Abstract

Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) is a common disorder wherein symptoms of IBS begin after an episode of acute gastroenteritis. Published studies have reported incidence of PI-IBS to range between 5% and 32%. The mechanisms underlying the development of PI-IBS are not fully understood, but are believed to include persistent sub-clinical inflammation, changes in intestinal permeability and alteration of gut flora. Individual studies have suggested that risk factors for PI-IBS include patients’ demographics, psychological disorders and the severity of enteric illness. However, PI-IBS remains a diagnosis of exclusion with no specific disease markers and, to date, no definitive therapy exists. The prognosis of PI-IBS appears favorable with spontaneous and gradual resolution of symptoms in most patients.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Functional colonic disease, Gastroenteritis, Functional bowel disorder

INTRODUCTION

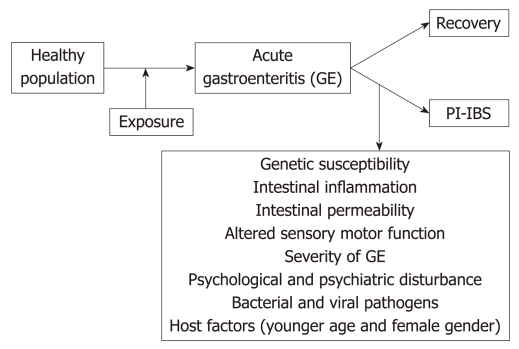

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal discomfort and altered bowel habit with no abnormality on routine diagnostic tests[1,2]. In some patients, IBS symptoms arise de novo following an exposure to acute gastroenteritis (GE). This phenomenon, known as post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), denotes the persistence of abdominal discomfort, bloating and diarrhea that continue despite clearance of the inciting pathogen[3–15]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that the risk of developing IBS increases six-fold after gastrointestinal infection[16] and remains elevated for at least 2-3 years post-infection. The current conceptual framework regarding the pathophysiologic mechanism for PI-BS suggests that PI-IBS is associated with altered motility, increased intestinal permeability, increased numbers of enterochromaffin cells and persistent intestinal inflammation, characterized by increased numbers of T-lymphocytes and mast cells, and increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines[3,12,17,18] (Figure 1). This therefore suggests that an exposure to pathogenic organisms disrupts intestinal barrier function, alters neuromuscular function and triggers chronic inflammation which sustain IBS symptoms. We provide herein a review of PI-IBS epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

A link between IBS and enteric infection was first proposed by Stewart more than five decades ago[19]. A subsequent retrospective study by Chaudhary and Truelove found that a substantial proportion of patients with IBS reported the onset of their symptoms after an acute episode of GE[20]. Since then, various prospective and retrospective studies from the United Kingdom, North America, Spain, Korea, Israel and New Zealand have reported the incidence or prevalence of PI-IBS to range from 5% to 32%[4–13,21–25]. Consistent among these studies is the suggestion that PI-IBS is a global phenomenon, and not unique to any ethnic group or environment. Reported estimates of the prevalence/incidence of PI-IBS vary in part because of differences in study methodology, including the criteria used to define IBS (Table 1). In general, Rome II criteria generate lower estimates than Rome I or III.

Table 1.

Estimates of incidence of PI-IBS1

| Author | Study type | Control group | Type of exposure | Follow-up (mo) | Criteria for diagnosis of IBS | Mean quality assessment score | Incidence of IBS in exposed cohort | Country |

| McKendrick[24] | Prospective | None | Confirmed Salmonella | 12 | Rome I | 14.5 | 12/38 = 31.6% | United Kingdom |

| Neal[13] | Prospective | None | Confirmed-bacterial GE | 6 | Modified Rome I | 16.0 | 23/366 = 6.3% | United Kingdom |

| Gwee[22] | Prospective | None | Confirmed gastroenteritis | 6 | Clinical assessment | 21.0 | 9/86 = 10.5% | United Kingdom |

