Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a potential lethal disease. At present time no evidence based intervention reduces mortality. The pathophysiology of ARDS include intraalveolar fibrin deposition, hyperinflammation and reduced cellular host defense in the airspace. The normal lung activates protein C (PC) to activated protein C (APC), in contrast to the ARDS lung where the PC-APC axis is disrupted. The lungs have targets for inhaled APC as illustrated by a patient case with ARDS, unresponsive to conventional therapy. After inhalation of 190 μg/kg of APC (Drotrecogin alpha activated) three times a day for seven days, a clear reduction in infiltrates on chest X-ray and a 138% increase in oxygenation capacity as reflected by the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was brought about. The patient, however, died later after cardiac arrest after suspected recurrence of the T-cell lymphoma. No local or systemic adverse effects was found related to the iAPC, during, after or at the time of death. It is suggested based on existing studies and the presented case that inhaled APC is a new treatment option in patients with ARDS – a hypothesis which should be substantiated in a larger series of ARDS patients.

Keywords: ARDS, activated protein C inhalation, pulmonary hemostasis, pulmonary host defense

Introduction

Despite improvements in ventilation strategies, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is the most severe form of acute lung injury (ALI), is associated with 40% (Girard and Bernard 2007) and a 80% mortality in mechanically ventilated hematological patients (Pène et al 2006).

Alveolar fibrin deposition is an important feature of ARDS. The alveolar epithelium is capable of initiating intra-alveolar coagulation following exposure to inflammatory stimuli and may thus contribute to intra-alveolar fibrin deposition in ARDS (Bastarache et al 2007). The mechanisms that contribute to disturbed alveolar fibrin turnover are localized tissue factor-mediated thrombin generation and depression of bronchoalveolar urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA)-mediated fibrinolysis caused by the increase of plasminogen activator inhibitors (Schultz et al 2006). Furthermore, a reduced supply of uPA inhibits lung epithelial cell function, since uPA has been shown to activate major intracellular signaling pathways such as tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat3 (Shetty et al 2006). Further increased alpha 2-antiplasmin levels shift the alveolar hemostatic balance towards a procoagulant state (Günther et al 2000).

The natural protein C anticoagulant pathway is a vital system that limits the activation of hemostasis and has anti-inflammatory effects (Hancock et al 1995; Dahlback and Villoutreix 2006; Esmon 2006; Mosnier et al 2007). The alveolar epithelium may therefore modulate intra-alveolar fibrin deposition through activation of protein C.

In inflammatory lung disease the pulmonary host defense is downregulated, as observed in ARDS (Grissell et al 2007).

It is therefore imperative that a new adjunctive intervention in ARDS does not further interfere with the immunocompetent cells of the lungs, ie, with alveolar macrophages or recruited neutrophils. Activated neutrophils accumulate in the lungs during severe infection and inflammation and further contribute to pulmonary dysfunction and mortality (Abraham 2003).

These well described pathophysiological aspects of acute pulmonary inflammation in ARDS with fibrin formation, proinflammatory cytokine production, pulmonary cellular host defense, and neutrophil recruitment are all potential targets of a new treatment paradigm such as inhaled APC.

We describe here for the first time the effect of inhaled APC in a patient with severe ARDS.

Patient history

A 48-year-old woman was treated with chemotherapy for a T-cell lymphoma present in mediastinum, bone marrow, retroperitoneum, and in all peripheral lymph node regions. After five courses of chemotherapy, a partial response with reduction in size of the lymphomas was noted.

While neutropenic after the last course of chemotherapy, she developed fever and clinical signs of pneumonia with lung infiltrates on chest X-ray. One week earlier, she was found to be Epstein barr virus (EBV)–PCR positive in peripheral blood with a high titer (520,000 copies/mL).

The patient subsequently developed respiratory insufficiency and was intubated and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where she was mechanically ventilated. At the same time, the EBV-titer had dropped spontaneously to 100,000 copies/mL, but when a suspected lymphoproliferative disorder induced by EBV was indicated, the patient was treated with anti-CD-20 antibody (Mabthera).

