Abstract

The five known members of the sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor family exhibit diverse tissue expression profiles and couple to distinct G-protein-mediated signalling pathways. S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 receptors are all present in the heart, but the ratio of these subtypes differs for various cardiac cells. The goal of this review is to summarize data concerning which S1P receptor subtypes regulate cardiac physiology and pathophysiology, which G-proteins and signalling pathways they couple to, and in which cell types they are expressed. The available information is based on studies using a lamentably limited set of pharmacological agonists/antagonists, but is complemented by work with S1P receptor subtype-specific knockout mice and sphingosine kinase knockout mice. In cardiac myocytes, the S1P1 receptor subtype is the predominant subtype expressed, and the activation of this receptor inhibits cAMP formation and antagonizes adrenergic receptor-mediated contractility. The S1P3 receptor, while expressed at lower levels, mediates the bradycardic effect of S1P agonists. Studies using knockout mice indicate that S1P2 and S1P3 receptors play a major role in mediating cardioprotection from ischaemia/reperfusion injury in vivo. S1P receptors are also involved in remodelling, proliferation, and differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts, a cell type in which the S1P3 receptor predominates. Receptors for S1P are also present in endothelial and smooth muscle cells where they mediate peripheral vascular tone and endothelial responses, but the role of this regulatory system in the cardiac vasculature is unknown. Further understanding of the contributions of each cell and receptor subtype to cardiac function and pathophysiology should expedite consideration of the endogenous S1P signalling pathway as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor, Heart, Myocytes, Knockout mice, Sphingosine-1-phosphate

1. Introduction

The lysophospholipid, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), is a circulating bioactive lipid metabolite that has been known for many years to induce cellular responses, including proliferation, migration, contraction, and intracellular calcium mobilization.1,2 There is evidence that S1P can function as an intracellular second messenger.3,4 However, several early studies showed that S1P-mediated responses could be blocked by pertussis toxin, which prevents G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) from activating the heterotrimeric G-proteins Gi or Go. These data suggested that S1P was functioning through a GPCR. Now that a family of GPCRs for which S1P is the high affinity ligand has been discovered, it is well accepted that the activation of these receptors is the mechanism by which S1P elicits most of its biological responses.5–7

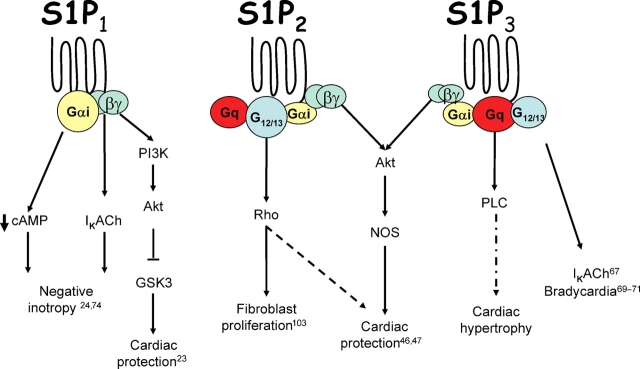

There are currently five receptors for which S1P is the high affinity ligand. All of these are GPCRs. Binding of S1P to the receptor activates specific signalling pathways as a consequence of receptor coupling to selected G-proteins. Biochemical and molecular studies have revealed that there is specificity in the coupling of the different S1P receptor subtypes to various G-proteins. The S1P1 receptor is unique in that it couples exclusively to the Gi protein.8–10 In contrast, the S1P2 and S1P3 receptors couple promiscuously to Gi, Gq, and G12/13 proteins,11–13 whereas the S1P4 and S1P5 receptors couple to both Gi and G12/13 proteins.14–17 Upon activation, the alpha subunit of the heterotrimeric G-protein is released and able to interact with downstream effectors. The effector for the alpha subunit of Gi is adenylate cyclase (which it inhibits); release of beta/gamma subunits from the Gi protein can also affect cellular responses through the activation of ion channels and downstream kinases. The effector mediating the response to the alpha subunit of Gq is phospholipase C (PLC) while that for the alpha subunit of G12/13 is a RhoA exchange factor. G-protein signalling can also be regulated by regulator of G-protein signalling proteins,18,19 expression of which can be affected via S1P receptor activation.20 Thus, coupling to particular G-proteins and downstream effectors dictates the nature of the cellular response and provides a level of selectivity to S1P signalling.

While selective G-protein coupling can explain the divergent signalling pathways associated with the members of the S1P receptor family, differential expression patterns for the receptor subtypes are also important determinants of cellular responses.6,21 The S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 receptors are widely expressed, whereas expression of S1P4 and S1P5 receptors is limited to the immune and nervous system.6,16,22 Furthermore, while S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 receptors are all present in the cardiovascular system,23–28 the predominant receptor subtypes in specific cardiac cell types differ, as described below.

In addition to S1P receptors, the myocardium has been shown to express both isozymes of sphingosine kinase, the enzyme that produces S1P.29,30 This enzyme is particularly enriched in cardiac fibroblasts. Furthermore, the myocardium is known to express S1P phosphatase, an enzyme that degrades S1P.31–33 Finally, circulating S1P is present at a high level in the blood within platelets and erythrocytes or bound to albumin and HDL.34 As circulating S1P is present in abundant quantities, particularly under pathophysiological conditions, the tissue distribution, cellular localization, and subtype selective coupling of S1P receptors to G-proteins would be expected to determine which signalling pathways are activated.

