Abstract

Objective To identify predictors of perinatal and infant mortality variations between primary care trusts (PCTs) and identify outlier trusts where outcomes were worse than expected.

Design Prognostic multivariable mixed models attempting to explain observed variability between PCTs in perinatal and infant mortality. We used these predictive models to identify PCTs with higher than expected rates of either outcome.

Setting All primary care trusts in England.

Population For each PCT, data on the number of infant and perinatal deaths, ethnicity, deprivation, maternal age, PCT spending on maternal services, and “Spearhead” status.

Main outcome measures Rates of perinatal and infant mortality across PCTs.

Results The final models for infant mortality and perinatal mortality included measures of deprivation, ethnicity, and maternal age. The final model for infant mortality explained 70% of the observed heterogeneity in outcome between PCTs. The final model for perinatal mortality explained 80.5% of the between-PCT heterogeneity. PCT spending on maternal services did not explain differences in observed events. Two PCTs had higher than expected rates of perinatal mortality.

Conclusions Social deprivation, ethnicity, and maternal age are important predictors of infant and perinatal mortality. Spearhead PCTs are performing in line with expectations given their levels of deprivation, ethnicity, and maternal age. Higher spending on maternity services using the current configuration of services may not reduce rates of infant and perinatal mortality.

Introduction

In England infant mortality has been steadily declining, but this trend belies significant inequalities in avoidable deaths.1 Young mothers, those from lower socioeconomic groups, and those from some minority ethnic communities have consistently worse outcomes compared with the rest of the population.2 The latest report of the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health indicates that the underlying risk factors of perinatal mortality cluster around young and old maternal age, high levels of social deprivation, and minority ethnic groups.3

In order to address health inequalities and reduce the current level of infant mortality in the UK, the government introduced targets in 2003 to reduce the relative gap in infant mortality by at least 10% between the “routine and manual groups” (the lowest social class category in a three-class analytical structure) and the population as a whole.4 Data available from the introduction of the Public Service Agreement target indicate that the rates of both infant and perinatal mortality remain high in many primary care trusts (PCTs), and the target seems challenging given the current performance across the NHS.5

PCTs that have been identified with particularly poor performance data have been assigned “Spearhead” status by the Department of Health.6 Spearhead status is intended to reflect those areas with the worst health and deprivation indicators. It describes the PCTs that map on to the local authority areas that are in the bottom fifth nationally for three or more of the following factors:

Male life expectancy at birth

Female life expectancy at birth

Cancer mortality in the under 75s

Cardiovascular disease mortality in the under 75s

Average score on the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2004 (local authority summary).

There is increasing interest in the levels of performance of PCTs particularly in areas such as infant and perinatal mortality. Although Spearhead PCTs have inferior health outcomes by definition, it is unclear whether such outcomes arise from poor service provision and lack of expenditure or from patient demographics such as deprivation or ethnicity. It is also unclear whether variation in NHS service provision contributes to variation in outcome.

The aim of this study was to develop multivariable prognostic models to identify potential causes of variability in the rates of infant and perinatal mortality between the 303 PCTs in England and to identify PCTs with worse than expected outcomes. Potential causes of variability between PCTs included population characteristics, such as ethnicity and deprivation, and health service funding for maternity services.

Methods

Data sources

From the National Centre for Health Outcomes Development,7 we identified data on the number of infant and perinatal events and their rate per 1000 births, mothers’ age at giving birth, and the ethnicity of residents in each PCT. We obtained further data on deprivation scores for each PCT from the English Indices of Deprivation8 and estimates of PCT spending on maternity services (excluding fertility services) from the Department of Health5 and expressed as spending per birth (see box). Maternal age was categorised by the Office for National Statistics into <16 years, <18 years, and >35 years. We also identified categorisation of PCTs into Spearhead status.6 Spending estimates and infant and perinatal mortality rates were available for the years 2003 to 2005, but for the other explanatory variables we had access only to data from a single time point.