The patient fulfilled the criteria for severe ARDS with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 55 mmHg and chest X ray with diffuse infiltrates. At ICU admittance she was diagnosed with septic shock in need of noradrenaline (NA) infusion combined with methylprednisolone infusion as a shock reversal therapy.

On ICU admission the patient had multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) with respiratory and hemodynamic failure, and liver and renal dysfunction. Administration of broad spectrum antibiotics began. On day 2 in the ICU, the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was unchanged and the patient was still in septic shock. Infectious biomarkers increased but no infectious microorganism was identified at any time.

Lung mechanics were dominated by severely reduced compliance irrespective of any lung protective ventilator setting or recruitment procedures including positioning in a prone position or administration of prostacycline. The optimal ventilator setting was pressure controlled mode with a PEEP 10 cm H2O and pressure level 25 cm H2O.

Blood gases throughout were characterized by respiratory acidosis with a pH = 7.29. Systemic steroid administration had no effect on pulmonary function.

Because of the patient’s acute life-threatening state as a result of severe hypoxemia and the lack of response to conventional intervention, an experimental therapy with inhalation of activated protein C (APC (drotrecogin alpha activated [Xigris®, Eli Lilly, USA]) was commenced on day 4. An institutional review board (IRB) of the National University Hospital of Copenhagen consented to initiate the intervention which was also accepted by the patient’s husband after informed consent. A dose schedule of 190 μg APC/kg 3 times a day was administered via a micropump nebulizer (Aeroneb®) which minimizes drug inactivation, in contrast to jet and ultrasound nebulizers which apply heat and shear stress.

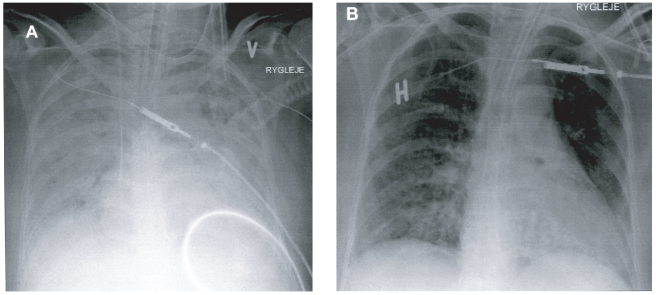

The treatment was scheduled to last 7 days, ie, 21 doses in total. After 4 days (ICU day 8) there was a clear resolution of the infiltrates on chest X ray and of the PaO2/FiO2 ratio, which increased from 55 to 83 mmHg. After 6 days the NA infusion was weaned off and the chest film showed further reduction of infiltrates. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio was further increased to 131 mmHg and then to 155 mmHg at the end of inhalation, with APC corresponding to a 138% increase (see Figure 1). After 7 days the renal and liver dysfunction was reduced and a stable circulation without need of vasopressures was obtained.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray of the patient at the start of the inhalation of APC (A) and after 7 days of inhalation with APC (B).

No adverse effects of the APC inhalation therapy were observed and specifically no “bloody” lavage fluid was seen from the tracheal tube. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and a transbronchial needle biopsy was performed in the ICU on day 14. The biopsy showed diffuse alveolar inflammation corresponding to the organizing phase of diffuse alveolar damage, and signs of bronchiolitis affecting the bronchioli. There was no evidence of lymphoproliferative disease in the lung biopsy. BAL fluid cultures were negative for bacteria, yeast, mold, and virus. On day 16, a CT scan of the abdomen showed new mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. In spite of the temporary clinical improvement with improved oxygenation capacity and opacities on chest X-ray, the patient died in the ICU on day 22 from cardiac arrest. Postmortem section was not granted by her husband.