The effects of S1P receptor activation on the different cell types present in the cardiovascular system (myocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells) have been characterized to varying extents. S1P receptors on cardiomyocytes were initially studied for their effect on ion channels and contractility, but are now known to also be involved in hypertrophy and cardioprotection. Activation of S1P receptors on fibroblasts can mediate migration and proliferation, responses that are necessary for fibrosis and critical to cardiac remodelling. Finally, S1P can modulate vascular permeability, angiogenesis, and vascular tone by activating certain S1P receptor subtypes. While many reviews have been written about S1P receptor signalling, the purpose of this review is to discuss S1P receptor-mediated signalling in the various cell types within the cardiovascular system. We will focus on S1P signalling in cardiomyocytes, but will also provide comparative relevant information on the roles of S1P receptors in cardiac fibroblasts and the vasculature. More in-depth analysis of the role of S1P in the vasculature will be provided by other contributors to this spotlight issue.

2. Role of S1P receptors on cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes express S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 receptors. Quantitative PCR has shown the S1P1 receptor to be the predominant S1P receptor subtype on cardiomyocytes, with S1P2 and S1P3 receptor mRNA present at much lower levels23,24 (Table 1). Activation of cardiac S1P receptors has been reported to affect cardiac contractility and heart rate, induce hypertrophy, provide protection from ischaemia, and mobilize intracellular calcium. Determining which S1P receptor subtypes mediate specific responses has been difficult due to ubiquitous S1P receptor expression and a paucity of commercially available subtype-specific agonists/antagonists. We will, however, call attention to responses that can be specifically assigned to particular S1P receptor subtype(s) whenever possible.

Table 1.

Relative expression of S1P receptor subtypes in various cell types

| Tissue | Relative S1P receptor expression |

|---|---|

| Cardiac myocytes | S1P1 >> S1P3 > S1P2 |

| Cardiac fibroblasts | S1P3 >> S1P1 > S1P2 |

| Aortic smooth muscle cells | S1P2 > S1P3 >> S1P1 |

| Vascular endothelial cells | S1P1 > S1P3 >> S1P2 |

Comparison of S1P receptor subtype expression in various cell types found in the heart. Data for myocytes and fibroblasts are derived from studies of cells isolated from heart; those for vascular endothelium and smooth muscle are based on information from non-cardiac sources. >>, much greater than; >, greater than;=, similar.

2.1. S1P and cardioprotection

S1P has been demonstrated to protect the heart, as well as isolated myocytes, from a variety of insults both in vivo and ex vivo. In an early study, exogenous S1P as well as the related lysophospholipid, LPA, were shown to protect neonatal rat ventricular myocytes from hypoxia.35 In addition S1P generated intracellularly, via ganglioside GM-1 mediated activation of sphingosine kinase, appeared to protect myocytes from hypoxia to a similar extent as exogenously applied S1P.35 More recent experiments have shown that S1P also protects adult mouse ventricular myocytes from hypoxia.23 In order to determine which receptors mediate the observed cardioprotection, Karliner's laboratory developed an antibody that functions as an agonist only at S1P1 receptors.36 Subsequent studies showed that this S1P1 receptor agonist antibody protected myocytes from hypoxia to the same extent as exogenously applied S1P. Furthermore, studies using pharmacological inhibitors indicated that this protection occurred through either S1P1 or S1P3 receptors, was mediated by a PI3 kinase pathway, and likely involved activation of Akt and inactivation of GSK-3β.23 Additional studies showed that pertussis toxin and the S1P1/3 antagonist/S1P4 agonist, VPC23019, could block GM-1 mediated cardioprotection against hypoxia and glucose deprivation, suggesting that intracellularly produced S1P is exported from the cell and acts on cardiomyocyte S1P1 and S1P3 receptors coupled to Gi in an autocrine or paracrine manner. The additional finding that GM-1 is unable to reproduce this protective effect in sphingosine kinase knockout cardiomyocytes further substantiates that the effects of GM-1 are relatively specific for sphingosine kinase and lend support to the concept that intracellular S1P is exported from the cell and acts via cell surface S1P receptors.37

In the intact heart, S1P has also been shown to protect against global ischaemia reperfusion (I/R). Both exogenous S1P as well as intracellularly generated S1P (produced via GM-1 stimulation of sphingosine kinase) have been reported to improve recovery of cardiac function as measured by LVDP or creatine kinase release.38–40 Whereas the protection afforded by exogenous S1P administration was demonstrated to occur through a PKCε independent pathway (based on studies with PKCε knockout mice), protection afforded by intracellularly generated S1P required PKCε.40 Furthermore, deletion of the sphingosine kinase 1 gene and the subsequent decrease in the ability to produce endogenous S1P could be rescued by exogenous S1P treatment.41 The role of PKCε in mediating cardioprotection is unclear although it is noteworthy that while S1P does not cause translocation of PKCε, GM-1 stimulation results in PKC translocation and this may be a necessary step in GM-1 mediated sphingosine kinase activation. Further work from the Karliner laboratory suggests that it is the S1P1 receptor that mediates cardioprotection from global I/R. On the other hand, perfusion of the S1P1 receptor agonist, SEW2871, did not protect adult rat hearts from global I/R to the same extent as S1P, indicating that additional S1P receptor subtypes are involved in the cardioprotective response.42

