Abstract

Aims

Extending our earlier findings from a longitudinal cohort study, this study examines parents’ early and late smoking cessation as predictors of their young adult children’s smoking cessation.

Design

Parents’ early smoking cessation status was assessed when their children were age 8; parents’ late smoking cessation was assessed when their children were age 17. Young adult children’s smoking cessation, of at least 6 months duration, was assessed at age 28.

Setting

Forty Washington State school districts.

Participants and Measurements

Participants were 991 at least weekly smokers at age 17 whose parents were ever regular smokers and who also reported their smoking status at age 28. Questionnaire data were gathered on parents and their children (49% female and 91% Caucasian) in a longitudinal cohort (84% retention).

Findings

Among children who smoked daily at age 17, parents’ quitting early (i.e., by the time their children were age 8) was associated with a 1.7 times higher odds of these children quitting by age 28 as compared to those whose parents did not quit (OR = 1.70; 95% CI = 1.23, 2.36). Results were similar among children who smoked weekly at age 17 (OR = 1.91; 95% CI = 1.41, 2.58). There was a similar, but non-significant, pattern of results among those whose parents quit late.

Conclusions

Supporting our earlier findings, results suggest that parents’ early smoking cessation has a long term influence on their adult children’s smoking cessation. Parents who smoke should be encouraged to quit when their children are young.

Keywords: parent smoking cessation, young adult smoking cessation

The prevalence of smoking among young adults in the United States has not changed significantly since 2004 [1], suggesting a stall in the previous 7-year (1997--2004) decline in cigarette smoking among US adults. Currently, adults aged 18 to 28 have the highest rate of smoking of any age groups [2]. Young adult smoking has ominous public health implications [3, 4]: an increased likelihood of a lifetime of smoking, thereby contributing to the approximately 440,000 premature deaths annually attributed to smoking and the approximately $157 billion in annual health-related economic losses in the U.S. alone [5].

A substantial number of young adults quit smoking by the time they are older. Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project (HSPP) cohort data show that of all daily smokers at age 17, 24% had quit smoking for at least six months by age 28 [6]. This level of cessation may reflect the fact that by age 28, nearly all individuals have passed through emerging adulthood [7, 8] —a period of identity development that can present psychosocial and lifestyle changes (e.g., social drinking) found to be predictive of smoking [9]. Instead, by age 28 many individuals have entered important social roles (e.g., marriage) known to predict smoking cessation [10]. Given the serious public health importance of smoking during young adulthood and the encouraging amount of smoking cessation occurring by age 28, using the HSPP cohort data to learn about predictors of young adult smoking cessation could lead to the development of future smoking cessation interventions.

One predictor of young adult smoking cessation which has been studied in recent years is parents’ smoking cessation [11, 12]. Specifically, using HSPP data, the first study on this topic reported that children of parents who quit smoking early (i.e., by the time their children were age 8) had an increased odds of quitting smoking for at least one month by age 19 as compared to children of parents who did not quit early. There was no association between parents quitting late (i.e., parents who smoked when their children were age 8 but quit by the time they were age 17) and their children quitting by age 19 [11]. The second study on this topic showed no prospective association between parents’ smoking cessation by the time their children were age 9 and their young adult children’s quit attempts between ages 18–26 [12]. This study did not have enough young adults who quit smoking to use successful quitting as an outcome so quit attempts were instead the outcome. The confidence intervals in this study were wide, covering both null and substantial positive effects of parents’ quitting smoking on young adult cessation as well as overlapping with the confidence intervals of the Bricker et al. [11] results.

The primary purpose of the present study is to follow-up on the Bricker et al. [11] findings by examining the extent to which parents’ early and late smoking cessation predicts their young adult smoking children’s cessation by age 28—an age that reflects a developmentally significant period of life [7, 8]. The present study also addresses a key limitation of both the Bricker et al. [11] and McGee et al. [12] studies: the limited duration of young adult smoking cessation or quit attempts as an outcome. Specifically, the encouraging 24% of age 17 smokers who had quit smoking for at least six months by age 28 provides higher statistical power for using successful quitting (i.e., at least 6 months) as an outcome.