Discussion

Management of ARDS is difficult due to the frequently life-threatening hypoxemia (Suter 2006). For many years ARDS has been treated with corticosteroids, an approach which has now been shown to be disappointing (The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network 2006). In this patient, however, the corticosteroids were administered as a shock-reversal therapy and not as a symptomatic ARDS therapy. Further symptomatic intervention in ARDS has been the subject of many other randomised studies including treatment options such as antioxidants, inhaled surfactant and vasodilators like nitric oxide, and conservative fluid management of these critically ill patients. These interventions were unsuccessful in reducing the mortality of this potentially lethal disease (Wheeler and Bernard 2007). In spite of therapy to treat any underlying causative factor, standard symptomatic interventions in ARDS with lung protective ventilation, lung recruitment, use of an inhaled vasodilator with prostacyclin (PGI2), and positioning in the prone position, the patient did not respond in respect to respiratory failure or oxygenation capacity. The ARDS condition also failed to respond to systemic steroid therapy. The APC in the present case history was not administered because Severe Sepsis was indicated, but as an experimental therapy for severe pulmonary dysfunction. Since this is a “first in man” therapy, and no evidence based therapy for ARDS exists (Wheeler and Bernard 2007), an experimental attempt was initiated in order to modify or treat the diffuse lung injury. The therapy with inhaled APC for seven days seemed to demonstrate a clear response, with reduction in opacities on chest X ray and with a 138% increase in oxygenation capacity on day 7 as reflected by the PaO2/FiO2 ratio.

This patient died suddenly from a cardiac arrest. Recurrence of malignant lymphoma may have contributed to this event. Another component of the negative outcome might have been the result of initiating the inhalation with APC at a too advanced and less responsive phase of the ARDS course. At the time of death, there was no systemic or local pulmonary adverse effects of iAPC, ie, no signs of bleeding systemically or locally in the lung, ie, alveolar hemorrhage was not present.

ARDS and APC

Endogenous protein C can be activated by thrombomodulin (TM) in the distal airways as well as in the microcirculation (Dahlback and Villoutreix 2006; Esmon 2006; Mosnier et al 2007). In the periphery of the lung an epithelial protein C receptor (EPCR), located on alveolar type I and II cells in the small airways mediates the endogenous pulmonary APC response (Wang et al 2007). Inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) causes suppression of the PC pathway, as indicated by increased concentration of soluble TM and decreased concentration of PC and APC in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (Maris et al 2007).

In a study of 45 patients with ALI/ARDS, resulting from septic and nonseptic causes, the concentration of TM in BALF was more than twofold higher than simultaneous plasma levels, suggesting that local production in the lung, and increased edema fluid TM level, was associated with worse clinical outcomes (Ware et al 2003). Deficient intra-alveolar activation of protein C may aggravate the severity of ARDS by enhancing fibrin deposition via localized pulmonary tissue factor-mediated thrombin generation, and depression of bronchoalveolar urokinase plasminogen activator-mediated fibrinolysis, caused by the increase of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 (Schultz et al 2006). Therefore, the protein C system may be a potential therapeutic target, using supplementary inhalation of APC in patients with ALI/ARDS to compensate for the innate APC deficiency.

In mice exposed to LPS, inhalation of APC was associated with a dose-dependent decrease in coagulation, inflammation markers in BAL fluid, reduced protein leakage into the alveolar space and improved lung function (Slofstra et al 2006).

These findings provide new evidence that inhaled activated protein C may modify alveolar fibrin deposition in ARDS (Suter 2006) as seen in the positive clinical response in the present patient.

Intravenous vs inhalation administration of APC

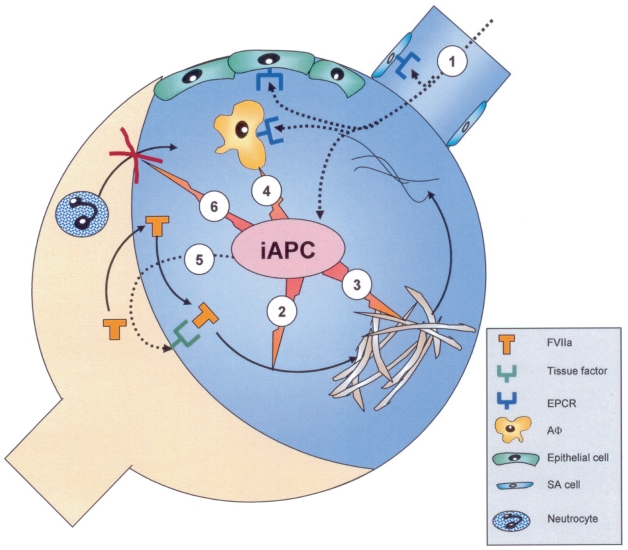

Intravenously administered recombinant human activated protein C (rhAPC) in acute lung injury after bacterial challenge significantly attenuated the fall in PaO2/FiO2 ratio, improved the lung mechanics and limited the induced lung tissue injury (van der Poll et al 2005). The APC, however, most likely exerts its effect both through inhibition of coagulation, and by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis, by binding to its receptor EPCR, located in the airspaces. This result implies that the multiple targets for APC in ARDS are located in the airspaces (see Figure 1).

