structured play, clean-up, reading, etc.). About an hour into the observation session in the room with the prohibited objects, the experimenter asked the parent to move to the front of the room. A screen dividing the room in half was partially closed so that the parent and the child were unable to see each other. The child was asked to stay on the side of the divider containing the prohibited objects and sort plastic cutlery while the experimenter interviewed the parent on the other side of the room.

Children's internalization of the parental directive to not touch the objects on the prohibited shelf was assessed during a 12-min observational paradigm (Kochanska & Aksan, 1995). During the first 3 min of the internalization paradigm, the child was left alone with the cutlery task. At the end of this time, a female research assistant unfamiliar to the child came in and played with the prohibited objects with obvious enjoyment for 1 min and then left the room. Prior to leaving, she wound up the music box, started the music, and replaced it on the shelf. The child was left with the cutlery sorting for the next 8 min. The child's behavior was coded for every 15-s interval according to the coding criteria developed by Kochanska and Aksan (1995). These codes consisted of various levels of child behavior: sorting cutlery (scored 5); looking at prohibited objects with no attempt to touch (scored 4); self-correction before touch, when a child reaches out to touch but then withdraws hands before the touch can be completed (scored 3); self-correction after touch, when there is a fleeting touch followed by withdrawal (scored 2); gentle touch, when a child touches very tentatively (scored 1); and deviation, when a child plays with prohibited objects in a “wholehearted,” unrestrained manner (scored 0). These rating scales were averaged across the entire 12 min so that high scores reflected high behavioral internalization and low scores reflected deviation or low internalization of parental rules.

Internalization was coded by two independent coders blind to group status and other information about the families. A sample of all three periods or contexts from 20 cases for 3-year internalization data was chosen to calculate interrater reliability (640 15-s coded segments). Kappa was .98. The percentages of agreement for the categories ranged from 90% for gentle touch to 100% for deviation for both mothers and fathers.

Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on the three self-regulation measures: behavioral measure of effortful control, internalization of maternal rules, and internalization of fathers' rules. The three scales were used as measured indicators of the latent construct reflecting children's self-regulation at 3 years. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the three scales loaded on one factor reflecting high self-regulation, with factor loadings of .41, .91, and .64 for the behavioral composite for effortful control, internalization of maternal rules, and internalization of fathers' rules, respectively.

Externalizing behavior problems

Externalizing behavior problems were assessed at 3 and 4 years of age as well as in kindergarten. Maternal and paternal ratings were used at 3 and 4 years of age. Teacher ratings, maternal ratings, and paternal ratings of externalizing behavior problems were assessed in kindergarten. Maternal and paternal ratings of externalizing behavior problems were obtained using the externalizing behavior subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1992). The CBCL is a widely used measure of children's behavioral/emotional problems with well-established psychometric properties. It consists of items rated on a 3-point response scale ranging from not true to very true, with some open-ended items designed to elicit detailed information about a particular problem behavior. Higher scores indicate higher externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten.

Teacher ratings of externalizing behavior problems were measured using the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation Scales (LaFreniere & Dumas, 1996; LaFreniere, Dumas, Capuano, & Dubeau, 1992). The scale measures three overall dimensions of social competence, internalizing behavior problems, and externalizing behavior problems. Only the externalizing behavior problems scale was used in these analyses. This scale measures four dimensions of problem behaviors: anger, aggressive behavior, egotistical behavior, and oppositional behavior. Teachers were asked to rate the child in the study and four other classmates on a 6-point response scale ranging from never to always. This scale has been validated for children ranging in age from 3 to 6 years and has been used in a variety of settings and cultural contexts (Butovskaya & Deminaovitsch, 2002; Kotler & McMahon, 2002; LaFreniere et al., 2002). High scores on this scale indicate low externalizing behavior.

An average of maternal and paternal ratings was used to create a composite externalizing behavior scale at 3 and 4 years. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the three externalizing behavior scales: teacher report, maternal report, and paternal report at kindergarten. The three scales were used as measured indicators of the latent construct reflecting children's externalizing behavior problems. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the three scales loaded on one factor reflecting high externalizing behavior problems, with factor loadings of .82, .44, and −.42 for maternal report, paternal report, and teacher report, respectively.

