Abstract

Purpose: The primary aim of this study was to test the stress process model (SPM; Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990) in a racially diverse sample of Alzheimer's caregivers (CGs) using structural equation modeling (SEM) and regression techniques. A secondary aim was to examine race or ethnicity as a moderator of the relation between latent constructs (e.g., subjective stressors and role strain) in the SPM. Sample: Participants included White or Caucasian (n = 212), Black or African American (n = 201), and Hispanic or Latino (n = 196) Alzheimer's CGs from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH) II clinical trial. Results: SEM revealed that the Pearlin model obtains a satisfactory fit across race or ethnicity in the REACH II data, despite significant racial differences in each of the latent constructs. Race or ethnicity moderated the impact of resources on intrapsychic strain, such that CGs reported similar intrapsychic strain across race at lower levels of resources, but White or Caucasian CGs reported more intrapsychic strain than Black or African American or Hispanic or Latino CGs when resources are higher. Implications: Strengths and weaknesses for each race or ethnicity vary considerably, suggesting that interventions must target different aspects of the stress process to provide optimal benefit for individuals of different cultural or ethnic backgrounds.

Keywords: Race or ethnicity, Stress process, Caregiving, Alzheimer's disease

Caring for a loved one with Alzheimer's disease or a related disorder (ADRD) can have a devastating effect on the emotional and physical well-being of the primary caregiver (CG), as illustrated by the variety of stress process models (SPMs; e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990) developed to guide examination of the caregiving process. Many studies (e.g., Dilworth-Anderson, Goodwin, & Williams, 2004) have isolated portions of the Pearlin SPM (i.e., context variables, stressors) to predict important CG outcomes such as health, emotional well-being, and desire to institutionalize the care recipient (CR). Following the 2006 National Consensus Development Conference, the Family Caregiver Alliance (FCA) published a report suggesting that the Pearlin SPM was a particularly useful tool for both research and practice. The FCA consensus report makes Pearlin’s original SPM accessible to professionals who work with family CGs by suggesting measures to be used for each construct (FCA, 2006).

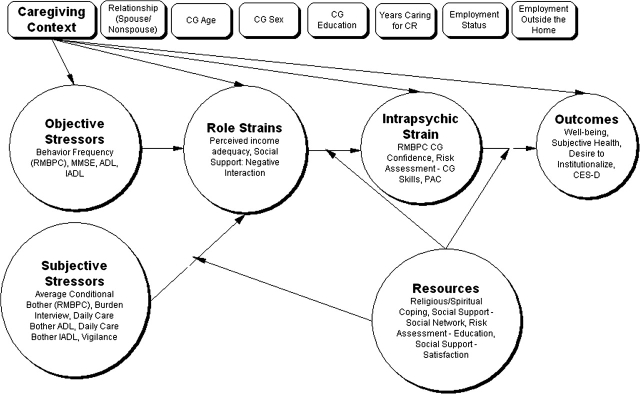

As shown in Figure 1, the SPM proposes that caregiving context variables affect each part of the stress process and can have implications for the types of stressors facing CGs, the perception or appraisal of those stressors, and outcomes such as CG depression and perceptions of physical health. Specifically, age, gender, employment status, and relationship to the CR affect CG outcomes within the SPM (FCA, 2006). One potentially important variable that is missing from the Pearlin SPM is the race or ethnicity of the CG. Racial or ethnic groups may vary in the perceived intensity of stressors, availability of resources, and use of coping strategies, as well as the relation of stressors, resources, and strategies to CG outcomes (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2005).

Figure 1.

Stress process model based on Pearlin and colleagues' (1990) original conceptualization.

Each circle includes one latent construct (in bold font) and its indicators. Indicators and latent construct are depicted inside the circles rather than in boxes outside the circles to enhance readability of the model.