PCT characteristics included as candidate variables in model building process for both infant mortality and perinatal mortality

Infant mortality events (the number of deaths of infants (1 year of age or younger)) and rates per 1000 live births7

Perinatal mortality events (deaths occurring during late pregnancy (at ≥24 completed weeks’ gestation), during childbirth, and up to seven completed days of life) and rates per 1000 births7

English Indices of Deprivation score for each PCT8

Spearhead status of PCT6

Ethnicity for the PCT population7—mixed, black, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi/other Asian, Chinese, white (comparator)

Mother’s age at birth7—<16 years, <18 years, >35 years

PCT expenditure (estimated) on maternity and reproductive health (except fertility) per birth in England5

Although we had recognised that measures of parity and smoking behaviour among mothers were important potential explanatory variables to include in our model, the data were incomplete or unavailable. Parity was recorded only for married subjects,7 and estimated smoking behaviour was available consistently only for the PCT area as a whole and not for women at the time of birth.7 Because of the potential for confounding by inclusion of this partial information, we determined that results from a statistical model including these terms would prove impossible to interpret and thus did not include parity scores or smoking behaviour as candidate explanatory variables in the final model building process. Included variables and their sources are described in the box.

Statistical analysis

Following the general approach described by Harrell et al,9 we developed prognostic models identifying predictors of infant or perinatal mortality in order to examine the extent to which these variables may account for observed variation between PCTs. We developed Poisson mixed models, in which the observed number of events was the response variable. The models used a log link and Poisson-normal error structures, with the natural log of the population size (births) specified as an offset (weighting) variable. Ethnicity, mothers’ age at birth, and expenditure rates per birth were log transformed for model stability. Where PCT rates of a candidate explanatory variable were close to zero we used a continuity correction (log(1+p), where p is the fractional rate) to avoid potential excess influence. Both the PCT Chinese population birth rate and maternal age <16 years birth rate were rare, and we used the continuity correction. Extra-Poisson variability (over-dispersion) at the level of the PCT was anticipated and was addressed principally through defining PCTs as random effects.10

A limited number of prespecified characteristics of the PCT—including ethnicity, maternal age, deprivation, and funding of services—were examined in the resulting statistical models (see box). Backward model selection was used to derive separate models for infant mortality and perinatal mortality. The α level required to remain in the model was 5%. Non-linear predictors were included in the model as log transformed variables or restricted cubic splines if these were sequentially established to be significantly superior to the untransformed data, with the best fitting model selected on the basis of residual pseudolikelihood.

As spending on maternity services was available for each year included, we examined the year on year effect of changes in spending on infant and perinatal mortality rates by fitting a more complex repeated measures analysis including a within-PCT spending term by year. These additional analyses served to answer the question of whether changes in spending over time were associated with subsequent changes in outcome. Otherwise, data from the three years were combined.

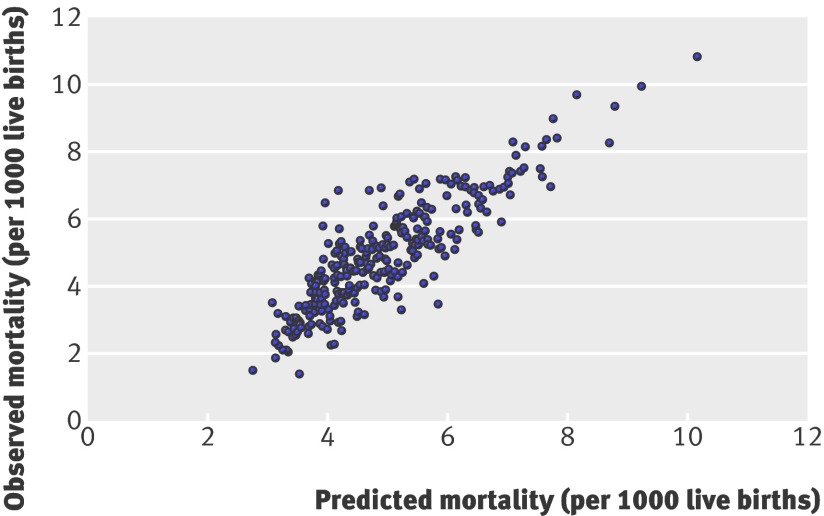

We used the models to derive predicted event rates for each PCT for infant mortality and perinatal mortality, and compared predicted and observed rates. The observed and predicted rates were described and plotted. Outliers worthy of further attention for both outcomes were defined as those PCTs for which the observed rate differed from the expected rate by more than three studentised residual errors.