Results

Missing Data and Data Analytic Approach

As would be expected of any longitudinal study involving multiple family members, there were incomplete data for some participants at one or more of the five assessment points included in this study. Of the 227 families included in analyses, all provided data at 12 and 18 months; 222 mothers and 218 fathers provided data at 24 months; 205 mothers and 193 fathers provided data at 36 months; and 185 mothers, 174 fathers, and 148 teachers provided data at kindergarten. Among the NA group families, 83% of families had maternal report data, 80% had paternal report data, and 67% had teacher report data in kindergarten. Among the FA group families, 80% had maternal report data, 73% had paternal report data, and 64% had teacher report data in kindergarten. There were no group differences between families with missing versus complete data on any of the alcohol variables, depression, or parenting. There were also no differences between the two groups of families (complete vs. missing data) on any of the child outcome variables. However, families with missing data had mothers who reported higher antisocial behavior compared with those with complete data (Ms = 39.25 and 41.96, SDs = 8.54 and 10.01, respectively).

Although it is clear that the data were not missing completely at random at kindergarten because of group differences on maternal antisocial behavior, data did meet criteria for being missing at random (MAR). Little and Rubin (1989) defined data as MAR when cases with incomplete data differed from cases with complete data, but the pattern of missingness could be predicted from other variables in the database. They specifically cited longitudinal data in which the potential cause of missingness (e.g., low self-esteem in a study about self-esteem) has been measured at earlier time points as meeting criteria for MAR. Discussions of missing data have also noted that the assumption of MAR can never be definitively assessed. However, given that no differences were found between families with missing data and those with complete data on parenting or child outcome variables, the assumption of MAR seems tenable for these data. To take advantage of all data provided by all participants, we used full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) to estimate parameters in our models (Arbuckle, 1996). This missing data approach includes all cases in the analysis, even those with missing data. When data are MAR, FIML produces good estimates of population parameters. Even if the data are not MAR, FIML is thought to produce more accurate estimates of population parameters than would be obtained if listwise deletion were used.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1. All SEM analyses were conducted using Mplus (Version 4.0; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2006). FIML estimation procedures were used and standardized parameter estimates are presented. The goodness of fit of the models was examined by using the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). The CFI varies between 0 and 1, and values of .90 or higher indicate acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1995). The RMSEA is bounded by 0 and will take on that value when a model exactly reproduces a set of observed data. A value of .05–.06 is indicative of close fit, a value of .08 is indicative of marginal fit, and higher values are indicative of poor fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1994). Because parental depression and antisocial behavior variables remained skewed, even after square root transformation, the Satorra–Bentler chi-square was also computed and reported for the model (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). Finally, the indirect effect for the hypothesized association between parents' alcohol diagnoses and children's externalizing behavior problems was computed using the model indirect command in Mplus. The indirect effect is calculated using the delta method (Sobel, 1982).

Demographic and Descriptive Information

We first examined demographic and descriptive information regarding the families in the two groups. Approximately 11% of families were not living together by the kindergarten assessment. Of these, 13% were in the FA group and 8% were in the NA group. Chi-square analyses indicated that this difference was not significant, χ2(1, N = 173) = 1.32, p > .05. Only 2% of the children who completed assessments at kindergarten had no contact with their biological father. The remaining children had regular contact with their fathers (at least once a week) for at least 15 hours per week. Overall, 20 fathers (9%) had been in substance abuse treatment at some point since recruitment and the kindergarten assessment, and 18 (8%) had been in treatment for psychological problems. By kindergarten, 14 (6%) mothers had been in substance abuse treatment, and 27 (12%) had been in treatment for psychological problems.

Descriptive information regarding group differences on parent risk variables and parents' education are presented in Table 1. As indicated in the table, fathers in the FA group (including the group with alcoholic/heavy drinking mothers) consumed more alcohol and had higher numbers of alcohol symptoms compared with those in the NA group. Fathers in the FA group were also more antisocial and displayed lower warmth and sensitivity during interactions with their toddlers. Alcoholic fathers with nonalcoholic partners reported more symptoms of depression and displayed higher negative affect with their toddlers compared with those in the NA group. Fathers in the FA group also had lower levels of education compared with those in the NA group. Mothers in the both alcoholic group engaged in heavier drinking and had more alcohol symptoms compared with those in the other two groups, as would be expected. These mothers also were the most antisocial, followed by nonalcoholic mothers with alcoholic partners, with mothers in the NA group having the lowest level of antisocial behavior. Finally, nonalcoholic mothers with alcoholic partners displayed lower warmth and sensitivity and higher negative affect compared with those in the NA group.2

Table 1. Descriptive Information and Effect Size by Group Status.

| FA group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Father alcoholic (n = 96) |

