Abstract

Follow-up studies have been conducted every three years on the endemicity of Gymnophalloides seoi infection in a small coastal village of Chollanam-do (Province), Korea, since it was first known as an endemic area in 1994. Special attention was given to its egg laying capacity in the human host. In fecal examinations, the overall helminth egg and/or cyst positive rate was 78.7% (74/94) in 1997 and 76.6% (82/107) in 2000. Among them G. seoi eggs showed the highest rate; 71.3% (67/94) in 1997 and 72.0% (77/107) in 2000. The average number of eggs per gram of feces (EPG) was 1,015 in 1997, while a reduced rate of 353 was observed in 2000. In 1997, total of 320,677 adult flukes of G. seoi (av. 10,344/person, 94-69,125 in range) were collected from the diarrheic stools of 31 treated patients. The EPG/worm obtained from 21 cases ranged from 0.04 to 0.77 (av. 0.23), suggesting density-dependent constraints on the worm fecundity. The relationship between the worm burden (X) and EPG/worm (Y) can be expressed as Y=0.42 ·e-1.2χ (r=0.49). The results showed that G. seoi infection is persistently endemic in this village.

Keywords: Gymnophalloides seoi, egg laying capacity, human infection, prevalence, worm burden

INTRODUCTION

Gymnophalloides seoi Lee, Chai and Hong, 1993 (Digenea: Gymnophallidae) was described as a new human intestinal trematode obtained from a patient; the adult flukes were collected after anthelmintic treatment (Lee et al., 1993). The patient was suffering from acute pancreatitis and gastrointestinal troubles. Thereafter, its epidemiologic significance has grown remarkably, and a highly endemic area was discovered in the southwestern coastal island (Aphaedo) of Shinan-gun, Chollanam-do (Lee et al., 1994). This village was found to have 49% prevalence of G. seoi. Recently, five new human cases of G. seoi infection were found from other localities; three cases in the coastal village in Muan-gun, Chollanam-do (unpublished data) and two in the coastal village in Puan-gun, Chollabuk-do (Chai et al., 1998).

It has been verified that human infection with this fluke is contracted by eating raw oysters, Crassostrea gigas, produced naturally in the endemic area (Lee et al., 1995b). Most of oysters examined were infected with metacercariae of G. seoi, and the intensity of infection was the highest in Aphaedo (Island) in a nationwide oyster survey (Lee et al., 1996).

Therefore, with reasons depicted above, a special attention has been paid to G. seoi as a new human intestinal trematode. However, it still remains to be determined whether the high prevalence and endemicity of G. seoi infection is merely a temporary event or the endemicity is maintained continuously under natural conditions.

In order to answer to this question, we performed follow-up studies on the status of G. seoi infection, including symptoms complained by infected individuals, and their food habits, in the known endemic village of Aphaedo (Island) (Lee et al., 1994). In addition, as the reproducibility of G. seoi in the human host is yet unknown, the egg laying capacity in terms of the EPG/worm (eggs per gram of feces/worm) and EPD/worm (eggs per day/worm) was estimated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The surveyed area was a small coastal village located in Aphaedo (Island), Shinan-gun, Chollanam-do, Korea, and the location is known as an endemic area for G. seoi (Lee et al., 1994). The first and second follow-up surveys were performed in August 1997 and in January 2000, respectively, in the same village. In each survey, mass treatments were undertaken with 10 mg/kg single dose of praziquantel on the whole villagers.

Fecal specimens were collected from 94 (1997) and 107 people (2000) including both sexes and all age groups, and they were examined by formalin-ether sedimentation and cellophane thick smear techniques. Individuals found infected with G. seoi in 1997 were treated with 10 mg/kg single dose of praziquantel followed by purgation with 20-30 g magnesium sulfate (MgSO4). After washing the stools several times with tap water, the flukes were recovered from each patient with the aid of stereomicroscope. The worms were fixed in 10% formalin and the number of worms were counted. Some of the fixed specimens were stained with Semichon's acetocarmine for morphological identification.