For each final model we calculated the extent to which heterogeneity (extra-Poisson variability) between PCTs was “explained” by the included parameter terms. Model validation assessing potential optimism due to over-fitting was conducted using the bootstrap algorithm described by Harrell et al.9 Briefly, 200 bootstrap samples were drawn from the original datasets, and, following the original procedure, models were fitted using backward selection to each dataset and the R2 calculated. The new models were in each case forced into the original dataset, and the R2 calculated for that fit. The difference between the model fits is an unbiased estimate of the level of optimism derived from the model fitting process.

Analyses were conducted in the statistical package SAS v 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (R Development Core Team 2007).

Results

Rates of infant and perinatal mortality and PCT level demographics

We identified data for all 303 PCTs in England. Spearhead status was designated in 88 (29%). Because of changing boundaries, data on deprivation status was not available for two PCTs. All other data were complete. There was substantial and striking variability in rates of infant and perinatal mortality, deprivation, spending on maternity services, age of mothers, and ethnicity across the PCTs. The median PCT population was 154 075 (interquartile range 112 459 to 200 435). Rates of infant mortality varied by PCT from 1.4 to 10.83 deaths/1000 live births for the three years of our study, and perinatal mortality varied from 3.93 to 16.66/1000 births. Table 1 shows the infant and perinatal mortality rates over the three year study period, and the candidate explanatory variables which were examined in the statistical models.

Table 1.

Infant and perinatal mortality per 1000 live births, and candidate explanatory variables by primary care trust in England

| Variable | Median (IQR) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant mortality per 1000 live births | 4.81 (3.80-5.89) | 1.40 | 10.83 |

| Perinatal mortality per 1000 live births | 7.81 (6.69-9.07) | 3.93 | 16.66 |

| Deprivation index | 19.45 (13.34-28.20) | 5.09 | 58.67 |

| Maternity spend per birth (£) | 4569 (3893-5217) | 1897 | 8904 |

| Birth rate by maternal age (%): | |||

| <18 years | 1.95 (1.32-2.86) | 0.41 | 6.05 |

| <16 years | 0.16 (0.10-0.27) | 0.00 | 0.75 |

| >35 years | 19.14 (15.01-23.29) | 9.08 | 39.48 |

| Birth rate by ethnicity (%): | |||

| Mixed race | 0.86 (0.56-1.42) | 0.23 | 4.83 |

| Black | 0.38 (0.18-1.21) | 0.02 | 25.90 |

| Pakistani | 0.18 (0.06-1.11) | 0.01 | 40.76 |

| Indian | 0.51 (0.21-1.66) | 0.04 | 38.02 |

| White | 96.83 (91.47-98.42) | 29.13 | 99.45 |

| Bangladeshi or other Asian | 0.28 (0.13-0.75) | 0.03 | 34.33 |

| Chinese | 0.28 (0.17-0.47) | 0.07 | 2.25 |

IQR = interquartile range.

Ethnic categories: white = white British + white Irish + white other; mixed race = mixed white-Caribbean + mixed white-African + mixed white-Asian + mixed other; black = black Caribbean + black African + black other.

Within-PCT effects of spending on childhood and maternity services

The univariate within-PCT models examining yearly spending on maternity services are described in tables 2 and 3. Since we found no statistically significant predictive effect between yearly spending on outcome for either perinatal mortality or infant mortality, all subsequent analyses were conducted using the three year period combined.

Table 2.

