Abstract

The recent historiography of molecular biology features key technologies, instruments and materials, which offer a different view of the field and its turning points than preceding intellectual and institutional histories. Radioisotopes, in this vein, became essential tools in postwar life science research, including molecular biology, and are here analyzed through their use in experiments on bacteriophage. Isotopes were especially well suited for studying the dynamics of chemical transformation over time, through metabolic pathways or life cycles. Scientists labeled phage with phosphorus-32 in order to trace the transfer of genetic material between parent and progeny in virus reproduction. Initial studies of this type did not resolve the mechanism of generational transfer but unexpectedly gave rise to a new style of molecular radiobiology based on the inactivation of phage by the radioactive decay of incorporated phosphorus-32. These ‘suicide experiments’, a preoccupation of phage researchers in the mid-1950s, reveal how molecular biologists interacted with the traditions and practices of radiation geneticists as well as those of biochemists as they were seeking to demarcate a new field. The routine use of radiolabels to visualize nucleic acids emerged as an enduring feature of molecular biological experimentation.

Keywords: Molecular biology, Radioisotopes, United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Bacteriophage, Radiobiology, Target theory, Hershey–Chase experiment, Meselson–Stahl experiment, Suicide experiments

1. Introduction

In their overview of the history of experimental life sciences Daniel Kevles and Gerald Geison refer to radioactive isotopes as having become ‘sine qua non in molecular biological research, serving as tags for fragments of DNA employed for purposes ranging from basic gene analysis to forensic genetic fingerprinting’ (Kevles & Geison, 1995, p. 101). In this essay I wish to unpack this contention as one facet of a broader study of how the arrival of the atomic age ushered in the commonplace uses of radioisotopes. How and why did radioisotopes become crucial to molecular biology? In what ways did they enable or constrain the visualization of molecular forms of life? How did radioisotopes intersect with other practices and research materials? Did molecular biologists use radioisotopes in distinctive ways, or was there a common epistemology underlying radioisotope usage among biologists in many specializations? Can the history of a particular experimental tool tell us something about the contours of a scientific discipline, or do experimental histories excavate different genealogies and developmental stories?

In the aftermath of World War II, and of the nuclear blasts over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the US government publicized the peacetime benefits of nuclear knowledge. Prominent among the civilian dividends of the atomic age were radioactive isotopes.1 Pioneering biomedical uses of both stable and radioactive isotopic labels had preceded the atomic age by two decades. However, production of radioisotopes remained small scale until the development of nuclear reactors in the 1940s under the auspices of the Manhattan Project. In planning for postwar development of atomic energy, leaders of the American bomb project proposed to convert the large graphite reactor at Oak Ridge into a production site for radionuclides for outside users. The signing into law of the Atomic Energy Act on the first of August 1946 enabled the Manhattan Project to inaugurate this program of isotope distribution, four months before the infrastructure was legally transferred to the newly-established US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). In part because domestic nuclear power failed to be developed in the late 1940s, isotopes became the most conspicuous evidence of the peacetime benefit of nuclear reactors, and thus served a crucial role in legitimating the civilian control of atomic energy (Creager, 2006).

The US government’s program enabled thousands of researchers and physicians to obtain radioisotopes readily and inexpensively. From 1946 to 1955, the AEC sent out nearly 64,000 shipments of radioactive materials to research laboratories, companies, and clinics.2 The American agency also promoted the use of radioisotopes by offering courses to scientists on methods for using radioactive materials and by cooperating with industry to make radiolabeled molecules and radiopharmaceuticals available (Lenoir & Hays, 2000; Creager, 2004). Within a few years of the American program, the British and Canadian atomic energy installations also began providing radioisotopes to scientists and physicians; the British agency encouraged their adoption through its Isotope School (Kraft, 2006; Herran, 2006). Recent scholarship has emphasized the role of these government policies in facilitating the widespread utilization of radioisotopes by postwar scientists, opening up new lines of research in biochemistry, molecular biology, genetics, ecology, and oceanography in the 1950s and 1960s.3

This article focuses on an experimental practice quite central to the coalescing field of molecular biology in the 1950s: the use of radioisotopes as labels in studying the reproduction of bacterial viruses. The most widely cited application of this kind is the Hershey–Chase experiment, in which phosphorus-32 was used to label the phage DNA and sulfur-35 to label the phage protein.4 Subsequent infection with each type of labeled phage showed that only the phosphorus-32-labeled nucleic acid component of the virus entered the bacterial cell to a significant extent (Hershey & Chase, 1952). Up until that point, most biologists assumed that protein, perhaps in conjunction with nucleic acid (as a ‘nucleoprotein’), was the heredity material of living organisms, including viruses.5 Hershey and Chase’s surprising outcome challenged this presumption—their radiolabels traced infectiousness and heredity to the bacteriophage’s DNA.6

As I have emphasized elsewhere, viruses such as bacteriophage and tobacco mosaic virus served as crucial experimental subjects for molecular biologists, on account of their utility for both biochemical and molecular genetic investigations and because virus reproduction was perceived as a signature of life itself (Creager, 2002). The availability of reactor-produced radioisotopes equipped virus researchers (and biochemists more generally) with a valuable new tool. The importance of instrumentation and material culture in the emergence of molecular biology has been an important theme in the historiography, represented by studies of ultracentrifugation, electrophoresis, spectroscopy, electron microscopy, and scintillation counting.7 Whereas much of this literature originated by way of attention to the Rockefeller Foundation’s role in cultivating collaborations between physicists, biochemists, and biologists, increasingly it has been oriented to material epistemology—the way in which technologies and things have shaped the contingent growth of biological knowledge.8

The case of radioisotopes highlights the continuing relevance of scientific patronage to issues of material supply and epistemology. Compared with other the methods and technologies mentioned, what is distinctive about radioisotopes is the way in which their mass-production depended on US government policy regarding atomic energy (Creager, 2004). As Kraft and Strasser have shown, national atomic energy policy and funding programs affected both the availability of radioisotopes and the emergence of molecular biology in Europe (Kraft, 2006; Strasser, 2006). Through producing and distributing radioisotopes to scientists, national atomic energy agencies enabled and encouraged radiolabeling studies and radiation genetics investigations, experimental approaches rapidly taken up by phage researchers but also by laboratory and field biologists working in many other subfields (Creager & Santesmases, 2006). The phage experiments conducted with radiophosphorus suggest that the way in which first generation molecular biologists conceptualized heredity was closely connected to the experimental questions permitted by these radiolabeling techniques—as well as to concerns about radiation hazards (de Chadarevian, 2006; Rheinberger, n.d. a). This episode also reveals that careful analysis of experimental materials and practices can bring into view hitherto-missed scientific preoccupations, even in a well studied discipline.

2. Tracers from studies of photosynthesis to radiolabeled phage

In the early postwar period, both scientists and US government officials viewed the biomedical applications of radioisotopes as falling into two categories: uses of radioisotopes as tracers and uses as sources of radiation, most prominently in medical therapy.9 The distinction played out at several levels. First, in the research contexts, radioisotopes were employed principally as tracers (with a few important exceptions), whereas most of the early clinical uses were aimed at replacing radiation sources such as X-rays and radium with specific radioisotopes. These two classes of application also required vastly different amounts of material—the therapeutic use of an isotope as a radiation source (such as phosphorus-32) could require a thousand-fold greater level of radioactivity than its tracer use. Radioisotopic tracers were especially useful for bringing into view the dynamics of metabolism by tagging particular molecules (Rheinberger, n.d. b). At the biological level, it was the observation that low-level amounts of radiation did not disturb fundamental living processes that legitimated the use of radioisotopic tracers as probes (Kamen, 1951, p. 122). Biologists tended to use radioisotopes either as tracers or as sources of function-perturbing radiation, rarely both.

Tracer applications of radioisotopes secured a broadly biochemical approach to understanding life at the molecular level, and so contributed significantly to the experimental epistemology of molecular biology in the 1950s. For example, the two hallmark experiments of molecular biology in the 1950s, the Hershey–Chase experiment and the Meselson–Stahl experiment, both relied on isotopes to visualize genetic units (Hershey & Chase 1952; Meselsohn & Stahl, 1958).10 Similarly, most physiologists, biochemists, endocrinologists, and ecologists prized radioisotopes for their uses as tracers. By contrast, geneticists and radiobiologists tended to be more interested in reactor-generated radiation sources, including radioisotopes, for what they could reveal about the biological effects of radiation. That said, radioisotopes generally failed to supplant older radiation sources, especially ultraviolet radiation and X-rays, in the study of radiation-induced mutations and cytological effects.

Between these two tracks of investigation with radioactive tracers and radiation sources lies one unusual example of their integration into a single line of experimentation: that of using phosphorus-32 to study bacteriophage growth, which blossomed into the ‘suicide experiments’ of the 1950s and 1960s. These experiments enabled the tracing of specific molecules—namely phage genes—by inactivating them. The approach arose unexpectedly out of the use of newly available isotopes as tracers. At a time when following the infection and reproduction of phage in the bacterial cell was of crucial interest to molecular biologists, radioisotopes provided a way for researchers to track the movement of molecules from one viral particle to another. But phosphorus-32 also served as the intracellular radiation source for a new kind of radiobiology experiment in which the distribution of the radioisotope in phage particles over time could be registered by the survival curves. Phosphorus-32 had an unusual, perhaps even unique, use as both a label and a radiation source, and in both modes it could illuminate the status of reproducing viral particles over time.

