Abstract

Autophagy is an ancient, intracellular degradative system which plays important roles in regulating protein homeostasis and which is essential for survival when cells are faced with metabolic stress. Increasing evidence suggests that autophagy also functions as a tumor suppressor mechanism that harnesses the growth and/or survival of cells as they transition towards a rapidly dividing malignant state. However, the impact of autophagy on cancer progression and on the efficacy of cancer therapeutics is controversial. In particular, although the induction of autophagy has been reported after treatment with a number of therapeutic agents, including imatinib, this response has variously been suggested to either impair or contribute to the effects of anticancer agents. More recent studies support the notion that autophagy compromises the efficacy of anticancer agents, where agents such as chloroquine (CQ) that impair autophagy augment the anticancer activity of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors and alkylating agents. Inhibition of autophagy is a particularly attractive strategy for the treatment of imatinib-refractory chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) since a combination of CQ with the HDAC inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) compromises the survival of even BCR-ABL-T315I+ imatinib-resistant CML. Additional studies are clearly needed to establish the clinical utility of autophagy inhibitors and to identify patients most likely to benefit from this novel therapeutic approach.

Keywords: autophagy, imatinib, resistance, chronic myelogenous leukemia

Autophagy and its role in cancer

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved bulk protein degradative pathway in which double-membraned autophagosome vesicles engulf target proteins or organelles and deliver them to lysosomes where they are degraded. Accordingly, the autophagic response plays important roles in regulating protein and organelle homeostasis. However, this pathway is also essential to generate alternative energy sources during starvation or other states of significant cellular stress (Klionsky and Emr 2000; Yorimitsu and Klionsky 2005). Further, mouse knockout models have demonstrated that autophagy also plays a critical role in mammalian development, where targeted deletion of Beclin-1 leads to mid-gestational embryonic lethality (Yue et al 2003) and where loss of either Atg5 or Atg7, two key players in the ubiquitin-like systems of this pathway, results in perinatal lethality (Kuma et al 2004; Komatsu et al 2005).

Several recent high-profile investigations have established that autophagy also plays important roles in cancer biology. However, exactly how autophagy intersects with cancer development, disease progression, tumor maintenance, and therapeutic responses is controversial. The most significant studies regarding the role(s) of autophagy in cancer were recently reviewed by White and colleagues (Mathew et al 2007). Collectively, studies in this arena indicate that autophagy is a tumor suppressor pathway that holds cancer development in check, by preventing the proliferation of altered cells. For example, mice haploinsufficient for Beclin-1, an established initiator of the autophagy pathway, are tumor prone (Liang et al 1999; Qu et al 2003; Yue et al 2003). Further, allelic loss of Beclin-1 is a frequent event in certain types of solid tumors and genes encoding other autophagy regulators are localized to “hot spots” for deletions in tumors (Aita et al 1999; Liang et al 1999). Thus, impairing the autophagy response may prime cells for oncogenesis and contribute to the intrinsic genetic instability of pre-malignant and cancer cells. Considering this, agents that stimulate autophagy have potential value in cancer chemoprevention.

Paradoxically, it appears that activation of autophagy is detrimental once a cancer has fully developed. In particular, the degradation of cytoplasmic material and organelles by autophagy is essential to prevent bioenergetic failure when tumor cells face nutrient or oxygen deprivation (Lum et al 2005a), which are hallmarks of the tumor microenvironment. Thus, here autophagy would be predicted to promote tumor cell survival and consequently, disease progression (Lum et al 2005b). Indeed, despite their diverse mechanisms of action, many frontline anticancer agents ultimately shut down conventional metabolic pathways due to the cellular stress that they impose, and they thus can stimulate autophagy. Indeed, the induction of autophagy has been observed in malignant cells after treatment with a number of cancer therapeutics including arsenic trioxide, rapamycin, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, tamoxifen, imatinib, and ionizing radiation (Bursch et al 1996; Paglin et al 2001; Kanzawa et al 2003; Shao et al 2004; Takeuchi et al 2005; Ertmer et al 2007). Although some of the these studies have suggested that efficacy of these agents correlates with their ability to stimulate autophagy-mediated cell death, such conclusions need rigorous testing, especially since these modalities also trigger apoptosis. In fact, two recent studies have shown that combining inhibitors of autophagy with alkylating agents or HDAC inhibitors significantly enhances their anticancer activity (Amaravadi et al 2007; Carew et al 2007). Collectively, the majority of investigations have shown that apoptosis is a much more efficient mode of cell death than autophagy-mediated cell killing.