Predictors of infant mortality by primary care trust in England—univariate models

| Item | Relative risk (95% CI)* | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Deprivation index | 1.018 (1.015 to 1.020) | <0.0001 |

| Spearhead status | 1.365 (1.274 to 1.462) | <0.0001 |

| Birth rate by ethnicity†: | ||

| Mixed race | 1.123 (1.068 to 1.180) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 1.058 (1.033 to 1.082) | <0.0001 |

| Indian | 1.063 (1.037 to 1.090) | <0.0001 |

| Pakistani | 1.080 (1.061 to 1.099) | <0.0001 |

| Bangladeshi or other Asian | 1.071 (1.043 to 1.101) | <0.0001 |

| Chinese‡ | 4.66×102 (4.98×10−2 to 4.37×106) | 0.187 |

| Maternity spend per birth over 3 year period† | 0.709 (0.615 to 0.818) | <0.0001 |

| Yearly maternity spend by year† | 0.920 (0.834 to 1.015) | 0.095 |

| Birth rate by maternal age: | ||

| <16 years‡ | 4.12×1026 (3.90×1015 to 4.34×1037) | <0.0001 |

| <18 years† | 1.341 (1.255 to 1.431) | <0.0001 |

| >35 years† | 0.553 (0.495 to 0.618) | <0.0001 |

*Relative risk of a unit change in the X value (that is, antilog of parameter estimate).

†Log transformed rate.

‡Log transformed (fractional rate+1).

Table 3.

Predictors of perinatal mortality by primary care trust in England—univariate model

| Item | Relative risk (95% CI)* | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Deprivation index | 1.014 (1.012 to 1.016) | <0.0001 |

| Spearhead status | 1.275 (1.208 to 1.345) | <0.0001 |

| Birth rate by ethnicity†: | ||

| Mixed race | 1.138 (1.097 to 1.182) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 1.067 (1.049 to 1.085) | <0.0001 |

| Indian | 1.072 (1.052 to 1.091) | <0.0001 |

| Pakistani | 1.072 (1.058 to 1.086) | <0.0001 |

| Bangladeshi or other Asian | 1.079 (1.058 to 1.101) | <0.0001 |

| Chinese‡ | 1.34×104 (1.16 to 1.56×107) | 0.009 |

| Maternity spend per birth over 3 year period† | 0.764 (0.683 to 0.855) | <0.0001 |

| Yearly maternity spend by year† | 0.916 (0.836 to 1.047) | 0.056 |

| Birth rate by maternal age: | ||

| <16 years‡ | 1.53×1017 (2.58×108 to 9.08×1025) | 0.0001 |

| <18 years† | 1.199 (1.137 to 1.265) | <0.0001 |

| >35 years† | 0.649 (0.595 to 0.709) | <0.0001 |

*Relative risk of a unit change in the X value (that is, antilog of parameter estimate).

†Log transformed rate.

‡Log transformed (fractional rate+1).

PCT level predictors of infant mortality

Out of the 12 candidate variables, the final model for infant mortality included three which were highly statistically significantly predictive of outcome (see tables 2 and 4). Log transformation did not improve the model fit for the index of deprivation score, so the untransformed continuous score was included in the final model. Increased birth rates at the PCT level of deprivation, Pakistani population, and maternal age <18 years were significant predictors of increased levels of infant mortality. The final fitted model explained 70.0% of the between-PCT heterogeneity in infant mortality.

Table 4.

Predictors of infant mortality by primary care trust in England—multivariable model

| Effect | Relative risk (95% CI)* | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 10.915 (7.625 to 15.625) | <0.0001 |

| Deprivation index | 1.009 (1.006 to 1.013) | <0.0001 |

| Birth rate by Pakistani ethnic group† | 1.056 (1.038 to 1.074) | <0.0001 |

| Birth rate by maternal age <18 years† | 1.192 (1.115 to 1.274) | <0.0001 |

*Relative risk of a unit change in the X value (that is, antilog of parameter estimate).

†Log transformed rate.

Extra-Poisson variance explained in final model = 70.0%.

PCT level predictors of perinatal mortality

Out of the 12 candidate variables, the final model for perinatal mortality included four which were statistically significantly predictive of outcome (see tables 3 and 5). Again, log transformation did not improve the model for the index of deprivation score, so the untransformed continuous score was included in the final model. Increased PCT level birth rates associated with black ethnicity and deprivation were strong determinants of increased perinatal mortality, while maternal age >35 years at birth was associated with decreased rates of perinatal mortality. We also observed a weak detrimental effect for the PCT level birth rates associated with Pakistani ethnicity. The final fitted model explained 80.5% of the between-PCT heterogeneity in perinatal mortality.