Notably, several studies have examined the cardioprotective effects of S1P on the heart in vivo. Administration of exogenous S1P was shown by Levkau's group to protect the heart against damage from 30 min ischaemia/24 h reperfusion and a comparable effect was seen following administration of HDL, a known carrier of S1P.43–45 The protective effects of HDL and S1P were abolished when this response was examined in hearts from S1P3 receptor knockout mice46 and interestingly, inhibition of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) completely abolished HDL- or S1P-mediated cardioprotection, implicating NOS as an important mediator in this pathway.46 Studies from our laboratory utilized S1P2, S1P3, and S1P2,3 receptor double knockout mice and showed a significant increase in infarct size after 30 min ischaemia/2 h reperfusion when both S1P2 and S1P3 receptors were deleted.47 These data implicate endogenously supplied S1P in cardioprotection through effects on S1P2,3 receptors. A significant reduction in in vivo Akt phosphorylation was also observed in S1P2,3 receptor double knockout hearts following I/R, suggesting that S1P acting on S1P2 and S1P3 receptors mediates cardioprotection via Akt.47 The aforementioned findings on NOS and Akt as in vivo mediators of cardioprotection may be related since the loss of Akt activation in the S1P2,3 receptor double knockout mice could result in a decrease in eNOS activation; eNOS is a known substrate of Akt which has itself been shown to protect against cardiac damage from I/R injury48–50 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

S1P receptor-mediated signalling in the heart. Activation of the S1P1 receptor induces negative inotropy through effects of Gαi to decrease cAMP concentration and effects of Gβγ on ion channels. The S1P2 receptor is the primary receptor for mediating Rho activation and this receptor mediated pathway may participate in cardioprotection. The S1P3 receptor is the primary receptor coupling to PLC and the activation of this receptor also results in bradycardia. While the S1P2 and S1P3 receptors appear to collaborate in providing cardioprotection from ischaemia reperfusion injury in vivo, the S1P1 receptor has been suggested to be cardioprotective in the isolated cardiomyocytes.

Recent unpublished studies from the Levkau group have yielded the first data on the cardiac-specific S1P1 receptor knockout mouse (B. Levkau, personal communication). Generation of this alpha-MHC-Cre driven knockout line was necessary as the conventional S1P1 receptor knockout mouse shows embryonic lethality.51 Initial findings indicate that the S1P1 receptor knockout mouse displays a progressive heart failure phenotype, consistent with a basal protective effect of S1P. Interestingly, when subjected to 30 min ischaemia/24 h reperfusion, the S1P1 receptor knockout heart showed the same amount of IR-induced damage as the WT heart, suggesting that the S1P1 receptor in cardiomyocytes may not contribute to cardioprotection from in vivo I/R. This finding is compatible with our published evidence that the S1P2 and S1P3 receptors mediate cardioprotection,47 but contrasts with studies from the Karliner group indicating that the S1P1 receptor mediates cardioprotection.23 It is important to note that the protective effect of S1P1 against hypoxia was demonstrated in isolated myocytes and against global I/R, while our data and the recent finding from the Levkau group examined in vivo I/R. Additional studies will be needed to further investigate the cardioprotective mechanisms downstream of each S1P receptor subtype.

2.2. S1P and hypertrophy

There is evidence that another lysophospholipid, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), induces hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes via activation of Gi -and RhoA-mediated signalling pathways downstream of a family of GPCR's that are related yet distinct from S1P receptors.52,53 There is conflicting data, however, regarding the role of S1P in hypertrophy. An early study in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes concluded that S1P did not induce hypertrophy, as assessed by atrial natriuretic factor expression and phenylalanine incorporation, although the related sphingolipid, sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPC), was able to induce hypertrophy through an ERK1/2 dependent pathway.54 However, the mechanism of this remains unclear as SPC does not act as an agonist at any of the S1P receptor subtypes. Subsequent data from a different group demonstrated that S1P induces hypertrophy in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes as measured by cell size, phenylanine incorporation, cytoskeletal organization, and expression of brain natriuretic peptide.55 Importantly, this hypertrophic response appeared to be mediated by the S1P1 receptor as an anti-S1P1 receptor antibody blocked the S1P-mediated hypertrophy. In addition, inhibitor studies revealed that the S1P-mediated hypertrophy involved Gi coupled signalling pathways and activation of MAP kinases, Akt, p70 S6 kinase, and Rho.55 It should be recognized, however, that the Gi- and RhoA-mediated hypertrophy induced by LPA and S1P occurs more slowly and is less robust than the more canonical hypertrophic responses elicited through the activation of Gq/PLC signalling by norepinephrine, phenylyephrine, and endothelin.56

No studies have yet been conducted to determine whether S1P acts as a hypertrophic mediator in vivo. We have determined that S1P3 receptor knockout myocytes show a complete loss of S1P-mediated PLC activity, while this response is intact in S1P2 receptor knockout myocytes. This result is in agreement with that obtained using S1P receptor knockout mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells, which demonstrated that S1P3 receptor deletion prevented PLC activation.57 In light of the established relationship between Gq signalling and pressure overload induced hypertrophy in vivo, 58,59 it is intriguing to postulate that S1P3 receptor/Gq activation may contribute to the cardiac hypertrophic response in vivo. On the other hand, preliminary studies from our group indicate that S1P3 receptor knockout mice do not show diminished hypertrophy after transverse aortic constriction (TAC). These data suggest that S1P is not the predominant GPCR agonist responsible for Gq-mediated hypertrophy following TAC.