Inhibition of autophagy as a therapeutic strategy for imatinib-refractory CML

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is one of the four most common types of adult leukemia. In contrast to most forms of cancer, the molecular basis of disease development and pathogenesis is very well defined for CML. The underlying cause of CML is the formation of the Philadelphia chromosome due to a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22. This translocation results in the production of the BCR-ABL fusion protein, a tyrosine kinase that controls critical signaling pathways involved in the development and progression of CML. The disease is subdivided into three phases, chronic phase, accelerated phase, and blast crisis, and disease progression can occur over several years.

Treatment of CML was revolutionized by the advent of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec™; Novartis), a targeted agent that inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of BCR-ABL by competing with ATP for binding to the active site of the enzyme. Imatinib is very effective for many CML patients particularly during the chronic phase, yet drug resistance is an emerging problem. Several factors contribute to clinical imatinib resistance, including BCR-ABL overexpression and gene amplification and/or loss-of-function mutations in p53 (Shah et al 2002; Wendel et al 2006). However, the most prevalent cause of drug resistance is the development of missense mutations in BCR-ABL that either precludes the adoption of the inactive conformation of the kinase or that directly interferes with drug binding. A large number of specific mutations have been characterized and tremendous effort has been put forth to develop more effective strategies to treat imatinib-resistant CML patients. Two novel kinase inhibitors, dasatinib (Sprycel™; Bristol-Myers Squibb) and nilotinib (Tasigna™; Novartis), have shown promising clinical activity in some imatinib-refractory patients and both have recently earned FDA approval. Unfortunately, patients with the T315I BCR-ABL mutation do not respond to these new drugs (Kantarjian et al 2006; Talpaz et al 2006).

Given these considerations, a major focus in the field of CML therapy is the development of novel strategies that can effectively treat T315I+ patients. Indeed, a large number of anticancer agents are under investigation for this specific indication. HDAC inhibitors are one such class of drugs that may have utility in the clinical treatment of imatinib-resistant CML. HDAC inhibitors are a fascinating class of anticancer agents, due to their multifaceted mechanisms of action and preferential toxicity for malignant cells, and they have demonstrated promising anticancer activity in a number of pre-clinical and clinical studies (Kelly and Marks 2005). SAHA (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, vorinostat, Zolinza®; Merck) is the most clinically advanced HDAC inhibitor and recently received FDA approval for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) in an oral formulation. SAHA’s anticancer mechanism of action has been reported to include the induction of apoptosis, autophagy, polyploidy, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and growth inhibition (Yu et al 2003; Shao et al 2004; Xu et al 2005; Nawrocki et al 2006).

Due to its ability to provide essential sources of energy, autophagy has been suggested to blunt the efficacy of several pro-apoptotic therapeutic agents. Therefore, drugs that impair autophagy could theoretically potentiate the anticancer efficacy of SAHA and other HDAC inhibitors by disabling this important cell survival mechanism. We recently tested this hypothesis in a cell line model of imatinib resistance and in imatinib-refractory primary CML cells from patients with BCR-ABL mutations, including T315I (Carew et al 2007). Both chloroquine (CQ) and 3-methyladenine (3-MA), two pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy, synergistically increased the killing power of SAHA against imatinib-resistant CML. Furthermore, this therapeutic strategy was also effective in killing T315I-Bcr-Abl-expressing cells lacking p53, and this combination demonstrated a high degree of selectivity, indicating that a therapeutic index can be achieved.