| Gwee[28] | Prospective | None | Confirmed Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella | 12 | Rome I | 21.5 | 22/109 = 20.2% | United Kingdom |

| Rodríguez[6] | Prospective | Matched from database | Confirmed bacterial GE | 12 | Physician diagnosis | 19.0 | 14/318 = 4.4% | United Kingdom |

| Ilnyckyj[5] | Prospective | Uninfected contemporaneous | Self reported (traveler’s diarrhea) | 3 | Rome I | 22.5 | 2/48 = 4.2% | Canada |

| Dunlop[3] | Prospective | None | Self reported (presumed Campylobacter) | 3 | Rome I | 21.0 | 103/747 = 13.8% | United Kingdom |

| Parry[27] | Prospective Case control | Matched from database | Confirmed Campylobacter, Salmonella | 3-6 | Rome II | 23.5 | 18/128 = 14.1% | United Kingdom |

| Wang[12] | Prospective | Uninfected family | Confirmed Shigella | 12, 24 | Rome II | 23.5 | 24/295 = 8.1% | China |

| Okhuysen[15] | Prospective | None | Self-reported travelers’ diarrhea | 6 | Rome II | 20.0 | 6/169 = 3.6% | United States |

| Kim[4], Ji[23], Jung[41] | Prospective | Uninfected contemporaneous | Self reported (presumed Shigella) | 12, 36, 60 | Modified Rome I & II | 24.5 | 15/143 = 10.5% | South Korea |

| Mearin[25] | Prospective | Uninfected contemporaneous | Self reported (presumed Salmonella) | 3, 6, 12 | Rome II | 22.5 | 27/467 = 5.8% | Spain |

| Marshall[11] | Prospective | Uninfected contemporaneous | Self reported (presumed E. coli, Campylobacter) | 24-36 | Rome I | 26.5 | 417/1368 = 30.5% | Canada |

| Borgaonkar[21] | Prospective | None | Confirmed (any bacterial pathogen) | 3 | Manning & Rome I | 20.0 | 7/191 = 3.7% | Canada |

| Moss-Morris[26] | Prospective | Mononucleosis | Confirmed Campylobacter | 3, 6 | Rome I & II | 21.5 | 59/592 = 10.0% | New Zealand |

| Stermer[14] | Prospective | Uninfected contemporaneous | Self reported (travelers’ diarrhea) | 6 | Rome II | 13.6 | 13/118 = 11.0% | Israel |

| Marshall[10] | Prospective | Uninfected contemporaneous | Self reported (presumed viral) | 3, 6, 12, 24 | Rome I | 23.5 | 15/92 = 16.3% | Canada |

| Spence[30] | Prospective | None | Confirmed Campylobacter | 3, 6 | Rome I & II | 24.0 | 63/620 = 10.2% | New Zealand |

Thabane et al. APT 2007; 26: 535-544.

Unlike sporadic IBS, PI-IBS has a defined moment of onset. Features of the inciting infectious illness such as diarrhea, abdominal cramps, increased stool frequency, bloody or mucous stools, positive stool culture and weight loss are potent predictors of long term outcome. The risk of PI-IBS appears to correlate with the severity of the acute enteric infection, increasing at least two-fold if diarrhea lasts more than 1 wk and over threefold if diarrhea lasts more than 3 wk[11,13]. Abdominal cramps, weight loss and bloody stools are also associated with increased risk, with abdominal cramps increasing the risk fourfold[11,12]. Various bacterial pathogens including Campylobacter, Shigella, Salmonella and Escherichia coli (E. coli) 0157:H7[11,12,22–24,26,27] have been implicated in the development of PI-IBS but it remains unclear whether all organisms confer an equivalent risk. Viral GE appears to cause a more transient form of PI-IBS than bacterial pathogen dysentery[10].

