Abstract

Recently, several reports have demonstrated that fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is useful in differentiating between benign and malignant lesions in the gallbladder. However, there is a limitation in the ability of FDG-PET to differentiate between inflammatory and malignant lesions. We herein present a case of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis misdiagnosed as gallbladder carcinoma by ultrasonography and computed tomography. FDG-PET also showed increased activity. In this case, FDG-PET findings resulted in a false-positive for the diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma.

Keywords: Fluorodeoxyglucose F18, Positron-emission tomography, Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, Gallbladder cancer

INTRODUCTION

Patients with abnormal thickening of the gallbladder wall caused by benign lesions such as chronic cholecystitis and adenomyomatosis are often encountered in daily clinical practice. Sometimes, it is difficult to differentiate these from gallbladder carcinoma by the conventional imaging techniques of ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Recently, several reports have demonstrated that fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is useful in differentiating between benign and malignant lesions in the gallbladder[1–5]. However, 18F-FDG is not specific for malignant lesions, and can accumulate in inflammatory lesions with increased glucose metabolism. We present a patient with irregular thickening of the gallbladder wall which was diagnosed as a gallbladder carcinoma by ultrasonography and CT. FDG-PET showed increased activity. However, postoperative pathological examination revealed a xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) with no evidence of malignancy. In this case, FDG-PET, ultrasonography and CT resulted in a misdiagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma.