To estimate the egg laying capacity of G. seoi in the human host, the EPG/worm and EPD/worm were calculated. To obtain the EPG/worm, the fecal EPG of each case was counted on the cellophane smears and divided by the number of worms recovered after treatment. The EPD/worm was calculated by multiplying the EPG/worm and the average weight (200 g) of the daily stool output (Seo et al., 1985).

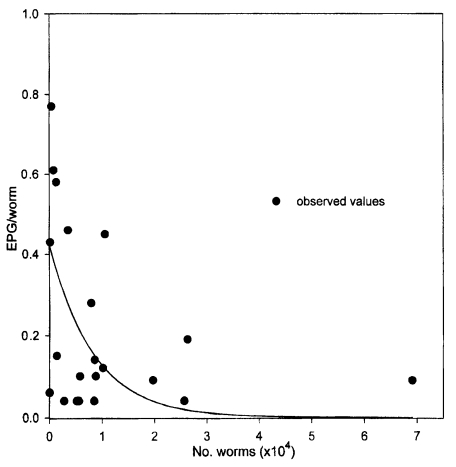

Obtained figures of the EPG/worm varied greatly case by case (Table 4), but it seemed highly dependent upon the degree of individual worm burdens. Hence, it was taken into consideration that there would be density-dependent constraints in the worm fecundity, as reported in infections with nematodes such as Ascaris lumbricoides (Anderson and May, 1982) and trematodes such as Metagonimus yokogawai (Seo et al., 1985). For analysis of such phenomenon, equations applicable to express the relations between the worm burden (X) and worm fecundity (Y) were introduced; Y=a · Xb or Y=a · e-bx, where 'a' and 'b' are constants determining the degree of constraints (Anderson and May, 1982). Using the latter equation, a regression curve best fit to the observed values was drawn and theoretical values of the EPG/worm and EPD/worm were calculated.

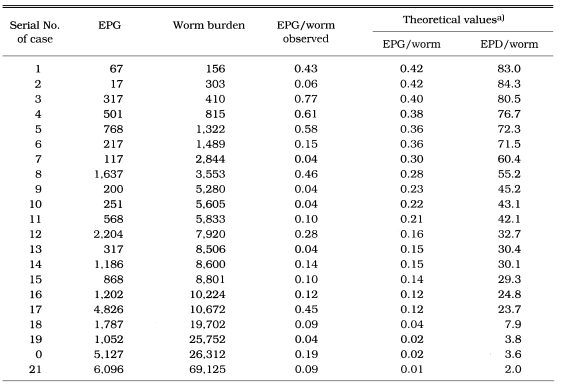

Table 4.

The relationship between EPG, worm burden and theoretical values for the egg-laying capacity of Gymnophalloides seoi in 21 inhabitants

a)From equation Y=0.42 · e-1.2χ (r=0.49), where X is the worm burden and Y is the EPG/worm (observed and theoretical value; p>0.1)

In order to evaluate the symptoms complained by G. seoi-infected persons and to determine their food habits, a questionnaire study was performed on the villagers in 1997. In addition, to find any relationship of G. seoi infection with diabetes mellitus, the blood and urine glucose levels were examined.

The chi-square test was performed to evaluate the significance of different values obtained from each group. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

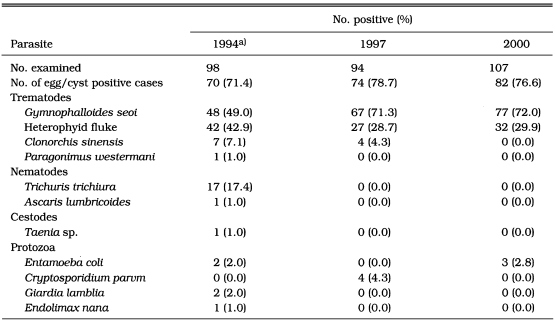

The overall egg and/or cyst positive rate of intestinal parasites among inhabitants was 78.7% in 1997 and 76.6% in 2000 (Table 1). The egg positive rate of G. seoi was the highest of all species of parasites detected; 71.3% (67/94) in 1997, and 72.0% (77/107) in 2000. Although mass treatment with praziquantel was carried out on the whole inhabitants in 1997, the egg positive rate of G. seoi in 2000 returned back to the same level as observed in 1997. The majority of other helminth eggs detected was heterophyid eggs; 28.7% (27/94) in 1997, and 29.9% (32/107) in 2000 (Table 1). Twenty-four cases (25.5%) in 1997, and 29 cases (27.0%) in 2000, were infected with more than two species of parasites.