In sum, in this follow-up study we test whether parents’ early and late smoking cessation is associated with their adult children’s smoking cessation by at age 28, among children who were daily and weekly smokers at age 17.

Methods

Study Sample

The study sample came from the combined control and intervention cohorts of the HSPP, a large randomized school-based tobacco use prevention trial [13]. The HSPP was a group-randomized trial of school-based smoking prevention, whose study participants comprised two consecutive 3rd grade enrollments (i.e., age 8) in 40 school districts throughout Washington State [6]. The school districts were in small and medium-sized rural towns and cities, and suburban communities. Characteristics of these population-based control and experimental cohorts were very similar to each other [13].

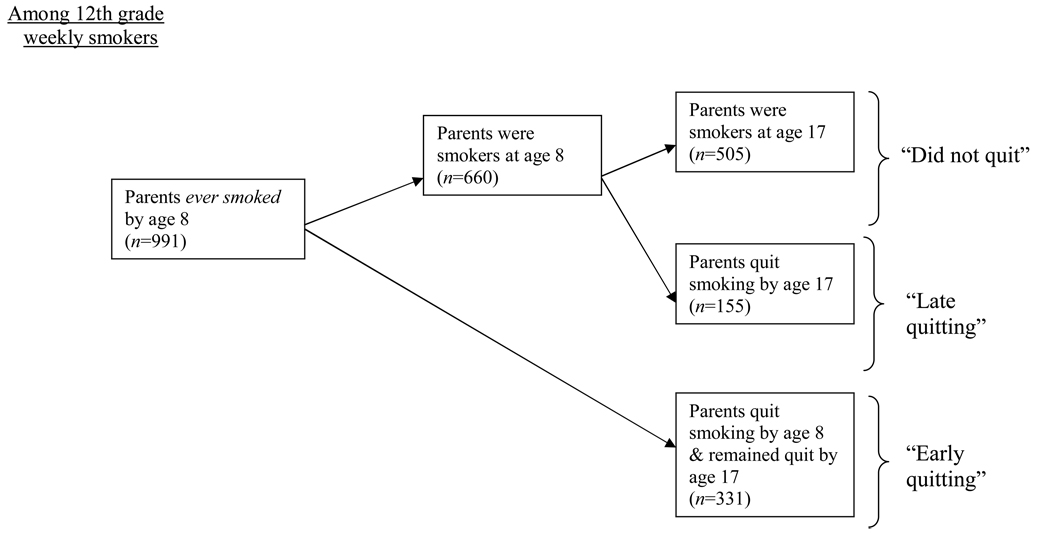

Participants were 991 at least weekly smokers at age 17 whose parents were ever regular smokers and who also reported their smoking status at age 28. Figure 1 presents the total sample of parent ever smokers, the “Did not quit” reference group, the “Early quitting” parent predictor, and the “Late quitting” parent predictor.

Figure 1.

Schematic of parents’ quit status.

Note: Among age 17 daily smokers, the schematic is the same, except the sample sizes are smaller: Among the 850 children with parents who ever smoked by age 8, 592 children had parents who currently smoked at age 8, 258 children had parents who quit by age 8, 461 children had parents who currently smoked at age 17, and 131 children had parents who quit by age 17.

The child participants were 49% female and 91% Caucasian. Ninety-five percent of the female parents and 81% of the male parents were biological parents.

Procedures

Mailed or telephoned surveys were used to collect parents’ early smoking cessation data when the children were age 8. Overall, 90% of the parents completed this survey. When the children were age 17, parents’ late smoking cessation data were collected via a mailed or telephoned survey with a 91% parent participation rate. Children's self-reported smoking behavior data were collected by classroom survey (by mailed or telephoned survey for non-responders) when the children were age 17, again when the children were age 19, and finally at age 28 by mailed and telephoned survey. Eighty-four percent of the children originally enrolled in the HSPP cohort at age 8 completed the age 28 survey.