Radiobiological approaches to phage began early. In the early 1920s, two different scientists reported that the infectivity of bacterial viruses could be destroyed by irradiation.11 These observations were followed up in the 1930s with ‘target theory’ experiments with phage.12 Such experiments generally involved treating the virus particles as targets of radiation, and plotting survival as a function of radiation dosage (usually duration of exposure to the source of radiation). In a ‘one hit’ type of response, in which the particle behaves as a single, susceptible target, the plot of the logarithm of the number of survivors against dosage yields a straight line.13 The survival of T-phages after exposure to ultraviolet radiation was studied intensively throughout the 1940s, as was virus inactivation with X-rays, g rays, a rays, electrons, neutrons, and deuterons. Not all these radiation agents acted directly on the virus.14 Studies of X-ray inactivation of a variety of viruses (first papilloma virus, then bacteriophage, then plant viruses) showed the effects of this agent to be indirect, resulting from the free radicals generated by ionizing radiation. Indirect effects were distinguished by direct effects on the basis of whether alterations of the medium could be made to protect the phage—as Salvador Luria put it, ‘a direct effect of ionizing radiations is defined as a “nonprotectable” effect’ (Luria, 1955, p. 337).15

More proximally, the discovery of phage ‘suicide’ by radioactive decay was an outgrowth of research on photosynthesis in Martin Kamen’s laboratory at Washington University in St. Louis. Kamen’s graduate student Howard Gest was using cyclotron-produced phosphorus-32 as a tracer to test Sam Ruben’s hypothesis that ‘in photosynthesis, light energy is converted to chemical energy in the form of ‘high energy phosphate compounds’ (Gest, 2002, p. 333; Ruben, 1943).16 Gest studied the uptake of radiolabeled inorganic phosphate (Pi) in three species of phosphosynthetic bacteria and algae, and found that all three organisms took up more Pi when illuminated. Gest conjectured that this inorganic phosphate was converted to low molecular weight organic phosphoryl compounds, which in turn were precursors of energy-rich phosphoryl compounds such as ATP. Unfortunately for Gest, experiments by Melvin Calvin did not confirm their findings, although Calvin’s results were later disproven. Gest turned to investigate bacteriophage, bringing his skills and interest in using radiophosphorus as a tracer.

Gest possessed a background in phage research, a field that had begun to interest him as a college student at UCLA in 1940. He had worked as a research assistant to Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria during the summers at Cold Spring Harbor in 1941 and 1942 and began doctoral research with Delbrück at Vanderbilt in the fall of 1942. The war effort interrupted his studies, and he worked as a chemist for the Manhattan Project investigating uranium fission products, first in Chicago then at Oak Ridge. In 1946, he resumed his graduate studies at Washington University with Kamen on account of his expertise in radiochemistry.17 His continuing interest in phage was no doubt encouraged by the presence at Washington University of Alfred Hershey as an Associate Professor of Bacteriology and Immunology.

Phage researchers at several institutions had already begun using radioactive labels generated by cyclotrons. At the University of Chicago, Frank Putnam and Lloyd Kozloff labeled T6 bacteriophage by growing them in the presence of phosphorus-32. When they subsequently infected unlabeled E. coli (in unlabeled broth) with this ‘hot’ phage, they could track the movement of the phosphorus. What they found was that nearly 70% of the phosphorus in progeny phage came from the medium, presumably through a bacterial pathway (Putnam & Kozloff, 1948; Kozloff & Putnam, 1950; Putnam & Kozloff, 1950). However, their experiments did not settle what happened to the atoms of an individual virus during replication. As Ole Maaløe and James Watson put it, the biochemical problem of reproduction could be seen in the fact that atoms do not reproduce but genes do (Maaløe & Watson, 1951). Where do the atoms that form new genes come from?18 For a generation of biologists, the problem of virus reproduction seemed to hold the key to understanding the nature of the gene, and radioisotopes offered a tantalizing molecular flashlight for examining the process.

Building on his familiarity with phosphorylated compounds and their metabolism, Gest—in collaboration with both Hershey and Kamen—designed an experiment to ‘trace the fate of radioactive phosphorus in a single phage particle during its multiplication in a single E. coli cell’ (Gest, 2002, p. 335). They sought to determine whether radioactive phosphorus would be transferred from parental phage to its progeny or whether it would remain in the original phage particle. They obtained phosphorus-32 of high specific radioactivity from the AEC’s facility at Oak Ridge to label a strain of T2 phage that Hershey worked with. The 32P-labeled phage was highly radioactive, and it turned out that Hershey’s teaching duties postponed the infection experiment by a few weeks. This delay proved significant. Re-assaying the radioactivity and phage titer before beginning the actual experiment, Gest and Hershey were dismayed to find that the phage titer had decreased significantly. Another test a few weeks later showed a further decline in phage titer. As Gest relates the story, ‘Finally, it dawned on us that a certain number of 32P disintegrations within a phage particle leads to biological inactivation. We had accidentally discovered the phenomenon of phage ‘suicide’ caused by 32P b-decay’ (Gest, 2002, p. 335).

The goal of their collaboration thus shifted from following the dynamics of phosphorus transfer during infection to studying the survival rate of 32P-labeled phage. As Hershey, Kamen, Gest, and J. W. Kennedy reported in their paper, their assays gave two kinds of information: the rate of inactivation indicated the specific activity of the radiophosphorus in phage, and the survivor curve shed light on how the radioactivity was distributed within the phage population (Hershey, Kamen et al., 1951, p. 305). They argued that their results could be best understood as compatible with a simple assumption: ‘The inactivation of a radioactive phage particle is the consequence of the disintegration of a single atom (not necessarily the first) of its assimilated 32P’ (ibid., p. 308). The infectivity of the population of radiolabeled phage declined exponentially over time; the rate was proportional to the concentration of phosphorus-32 in the original labeling medium. From their study of the radiosensitivity of 32P-labeled T4 phages, the authors determined that about one in ten hits was lethal (ibid., p. 315). The low efficiency of inactivation suggested that the phage were killed as a direct result of the nuclear reaction. But this did not resolve the exact cause of death, which could be attributable to any one of several effects of phosphorus-32 decay: the release of energy, the absorption by the nucleus of the 30 electron volts released, other energy dissipation associated with the rearranged electrons, or the fact that a sulfur atom was left in the place of the phosphorus (ibid., p. 316).

In their 1951 paper, Hershey, Kamen et al. inferred that at least a ‘fraction of the phosphorus atoms of the phage particle is situated in vital structure, and therefore that the vital structures contain nucleic acid’ (ibid., p. 317). It was this issue of identifying the nature of ‘vital structures’ with radioisotopic tracers that Hershey embarked upon in 1950 when he took up his new post in the Department of Genetics at Cold Spring Harbor, using radiophosphorus and radiosulfur purchased from Oak Ridge.

3. The Hershey–Chase experiment

Hershey wrote in his 1950–1951 research report, ‘If . . . labeled atoms were transferred in the form of special hereditary material, the progeny of a first cycle of growth from radioactive seed would contain radioactive atoms principally in this special material. During a second cycle of growth, therefore, radioactivity should be more efficiently conserved’.19 In fact, this line of experimentation was already underway in Copenhagen. In 1951, Ole Maaløe and James Watson published the results of an experiment designed to follow 32P-labeled phage through two generations. As mentioned, Putnam and Kozloff had already demonstrated that 30% of the isotopic label was transferred from parent to progeny phage, but the localization and distribution of this label in the progeny was not clear. They suggested that the phage might be composed both genetic and non-genetic components, each of which were labeled with phosphorus-32. The portion that was not transferred to the next generation would then be the non-genetic portion of the virus. At the 1950 summer phage meeting at Cold Spring Harbor, Seymour Cohen noted that this hypothesis could be tested by taking the labeled phage to a second generation; Maaløe and Watson referred to this idea as the ‘second generation experiment’, and it inspired their study (Maaløe & Watson, 1951, p. 509).

What Maaløe and Watson found was that 30% of the isotopic label was transferred from the progeny of the first infection to the second generation. This meant that the phosphorus was similarly localized in both the parents and the progeny. Since the original radioactive phage particles were presumably uniformly labeled, their progeny must also be uniformly labeled. This ruled out Kozloff and Putnam’s suggestion that some of the phosphorus-32 might be labeling a genetic portion of the virus, and some a non-genetic part, such that the 30% represented the label on the genetic portion that was transferred. But, as Maaløe and Watson qualified, their experiment addressed only the fate of the phosphorus atoms. ‘A different answer might be obtained with a label like sulfur, that would label specifically the protein moiety of the phage’ (ibid., p. 508).