CASE REPORT

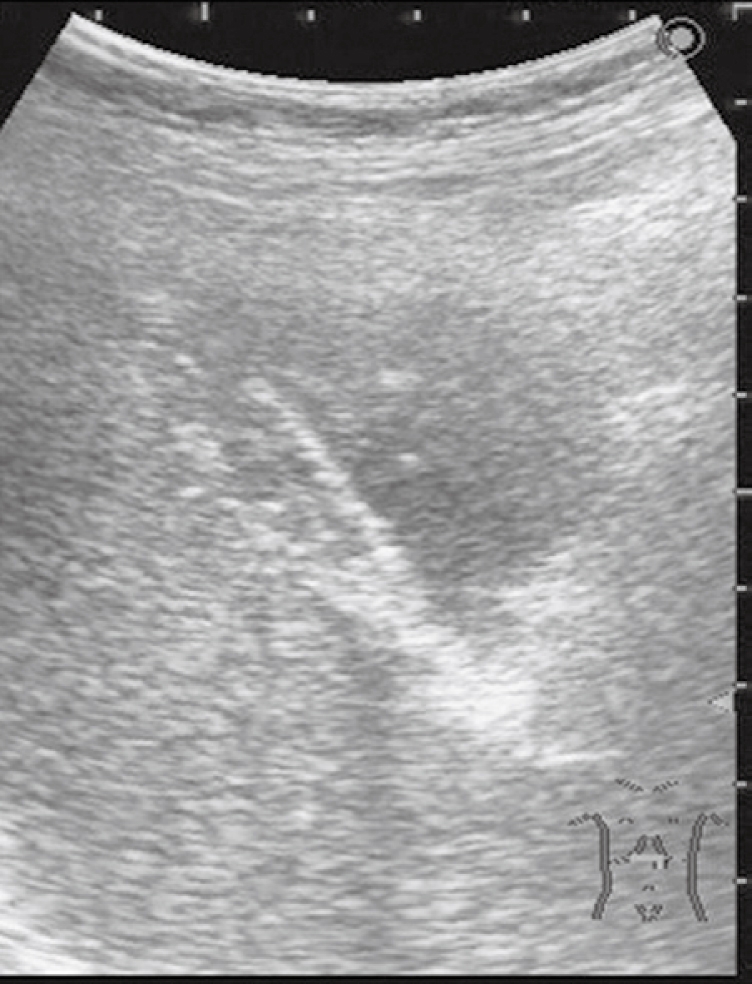

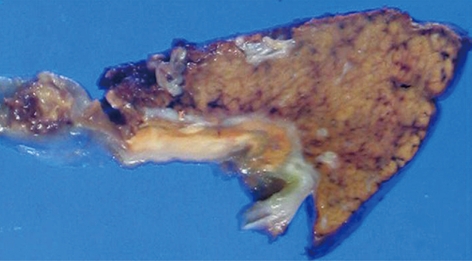

A 76-year-old man receiving treatment for rheumatoid arthritis with prednisolone 7.5 mg/d underwent blood examination in a routine checkup. An increased serum level of γ-glutamyltranspeptidase was found. He received abdominal ultrasonography for further examination. It showed an irregular thickening of the gallbladder wall on the hepatic side (Figure 1). No gallstones were detected. A CT scan also revealed an irregular thickening of the wall of the gallbladder body on the hepatic side. The border between the thickened gallbladder wall and liver parenchyma was indistinct (Figure 2A and B). There was no dilatation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct. No lymphadenopathy was detected. FDG-PET/CT scan showed increased activity in the thickened wall of the gallbladder. The increased uptake area appeared to extend into the liver parenchyma (Figure 2C and D). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed no abnormality of the biliary tract including the cystic duct. An anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction was not found. The result of laboratory examination showed no significant abnormality except for an increased serum level of γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (207 IU/L). C-reactive protein (CRP) was within the normal range (0.09 mg/dL). Tumor markers [carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen (CA19-9), and DUPAN2] were not elevated. We diagnosed the lesion preoperatively as a gallbladder carcinoma with direct invasion to the liver bed. We performed subsegmentectomy of the liver S4a + S5 and lymph node dissection of the hepatoduodenal ligament without extrahepatic bile duct resection. Gross examination of the specimen demonstrated no obvious tumor on the mucosa of the gallbladder. There were no gallstones and only a small amount of biliary sludge in the gallbladder. A yellowish tumor about 2 cm in diameter was observed between the mucosa of the body of the gallbladder and the liver parenchyma in the cut specimen (Figure 3). Pathological examination revealed a XGC with no evidence of malignancy. The postoperative course was uneventful. He is now in good health 8 mo after surgery.

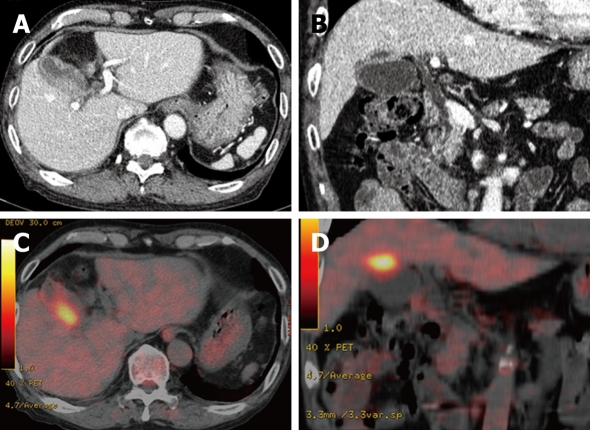

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasonography showed an irregular thickening of the gallbladder wall on the hepatic side. No gallstones were detected.

Figure 2.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). A, B: Abdominal CT scan revealed an irregular thickening of the wall of the gallbladder body on the hepatic side. The border between the thickened gallbladder wall and liver parenchyma was indistinct; C, D: FDG-PET/CT scan showed increased activity in the thickened wall of the gallbladder. The increased uptake area appeared to extend into the liver parenchyma.

Figure 3.

Cut surface of the specimen. A yellowish tumor about 2 cm in diameter was observed between the mucosa of the body of the gallbladder and the liver parenchyma in the cut specimen.

DISCUSSION

XGC is an unusual inflammatory disease of the gallbladder manifested by abnormal thickening of the wall. It was first reported and named by McCoy[6] in 1976 and described as a distinct pathological condition by Goodman and Ishak[7] in 1981. It is a variant of cholecystitis characterized by intense acute or chronic inflammation, severe proliferative fibrosis with formation of multiple yellow-brown intramural nodules and foamy histiocytes. It is speculated that XGC may result from extravasation of bile into the gallbladder wall with involvement of Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses or through a small ulceration in the mucosa. The inflammatory process often extends into neighboring organs, such as the liver, omentum, duodenum, and colon[6–12]. The clinical importance of XGC lies in the fact that it can be confused radiologically with a gallbladder carcinoma. Several reports demonstrated the radiological features of XGC. However, as some are nonspecific, it is often difficult to distinguish XGC from gallbladder carcinoma by the conventional imaging techniques of ultrasonography, CT and MRI[13–18]. Moreover, the fact that XGC can infrequently be associated with gallbladder carcinoma[19,20] makes the differentiation more difficult. Consequently, patients with XGC have sometimes undergone excessive surgical resection with preoperative diagnosis of advanced gallbladder carcinoma[21,22].

Recently, several reports have demonstrated that FDG-PET is useful in differentiating between benign and malignant lesions in the gallbladder. They reported the sensitivity and specificity of FDG-PET for the diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma as 75%-100% and 75%-89%, respectively[1–5]. However, 18F-FDG is not specific for malignant lesions and can accumulate in inflammatory lesions with increased glucose metabolism. Indeed, false-positive results in benign lesions, including chronic cholecystitis, tuberculosis, and adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder have been reported[4,23,24]. Nishiyama et al[25] evaluated the correlation between CRP and 18F-FDG uptake in gallbladder lesions. They reported that the specificity of FDG-PET for the diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma was 80% in the group with normal CRP levels; on the other hand, it decreased to 0% in the group with elevated CRP levels. They recommended FDG-PET for patients with normal CRP levels to differentiate between malignant and benign lesions. In our case, although the patient had no obvious symptoms, such as fever and abdominal pain, and the laboratory data showed no significant inflammatory reaction, such as increased white blood cell counts and elevated CRP level throughout his clinical course, FDG-PET examination resulted in a false-positive diagnosis. It was speculated that the inflammatory reaction in the gallbladder might have been concealed by the effect of the steroid he had daily taken for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. From now on, FDG-PET may be applied for the diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma more frequently. We should consider the possibilities of false-positive results as a result of inflammatory lesions, because of the frequent occurrence of inflammatory diseases in the gallbladder.