Both alcoholic (n = 34) |

NA group (n = 97) | Partial η2 | |||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Father | |||||||||

| QFI | 0.84 | 0.99 | 1.24a | 1.03 | 1.53a | 1.07 | 0.22b | 0.38 | .49 |

| Binge | 1.88 | 1.90 | 2.76a | 1.62 | 3.79c | 1.79 | 0.40b | 0.69 | .62 |

| No. of symptoms | 5.88 | 13.48 | 9.30a | 16.17 | 13.25a | 17.90 | 0.12b | 0.36 | .42 |

| Depression | 7.15 | 6.35 | 8.42a | 6.83 | 7.28 | 5.90 | 5.92b | 5.85 | .05 |

| ASB | 39.86 | 8.94 | 42.08a | 8.41 | 45.12a | 11.63 | 35.96b | 6.42 | .18 |

| Warmth | 4.10 | 0.86 | 3.83a | 0.88 | 3.76a | 0.94 | 4.46b | 0.67 | .14 |

| Sensitivity | 4.46 | 0.68 | 4.27a | 0.67 | 4.27a | 0.73 | 4.70b | 0.59 | .10 |

| Neg. affect | 4.65 | 0.53 | 4.51a | 0.61 | 4.64 | 0.32 | 4.78b | 0.48 | .06 |

| Education | 13.72 | 2.43 | 13.41a | 2.39 | 12.97a | 1.93 | 14.27b | 2.52 | .04 |

| Mother | |||||||||

| QFI | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.09a | 0.10 | 0.48b | 0.36 | 0.07a | 0.10 | .40 |

| Binge | 0.47 | 0.79 | 0.35a | 0.51 | 1.65c | 1.16 | 0.17b | 0.36 | .37 |

| No. of symptoms | 0.56 | 1.50 | 0.25a | 0.54 | 2.68b | 2.82 | 0.10a | 0.48 | .48 |

| Depression | 7.83 | 6.70 | 8.72 | 7.53 | 9.47 | 6.80 | 6.43 | 5.54 | .03 |

| ASB | 35.85 | 5.40 | 42.08a | 8.41 | 45.12c | 11.63 | 35.96b | 6.42 | .11 |

| Warmth | 4.28 | 0.73 | 4.03a | 0.83 | 4.20 | 0.59 | 4.54b | 0.58 | .11 |

| Sensitivity | 4.61 | 0.39 | 4.47a | 0.60 | 4.64 | 0.39 | 4.72b | 0.45 | .05 |

| Neg. affect | 4.74 | 0.43 | 4.65a | 0.53 | 4.75 | 0.29 | 4.82b | 0.36 | .04 |

| Education | 13.49 | 1.82 | 13.58 | 1.95 | 13.09 | 1.60 | 13.55 | 1.76 | .01 |

Note. Means with different subscripts are significantly different from each other. There was a significant group difference on maternal depression between the FA (one parent with alcohol problems) and NA (parents with no or few current alcohol problems) groups. QFI = quantity/frequency index; Binge = frequency of binge drinking; ASB = antisocial behavior.

Correlational Analyses

At the level of correlations, fathers' alcohol diagnosis (FA vs. not) was associated with higher child externalizing behavior at 4 years (see Table 2). Higher maternal depression was associated with lower paternal warmth/sensitivity, higher negative affect, and higher child externalizing behavior problems at 3 and 4 years and with parent reports at kindergarten. Higher paternal depression was associated with lower paternal warmth and higher externalizing behavior problems at 3 and 4 years and at kindergarten. Higher maternal ASB was associated with lower paternal and maternal warmth and sensitivity, lower paternal negative affect, and higher child externalizing behavior problems at 3 years, 4 years, and kindergarten according to parental reports. Higher paternal ASB was associated with lower maternal and paternal warmth, lower paternal sensitivity, lower child internalization of fathers' rules at 3 years, and higher externalizing behavior problems at 3 years, 4 years, and kindergarten according to parent report.

Table 2. Correlations Among Study Variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FA vs. not | — | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. BA vs. not | −.35 | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. M depression | .10 | .11 | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. F depression | .20 | .02 | .27 | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 5. M ASB | .08 | .28 | .34 | .22 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. F ASB | .23 | .25 | .31 | .31 | .44 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 7. M warmth | −.28 | −.06 | −.07 | −.03 | −.16 | −.15 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 8. M sensitivity | −.22 | .03 | −.05 | .05 | −.15 | −.07 | .72 | — | |||||||||||||

| 9. M neg. affect | −.18 | .00 | −.07 | .04 | −.11 | −.03 | .70 | .80 | — | ||||||||||||

| 10. F warmth | −.26 | −.17 | −.22 | −.14 | −.27 | −.23 | .44 | .39 | .37 | — | |||||||||||