CQ is a weak base and a known lysosomotropic agent that perturbs lysosomal function. Our data indicated that CQ synergizes with SAHA by disrupting the lysosomal membrane permeability of CML cells, which in turn led to the rapid relocalization and accumulation of the lysosomal aspartic protease cathepsin D to the cytosol. Notably, cathepsin D is a key mediator of a lysosomally triggered apoptotic cascade induced by several anticancer agents (Boya et al 2003; Fehrenbacher and Jaattela 2005) and a key substrate of this protease is the antioxidant protein thioredoxin (Trx). Interestingly, the CQ/SAHA combination markedly reduced Trx levels in CML cells, and correspondingly increased ROS (Carew et al 2007), suggesting that a CQ-to-LMP-to-cathepsin D-to-Trx-to-ROS pathway contributes to the demise of imatinib-resistant CML also treated with SAHA.

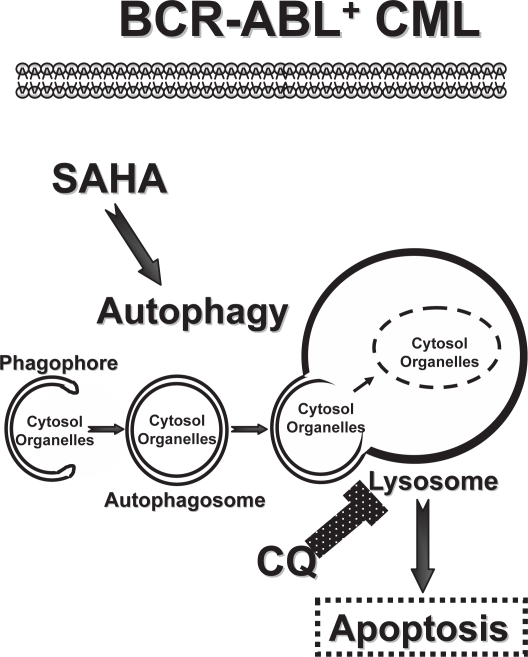

Collectively, these findings indicate that autophagy promotes the survival of CML cells after metabolic stress that is induced by SAHA. Thus, inhibition of autophagy by CQ interferes with this cytoprotective response and augments SAHA’s anticancer activity. A recent study revealed that imatinib stimulates autophagy in a wide variety of cell types, suggesting that this response contributes to the resistance of several tumor types (Ertmer et al 2007). Thus, future investigations are clearly warranted to evaluate the impact of targeting the autophagy pathway on the anticancer activity of imatinib, where one would predict that inhibitors of autophagy such as CQ may also have utility in combination with imatinib (Figure 1). Indeed, inhibition of autophagy as a novel anticancer strategy may have broad applications for a wide variety of refractory malignancies. This concept is further supported by recent studies demonstrating that inhibition of autophagy by CQ in a Myc-driven mouse model of B cell lymphoma delays tumor onset (Maclean et al 2008) and augments the anticancer activity of the alkylating agent cyclophosphamide in established disease (Amaravadi et al 2007). Indeed, clinical trials testing the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in combination with bortezomib, temozolomide, temsirolimus, or other agents have been initiated for various malignancies. The knowledge gained from these trials will provide critical insights into the clinical potential of inhibition of autophagy as a novel anticancer strategy.

Figure 1.

Targeting the autophagy pathway in CML. Imatinib-resistant BCR-ABL+ CML are sensitive to a therapeutic combination of SAHA, a FDA-approved HDAC inhibitor, and CQ, a FDA-approved anti-malarial agent (Carew et al 2007). Here the overall efficacy of SAHA is thought to be compromised by its induction of the autophagy pathway, which is initiated by the formation of double-membraned autophagosomes from vesicular structures coined the phagophore. Autophagosomes deliver their cargo, bulk cytosolic material and organelles, to the lysosome, which degrades the cargo to provide essential building blocks and energy to the CML cell. The lysosomotropic agent CQ compromises lysosomal functions and thus derails the autophagy pathway, augmenting the killing power of SAHA to overcome imatinib resistance provoked by mutations in BCR-ABL and/or p53 (Carew et al 2007).