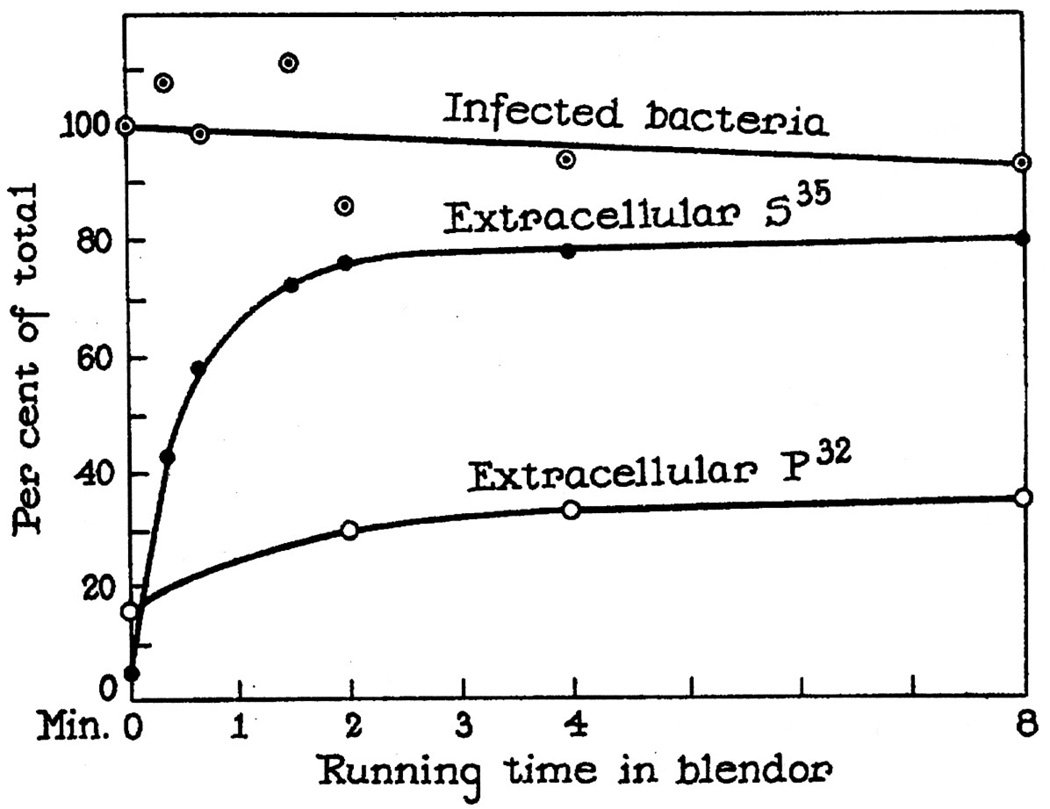

This is exactly what Hershey did with his technician Martha Chase, resulting in their celebrated paper, ‘Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage’ (Hershey & Chase, 1952).20 Drawing on his group’s labeling experiments, Kozloff had referred to the genetic part of bacteriophage as a ‘nucleoprotein’, and argued that whatever transfer of label occurred from parent to progeny was non-specific in nature (Kozloff, 1952, p. 106).21 Hershey’s own preliminary experiments using sulfur-35 to label parental phage protein showed that about a third of the label from either 35S-labeled parental protein ended up in phage progeny, about the same amount as 32P-labeled parental DNA that was transferred (Hershey, Roesel et al., 1951).22 These early trials by Hershey did not suggest a special role for nucleic acid. Hershey and Chase’s experiment reinvestigated this issue and, even more significantly, brought a new technique into play: the use of a kitchen blender. Blending infected cultures disrupted the attachment of phage to the outside of bacterial cells, so that intracellular virus particles and extracellular virus particles could be physically separated. The blender experiment revealed a dramatic difference between the transfer of labeled phage protein and that of phage nucleic acid: 80% of the 35S-labeled phage protein remained outside the bacterial cells (and so was agitated off by the blender and recovered in the supernatant), as compared with only 30% of the 32P-labeled DNA (see Fig. 1). The other 70% of labeled viral DNA was within the cells, having entered the bacteria shortly after phage adsorption.23

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram showing removal of sulfur-35 and phosphorus-32 from bacteria infected with radioactive phage, and survival of the infected bacteria, during agitation in a Waring blendor (diagram and caption from Hershey & Chase, 1952, p. 47; © 1952 A. D. Hershey & M. Chase).

Based on the amount of each label that entered the bacterial cell in their experiments with phosphorus-32 and sulfur-35, Hershey and Chase suggested that the viral DNA was the active agent of phage reproduction.24 Hershey himself was surprised by this outcome.25 He drew out its implications clearly: The bacteriophage should no longer be regarded as an indivisible unit—and should not be called a nucleoprotein, as had been conventional among virus researchers for more than a decade (Hershey, 1953, p. 99). The protein and nucleic acid had clearly delineated biological roles. Hershey referred to the protein as the ‘membrane’, that surrounds, carries, and delivers phage’s genetic material, solely nucleic acid. His ideas along this line were inspired by Thomas Anderson’s electron micrographs of phage particles attached by their tails to bacterial cells, as well as by Roger Herriott’s finding that osmotic shock could release phage DNA into solution leaving ‘ghosts’ behind (Anderson, 1951; Herriott, 1951). Hershey inferred that the phage protein is ‘confined to a protective coat that is responsible for the adsorption to bacteria, and functions as an instrument for the injection of phage DNA into the cell’ (Hershey & Chase, 1952, p. 56). Hershey said less about the fate of the phage DNA after infection: ‘parental DNA components are, and parental membrane [protein] components are not, materially conserved during reproduction. Whether this result has any fundamental significance is not yet clear’ (Hershey, 1953, pp. 110–111).

4. Suicide experimenters of the 1950s

4.1. From transfer experiments to radiation survival curves

In the mid-1950s, Hershey continued to pursue the question of material transfer from parent to progeny through use of phosphorus-32 as a tracer (Hershey, 1954; Hershey & Burgi, 1956). Others in the phage group turned to exploiting the isotope’s radiobiological potential.26 This style of experiment seems to have been especially attractive to those phage workers who came from the physical sciences (e.g., Gunther Stent, Cyrus Levinthal, Seymour Benzer), perhaps because it continued the line of research associated with target theory, itself an application of physics.27 In particular, researchers emulated the state-of-the-art phage experiments with ultraviolet radiation using incorporated phosphorus-32. In doing so, they sought to determine whether key genetic discoveries with UV-irradiated phage, such as multiplicity reactivation, cross-reactivation, and photoreactivation, could also be observed with radiation from phosphorus-32.28 These experiments were aimed, in other words, at using biophysical tools to answer fundamental questions about the nature of the gene. After World War II, most such investigations related either directly or indirectly to concerns about the genetic hazards of radiation, research supported by national governments as part of efforts to develop atomic energy.29

In 1952, geneticist Guido Pontecorvo observed that one could define the gene as a unit of recombination, a unit of mutation, or a unit of physiological activity (Pontecorvo, 1952). Each was valid but in certain cases discrepancies arose, and the inconsistencies were most pronounced at the level in which genetics and biochemistry intersected. Many of the biophysically minded phage researchers sought to apprehend genes as physical entities, precisely in this realm of ambiguity.30 One experiment that figured prominently in this arena of phage radiobiology was that of Luria and Raymond Latarjet, in which bacteria already infected with phage were exposed to various doses of radiation, to assess the radiosensitivity of phage that was already in the process of reproduction (Luria & Latarjet, 1947).31 They found that the sensitivity of T2 phage to ultraviolet radiation decreased significantly in the early infection period, then later became multiple-target in character, and finally showed an increase again in ultraviolet sensitivity. Seymour Benzer repeated this experiment with T7 phage, since unlike in case of T2, it did not show multiplicity reactivation (genetic recombination between inactivated phage particles). The results were more straightforward than Luria and Latarjet’s: there appeared ‘simply an increase with time of the average number of targets per cell, each target being similar radiologically to a T7 particle’ (Benzer, 1952, p. 69). Yet even when results accorded with target theory, as in this case, it proved difficult to pinpoint the character of the gene using the tools of radiation biology.

Gunther Stent first began to experiment with 32P-labeled phage while on a postdoctoral fellowship in Copenhagen during 1950–1951 with Herman Kalckar. After leaving Nazi Germany in 1940, Stent completed a Ph.D. in physical chemistry at the University of Illinois before becoming interested in phage research. His project in Copenhagen was aimed at investigating ‘by means of radioactive tracers the kinetics of the processes by which the virus-infected host cell assimilates phosphorus and incorporates it into bacteriophage material’.32 Stent collaborated with Maaløe, following up Watson and Maaløe’s work on second-generation phage label transfer experiments. They used phosphorus-32 to show that there existed phosphorus-containing ‘phage-like structures’ before the release of infectious viruses, which were identified through sedimentation in the centrifuge, adsorption into sensitive bacteria, and precipitation with antiphage serum (Maaløe & Stent, 1952).