Other reported risk factors for PI-IBS include host factors, and psychological disorders[11–13,22,24,28]. Despite the fact that there are no reported gender differences in the severity of initial infectious illness or immune response, the reported risk of developing PI-IBS is higher among females than males with an adjusted relative risk ranging from 1.47 to 2.86[11,13,29,30]. The female predisposition for PI-IBS may be confounded by a female preponderance of psychological distress. In a study by Gwee et al[22], female gender was no longer a significant risk factor when psychological variables were controlled in a multivariate analysis. In two studies, the risk of developing PI-IBS decreased with increasing age[11] and age above 6 years was reported to have a protective effect with adjusted relative risk of 0.36[13]. Dunlop et al[31] demonstrated that older individuals have fewer lymphocytes and mast cells in the rectal mucosa, which may attenuate the inflammatory response to luminal antigens and yield a reduced risk of IBS.

Just as psychological disorders have been associated with development of sporadic IBS, Sykes et al[32] observed that people with premorbid psychiatric diagnoses, particularly anxiety disorders, are also at increased risk of PI-IBS after acute GE. In addition, depression, neuroticism, somatisation, stress and negative perception of illness have all been linked to PI-IBS[22,27,30,33]. In a recent study, patients who developed PI-IBS had significantly higher levels of perceived stress (OR 1.10, 95% CI: 1.02-1.15), anxiety (OR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.05-1.23), somatisation (OR 1.17, 95% CI: 1.02-1.35) and negative illness beliefs (OR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.03-1.27) at the time of infection than those who did not develop PI-IBS[30]. Furthermore, Gwee et al[22] showed that patients who developed IBS reported more life events and had higher hypochondriasis scores. These observations suggest a psychological-environmental interaction wherein exposure to GE may trigger symptoms that are sustained by psychological disturbances[30]. This paradigm provides support for cognitive-behavioral therapy as a treatment for PI-IBS.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PI-IBS patients are more likely than sporadic IBS patients to exhibit a diarrhea-predominant phenotype[11,17,34]. Spiller found that serial intestinal biopsies from patients recovering from Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni)showed persistent inflammation with elevated T lymphocytes and calprotectin-positive macrophages, possibly as a response to mucosal injury and inflammation[18]. Dunlop et al[3] noted a 25% increase in rectal enterochromaffin cells in patients with PI-IBS, compared to those with sporadic IBS or healthy controls. Significant increases in postprandial plasma serotonin levels have also been seen in PI-IBS and in sporadic constipation-predominant IBS[35]. Gwee et al[36] reported increased expression of IL-1β in rectal biopsies from patients with PI-IBS, when compared with those who suffered infectious enteritis but did not develop PI-IBS. Wang et al[37] also observed increased IL-1β in patients with PI-IBS after Shigella infection when compared with patients with sporadic IBS[12].

Patients with PI-IBS also demonstrate increased small intestinal permeability compared to non-IBS controls, suggesting a defect in epithelial integrity that might promote intestinal inflammation[18]. In one study, an increased lactulose-mannitol fractional excretion ratio was observed among patients with IBS 2 years after a waterborne outbreak of GE involving C. jejuni and E. coli 0157:H7. In this cohort, increased permeability was associated with increased stool frequency[37]. Similar elevations in gut permeability were also observed by Spiller et al[18]. Increased intestinal permeability can promote inflammation by facilitating exposure of the submucosa to luminal antigens with subsequent disturbance of enteric sensation and motility.

There is evidence that genetic risk factors may contribute to PI-IBS pathophysiology. A recent study by Villani et al[38] identified three candidate gene variants, namely TLR9, CDH1 and IL6, which were associated with development of IBS following acute GE. These observations suggest that PI-IBS might result from abnormalities in genes encoding epithelial barrier functions and innate immune responses to enteric bacteria. This discovery is consistent with a paradigm of PI-IBS pathogenesis involving decreased mucosal barrier function, low grade inflammation, and immune activation in the colonic mucosa. Future studies are needed to confirm these potential candidate gene variant associations.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis of PI-IBS appears favorable with spontaneous and gradual resolution of symptoms in most patients. In the largest and longest prospective cohort study of PI-IBS, the prevalence of PI-IBS in a Canadian cohort dropped from 31% at 2 years to 23% after 4 years and 17% after 6 years[39,40]. After 6 years, the incidence of new IBS was no longer increased among those exposed to the initial infection when compared to unexposed controls. A similar decline was reported in an Asian and in a British study, where half of patients recovered 5 and 6 years respectively, after an exposure to acute GE[41,42]. In the same Asian follow up study, a 25% recovery rate was reported 3 years after infection[4]. In studies that have followed patients for only 1 year after outbreaks of bacterial dysentery, the prevalence of IBS has remained relatively stable[23,43]. Of note, in the only study to date which has followed an outbreak of viral GE, the prevalence of IBS symptoms remained elevated for only 3 mo after infection[10]. This suggests that viral GE may be associated with a more transient functional disturbance.