Measures

Parents’ smoking status when children were age 8

Parents were asked this multiple-choice question when their children were age 8: "Do you use cigarettes?" The responses “Yes, occasionally” and “Yes, often” indicated they were current smokers, while the response “No, not anymore” indicated they had quit smoking. Self-reported smoking status is a relatively accurate indicator of biomarker validated smoking status [14–17]. The responding parent reported his/her smoking status and then gave a proxy report of the other parent’s smoking status. Adult proxy reports of other adult household members’ smoking status have shown high rates of concordance (86% to 96%) with those household members’ self-reports [18–20].

Parents’ smoking status when children were age 17

Parents’ smoking was also assessed when children were age 17 using the question, “Do you use cigarettes?” The responses “Yes, at least once a day” and “Yes, but not every day” indicated they were current smokers, while the response “No, not since [month/year]” indicated they had quit smoking. The responding parent self-reported his/her smoking status and then gave a proxy report of the other parent’s smoking status.

Children’s smoking status at age 17

The following questions, administered age 17, indicated whether the children were either daily or weekly smokers. In the in-class data collection or mailed survey, they were asked the question, "How often do you currently smoke cigarettes?" with responses ranging from “Have never smoked cigarettes” to “More than 20 cigarettes per day.” The primary response variable, daily smoking, was classified as "Yes" for responses "One to three cigarettes per day" to "More than 20 cigarettes per day" and "No" for responses "Have never smoked cigarettes" to "More than once a week, but less than once a day." Those participants surveyed by telephone were asked the question, "Do you smoke one or more cigarettes per day?" Participants who answered "Yes" were classified as daily smokers. Daily smoking was the primary response variable because it is an accepted smoking measure for 17 year-old children [6, 21] and because adolescent daily smokers are substantially more likely to report health problems and remain smokers as adults compared to those who smoke less than daily [4, 21]. Weekly smoking was a secondary response variable because it includes non-daily smokers whose smoking frequency is sufficient to be associated with symptoms of tobacco dependence [22, 23]. In the telephone survey, weekly smoking was defined by responses (1) and (2) to the question, “Do you smoke cigarettes…” (1) more than once a week, (2) once a week, or (3) less than once a week.

Because misreporting of tobacco use is a possibility among children [24–26], age 17 in-class participants were asked to provide a saliva specimen for cotinine analysis. Analysis of a 12.6% random sample of the specimens showed that 1.2% of children said they did not smoke but had cotinine evidence of smoking, while only 1.5% of children said they did smoke but had no cotinine evidence of smoking [6]. Given these small fractions of inconsistencies, the self-reported smoking status of these children was included in the analysis.

Young adult smoking status at age 28

The following question indicated that the adult children had quit: “When was the last time you smoked a cigarette?” Response options were: (1) within the last week, (2) within the last month, (3) 1–6 months ago, (4) 7–12 months ago, and (5) more than a year ago. At least 6 months of abstinence was defined as successful smoking cessation, as consistent with recommended definitions of successful abstinence among untreated smokers [27, 28].

Statistical analysis

Two predictor variables were used. The first was parents’ “early quitting”: smokers whose responding parent indicated on both the age 8 and 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent had quit and no parent was a current smoker. The second was parents’ “late quitting”: smokers whose responding parent indicated on the age 8 parent smoking survey that at least one parent currently smoked and no parent had quit smoking. In addition, the responding parent indicated on the age 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent had quit and no parent was currently smoking. There were two outcome variables: (1) 6-month abstinence among young adults who smoked at least daily at age 17, (2) 6-month abstinence among young adults who smoked at least weekly at age 17.

Computed first were the proportions of young adults’ smoking cessation according to parents’ smoking cessation status. Second, conditional logistic regressions were used to examine the prospective relationships between parents’ smoking cessation and their young adult children’s smoking cessation at age 28. For each investigation (parents’ early cessation, parents’ late cessation), regressions were performed separately for weekly and for daily smokers. The analyses controlled for child gender and parent education (an indicator of family-level socioeconomic status). Analysis also stratified on the 40 school districts [29], thereby accounting for (1) the intraclass correlation of smoking between participants within the same school district [30–32] and (2) variations in district-level socioeconomic status. The results are reported as odds ratios and associated confidence intervals.