Table 1.

Prevalence of egg and/or cyst positive rate by fecal examination among the inhabitants in a small village on Aphaedo (Island), Chollanam-do (1994, 1997 and 2000)

a)reported by Lee et al. (1994).

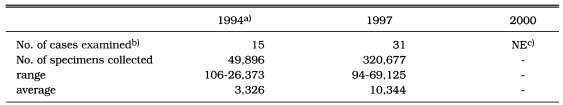

The measurement of individual worm burdens (minimum confirmed number) was completed in 31 G. seoi-infected cases who cooperated in the anthelmintic treatment and purgation in 1997. The number of G. seoi specimens collected from each case was in the range 94-69,125, with an average of 10,344 worms per infected case (Table 2). From stained specimens, they were identified as Gymnophalloides seoi Lee, Chai and Hong, 1993. Other flukes collected were mainly Heterophyes nocens and other heterophyids (data not shown).

Table 2.

Comparison of the number of flukes collected from Gymnophalloides seoi egg positive cases after praziquantel treatment in a small village on Aphaedo (Island), Chollanam-do

a)reported by Lee et al. (1994).

b)Statistical test revealed significant differences (p<0.005) between 1994 and 1997 in the number of worms collected.

c)not examined.

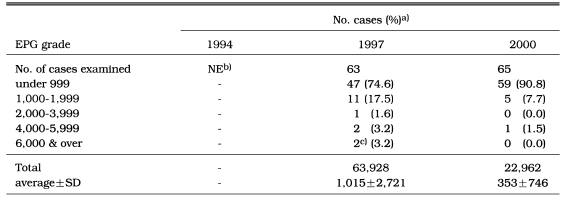

In 1997, the total sum of the EPG of G. seoi was 63,928 among 63 egg positive cases, with an average of 1,015 per case and standard deviation (SD) of 2,721. In 2000, the total sum of G. seoi EPG was 22,962 among 65 egg positive cases, with an average of 353 per case and SD of 746 (Table 3). The average EPG in 2000 was significantly lower than that in 1997 (p<0.005). The number of cases with EPG lower than 1,000 was higher in 2000 than that in 1997 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of EPG grade in egg positive cases of Gymnophalloides seoi

a)Statistical test revealed significant differences (p<0.005) between 1997 and 2000 in EPG.

b)not examined.

c)EPG of these cases were 6,095 and 20,140, respectively.

The cases treated and successfully checked their worm burdens consisted of 21 people, in whom the EPG ranged 17-6,096 (Table 4). The lowest worm burden was 156 with EPG of 67. Six cases expelled more than 10,000 worms, three of them expelled more than 20,000 worms, and the highest number of worms recovered was 69,125. Thereby, the EPG/worm in 21 cases was calculated as 0.04-0.77 (av. 0.23), showing a big individual variation (Table 4).

By observing and plotting the individual worm burden (X) and worm fecundity (Y), the equation Y=a · e-bx was selected as the appropriate function. The correlation equation obtained was Y=0.42 · e-1.2χ (r=0.49) (Fig. 1). Based on this equation, the theoretical values of the EPG/worm and EPD/worm were in the range, 0.01-0.42 and 2.0-84.3, respectively (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

The density-dependent constraints on the fecundity of Gymnophalloides seoi in the studied human population (Y=0.42e-1.2χ where 'X' is the worm burden and 'Y' is the EPG/worm).

