Abstract

The sequences of activation and recovery of the heart have physiological and clinical relevance. We report on progress made over the last years in the method that images these timings based on an equivalent double layer on the myocardial surface serving as the equivalent source of cardiac activity, with local transmembrane potentials (TMP) acting as their strength. The TMP wave forms were described analytically by timing parameters, found by minimizing the difference between observed body surface potentials and those based on the source description. The parameter estimation procedure involved is non-linear, and consequently requires the specification of initial estimates of its solution. Those of the timing of depolarization were based on the fastest route algorithm, taking into account properties of anisotropic propagation inside the myocardium. Those of recovery were based on electrotonic effects. Body surface potentials and individual geometry were recorded on: a healthy subject, a WPW patient and a Brugada patient during an Ajmaline provocation test. In all three cases, the inversely estimated timing agreed entirely with available physiological knowledge. The improvements to the inverse procedure made are attributed to our use of initial estimates based on the general electrophysiology of propagation. The quality of the results and the required computation time permit the application of this inverse procedure in a clinical setting.

Keywords: Fastest route algorithm, Non-invasive imaging, Activation, Recovery, Electrotonic interaction

Introduction

The sequence of activation and recovery of the heart, atria and ventricles, has physiological significance and clinical relevance. The standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), commonly used in diagnostic procedures, provides insufficient information for obtaining an accurate estimate of these sequences in all types of abnormality or disease.

Since the inception of electrocardiography12,49 several methods have been developed aimed at providing more information about cardiac electric activity on the basis of potentials observed on the body surface. The differences between these methods relate to the implied physical description of the equivalent generator representing the observed potential field. The earliest of these are the electric current dipole, a key element in vectorcardiography,3,14 and the multipole expansion.16 Neither of these source models offer a direct view on the timing of myocardial activation and recovery, or other electro-physiologically tinted features.

From the 1970s onwards, the potential of two other types of source descriptions have been explored.21,22 This development stemmed from increased insight in cardiac electrophysiology and advances in numerical methods and their implementation in ever more powerful computer systems. The results of both methods are scalar functions on a surface. The solving of the implied inverse problem may, accordingly, be viewed as a type of functional imaging, which has led to their characterization as, e.g., “Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI)”42 or “Myocardial Activation Imaging.”29 A brief characterization of both methods is as follows.

The first surface source model is that of the potential distribution on a closed surface closely surrounding the heart, somewhat like the pericardium, referred to here as the pericardial potential source (PPS) model. The model is based on the fact that, barring all modeling and instrumentation errors, a unique relation exists between the potentials on either of two nested surfaces, one being the body surface, the other the pericardium, provided that there are no active electric sources in the region in between. It was first proposed at Duke by Martin and Pilkington37; its potential has subsequently been developed by several other groups.4,5,20,23,46

The second type of surface source model evolved from the classic model of the double layer as an equivalent source of the currents generated at the cellular membrane during depolarization, described by Wilson et al.69 Initially, this current dipole layer model was used to describe the activity at the front of a depolarization wave propagating through the myocardium.11,50 Later, Salu47 expressed the equivalence between the double layer at the wave front and a uniform double layer at the depolarized part of the surface bounding the myocardium, based on solid angle theory.62 This source description has been explored by others.8,26,29,38,45

This paper reports on recent progress made in inverse procedures based on the second type of surface source model: the equivalent double layer on the heart’s surface as a model of the electric sources throughout the myocardium; we refer to it as the EDL model. In contrast with the PPS model, the EDL source model relates to the entire surface bounding the atrial or ventricular myocardium: epicardium, endocardium and their connection at the base. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the EDL was initially used for modeling the currents at the depolarizing wave front only. Based on the theory proposed by Geselowitz,17,18 it was found to be also highly effective for describing the cardiac generator during recovery (the repolarization phase of the myocytes). The transmembrane potentials (TMPs) of myocytes close to the heart’s surface act as the local source strength of the double layer. Several examples of its effectiveness in forward simulations have appeared in the literature.28,31,51,63 A striking example of the model’s potential in inverse procedures is seen in the paper by Modre et al.,39 an application dedicated to the atrial activation sequence.

In our application the TMPs’ wave forms were specified by an analytical function involving just two parameters, markers for the timing of local depolarization and repolarization. These parameters were found by using a standard parameter estimation method, minimizing the difference between observed body surface potentials (BSPs) and those based on the source description. Since the body surface potentials depend non-linearly on these parameters, a non-linear parameter estimation technique is required, which demands the specification of initial estimates. It is here that some novel elements are reported on, and a major part of the paper is devoted to their handling. The initial parameters for the timing of local depolarization were based on the fastest route algorithm, taking into account global properties of anisotropic propagation inside the myocardium. Those pertaining to recovery were based on electrotonic interaction as being the driving force for the spatial differences in the local activation-recovery interval. With the other elements of the method being similar to those used in previous work, the emphasis of the paper is on the description of the novel elements.

In the Methods section, the entire inverse procedure is described and a justification given of those model parameters that are treated as constants during the optimization procedure. In the Results section, examples of inverse estimated ventricular activation and recovery sequences are presented: those of a healthy subject, a WPW patient and a Brugada patient during an Ajmaline provocation test. The value, application and limitations of this approach are considered in the Discussion.

Materials

The results shown in this paper are based on data recorded in three subjects. The nature of this data is summarized below. More details can be found in previous publications,1,13,35,56 in which essentially the same material was used.

In each patient, a 64-lead ECG was recorded. For each subject, MRI-based geometry data was available from which individualized numerical volume conductor models were constructed, incorporating the major inhomogeneities in the conductive properties of the thorax, i.e., the lungs, the blood-filled cavities and the myocardium.

The first subject (NH) is a healthy subject.56 This subject was included to illustrate intermediate and final results of the described inverse procedure. The other two subjects are added to illustrate clinical applications.

The second subject (WPW) is a WPW patient for whom previously estimated activation times have been published.1,13 The recorded ECGs included episodes in which the QRS displayed the typical WPW pattern, i.e., a fusion beat in which the activation is initiated at both the AV node and the Kent bundle. The location of the latter was determined invasively. The ECGs were also recorded after an AV-nodal block had been induced by a bolus administration of adenosine, resulting in an activation sequence solely originating from the Kent bundle.

The third case was a Brugada patient in whom ECG data were recorded during infusion of a sodium channel blocker (Ajmaline),35 10 bolus infusions of 10 mg, administered at 1-min intervals,71 which changes the activation and/or recovery sequence. The beats selected for analysis were: the baseline beat 5 min prior to infusion and the beat after the last bolus had been administered.

For each subject, the number of nodes representing the numerical representation of the closed surface (endo-and epicardium) of the ventricles and the observed QRS durations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subjects for whom the ventricular depolarization and repolarization sequences were estimated

| Subject | Type | # Nodes on the heart’s surface | QRS duration ms |

|---|---|---|---|

| WPW | WPW patient | 697 | 119 (fusion beat) 159 (AV blocked) |

| BG | Brugada patient | 287 | 104 (baseline) 124 (peak infusion) |

| NH | Healthy subject | 1500 | 101 |

For subject WPW the fusion beat data and after the administration of adenosine to block the AV node. For subject BG the baseline beat data (first row) and after the last administration of Ajmaline are given

Methods

Local EDL Strength

The time course of the TMP acting as the local EDL source strength was specified by the product of three logistic functions, the functions of the type

|

1 |

describing a sigmoidal curve with maximum slope β/4 at t = τ.

The first of these functions described phase (0) of the TMP time course,33 the depolarization phase, as

|

2 |

with δ the timing of local depolarization and the factor β setting the steepness of the upstroke.