In a meta-analysis of caregiving research for a period of 20 years, Dilworth-Anderson, Williams, and Gibson (2002) found significant racial or ethnic differences in the caregiving context. For example, Whites or Caucasians were more likely than Blacks or African Americans to utilize only immediate family in caregiving and received more social services. Furthermore, Black or African Americans had more members in their caregiving networks, were more likely to include friends and neighbors as resources, and were more likely to share caregiving responsibilities than were White or Caucasians. Black or African American CGs are also less likely to invoke formal supports than their White or Caucasian counterparts (Miller & Guo, 2000). Moreover, Lawton, Rajagopal, Brody, and Kleban (1992) found Black or African Americans to have higher levels of mastery, lower subjective burden, and greater satisfaction within the caregiving role. Haley and colleagues (1996) noted that Black or African American families are more likely than White or Caucasians to view caregiving as a natural part of the life course. Black or African Americans report lower anxiety, greater religious coping, and less use of psychotropic medications than White or Caucasians (Roff, Burgio, Gitlin, Nichols, & Chaplin, 2004). Many other risk factors for depression, including low self-efficacy, severity of patient impairment, dissatisfaction with social support, and higher appraisals of stress present differently in Black or African American and White or Caucasian CGs (Haley, Lamond, Han, Burton, & Schonwetter, 2003).

Hispanic or Latino CGs are distinctly different from White or Caucasians and Black or African Americans in ways that may be critical for a better understanding of the stress process. Hispanic or Latino CGs, particularly Mexican American CGs, are more likely to have to quit their jobs to provide care and more often share the caregiving role than other racial or ethnic groups (Aranda & Knight, 1997). Hispanic or Latino individuals are also at increased risk for diabetes and other illnesses that may produce more debilitating forms of dementia that affect individuals at a younger age than their White or Caucasian or Black or African American counterparts. Moreover, Aranda and Knight reported that Hispanic or Latino individuals access long-term care services at lower rates. Language barriers may increase risk of isolation and lead to reduced access to educational materials regarding protective factors, services, and treatment of illnesses such as diabetes and other risk factors. Despite being exposed to more stressors than White or Caucasian CGs and reporting more hours of care, Hispanic or Latino CGs utilize more religious coping and appear to be more resilient in the face of stress through positive appraisal (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2005).

Although differences between Black or African Americans and Hispanic or Latinos are numerous, some shared challenges of these ethnic or racial groups merit further exploration. Pinquart and Sörensen (2005) concluded that the literature on informal support and race or ethnicity is mixed. They suggest this might be a result of a cohort effect, with younger generations having less social support than their predecessors. Furthermore, Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino CGs are more likely to be employed in jobs with reduced scheduling flexibility. They are also more likely to be raising children concurrently with their elder caregiving duties. Notably, these CGs are less likely to be spousal CGs than White or Caucasians and are therefore typically younger in age (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2005). At each level of the stress process, divergent patterns emerge in the existing caregiving literature across races in appraisal, moderating factors, and psychological distress. Yet, these differences have not been jointly examined in a single study utilizing a racially or ethnically diverse group of CGs. Integrating existing knowledge of racial differences into the widely used Pearlin SPM will become increasingly important as racial diversity in the United States continues to increase.

This study addresses two aims. First, it tests the SPM in its entirety through secondary analysis of the baseline assessment data from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH) II project. Although numerous studies have isolated components of the Pearlin model or tested modified versions, the current study is the first, to our knowledge, to test the entire model without altering its original structure. To test this aim, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the fit of the SPM measurement model and generate values of the latent constructs. Following this, we used regression techniques to examine the relations among the constructs because it is better suited to examine moderating effects, which are central to the stress process (e.g., the impact of resources at several points in the model). The REACH interventions and assessments were designed within a stress–health framework (Schulz, Gallagher-Thompson, Haley, & Czaja, 2000), making them well suited to test the SPM. Second, we tested the model with race or ethnicity as a moderator to determine whether the proposed relations among latent constructs varied by race or ethnicity.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

We examined secondary data drawn from the baseline assessment for the REACH II (2004–2006; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00177489) project supported through the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research. Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health II was a unique multisite clinical trial that implemented and evaluated a multicomponent psychosocial intervention across five sites for 6 months. Data for 642 CG/CR dyads were collected in the randomized clinical trial at Birmingham, Memphis, Miami, Palo Alto, and Philadelphia.