THERAPY

To date there exist no therapies proven to be effective specifically for the management of PI-IBS. Because the phenomenon of PI-IBS is clinically indistinguishable from sporadic IBS, conventional approaches to the management of functional bowel disorders should be adopted. Given a limited insight into the pathogenesis of sporadic IBS, these approaches consist largely of non-specific measures intended to relieve symptoms. However, our enhanced understanding of the pathogenesis of PI-IBS provides a compelling rationale for some specific approaches that target key mechanisms. These warrant further study in clinical trials.

Acute GE can shift colonic flora, which may in turn induce or promote many of the changes in physiology noted above. Modulation of the flora with probiotics, antibiotics or prebiotics can down-regulate inflammation, improve barrier function and reduce visceral sensitivity[44–50]. Probiotics have been proven effective in preventing or attenuating acute GE[51–53]. However, no study has yet assessed the efficacy of interventions that modulate gut flora for preventing or treating PI-IBS.

The observed increases in enterochromaffin cell numbers and post-prandial serotonin release in PI-IBS[18,33] suggest that serotonergic therapies might prove particularly effective in this population. While the therapeutic gain associated with 5-HT3 antagonists[54–62] and 5-HT4 agonists[63–72] in treatment of sporadic IBS has been small, patients with PI-IBS are relatively more homogeneous and might demonstrate enhanced efficacy. No study of such interventions in the management of PI-IBS has been reported.

There remains little doubt that PI-IBS is associated with persistent intestinal inflammation, and that inflammation itself can disturb gut function and generate symptoms. An underpowered randomized trial of prednisolone for treatment of established PI-IBS failed to show a significant improvement in symptoms, but did show a reduction in intestinal enterochromaffin cell and lymphocyte counts[73]. In animal models, early corticosteroid therapy has been shown to attenuate post-infectious neuromuscular dysfunction[74,75]. Hence it remains plausible that corticosteroids given to patients with GE at high risk of PI-IBS would be effective in preventing or attenuating chronic symptoms. Locally active steroids with reduced systemic toxicity, such as budesonide, are particularly attractive for this indication.

CONCLUSION

PI-IBS is a common complication of acute enteric infection. While the epidemiology and natural history of this clinical phenomenon have been well characterized, our understanding of its pathophysiology remains limited. Future research is needed to further define this complex host-microbe interaction and provide new tools for prevention and management.

Peer reviewer: Ami D Sperber, MD, MSPH, Professor of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Soroka Medical Center, Beer-Sheva 84101, Israel