Local repolarization refers to the period during which the TMP moves toward its resting state (Phases 3 and 4), a process that may take up to some hundred ms. The TMP wave form during this period was described as

|

3 |

in which ρ sets the position of the inflection point of the TMPs down slope and β1 and β2 are constants setting its leading and trailing slope. Note that the action potential duration, α, defined as

|

4 |

represents the time interval between the marker used for the timing of local repolarization ρ and the timing of local depolarization δ; it may be interpreted as the activation recovery interval.24

In summary, the waveform specifying the strength  of the local EDL was

of the local EDL was

|

5 |

Note that this function depends on two parameters only. The constants β1 and β2 were found by fitting S(t; δ, ρ) to the STT segment of the rms(t) curve of the 64 ECGs of the individual subjects, as is described in van Oosterom63 and motivated in van Oosterom.61 Examples of the TMP wave forms obtained from (5) are shown in Fig. 1. These may be shifted in time as appropriate in individual cases. Moreover they may be scaled in amplitude to an arbitrary, uniform level in the application to non-ischemic tissue for which, based on solid angle theory applied to a closed double layer, a uniform strength produces no external field.

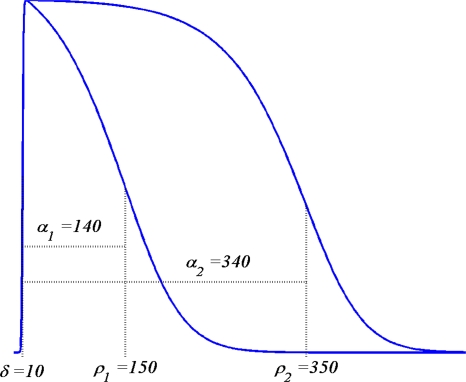

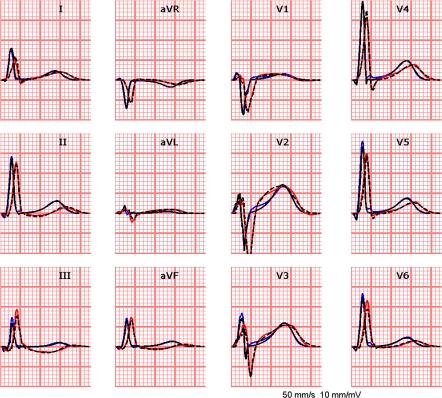

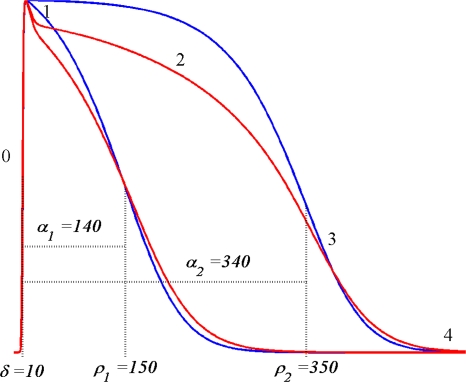

Figure 1.

Examples of TMP wave forms based on (5), The constants δ and ρ specify two different timings of activation and recovery; the corresponding activation recovery intervals are α = ρ − δ

Computing Body Surface Potentials

Based on the EDL source description, with its local strength at position  on the surface of the ventricular myocardium (Sv) taken to be the local transmembrane potential

on the surface of the ventricular myocardium (Sv) taken to be the local transmembrane potential  , the potential

, the potential  generated at any location

generated at any location  on the body surface is

on the body surface is

|

6 |

in which  is the solid angle subtended at

is the solid angle subtended at  by the surface element

by the surface element  of Sv and

of Sv and  is the transfer function expressing the full complexity of the volume conductor (geometry and tissue conductivity). Previous studies26,59 indicated that an appropriate volume conductor model requires the incorporation of the heart, blood cavities, lungs and thorax. In this study, the conductivity values σ assigned to the individual compartments were: thorax and ventricular muscle: 0.2 S/m, lungs: 0.04 S/m and blood cavities: 0.6 S/m.

is the transfer function expressing the full complexity of the volume conductor (geometry and tissue conductivity). Previous studies26,59 indicated that an appropriate volume conductor model requires the incorporation of the heart, blood cavities, lungs and thorax. In this study, the conductivity values σ assigned to the individual compartments were: thorax and ventricular muscle: 0.2 S/m, lungs: 0.04 S/m and blood cavities: 0.6 S/m.

The complex shape of the individual compartments within the volume conductor model does not permit one to determine  by means of an analytical method. Instead, numerical methods have to be used. In this study we used the boundary element method (BEM).21,58 By means of this, while using (5) for describing the TMP, the potential at any node ℓ of the discretized (triangulated) body surface was computed as

by means of an analytical method. Instead, numerical methods have to be used. In this study we used the boundary element method (BEM).21,58 By means of this, while using (5) for describing the TMP, the potential at any node ℓ of the discretized (triangulated) body surface was computed as

|

7 |

with n the number of nodes of the triangulated version of Sv. For each moment in time this amounts to the pre-multiplication of the instantaneous column vector (source) S by a (transfer) matrix B, which incorporates the solid angles subtended by source elements as viewed from the nodes of the triangulated surface, scaled by the relative jump in  of the local conductivity values σ+i and σ−i at either sides of the interfaces i considered.21,58

of the local conductivity values σ+i and σ−i at either sides of the interfaces i considered.21,58

Inverse Computation of Activation and Recovery

The timing of local depolarization and repolarization was treated as a parameter estimation problem, carried out by minimizing in the least squares sense with respect to the parameters δ and ρ, the difference between the potentials computed on the basis of (7) and the corresponding body surface potentials V(t, ℓ) observed in the subjects studied. Since the source strength depends non-linearly on the parameters, the minimization procedure needs to be carried out iteratively, for which we used a dedicated version of the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm.36 The subsequent steps of this procedure alternated between updating the δ and ρ estimates. Updating δ was carried out on the basis of solving

|

8 |

Matrix L represents a numerical form of the surface Laplacian operator,27 which serves to regularize the solution by guarding its (spatial) smoothness, μ2 its weight26 in the optimization process and  the square of the Frobenius norm. Matrix L is the Laplacian operator normalized by the surface.26 Consequently Lδ is proportional to the reciprocal of the propagation velocity. As the propagation velocity of activation and recovery are in the same order of magnitude the same value for μ can be used for activation and recovery.

the square of the Frobenius norm. Matrix L is the Laplacian operator normalized by the surface.26 Consequently Lδ is proportional to the reciprocal of the propagation velocity. As the propagation velocity of activation and recovery are in the same order of magnitude the same value for μ can be used for activation and recovery.

Updating ρ was based on the same expression after interchanging δ and ρ in the regularization operator (latter part of (8)). Since the problem in hand is non-linear, initial estimates are required for both. In previous studies, related to the activation sequence (δ) only, the initial estimates involved were derived exclusively from the observed BSPs.8,26,38,45 The method employed here is based on the general properties of a propagating wave front. From this initial estimate for depolarization, an estimate of the initial values of the repolarization marker, ρ, is worked out by including the effect of electrotonic interaction on the repolarization process.

The Initial Estimate of the Timing of Activation

During activation of the myocardium, current flows from the intracellular space of the depolarized myocytes to the intracellular space of any of its neighbors that are still at rest (polarized at their resting potential). The activation of the latter takes about 1 ms and is confined to about 2 mm. The boundary of this region (the activation wave front) propagates toward the tissue at rest until all of the myocardium has been activated. The propagation can be likened to the Huygens process. The local wave front propagates in directions dominated by the orientation of local fibers, at velocities ranging from 0.3 m/s across fibers to 1 m/s along fibers. Under normal circumstances, ventricular depolarization originates from the bundle of His, progresses through the Purkinje system, from which the myocardium is activated.57 In humans this Purkinje system is mainly located on the lower 2/3 of the endocardial wall.9,40 In other cases, ventricular activation originates from an ectopic focus or from a combination of the activity of the His-Purkinje system and an ectopic focus. The initial estimate of the inverse procedure was based on the identification of one or more sites of initial activation, from which activation propagates. This includes normal activation of the myocardium, which can be interpreted as originating from several foci representing the endpoints of the Purkinje system. The activation sequence resulting from a single focus was derived by using the fastest route algorithm.