Of the 642 CGs included in the study, 33 were excluded due to missing baseline data. The remaining 609 participants were White or Caucasian, n = 212 (34.8%); Black or African American, n = 201 (33%); and Hispanic or Latino, n = 196 (32.2%). Although there are significant differences in age, F(2, 606) = 55.011, p < .001; education, F(2, 606) = 12.137, p < .001; and years providing care, F(2, 606) = 3.826, p = .022, among racial or ethnic groups, individuals who were excluded from the analyses due to missing data did not differ significantly from those included in the analyses.

Participants were recruited from multiple community organizations, with special attention paid to the recruitment of minority CGs. Caregivers were included if they were at least 21 years old, living with or sharing cooking facilities with the CR, providing an average of 4 or more hours of care per day to a CR with at least two functional impairments of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) or one activity of daily living (ADL) impairment (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963; Lawton & Brody, 1969), providing care for at least the last 6 months, and reporting at least two symptoms of distress associated with caregiving (Belle et al., 2006). The CR had to have a diagnosis of ADRD or a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of 23 or lower; however, bed-bound CRs with a score of zero on the MMSE were excluded.

After obtaining informed consent from eligible participants, baseline data were collected during a face-to-face interview. Detailed information about the overall REACH II study, psychometric properties of all measures, recruitment procedures, and intervention outcomes are described elsewhere (Belle et al., 2006).

Measures

Indicators used to define the latent constructs of the SPM are described subsequently. Our conceptualization and testing of the SPM were guided by Pearlin and colleagues (Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 1995; Pearlin et al., 1990) and the FCA’s consensus report (FCA, 2006).

Caregiving Context Variables

Observed values for the caregiving context were taken from the REACH II baseline interview, including relationship to the CR, age, years providing care, CG gender, education, employment status, and whether the CG was employed outside the home (Table 1). Caregivers were coded as either “spouse” or “nonspouse” for the final analyses based on the importance of this distinction in the caregiving literature (e.g., Miller & Guo, 2000). Unlike other constructs in the model, context variables were not considered to be a unitary construct and were not collapsed into a single latent variable.

Table 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of Coping–Stress Measurement Model

| CFA Model |

||

| Latent and observed variables | λ | R2 |

| Objective stressors | ||

| Behavior problems | .23 | .05 |

| ADL | .45 | .20 |

| IADL | .83 | .69 |

| MMSE | .04 | .00 |

| Subjective stressors | ||

| Burden | .84 | .71 |

| Conditional bother | .68 | .46 |

| ADL daily bother | .51 | .26 |

| IADL daily bother | .59 | .35 |

| Vigilance hours on duty | .08 | .01 |

| Role strains | ||

| Income adequacy | .35 | .12 |

| Negative social support | .54 | .29 |

| Intrapsychic strains | ||

| RMBPC confidence | .36 | .13 |

| Risk assessment | .62 | .38 |

| Positive aspects of caregiving | .38 | .14 |

| Resources | ||

| Religious coping | .23 | .05 |

| Social support network | .70 | .49 |

| Social support satisfaction | .67 | .45 |

| Risk assessment | .14 | .02 |

| Negative outcomes | ||

| Well-being | .85 | .72 |

| Subjective health | .38 | .14 |

| Health relative to 6 months ago | .38 | .14 |

| CES-D | .78 | .61 |

| Desire to institutionalize | .33 | .11 |

Note: λ is the standardized factor loading of the observed variable on the latent construct. ADL = activity of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; RMBPC = Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological StudiesDepression.

Objective Stressors

Objective stressors represent the stimuli or behaviors related to the CR that trigger the emotional response or reaction in the CG (i.e., subjective stressors). We used the following indicators to define the latent variable.