2.3. S1P in cardiac physiology

S1P is a known mediator of cardiac electrophysiological and contractile responses. Until recently, the mechanisms and receptor subtypes mediating these functions have remained elusive. The first in vivo studies demonstrated that S1P treatment of rat or canine hearts resulted in positive chronotropy and vasoconstriction while decreasing inotropy and coronary blood flow. As these responses were not blocked by adrenergic antagonists and S1P did not affect adenylyl cyclase activity, this suggested involvement of a novel signalling pathway which was subsequently explained by discovery of S1P receptors.60,61 It should also be noted that this in vivo negative inotropic response could be explained in part by diminished coronary blood flow.60,61 However, in vitro studies showed that S1P, like acetylcholine, stimulates a receptor-activated inward rectifier K+ current (IK.Ach), which is known to contribute to resting membrane potential and the shape of action potentials in guinea pig,62–64 rabbit,65 human, and mouse atrial myocytes.66 The effects of S1P on IK.Ach were attributed to activation of the S1P3 receptor as suramin, a putative S1P3 receptor antagonist, blocked these effects. This conclusion must be tempered by the knowledge that while suramin can act as an S1P3 receptor antagonist,67 it also has a myriad of non-specific pharmacological properties.68 The S1P3 receptor has also been implicated in regulating heart rate and several studies have shown that stimulation of this receptor results in bradycardia in both mice and humans.69–71 This adverse effect of S1P3 receptor activation, apparently mediated at the level of the SA node, has serious therapeutic implications. Concern about S1P-mediated bradycardia arises because several non-specific S1P receptor agonists (e.g. FTY720) which inhibit lymphocyte egress and reduce the number of circulating lymphocytes are being investigated as potential immunosuppressive agents for transplant procedures or in multiple sclerosis.72,73

In more recent studies in which mouse ventricular myocytes were used to examine S1P-mediated changes in contractility, S1P treatment dramatically decreased cell shortening and was able to antagonize isoproterenol-induced increases in cAMP and positive inotropy.24,74 The S1P1 receptor specific agonist, SEW2871, was as efficacious as S1P at antagonizing isoproterenol-induced contractility, and the S1P1,3 receptor antagonist/S1P4 agonist, VPC23019, blocked the negative inotropic effects of SEW2871 which was observed in cells lacking S1P3 receptors.74 Taken together, these results suggest that the S1P1 receptor is the predominant receptor mediating the negative inotropic effects of S1P in mouse ventricular myocytes; although the S1P3 receptor may also play a minor role. The S1P4 receptor is not expressed in cardiac myocytes. These results are corroborated by the unpublished findings from the Levkau group indicating that the ability of S1P to inhibit isoproterenol-stimulated contractility is abolished in the cardiac specific S1P1 receptor knockout myocytes (B. Levkau, personal communication). S1P-mediated negative inotropy was also shown to be significantly, but not completely, blocked by the IK.Ach inhibitor tertiapin, further substantiating the involvement of IK.Ach, a Gi (βγ) regulated ion channel, in S1P1-mediated contractile changes. Thus, S1P1 receptor-mediated negative inotropy may result from both the ability of the alpha subunit of Gi to inhibit cyclic AMP formation (thus PKA-mediated L-type Ca2+ channel activation), and the ability of βγ subunits of Gi to act on IK.Ach74 (Figure 1).

Remarkably, selective coupling of the S1P1 receptor in mediating negative inotropy in ventricular myocytes may be explained by its subcellular localization. The S1P1 receptor has been localized to caveolae in COS cells75 and more recently in adult mouse ventricular myocytes.24 Caveolae are known to be enriched in numerous signalling components.76–78 Our studies examined the ability of S1P to decrease isoproterenol-induced cAMP production and positive inotropy in mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes and found these effects to be completely inhibited by treatment with the caveolar disrupting agent methyl-β-cyclodextrin.24 Thus, it is likely that as a result of its localization near components of the cAMP signalling pathway, the S1P1 receptor is uniquely able to antagonize isoproterenol-stimulated cAMP production and positive intropy, whereas other S1P receptor subtypes capable of coupling to Gi do not induce this same response.24

3. Role of S1P receptors in vascular function

Endothelial cells are found lining the blood vessels of the heart and are involved in a number of important processes including regulation of barrier integrity and angiogenesis. S1P regulates these processes and also stimulates the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells.79–82 Aberrant vascular maturation, apparently resulting from the inability of S1P to activate the GTPase Rac, is observed in global S1P1 receptor knockout mice and may be responsible for the impaired development and embryonic lethality that occurs between E12.5 and E14.5.51,83 The finding that the endothelial specific knockout of the S1P1 receptor phenocopies the embryonic lethality seen in the global knockout demonstrates that S1P1 receptors on endothelial cells play a critical role in this aspect of vascular development.83

Endothelial cells express S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 receptors, the S1P1 receptor being the most abundant subtype, with the others expressed at much lower levels84–87 (Table 1). Most S1P-mediated responses on endothelial cells occur via the S1P1 receptor alone or in combination with the S1P3 receptor. S1P-mediated migration, angiogenesis, and adherens junction formation all require both the Gi mediated activity of the S1P1 receptor and the Gq/G12,13 mediated activity of the S1P3 receptor.85,86,88 The requirement for the S1P3 receptor has been further confirmed in studies demonstrating that a peptide derived from the second intracellular loop of the S1P3 receptor can induce pro-angiogenic responses.89 S1P also promotes endothelial cell integrity, stabilizes newly formed vessels, and antagonizes the disruptive effects of thrombin on barrier integrity through its effects on S1P1 and S1P3 receptors.90–92

The expression pattern for S1P receptors on smooth muscle cells differs from that of endothelial cells (Table 1). Smooth muscle cells express S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 receptors, but levels of the S1P1 receptor are significantly reduced in adulthood such that the S1P2 and S1P3 receptors become the predominant receptor subtypes.26,93 These distinct receptor expression profiles may explain why smooth muscle cells respond to S1P differently than endothelial cells. Stimulation of either S1P1 or S1P3 receptors leads to activation of Rac, whereas S1P2 receptor stimulation inhibits Rac activation. Interestingly, the mechanism by which the activation of S1P2 receptors inhibits Rac activation is in part through activation of a Rho/Rho kinase pathway.94 In concordance with this role for SIP2 receptors, our group showed that S1P-mediated Rho activation is nearly abolished in MEF cells isolated from S1P2 receptor knockout mice and suggested that Rho activation is most effectively coupled to the S1P2 receptor.95 Due to the greater relative abundance of S1P2 receptors in smooth muscle and S1P1 receptors in endothelial cells, S1P actually inhibits migration of smooth muscle cells, whereas it promotes migration of endothelial cells.26