In order to obtain a sufficiently high alveolar concentration of APC, the IV dose rate must be sufficiently high, taking into account several factors. In order to reach sufficient alveolar APC concentration, the IV dosing must overcome the inactivation of the two serpins, alpha1-anti trypsin and the protein C inhibitor (PCI), and also the very short half-life of 13 minutes of APC when administered intravenously (Bernard et al 2001a). Furthermore, the APC molecule is quite large, ie, 55 kDa with 461 amino acids with a corresponding high diffusion barrier across the alveolo-capillary membrane to the airway receptors. All these factors limit the efficiency of an IV dose when the target is the airways. Once the IV dose reaches the air space, APC is further metabolised by alveolar proteolytic enzymes. It therefore seems rational also to inhale APC when the therapeutic target is the lung airspaces in acute respiratory injury like ARDS, in order to overcome the adverse effects of IV dosing.

The dosing of inhaled APC in the present patient case was based on the same dosing regime as in the PROWESS study (Bernard et al 2001b) of 24 μg/kg/hr, corresponding to a total dose for 24 hours of 576 μg/kg; divided into three inhalation doses. This treatment corresponds to a single inhaled dose of 190 μg/kg rAPC.

We predicted that a dose of 190 μg/kg per inhalation, would give rise to a suitably lower alveolar concentration, corresponding to 20% of the inhaled APC dose deposited using the micropump nebulizer Aeroneb (Dubus et al 2005). The metabolism of APC has been well described; however, the intrapulmonary metabolism after inhaled APC has not been elucidated.

An increased metabolism of APC is likely in inflammatory pulmonary conditions, because elevated levels of neutrophil, and macrophage-derived proteolytic enzymes like neutrophil elastase and cathepsin, have been documented in ARDS patients (Sallenave et al 1999). Furthermore, because the neutralizing protein C Inhibitor (PCI) is a smaller molecule, it readily diffuses into the alveolar space where it subsequently neutralizes APC, a process which is enhanced in inflammatory lung disease, as revealed by increased concentrations of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid levels of TAFI and PCI (Fujimoto et al 2003). A high APC dose would give rise to a ‘spill over’ of drug to the systemic circulation with detectable increase in APTT. Such an increase however could not be demonstrated in the present patient. In short, it seems that an inhaled dose of 190 μg/kg in each inhalation is a realistic moderate dose. In a systematic proof of concept study, APC kinetics will be included.

We chose to extend the dose length from the 4-day dose scheme applied in the prowess study (Bernard et al 2001b) to 7 days in the present patient, taking into account the ongoing pathophysiology of the ARDS and the relatively long recovery time of ARDS.

In the present study a micropump nebulizer was selected, because it has been shown to produce aerosolized protein samples which retain both structural integrity and biological activity (Oette et al 2004). This decision is in keeping with the study of aerosolized APC using the same nebulizer where coagulation factors like TAT complex and the cytokines TNF and IL-6 were reduced, corresponding to a preserved activity of APC aerosol (Slofstra et al 2006). It is therefore likely that the inhaled APC retains its activity after aerosolization using a micropump nebulizer.