| 11. F sensitivity | −.24 | −.12 | −.19 | −.11 | −.24 | −.18 | .41 | .47 | .42 | .85 | — | ||||||||||

| 12. F neg. affect | −.22 | −.01 | −.21 | −.09 | −.19 | −.13 | .31 | .36 | .37 | .74 | .81 | — | |||||||||

| 13. Int.: M | −.04 | .01 | .01 | .10 | .03 | .09 | .21 | .30 | .28 | .05 | .12 | .04 | — | ||||||||

| 14. Int.: F | −.03 | .04 | −.07 | −.09 | .00 | −.15 | .12 | .22 | .17 | .09 | .15 | .04 | .55 | — | |||||||

| 15. EC | −.03 | .04 | −.04 | −.04 | −.10 | .02 | .25 | .23 | .27 | .15 | .17 | .10 | .35 | .23 | — | ||||||

| 16. CBCL-3 yrs. | .13 | .05 | .30 | .30 | .18 | .25 | −.13 | .00 | −.04 | −.08 | −.01 | −.03 | −.16 | −.14 | −.21 | — | |||||

| 17. CBCL-4 yrs. | .14 | .08 | −.32 | .25 | .25 | .25 | −.15 | −.03 | −.07 | −.19 | −.12 | −.15 | −.08 | −.07 | −.11 | .68 | — | ||||

| 18. MR: CBCL | .12 | .07 | .22 | .16 | .25 | .17 | −.21 | −.16 | −.19 | −.22 | −.19 | −.23 | −.25 | −.13 | −.18 | .56 | .64 | — | |||

| 19. FR: CBCL | .05 | .00 | .17 | .35 | .15 | .24 | .03 | .08 | .07 | −.05 | .03 | −.01 | −.09 | −.17 | −.10 | .48 | .53 | .38 | — | ||

| 20. TR: Ext. | −.07 | .02 | −.06 | −.28 | −.05 | −.05 | .09 | .13 | .10 | .02 | .04 | .13 | .30 | .27 | .16 | −.11 | −.15 | −.32 | −.18 | — | |

| 21. Child gender | .01 | −.04 | −.06 | −.04 | −.04 | −.01 | .04 | .09 | .10 | .19 | .23 | .20 | .18 | .21 | .14 | −.09 | −.06 | −.16 | −.06 | .14 | — |

Note. High scores on maternal and paternal negative affect indicate low negative affect. High scores on teacher ratings for externalizing behavior indicate low externalizing behavior. The control group = 0 for dummy codes of father alcoholic versus not and mother alcoholic versus not. These are based on 12- and 18-month diagnostic information. Maternal and paternal warmth, sensitivity, and negative affect were coded during mother-toddler interactions at 2 years of child age. Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant correlations (p < .05). FA = one parent with alcohol problems; BA = both parents with alcohol problems; M = mother; F = father; ASB = antisocial behavior; Int. = internalization of rules; EC = effortful control; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist—externalizing behavior subscale; MR = maternal report; FR = fathers' report; TR = teachers' reports.

There were consistent associations between child self-regulation indices at 3 years and externalizing behavior problems at 3 years, 4 years, and kindergarten. Higher effortful control at 3 years was associated with lower externalizing behavior problems at 3 years and at kindergarten according to maternal and teacher reports. Higher internalization of maternal rules was associated with lower externalizing behavior problems at 3 years and at kindergarten according to paternal and teacher reports. Higher internalization of fathers' rules was associated with lower externalizing behavior problems at 3 years and at kindergarten according to maternal and teacher reports. Finally, indices of child self-regulation and externalizing behavior problems were correlated with each other.

Testing the Conceptual Model

The conceptual model tested included dummy-coded variables for group status (father alcoholic vs. not, both alcoholic vs. not), maternal and paternal warmth/sensitivity during parent–toddler interactions at 2 years, children's self-regulation at 3 years, and children's externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten, and it measured indicators for parents' alcohol diagnosis (dummy coded so that the NA group = 0), depression, and antisocial behavior (see Figure 1). The model included covariances between exogenous predictors (alcohol diagnosis, depression, and antisocial behavior); paths from predictors to paternal and maternal warmth/sensitivity; paths from parental sensitivity latent constructs at 2 years to the latent construct for self-regulation at 3 years; paths from child self-regulation at 3 years to externalizing behavior problems at 3 years, 4 years, and kindergarten; and covariance between the residuals of the latent variables for maternal and paternal warmth/sensitivity. Finally, child gender was included in the model, with paths to children's self-regulation and externalizing behavior problems at 3 years, given prior evidence regarding gender differences on these constructs.