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasler WL, Owyang C. Irritable bowel syndrome. In: T Yamada., editor. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 2nd ed. Lippincott: Philadelphia; 1995. pp. 1832–1855. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Spiller RC. Distinctive clinical, psychological, and histological features of postinfective irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1578–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HS, Kim MS, Ji SW, Park H. [The development of irritable bowel syndrome after Shigella infection: 3 year follow-up study] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47:300–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilnyckyj A, Balachandra B, Elliott L, Choudhri S, Duerksen DR. Post-traveler's diarrhea irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:596–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodríguez LA, Ruigómez A. Increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome after bacterial gastroenteritis: cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318:565–566. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Panés J. Risk of irritable bowel syndrome after an episode of bacterial gastroenteritis in general practice: influence of comorbidities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:465–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soyturk M, Akpinar H, Gurler O, Pozio E, Sari I, Akar S, Akarsu M, Birlik M, Onen F, Akkoc N. Irritable bowel syndrome in persons who acquired trichinellosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1064–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piche T, Vanbiervliet G, Pipau FG, Dainese R, Hébuterne X, Rampal P, Collins SM. Low risk of irritable bowel syndrome after Clostridium difficile infection. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:727–731. doi: 10.1155/2007/262478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall JK, Thabane M, Borgaonkar MR, James C. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome after a food-borne outbreak of acute gastroenteritis attributed to a viral pathogen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:457–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, Clark WF, Salvadori M, Collins SM. Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:445–450; quiz 660. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang LH, Fang XC, Pan GZ. Bacillary dysentery as a causative factor of irritable bowel syndrome and its pathogenesis. Gut. 2004;53:1096–1101. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.021154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neal KR, Hebden J, Spiller R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ. 1997;314:779–782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stermer E, Lubezky A, Potasman I, Paster E, Lavy A. Is traveler's diarrhea a significant risk factor for the development of irritable bowel syndrome? A prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:898–901. doi: 10.1086/507540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, Carlin L, Forbes C, DuPont HL. Post-diarrhea chronic intestinal symptoms and irritable bowel syndrome in North American travelers to Mexico. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1774–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thabane M, Kottachchi DT, Marshall JK. Systematic review and meta-analysis: The incidence and prognosis of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:535–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheatcroft J, Wakelin D, Smith A, Mahoney CR, Mawe G, Spiller R. Enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia and decreased serotonin transporter in a mouse model of postinfectious bowel dysfunction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:863–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiller RC, Jenkins D, Thornley JP, Hebden JM, Wright T, Skinner M, Neal KR. Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47:804–811. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.6.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart GT. Post-dysenteric colitis. Br Med J. 1950;1:405–409. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4650.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhary NA, Truelove SC. The irritable colon syndrome. A study of the clinical features, predisposing causes, and prognosis in 130 cases. Q J Med. 1962;31:307–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borgaonkar MR, Ford DC, Marshall JK, Churchill E, Collins SM. The incidence of irritable bowel syndrome among community subjects with previous acute enteric infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1026–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9348-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, McKendrick MW, Collins SM, Walters SJ, Underwood JE, Read NW. The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut. 1999;44:400–406. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji S, Park H, Lee D, Song YK, Choi JP, Lee SI. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome in patients with Shigella infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:381–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKendrick MW, Read NW. Irritable bowel syndrome--post salmonella infection. J Infect. 1994;29:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(94)94871-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mearin F, Badía X, Balboa A, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, Díaz-Rubio M, Fueyo A, Ponce J, Roset M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence varies enormously depending on the employed diagnostic criteria: comparison of Rome II versus previous criteria in a general population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1155–1161. doi: 10.1080/00365520152584770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss-Morris R, Spence M. To "lump" or to "split" the functional somatic syndromes: can infectious and emotional risk factors differentiate between the onset of chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome? Psychosom Med. 2006;68:463–469. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221384.07521.