APC and diffuse lung injury (DLI)

Pulmonary complications like noninfectious diffuse lung injury (DLI) in hematological patients like the patient case – a severe form of ARDS – has a high incidence in hematological patients (Krowka et al 1985). The histopathology of DLI includes diffuse epithelial alveolar damage with hyaline membranes, lymphocytic bronchiolar inflammation and bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP) (Watkins et al 2005). The survival rate for critically ill hematological patients with DLI requiring mechanical ventilation has been reported to be well below 20% (Shorr et al 1999; Pène et al 2006). This patient died suddently from a cardiac arrest; both the ARDS and the malignant lymphoma may have contributed to this event. Another component of the negative outcome was the initiation of the inhalation with APC at a late and less responsive phase of the ARDS course. At the time of death, there was no systemic or local pulmonary adverse effects of iAPC with no signs of bleeding systemically or locally in the lung, ie, alveolar hemorrhage was not present.

This patient had a component of bronchiolitis as seen in the lung biopsy. The pulmonary clinical response in the present case could partially be explained by the immunomodulatory effect of activated protein C, which has been shown to reduce the peribronchiolar lymphocytic migration (Feistritzer et al 2006). This effect matches the findings of an inhibition of immunologic and inflammatory responses induced by Th2 produced cytokines in a mouse model of asthma after intratracheally administered APC (Yuda et al 2004).

Pulmonary host defense and APC

The pulmonary host defense is reduced in ARDS with increased apoptosis gene expression and reduced TLR gene mRNA expression in airway cells (Grissell et al 2007). Mechanical ventilation with high FiO2, results in further impairment in pulmonary innate immunity through suppression of local GM-CSF expression of alveolar epithelial cells due to hyperoxic stress (Baleeiro et al 2006). It is therefore important when introducing a novel therapy such as aerosolized APC, that it does not further interfere with the pulmonary host defense.

Inhalation of APC interacts with the inflammatory and coagulation, a response which may impede the primary host defense mechanisms (Opal and Esmon 2003). Prior to introduction of a new therapy like inhalation of APC, evaluation of host defense, such as phagocytotic activity of alveolar macrophages, apoptosis of cellular host defense and expression of alveolar recognition receptors, ie, Toll-like receptors must be taken into account. An in-vitro study of activated protein C showed that the lifespan of human macrophages was prolonged, with unaltered phagocytotic function towards both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and persistent adherence capabilities to LPS stimulated cells, promoting and maintaining antimicrobial properties while limiting damage to host tissue (Stephenson et al 2006). There is no documentation of the interference of APC with TLR receptor expression, but in the study of LPS challenge, APC reduced mortality in murine endotoxemia and models of severe sepsis (Griffin et al 2007) and in the study of pneumonia, APC did not seem to interact with bacterial clearance (Choi et al 2007). This study also showed that administration of APC improved the outcome for patients with severe sepsis in spite of positive cultures in a majority of the included septic patients (Bernard et al 2001b). Finally APC has an antiapoptotic effect (Esmon 2006) which is considered an essential therapeutic target treating infectious conditions (Doreen et al 2007).

Accumulation of activated neutrophils into the airspaces during severe infection contributes to organ dysfunction in ARDS. It has been shown that APC modulates the neutrophil responses due to the expression of an APC receptor on these cells (Sturn et al 2003), and that intravenous APC reduced leukocyte accumulation, and neutrophil chemotaxis into the airspaces without inducing immunosuppression (Nick et al 2004).

Therefore, in general APC does not seem to have a negative affect on pulmonary host defense. On the contrary, inhaled APC most likely represents a valuable new treatment which reduces severity of ARDS, but without interfering with the pulmonary host defense.

Conclusion

A new symptomatic therapy, involving intrapulmonary administration of aerosolized APC is proposed and illustrated by a case with a positive pulmonary clinical response. No adverse effects could be registered during the 7-day therapy. From a theoretical viewpoint, inhaled APC with its anticoagulatory, profibrinolytic, antiinflammatory and antiapoptotic effect, including reduced neutrophil recruitment into the airspaces, has all the essential properties to counteract the pathophysiological changes seen in ARDS. Furthermore, inhaled APC seems not to interfere with the pulmonary host defense. Therefore we suggest that ARDS is best treated from the “air side” with aerosolized APC, because the innate intrapulmonary PC-APC axis is disrupted in inflammatory lung conditions like ARDS and the multiple effects of iAPC are mediated via the targets in the airspaces. We conclude that inhaled APC could become a new treatment option in patients with ALI or ARDS. This hypothesis should be substantiated in a study of a larger series of ARDS patients.