Results

Educational characteristics of the parents and their children

As compared to parents who quit smoking (either earlier or late), parents who did not quit smoking were less likely to have completed high school or its equivalent (p < .001) and had a greater fraction of children who were high school dropouts (p < .001). There were no differences between the early and late parent quitting families on parent education or the fraction of their children who were high school dropouts (p >.05).

Parents’ and young adults’ smoking cessation rates

Thirty-three percent of the study sample had parents who quit early and 16% had parents who quit late. Overall, the young adult children’s 6-month quit rate at age 28 was 23.5% for those who smoked at least daily at age 17 and 25.9% for those who smoked at least weekly at age 17.

Young adult smoking cessation according to parents’ smoking cessation status

The proportion of young adults’ 6-month abstinence, occurring by age 28, according to their parents’ smoking cessation status is presented in Table 1. Among young adults who smoked at least daily at age 17 and whose parents indicated they did not quit smoking in both the age 8 and 17 parent surveys (n = 452), the 6-month quit rate was 19.7% (89/452). In contrast, among young adults who smoked daily at age 17 and whose parents quit early (n = 252), the 6-month quit rate was 30.2% (76/252). The 6-month quit rate was 27.3% (35/128) if their parents quit late. These results were similar for young adults who smoked at least weekly at age 17.

Table 1.

Age 28 six-month abstinence rates among with indicated age 17 smoking frequency and parents’ smoking cessation status.

| Parents’ cessation status |

Young adult 6-month abstinence at age 28 | |

|---|---|---|

| Among age 17 daily smokers | Among age 17 weekly smokers | |

| Did not quita | 19.69% | 20.84% |

| (89/452) | (104/499) | |

| Late quittingb | 27.34% | 29.14% |

| (35/128) | (44/151) | |

| Early quittingc | 30.16% | 33.64% |

| (76/252) | (109/324) | |

Smokers whose responding parent indicated on both the age 8 and 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent was a current smoker.

Smokers whose responding parent indicated on the age 8 parent smoking survey that at least one parent currently smoked and no parent had quit smoking. In addition, the responding parent indicated on the age 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent had quit and no parent was currently smoking.

Smokers whose responding parent indicated on both the age 8 and 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent had quit and no parent was a current smoker.

Prospective association between parents’ smoking cessation and young adult children’s smoking cessation

As shown in Table 2, young adults who smoked daily at age 17 and whose parents quit early had a 1.7 (OR = 1.70; 95% CI = 1.23, 2.36) times higher odds of quitting smoking as compared to those whose parents did not quit. These odds were slightly higher for young adults who were weekly smokers age 17 (OR = 1.91; 1.41, 2.58).

Table 2.

Odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) for the prospective associations between parents’ smoking cessation status and their young adult children’s smoking cessation.

| Parents’ cessation status |

Young adult 6-month smoking abstinenced | |

|---|---|---|

| Among 12th grade daily smokers |

Among 12th grade weekly smokers |

|

| Did not quita | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Late quittingb | 1.49 (0.90, 2.45) | 1.50 (0.96, 2.36) |

| Early quittingc | 1.70 (1.23, 2.36) | 1.91 (1.41, 2.58) |

Smokers whose responding parent indicated on both the age 8 and 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent was a current smoker.

Smokers whose responding parent indicated on the age 8 parent smoking survey that at least one parent currently smoked and no parent had quit smoking. In addition, the responding parent indicated on the age 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent had quit and no parent was currently smoking.

Smokers whose responding parent indicated on both the age 8 and 17 parent smoking survey that at least one parent had quit and no parent was a current smoker.

Controlled for child gender and parent education.

Young adults who smoked daily at age 17 and whose parents quit late had a 1.49 (OR = 1.49; 95% CI = 0.90, 2.45) times higher odds of quitting smoking as compared to those whose parents did not quit. However, the lower bound of the confidence interval was outside of statistical significance. These odds were similar for young adults who were weekly smokers at age 17, but were also just outside the significant range.