The Fastest Route Algorithm

The fastest route algorithm (FRA) determines the fastest route between any pair of nodes of a fully connected graph.70 The term ‘fully connected’ signifies that all nodes of the graph may be reached from any of the other ones by traveling along line segments, called edges, that directly connect pairs of nodes. In the current application the term edges not only refers to the edges of the triangles constituting the numerical representation of Sv, but also to the paths connecting epicardial and endocardial nodes,66 provided that the straight line connecting them lies entirely within the interior of Sv.

The structure of the graph is represented by the so-called adjacency matrix, A, which has elements ai,j = 1 if nodes i and j are connected by an edge, otherwise ai,j = 0. By specifying velocity vi,j for every edge (i,j), i.e., for every non-zero element of A, the travel time ti,j along the edge is

|

9 |

in which di,j is the distance along the edge.

Edge Velocities

In the MRI based geometry of the ventricles the node distances di,j are known. In the application of (9), the velocities along the edges need to be specified. For want of proper estimates on the myocardial penetration sites of the Purkinje system of the individual subjects, as will be case in the ultimate, clinical application of the proposed method, relatively crude edge velocity estimates were used. Values reported for the anisotropy ratio vℓ/vt of longitudinal and transverse-fiber velocities show a wide range: from 2 to 6.34,43,48,52

In this study two related velocities were used: the velocity in directions along the ventricular surface and the one in directions normal to the local surface, vℓ and vt, respectively. Their ratio was taken to be 2, the lower end of the range, selected in order to account for transmural rotation of the fibers.54 For transmural edges that were not normal to the local surface, the travel time ti,j was taken to be

|

10 |

with d and h the lengths of the projections of the edge along Sv and normal to it, respectively. This procedure approximates locally elliptical wave fronts. The factor 4 appearing on the right in (10) results from the assumed anisotropy ratio 2. Infinite travel times are assigned to pairs (i,j) that are not connected by an edge. The entire set of ti,j constitutes a square, symmetric matrix AT, on the basis of which the FRA computes the shortest travel time between arbitrary node pairs. The results form a square, symmetric travel time matrix T.

The Initial Activation Estimate: Multi-Foci Search

The element j of any row i of matrix T was interpreted as the activation time at node j resulting from focal activity at node i only. A search algorithm was designed, aimed at identifying one focus, or a number of foci, which identified the activation sequence yielding simulated body surface potentials that most closely resemble the recorded ones. If a focus at node i is taken to be activated at time ti, the other nodes will be depolarized at δj = ti + ti,j. If multiple foci are considered, the activation sequence is computed by the “first come, first served” principle: if K foci are involved, the depolarization time δj is taken to be

|

11 |

As is shown on the righthand side of (10), vℓ scales the elements of T, and consequently of δ. At each step the intermediate activation sequence, δ, vℓ was approximated by max(δ)/TQRS, with TQRS the QRS duration (see Table 1). For nodes known to represent myocardial tissue without Purkinje fibers the maximum velocity was set at 0.8 m/s. No maximum velocity was defined for nodes in a region potentially containing Purkinje fibers, the nodes in the lower 2/3 of the endocardial surfaces of the left and right ventricles.

For any activation sequence δ tested, ECGs were computed from (7) at each of the 65 electrode positions (64 lead signals + reference). Note that, with pre-computed matrices B and T, this requires merely the multiplication of the source vector by matrix B. The linear correlation coefficient R between all elements of the simulated data matrix Φ and those of the matrix of the measured ECGs, V, was taken as a measure for the suitability of δ for serving as an initial estimate. The lead signals were restricted to those pertaining to the QRS interval (about 100 samples spaced at 1 ms).

When taking a single node i of the N nodes on Sv as a focus, this results in N basic activation sequences δi, i = 1,…,N, and corresponding values Ri. The node exhibiting the maximum R value was selected as a focus.

The entire procedure was carried out iteratively. During the first iteration, the value ti = 0 was used, corresponding to the timing of onset QRS. In any subsequent iteration k, the accepted values for ti were set at 90% of their activation times found from the previous iteration. For the nodes corresponding to the above described ‘Purkinje system’ the values for ti were set at 40% of the previous activation times. The Purkinje systems is largely insulated from the myocardial tissue. The propagation velocity in this system ranges between 2 and 4 m/s. The 40% value of ti represents a 2.5 times higher velocity than the one used in the previous activation sequence, which is usually around 1 m/s. Within the myocardium the differences in velocity are much smaller, limited to approximately 0.7–1 m/s.

Note that a focus can be selected more than once, in which case its activation time decreases. The iteration process, identifying a focus at each step, was continued until the observed maximum value of R decreased.

The Initial Estimate of the Timing of Recovery

Background

In contrast to the situation during the activation of the myocardium, local recovery may take up to some hundred ms, while the repolarization process starts almost directly after the local depolarization. Similar to the situation during activation, throughout the recovery period current flows from the myocytes to their neighbors. The spatial distribution of these currents is not confined to some “repolarization” boundary, but instead is present throughout all regions that are “recovering”. Even so, some measure of the timing of local recovery at node n can be introduced, such as the marker ρn introduced previously, and its distribution over Sv can be used to quantify the timing of the overall recovery process.

The intracellular current flowing toward a myocyte is positive when originating from neighbors that are at a less advance state of recovery, thus retarding the local repolarization stemming from ion kinetics. Conversely, the current flows away when originating from neighbors at a more advanced stage of recovery, thus advancing local repolarization. The size of the two domains determines the balance of these currents, and thus the magnitude of the electrotonic interaction. At a site where depolarization is initiated, the balance is positive, resulting locally in longer action potential durations than those at locations where depolarization ends. The extent of the two domains is determined by the location of the initial sites of depolarization and overall tissue geometry.65 As a consequence, local action potential duration, α, is a function of the timing of local depolarization and, expressed in the notation of (4), so is ρ(δ) = δ + α(δ). Literature reports on the nature of the function α(δ) as observed through invasive measurements are scarce. In some reports7,15 a linear function was suggested, for which a slope of −1.32 was reported. The function used in our study involved the subtraction of two exponential functions. For small distances between a local depolarization (its source) and local ending of activation (its sink) this function becomes linear in approximation.65

The Initial Recovery Estimate

The initial estimate for ρ was found from ρ(δ) = δ + α(δ), with δ the initial estimate of the timing of depolarization. The value of αn at any node n was computed as

|

12 |

with  expressing the mean activation recovery interval,

expressing the mean activation recovery interval,  the difference between the depolarization times of the closest sink and source,

the difference between the depolarization times of the closest sink and source,  and ξ a dimensionless shape constant.65 Sources and sinks of activation were identified as nodes of Sv for which all neighbors in a surrounding region of 2 cm were activated earlier or later, respectively.

and ξ a dimensionless shape constant.65 Sources and sinks of activation were identified as nodes of Sv for which all neighbors in a surrounding region of 2 cm were activated earlier or later, respectively.

If more than one source and sink was found within a distance of 4 cm, the average value of the parameters xn and κn was assigned to the node n involved. The value of  was found through lining up

was found through lining up  with the apex of the rms(t) signal of the observed ECG signals.64

with the apex of the rms(t) signal of the observed ECG signals.64

Quality Measures

The differences between simulated and recorded potential data are quantified by using the rd measure: the root mean square value of all matrix elements involved relative to those of the recorded data. In addition, the linear correlation coefficient R between all elements of simulated and reference data is used.

Results

For all three cases, the activation and recovery sequences as found by means of the inverse procedure are presented. Some intermediate results pertaining to the healthy subject are included.

