Abstract

Insect pests are the major cause of damage to commercially important agricultural crops. The continuous application of synthetic pesticides resulted in severe insect resistance by plants. This causes irreversible damage to the environment. Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) emerged as a valuable biological alternative in pest control. However, insect resistance against Bt has been reported in many cases. Insects develop resistance to insecticides through mechanisms that reduce the binding of toxins to gut receptors. Nonetheless, the molecular mechanism of insect resistance is not fully understood. Therefore, it is important to study the mechanism of toxin resistance by analyzing amino‐peptidase‐N (APN) receptor of the insect M. sexta. A homology model of APN was constructed using Insight II molecular modeling software and the model was further evaluated using the PROCHECK program. Oligosaccharides participating in post translational modification were constructed and docked onto specific APN functional sites. Post analyses of the APN model provide insights on the functional properties of APN towards the understanding of receptor and toxin interactions. We also discuss the predicted binding sites for ligands, metals and Bt toxins in M. sexta APN receptor. These data help in the development of a roadmap for the design and synthesis of novel insect resistant Cry toxins.

Keywords: glycosylation, Manduca Sexta, post transnational modifications, aminopeptidase-N, Cry toxins

Background

Gram positive bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is an environmentally safe biopesticide used against insects. It produces crystalline inclusions during the sporulation phase of its life cycle [1]. These Cry toxins are environmental friendly and provide protection against a wide range of insects like beetles, caterpillars, mosquito larvae etc. Pore formation takes place on the insect midgut brush border membrane after the receptor binds to the toxin. This leads to an osmotic imbalance for insect mortality [2]. Bt toxins binds with four different kinds of insect receptors through oligomerization [3]. The receptors include aminopeptidaseN (APN), cadherins, glycoproteins and alkaline phosphatase [4]. The APN receptor plays a major role with Cry toxin interactions. APN is a membrane protein and it undergoes post translational modifications (PTMs) through N and Oglycosylation process. N or O glycosylation is a post translational event that has implications on protein structure, stability, molecular recognition and signaling activities [5]. M. sexta aminopeptidaseN receptor attached to the midgut membrane with glycosyl phosphotidyl inositol (GPI) have anchoring function [4]. Moreover, mass spectrometric studies of the oligosaccharides were found to be Fuc2Hex3HexNAc3, Hex3HexNAc2, Fuc4Hex3HexNAc4 and Fuc3Hex3HexNAc3. These site specific oligosaccharides attached to different sites of APN are 295-297, 609-611, 623-625 and 752-754, respectively [6]. The cadherin receptor toxin binding sites were identified by using phage display technique [7]. However, no such reports in APN receptor. Therefore, it is of interest to predict potential interaction sites with various ligands and peptides to understand receptortoxin molecular interactions.

Methodology

Sequence

The APN protein sequence of length 990 amino acid was retrieved from Swiss Prot (ID-Q11001).

Template structure

We used the template structure of Tricorn interacting factor from Thermoplasma acidophilum (PDB ID: 1ZIW) for modeling the APN protein.

Model refinement and evaluation

The APN protein model was constructed by using Insight II (Accerlarys) molecular modeller program and the structure is minimized by applying consistence valance force field (CVFF). Subsequent minimization was done using steepest descent and conjugated gradient algorithms in discovery program. The predicted 3-D structure was evaluated using the PROCHECK program.

Structural and topological studies

Detailed domain topologies of APN was predicted individually by using the TOPS program [9] and number of sheets and helices in the domains were counted by using the PROF program [10]. Oligosaccharides binding motifs of APN were predicted by using NetOGlyc and NetNGlyc programs from ExPasy site [8].

Oligosaccharides 3D structure prediction

2D Oligosaccharide structures were collected from experimental data provided elsewhere [6] and their 3D structures were constructed by using Chemultra and Chemsketch softwares. Moreover, file conversion was carried out using the OPEN BABLE software. Nevertheless, the above said structures, molecular weights and formulae were predicted with the help of ligand scout program and 3D models were minimized by using the TINKKER software [11, 12]. The best conformational structures were selected on the basis of minimum energies.