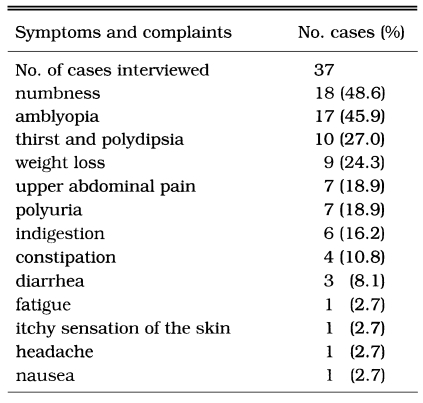

Clinical symptoms complained by cases infected with G. seoi included numbness, amblyopia, thirst, polydipsia, weight loss, epigastric and abdominal pain, polyuria, indigestion, constipation, and diarrhea (Table 5). About a half (43.2%) of G. seoi-infected cases experienced gastrointestinal symptoms, and another half (45.8%) had symptoms such as thirst, polydipsia, and polyuria, that may occur in patients with diabetes mellitus. Their blood and urine glucose levels were, however, within normal limits (data not shown).

Table 5.

Symptoms and complaints of cases infected with Gymnophalloides seoi in a coastal village on Aphaedo (Island), Chollanam-do (1997)

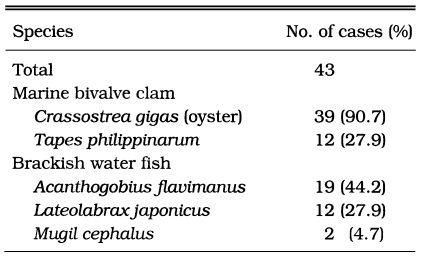

The inhabitants infected with G. seoi, the majority of whom were infected simultaneously with heterophyid flukes, stated in the questionnaires that they consumed oysters, marine clams, and brackish water fishes (Table 6). Out of 43 cases infected with G. seoi, 39 (90.7%) had the history of eating raw oysters.

Table 6.

Results of a questionnaire study on food ingestion by cases infected with Gymnophalloides seoi in a small coastal village on Aphaedo (Island), Chollanam-do

DISCUSSION

The egg positive rate of G. seoi and individual worm burdens were surprisingly high in two repeated examinations (1997 and 2000), representing persistent endemicity of this fluke in the surveyed village. With respect to the egg positive rate, the rates of 71.3% in 1997 and 72.0% in 2000 were rather high when compared to the previously reported rate of 49.0% in the same village (Lee et al., 1994). As for the individual worm burdens, the observed values (minimum confirmed number) in 1997 were 10,344 worms/case and 94-69,124 in range which were also significantly (p<0.005) higher than the previous figures of 3,326 worms/case and 106-26,373 in range in 1994 (Table 2).

Such heavy infections with G. seoi must have been undoubtedly caused by frequent and repeated consumption of raw oysters which are known to cause infection. The intensity of G. seoi infection in oysters produced nearby the endemic village was as many as 785.9 metacercariae on average (Lee et al., 1995b). Therefore, just several oysters being eaten raw, infection with more than 1,000 worms could be possible in the people living in this village. It is strongly suggested that the high intensity of metacercarial infection in oysters, together with their eating habits favoring the consumption of raw oysters, could be responsible for the persistence of G. seoi endemicity in this coastal village.

Since oysters are produced not only from this area but also from other seashore areas, and since they are favored raw by many local people in Korea, human G. seoi infection may not be confined only to the subjected area (Lee et al., 1994). However, based on the fecal examination of the villagers and the results of oyster surveys, only low levels of endemicity were recognized in different localities such as Muan-gun, Chollanam-do (Province) and Puan-gun, Chollabuk-do (Province) (Chai et al., 1998).

In general, the egg laying capacity of trematodes is lower than that of nematodes. For example, the egg laying capacity of A. lumbricoides in the human host is known to be 90,000-280,000 eggs per day per mature female (Chai et al., 1981). On the other hand, Clonorchis sinensis lay much smaller number of eggs, 360 eggs per day per worm in experimental rats (Seo, 1958) and probably a little more in the human host. In the case of small intestinal trematodes, the capacity is much lower than that of C. sinensis. For example, the daily number of eggs produced per worm of M. yokogawai was estimated at about 14-64 eggs in the human host, showing significant density-dependent constraints on the worm fecundity (Seo et al., 1985). In the present study, the daily egg laying capacity of G. seoi was estimated at about 2-84 per worm, and stronger density-dependent constraints were recognized.