Healthy Subject

For all three cases considered, the weight parameter of the regularization operator, μ (see (8)), was empirically determined and set to 1.5 × 10−4, both while optimizing activation and recovery.

The upstroke slope, β (see (1)), was set to 2, resulting in an upstroke slope of 50 mV/ms. The parameter ξ (12) was tuned such that, for the healthy subject (NH), the linear slope of α(δ) was −1.32 (see Franz et al.15). This resulted in a value of 7.9 × 10−3 for ξ.

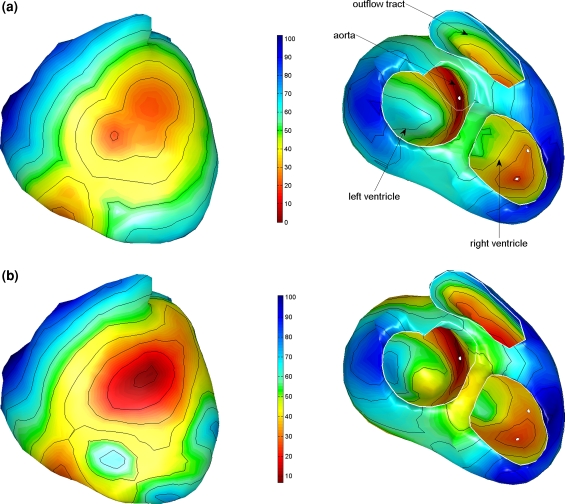

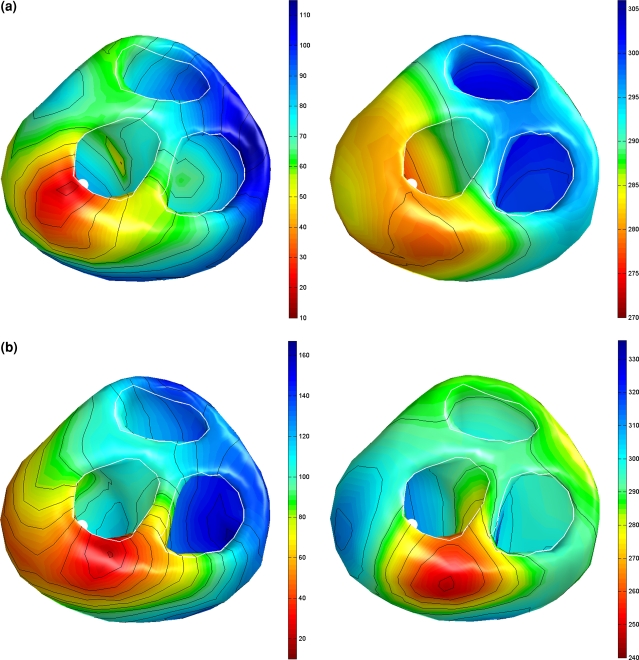

The initial activation estimated by means of the focal search algorithm is shown in Fig. 2a. In total 7 foci were found in four regions, the first one in the mid-left septal wall, the next on the lower right septal wall and some additional ones on the left and right lateral wall. The result obtained from the non-linear optimization procedure based on this initial estimate is shown in Fig. 2b.

Figure 2.

Estimated activation sequences of the ventricles of a healthy subject. (a) The initial estimate resulting from the multi-focal search algorithm; the white dots indicate some of the foci that were identified. (b) The result of the subsequently applied non-linear optimization procedure. Isochrones are drawn at 10 ms intervals. The ventricles are shown in a frontal view (left) and basal view (right)

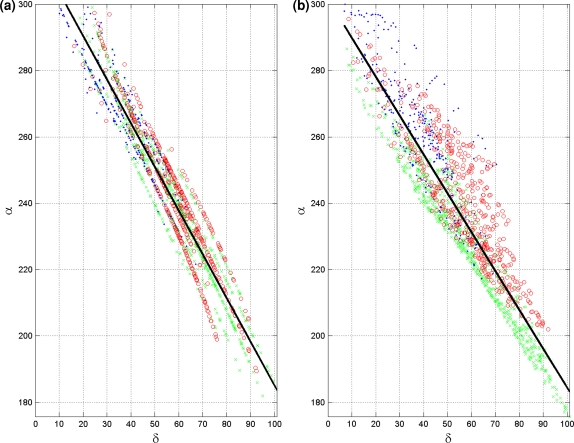

The initial estimated activation recovery intervals (ARI), derived from the initial activation sequence (Fig. 2a) and the use of Eq. (12) are shown in Fig. 3a. Note that areas activated early indeed have a longer ARI than the areas activated late. After optimization (Fig. 3b) the global pattern is similar to the initial one, with a minimally reduced range (from 182–320 ms to 176–300, see also Table 3). This can also be observed in Fig. 4, in which the local initial and final ARI values are plotted as a function of activation time. Consequently, the accompanying reduction in the linear regression slope between initial and estimated ARIs and activation times is also smaller (Table 3). The average of the estimated ARIs is 7 ms shorter than the initial ARIs. In general the estimated ARI values in the right ventricle shorten more compared to the initial estimate whereas the ARI values in the left ventricle and septum prolong slightly (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Estimated activation recovery intervals at the ventricular surface of a healthy subject. Initial and final ARIs as generated in the inverse procedure. (a) The initial ARI estimate. (b) The ARI distribution after optimization. Remaining legend as in Fig. 2

Table 3.

The range of ARI (α), repolarization times (ρ) and the slope of the linear regression between ARI and depolarization times (δ)

| Subject | (Initial) Slope (mV/ms) | Range α (ms) | Range ρ (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH | (−1.32) −1.17 | 176–300 (124) | 275–324 (49) |

| WPW | |||

| Fusion | (−1.21) −0.83 | 168–263 (95) | 271–306 (35) |

| AV blocked | (−1.08) −0.93 | 119–268 (149) | 248–336 (88) |

| BG | |||

| Baseline | (−1.27) −1.12 | 182–297 (116) | 244–317 (73) |

| Peak infusion | (−1.26) −0.92 | 108–302 (193) | 183–358 (174) |

All values shown relate to the final solution

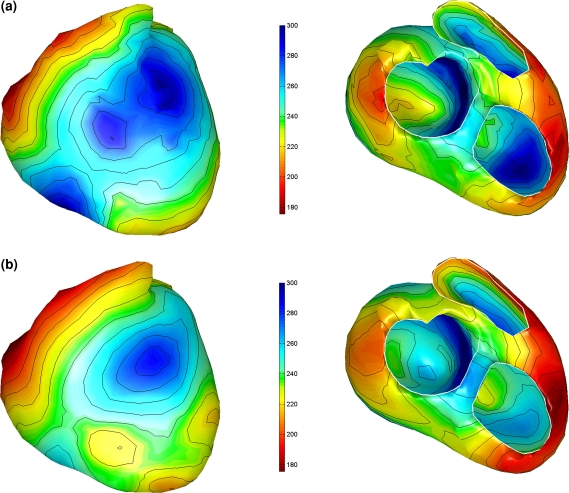

Figure 4.

Initial and final ARIs as generated in the inverse procedure. Initial estimation of the ARIs (a) and final estimated ARIs (b) as a function of the respective depolarization sequence. The solid black line indicates the linear regression line. Three areas within the heart have been identified by different markers, right ventricle (green), left ventricle (red) and (left and right) septum (blue)

The resulting recovery times show very little dispersion (49 ms, Table 3). The right ventricle starts to repolarize first, whereas the (left) septum repolarizes last (Fig. 5). Both the left and right ventricle show a prevailing epi- to endocardial direction of recovery.

Figure 5.