Discussion

Overall results

This study examined the long-term prospective relationship between parents’ smoking cessation and their young adult children’s smoking cessation. Overall, parents’ smoking cessation was associated with substantially higher odds of their young adult children’s smoking cessation. Specifically, the link between parents’ smoking cessation and their children’s smoking cessation is not limited to the short term (i.e., age 19; [11]) but remains significant, much later, by the developmentally important age of 28 [8].

Parents’ early smoking cessation

Results showed that parents’ early smoking cessation is important for both age 17 daily and weekly smokers. Furthermore, there is suggestive evidence of a stronger effect for age 17 weekly smokers: the point estimate for the odds ratio of 6-month abstinence among weekly smokers (i.e., 1.91) was higher than the corresponding point estimate among daily smokers (i.e., 1.70). However, interpretation of this comparison is tempered by the fact that the two odds ratios were not significantly different, as evidenced by their overlapping confidence intervals.

Parents’ late smoking cessation

There was also suggestive evidence (borderline non-significant association) that parents’ late smoking cessation leads to a higher odds of their young adult children’s smoking cessation by age 28 among those children who smoked either daily or weekly at age 17. This result might be due to a lack of power, even though there was a substantial number of parents who both quit late and had young adult children who quit smoking. Future research with a larger sample might definitively determine if this suggestive association is significant. Overall, parents’ early and late smoking cessation may increase the odds of their children quitting smoking, but the impact of parents’ early smoking cessation is the most enduring and conclusive.

Public health implications

Public health interventions can inform parents that quitting smoking (a) reduces the odds that their children will become smokers [33] and (b) increases the odds their children will quit smoking by time they are young adults. These effects have their greatest potential impact if they occur by the time their children reach age 8. Helping parents quit smoking should be included in youth smoking interventions [11].

Theoretical implications

While there are number of possible underlying mediators and moderators of the observed associations, including genetic and neurological factors [34, 35, 36], the findings of this study are consistent with Social Cognitive Theory’s [SCT; 37, 38] delayed modeling hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that a long time may elapse before a parents’ past modeled behavior is actually put into practice because the opportunity for the child to use what he/she learned from his/her parents might not arise until a long time later [37, 38]. In other words, children may eventually quit smoking because they remember and later adopt their parents’ past quitting behavior. Beyond this hypothesis, parents who quit smoking may teach and communicate health values that eventually motivate their young adult children to quit smoking. Another possibility is that both parents and children share genetic factors associated with a higher odds of quitting smoking. Overall, these hypotheses need study in future research.

Limitations

While the current study’s use of 6-month cessation outcomes overcomes a key limitation of the two prior studies on this topic [11, 12], this study nonetheless has important limitations, beyond those stated above, that need to be addressed in future research. First, a biochemical validation of parent and child smoking cessation would have been valuable. Second, although this study’s sample was representative of Washington State, it was only 10% non-Caucasian and the sample was from the US and thus results may not generalize to non-Caucasians and samples taken in other countries. Finally, a randomized controlled trial to help parents quit would test whether the parent cessation–child cessation link established in this study is merely associational, or causal.

Conclusion

The present study provides the new finding that parents’ early smoking cessation predicts their young adult children’s 6-month smoking cessation by age 28. Parents who smoke should be encouraged to quit when their children are young.

Acknowledgments

The data for this paper were provided by the Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project, a project funded by National Cancer Institute grant CA-38269. The data were collected with the approval of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center’s Institutional Review Board and with informed consent of the respondents. The paper was written with the support of National Cancer Institute grant CA-109652.

We thank the children and parents in the study who provided information about their smoking behaviors.