The ability of S1P to activate Rho in smooth muscle cells promotes myosin light chain phosphorylation which in turn contributes to vasoconstriction.96,97 Recent studies have exploited S1P receptor knockout mice to determine the involvement of individual S1P receptor subtypes in regulating vascular tone. S1P failed to increase vascular tone in basilar arteries isolated from S1P3 receptor knockout mice, while arteries from WT and S1P2 receptor knockout mice showed the expected vasoconstrictor response to S1P treatment.98 The S1P3 receptor thus appears to be the primary mediator of S1P-induced vasoconstriction, although other studies suggest a role for the S1P2 receptor in regulating resting vascular tone and myogenic responses. S1P can promote the formation of nitric oxide (NO) in endothelial cells and release of NO relaxes smooth muscle cells.99,100 Whether responses downstream of the S1P2 receptor are mediated solely via smooth muscle cells or also by changes in endothelial function is not yet clear.101

4. Role of S1P receptors in cardiac fibroblasts

While myocytes compose the bulk of the ventricular mass, fibroblasts are the most abundant cell type in the heart and function to organize the cardiac myocytes and preserve the ability of cardiac myocytes to respond to many stimuli. Cardiac fibroblasts express predominantly S1P3 receptors with much lower levels of S1P1 and S1P2 receptors as assessed by quantitative PCR.74 In addition, cardiac fibroblasts have elevated levels of sphingosine kinase activity when compared with cardiomyocytes and thus appear to be an important source of endogenous S1P in the heart.102 A recent study demonstrates that S1P induces proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts as measured by increased DNA synthesis and alpha-smooth muscle actin expression.103 How S1P regulates proliferation and transformation of cardiac fibroblasts is unclear, although it appears to involve activation of MAP kinases and of Rho downstream of the S1P2 receptor. S1P also causes proliferation and differentiation in a number of non-cardiac fibroblasts.104–106 For example, hepatic fibrosis induced by liver injury is diminished in S1P2 receptor knockout mice. Correspondingly, an increase in S1P production by the sphingosine kinase activator, K6PC-5, results in increased fibroblast proliferation and collagen production in the mouse dermis.107,108

Conclusions

The heart is a complex organ in which numerous cell types respond to S1P in different manners. Early studies focusing on individual cell types have led to more complex in vivo studies to elucidate the physiological consequences of S1P signalling in the cardiovascular system. This has proven challenging as S1P receptor pharmacology is still in its infancy, but has increasingly been aided by the availability of subtype-specific S1P receptor knockout mice. There is now broad consensus that S1P plays a critical role in maintaining cardiac cell survival and function. Further analysis of the actions of each S1P receptor subtype on the constituent cell types within the heart will be necessary for the rational design of potential therapeutics targeting S1P signalling in the desired cell compartment and at the appropriate time.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant HL28143.