Oligosaccharide docking and refinements

Specific Oligosaccharide molecules were docked on experimentally predetermined sites of APN. Docking was carried out using DOCK software version 6.0 and by applying AMBER force fields [13]. Oligosaccharides were docked one at a time to APN and the docking binding energies were calculated for four oligosaccharides.

Molecular interactions

The Ligplot tool was used to generate molecular level interactions [14]. Xscore program was used to select the best conformations among the docked complexes.

Multiple sequence alignment and active site prediction

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTALW to assess sequence conservation and polymorphism.

Active site identification

Interactive sites or motifs of APN were predicted using the POCKET program [16]. Active site analysis was performed using the ConSeq program which can identify the functional residues [15].

Solvent accessible surface area

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) is calculated using the POPS program.

Discussion

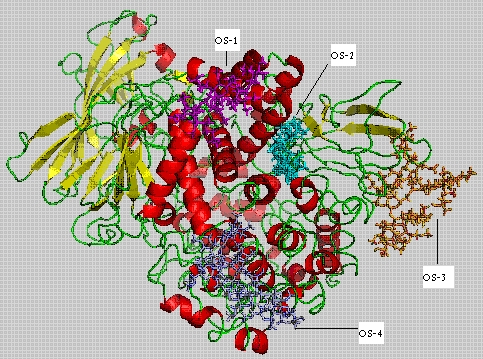

Figure 1 shows four predicted domains. DomainI is located at the Nterminal region and it was found that domain I (1193 amino acids) consists of an alpha helix and nine beta strands. DomainII (194443) consists of eight alpha helices, eleven beta strands and it has also been recognized as a catalytic domain. DomainIII (443560) consists of four alpha helices and four beta strands. DomainIV is located at the Cterminal region (565-995) consisting of nineteen alpha helices and seven beta strands. Experimental results show that oligosaccharides binding sites are located at various positions 295-297, 609-611, 623-625 and 752-754 [6].

Figure 1.

APN receptor 3D-model showing four docked oligosaccharides on their respective binding sites

Oligosaccharides 2D structures were converted into 3D structures and four potential oligosaccharides were docked to APN receptor at specific locations to develop glycoprotein models (Table 1). Oligosaccharide molecules are having different molecular weights. OS-1, OS-3 and OS-4 are fucosylated molecules, where as OS-2 is the only nonfucosylated molecule. Fuc2Hex3HexNAc3 is an oligosaccharide (OS-1) having molecular weight of 1563.76 with seven ringed structure. Hex3HexNAc2 is of (OS-2) five ringed structure with molecular weight of 1183.35. Fuc4Hex3HexNAc4 an eleven ringed structure (OS-3) and its molecular weight is 2334.77. The last oligosaccharide Fuc3Hex3HexNAc3 (OS-4) is a nine ringed structure with molecular weight of 2027.31.

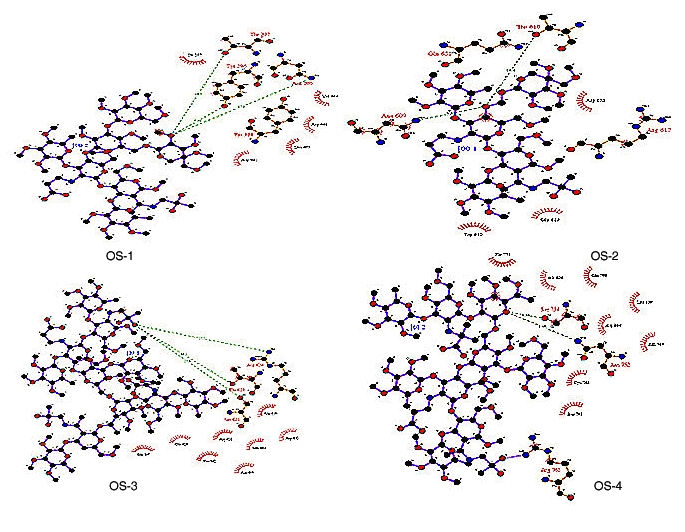

The single oxygen atom of oligosaccharide OS-1 formed three hydrogen bonds with different residues of APN 295 N, 296 Y and 297 T with hydrogen bond lengths 17.3, 7.24 and 14.7, respectively and binding energy of 24976.2 Kcal/J. The insect motif 609NTT611 is highly conserved and it is commonly utilized for glycosylation [17]. When OS-2 is successfully docked on to 609NTT611 of APN, the single oxygen atom in it formed two hydrogen bonds with Asp609 and Thr610 of APN with bond lengths of 5.9 and 10.4, respectively. The final minimized structure of APNOS-2 docked complex has a binding energy of 24770.6 Kcal/J.

The OS-3 is docked on to 623NRT625 motif of APN. The oxygen atom in OS-3 formed three hydrogen bonds with different residues (Ser621, Arg624 and Thr625) of APN like with bond lengths of 17.9, 17.7 and 16.1 respectively. The final docked complex of APN-OS-3 has a binding energy of 24026.9 Kcal/J. OS-4 was docked to 751NGS753 motif of APN and the oxygen atom formed two hydrogen bonds with different residues of APN Ser754 and 752Asp 752 with bond lengths of 4.54 and 8.46, respectively (Figure 2). The docked complex of APN-OS-4 has a binding energy of 251617 Kcal/J.

Figure 2.

Molecular interactions between APN receptor and oligosaccharides (OS-1, OS-2, OS-3 & OS-4) is shown. The diagram is illustrated using LIGPLOT

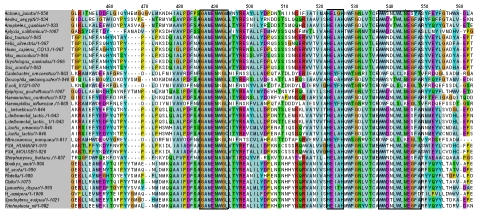

Multiple sequence alignments of APN sequences from various organisms showed three highly conserved motifs (Figure 3). The three conserved regions are GEMENWGL (bestatin binding site in E. coli [18]), HEXXH (Zinc binding site [19]) and WWDNLWLNEGFA (associated with tumor angiogenesis in human [20]). The solvent accessibility data of these conserved regions in the predicted model is given Table 2. The solvent exposed residues in the conserved regions are visualized using solvent accessible surface area data. Thus, the data presented here help in the development of a roadmap for the design and synthesis of novel insect resistant Cry toxins.

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of different APN protein sequences showing three highly conserved regions (highlighted in boxes)

Conclusion

A homology model of APN was constructed using Insight II molecular modeling software and the model was further evaluated using the PROCHECK program. Oligosaccharides participating in post translational modification were constructed and docked onto specific APN functional sites. Post analyses of the APN model provide insights on the functional properties of APN towards the understanding of receptor and toxin interactions. We also discussed the predicted binding sites for ligands, metals and Bt toxins in M. sexta APN receptor. These data help in the development of a framework for the design and synthesis of novel insect resistant Cry toxins.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dr. M. D. Tiwari, Director, IIIT, for encouragement and infrastructural support.

Footnotes

Citation:Singh & Sivaprasad, Bioinformation 3(8): 321-325 (2009)

References

- 1.Gill SS, et al. Ann Rev Entomol. 1992;37:615. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bravo A, et al. Elsevier B V. 2005;175 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez A, et al. FEBS Le. 2002;513:242. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight P, et al. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peter K, et al. Science direc. 2004;34:101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephans E, et al. European Journal Biochem. 2004;271:4241. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo S, et al. Insect Biochem Mol Bio. 1997;27:735. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. http://ca.expasy.org/

- 9. http://www.tops.leeds.ac.uk/

- 10. http://www.aber.ac.uk/~phiwww/prof/

- 11. http://www.inteligand.com/ligandscout/download.shtml.

- 12. http://dasher.wustl.edu/tinker/

- 13.Glaser F, et al. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:163. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/bsm/ligplot/ligplot.html.

- 15. http://conseq.tau.ac.il/

- 16.Levitt DG, Banaszak LJ. J Mol Graphics. 1992;10:229. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(92)80074-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altmann F, et al. Glycoconj J. 1999;16:109. doi: 10.1023/a:1026488408951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiyoshi The Jour Bio Chem. 2006;281:33664. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandu D, et al. J Bio Chem. 2003;278:5548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasqualini R, et al. The J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1189. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.