References

- 1.CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2005;54:1121–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56:1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmen TL, Barrett-Connor E, Holmen J, Bjermer L. Health problems in teenage daily smokers versus nonsmokers, Norway, 1995–1997: The Nord-Trondelag Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151:148–155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machuca G, Rosales I, Lacalle JR, Machuca C, Bullon P. Effect of cigarette smoking on periodontal status of healthy young adults. Journal of Periodontology. 2000;71:73–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson AV, Mann SL, Kealey KA, Marek PM. Experimental design and methods for school-based randomized trials: experience from the Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project (HSPP) Controlled Clinical Trials. 2000;21:144–165. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnson LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, Drinking, and Drug Use in Young Adulthood: The Impacts of New Freedoms and Responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDermott L, Dobson A, Owen N. Occasional tobacco use among young adult women: a longitudinal analysis of smoking transitions. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:248–254. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychology. 2000;19:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bricker JB, Rajan KB, Andersen MR, Peterson AV., JR Does parental smoking cessation encourage their young adult children to quit smoking? A prospective study. Addiction. 2005;100:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mcgee R, William S, Reeder A. Parental tobacco smoking behaviour and their children's smoking and cessation in adulthood. Addiction. 2006;101:1193–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson AV, Kealey KA, Mann SL, Marek PM, Sarason IG. Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project (HSPP): A long-term randomized trial in school-based tobacco use prevention. Results on smoking. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:1979–1991. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.24.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attebring MF, Herlitz J, Berndt AK, Karlsson T, Hjalmarson A. Are patients truthful about their smoking habits? A validation of self-report about smoking cessation with biochemical markers of smoking activity among patients with ischaemic heart disease. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2001;249:145–151. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray DM, O’Connell CM, Schmid LA, Perry CL. The validity of smoking self-reports by adolescents: A reexamination of the bogus pipeline procedure. Addictive Behavior. 1987;12:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, et al. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray RP, Connett JE, Lauger GG, Voelker HT The Lung Health Study Research Group. Error in smoking measures: Effects of intervention on relations of cotinine and carbon monoxide to self-reported smoking. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:1251–1257. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.9.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyland A, Cummings KM, Lynn WR, Corle D, Gifeen C. Effect of proxy-reported smoking status on population estimates of smoking prevalence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145:746–751. doi: 10.1093/aje/145.8.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson LM, Longstretch WT, Koepsell TD, Checkoway H, van Belle G. Completeness and accuracy of interview data from proxy respondents: Demographic, medical and life-style factors. Epidemiology. 1994;5:204–217. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnitzler PG, Olshan AF, Savitz DA, Erikson JD. Validity of mother’s report of father’s occupation in a study of paternal occupation and congenital malformations. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;141:872–877. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Survey Results on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future Study, 1975–1998, Vol. II. NIH publication no. 99–4661. 1999:30–35.

- 22.Barker D. Reasons for tobacco use and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal among adolescents and young adult tobacco smokers—United States, 1993. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1994;43:745–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, Coleman M, Wood C. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:228–235. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luepker RV, Pallonen UE, Murray DM, Pirie PL. Validity of telephone surveys in assessing cigarette smoking in young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1988;79:202–204. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray DM, O’Connell CM, Schmid LA, Perry CL. The validity of smoking self-reports by adolescents: A reexamination of the bogus pipeline procedure. Addictive Behavior. 1987;12:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pechacek TF, Murray DM, Luepker RV, Mittelmark MB, Johnson CA, Shutz JM. Measurement of adolescent smoking behavior: Rationale and methods. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1984;7:123–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00845351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Vol 1. Lyon: IARC Scientific Publications; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray DM. Design and Analyses of Group-Randomized Trials. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donner A, Brown KS, Brasher P. A methodological review of non-therapeutic intervention trials employing cluster randomization. 1979–1989. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;19:795–800. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson JM, Klar N, Donner A. Accounting for cluster randomization: A review of primary prevention trials, 1990 through 1993. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:1378–1383. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.10.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bricker JB, Leroux BG, Peterson AV, Kealey KA, Sarason IG, Andersen MR, Marek PM. Nine-year prospective relationship between parental smoking cessation and children’s daily smoking. Addiction. 2003;98:585–593. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kardia SL, Pomerleau CS, Rozek LS, Marks JL. Association of parental smoking history with nicotine dependence, smoking rate, and psychological cofactors in adult smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1447–1452. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White VM, Hopper JL, Wearing AJ, Hill DJ. The role of genes in tobacco smoking during adolescence and young adulthood: A multivariate behaviour genetic investigation. Addiction. 2003:1087–1100. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Addiction. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:25–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]