Table 5.

Predictors of perinatal mortality by primary care trust in England—multivariable model

| Effect | Relative risk (95% CI)* | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 5.990 (5.131 to 6.992) | <0.0001 |

| Deprivation index | 1.006 (1.003 to 1.008) | <0.0001 |

| Birth rate by Pakistani ethnic group† | 1.019 (1.003 to 1.036) | 0.0197 |

| Birth rate by black ethnic group† | 1.047 (1.027 to 1.069) | <0.0001 |

| Birth rate by maternal age >35 years† | 0.742 (0.667 to 0.824) | <0.0001 |

*Relative risk of a unit change in the X value (that is, antilog of parameter estimate).

†Log transformed rate.

Extra-Poisson variance explained in final model = 80.5%.

Observed versus predicted infant and perinatal mortality by PCT

The relationship between observed and predicted infant mortality and perinatal mortality are described in figures 1 and 2 respectively. For infant mortality, no PCTs had observed rates that differed by more than three studentised residual errors from their predicted rate from the multivariable analysis. For perinatal mortality, in two PCTs the observed rate was substantially higher than the expected rate (see table 6). Neither of the trusts with extreme results was categorised as Spearhead status.

Fig 1 Observed versus predicted infant mortality by primary care trust in England

Fig 2 Observed versus predicted perinatal mortality by primary care trust in England

Table 6.

Details of primary care trusts in England where observed perinatal mortality differed by more than three studentised residual errors from predicted mortality

| Trust name | Studentised residual deviance | Spearhead status | Total perinatal mortality | Perinatal mortality rate/1000 births | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Predicted | Observed | Predicted | ||||

| South Hams and West Devon PCT | 3.98 | No | 34 | 18.83 | 12.29 | 6.81 | |

| Wyre Forest PCT | 3.96 | No | 41 | 24.26 | 13.41 | 7.93 | |

Model validation

The models for infant and perinatal mortality were validated using the approach described by Harrell et al.9 For infant mortality the estimate of model optimism derived from the bootstrap process was 4.6%, and for perinatal mortality it was 3.9%.

Discussion

We developed prognostic models that used available data to predict differences in infant and perinatal mortality at the level of a PCT. The results from both models show clearly the importance of deprivation, ethnicity, and maternal age as risk factors—although the design of this study, based on aggregated data at the PCT level, precludes testing the presumption that these relationships are directly causal. Both models explained substantial amounts of the observed variability between PCTs, with the final model for infant mortality explaining 70.0% of the between-PCT heterogeneity, and the final model for perinatal mortality explaining 80.5% of the between-PCT heterogeneity. These results were achieved through the application of a parsimonious model fitting strategy designed to avoid optimism due to overfitting. The validation process we conducted confirmed that the level of optimism was low in each fitted model, indicating that the results are sound and may be generalisable.

Our analyses aimed to develop models to account for systematic variation (heterogeneity) in infant and perinatal mortality between PCTs. Caution is required in attempting to interpret the parameter estimates from the statistical models since relationships observed at the PCT level may not apply directly to individual subjects because of ecological confounding. For instance, the apparent protective effect of maternal age >35 years for perinatal mortality described in table 3 seems counterintuitive and contrary to expectations3 until we consider that older mothers receive more intensive monitoring and intervention during pregnancy, and that they are more likely to be from higher social class and thus subject to any protective effects associated with social advantage. Indeed, the higher rate of maternal age may simply reflect broader characteristics of the PCT related to improved outcome rather than any characteristic directly of older mothers. Further, care is required in interpreting the relative risks provided, which are often subject to log transformation to aid model fit, and which relate to a 1 unit change in the candidate predictive variable. Since several of the variables (such as maternal age <16 years or Chinese ethnicity) are associated with very low birth rates in the population, the relative risks imply a very large difference in risk but are applied to a very low incident risk of events.