Results indicated that this conceptual model fit the data adequately, Satorra–Bentler χ2(149) = 207.31, p = .001, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .04. The model is depicted in Figure 2. This model indicated that the within-time covariance between the residuals of the latent constructs for maternal and paternal warmth/sensitivity was significant and positive, indicating that higher maternal warmth/sensitivity was moderately associated with higher paternal warmth/sensitivity at 2 years of child age. In addition, the parental risk factors (alcohol, depression, and antisocial behavior) were generally associated with each other. Fathers in the FA group reported higher depression and antisocial behavior, parents in the BA group were more antisocial (both mothers and fathers), maternal depression was associated with higher paternal depression and higher maternal and paternal antisocial behavior, and maternal and paternal antisocial behavior were positively associated with each other.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal associations between parenting, self-regulation, and externalizing behavior problems: structural equation modeling. The numbers represent standardized path coefficients. Nonsignificant paths are not depicted in the model for ease of presentation. Covariances between exogenous variables were included in the model but not depicted in the figure. The error terms for the measured indicators are not depicted in the figure. High scores on negative affect and teacher reports indicate low negative affect and low externalizing behavior problems. ASB = antisocial behavior. *p < .05. **p < .01.

The structural paths indicated that after controlling for parents' depression and antisocial behavior, fathers' alcohol diagnosis at 12 and 18 months was predictive of lower maternal warmth/sensitivity at 2 years, and parents' alcohol diagnosis was predictive of lower paternal warmth/sensitivity at 2 years. Lower maternal warmth/sensitivity at 2 years was predictive of lower self-regulation at 3 years. Lower self-regulation at 3 years was concurrently associated with higher externalizing behavior problems at 3 years and longitudinally predictive of higher externalizing behavior problems at kindergarten after controlling for externalizing behavior problems at 3 and 4 years. Maternal and paternal depressions were directly and uniquely predictive of externalizing behavior problems at 3 years. Child gender was associated with children's self-regulation at 3 years such that girls had higher self-regulation compared with boys. The indirect effect of fathers' alcohol diagnosis → maternal warmth/sensitivity at 2 years → child self-regulation at 3 years → externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten was significant (z = 2.25, p < .05).

Discussion

The results provide support for the hypothesis that one pathway linking fathers' alcoholism to children's externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten is via lower levels of maternal warmth/sensitivity leading to poor self-regulation skills in the preschool years, which in turn predicts higher externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten. A number of studies have reported the significance of parenting behavior for the development of self-regulation (Brody, Murry, Kim, & Brown, 2002; Crockenberg & Littman, 1990; Kochanska & Aksan, 1995; Kopp, 1982). For instance, studies have reported that mutual positive affect during mother–child interactions during compliance procedures and parents' gentle guidance were both concurrently and longitudinally predictive of children's internalization of rules (e.g., Kochanska & Aksan, 1995). The important role of parenting in predicting risk trajectories for outcomes that may be conceptually related to lower self-regulation, such as drinking and drug use, has also been reported in previous longitudinal studies of children of alcoholics (e.g., King & Chassin, 2004). Further, parenting behavior has been hypothesized to be one pathway linking fathers' alcoholism to problems in self-regulation among children of alcoholics (e.g., Jacob & Leonard, 1994). Although this hypothesis has been the topic of theoretical discussions (see Zucker, Kincaid, Fitzgerald, & Bingham, 1995), it has seldom been examined empirically in early childhood for alcoholic samples. The current results provide empirical support for this hypothesis with regard to one major goal of socialization, the development of self-regulation.

Although the fathers' alcoholism was predictive of both maternal and paternal warmth/sensitivity at 2 years of child age, after controlling for the association between maternal and paternal parenting, only maternal parenting accounted for unique variance in self-regulation at 3 years. Previous reports have indicated that when maternal and paternal behavior are tested in two separate models, fathers' warmth or sensitivity mediates the association between fathers' alcohol problems and self-regulation over the 2–3-year period (Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2004, 2006). Indeed, at the level of correlations, higher fathers' warmth at 2 years was associated with higher child effortful control at 3 years, and higher sensitivity was associated with higher effortful control and internalization of fathers' rules. However, after controlling for the effects of mothers' warmth/sensitivity, fathers' warmth/sensitivity did not account for unique variance in children's self-regulation. These differences in results may be attributable to several factors. Maternal and paternal warmth/sensitivity were moderately associated with each other (see Figure 2), and the conceptual model tested in the current study controlled for the effects of the other parent. Latent constructs were used in model testing in the current study, whereas only the measured indicators of parents' warmth or sensitivity were tested in previous studies (e.g., Eiden et al., 2006; Eiden, Leonard, et al., 2004). Finally, unlike previous studies (e.g., Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2004), longitudinal data predicting self-regulation at 3 years from parenting at 2 years were used in the current study. We know of no other studies that have examined the unique variance accounted for by fathers' parenting behavior after controlling for maternal behavior in predicting children's self-regulation from the toddler to preschool period. This is an area for further exploration and replication.