References

- 1.Zhang H, Desai NN, Olivera A, Seki T, Brooker G, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a novel lipid, involved in cellular proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:155–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh TK, Bian J, Gill DL. Intracellular calcium release mediated by sphingosine derivatives generated in cells. Science. 1990;248:1653–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.2163543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne SG, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: dual messenger functions. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:54–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olivera A, Rosenfeldt HM, Bektas M, Wang F, Ishii I, Chun J, et al. Sphingosine kinase type 1 Induces G12/13-mediated stress fiber formation yet promotes growth and survival independent of G protein coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46452–46460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun J, Goetzl EJ, Hla T, Igarashi Y, Lynch KR, Moolenaar W, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXIV. Lysophospholipid Receptor Nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:265–269. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii I, Fukushima N, Ye X, Chun J. Lysophospholipid receptors: signaling and biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:321–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiegel S, Milstien S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:397–407. doi: 10.1038/nrm1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MJ, Evans M, Hla T. The inducible G protein-coupled receptor edg-1 signals via the G(i)/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11272–11279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MJ, Van Brocklyn JR, Thangada S, Liu CH, Hand AR, Menzeleev R, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate as a ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor EDG-1. Science. 1998;279:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zondag GC, Postma FR, Etten IV, Verlaan I, Moolenaar WH. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling through the G-protein-coupled receptor Edg-1. Biochem J. 1998;330:605–609. doi: 10.1042/bj3300605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windh RT, Lee M-J, Hla T, An S, Barr AJ, Manning DR. Differential coupling of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors Edg-1, Edg-3, and h218/Edg-5 to the Gi, Gq, and G12 families of heterotrimeric G proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27351–27358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kon J, Sato K, Watanabe T, Tomura H, Kuwabara A, Kimura T, et al. Comparison of intrinsic activities of the putative sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor subtypes to regulate several signaling pathways in their cDNA-transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23940–23947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto H, Takuwa N, Yatomi Y, Gonda K, Shigematsu H, Takuwa Y. EDG3 is a functional receptor specific for sphingosine 1-phosphate and sphingosylphosphorylcholine with signaling characteristics distinct from EDG1 and AGR16. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:203–208. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van B, Jr, Graler MH, Bernhardt G, Hobson JP, Lipp M, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor EDG-6. Blood. 2000;95:2624–2629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamazaki Y, Kon J, Sato K, Tomura H, Sato M, Yoneya T, et al. Edg-6 as a putative sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor coupling to Ca(2+) signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:583–589. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Im DS, Heise CE, Ancellin N, O’Dowd BF, Shei GJ, Heavens RP, et al. Characterization of a novel sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor, Edg-8. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14281–14286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malek RL, Toman RE, Edsall LC, Wong S, Chiu J, Letterle CA, et al. Nrg-1 belongs to the endothelial differentiation gene family of G protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5692–5699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollinger S, Hepler JR. Cellular regulation of RGS proteins: modulators and integrators of G protein signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:527–559. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wieland T, Lutz S, Chidiac P. Regulators of G protein signalling: a spotlight on emerging functions in the cardiovascular system. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuebe S, Wieland T, Kraemer E, Stritzky A, Schroeder D, Seekamp S, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and endothelin-1 induce the expression of rgs16 protein in cardiac myocytes by transcriptional activation of the rgs16 gene. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;376:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anliker B, Chun J. Lysophospholipid G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20555–20558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graler MH, Grosse R, Kusch A, Kremmer E, Gudermann T, Lipp M. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1P4 regulates cell shape and motility via coupling to Gi and G12/13. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:507–519. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Honbo N, Goetzl EJ, Chatterjee K, Karliner JS, Gray MO. Signals from type 1 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors enhance adult mouse cardiac myocyte survival during hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3150–H3158. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00587.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Means CK, Miyamoto S, Chun J, Brown JH. S1P1 receptor localization confers selectivity for Gi-mediated cAMP and contractile responses. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11954–11963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707422200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazurais D, Robert P, Gout B, Berrebi-Bertrand I, Laville MP, Calmels T. Cell type-specific localization of human cardiac S1P receptors. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:661–670. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alewijnse AE, Peters SL, Michel MC. Cardiovascular effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate and other sphingomyelin metabolites. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:666–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chae SS, Proia RL, Hla T. Constitutive expression of the S1P1 receptor in adult tissues. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2004;73:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liliom K, Sun G, Bunemann M, Virag T, Nusser N, Baker DL, et al. Sphingosylphosphocholine is a naturally occurring lipid mediator in blood plasma: a possible role in regulating cardiac function via sphingolipid receptors. Biochem J. 2001;355:189–197. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohama T, Olivera A, Edsall L, Nagiec MM, Dickson R, Spiegel S. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of murine sphingosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23722–23728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Sugiura M, Nava VE, Edsall LC, Kono K, Poulton S, et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel mammalian sphingosine kinase type 2 isoform. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19513–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukuda Y, Kihara A, Igarashi Y. Distribution of sphingosine kinase activity in mouse tissues: contribution of SPHK1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeda M, Kihara A, Igarashi Y. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase SPL is an endoplasmic reticulum-resident, integral membrane protein with the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate binding domain exposed to the cytosol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wendler CC, Rivkees SA. Sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibits cell migration and endothelial to mesenchymal cell transformation during cardiac development. Dev Biol. 2006;291:264–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yatomi Y, Igarashi Y, Yang L, Hisano N, Qi R, Asazuma N, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate, a bioactive sphingolipid abundantly stored in platelets, is a normal constituent of human plasma and serum. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1997;121:969–973. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karliner JS, Honbo N, Summers K, Gray MO, Goetzl EJ. The lysophospholipids sphingosine-1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid enhance survival during hypoxia in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1713–1717. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graeler MH, Kong Y, Karliner JS, Goetzl EJ. Protein kinase C epsilon dependence of the recovery from down-regulation of S1P1 G protein-coupled receptors of T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27737–27741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tao R, Zhang J, Vessey DA, Honbo N, Karliner JS. Deletion of the sphingosine kinase-1 gene influences cell fate during hypoxia and glucose deprivation in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vessey DA, Li L, Kelley M, Karliner JS. Combined sphingosine, S1P and ischemic postconditioning rescue the heart after protracted ischemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lecour S, Smith RM, Woodward B, Opie LH, Rochette L, Sack MN. Identification of a novel role for sphingolipid signaling in TNF alpha and ischemic preconditioning mediated cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:509–518. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin ZQ, Zhou HZ, Zhu P, Honbo N, Mochly-Rosen D, Messing RO, et al. Cardioprotection mediated by sphingosine-1-phosphate and ganglioside GM-1 in wild-type and PKC epsilon knockout mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1970–H1977. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin ZQ, Zhang J, Huang Y, Hoover HE, Vessey DA, Karliner JS. A sphingosine kinase 1 mutation sensitizes the myocardium to ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukada YT, Sanna MG, Rosen H, Gottlieb RA. S1P1-selective agonist SEW2871 exacerbates reperfusion arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:660–669. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318157a5fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keul P, Sattler K, Levkau B. HDL and its sphingosine-1-phosphate content in cardioprotection. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12:301–306. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levkau B, Hermann S, Theilmeier G, van der Giet M, Chun J, Schober O, et al. High-density lipoprotein stimulates myocardial perfusion in vivo. Circulation. 2004;110:3355–3359. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147827.43912.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nofer JR, van der Giet M, Tolle M, Wolinska I, von Wnuck LK, Baba HA, et al. HDL induces NO-dependent vasorelaxation via the lysophospholipid receptor S1P3. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:569–581. doi: 10.1172/JCI18004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theilmeier G, Schmidt C, Herrmann J, Keul P, Schafers M, Herrgott I, et al. High-density lipoproteins and their constituent, sphingosine-1-phosphate, directly protect the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo via the S1P3 lysophospholipid receptor. Circ. 2006;114:1403–1409. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Means CK, Xiao CY, Li Z, Zhang T, Omens JH, Ishii I, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate S1P2 and S1P3 receptor-mediated Akt activation protects against in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2944–H2951. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01331.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones SP, Greer JJ, van Haperen R, Duncker DJ, de Crom R, Lefer DJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates congestive heart failure in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4891–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0837428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones SP, Girod WG, Palazzo AJ, Granger DN, Grisham MB, Jourd’Heuil D, et al. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury is exacerbated in absence of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1567–H1573. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones S, Greer JJ, Kakkar AK, Ware PD, Turnage RH, Hicks M, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H276–H282. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita H, Mi Y, Deng C-X, Hobson JP, et al. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:951–961. doi: 10.1172/JCI10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilal-Dandan R, Means CK, Gustafsson AB, Morissette MR, Adams JW, Brunton LL, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid induces hypertrophy of neonatal cardiac myocytes via activation of Gi and Rho. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:481–493. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goetzl EJ, Lee H, Azuma T, Stossel TP, Turck CW, Karliner JS. Gelsolin binding and cellular presentation of lysophosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14573–14578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sekiguchi K, Yokoyama T, Kurabayashi M, Okajima F, Nagai R. Sphingosylphosphorylcholine induces a hypertrophic growth response through the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade in rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1999;85:1000–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robert P, Tsui P, Laville MP, Livi GP, Sarau HM, Bril A, et al. Edg1 receptor stimulation leads to cardiac hypertrophy in rat neonatal myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1589–1606. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei L. Lysophospholipid signaling in cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:465–468. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishii I, Friedman B, Ye X, Kawamura S, McGiffert C, Contos JJ, et al. Selective loss of sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling with no obvious phenotypic abnormality in mice lacking its G protein-coupled receptor, LP(B3)/EDG-3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33697–33704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dorn GW, Tepe NM, Lorenz JW, Koch WJ, Liggett SB. Low- and high-level transgenic expression of β2-adrenergic receptors differentially affect cardiac hypertrophy and function in Gαq-overexpressing mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6400–6405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wettschureck N, Rutten H, Zywietz A, Gehring D, Wilkie TM, Chen J, et al. Absence of pressure overload induced myocardial hypertrophy after conditional inactivation of Galphaq/Galpha11 in cardiomyocytes. Nat Med. 2001;7:1236–1240. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sugiyama A, Aye NN, Yatomi Y, Ozaki Y, Hashimoto K. Effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate, a naturally occurring biologically active lysophospholipid, on the rat cardiovascular system. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2000;82:338–342. doi: 10.1254/jjp.82.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sugiyama A, Yatomi Y, Ozaki Y, Hashimoto K. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces sinus tachycardia and coronary vasoconstriction in the canine heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bunemann M, Brandts B, zu Heringdorf DM, van Koppen CJ, Jakobs KH, Pott L. Activation of muscarinic K+ current in guinea-pig atrial myocytes by sphingosine-1-phosphate. J Physiol. 1995;489:701–777. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bunemann M, Liliom K, Brandts BK, Pott L, Tseng JL, Desiderio DM, et al. A novel membrane receptor with high affinity for lysosphingomyelin and sphingosine 1-phosphate in atrial myocytes. EMBO J. 1996;15:5527–5534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ochi R, Momose Y, Oyama K, Giles WR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate effects on guinea pig atrial myocytes: alterations in action potentials and K+ currents. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo J, MacDonell KL, Giles WR. Effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate on pacemaker activity in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. Pflugers Arch. 1999;438:642–648. doi: 10.1007/s004249900067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Himmel HM, Meyer zu HD, Graf E, Dobrev D, Kortner A, Schuler S, et al. Evidence for Edg-3 receptor-mediated activation of I(K.ACh) by sphingosine-1-phosphate in human atrial cardiomyocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:449–454. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ancellin N, Hla T. Differential pharmacological properties and signal transduction of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors EDG-1, EDG-3, and EDG-5. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18997–19002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Voogd TE, Vansterkenburg EL, Wilting J, Janssen LH. Recent research on the biological activity of suramin. Pharmacol Rev. 1993;45:177–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanna MG, Liao J, Jo E, Alfonso C, Ahn MY, Peterson MS, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor subtypes S1P1 and S1P3, respectively, regulate lymphocyte recirculation and heart rate. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13839–13848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Forrest M, Sun SY, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Card D, Doherty G, et al. Immune cell regulation and cardiovascular effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonists in rodents are mediated via distinct receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:758–768. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Budde K, Schmouder RL, Brunkhorst R, Nashan B, Lucker PW, Mayer T, et al. First human trial of FTY720, a novel immunomodulator, in stable renal transplant patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1073–1083. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1341073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Budde K, Schutz M, Glander P, Peters H, Waiser J, Liefeldt L, et al. FTY720 (fingolimod) in renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(Suppl. 