In one respect, this was a new approach to an old problem: Delbrück and Luria had attempted in their initial collaborative experiments to use superinfection with more than one kind of bacteriophage to capture and analyze viral replication intermediates. They reasoned that if they could infect a suitable host with two different phages, one might lyse the bacteria while the other was in the process of reproducing, revealing an ‘intermediate stage of virus growth’ usually hidden within the cell (Delbrück & Luria, 1942, p. 111). Instead, as Hershey put it a few years later, ‘this experiment led into a number of still half-explored byways, and eventually to the discovery of genetic recombination of viruses’ (Hershey, 1952, p. 125). Their joint experiments along this line also revealed the phenomenon of interference—that infection with one bacteriophage could prevent altogether infection by the second.33 However, it did not make visible the mode of reproduction of bacteriophage. Radiolabeling seemed to offer another, more promising, way to visualize the intermediate stages of virus replication. In the fall of 1952, Stent continued this use of radiolabels to investigate intracellular phage development at Berkeley, where he joined Wendell Stanley’s Virus Laboratory. As Stent put it in a summary for the Microbial Genetics Bulletin: ‘I am engaged in a study of the replication of the nucleic acids of bacteriophages by means of radioactive tracers, as well as searching for effects of the transmutation of radiophosphorus on the genetic character of bacteriophages into which it has been incorporated’.34

Cyrus Levinthal, a physicist-turned-phage researcher, set up a similar research program at University of Michigan, to follow up observations using ultraviolet radiation of multiplicity reactivation. His correspondence with Stent reveals just how hard it was to get these kinds of experiments with radioactive phosphorus working. This was in part due to the challenges of getting sufficient quantities of ‘carrier-free’ phosphorus-32 with high enough specific activity. (Stent ended up importing the radionuclide from the British atomic energy installation in Harwell, England, though he continued to have problems with both the quality of material and the speed of delivery.35) As Levinthal cautioned Stent, ‘If our experiments are any indication, your problems with the suicide experiments will not be entirely over when you get the high specific activity 32P’.36

Stent did manage to get the bacteriophage suicide studies working early in 1953. He viewed these experiments with ‘super 32P-hot T2 and T3’ as ‘something like a cross between the Hershey, Kamen, Kennedy and Gest and the Luria–Latarjet experiments’.37 Stent was combining various phage mutants, labeled or not with phosphorus-32, and analyzing the mixed infections over time, freezing aliquots in liquid nitrogen at various time-points. The ‘eclipse’ period of bacteriophage infection for T2 was a brief thirteen minutes, whereas the half-life of phosphorus-32 was fourteen days.38 Thus one had to slow down the replication process—by freezing the infected cells in liquid nitrogen—to allow the radioactive decay to occur, a process unaffected by temperature. The aim was to assess how phage mortality due to radioactive decay varied over the course of the viral reproduction process, as a way to ascertain when in this cycle the infecting phage is genetically vulnerable.

This approach drew on the earlier radiolabel transfer experiments (as developed by Hershey, by Kozloff and Putnam, and by Watson and Maaløe), with a twist: here the experimental design was aimed at assessing the genetic effects of the radiolabel rather than simply following its movement from infecting virus to progeny. As Stent put it in his paper at the 1953 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium:

Hershey and Chase (1952) have shown that when T2 bacteriophage infects a sensitive bacterium, most of the viral nucleic acid enters the host cell, whereas most of the viral protein remains without. Hence it may be thought that the nucleic acid is the structure which presides over the replication of the infecting particle. The experiments . . . have been designed to answer the question of how long after infection the parental nucleic acid still continues to preside in this way, or restating the question in another way, of how soon after infection the parental nucleic acid has accomplished it mission. (Stent, 1953a, p. 256)

Stent’s mixed infections also allowed for recombination between different mutants, enabling him to assess marker rescue from inactivated phage. But this also meant that his experiments had many variables in play at the same time. As Stent wrote Gus Doermann (who was working on analogous experiments with ultraviolet radiation at Oak Ridge), ‘I have done one Gargantuan experiment so far, permitting phage growth for 0, 3, 5, and 7 minutes before freezing everything and analyzing the plaque types before and after burst from all the samples from day to day. The results are very interesting, I am sure, but I can’t say that I have been able to figure them out’.39 Doermann wrote Stent back, on behalf of himself and his graduate student Franklin Stahl, ‘that we working on closely related problems, and our results agree very well’.40

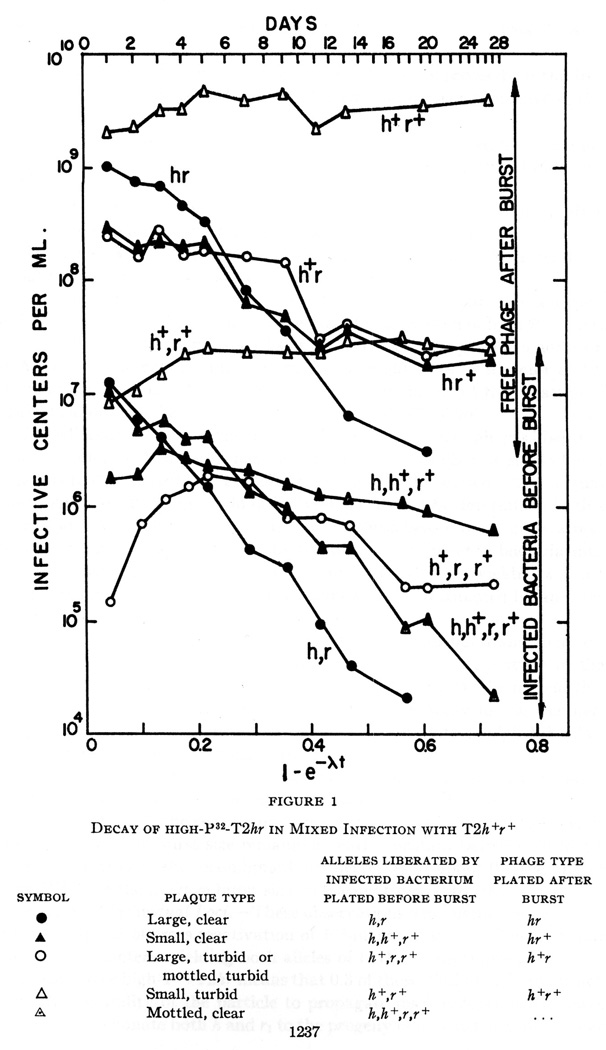

By the fall of 1953, Stent had obtained results suggesting he could knock out individual genetic loci with radioactive labeling of phage T2 in his ‘genetic-cum-P32 suicide work’.41 He infected bacteria first with a nonradioactive strain of T2 (T2h+r+), second with another strain of 32P-unstable T2 phage (T2hr), then he looked at the genetic markers in surviving phage (Stent, 1953b). Focusing on specific loci rather than simply phage viability had made the experiments even more complex to execute (see Fig. 2). As Stent put it in a letter to Levinthal, ‘Unfortunately, the significant experiments have to be done in single burst, and at late stages of the decay, perhaps only one in ten bursts is one of interest; the experiments are therefore, frightfully cumbersome, besides lasting a month or so’ (ibid.). Stent contended that the phosphorus-32 incorporated in the phage DNA could inactivate specific genetic loci, just as exogenous X-ray exposure could (as shown by Doermann); this drew some skepticism from Hershey.42 Nonetheless, in a publication on these early results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Stent asserted that ‘the elimination of h and rI loci by P32 decay are independent events’ (ibid., p. 1239).

Fig. 2.

Figure depicting the decay of highly-labeled 32P-T2hr in mixed infection with T2h+r+ (reproduced from Stent, 1953b, p. 1237).

These mating experiments exploited the genetic effects of radioactive decay more than the tracing capabilities of the isotope label. But Stent also continued some tracing experiments in the vein of Maaløe and Watson by collaborating with Howard Schachman and Itaru Watanabe on the fate of parental phosphorus during viral multiplication. They used both biophysical and biochemical techniques to follow phage DNA—by ultracentrifuging the contents of the infected bacterial cells they determined when phage-like particles were detectable, and by assaying the TCA solubility of 32P-containing DNA in conjunction with DNase digestion, they assessed when and whether the radiolabeled DNA remained in the form of high molecular weight fibers or lower molecular weight pieces. They found that much of the parental phosphorus remained associated with high molecular weight DNA through the ‘eclipse’ period, so that direct transfer of phosphorus-32 from parent to progeny was possible.

Watanabe, Stent, and Schachman pointed out that their transfer experiments were compatible with the recent Watson–Crick double-helical model for DNA, already an important point of reference.43 As they asserted, ‘one is at liberty to suppose that replication of bacteriophage DNA occurs by means of a process, such as that proposed by Watson and Crick in which there is a direct material continuity between parent and daughter structures’ (Watanabe et al., 1954, p. 47). But their results also failed to rule out other alternatives. Some DNA from the infecting particles was broken down into low molecular weight material, keeping alive the possibility of indirect transfer, in which the progeny are synthesized from existing small molecules in the cell. The question of generational transfer thus remained unresolved. As Stent wrote Latarjet, ‘I am always chasing after that elusive problem of the fate of the phosphorus of a parental DNA molecule during its replication and still have not given up hope’.44

The possibility of using radiolabels to trace an atom in a virus’s genetic material through the life cycle remained alluring, despite the meager results that had been obtained. The Watson–Crick double helix provided phage researchers with a concrete model for imagining how transfer of material during DNA replication might proceed. There were methodological limits: Radiolabels enabled researchers to visualize genes in terms of points (wherever the radioactive atom was incorporated), but not wholes, and despite the sensitivity of the technique, one could not necessarily discern whether the transfer of a label was tracing reproduction, recombination, disintegration and reassimilation, or some combination. Nonetheless, this approach reinforced the tendency among biophysicists to think of reproduction as a molecular—rather than organismal—process.