Recovery sequence as obtained from the inverse procedure. Remaining legend as in Fig. 2

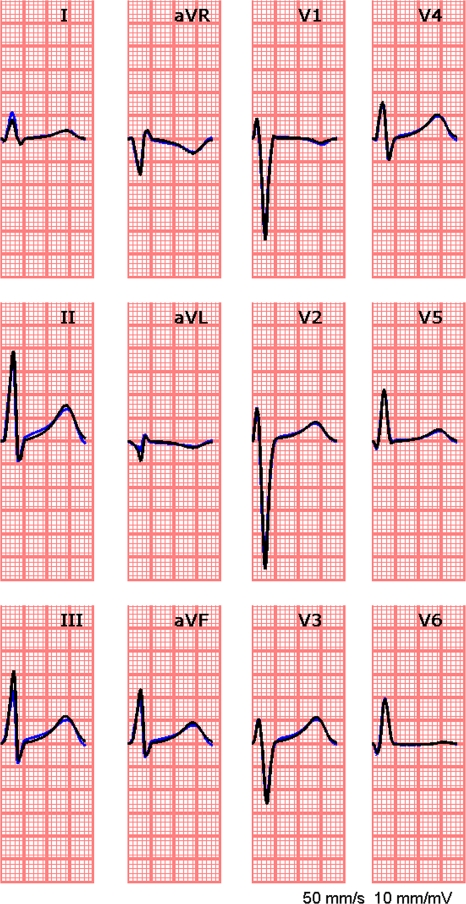

The measured ECGs and the simulated ECGs based on the estimated activation and recovery times, match very well during both the QRS and the STT segment (see Fig. 6), as indicated by the small rd value (0.12, Table 2).

Figure 6.

Standard 12-lead ECG; in blue: the measured data; in black: in black the simulated ECG based on the estimated activation and recovery times

Table 2.

R and rd values of the 3 subjects, computed over the segments indicated, pertaining to the initial estimate (focal search) and the final solution

| Subject | Initial activation (QRS segment only) | Initial recovery (QRST segment) | Activation & recovery (QRST segment) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rd | Correlation | rd | Correlation | rd | Correlation | |

| NH | 0.69 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.12 | 0.99 |

| WPW | ||||||

| Fusion | 2.46 | 0.87 | 2.39 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 0.98 |

| AV blocked | 1.72 | 0.86 | 2.39 | 0.84 | 0.17 | 0.99 |

| BG | ||||||

| Baseline | 1.41 | 0.89 | 1.31 | 0.82 | 0.15 | 0.99 |

| Peak infusion | 1.84 | 0.84 | 2.20 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.99 |

Fusion Beat with Kent Bundle

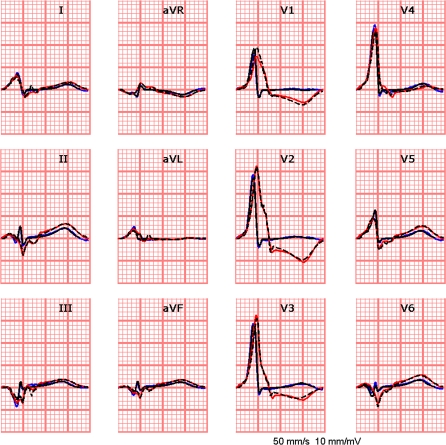

For the fusion beat the first focus identified by the focal search algorithm was the Kent bundle (Fig. 7a; see Fisher et al.13) subsequently 3 focal areas were determined: one on the lower left septal area and two on the right ventricular wall. The estimated repolarization times have a small dispersion (32 ms, see Fig. 7b), which is in agreement with the fact that the heart is activated from both the Kent Bundle and the His-Purkinje system.

Figure 7.

The results of the inverse procedure for a fusion beat, i.e., activation initiated by a Kent bundle and the His-Purkinje system (a) and for a Kent-bundle-only beat (b). The estimated activation sequences are shown on the left, the recovery sequences on the right. The white dot indicates the position of the Kent bundle as observed invasively. Remaining legend as in Fig. 2

For the beat in which the AV node was blocked a single focus was found at approximately the same location where the Kent bundle was found on the basis of the fusion beat. The resulting ECGs of both beats is shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8.

The simulated (black lines) and measured (blue lines) ECGs for a fusion beat (blue lines), i.e., activation initiated by both a Kent bundle and the His-Purkinje system, and the simulated (black lines) and measured (red lines) ECGs of a beat for which the AV node was blocked by adenosine, leaving only the Kent bundle intact

Brugada Patient

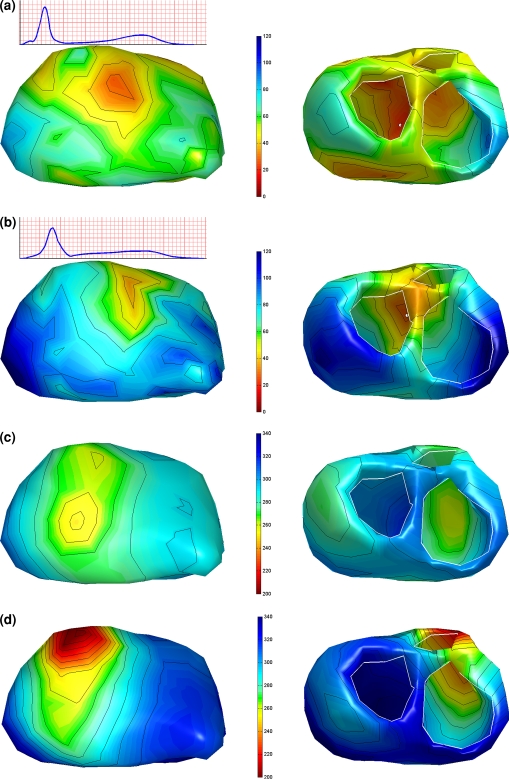

Examples of the inversely computed timing of depolarization and repolarization of the Brugada patient are shown in Fig. 9. These related to two time instants during the procedure: at baseline and just after the last infusion of Ajmaline. The effect of the Ajmaline on the ECG can be observed in the rms signal of the recorded BSPs (insets Fig. 9): the QRS broadened and the ST segment became slightly elevated following the administration of Ajmaline.

Figure 9.

Activation (a, b) and recovery (c, d) of two beats in a Brugada patient during an Ajmaline provocation test. Panels (a) and (c) show the activation respectively the recovery sequence estimated from the baseline ECG. Panels (b) and (d) show the activation respectively the recovery sequence just after the last infusion of the Ajmaline. Color scale is the same for Panels a & b and Panels c & d. Remaining legend as in Fig. 2

The first focal area was found on the left side of the septum for the baseline beat and at peak Ajmaline. For the baseline beat two additional foci were found, one on the left and one on right lateral wall (see Fig. 9a). The estimated activation patterns of both analyzed beats are similar, although the activation times of the Ajmaline beat were later near the left and right base of the heart (Figs. 9a and 9b).

The estimated repolarization times of the baseline beat show a dominant epi- to endocardial recovery sequence. After the last bolus of Ajmaline, the transmural repolarization difference in the left ventricle remained almost unchanged, though slowly shifted with time. Large differences, however, are found in the right ventricle (Fig. 9d). The accompanying ARIs initially show a dispersion of 116 ms increasing up to 193 ms. This expanded range is mainly caused by the very early recovery in the outflow tract area (see Fig. 9d). The corresponding ECGs of both beats are shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10.

The simulated (black lines) and measured (blue lines) ECGs for the baseline beat of the Brugada patient, and the simulated (black lines) and measured (red lines) ECGs of the beat at peak Ajmaline

Overall Performance of the Procedure

For each step in the inverse procedure the correlation and rd values are calculated between the measured ECG and the simulated ECG (see Table 2). For all subjects the resulting inverse procedure rd values were small. The initial estimates, however, showed high rd (>0.7) values despite the fact that the corresponding correlation was well above 80%.

The linear slope of α(δ) in the initial solution was close to −1.32 for most subjects. After optimization the slope values decreased for all cases, except in the Brugada patient at peak Ajmaline (Table 3).

The computation time used by the inverse procedure ranged between ½ a minute (BG) up to 23 min (NH), depending on the number of nodes (Table 1) used in the mesh in the heart’s geometry (Table 4).