Key messages

– Inhaled APC has multiple effects to counteract the well described pathophysiological ARDS changes, as illustrated in a patient case.

– It seems that inhaled APC does not interfere with pulmonary host defense.

– Inhaled APC might be a new ideal adjunctive intervention in ARDS combined with therapy of underlying disease, a suggestion which should be substantiated in a larger series of patients.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the potential multiple effects of inhaled activated protein C (iAPC) in ARDS in relation to the underlying pathophysiology of ARDS. Inhaled APC (1) inhibits coagulation (Factor Va and VIIIa) (2) and enhances fibrinolysis (3). Further iAPC has an anti-inflammatory effect and anti-apoptotic effect exerted via its APC receptor (EPCR) on the alveolar macrophage, epithelial cell and finally at the site of small airways (4) and reduces tissue factor expression via inhibition of the transnuclear NFKB translocation (5). Finally iAPC inhibits neutrocyte recruitment from the circulation to the airspaces (6) without interfering with their host function. The numbers 1–6 refer to the multiple points of action of iAPC.

Abbreviations: AF, Alveolar macrophage; EPCR, Epithelial protein C receptor; FVII, Coagulation factor VII; SA cell, Mucosal cell of small airways.

Abbreviations

- APC

Activated protein C

- ALI

Acute lung injury

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- BALF

BAL fluid

- BOOP

Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia

- CHOEP

Chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, oncovin, etopophos, and prednisone

- DLI

Diffuse lung injury

- EBV

Epstein barr virus

- ERPC

Endothelial protein C receptor

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- iAPC

Inhaled APC

- FiO2

Inspired fractional oxygen content

- IRB

Institutional review board

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MODS

Multi-organ dysfunction disease

- NFKB

Nuclear factor kappa-B

- PaO2

Partial pressure of oxygen

- PAI-1

Plasminogen activator-1

- PC

Protein C

- PCI

Protein C Inhibitor

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- TM

Thrombomodulin

- TLR

Toll-like receptors

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

LH has shares in the pharmacompany Drugrecure, Copenhagen, Denmark, which holds a patent related to the inhaled activated protein C. LH has, however, not received reimbursements, fees, funding, from any organization relating to the content or the preparation of this manuscript. LH declares that he has no other competing interests. JSA, JDN, BD, and HS declare that they have no competing financial interests related to the preparation or the content of the manuscript. The study was initated based on the original idea of LH. LH also developed the study design and coordinated its implementation. LH, JSA, HS, BD, and JDN participated in the interpretation and discussion of results and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S195–199. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baleeiro CE, Christensen PJ, Morris SB, et al. GM-CSF and the impaired pulmonary innate immune response following hyperoxic stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1246–55. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00016.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastarache JA, Wang L, Geiser T, et al. The alveolar epithelium can initiate the extrinsic coagulation cascade through expression of tissue factor. Thorax. 2007;62:608–16. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard GR, Ely EW, Wright TJ, et al. Safety and dose relationship of recombinant human activated protein C for coagulopathy in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2001a;29:2051–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Recombinant human protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study group. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001b;344:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi G, Hofstra JJ, Roelofs JJ, et al. Recombinant human activated protein C inhibits local and systemic activation of coagulation without influencing inflammation during Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in rats. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1362–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000261888.32654.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlback B, Villoutreix BO. Regulation of blood coagulation by the protein C anticoagulant pathway: novel insights into structure-function relationships and molecular recognition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1311–20. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168421.13467.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doreen E Wesche-Soldato, Ryan Z, et al. The apoptotic pathway as a therapeutic target in sepsis. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8(4):493–500. doi: 10.2174/138945007780362764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubus JC, Vecellio L, De Monte M, et al. Aerosol deposition in neonatal ventilation. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:10–14. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000156244.84422.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. Inflammation and the activated protein C anticoagulant pathway. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;(Suppl 1):49–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feistritzer C, Mosheimer BA, Sturn DH, et al. Endothelial protein C receptor-dependent inhibition of migration of human lymphocytes by protein C involves epidermal growth factor receptor. J Immunol. 2006;176:1019–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto H, Gabazza EC, Hataji O, et al. Thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor and protein C inhibitor in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1687–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-905OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard TD, Bernard GR. Mechanical ventilation in ARDS: a state-of-the-art review. Chest. 2007;131:921–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JH, Fernández JA, Gale AJ, et al. Activated protein C. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissell TV, Chang AB, Gibson PG. Reduced toll-like receptor 4 and substance P gene expression is associated with airway bacterial colonization in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:380–5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther A, Mosavi P, Heinemann S, et al. Alveolar fibrin formation caused by enhanced procoagulant and depressed fibrinolytic capacities in severe pneumonia: comparison with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:454–62. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9712038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock WW, Grey ST, Hau L, et al. Binding of activated protein C to a specific receptor on human mononuclear phagocytes inhibits intracellular calcium signaling and monocyte-dependent proliferative responses. Transplantation. 1995;60:1525–32. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199560120-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krowka MJ, Rosenow EC, 3rd, Hoagland HC. Pulmonary complications of bone marrow transplantation. Chest. 1985;87:237–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris NA, Vos AF, Bresser P, et al. Salmeterol enhances pulmonary fibrinolysis in healthy volunteers. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:57–63. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000249827.29387.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnier LO, Zlokovic BV, Griffin JH. The cytoprotective protein C pathway. Blood. 2007;109:3161–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nick JA, Coldren CD, Geraci MW, et al. Recombinant human activated protein C reduces human endotoxin-induced pulmonary inflammation via inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis. Blood. 2004;104:3878–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oette SM, Gedeon CR, Kowalczyk TH, et al. Aerosols of compacted DNA nanoparticles retain structural integrity and biological activity. Mol Ther. 2004;9:S190. [Google Scholar]