4.2. Phophorus-32 mortality in the host cell

Stent continued with suicide experiments, and began to perform some experiments in which the bacteria rather than the bacteriophage were labeled with phosphorus-32. By growing ‘cold’ phage in ‘hot’ bacteria, he determined that the incorporation of radiophosphorus from the host cell or media led to an increased instability (due to incorporation of radioactive phosphorus) of progeny phage. However, the increase in radiosensitivity observed in the complexes of cold phage and hot bacteria was not equivalent to the decrease in sensitivity of the hot phage-cold bacteria complexes. Was the observed insensitivity to phosphorus-32 when the label was taken up from host or media ‘related to the fact that the infecting parental DNA had been non-radioactive’, and thus the transfer of material itself protected the progeny (Stent, 1955, p. 859)? To answer this question, Stent set up third experiment, in which both the phage and the bacterial culture were labeled with radiophosphorus (the ‘hot on hot’ experiment).45 In this experiment, both parent and progeny phage were inactivated by the phosphorus-32 decay, but there still emerged ‘a gradual resistance to P32 decay’ (ibid., p. 861). This result was strikingly different than that with ultraviolet radiation, for which sensitivity late in the reproduction cycle yielded survival curves consistent with multiple hits. As Stent wrote Benzer despondently:

The state of my depression is caused by the outcome of that last experiment, hot phage on hot bacteria, which was to prove the non-distribution of parental P during replication. . . . It appears, then, that it makes no difference to the P32 mortality during the latent period as to whether the bacteria are hot or cold, since the reduction in mortality in the present experiment goes at the same rate as in the experiment I presented at CSH last year where cold bacteria were infected with hot T2. This, taken together with my finding that where cold T2 grows on hot bacteria there is never any instability until the progeny are released, then leaves me completely up in the air. I [am] almost driven to the unpleasant conclusion that the DNA ‘transfers its information’ to some non-DNA material (i.e., material not sensitive to UV or P32 decay) during its development.46

Stent’s official conclusion was thus equivocal: ‘Neither the non-radioactivity of the bacterial host cells in Experiment I nor the non-radioactivity of the parental DNA in Experiment II were, therefore, the factors responsible for final stability observed in those experiment. It appears, rather, that a more general process of stabilization to inactivation by P32 decay makes its appearance in the course of the eclipse period’ (Stent, 1955, p. 861). For unknown reasons, the nucleic acid of vegetative phage was simply more refractory than expected to inactivation by radioactive decay. This was a disappointing result given the labor entailed and the elegance of the experimental design. It represented something of a dead end; as Stent confessed to Hershey, ‘I probably can’t study DNA duplication by this technique’.47

Even so, the US AEC found Stent’s ongoing project sufficiently promising to offer him research support for radioisotopes beginning in 1955.48 During this same time period the AEC launched an extensive extramural grants program for genetics, through which it supported, during the fifties, almost 50% of federally funded research in this field (Beatty, 1999). The agency was especially interested in using results from radiation genetics to establish a ‘safe’ threshold low-level radiation, given ongoing atomic weapons testing and emerging public concerns about the safety of radioactive fallout (Jolly, 2004; Rader, 2004).49 Biophysicists aimed to understand the sensitivity of genes to radiation in molecular terms. Stent’s continued studies of bacteriophage suicide led him to offer a mechanism for the lethality of incorporated phosphorus-32 to DNA. Because, according to the Watson–Crick model, DNA is double-stranded, a single break in the polynucleotide backbone—due to either the replacement of a phosphorus-32 atom by sulfur-32 upon radioactive decay or the energy released by the decay—would not disrupt the DNA molecule. But a second break across from the first would break the double-helical chain (Stent & Fuerst, 1955, pp. 454–456). Stent ventured that X-ray ionization inactivated bacteriophage in a similar way, by disrupting the DNA double helix; this was soon substantiated by Stahl (Stahl, 1956).

Stent and his graduate student Clarence Fuerst extended the principle of phosphorus-32 suicide from bacteriophage to bacteria, showing that incorporation of the label at sufficiently high activities could kill bacterial cells (Fuerst & Stent, 1956). As in the case of the bacteriophage experiments, this suicide investigation aimed at shedding light on the nature of genetic reproduction, in this case the partitioning of the bacteria’s DNA between daughter cells. Fuerst and Stent’s questions in this vein were reminiscent of those posed by Watson and Maaløe about phage:

It has been shown that the DNA of E. coli cells retains its phosphorus atoms throughout subsequent bacterial growth and multiplication. How are these phosphorus atoms distributed over the nuclei of daughter cells? Do some descendant nuclei contain only atoms assimilated de novo and are others endowed exclusively with phosphorus atoms of parental origin, or are the atoms of the parental nucleus dispersed among all the nuclei in its line of descendance? The fact that it is the decay of DNA-P32 atoms which is mainly responsible for the death of the bacterial cells offers a method of resolving this question. (Fuerst & Stent, 1956, p. 84)

Fuerst and Stent found that the bacterial DNA was transferred from parent cells to daughter cells in such a way that ‘newly assimilated DNA-phosphorus atoms become intermingled within daughter nuclei’, but the dispersal of the radioactive label shed no further light on the mechanism of replication (ibid., pp. 86–87; original italics).50 In related experiments, Stent and Niels Jerne showed that phosphorus from a parent phage during a single cycle of infection was transferred to between eight and twenty-five progeny. Such a heterogeneous distribution of label defied any simple replication models (Stent & Jerne, 1955).

Stent also undertook experiments to look at third generation transfer of phosphorus-32 in bacteriophage from parent to progeny. He and his coauthors found that radioactive disintegrations in the second generation attenuated the appearance of the label in the ‘grandchildren’ phage, just as occurred between the first and second generations (Stent et al., 1959). In an article with Delbrück, Stent schematized their findings as follows:

Parent (label = 100) → 1st progeny (label = 5) →

2nd progeny (label = 25) → 3rd progeny (label = 12)

Delbrück and Stent attributed the incomplete transfer at each generation to ‘random losses experienced by the entire parental DNA in the course of the infection, replication, and maturation processes’ (Delbrück & Stent, 1957, p. 716).

Taking the work in another direction, Stent and Fuerst used phosphorus-32 incorporation to examine the reproduction of temperate bacterial viruses, such as one found in lysogenic bacteria (Stent & Fuerst, 1956). Fuerst took this approach with him to his postdoctoral fellowship at the Institut Pasteur, where he studied lysogeny and bacterial mating in collaboration with François Jacob and Elie Wollman. Their collaboration was aimed at using suicide experiments to discern the intracellular location of latent virus, or prophage, though the results of the initial experiments, conducted with both inducible and non-inducible phages, proved complex to interpret.51 Jacob, Wollman, and Fuerst also used phosphorus-32 to study the effects of decay inactivation on bacterial mating with Hfr and F− strains (Fuerst, Jacob & Wollman, 1956; Stent, Fuerst & Jacob, 1957).52 They found that phosphorus-32 decay in a radiolabeled Hfr donor cell could disrupt marker transfer to the recipient cell in much the same way as interruption of mating by mechanical means. In addition, phosphorus-32 decay after transfer could inactivate the donated ‘hot’ gene in the ‘cold’ cell just as it would have in the original donor.53 When they looked at the rate of inactivation caused by radioactive decay for different markers, they found that the ‘further a marker was located from the leading extremity of the donor chromosome (O), the more rapidly is it excluded from recombinants’ (Hayes, 1964, p. 591). In other words, the distance between genes could effectively be measured in terms of phosphorus-32 decay (Jacob & Wollman, 1961, pp. 215–218). These suicide experiments provided elegant physical evidence for the transfer of linear DNA during conjugation.

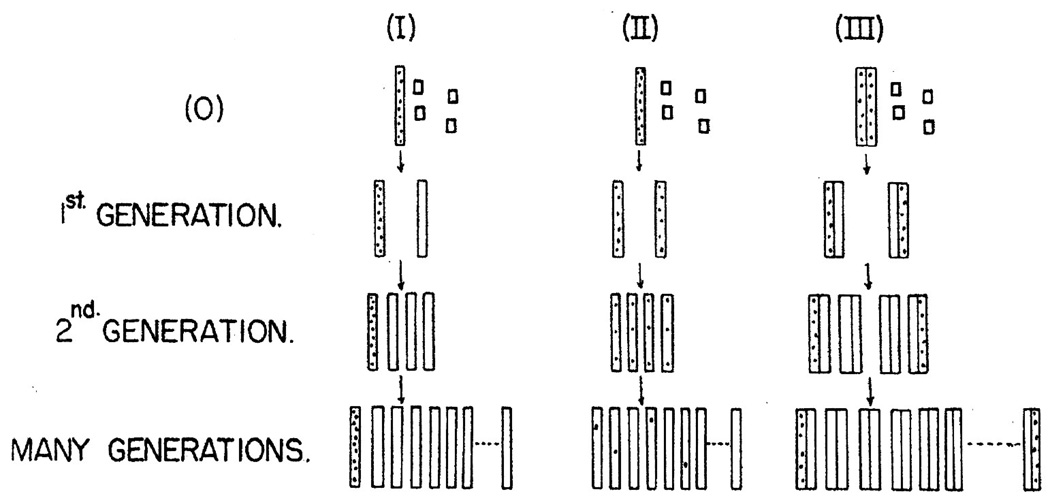

However, the original question of parent-to-progeny transfer in phage continued to be tied up with (and one might be tempted to say, in retrospect, confounded by) research on genetic markers and recombination. In 1956 and 1957, Levinthal and Stent were disputing (drawing also on Hershey’s experiments) whether the transfer of genetic material from phage parents to progeny occurred in big pieces (i.e., the phage chromosome) linked to genetic markers (Levinthal’s view), or whether the original genetic material was dispersed in the course of phage reproduction (Stent’s view).54 In 1956, Levinthal published a paper laying out three models for how parent DNA might be distributed to progeny: (I) template-type replication; (II) dispersive replication; and (III) complementary replication (renamed semi-conservative replication)55 (see Fig. 3). The fact that recombination occurred as well as DNA replication in the case of phage reproduction complicated experimental tests of these models. Levinthal remained convinced that the DNA of T-even phages was bipartite, consisting of one large piece and many (ten to twenty) smaller molecules (Stent, 1963, p. 67).

Fig. 3.