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parry SD, Stansfield R, Jelley D, Gregory W, Phillips E, Barton JR, Welfare MR. Does bacterial gastroenteritis predispose people to functional gastrointestinal disorders? A prospective, community-based, case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1970–1975. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gwee KA, Graham JC, McKendrick MW, Collins SM, Marshall JS, Walters SJ, Read NW. Psychometric scores and persistence of irritable bowel after infectious diarrhoea. Lancet. 1996;347:150–153. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuteja AK, Talley NJ, Gelman SS, Alder SC, Thompson C, Tolman K, Hale DC. Development of functional diarrhea, constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and dyspepsia during and after traveling outside the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spence MJ, Moss-Morris R. The cognitive behavioural model of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective investigation of patients with gastroenteritis. Gut. 2007;56:1066–1071. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Spiller RC. Age-related decline in rectal mucosal lymphocytes and mast cells. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1011–1015. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sykes MA, Blanchard EB, Lackner J, Keefer L, Krasner S. Psychopathology in irritable bowel syndrome: support for a psychophysiological model. J Behav Med. 2003;26:361–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1024209111909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, Spiller RC. Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety, and depression in postinfectious IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1651–1659. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, Sampson JE, Chen J, Blaszyk H, Crowell MD, Sharkey KA, Gershon MD, Mawe GM, et al. Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1657–1664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunlop SP, Coleman NS, Blackshaw E, Perkins AC, Singh G, Marsden CA, Spiller RC. Abnormalities of 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gwee KA, Collins SM, Read NW, Rajnakova A, Deng Y, Graham JC, McKendrick MW, Moochhala SM. Increased rectal mucosal expression of interleukin 1beta in recently acquired post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:523–526. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, Clark W, Meddings J, Collins SM. Intestinal permeability in patients with irritable bowel syndrome after a waterborne outbreak of acute gastroenteritis in Walkerton, Ontario. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1317–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villani A, Lemire M, Thabane M. Genetic risk factors for post-infectious IBS in the E. coli 0157:H7 outbreak in Walkerton (Canada) in 2000. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:A122. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, Clark WF. Prognosis in post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: A four year follow up after the Walkerton waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:A52. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, Clark WF, Collins SM. Prognosis in post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: A six year follow up after the Walkerton waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A66. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jung IS, Kim HS, Park H, Lee SI. The clinical course of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome: a five-year follow-up study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:534–540. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818c87d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neal KR, Barker L, Spiller RC. Prognosis in post-infective irritable bowel syndrome: a six year follow up study. Gut. 2002;51:410–413. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mearin F, Pérez-Oliveras M, Perelló A, Vinyet J, Ibañez A, Coderch J, Perona M. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: one-year follow-up cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:98–104. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verdú EF, Bercík P, Bergonzelli GE, Huang XX, Blennerhasset P, Rochat F, Fiaux M, Mansourian R, Corthésy-Theulaz I, Collins SM. Lactobacillus paracasei normalizes muscle hypercontractility in a murine model of postinfective gut dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:826–837. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verdú EF, Bercik P, Verma-Gandhu M, Huang XX, Blennerhassett P, Jackson W, Mao Y, Wang L, Rochat F, Collins SM. Specific probiotic therapy attenuates antibiotic induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. Gut. 2006;55:182–190. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.066100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Camilleri M. Probiotics and irritable bowel syndrome: rationale, putative mechanisms, and evidence of clinical efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:264–269. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camilleri M. Probiotics and irritable bowel syndrome: rationale, mechanisms, and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42 Suppl 3 Pt 1:S123–S125. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181574393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Medici M, Vinderola CG, Weill R, Perdigón G. Effect of fermented milk containing probiotic bacteria in the prevention of an enteroinvasive Escherichia coli infection in mice. J Dairy Res. 2005;72:243–249. doi: 10.1017/s0022029905000750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Attar A, Flourié B, Rambaud JC, Franchisseur C, Ruszniewski P, Bouhnik Y. Antibiotic efficacy in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-related chronic diarrhea: a crossover, randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:794–797. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Stefano M, Malservisi S, Veneto G, Ferrieri A, Corazza GR. Rifaximin versus chlortetracycline in the short-term treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:551–556. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rohde CL, Bartolini V, Jones N. The use of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea with special interest in Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Nutr Clin Pract. 