Such a low egg laying capacity of G. seoi or M. yokogawai (Chai and Lee, 1990) makes the detection of eggs in fecal examinations very difficult. Unless more than 100 worms are infected in a person, less than 8,400 eggs would be present in the whole-day stool at most with the value of EPG being about 42 (daily stool weight; 200 g). This value means the appearance of only 1-2 eggs on the whole field of a fecal smear made by the Kato-Katz technique (41.7 mg of feces/smear). The eggs of G. seoi are more difficult to detect than those of M. yokogawai because the former has smaller egg size with very thin and transparent shell, hence, could be easily overlooked even by an experienced examiner.

It is worthwhile to note that, based on a questionnaire study, about a half of the G. seoi-infected persons recalled that they experienced variable degrees of gastrointestinal troubles including indigestion, abdominal pain and diarrhea. However, the degree of symptoms was not necessarily correlated with the level of individual worm burdens. It is speculated that acquired partially protective immunity as to reduce symptoms only may develop due to repeated infections for a long time in the endemic area.

Two interesting cases of G. seoi infection accompanied by diabetes mellitus were reported, and some relations between the two kinds of diseases were suspected (Lee et al., 1995a). In the present study, 17 (45.9%) of 37 G. seoi-infected cases complained of thirst, polydipsia and polyuria, which may occur in patients with diabetes mellitus. However, their blood and urine did not show any increased levels of glucose. Non-specific symptoms such as numbness and amblyopia probably due to aging were also complained by many of the G. seoi-infected persons.

In conclusion, the present study confirmed that G. seoi infection is persistently prevalent and endemic in the surveyed coastal village in Aphaedo (Island), showing rather increased egg positive rates and increased individual worm burdens than in the previous study (Lee et al., 1994). The egg laying capacity of G. seoi is estimated relatively low in the human host, and the density-dependent constraints in the worm fecundity are suggested to occur in the infected cases with this fluke.

Footnotes

This study was supported in part by a grant No. 02-1997-231 from Seoul National University Hospital Research Fund (1997).

References

- 1.Anderson RM, May RM. Population dynamics of human helminth infections: control by chemotherapy. Nature. 1982;297:557–563. doi: 10.1038/297557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chai JY, Hong ST, Lee SH, Seo BS. Fluctuation of the egg production amounts according to worm burden and length of Ascaris lumbricoides. Korean J Parasitol. 1981;19:38–44. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1981.19.1.38. (in Korean) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chai JY, Lee SH. Intestinal trematodes of humans in Korea: Metagonimus, heterophyids and echinostomes. Korean J Parasitol. 1990;28(suppl):103–122. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1990.28.suppl.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai JY, Song TS, Han ET, Guk SM, Park YK, Choi MH, Lee SH. Two endemic foci of heterophyids and other intestinal fluke infections in southern and western coastal areas in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1998;36:155–161. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1998.36.3.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SH, Chai JY, Hong ST. Gymnophalloides seoi n. sp. (Digenea: Gymnophallidae), the first report of human infection by a gymnophallid. J Parasitol. 1993;79:677–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SH, Chai JY, Lee HJ, et al. High prevalence of Gymnophalloides seoi infection in a village on a southwestern island of the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:281–285. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SH, Chai JY, Seo M, Choi MH, Kim DC, Lee SK. Two cases of Gymnophalloides seoi infection accompanied by diabetes mellitus. Korean J Parasitol. 1995a;33:61–64. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1995.33.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SH, Choi MH, Seo M, Chai JY. Oysters, Crassostrea gigas, as the second intermediate host of Gymnophalloides seoi (Gymnophallidae) Korean J Parasitol. 1995b;33:1–7. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1995.33.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SH, Sohn WM, Hong SJ, Hun S, Seo M, Choi MH, Chai JY. A nationwide survey of naturally produced oysters for infection with Gymnophalloides seoi metacercariae. Korean J Parasitol. 1996;34:107–112. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1996.34.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo BS. Studies on the egg laying capacity and development of Clonorchis sinensis in albino rats. Seoul Nat Univ J (Nat Sci Ser C) 1958;7:1–15. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo BS, Lee HS, Chai JY, Lee SH. Intensity of Metagonimus yokogawai infection among inhabitants in Tamjin river basin with reference to its egg laying capacity in human host. Seoul J Med. 1985;26:207–212. [Google Scholar]