Mini-Mental State Examination.—

The MMSE measured the cognitive status of the CR by providing a brief assessment of a person’s orientation to time and place, recall ability, short-term memory, and arithmetic ability. Scores range from 0 to 30, with scores equal to or less than 24 indicating cognitive impairment (Folstein et al., 1975).

Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist—Frequency.—

The Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist (RMBPC; Teri et al., 1992) assessed the presence of 24 problem behaviors that the CR may have exhibited in the past week (e.g., trouble remembering recent events, asking the same question over and over). Caregivers rated the frequency of problem behaviors on a 4-point scale from 0 = not in the past week to 3 = daily or more often. A sum “frequency of problem behaviors” score is totaled and used as an objective measure of the presence of behavioral problems related to the dementia diagnosis. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .81.

ADL and IADL Scale—Frequency.—

The seven-item ADL scale (Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample = .84; Katz et al., 1963) assessed the CR’s ability to perform basic tasks of daily functioning independently (e.g., bathing, dressing, toileting, eating, grooming, transfer). Similarly, the eight-item IADL scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .76; Lawton & Brody, 1969) assessed the assistance needed to perform higher-level tasks such as shopping, operating the telephone, preparing meals, doing housework or laundry, and managing finances or medications. Total level of assistance needed for ADLs and IADLs were summed separately, with higher scores indicating more functional impairment.

Subjective Stressors

Subjective stress included caregiving burden, emotional bother related to providing for the CR’s daily care needs, behavioral bother, and vigilance.

RMBPC Conditional Bother Score.—

In the presence of a problem behavior (see RMBPC previously), CGs reported how bothered or upset they were by each behavior using a 5-point scale from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely (Teri et al., 1992). The conditional bother score was calculated by dividing the sum “bother” scores by the total frequency of behavior problems (Gitlin et al., 2005). The final score had a range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater bother. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .86.

Zarit Caregiver Burden Inventory.—

The 12-item abbreviated version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Inventory (Cronbach’s alpha = .85; Zarit, Orr, & Zarit, 1985; Bedard et al., 2001) was used to assess burden associated with caregiving (e.g., not enough time for oneself, not as much privacy). Caregivers rated each item on a 5-point scale from 0 = never to 4 = nearly always. Scores range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating higher reported burden.

Vigilance (REACH investigators).—

Vigilance was conceptualized as role captivity, referring to the amount of time the CGs believe they are required to supervise, provide care, and be “on duty” for the CRs. A single item (i.e., “About how many hours a day do you feel the need to ‘be there’ or ‘on duty’ to care for (CR)?”) indicated greater vigilance with more “on-duty” hours.

Daily Care Bother.—

Bother associated with the tasks of providing daily care or assistance with ADLs (Katz et al., 1963) was also computed (Gitlin et al., 2005). For each of the seven items of CG assistance, CGs reported their level of upset on a 5-point scale from 0 = no upset to 4 = extremely upset. A total CG upset score was found for daily care burden by averaging the amount of burden experienced across daily care tasks. Scores of average daily care burden can range from 0 to 4; higher scores indicate more burden. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .86.

Role Strain

The role strain latent variable encompasses the stressors related to maintaining multiple social, community, and work-related roles and includes the following indicators.

Income Adequacy (REACH investigators).—

Financial strain was measured by a single item assessing perceived difficulty in paying for basic needs such as food, housing, medical care, and heating along a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = not difficult at all to 3 = very difficult).

Social Support: Negative Interactions.—

Negative social support (e.g., others being critical, prying into affairs) was calculated from four items taken from the modified social support measure and rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = very often; Krause, 1995). Scores range from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating more negative social interactions. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .75.

Intrapsychic Strain

The infringement of the caregiving role into the CGs' ability to maintain a sense of personal identity was measured by confidence in caregiving, caregiving skills, and rewards associated with caregiving. The latent construct is coded such that higher values indicate less intrapsychic strain; a description of variables used to define the latent construct follows.