Table 4.

Computation times of the focal search algorithm and the optimization procedure

| Subject | Focal search | Optimization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Scans | Computation time (s) | # Iterations | Computation time (s) | |

| NH | 9 | 233 | 10 | 1143 |

| WPW | ||||

| Fusion | 4 | 61 | 17 | 208 |

| AV blocked | 2 | 23 | 85 | 993 |

| BG | ||||

| Baseline | 6 | 6 | 23 | 31 |

| Peak infusion | 1 | 1 | 36 | 46 |

Some foci in the multi-focal search were considered more than once, resulting in more scans than foci. Within the optimization procedure one iteration includes the optimization of depolarization times (δ) and repolarization times (ρ)

Discussion

For all of the three cases presented, the inversely estimated timing of activation and recovery agreed well with available physiological knowledge. The resulting ECGs closely matched the measured ECGs (rd ≤ 0.19, correlation ≥ 0.98, see Table 2). The quality of the results and the required computation time hold promise for the application of this inverse procedure in a clinical setting.

In previous studies the required initial estimates were derived exclusively from the observed BSPs.8,26,38,45 The robustness of these initial estimates was limited in the sense that small variations in the parameters of the first estimate lead to quite different outcomes of the inverse procedure. In the study presented here, the initial estimates are based on knowledge about the electrophysiology of the heart. The results show that this improves the quality of the inverse procedure significantly. The major elements of the inverse procedure are discussed below.

Activation

A first improvement in the initial estimation procedure was the incorporation of global anisotropic propagation in the simulation of ventricular activation. When using an uniform velocity the estimated activation wave revealed earlier epicardial activation for subject NH in the anterior part of the left ventricle.55 Although no data on individual fiber orientation was available, the global handling of trans-mural anisotropy, estimated using common accepted insights,53,54,67 improved the overall performance.

A second improvement concerns the selection of foci in the multi-foci search algorithm. Within this algorithm, the correlation R between measured and simulated ECGs was used, instead of the rd values used previously. The idea to investigate the appropriateness of the correlation arose from the observation that the overall morphology of the simulated wave forms closely corresponded to the measured data, in spite of relatively high rd values. This was first observed in an application to the relatively simple atrial activation sequence, frequently involving just the “focus” in the sinus node region.56 Subsequently, it also proved to be effective in applications to the ventricles.

Each simulated activation sequence of the initial multi-foci search was scaled by an estimation of the global propagation velocity (vℓ) derived from the QRS duration, taking into account the differences in propagation velocity in myocardial and Purkinje tissue. The QRS duration was derived from the rms(t) curve, computed from all leads referred to a zero-mean signal reference.30 This produces the optimal estimate of the global onset and completion of the activation process.

This initial estimation procedure proved to be very insensitive to slight variations in parameters settings. This can be observed from the first subject presented, NH, yielding an initial estimate that agrees well with literature data.10,32,72 The final activation times, resulting from the subsequently applied inverse procedure, globally resemble those of the initial activation sequence (Figs. 3a and 3b). Further visual inspection of the final activation sequence also showed no unphysiological phenomena.

The inverse solutions for the WPW patient have been published by Fisher et al.13 In their report, the solution presented solution was based an initial estimate derived from using the critical point theorem.29 The solution for the fusion beat clearly identified the actual, invasively determined location of the accessory pathway location, but the accompanying initiation of activation at the septum and the right ventricle were not found. In our current inverse procedure, the initial estimated activation sequence of the same beat (see Fig. 7a) the accessory pathway location was identified in the first run of the multi-focal search, followed by locations from where the ventricle normally is activated.10 The estimated activation sequence thus not only shows the correct position of the Kent bundle, but also a true fusion type of activation resulting from early activation in the right ventricle and left septum, as is to be expected in this situation. For the situation in which the AV node was blocked a single focus was found at the approximate location of the Kent bundle (see Fig. 7b).

A reduction in propagation velocity of 20–40% can be found44 after the administration of Ajmaline, which is reflected in the estimated activation sequences before and after Ajmaline administration (compare Figs. 9a and 9b). Note that the earliest site of activation in both sequences are approximately the same. These activation patterns are similar, suggesting that the sodium channel blocker has a global influence on the propagation velocity within the heart (Figs. 9a and 9b) and a more pronounced effect in the right basal area, in accordance with Linnenbank et al.35

Recovery

In previous studies only the cardiac activation times were estimated from body surface potentials.8,35 In the current study the recovery sequence, as quantified by the timing of the steepest down slope of the local transmembrane at the heart’s surface, is included as well. For the initial estimate of the ventricular recovery sequence, ρ, a quantification of the effect of electrotonic interaction on the recovery process is used, expressed by its effect on the local the activation recovery interval (ARI). Few invasive data are available on the ventricular activation recovery intervals.60 Generally these are derived from potentials measured on the endocardial and epicardial aspects of the myocardium.19,32,42

The linear regression slope of the α(δ) curves for all 5 cases was within the range as found by Franz et al.15 (−1.3 ± 0.45). The estimated slopes revealed slightly smaller values in the right ventricle than those in the left ventricle and septum (Fig. 4). These results suggest that electrotonic interaction is a major determinant of the action potential duration. Consequently the ARI depends on the activation time, resulting in similar patterns for ARI and activation times. These findings are in contrast with the ARI values based on the PPS source model found by Ramathan et al.,42 in which local ARI is almost completely uncoupled from the local activation time. The differences in the ARI values estimated by both methods can be attributed to the fact that the local TMP waveforms cannot be extracted uniquely from the, more global, electrograms used in the PPS based inverse procedure to extract local recovery times.

The dispersion in the recovery times found was smaller than those of the activation times, in agreement with the negative slopes observed for the α(δ) function. The ranges of the activation times found were about twice as large as those of the repolarization times for the normal cases (NH and BG (1 min), Table 3). The apex-to-base differences in the recovery times were small (20–30 ms), which is in accordance to literature data.42 At several sites the local transmural recovery differences were more substantial (Figs. 6–9). Such large transmural recovery differences (frequently referred to by the misnomer recovery gradients), were found throughout the ventricles in all ‘normal’ subjects (BG baseline and NH), but not in the right ventricle of the Brugada patient (BG) after the administration of Ajmaline. It is unknown whether the recovery times of the Brugada patient match reality, but the locations having the largest deviations in recovery time do match common knowledge.71 An explanation for the short ARI value (and the advanced activation) might lie in the fact that this area is not activated at all due to structural changes,68 an option not permitted by the presented inverse procedure.

Action Potential Wave Forms of the Source Model

The description of the transmembrane potential waveform used for driving the EDL source model (5), Fig. 1, proved to be adequate. When testing more refined variants only minor differences in the resulting isochrone patterns were observed, which is an indication of the robustness of the inverse procedure (see Appendix).

Limitations

The EDL source model involved assumes a uniform equal anisotropy ratio throughout the myocardium.18 A quantitative judgment on the quality of the initial estimate and its influence on the estimate of activation and recovery times could not be given for want of a complete set of invasive data pertaining to the entire myocardium.

Conclusions

In all three cases, the inversely estimated timing agreed with available physiological knowledge. The progress made in the inverse procedure using an equivalent double layer source model is attributed to our use of initial estimates based on the general electrophysiology of propagation. The quality of the results and the required computation time hold promise for a future application of this inverse procedure in a clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

We would thank Gerald Fisher for providing us with the data of WPW patient. We would also like to thank Pascal van Dessel and his co-workers for permitting us to use the Brugada patient’s data, recorded during an Ajmaline provocation test.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix

In the source model used, the early repolarization phase (1) and plateau phase (2) were not incorporated.33 It was tested whether the incorporation of these phases in the source model influence the estimated activation and recovery times. Initial repolarization was implemented by multiplying the product of (2) and (3) by a “spike function”, defined as

|

13 |

with βp the slope, and τp the timing of the spike. The constant c sets the magnitude of the spike describing phase (1). A down-sloping plateau was accounted for by scaling β1. The resulting waveform of the local source strength, previously described in (5), was

|

14 |

The values of the constants, c = 0.08, τp = δ + 8, and βp = 0.35, were found by tuning the resulting wave form to available literature data.2,6,25,41 Examples of two waveforms, with and without Phase 1 (early repolarization) and 2 (plateau), are shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11.