Contrary to expectations, there were no unique associations between parents' depression or antisocial behavior and parental warmth/sensitivity, although there were some consistent associations between depression or antisocial behavior and parenting at the level of correlations. However, once all of the parental psychopathology variables, including alcoholism, diagnoses were included in the model, only alcohol diagnosis was a unique predictor of parenting. One explanation for this may be the nature of the sample. Although parents in the alcoholic group had higher levels of depression and antisocial behavior compared with those in the nonalcoholic group, in this community sample of alcoholic and nonalcoholic parents, levels of paternal depression and antisocial behavior were relatively low. For instance, only 12% of mothers and 10% of fathers had CESD scores at or above 16. Previous studies recruiting participants for higher levels of depression have reported fairly strong and consistent associations between parental depression and parenting behavior (e.g., Jameson et al., 1997). Moreover, unlike the authors of other longitudinal studies of alcoholic fathers, we did not preselect fathers with high levels of antisocial behavior (e.g., DWI offenders). Thus, the majority of our families, even those who met diagnoses for alcoholism, were relatively high functioning with regard to other symptoms. Given this background, the associations between parental risk variables and parenting and child outcomes reported in this study are conservative.

There has been strong empirical support in recent years of the hypothesis that children's self-regulation mediates the association between parenting and externalizing behavior problems (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). Indeed, in at least one previous study, the longitudinal paths from parenting to self-regulation to externalizing behavior problems were supported even after controlling for the stability in these variables over time (Eisenberg et al., 2005). Most other studies have either focused on the association between parenting and self-regulation (e.g., Brody & Ge, 2001; Brody et al., 2002) or on the association between self-regulation and behavior problems, especially in early childhood (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001; Zahn-Waxler et al., 1996), and few have been longitudinal in design. The indirect association between fathers' alcoholism and children's externalizing behavior problems via parenting and self-regulation is particularly significant given recent results from two longitudinal studies of children of alcoholics indicating that child lack of control (a concept similar to self-regulation) mediated the relation between paternal alcoholism and subsequent externalizing behavior problems among boys (Loukas et al., 2001) and the relation between parental alcoholism and drug use disorders in young adulthood (King & Chassin, 2004). The results are supportive of the hypothesis that early self-regulatory difficulties mediate the association between parents' alcohol problems and children's externalizing behaviors, and they highlight the important role of parenting as an explanatory variable. Taken together with previous results from longitudinal cohorts of children of alcoholics (e.g., Hussong, Curran, & Chassin, 1998; King & Chassin, 2004; Loukas et al., 2001), the current results suggest that this trajectory toward increasing self-regulatory difficulties may begin early in life, and problems in self-regulation may be an early precursor to the developmental trajectory of behavior problems and potential substance use disorders in adolescence.

Contrary to expectations, heavy drinking or alcoholic mothers with alcoholic partners did not display lower warmth/sensitivity during play interactions with their toddlers compared with those in the NA group. Few studies have examined the role of maternal postnatal alcohol use in the absence of heavy prenatal exposure, with one exception (O'Connor, Sigman, & Kasari, 1992). The O'Connor et al. study was limited to older mothers who consumed moderate amounts of alcohol during pregnancy, and the role of fathers' alcohol use was not examined. Results indicated no association between maternal postnatal alcohol use and maternal behavior during mother–infant interactions. One explanation for the lack of findings specific to maternal alcohol use in the present study may be lack of power because of small group size. Another explanation may be that mothers in this group were more antisocial but were generally high functioning, were recruited from the community, were excluded if they had used alcohol during pregnancy, and had volunteered for a longitudinal study of parenting and child development. Thus, the present study may have had a restricted range of alcohol problems for mothers compared with other studies of alcoholic or heavy drinking mothers. Fathers in this group did display lower levels of warmth and sensitivity during play interactions. The range restriction for alcohol problems did not apply to fathers, and the present results may be reflective of this. Indeed, the association between fathers' alcohol diagnosis and fathers' warmth/sensitivity during play interactions seems fairly robust by 2 years of child age, regardless of maternal alcohol problems. These results are unique to this data set, for we know of no other longitudinal studies of alcoholic fathers beginning in the infant/toddler period.