The Index of Multiple Deprivation 20048 is a measure of multiple deprivation at the small area level. The model that underpins this index is based on the idea of distinct dimensions of deprivation which can be recognised and measured separately.8 The index performed well in our study, on its own explaining 54% of the heterogeneity between PCTs in the infant mortality model and 57% of the heterogeneity for the perinatal mortality model. This is despite the aggregation of the measure to PCT level.

We examined the effects of spending on maternity services by PCT in repeated measures models across the three years of data, to see if changing funding levels led to differences in outcome. Our results were not statistically significant either for infant or perinatal mortality. Since we found no convincing evidence of a year on year change in outcome associated with spending, we aggregated the data over three years to provide a more robust analysis set less susceptible to chance annual effects in these rare but important events. We found no evidence of an effect of spending in those analyses either.

Increased spending on maternity services will lead to improvements in outcome only when resources are directed to interventions which are effective. A recent large trial examining the effects of an antenatal peer support intervention to encourage breast feeding initiation, for example, provided no evidence of effect for this intervention, which had been considered a strong candidate for adoption.11 Indeed, it is well established that determinants of infant mortality outside health services have a more profound effect than the provision of health care per se.12 Because of this interplay of many complex factors, it will clearly be necessary for many different agencies to work together if the national target in this area is to be achieved.1

The raised risk of infant and perinatal mortality among Pakistanis could be linked to consanguineous marriages,13 but this remains controversial.14 15 In common with other predictors included in the models, we cannot be certain whether the observed relationship is causal or the result of Pakistani ethnicity being related to another factor or factors not otherwise captured in the models. Consanguineous marriages are found throughout the world and not restricted to the Muslim community.15 These marriages can lead to an increase in rare, recessively inherited disorders, but the effect of this on the disease patterns of the population as a whole may have been exaggerated.15 Further, since estimated ethnicity is based on the PCT population rather than those accessing maternity services, the pattern of ethnicity included in our study may capture characteristics of the PCT population related to perinatal and infant mortality rather than directly relate to the identified ethnic group. However, other work based on individual subject data has noted an increased risk of infant and perinatal mortality among mothers of Pakistani origin.16

Except for two PCTs, both models show high predictive values (figs 1 and 2) and suggest that all trusts, including those with Spearhead status, had perinatal and infant outcomes consistent with the demographic composition of the communities they serve. The two apparently poorly performing trusts were merged into larger trusts during the NHS reorganisation in 2006. South Hams and West Devon PCT now forms part of Devon PCT, and Wyre Forest PCT was merged with Redditch & Bromsgrove PCT and South Worcestershire PCT to form Worcestershire PCT. It is not clear why these two trusts had such high event rates compared with the expected rates for their characteristics. Scrutinising the figures for individual years, it is apparent that the results are not the product of an anomaly or peak during a single year. There is a risk that high event rates may not be identified in PCTs that do not have extreme results when compared crudely with other PCTs (such as those trusts that appear in the middle of the distribution of results). Multivariable analyses such as that presented here go some way to rectifying this situation. However, such analyses simply demonstrate that results are extreme without identifying causes of this finding. Further local scrutiny is required in order to ascertain the likely causes and potential solutions for these extreme results.

For the first time, estimated budgetary data on the amount PCTs spend on maternity and reproductive services were available and incorporated in the analysis. Programme budgeting is a developing tool for commissioning public health programmes and health services. Programme budgeting allows PCTs to compare expenditure and health outcomes in a systematic way17 18 and to identify where their performance is an outlier. This approach cannot, however, answer questions about the relationship between the different ways in which health expenditure is applied to a service. Furthermore, there may be local differences in the range and type of services which PCTs group together when they submit their expenditure data by programmes. Such variations may obfuscate any observations about the direct relationship between levels of investment and outcomes, and may be one of the reasons why we found no relationship between expenditure and infant or perinatal mortality. Our study does, however, strongly illustrate the importance of taking ethnicity into account when making comparisons and drawing inferences about the relationship between health expenditure and health outcomes in future.