17):17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martini S, Peters H, Bohler T, Budde K. Current perspectives on FTY720. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:505–518. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Landeen LK, Dederko DA, Kondo CS, Hu BS, Aroonsakool N, Haga JH, et al. Mechanisms of the negative inotropic effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate on adult mouse ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H736–H749. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00316.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Igarashi J, Michel T. Agonist-modulated targeting of the EDG-1 receptor to plasmalemmal caveolae. eNOS transactivation by sphingosine 1-phosphate and the role of caveolin-1 in sphingolipid signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32363–32370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shaul PW, Anderson RGW. Role of plasmalemmal caveolae in signal transduction. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L843–L851. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.5.L843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pike LJ. Lipid rafts: bringing order to chaos. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:655–667. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R200021-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ostrom RS, Insel PA. The evolving role of lipid rafts and caveolae in G protein-coupled receptor signaling: implications for molecular pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:235–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Osborne N, Stainier DY. Lipid receptors in cardiovascular development. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McVerry BJ, Garcia JG. Endothelial cell barrier regulation by sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:1075–1085. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kimura T, Watanabe T, Sato K, Kon J, Tomura H, Tamama K, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates proliferation and migration of human endothelial cells possibly through the lipid receptors, Edg-1 and Edg-3. Biochem J. 2000;348:71–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Osada M, Yatomi Y, Ohmori T, Ikeda H, Ozaki Y. Enhancement of sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced migration of vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells by an EDG-5 antagonist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299:483–487. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Allende ML, Yamashita T, Proia RL. G-protein-coupled receptor S1P1 acts within endothelial cells to regulate vascular maturation. Blood. 2003;102:3665–3667. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kluk MJ, Hla T. Signaling of sphingosine-1-phosphate via the S1P/EDG-family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang F, Van Brocklyn JR, Hobson JP, Movafagh S, Zukowska-Grojec Z, Milstien S, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates cell migration through a G(i)-coupled cell surface receptor. Potential involvement in angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35343–35350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee MJ, Thangada S, Claffey KP, Ancellin N, Liu CH, Kluk M, et al. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. 1999;99:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Michel MC, Mulders AC, Jongsma M, Alewijnse AE, Peters SL. Vascular effects of sphingolipids. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2007;96:44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ohmori T, Yatomi Y, Okamoto H, Miura Y, Rile G, Satoh K, et al. G(i)-mediated Cas tyrosine phosphorylation in vascular endothelial cells stimulated with sphingosine 1-phosphate: possible involvement in cell motility enhancement in cooperation with Rho-mediated pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5274–5280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Licht T, Tsirulnikov L, Reuveni H, Yarnitzky T, Ben-Sasson SA. Induction of pro-angiogenic signaling by a synthetic peptide derived from the second intracellular loop of S1P3 (EDG3) Blood. 2003;102:2099–2107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.English D, Brindley DN, Spiegel S, Garcia JG. Lipid mediators of angiogenesis and the signalling pathways they initiate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:228–239. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schaphorst KL, Chiang E, Jacobs KN, Zaiman A, Natarajan V, Wigley F, et al. Role of sphingosine-1 phosphate in the enhancement of endothelial barrier integrity by platelet-released products. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L258–L267. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00311.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garcia JG, Liu F, Verin AD, Birukova A, Dechert MA, Gerthoffer WT, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by Edg-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:689–701. doi: 10.1172/JCI12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kluk MJ, Hla T. Role of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor EDG-1 in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Circ Res. 2001;89:496–502. doi: 10.1161/hh1801.096338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sanchez T, Skoura A, Wu MT, Casserly B, Harrington EO, Hla T. Induction of vascular permeability by the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-2 (S1P2R) and its downstream effectors ROCK and PTEN. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1312–1318. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.143735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ishii I, Ye X, Friedman B, Kawamura S, Contos JJ, Kingsbury MA, et al. Marked perinatal lethality and cellular signaling deficits in mice null for the two sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptors, S1P2/LPB2/EDG-5 and S1P3/LPB3/EDG-3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25152–25159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Takuwa Y. Subtype-specific differential regulation of Rho family G proteins and cell migration by the Edg family sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:112–120. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ryu Y, Takuwa N, Sugimoto N, Sakurada S, Usui S, Okamoto H, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a platelet-derived lysophospholipid mediator, negatively regulates cellular Rac activity and cell migration in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2002;90:325–332. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Salomone S, Potts EM, Tyndall S, Ip PC, Chun J, Brinkmann V, et al. Analysis of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors involved in constriction of isolated cerebral arteries with receptor null mice and pharmacological tools. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:140–147. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mulders AC, Hendriks-Balk MC, Mathy MJ, Michel MC, Alewijnse AE, Peters SL. Sphingosine kinase-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2043–2048. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237569.95046.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Igarashi J, Michel T. S1P and eNOS regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lorenz JN, Arend LJ, Robitz R, Paul RJ, MacLennan AJ. Vascular dysfunction in S1P2 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor knockout mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R440–R446. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00085.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kacimi R, Vessey DA, Honbo N, Karliner JS. Adult cardiac fibroblasts null for sphingosine kinase-1 exhibit growth dysregulation and an enhanced proinflammatory response. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lowe NG, Swaney JS, Moreno KM, Sabbadini RA. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and sphingosine kinase are critical for TGF-β-stimulated collagen production by cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:303–312. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang F, Nobes CD, Hall A, Spiegel S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates Rho-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1997;324:481–488. doi: 10.1042/bj3240481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Olivera A, Kohama T, Edsall L, Nava V, Cuvillier O, Poulton S, et al. Sphingosine kinase expression increases intracellular sphingosine-1-phosphate and promotes cell growth and survival. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:545–548. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Urata Y, Nishimura Y, Hirase T, Yokoyama M. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in lung fibroblasts via Rho-kinase. Kobe J Med Sci. 2005;51:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Serriere-Lanneau V, Teixeira-Clerc F, Li L, Schippers M, de Wries W, Julien B, et al. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1P2 triggers hepatic wound healing. FASEB J. 2007;21:2005–2013. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6889com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Park HY, Youm JK, Kwon MJ, Park BD, Lee SH, Choi EH. K6PC-5, a novel sphingosine kinase activator, improves long-term ultraviolet light-exposed aged murine skin. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:829–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]