Nonalcoholic mothers with alcoholic partners displayed lower warmth/sensitivity during mother–child interactions. A few previous studies have reported similar results at older ages. For instance, Jacob et al. (2000) reported that wives of antisocial alcoholics were less positive and less instrumental during naturalistic interactions involving all family members in the home. These results may reflect overall family stress due to fathers' drinking or greater disruptions in the marital relationship (Eiden, Leonard, et al., 2004).

As expected, boys had lower self-regulation compared with girls. This is supportive of previous studies indicating that preschool boys have lower effortful control compared with girls and have lower levels of internalized conduct compared with girls (e.g., Forman, Aksan, & Kochanska, 2004; Kochanska, Forman, Aksan, & Dunbar, 2005; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Zahn-Waxler, Usher, Suomi, & Cole, 2005). However, contrary to expectations, the path from child gender to externalizing behavior problems at 3 years was nonsignificant, although there were gender differences in children's externalizing behavior problems, as reported previously in this and other data sets (Edwards et al., 2006). One interpretation of these findings is that gender differences in externalizing behavior problems may be explained by gender differences in the development of self-regulation. Indeed, researchers have speculated that gender differences in the development of empathy, guilt, and internalization of distress leading to different levels of self-regulation may explain gender differences in behavior problems (e.g., Zahn-Waxler et al., 2005). Future studies with larger sample sizes may well examine whether associations between parental risk factors, parenting, self-regulations, and children's externalizing behavior problems vary by child gender.

Although the findings from our study fill an important gap in the literature, there are several significant limitations as well. First, we chose to focus almost exclusively on parental warmth/sensitivity as the potential intervening or mediating variable. Previous studies have discussed the importance of child temperament in predicting the development of self-regulation. Aspects of child temperament such as fearfulness and attentional abilities have important theoretical and empirically validated associations with aspects of self-regulation such as effortful control and internalization (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Kochanska, Murray, & Coy, 1997). We chose to primarily focus on parenting variables as mediators in light of previous findings that children of alcoholics do not display strong differences in temperament in infancy (including both parent ratings and observed behavior) but do have lower quality parent–child interactions in the infancy and toddler periods (Eiden et al., 1999; Eiden, Leonard, et al., 2004). A second limitation is that the response rate to our open letter of recruitment was slightly above 25%. This raises the possibility that respondents to our recruitment may not have been representative of families with 12-month-old infants. Our comparison of respondents with the entire population of birth records suggested that the differences were small with respect to the variables that we could examine. However, there could have been more significant differences in variables that we could not assess. Thus, although generating our sample from birth records has important advantages over newspaper or clinic-based samples, generalizability of results may be limited to the population of higher functioning families, who may be more likely to respond to open letters of recruitment about participation in research. A third limitation is that given the nature of the design, the role of maternal alcohol problems cannot be examined independent of fathers' alcohol problems. Not only was this sample restricted with regard to maternal alcohol consumption—because one exclusion criteria was maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy—but it was also limited because the number of mothers with postnatal alcohol problems was relatively small. However, it is important to note that in the majority of families with alcohol problems, maternal alcohol problems exist in the context of paternal alcohol problems. In other words, women with alcohol problems are more likely to have partners with alcohol problems than vice versa (Roberts & Leonard, 1997). Finally, in this conceptual model, we hypothesized that parents' warmth and sensitivity at 2 years would predict children's self-regulation at 3 years. It is possible that children who had higher self-regulation were more likely to elicit higher warmth and sensitivity from their parents, and vice versa. Future studies may well examine this possibility of bidirectional associations between parenting and children's self-regulation. Given the limitations of sample size, and the complexity of the model, we were unable to test separate models for boys versus girls or alcoholic versus nonalcoholic families. This is an important area of investigation for future studies with larger sample sizes. Finally, these results may not be generalizable to families of single mothers who separated from or never lived with an alcoholic partner. One eligibility requirement at the time of recruitment when the child was 12 months old was that biological parents had been living together since the child's birth. This was important so that we could examine the effects of fathers' alcoholism on family functioning, parenting, and child development. However, this also limits generalizability of our findings to families who were intact when the child was a year old.