Levinthal’s depiction of three models for DNA replication. The dots represent the radioactive label, and the open squares represent the nonradioactive subunits used to build the new structure. (O) is the original labeled molecule. I is template-type replication (later called conservative) which leaves the label in one molecule; II is a dispersive type of replication, as proposed by Max Delbrück, and III is a complementary type of replication (later termed semi-conservative), as suggested by James D. Watson an F. H. C. Crick (figure and legend from Levinthal, 1956, p. 395).

4.3 Detecting replication: The Meselsohn–Stahl experiment and autoradiography

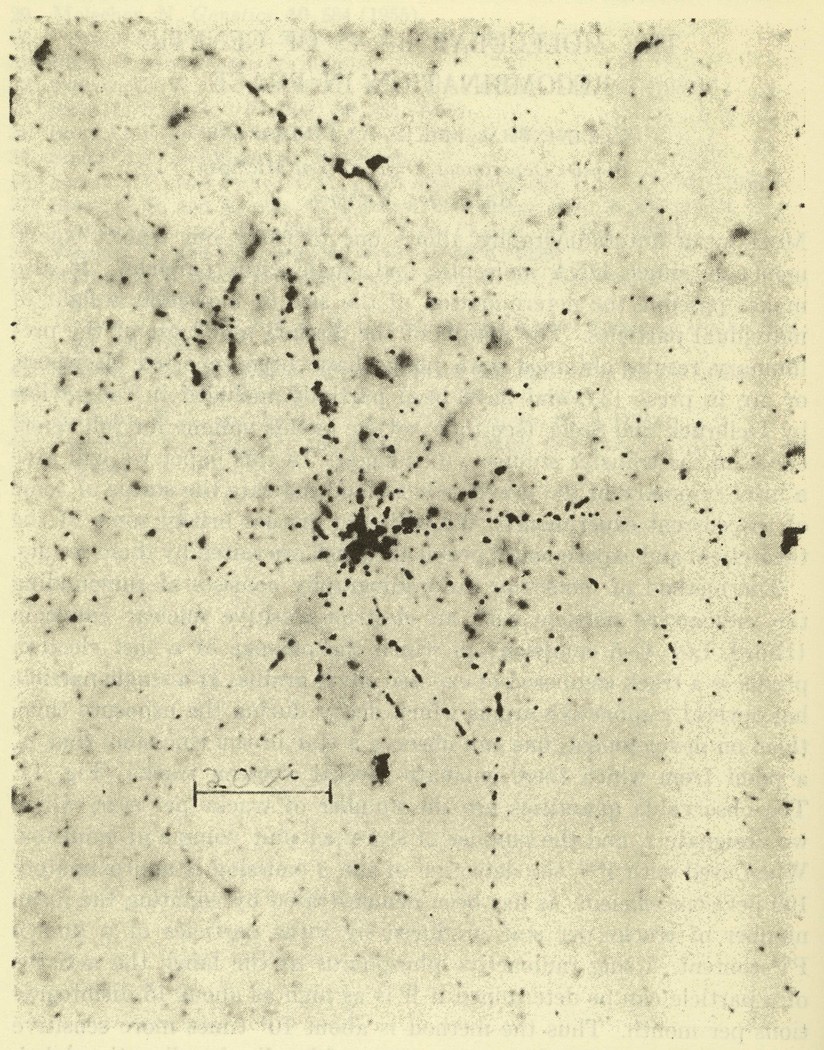

Levinthal developed a method for detecting the distribution of phosphorus-32 in nucleic acid—by exposing individual labeled phage particles to photographic emulsion to produce tracks on an autoradiograph (Levinthal & Thomas, 1957a).56 Decay of phosphorus-32 incorporated into DNA, as point sources, left star-shaped figures in the film; the number of tracks per star gave information about the number of radioactive phosphorus atoms in that source (see Fig. 4.). Analyzing labeled phage through two generations, Levinthal counted the number of tracks per star and the variation of distribution to determine how much phosphorus-32 had been transferred. He found a few individuals among phage progeny that possessed about 20% of the 32P-label of the parent. The mechanism through which these highly labeled progeny were produced remained unclear, but the technique allowed for analysis of transfer to individual particles (Levinthal, 1956).

Fig. 4.

Photomicrograph of star-shaped tracks from the decay of phosphorus-32 atoms incorporated into T-even phage DNA. This image was taken with an objective of N.A. 1.32. Only a small fraction of the tracks can be seen at one focal setting. For counting purposes individual tracks must be followed by changing the fine focus control (image and caption from Levinthal & Thomas, 1957b, p. 738; © 1957 The Johns Hopkins University Press; reprinted with permission).

In the end, the question of transfer of material from parent to progeny was settled decisively by a transfer experiment that used neither phage nor a radioactive isotope.57 In 1957, Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl used the heavy isotope nitrogen-15 to label the DNA of synchronized E. coli (i.e., the cells in the culture would divide at the same time) and followed the labeled nucleic acid in a cesium chloride gradient in the ultracentrifuge, where the mass difference between nitrogen-15 and nitrogen-14 enabled a differentiation between parental and progeny in the sedimentation pattern. Meselson and Stahl introduced their paper with reference to the isotope transfer experiments: ‘Radioisotopic labels have been employed in experiments bearing on the distribution of parental atoms among progeny molecules in several organisms’ (Meselson & Stahl, 1958, p. 671). In part because E. coli reproduced without recombination, unlike the phage in the suicide experiments, Meselson and Stahl could discern a clear pattern of semi-conservative DNA replication (Holmes, 2001).

Suicide experiments continued well after Meselson and Stahl’s experiment—and were inspired by it. In 1960, Werner Arber carried out suicide experiments on lysogenic phage 1P1; his results provided clear evidence that this phage replicates semi-conservatively and also laid the groundwork for Arber’s discovery of restriction endonucleases (Strasser, n.d.). Stent wrote of Arber’s result: ‘At last some useful information to be extracted from a suicide experiment! I think this is the first example of a meaningful conclusion from 32P decay’.58 Levinthal’s use of autoradiography to detect radiolabeled nucleic acid was even more consequential. Whereas he focused on counting tracks to get quantitative and statistical evidence about the distribution of the radiolabel, others imagined more directly visual ways to track the fate of genetic atoms using autoradiography. J. Herbert Taylor and colleagues analyzed radiolabeled chromosomes in metaphase of Vicia faba (English broad bean) using autoradiographs, and found the two daughter chromosomes of a labeled parent to appear ‘equally and uniformly labeled’ (Taylor et al., 1957, p. 127). Meselson and Stahl cited this experiment, which in turn referenced Levinthal’s autoradiographs of 32P-labeled phage. In 1961, John Cairns used autoradiography of tritium-labeled T2 DNA to determine the size of the genetic nucleic acid (Cairns, 1961). Unlike earlier studies (such as Levinthal’s) Cairns found a single large DNA molecule of molecular weight over one hundred million daltons. He also showed that suicide from 3H-decay was similar to that for 32P-decay. Tritium labeling offered more resolution on autoradiographic emulsions than phoshorus-32, because the electrons released from 3H-decay traveled less than one micron. Cairns extended his autoradiographic technique to probe the mechanism of replication. As he put it, ‘it seemed probable that, with more care, the chromosome could be isolated intact and, caught in the act of replication, its DNA be displayed by autoradiography’ (Cairns, 1963, p. 208). If one goal since Delbrück and Luria’s initial collaboration in 1942 was to catch a microbe in the act of reproducing, Cairns finally succeeded. But just as importantly, he furthered the use of radiolabels in combination with autoradiography to make chromosomes and their constituent genes visible.

The myriad efforts of phage researchers to use suicide experiments and other radiological techniques to understand viral genetics produced an increasingly arcane scientific literature (much of it now dimly remembered). As Stahl explained by way of a caveat at the beginning of a 1959 review entitled ‘Radiobiology of Bacteriophage’:

At times it may appear that the reviewer has forgotten that the primary aim in employing radiation in the study of phage is to elucidate the normal state of affairs. However, almost all experiments involving the irradiation of phage have raised far more questions than they have answered. This has resulted in the situation that there now exists, a ‘radiobiology of bacteriophage’, a collection of observations and hypotheses arising from irradiation experiments, leading no one knows where, but selfishly demanding an explanation. (Stahl, 1959, p. 354)

Phage researchers, expecting radioisotopes to illuminate the molecular process of gene replication, instead were led on to unanticipated and complex questions about the biological effects of radiation, problems they seemed unwilling to abandon so long as the next experiment beckoned. One cannot help but wonder whether the fallout debates of the mid-to-late 1950s gave these ‘suicide experiments’ a wry resonance with the cultural anxieties that permeated the nuclear age.

5. Concluding reflections

The importance of target theory to the genesis of molecular biology is widely cited, but rarely scrutinized.59 This trajectory of work on phosphorus-32 labeling and suicide experiments provides a window on the continuing legacy of radiobiology within molecular biology during the 1950s. Phage experiments exploited two features of 32P-labeled DNA: the isotope was used to trace the transfer of labeled atoms from one generation of phage to another, and the susceptibility of phage to killing by decay inactivation was a tool for examining recombination, reactivation and replication. In doing so, researchers integrated the more biochemical practices of isotopic tracing with radiation genetics. These investigations failed to shed as much light on gene replication as hoped, despite years of effort and elegant experiments by members of the phage group. Radiolabeled phage did not exhibit a sufficiently stable linkage between material and genetic transfer to illuminate the molecular mechanisms of replication and recombination, urgent questions of the day. Rather, the dynamic aspects of genetic exchange in phage generated problems that occupied a generation of molecular biologists.