- Opal SM, Esmon CT. Bench-to-bedside review: functional relationships between coagulation and the innate immune response and their respective roles in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Crit Care. 2003;7(1):23–38. doi: 10.1186/cc1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pène F, Aubron C, Azoulay E, et al. Outcome of critically ill allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: a reappraisal of indications for organ failure supports. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:643–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallenave JM, Donnelly SC, Grant IS. Secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor is preferentially increased in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1029–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13e16.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz MJ, Haitsma JJ, Zhang H, et al. Pulmonary coagulopathy as a new target in therapeutic studies of acute lung injury or pneumonia – a review. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:871–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty S, Rao GN, Cines DB, et al. Urokinase induces activation of STAT3 in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:772–80. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00476.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorr AF, Moores LK, Edenfield WJ, et al. Mechanical ventilation in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: can we effectively predict outcomes. Chest. 1999;116:1012–18. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slofstra SH, Groot AP, Maris NA, et al. Inhalation of activated protein C inhibits endotoxin-induced pulmonary inflammation in mice independent of neutrophil recruitment. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:740–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson DA, Toltl LJ, Beaudin S, et al. Modulation of monocyte function by activated protein C, a natural anticoagulant. J Immunol. 2006;177:2115–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturn DH, Kaneider NC, Feistritzer C, et al. Expression and function of the endothelial protein C receptor in human neutrophils. Blood. 2003;102:1499–505. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter PM. Lung Inflammation in ARDS – Friend or Foe? Editorial. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1739–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1671–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll T, Levi M, Nick JA, et al. Activated protein C inhibits local coagulation after intrapulmonary delivery of endotoxin in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1125–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1483OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Bastarache JA, Wickersham N, et al. Novel role of the human alveolar epithelium in regulating intra-alveolar coagulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:497–503. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0425OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LB, Fang X, Matthay MA. Protein C and thrombomodulin in human acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L514–521. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00442.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins TR, Chien JW, Crawford SW. Graft versus host-associated pulmonary disease and other idiopathic pulmonary complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;26:482–89. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-922031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a clinical review. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1553–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuda H, Adachi Y, Taguchi O, et al. Activated protein C inhibits bronchial hyperresponsiveness and Th2 cytokine expression in mice. Blood. 2004;103:2196–204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]