The implications of this study are that national monitoring of Spearhead PCTs’ performance against key health outcomes such as infant mortality that are not adjusted for key demographic factors (such as deprivation, ethnicity, and maternal age) are unlikely to be useful or fair. The concept of “added value,” commonly used in the education sector to assess year on year improvements, may present a better approach. Comparative assessment and advice on levels of expenditure is unlikely to result in better outcomes per se since there does not seem to be a direct causal relationship. Instead, areas with poor outcomes should be expected to assess performance using proxy outcomes, assess activity and expenditure data that are available, undertake specific service reviews, invest in models of maternity care that are most likely to meet the demographic needs of the populations they serve, and compare the costs, efficiency, and quality of care given by different providers with whom they place contracts.

Our study is original. Previous authors have described studies addressing related but discrete topics. Adam et al described the estimated cost effectiveness of a range of maternity services in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia.19 They assessed many services: a community based, newborn care package followed by antenatal care (tetanus toxoid, screening for pre-eclampsia, screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and syphilis); skilled attendance at birth with first level maternal and neonatal care around childbirth and emergency obstetric and neonatal care around and after birth; screening and treatment of maternal syphilis; community based management of neonatal pneumonia, and steroids given during the antenatal period. However, such services are already commonly in place in healthcare systems in higher income countries. Bakeo examined the relationship between mothers’ countries of birth and outcome, also examining the role of fathers’ occupation (manual or non-manual), birth weight, and marital status in births between 1983 and 2001 in England and Wales.16 Bakeo’s findings were broadly in line with our own for the risk factors examined, but in that work no examination of variation at the PCT level was undertaken, deprivation was not addressed directly (but only through the father’s occupation), and maternity services funding was not addressed. Glinianaia et al examined trends in perinatal mortality between 1982 and 2000, finding that changes in the incidence of low birth weight attenuated the otherwise positive trend in the reduction of perinatal mortality. Again, no examination of variation in rates of events at the level of the PCT was conducted, or examination of the effects of spending on maternity services.20 Nixon and Ullman conducted an econometric model to examine the relationship between total healthcare funding and a range of population health outcomes in 15 countries from the EU between 1980 and 1995, concluding that overall health spending was strongly associated with a reduction in infant mortality during the period.21 However, the authors did not address the question of variation at the PCT level, deprivation, maternal characteristics, ethnicity, or spending on maternity services.

Limitations of study

We undertook an ecological analysis of factors that predict infant and perinatal mortality, two related measures that include many of the same deaths. The finding from the multivariable analysis indicating that older maternal age is a protective factor was unexpected. Caution is clearly warranted here about drawing any conclusions on causation on this or any other included factors, because an association at the PCT level does not guarantee that the association will hold at the individual level.22 Furthermore, it may not be possible to assess the strength of the exposure-outcome relationship using ecological data since, for example, the deprivation index value derived for the PCT might include pockets of extremes of deprivation and wealth. Our prior understanding of the likely risk factors for infant and perinatal mortality and the very strong and consistent effects of deprivation in the models makes it highly plausible that deprivation has a direct negative effect. The effect of maternal age, albeit strong statistically, is not in line with our prior understanding and thus may be considered likely to be confounded by other unmeasured factors aliased to that factor. Limitations with available data meant that we were not able to include mothers’ smoking behaviour or parity in the statistical models, factors which may have explained substantial variation at the PCT level. Estimated data on PCT spending on maternity services (excluding fertility services) is based on PCT “PFR4” financial returns and strategic health authority “HFR30” forms, sent to the Department of Health as part of the annual financial returns process, and may be subject to some inaccuracy. Nevertheless, the results are valuable, enabling us to draw inferences about the experiences of whole communities and in doing so provide information on the level of avoidable deaths experienced within communities.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that it is possible to examine community levels of deprivation, ethnicity, and maternal age and to largely explain heterogeneity in perinatal and infant mortality outcomes between PCTs in England. Most PCTs can be confident on the basis of these findings that the social conditions and ethnicity of the communities they serve are more important determinants of these particular health outcomes than current variation in levels of expenditure on maternity services. Nevertheless, the absolute rates of infant and perinatal mortality remain high in parts of England, and the burden of avoidable deaths remains largely with deprived communities and ethnic minorities.