The perceived futility of suicide experiments calls into question the triumphalist way phage genetics is portrayed in popular accounts of molecular biology, and complicates the entrenched historiography of how physicists, particularly acolytes of Max Delbrück, revolutionized biological knowledge.60 Radiobiology was a magnet for such physical scientists who entered phage research in the late 1940s and 1950s, including Stent, Levinthal, and Benzer. And yet this line of investigation is scarcely mentioned in the canonical histories of molecular biology, both older tomes by Robert Olby and Horace Freeland Judson and also more recent synoptic accounts such as Harrison Echol’s Operators and promoters (Olby, 1994 [1974]; Judson, 1979; Echols, 2001).61 Although neglected in historical accounts, phosphorus transfer and suicide experiments in fact connected two benchmarks of molecular biology: the eponymous Hershey–Chase experiment in 1952 and the Meselson–Stahl experiment six years later. For Stent and Levinthal, their ongoing phage experiments with phosphorus-32 were aimed at resolving how DNA was duplicated, and how the genetic material was partitioned through replication, issues which remained highly uncertain through much of 1950s. Following the use of radioisotopes in this set of investigations turns up a different—and more meandering—trajectory for molecular biology in the 1950s, even if one stays within the research trails of the phage group.

Even if suicide experiments did not elucidate gene replication in ways that some phage researchers hoped, the habit of tagging DNA with phosphorus-32—and detecting the label visually on photographic film—took on a momentum of its own. Only a few steps of this technological genealogy have been recovered here, but these strategies of visualization subsequently became crucial to hybridization technologies such as Southern blots and underlay the routine detection of DNA fragments on polyacrylamide gels, particularly those resulting from sequencing reactions. The practice of labeling nucleic acids with radioactive tags enabled scientists to follow genetic units not only in time but also in space. As Guido Pontecorvo stated presciently in 1952, ‘Biochemistry is clearly in need of something which will permit it to pass from the study of time-sequences of reactions to sequences organized in space as well as in time. The chromosome as an integrated pattern of active points may offer a grip’ (Pontecorvo, 1952, p. 145). Radioisotopes proved exquisitely suited for visualizing nucleic acids in space, first chromosomes and, later, DNA and RNA sequences. In this respect, the consequences of suicide and transfer experiments had less to do with resolving the nature of the gene than with reinforcing ways of making genetic molecules visible. The availability of isotopes as peaceful ‘dividends’ of atomic energy crucially supported this technological trajectory; whereas the first experiments labeling phage with phosphorus-32 relied on the existence of cyclotrons at Washington University, the University of Chicago, and Copenhagen, by the late 1940s virus researchers could obtain a wide variety of biologically useful radioisotopes directly and cheaply from the US government’s reactor at Oak Ridge.

Viewed more broadly, molecular biologists were hardly the only postwar researchers to exploit newly available radioisotopes in their efforts to illuminate key molecules and their chemical transformations. The use of phosphorus-32 in suicide and transfer experiments with phage mirrored the dual use of this isotope in other fields, particularly in medicine, where this isotope similarly served as both a radiation source and a tracer. Phosphorus-32 was widely used as a therapeutic agent for polycythemia vera, a disorder characterized by the overproduction of red blood cells. Here phosphorus-32 served to irradiate tissue; the beta rays given off by this isotope, localized in the bone marrow, attenuated blood cell formation.62 Clinicians also used phosphorus-32 in diagnosing tumors, which tend to concentrate the isotope eight- to one-hundred-fold due to the high rate of turnover of phosphate in rapidly growing cells (United States Atomic Energy Commission, 1955, p. 22). Medical diagnosis with isotopes, which ultimately proved more successful than therapy, was essentially an application of tracer methodology, in which a radioisotope served as a way to visualize altered function or growth in a particular tissue or organ. Radioactive isotopes brought into view key biological molecules, revealing their dynamic movement and chemical transformations. In terms of the emphasis on visualization, diagnostic radioisotopes built upon the tradition of X-rays while moving the source of radiation from without the body to within it.63

Tracer uses of phosphorus-32 extended widely beyond medical diagnostics, being an isotope of choice in biochemical experiments in animals, plants, and bacteria—as well as ecological research. Right after the war, G. Evelyn Hutchinson began to use phosphorus-32 from the Yale cyclotron to trace the cycling of phosphorus through the phytoplankton and inorganic matter of Linsley Pond in Connecticut. He soon began receiving radiophosphorus of higher specific activity from Oak Ridge, which enabled a more quantitative study.64 This built on an analogy Hutchinson offered in 1940. Reviewing a book by Frederick Clements, he stated: ‘If, as is insisted, the community is an organism, it should be possible to study the metabolism of that organism’ (Hutchinson, 1940, p. 268). There are strong epistemic commonalities between tracer methodology in biochemistry and in ecology—radioisotopes helped give ‘ecosystem’ a concrete meaning, as well as elucidating intracellular metabolic pathways from photosynthesis to glycolysis (Creager, 2006).

Consider what a more complete historiography of molecular biology in terms of materials and instruments would look like—a historiography from the bench up, so to speak. During the past decade, the literature on experimentation in molecular biology has revealed intriguing gaps between the trajectory of the technologies and tools key to molecular biology and a disciplinary history as such. To take one example, the development of high-speed ultracentrifuges made a host of subcellular agents apprehensible, both conceptually and materially. Hans-Jörg Rheinberger and Jean-Paul Gaudillière have shown in rich detail how this technology mattered for key developments in molecular biology (Rheinberger, 1997; Gaudillière, 2002).65 Yet a history of centrifugation would turn up a much wider range of activities and groups that those conventionally associated with molecular biology—there would be cancer researchers of various stripes, colloidal chemists, some renegade physicists, vaccine developers, cell biologists, to name just a few. Radioisotopes reveal the same pattern—they may have been ‘sine qua non’ in molecular biology, yet a history of radioisotope usage illuminates a much wider range of developments in life science research than those associated with molecular biology. In fact, the diffusion of radioisotopes was—if anything—even wider than that of the black-boxed instruments associated with molecular biology, even as they were used in conjunction with these machines to bring molecular agents into view. Accordingly, to take seriously the history of experimentation is also to call into question the field of molecular biology as a clearly bounded enterprise. Indeed, as scientists and scholars now contemplate the historical dissolution of molecular biology, I would caution us not to romanticize its more ‘solid’ existence as a postwar discipline—like its radioactive tracers, molecular biology has always had a flickering, changeable character.

Acknowledgements

Work on this project was supported by the author’s NSF CAREER Award SBE 98-75012, 1999–2006; NEH Fellowship Award, 2006–2007; and NIH National Library of Medicine Grant, 2007–2010. For their comments and suggestions I thank Richard Calendar, Soraya de Chadarevian, Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Bruno Strasser, and the participants of the workshop on the History and Epistemology of Molecular Biology held in Berlin, 13–15 October 2005. I gratefully acknowledge the Bancroft Library for permission to quote from the Gunther S. Stent papers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

A note on terminology: in 1947, Truman Kohman (1947), p. 356, noted that isotope by definition ‘refers to a species of a particular or designated element, and emphasizes its relationship to other isotopes of that element’. For this reason he introduced ‘nuclide’, or radionuclide, to refer to a species of atom, arguing that it was preferable to the ‘radioisotope’. However, for historical accuracy this essay follows original sources in using the term radioisotope; the term radionuclide was not commonly used in the late 1940s and even 1950s and still is not used uniformly. In referring to specific radionuclides, I will spell out the element, such as phosphorus-32, except when it is part of a prefix, for example, 32P-labeled-bacteriophage. Many researchers in the 1950s used the subscript after the letter designating the chemical element: P32, as is evident in quoted passages.

United States Atomic Energy Commission (1955), p. 2. Because many shipments were bulk amounts going to companies that prepared specialized radiolabeled molecules and other reagents, this number underestimates the actual number of shipments received at end destinations. As stated on the same page, ‘The total number of isotope shipments received by ultimate users is several times greater than the quoted number of shipments [63,990] from ORNL [Oak Ridge National Laboratory]’.

In addition to the other citations in this paragraph, see Hagen (1992), Ch. 6; Bocking (1997); Rainger (2004); Gaudillière (2006); Santesmases (2006).

On common simplifications of the Hershey–Chase experiment in popular and pedagogical representation, see Wyatt (1974).

On the notion that genes are composed of protein, see Olby (1994); Kay (1993), ‘Protein paradigm’, pp. 104–120. On genes as nucleoproteins, see Creager (2002), Ch. 6.

Hershey & Chase’s experiment was not the first to suggest that genes were composed of DNA (that of Avery, MacLeod and McCarty came eight years earlier), but it is the generally the one credited with persuading biologists; see Stent (1971), p. 315; Judson (1979), pp. 130–131; Echols (2001), pp. 12–13.

See Elzen (1986); Kay (1988); Zallen (1992); Rasmussen (1997a); Gaudillière & Löwy (1998); and Rheinberger (2001).

On the role of the Rockefeller Foundation in the development of new instrumentation, Kohler (1991); on material epistemology, Rheinberger (1997); Pickering (1995); Baird (2004).

For example, see United States Atomic Energy Commission (1948), p. 5. This analysis is adapted from Creager (2006), pp. 653–654, where I offer fuller explanation.

The Meselson–Stahl experiment used a heavy isotope of nitrogen, not a radioactive isotope. The AEC’s isotope distribution program included heavy isotopes, but they were not in as much demand as radioisotopes by biomedical researchers. On the Meselson–Stahl experiment, see Holmes (2001).