Examples of TMP wave forms based on (14), red lines (c = 0.08, τp = 8, and βp = 0.35), and (5) blue lines with no spike/plateau. The constants δ and ρ specify two different timings of activation and recovery; the corresponding activation recovery intervals are α = ρ − δ. The numbers (0–4) indicate the phase of the action potential

The activation and recovery times were estimated again, now using the TMP shape including spike and plateau phases. The results were compared to the resulting ECGs, activation and recovery times from the inverse procedure using only the depolarization and repolarization phases (see (5)).

The rms differences in estimated activation and recovery times were small (Table 5), except for the AV-blocked beat of the WPW patient and the Brugada patient at peak Ajmaline delivery. For the Brugada patient, however, early repolarization is found in the outflow tract area in both situations (see Fig. 9d). The WPW patient shows a similar pattern in repolarization for both models, with an average difference in repolarization time of 25 ms. The goodness of fit was comparable for the STT segment of the BSPs for both TMP shape descriptions, as apparent from the average rms values of the differences between measured and simulated ECG signals (Table 6).

Table 5.

Root mean square (rms) differences in the activation times (δ) and repolarization times (ρ) estimated by using two different TMP shape descriptions

| Subject | Timing differences for two source models | |

|---|---|---|

| Depolarization (ms) | Repolarization (ms) | |

| NH | 1.6 | 6.4 |

| WPW | ||

| Fusion | 2.1 | 3.6 |

| AV blocked | 6.8 | 32.5 |

| BG | ||

| Baseline | 3.8 | 9.7 |

| Peak infusion | 3.8 | 23.1 |

Table 6.

Average root mean square (rms) differences in the amplitude of measured and simulated body surface potentials simulated with two different source descriptions

References

- 1.Berger, T., G. Fischer, B. Pfeifer, R. Modre, F. Hanser, T. Trieb, F. X. Roithinger, M. Stuehlinger, O. Pachinger, B. Tilg, et al. Single-beat noninvasive imaging of cardiac electrophysiology of ventricular pre-excitation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48:2045–2052, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bernus, O., R. Wilders, C. W. Zemlin, H. Verschelde, and A. V. Panfilov. A computationally efficient electrophysiological model of human ventricular cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282(6):H2296–H2308, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Burger, H. C., and J. B. V. Milaan. Heart vector and leads. Br. Heart J. 8:157–161, 1946. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Colli-Franzone, P., L. Guerri, S. Tentonia, C. Viganotti, S. Baruffi, S. Spaggiari, and B. Taccardi. A mathematical procedure for solving the inverse potential problem of electrocardiography. Analysis of the time-space accuracy from in vitro experimental data. Math. Biosci. 77:353–396, 1985. [DOI]

- 5.Colli-Franzone, P. C., L. Guerri, B. Taccardi, and C. Viganotti. The Direct and Inverse Potential Problems in Electrocardiology. Numerical Aspects of Some Regularization Methods and Application to Data Collected in Dog Heart Experiments. Pavia: I.A.N.-C.N.R., 1979.

- 6.Conrath, C. E., R. Wilders, R. Coronel, J. M. T. de Bakker, P. Taggart, J. R. de Groot, and T. Opthof. Intercellular coupling through gap junctions masks M cells in the human heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 62(2):407–414, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Cowan, J. C., C. J. Hilton, C. J. Griffiths, S. Tansuphaswadikul, J. P. Bourke, A. Murray, and R. W. F. Campbell. Sequence of epicardial repolarization and configuration of the T wave. Br. Heart J. 60:424–433, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Cuppen, J. J. M. Calculating the isochrones of ventricular depolarization. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comp. 5:105–120, 1984. [DOI]

- 9.Demoulin, J. C., and H. E. Kulbertus. Histopathological examination of concept of left hemiblock. Br. Heart J. 34(8):807–814, 1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Durrer, D., R. T. van Dam, G. E. Freud, M. J. Janse, F. L. Meijler, and R. C. Arzbaecher. Total excitation of the isolated human heart. Circulation 41:899–912, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Durrer, D., and L. H. van der Tweel. Spread of activation in the left ventricular wall of the dog. Am. Heart J. 46:683–691, 1953. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Einthoven, W., and K. de Lint. Ueber das normale menschliche Elektrokardiogram und Uber die capillar-elektrometrische Untersuchung einiger Herzkranken. Pflugers Arch. ges. Physiol. 80:139–160, 1900. [DOI]

- 13.Fischer, G., F. Hanser, B. Pfeifer, M. Seger, C. Hintermuller, R. Modre, B. Tilg, T. Trieb, T. Berger, F. X. Roithinger, et al. A signal processing pipeline for noninvasive imaging of ventricular preexcitation. Methods Inf. Med. 44:588–515, 2005. [PubMed]

- 14.Frank, E. An accurate, clinically practical system for spatial vectorcardiography. Circulation 13(5):737–749, 1956. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Franz, M. R., K. Bargheer, W. Rafflenbeul, A. Haverich, and P. R. Lichtlen. Monophasic action potential mapping in a human subject with normal electrograms: direct evidence for the genesis of the T wave. Circulation 75(2):379–386, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Geselowitz, D. B. Multipole representation for an equivalent cardiac generator. Proc. IRE 48:75–79, 1960.

- 17.Geselowitz, D. B. On the theory of the electrocardiogram. Proc. IEEE 77/6:857–876, 1989. [DOI]

- 18.Geselowitz, D. B. Description of cardiac sources in anisotropic cardiac muscle. Application of bidomain model. J. Electrocardiol. 25(Sup):65–67, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ghanem, R. N., J. E. Burnes, A. L. Waldo, and Y. Rudy. Imaging dispersion of myocardial repolarization. II. Noninvasive reconstruction of epicardial measures. Circulation 104(11):1306–1312, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ghosh, S., and Y. Rudy. Application of L1-norm regularization to epicardial potential solution of the inverse electrocardiography problem. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 37(5):902–912, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Gulrajani, R. M. The forward problem in electrocardiography. Bioelectricity and Biomagnetism. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 348–380, 1998.

- 22.Gulrajani, R. M. The inverse problem in electrocardiography. Bioelectricity and Biomagnetism. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 381–431, 1998.

- 23.Gulrajani, R. M., P. Savard, and F. A. Roberge. The inverse problem in electrocardiography: solution in terms of equivalent sources. CRC Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16:171–214, 1988. [PubMed]

- 24.Haws, C. W., and R. L. Lux. Correlation between in vivo transmembrane action potential durations and activation-recovery intervals from electrograms. Circulation 81(1):281–288, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Hopenfeld, B. A mathematical analysis of the action potential plateau duration of a human ventricular myocyte. J. Theor. Biol. 240(2):311–322, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Huiskamp, G. J. H., and A. van Oosterom. The depolarization sequence of the human heart surface computed from measured body surface potentials. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 35(12):1047–1058, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Huiskamp, G. J. M. Difference formulas for the surface Laplacian on a triangulated surface. J. Comput. Phys. 95(2):477–496, 1991. [DOI]

- 28.Huiskamp, G. J. M. Simulation of depolarization and repolarization in a membrane equations based model of the anisotropic ventricle. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 45(7):847–855, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Huiskamp, G. J. M., and F. Greensite. A new method for myocardial activation imaging. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 44(6):433–446, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Ihara, Z., A. van Oosterom, and R. Hoekema. Atrial repolarization as observable during the PQ interval. J. Electrocardiol. 39(3):290–297, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Jacquemet, V., A. van Oosterom, J. M. Vesin, and L. Kappenberger. Analysis of electrocardiograms during atrial fibrillation. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 25(6):79–88, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Janse, M. J., E. A. Sosunov, R. Coronel, T. Opthof, E. P. Anyukhovsky, J. M. T. de Bakker, A. N. Plotnikov, I. N. Shlapakova, P. Danilo, Jr., J. G. P. Tijssen, et al. Repolarization gradients in the canine left ventricle before and after induction of short-term cardiac memory. Circulation 112(12):1711–1718, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Katz, A. M. Physiology of the Heart. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

- 34.Kléber, A. G., and Y. Rudy. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Phys. Rev. 84(2):431–488, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Linnenbank, A. C., A. van Oosterom, T. F. Oostendorp, P. van Dessel, A. C. Van Rossum, R. Coronel, H. L. Tan, and J. M. De Bakker. Non-invasive imaging of activation times during drug-induced conduction changes. World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering, IFMBE, Seoul, 2006.