Peer reviewers: Masayuki Ohta, MD, Department of Surgery I, Oita University Faculty of Medicine, 1-1 Idaigaoka, Hasama-machi, Oita 879-5593, Japan; David Cronin II, MD, PhD, FACS, Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Yale University School of Medicine, 330 Cedar Street, FMB 116, PO Box 208062, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8062, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Koh T, Taniguchi H, Yamaguchi A, Kunishima S, Yamagishi H. Differential diagnosis of gallbladder cancer using positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-labeled fluoro-deoxyglucose (FDG-PET) J Surg Oncol. 2003;84:74–81. doi: 10.1002/jso.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez-Fernández A, Gómez-Río M, Llamas-Elvira JM, Ortega-Lozano S, Ferrón-Orihuela JA, Ramia-Angel JM, Mansilla-Roselló A, Martínez-del-Valle MD, Ramos-Font C. Positron-emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose for gallbladder cancer diagnosis. Am J Surg. 2004;188:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson CD, Rice MH, Pinson CW, Chapman WC, Chari RS, Delbeke D. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging in the evaluation of gallbladder carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oe A, Kawabe J, Torii K, Kawamura E, Higashiyama S, Kotani J, Hayashi T, Kurooka H, Tsumoto C, Kubo S, et al. Distinguishing benign from malignant gallbladder wall thickening using FDG-PET. Ann Nucl Med. 2006;20:699–703. doi: 10.1007/BF02984683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrowsky H, Wildbrett P, Husarik DB, Hany TF, Tam S, Jochum W, Clavien PA. Impact of integrated positron emission tomography and computed tomography on staging and management of gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2006;45:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCoy JJ Jr, Vila R, Petrossian G, McCall RA, Reddy KS. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Report of two cases. J S C Med Assoc. 1976;72:78–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5:653–659. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houston JP, Collins MC, Cameron I, Reed MW, Parsons MA, Roberts KM. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1030–1032. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon AH, Matsui Y, Uemura Y. Surgical procedures and histopathologic findings for patients with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladefoged C, Lorentzen M. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. A clinicopathological study of 20 cases and review of the literature. APMIS. 1993;101:869–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy AD, Murakata LA, Abbott RM, Rohrmann CA Jr. From the archives of the AFIP. Benign tumors and tumorlike lesions of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Radiographics. 2002;22:387–413. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.2.g02mr08387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang T, Zhang BH, Zhang J, Zhang YJ, Jiang XQ, Wu MC. Surgical treatment of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: experience in 33 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:504–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parra JA, Acinas O, Bueno J, Güezmes A, Fernández MA, Fariñas MC. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: clinical, sonographic, and CT findings in 26 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:979–983. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.4.1740979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chun KA, Ha HK, Yu ES, Shinn KS, Kim KW, Lee DH, Kang SW, Auh YH. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: CT features with emphasis on differentiation from gallbladder carcinoma. Radiology. 1997;203:93–97. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim PN, Lee SH, Gong GY, Kim JG, Ha HK, Lee YJ, Lee MG, Auh YH. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: radiologic findings with histologic correlation that focuses on intramural nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:949–953. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.4.10587127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ros PR, Goodman ZD. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis versus gallbladder carcinoma. Radiology. 1997;203:10–12. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatakenaka M, Adachi T, Matsuyama A, Mori M, Yoshikawa Y. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: importance of chemical-shift gradient-echo MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2233–2235. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shuto R, Kiyosue H, Komatsu E, Matsumoto S, Kawano K, Kondo Y, Yokoyama S, Mori H. CT and MR imaging findings of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: correlation with pathologic findings. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:440–446. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1931-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HS, Joo KR, Kim DH, Park NH, Jeong YK, Suh JH, Nam CW. A case of simultaneous xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis and carcinoma of the gallbladder. Korean J Intern Med. 2003;18:53–56. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2003.18.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benbow EW. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis associated with carcinoma of the gallbladder. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:528–531. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.65.766.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spinelli A, Schumacher G, Pascher A, Lopez-Hanninen E, Al-Abadi H, Benckert C, Sauer IM, Pratschke J, Neumann UP, Jonas S, et al. Extended surgical resection for xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking advanced gallbladder carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2293–2296. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i14.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enomoto T, Todoroki T, Koike N, Kawamoto T, Matsumoto H. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking stage IV gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1255–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramia JM, Muffak K, Fernández A, Villar J, Garrote D, Ferron JA. Gallbladder tuberculosis: false-positive PET diagnosis of gallbladder cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6559–6560. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maldjian PD, Ghesani N, Ahmed S, Liu Y. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder: another cause for a "hot" gallbladder on 18F-FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:W36–W38. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Fukunaga K, Kimura N, Miki A, Sasakawa Y, Wakabayashi H, Satoh K, Ohkawa M. Dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET for the evaluation of gallbladder carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]