The current study is unique within the children of alcoholics literature in its use of longitudinal design beginning in infancy, examination of developmental processes, use of multiple indicators for most constructs, use of observational paradigms, and attention to issues regarding method variance. The finding that observational and laboratory measures of children's self-regulation are longitudinally predictive of parent and teacher reports of children's externalizing behavior is not only important conceptually, it also represents a significant methodological advance in this area of research. Another strength of the study is the inclusion of both maternal and paternal parenting behavior as potential mediators of child outcomes instead of maintaining a focus exclusively on maternal behavior. The current study also extends previous research in this area by focusing on developmental processes that may explain higher rates of externalizing behavior problems among children of alcoholics. The results highlight the role of maternal warmth/sensitivity and the development of self-regulation as key mediating processes and the unique role of fathers' alcoholism even in the context of other symptoms of psychopathology. The current results also suggest that these processes begin early in children's lives. When considered in light of other longitudinal data indicating high degree of stability in externalizing behavior problems from kindergarten to adolescence (Broidy et al., 2003), the results emphasize that parenting interventions designed to improve parental warmth/sensitivity and children's self-regulation may be most beneficial in the toddler/preschool period.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant 1RO1 AA 10042-01A1 and National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant 1K21DA00231-01A1. We thank parents and children who participated in the study and the research staff who were responsible for conducting and coding numerous assessments with these families. Special thanks go to Jay Belsky for help with the initial composites for parent–interaction scales and to Grazyna Kochanska for the self-regulation assessments.

Footnotes

Data were analyzed with and without the six mothers in the FA group who drank heavily. The parameter estimates remained unchanged. Thus, final results are presented with the complete sample.

A number of exogenous variables were considered in model testing but not included in the final model. These were fathers' education, treatment for alcohol problems or psychological problems for either parent by the kindergarten assessment (dummy-coded variable of treatment vs. no treatment), a dummy-coded variable for biological father living out of the household by kindergarten versus in the household, and number of waking hours father spends with the child according to maternal report at kindergarten. None of these variables were associated with any of the child outcome variables.

Contributor Information

Rina D. Eiden, Research Institute on Addictions and Department of Pediatrics, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Ellen P. Edwards, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Kenneth E. Leonard, Departments of Pediatrics and Psychiatry, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Associsation. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Rice J, Endicott J, Reich T, Coryell W. The family history approach to diagnosis: How useful is it? Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:421–429. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800050019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Blackson TC. Temperament: A salient correlate of risk factors for alcohol and drug abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;36:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK. Screening for depression in a community sample: Understanding the discrepancies between depression syndrome and diagnostic scales. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100059010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SJ. Affect regulation and the development of psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X. Linking parenting processes and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:82–94. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kim S, Brown AC. Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Development. 2002;73:1505–1516. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy L, Nagin D, Tremblay R, Bates J, Brame B, Dodge K, et al. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:222–245. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Butovskaya ML, Deminaovitsch AN. Social competence and behavior evaluation (SCBE-30) and socialization values (SVQ): Russian children ages 3 to 6 years. Early Education and Development. 2002;13:153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D, Cisin IH, Crossley H. American drinking practices: A national study of drinking, behavior and attitudes. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1969. (Monograph No 1) [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: A multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:477–498. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: Clinical and developmental issues. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. The parent–child early relational assessment: A factorial validity study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1999;59:821–846. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Musick J, Scott F, Klehr K. The Mothers' Project Rating Scale of Mother–Child Interaction. 1980 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JK, Caspi A, Rutter M, Tomas MP, Moffitt TE. The caregiving environments provided to children by depressed mothers with or without an antisocial history. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1009–1018. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl T, Kim KJ, Scaramella L. Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:143–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1022570107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, Littman C. Autonomy as competence in two year-olds: Maternal correlates of child defiance, compliance and self-assertion. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:961–971. [Google Scholar]

- DeLucia C, Belz A, Chassin L. Do adolescent symptomatology and family environment vary over time with fluctuations in paternal alcohol impairment? Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:207–216. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EP, Eiden RD, Colder CR, Leonard KE. The development of aggression in 18 to 48 month old children of alcoholic parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:409–423. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK. Interpersonal relationships and sex differences in the development of conduct problems. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8:39–63. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-2341-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Chavez F, Leonard KE. Parent–infant interactions in alcoholic and control families. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:745–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Predictors of effortful control among children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:309–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Children's internalization of rules of conduct: Role of parenting in alcoholic families. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:305–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Hoyle RH, Chavez F. A transactional model of parent–infant interactions in alcoholic families. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:350–361. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children's externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Losoya SH, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, et al. The relations of parenting, effortful control, and ego control to children's emotional expressivity. Child Development. 2003;74:875–895. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Liew J. Relations among positive parenting, children's effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development. 2005;76:1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Biringen Z, Clyman RB, Oppenheim D. The moral self of infancy: Affective core and procedural knowledge. Developmental Review. 1991;11:251–270. [Google Scholar]