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; CQ, chloroquine; HDAC, histone deacetylase; SAHA, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid.

Concluding remarks

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved cell survival pathway that is now rightly receiving attention as a regulator of tumor cell biology. Recent investigations have suggested that autophagy is a promising target for pharmacological inhibition in the context of cancer therapy (Carew et al 2007; Amaravadi et al 2007). On the flip side, others have argued that autophagy represents an alternative cell death pathway that contributes to the killing power of certain anticancer agents (Kanzawa et al 2003; Takeuchi et al 2005). Despite these controversies, it is clear that agents such as CQ that inhibit autophagy may have clinical utility in the treatment of imatinib-refractory CML. The observations that imatinib alone induces autophagy, coupled with the evidence that autophagy may play an active role in resistance to anti-cancer agents, mandates the need for additional studies to define whether it represents a novel mechanism of imatinib resistance. It will also be very interesting to assess if imatinib-refractory CML patients have higher basal rates of autophagy than those that respond well to therapy. Hopefully, the knowledge gained from such studies will enable clinicians to use the genetic status of key autophagy regulators to predict therapeutic responses and tailor specific regimens to optimize clinical outcomes for patients with CML, and for those suffering from other resistant malignancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ studies were supported by a grant CA076379 (to JLC) from the National Cancer Institute and by monies awarded by the State of Florida to Scripps-Florida.

Disclosures

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VV, et al. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics. 1999;59:59–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:326–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI28833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Andreau K, Poncet D, et al. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization induces cell death in a mitochondrion-dependent fashion. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1323–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch W, Ellinger A, Kienzl H, et al. Active cell death induced by the anti-estrogens tamoxifen and ICI 164 384 in human mammary carcinoma cells MCF-7. in culture: the role of autophagy. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1595–607. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.8.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Kahue CN, et al. Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr-Abl-mediated drug resistance. Blood. 2007;110:313–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer A, Huber V, Gilch S, et al. The anticancer drug imatinib induces cellular autophagy. Leukemia. 2007;21:936–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbacher N, Jaattela M. Lysosomes as targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2993–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2542–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzawa T, Kondo Y, Ito H, et al. Induction of autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by arsenic trioxide. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WK, Marks PA. Drug insight: Histone deacetylase inhibitors – development of the new targeted anticancer agent suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:150–7. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Emr SD. Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science. 2000;290:1717–21. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–6. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum JJ, Bauer DE, Kong M, et al. Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell. 2005a;120:237–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum JJ, Deberardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Autophagy in metazoans: cell survival in the land of plenty. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005b;6:439–48. doi: 10.1038/nrm1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean KH, Dorsey FC, Cleveland JL, et al. Targeting lysosomal degradation induces p53-dependent cell death and prevents cancer in mouse models of lymphomagenesis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:79–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI33700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:961–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Pino MS, et al. Aggresome disruption: a novel strategy to enhance bortezomib-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3773–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglin S, Hollister T, Delohery T, et al. A novel response of cancer cells to radiation involves autophagy and formation of acidic vesicles. Cancer Res. 2001;61:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1809–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NP, Nicoll JM, Nagar B, et al. Multiple BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations confer polyclonal resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib STI571. in chronic phase and blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Gao Z, Marks PA, et al. Apoptotic and autophagic cell death induced by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:18030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408345102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Kondo Y, Fujiwara K, et al. Synergistic augmentation of rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3336–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel HG, de Stanchina E, Cepero E, et al. Loss of p53 impedes the antileukemic response to BCR-ABL inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7444–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602402103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu WS, Perez G, Ngo L, et al. Induction of polyploidy by histone deacetylase inhibitor: a pathway for antitumor effects. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7832–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 2):1542–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Subler M, Rahmani M, et al. Induction of apoptosis in BCR/ABL+ cells by histone deacetylase inhibitors involves reciprocal effects on the RAF/MEK/ERK and JNK pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:544–51. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.5.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, et al. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]