- 36.Marquardt, D. W. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of non-linear parameters. J. Soc. Indust. Appl. Math. 11(2):431–441, 1963. [DOI]

- 37.Martin, R. O., and T. C. Pilkington. Unconstrained inverse electrocardiography. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 19(4):276–285, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Modre, R., B. Tilg, G. Fischer, F. Hanser, B. Messarz, and J. Segers. Atrial noninvasive activation mapping of paced rhythm data. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 13:712–719, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Modre, R., B. Tilg, G. Fisher, and P. Wach. Noninvasive myocardial activation time imaging: a novel; inverse algorithm applied to clinical ECG mapping data. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 49(10):1153–1161, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Oosthoek, P. W., S. Viragh, W. H. Lamers, and A. F. Moorman. Immunohistochemical delineation of the conduction system. II. The atrioventricular node and Purkinje fibers. Circ. Res. 73(3):482–491, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Potse, M., B. Dubé, J. Richer, A. Vinet, and R. M. Gulrajani. A comparison of monodomain and bidomain reaction-diffusion models for action potential propagation in the human heart. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 53(12):2425–2435, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Ramanathan, C., P. Jia, R. Ghanem, K. Ryu, and Y. Rudy. Activation and repolarization of the normal human heart under complete physiological conditions. PNAS 103(16):6309–6314, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Roberts, D., L. Hersh, and A. Scher. Influence of cardiac fiber orientation on wavefront voltage, conduction velocity, and tissue resistivity in the dog. Circ. Res. 44:701–712, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Romero Legarreta, I., S. Bauer, R. Weber dos Santos, H. Koch, and M. Bär. Spatial Properties and Effects of Ajmaline for Epicardial Propagation on Isolated Rabbit Hearts: Measurements and a Computer Study. NC, USA: Computers in Cardiology Durham, 2007.

- 45.Roozen, H., and A. van Oosterom. Computing the activation sequence at the ventricular heart surface from body surface potentials. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 25:250–260, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Rudy, Y., and B. J. Messinger-Rapport. The inverse problem in electrocardiology: solutions in terms of epicardial potentials. CRC Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16:215–268, 1988. [PubMed]

- 47.Salu, Y. Relating the multipole moments of the heart to activated parts of the epicardium and endocardium. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 6:492–505, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Sano, T., N. Takayama, and T. Shimamoto. Directional differences of conduction velocity in the cardiac ventricular syncytium studied by microelectrodes. Circ. Res. VII:262–267, 1959. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Schalij, M. J., M. J. Janse, A. van Oosterom, E. E. van der Wall, and H. J. J. Wellens (Eds.). Einthoven 2002: 100 Year of Electrocardiography. Leiden, The Einthoven Foundation, 2002.

- 50.Scher, A. M., A. C. Young, A. L. Malmgren, and R. R. Paton. Spread of electrical activity through the wall of the ventricle. Cardiovasc. Res. 1:539–547, 1953. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Simms, H. D., and D. B. Geselowitz. Computation of heart surface potentials using the surface source model. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 6:522–531, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Spach, M. S., and P. C. Dolber. Relating extracellular potentials and their derivatives to anisotropic propagation at a microscopic level in human cardiac muscle. Evidence for electrical uncoupling of side-to-side fiber connections with increasing age. Circ. Res. 58(3):356–371, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Spach, M. S., W. T. Miller, E. Miller-Jones, R. B. Warren, and R. C. Barr. Extracellular potentials related to intracellular action potentials during impulse conduction in anisotropic canine cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 45:188–204, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Streeter, D. D. J., H. M. Spotnitz, D. P. Patel, J. J. Ross, and E. H. Sonnenblick. Fiber orientation in the canine left ventricle during diastole and systole. Circ. Res. 24:339–347, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.van Dam, P., T. Oostendorp, and A. van Oosterom. Application of the fastest route algorithm in the interactive simulation of the effect of local ischemia on the ECG. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 47(1):11–20, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.van Dam, P. M., and A. van Oosterom. Atrial excitation assuming uniform propagation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 14(s10):S166–S171, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.van Dam, R. T., and M. J. Janse. Activation of the heart. In: Comprehensive Electrocardiology, edited by P. W. Macfarlane and T. T. V. Lawrie. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1989.

- 58.van Oosterom, A. (Ed.). Electrocardiography. In: The Biophysics of Heart and Circulation. Bristol, Inst of Physics Publ., 1993.

- 59.van Oosterom, A. Genesis of the T wave as based on an equivalent surface source model. J. Electrocardiogr. 34(Supplement 2001):217–227, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.van Oosterom, A. The equivalent surface source model in its application to the T wave. In: Electrocardiology’01. Univ Press São Paolo, 2002.

- 61.van Oosterom, A. The singular value decomposition of the T wave: its link with a biophysical model of repolarization. Int. J. Bioelectromagnetism 4:59–60, 2002.

- 62.van Oosterom, A. Solidifying the solid angle. J. Electrocardiol. 35S:181–192, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.van Oosterom, A. The dominant T wave and its significance. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 14(10 Suppl):S180–S187, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.van Oosterom, A. The dominant T wave. J. Electrocardiol. 37(Suppl):193–197, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.van Oosterom, A., and V. Jacquemet. The effect of tissue geometry on the activation recovery interval of atrial myocytes. Physica D 238(11–12), 2009.

- 66.van Oosterom, A., and P. M. van Dam. The intra-myocardial distance function as used in the inverse computation of the timing of depolarization and repolarization. In: Computers in Cardiology. Lyon, France: IEEE Computer Society Press, 2005.

- 67.Wang, Y., and Y. Rudy. Action potential propagation in inhomogeneous cardiac tissue: safety factor considerations and ionic mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278:H1019–H1029, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Wilde, A. A. M., and C. Antzelevitch. The continuing story: the aetiology of Brugada syndrome: functional or structural basis? Eur. Heart J. 24(22):2073, 2003. 14613750 [DOI]

- 69.Wilson, F. N., A. G. Macleod, and P. S. Barker. The distribution of action currents produced by the heart muscle and other excitable tissues immersed in conducting media. J. Gen. Physiol. 16:423–456, 1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Wilson, R. J. Introduction to Graph Theory. London: Longman, 1975

- 71.Wolpert, C., C. Echternach, C. Veltmann, C. Antzelevitch, G. P. Thomas, S. Spehl, F. Streitner, J. Kuschyk, R. Schimpf, K. K. Haase, et al. Intravenous drug challenge using flecainide and ajmaline in patients with Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2(3):254–260, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Wyndham, C. R. M., T. Smith, A. Saxema, S. Engleman, R. M. Levitsky, and K. M. Rosen. Epicardial activation of the intact human heart without conduction defect. Circulation 59(1):161–168, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed]