Abstract

Giving coding region structural features a role in the hypomethylation of specific genes, the occurrence of G+C content, CpG islands, repeat and retrotransposable elements in demethylated genes related to cancer has been evaluated. A comparative analysis among different cancer types has also been performed. In this work, the inter-cancer coding region features comparative analysis carried out, show insights into what structural trends/patterns are present in the studied cancers.

Keywords: epigenetics, cancer, CpG islands, hypomethylation

Background

Alterations of DNA methylation have been recognized as an important component of cancer development [1]. Hypomethylation generally arises earlier and is linked to chromosomal instability and loss of imprinting [2–6], whereas hypermethylation is associated with promoters and can arise secondary to gene silencing [7–9], but might be a target for epigenetic therapy [10]. It is not currently known why certain CpG islands are hypermethylated or hyphometylated in specific cancers but not in others [1]. Some of these events have been observed in vitro and using in vivo animal models [2–4,11,12] but their relative importance in human disease is not understood. Recent studies suggest that some methylation patterns are discernible in risk groups and certain diseases. Indications are that the hypomethylation of specific DNA repeat elements or genes can be disease-specific [13]. These repeat sequences may be transposable elements found interspersed throughout the genome, or large repeat sequences and simple repeat ones, such as DNA satellites, that are found commonly in heterochromatin.

Hypomethylation of satellites and retroelements together should account for the greater part of the decrease in methyl-cytosine content in cancer cells. Decreased methylation of single-copy genes does not contribute significantly to the decrease in quantity, but whether hypomethylation may lead to the reactivation of genes silenced in normal cells is an important issue. The site reported to be hypomethylated in several human cancers is located within the coding region. It may become demethylated in cancers as a consequence of global hypomethylation or may reflect increased transcriptional activity [14,15,16]. The relationship between hypomethylation of specific genes and repeat elements within the genome may serve as useful diagnostic indicators for disease [13]. Nowadays, more information is required with regard to what repeat elements are specific to what diseases and whether this information can be used to predict disease onset or progression. Thus, the occurrence of G+C content, CpG islands, repeat and retrotransposable elements in demethylated genes related to cancer has been evaluated in this work. Moreover, a comparative analysis among different cancer types has also been performed in order to elucidate what structural trends/patterns are present in the studied cancers.

Methodology

All selected genes were compiled from the recent literature (see Table 1 in supplementary material) and were collected from the NCBI nucleotide database [21]. The sequence characteristics of the coding regions of each gene were examined in the analysis. For CpG dinucleotide analysis, we used the NEWCPGREPORT program [17], and the total number of CpG islands was counted. For the repeat element analysis, the Repeat Masker program [18] was used and for tandem repeat analysis, the ETANDEM program [19] was used. All classes of repeat elements output from Repeat-Masker were collected. We used ETANDEM to obtain numbers of tandem repeat elements ranging from 5 bp to 100 bp. All the statistical calculations were performed using the Minitab software [20].