2009;24:33–40. doi: 10.1177/0884533608329297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shukla G, Devi P, Sehgal R. Effect of Lactobacillus casei as a probiotic on modulation of giardiasis. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2671–2679. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Resta-Lenert S, Barrett KE. Live probiotics protect intestinal epithelial cells from the effects of infection with enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) Gut. 2003;52:988–997. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Camilleri M, Chey WY, Mayer EA, Northcutt AR, Heath A, Dukes GE, McSorley D, Mangel AM. A randomized controlled clinical trial of the serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist alosetron in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1733–1740. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.14.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Camilleri M, Northcutt AR, Kong S, Dukes GE, McSorley D, Mangel AW. Efficacy and safety of alosetron in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Drossman DA, Heath A, Dukes GE, McSorley D, Kong S, Mangel AW, Northcutt AR. Improvement in pain and bowel function in female irritable bowel patients with alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1149–1159. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang L, Ameen VZ, Dukes GE, McSorley DJ, Carter EG, Mayer EA. A dose-ranging, phase II study of the efficacy and safety of alosetron in men with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krause R, Ameen V, Gordon SH, West M, Heath AT, Perschy T, Carter EG. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg and 1 mg alosetron in women with severe diarrhea-predominant IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1709–1719. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lembo AJ, Olden KW, Ameen VZ, Gordon SL, Heath AT, Carter EG. Effect of alosetron on bowel urgency and global symptoms in women with severe, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: analysis of two controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:675–682. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones RH, Holtmann G, Rodrigo L, Ehsanullah RS, Crompton PM, Jacques LA, Mills JG. Alosetron relieves pain and improves bowel function compared with mebeverine in female nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1419–1427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chey WD, Chey WY, Heath AT, Dukes GE, Carter EG, Northcutt A, Ameen VZ. Long-term safety and efficacy of alosetron in women with severe diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2195–2203. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bardhan KD, Bodemar G, Geldof H, Schütz E, Heath A, Mills JG, Jacques LA. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled dose-ranging study to evaluate the efficacy of alosetron in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:23–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Müller-Lissner S, Holtmann G, Rueegg P, Weidinger G, Löffler H. Tegaserod is effective in the initial and retreatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:11–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chey WD, Paré P, Viegas A, Ligozio G, Shetzline MA. Tegaserod for female patients suffering from IBS with mixed bowel habits or constipation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1217–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Stefano M, Miceli E, Mazzocchi S, Tana P, Missanelli A, Corazza GR. Effect of tegaserod on recto-sigmoid tonic and phasic activity in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1720–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fock KM, Wagner A. Safety, tolerability and satisfaction with tegaserod therapy in Asia-Pacific patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1190–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harish K, Hazeena K, Thomas V, Kumar S, Jose T, Narayanan P. Effect of tegaserod on colonic transit time in male patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1183–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tack J, Müller-Lissner S, Bytzer P, Corinaldesi R, Chang L, Viegas A, Schnekenbuehl S, Dunger-Baldauf C, Rueegg P. A randomised controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of repeated tegaserod therapy in women with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gut. 2005;54:1707–1713. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.070789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Müller-Lissner SA, Fumagalli I, Bardhan KD, Pace F, Pecher E, Nault B, Rüegg P. Tegaserod, a 5-HT(4) receptor partial agonist, relieves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1655–1666. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Novick J, Miner P, Krause R, Glebas K, Bliesath H, Ligozio G, Rüegg P, Lefkowitz M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tegaserod in female patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1877–1888. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kellow J, Lee OY, Chang FY, Thongsawat S, Mazlam MZ, Yuen H, Gwee KA, Bak YT, Jones J, Wagner A. An Asia-Pacific, double blind, placebo controlled, randomised study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:671–676. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nyhlin H, Bang C, Elsborg L, Silvennoinen J, Holme I, Rüegg P, Jones J, Wagner A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study to evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:119–126. doi: 10.1080/00365520310006748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, Naesdal J, Borgaonker M, Collins SM, Spiller RC. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of prednisolone in post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Deng Y, Vallance B, Blennerhassett P, Collins SM. Role of immunologic factors and cyclooxygenase 2 in persistent postinfective enteric muscle dysfunction in mice. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1729–1736. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sukhdeo MV, Croll NA. Gut propulsion in mice infected with Trichinella spiralis. J Parasitol. 1981;67:906–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]