What is already known on this topic?

There is substantial heterogeneity in infant and perinatal mortality between primary care trusts (PCTs) in England

Around 30% of PCTs with the worst health and deprivation indicators have been given Spearhead status, requiring special attention

No study has attempted to account for between-PCT variability in infant and perinatal mortality on the basis of known population risk factors and PCT spending

What this study adds

Between 70% and 80% of between-PCT variability in infant and perinatal mortality can be explained by a combination of deprivation, ethnicity, and maternal age

Differences in PCT spending, either between-PCT or over time, do not reliably explain differences in rates of infant and perinatal mortality

Although having higher rates of infant and perinatal mortality, Spearhead PCTs do not have results out of line with the risks in their populations. Neither of the two PCTs identified as having higher than expected rates of perinatal mortality had Spearhead status

Contributors: CG, NF, and JC conceived the idea for the study. All authors contributed to the design of the study, the interpretation of the results, and the writing of the paper. NF and JW designed and conducted the statistical analyses. NF is the guarantor.

Funding: Funded by the Birmingham Health and Wellbeing partnership.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not needed for this study.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b2892

References

- 1.Department of Health. Tackling health inequalities: 2003-05 data update for the national 2010 PSA target. December 2006www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_063689 (accessed 12/3/08).

- 2.Gill PS, Kai J, Bhopal RS, Wild S. Health care needs assessment: black and minority ethnic groups. In: Raftery J, Stevens A, Mant J, eds. Health care needs assessment. The epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews. 3rd series. Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing, 2007.

- 3.Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Perinatal mortality 2006: England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: CEMACH, 2008.

- 4.Department of Health. Tackling health inequalities: a programme for action. July 2003www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4008268 (accessed 12 March 2008).

- 5.Department of Health. Programme budgeting category 18—maternity and reproductive health. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Financeandplanning/Programmebudgeting/index.htm (accessed 12 March 2008

- 6.Department of Health. Health inequalities: revised list of spearhead group primary care trusts. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Dearcolleagueletters/DH_4138963 (accessed 12 March 2008).

- 7.National Centre for Health Outcomes Development (NCHOD). www.nchod.nhs.uk/ (accessed 12 June 2007).

- 8.Noble M, Wright G, Dibben C, Smith GAN, McLennan D, Anttila C, et al. Indices of deprivation 2004. Report to the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. London: Neighbourhood Renewal Unit, 2004.

- 9.Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Tutorial in biostatistics multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collett D. Modelling binary data. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, 2002.

- 11.MacArthur C, Jolly K, Ingram L, Freemantle N, Dennis C-L, Hamburger R, et al. Antenatal peer support workers and breastfeeding initiation: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TAJ, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008;372:1661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bundey S, Alam H, Kaur A, Mir S, Lancahire RJ. Why do UK-born Pakistani babies have high perinatal and neonatal mortality rates? Paediat Perinat Ep 1991;5:101-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad WIU. Reflections on the consanguinity and birth outcome debate. J Public Health Med 1994;16:423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alwan A, Modell B, Bittles, Czeizel A, Hamamy H. Community control of genetic and congenital disorders. Alexandria: World Health Organization, 1997.

- 16.Bakeo AC. Investigating variations in infant mortality in England and Wales by mother’s country of birth, 1983-2001. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2006;20:127-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy UM, Ko CW, Willinger M. Maternal age and risk of stillbirth throughout pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:764-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brambley P, Jackson A, Muir Gray JA. Better allocation for better health and heathcare: The first annual population review. NHS National Knowledge Service. February 2007.

- 19.Adam T, Lim SS, Mehta S, Bhutta ZA, Fogstad H, Mathai M, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. BMJ 2005;331:1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Bell R, Pearce MS, Parker L. Temporal changes in the distribution of population risk factors attenuate the reduction in perinatal mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:1299-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nixon J, Ulmann P. The relationship between health care expenditure and health outcomes: evidence and caveats for a causal link. Eur J Health Econom 2006;7:7-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelsey JL, Thompson WD, Evans AS. Methods in observational epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.