Discussion

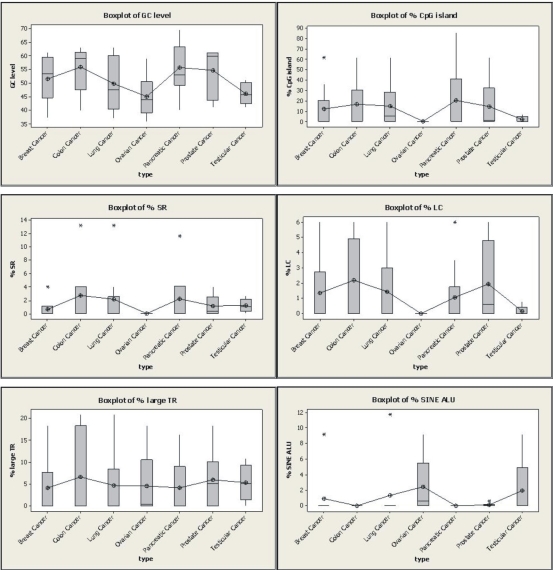

Firstly, a list of genes that are demethylated in cancer according to the recent existing literature was compiled (Table 1 in supplementary material). We observed that these genes are related with 7 different cancer types: breast, colon, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate and testicular. As it can be seen in Table 1, the ranges of genes affected by hypomethylation includes growth regulatory genes, enzymes, developmentally critical genes and tissue specific genes such as germ cell-specific tumour antigen genes, etc. Then, we selected 6 representative structural descriptors (variables) for the structural study: GC content, CpG islands, Simple Repeats (SR), Low Complexity (LC), Large Tandem Repeats (LTR) and SINE Alu. The [bp]% sequence characteristics of these descriptors were calculated for all gene coding regions. As it has stated before, the site reported to be hypomethylated in several human cancers is located within the coding region [13,15]. For this reason, the structural information related with this region could be very useful in order to develop a first stage approximation. Once the values for all the structural descriptors were calculated, we performed a distribution analysis of the [bp]% differences across all 7 cancer types. In order to evaluate tendencies, we also calculated the median and the average numbers for each descriptor and cancer types (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Boxplot graphs (median and interquartile) with the comparison of the different [bp] % seuence characteristic distributions across the different cancer types*. Note that the different average numbers are connected by a drawing line.

From the boxplot data comparisons in Figure 1, we observed how all the GC content, CpG islands, Simple Repeats (SR), Low Complexity Elements (LC) and Large Tandem Repeats (LTR) [bp] % average distributions follow the same trend in all the different cancers studied. In contrast, the SINE Alu [bp] % average distribution follows the opposite one. Apart form that, analyzing the value’s magnitude it can be observed that in general, the genes involved in the ovarian cancer show the smallest values for [bp] % and the largest value for the SINE Alu descriptor. On the other hand the major part of colon, pancreatic and prostate [bp] % values are the largest ones in all cases except for the SINE Alu descriptor (see Figure 1).

The relationship between CpG islands density and the GC content is logical taking into account that CpG islands are genomic regions that contain a high frequency of CG dinucleotides. Besides, the SR, LC and LTR elements follow the same CpG island trend while the SINE Alu follows the opposite one. To date, there seems to be very few comparative analyses of CpG islands density and their correlations with other genome features. Here, it seems clear that there is some structural mark/pattern that establishes a relationship among the different coding region features of the studied genes and so, a mark that relates different cancer types among them. After this preliminary approximation, we think that these observations would be related with different hypomethylation patterns observed in some specific cancers but not in others [1]. At this point, further investigation is required. Thus, we are studying the evolution of these trends in the sequences flanking the coding regions including the promoter sites. Our next objective will be the full identification of key structural characteristics that are unique to each cancer type. Moreover, a future detailed and extensive theoretical analysis of the methylation profiles of these sequences and their characteristics may reveal higher specificity and epigenetic signatures for cancer detection.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

This work has been financed by the project AGL2007-65678 of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology. We wish to thank Nuria Queralt Rosinach for her input, careful reading and comments of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jones PA, et al. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:415. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eden A, et al. Science. 2003;300:455. doi: 10.1126/science.1083557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaudet F, et al. Science. 2003;300:489. doi: 10.1126/science.1083558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm TM, et al. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:275. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui H, et al. Science. 2003;299:1753. doi: 10.1126/science.1080902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakatani T, et al. Science. 2005;307:1976. doi: 10.1126/science.1108080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark SJ, et al. Oncogene. 2002;21:5380. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stirzaker C, et al. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutskov V, et al. EMBO J. 2004;23:138. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egger G, et al. Nature. 2004;429:457. doi: 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5742. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karpf AR, et al. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8635. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann MJ, et al. Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;83:296. doi: 10.1139/o05-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz WA, et al. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrlich M, et al. Oncogene. 2002;21:5400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson AS, et al. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1775:138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. http://inn.weizmann.ac.il.

- 18. http://www.repeatmasker.org/cgibin/WEBRepeatMasker.

- 19. http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgibin/MobylePortal/portal.py?form=etandem.

- 20.Minitab Statistical Software Release 15.1. 2007. Minitab Inc., USA.

- 21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.