Stent (1963), p. 277; he cites Appelmans (1922) and Gildemeister (1923).

Target theory, as put forth by James Crowther in 1924, offered a statistical approach to analysing the effects of radiation on organisms or their constituents. See Crowther (1924); Lea (1947); Summers (2002); Yi (2007); the essays in Sloan & Fogel (Under review).

Hayes (1964), p. 457; Brock (1990), pp. 118–119. For an example of this type of experiment, see Pollard & Forro (1949).

Moreover, biological inactivation was not a generic response to radiation but varied according to the source. For example, inactivation by ultraviolet radiation depended on the absorption spectra, whereas intracellular inactivation with isotopes, such as phosphorus-32, depended on chemical properties of the isotope—which would cause its incorporate into biological molecules—as well as the kind of energy released upon radioactive decay. Much of the radiobiology literature aimed at differentiating these effects.

As Luria makes clear in a footnote (1955, p. 333), the review was written in 1951 and not updated before publication.

Kamen and Gest initially worked with phosphorus-32 from batches they prepared in the Washington University cyclotron for ‘use by Institute of Radiology clinicians in treating certain blood diseases’ (Gest, 2002, p. 334).

Kamen had also worked for the Manhattan Project under E. O. Lawrence at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory. Prior to World War II he prepared cyclotron-generated radioisotopes for research and clinical use, while also involved in research with isotopes as tracers. Beginning in 1939, Kamen collaborated with Sam Ruben and H. A. Barker using carbon-11 to study photosynthesis; they traced carbon fixation in plants and other organisms. He and Ruben subsequently discovered carbon-14 in 1940. Kamen was dismissed from the Rad Lab by the US Army in 1944 on account of security concerns; he went to Washington University the next year where he continued photosynthesis research using radioisotopes. Gest (2002); Kamen (1963); Kamen (1985).

‘Reproduction is perhaps the most basic and characteristic feature of life. From the chemical point of view it is also the most obscure feature: atoms do not reproduce. When a living organism reproduces, there are now two atoms in the system for each one of the parent system. These additional atoms, of course, have not been “generated” by reproduction of the parent’s atoms, but have been assimilated from the environment. Although the two progeny organisms may be biologically identical we should consider that their atoms can be classified into two classes: parental atoms and assimilated atoms. How are these atoms distributed between the two progeny organisms? Is one of the progeny all parental, the other all assimilated, or each half and half? Or perhaps both assimilated and the parental atoms dissimilated and passed into the environment? Are there specific macromolecular structures (genes?) that are preserved and passed on intact to the progeny? To answer questions of this kind we must be able to distinguish between parental and assimilated atoms and, in principle, this can be accomplished by the use of tracers’ (Maaløe & Watson, 1951, p. 507).

Alfred D. Hershey, Research Report 1950–1951, Department of Genetics, Carnegie Institution of Washington, reprinted in Stahl (2000), pp. 171–178, on p. 175.

Chase is one of those figures in the history of molecular biology who is virtually unknown except for the eponymous experiment—otherwise, she is one of the field’s ‘invisible technicians’, to use Steven Shapin’s phrase (Shapin, 1989). Hershey did value her contributions highly, telling Bruce Wallace that only she ‘had the concentration needed to carry out the protocol that led to the Hershey–Chase experiment’ (Stahl, 2000, p. 99). She moved from Cold Spring Harbor to work with A. H. Doermann at University of Rochester.

Putnam and Kozloff had also attempted experiments looking at the transfer in bacteriophage of both labeled protein and labeled nucleic acid to progeny, using phosphorus-32 to label DNA and the heavy isotope nitrogen-15 to label protein, but they achieved only low (10%) levels of transfer in protein and nucleic acid (Putnam & Kozloff, 1950).

In addition, this 35% transfer rate was seen in both the first and second cycles of growth. According to Hershey, ‘This means that neither phosphorus nor sulfur is transferred from parent to progeny in the form of special hereditary parts of the phage particles’ (Hershey, Roesel et al., 1951). The experiment with Chase overturned this interpretation.

On the experiment with Chase as reinvestigating the issue, see Hershey (1953), p. 102.

As Hershey and Chase understatedly put it, ‘We infer that sulfur-containing protein has no function in phage multiplication, and that DNA has some function’ (Hershey & Chase, 1952, p. 54).

On Hershey’s expectations, see Szybalski (2000), p. 19. On reasons for lack of interest in phage DNA, see Hershey (1966).

The correspondence cited here attests to the vitality of an ‘in-group’ of phage researchers closely affiliated with Delbrück, Luria, and Hershey, the three who are conventionally credited with paternity rights for the ‘phage group’. At the same time, my focus on radiolabeling experiments exposes a wider circle of participants, including those either not part of the clique or more marginal (such as Seymour Cohen and Lloyd Kozloff). On the importance of fetschrifts to the consolidation of collective identity and scientific genealogies, see Abir-Am (1985). Stent was central to such efforts on behalf of the phage group.

In this connection, see Summers (1995); Holmes (2006).

Multiplicity reactivation refers to Salvador Luria’s observation that two or more UV-inactivated phage particles, if they infect the same bacterium, can cooperate or combine to productive viable progeny. Crossreactivation is also called marker rescue; it occurs in mixed infection when a genetic marker of an inactive irradiated bacteriophage appears in the progeny when crossed with active phage. Renato Dulbecco discovered photoreactivation in 1950 when he observed that UV-inactivated phage could be reactivated through illumination by a visible light source. Luria (1947); Dulbecco (1950); Luria (1952); for general explication, Stent (1963), especially pp. 282–289.

For examples see Lindee (1994); de Chadarevian (2006); Rader (2006).

Seymour Benzer exemplifies this trend and cited Pontecorvo’s paper; see Holmes (2006).

To use the language of phage biology, the Luria–Latarjet experiment examined the radiosensitivity of vegetative phage ‘at various stages of the latent period’ (Stent, 1963, p. 300). The period after phage infects bacteria, when infective particles cannot be recovered, is called the ‘dark’ or eclipse period.

Gunther Siegmund Stent, ‘Fellowship Summary, August 1950–July 1951, Radioactive Phosphorus Tracer Studies on the Reproduction of T4 Bacteriophage’, submitted with letter to Charles E. Richards, National Research Council, 16 August 1951, Gunther S. Stent papers, BANC 99/149z, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, [hereafter simply Stent papers], box 1, Folder American Cancer Society.

Specifically, infection with one bacteriophage (γ, later called T2) prevented the bacteria from producing another (α, later called T1), a phenomenon termed ‘interference’. Subsequent studies enabled them to different ‘mutual exclusion’ (in which a single bacterium would only produce one type of virus at a time) from the ‘depressor effect’, which referred to the observation that a bacterium infected with more than one phage produced less of the prevailing phage than it would otherwise. My point is that, while interesting, these findings did not advance the understanding of virus reproduction, to the evident frustration of Delbrück. As he asserted in his Harvey Lecture (Delbrück 1946, p. 162): ‘Remember that what we are out to study is the multiplication process proper, we want to get to the bottom of what goes on when more virus particles are produced upon the introduction of one virus particle into a bacterial cell. All our work has circled around this central problem’.

Gunther S. Stent to Evelyn Witkin, 2 December 1952, Stent papers, box 16, folder Witkin, Evelyn.

See letters from 1952–1955 in Stent papers, box 1, folder Atomic Energy Research Establishment; box 7, folder Isotopes; and box 11, folder Oak Ridge. Stent also explored procuring the radiophosphorus from the Canadian atomic energy installation at Chalk River. Only in 1951 did the US AEC complete arrangements to allow researchers in the US to import radionuclides from the UK. See AEC 231/16 in Secretary General Papers of the AEC, National Archives-College Park, RG 326, E67A, box 47, folder 1, Foreign Distribution of Radioisotopes, Vol. 3. On the British radionuclide supply, see Kraft (2006).

Cyrus Levinthal to Gunther S. Stent, 17 November, 1952, Stent papers, box 9, folder Levinthal, Cyrus.

Gunther S. Stent to A. H. Doermann, 19 February 1953, Stent papers, box 4, folder Doermann, A. H. A few months later, along similar lines, Stent wrote, ‘I have made a wedding of the Luria–Latarjet experiment with Hershey, Kamen, Kennedy and Gest suicide, i.e., I infected bacteria with highly radioactive T2 and T3, permitted phage development to take place for various lengths of times, and then froze the systems’. Gunther S. Stent to S. E. Luria, 9 April 1953, Stent papers, box 10, folder Luria, Salvador #2.

On timing, see Stent (1955), p. 855.

Gunther S. Stent to A. H. Doermann, 25 August 1953, Stent papers, box 4, folder Doermann, A. H.

A. H. Doermann to Gunther S. Stent, 28 August 1953, Stent papers, box 4, folder Doermann, A. H. Doermann commented also that ‘our interpretations may perhaps be at variance’, but Stent soon abandoned the interpretation Doermann took issue with—that the inactivation of one marker stabilized another marker. See Gunther S. Stent to A. H. Doermann, 10 September 1953, Stent papers, box 4, folder Doermann, A. H. Doerrman moved in the fall of 1953 from Oak Ridge to Rochester; on the results from his group, see Doermann, Chase, and Stahl (1955).

Gunther S. Stent to Cyrus Levinthal, 14 September 1953, Stent papers, box 9, folder Levinthal, Cyrus.