RMBPC: Confidence.—

The RMBPC Confidence (Teri et al., 1992) subscale assessed CG confidence in dealing with 24 problem behaviors that the CR may have exhibited in the past week. After rating the frequency of problem behaviors, CGs then assessed how confident they were in handling the target behavior on a 5-point scale from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely. A mean “confidence” score was calculated, with higher scores indicating more confidence. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .83.

Risk Appraisal: Caregiving Skills (REACH II investigators).—

Caregiver skills or mastery was assessed for eight items. Caregivers responded on a 3-point scale (0 = never to 2 = often) to questions regarding how hard or stressful it was to perform duties associated with caregiving (e.g., preparing meals, doing basic household chores). Higher scores indicate more mastery on a scale from 0 to 6. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .66.

Positive Aspects of Caregiving.—

The nine-item Positive Aspects of Caregiving scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .92; Tarlow et al., 2004) presented statements about the CG’s mental or affective state in the context of the caregiving experience. Responses were provided on a 5-point scale (0 = disagree a lot and 4 = agree a lot) and were designed to assess the perception of benefits within the caregiving context such as feeling more useful and feeling appreciated. Scores range from 0 to 36, with higher scores representing more positive appraisals of the caregiving situation.

Resources

Indicator variables for the resources latent construct include perceived social support, religious coping strategies, and caregiving knowledge.

Social Support Satisfaction and Network.—

Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health study investigators modified a social support measure assessing satisfaction, network, and negative interactions from several previous measures of social support and interactions (Barrera, Sandler, & Ramsey, 1981; Krause, 1995; Krause & Markides, 1990; Lubben, 1988). Satisfaction was assessed across three items tapping satisfaction with the amount of help received from social support networks (i.e., help with transportation, providing comfort, and making suggestions). Scores range from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating more satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .76. Similarly, social network was assessed across two items, on a 6-point scale, with categories for the number of network members (none, one, two, three or four, five to eight, nine or more). Scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating larger social networks.

Religious and Spiritual Coping (modified by the REACH investigators).—

Caregivers rated religious and spiritual coping for six items assessing the extent that religious or spiritual beliefs affect their caregiving (i.e., working with God as partners or wondering whether God has abandoned them; Pargament et al., 1998). Caregivers rated items on a 4-point scale from 0 = a great deal to 3 = not at all. Higher scores indicated greater religious and spiritual coping. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .75.

Risk Appraisal: Education (REACH II investigators).—

Caregivers rated access to information about memory loss, Alzheimer's disease, living wills, and durable power of attorneys for four items (i.e., 0 = no and 1 = yes). Scores summed across the four items result in a range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater education or access to information regarding topics associated with caring for a loved one with dementia. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .60.

Negative Outcomes

Risk Appraisal: Emotional and Physical Well-being (REACH II investigators).—

Emotional and physical well-being of the CG was assessed across eight items assessing occurrence of physical and emotional markers of health and well-being. Example items include the following: “In the past month, has caregiving made you feel overwhelmed or extremely tired?” and “Is it hard for you to have quiet time for yourself or time to do things you enjoy?” Scores range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating higher well-being. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .77.

Caregiver Health and Health Behaviors.—

Two items from the Caregiver Health and Health Behaviors (Schulz et al., 1997) measure were used in this analysis to assess subjective health. On the first item, CGs rated their health in general on a 5-point scale from excellent to poor. Scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating better perceived health. On the second item, CGs were asked to rate their health compared with that 6 months ago using the same scale, which represents a perceived change in health over previous months.

Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale.—

Caregiver depression was assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) (Cronbach’s alpha = .82), which asks about the frequency with which respondents have experienced depressive symptoms within the past week (e.g., “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me,” “I felt that everything I did was an effort”). Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating elevated levels of depressive symptoms. A score of 16 or greater indicates that the individual may have clinically significant depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977).

Desire to Institutionalize.—

The CG’s desire to institutionalize the CR in the past 6 months was assessed across six yes/no items (e.g., taken steps toward placement, consider nursing home; Morycz, 1985). Scores range from 0 to 6, with greater scores indicating an increased desire to institutionalize the CR. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .73.

Data Analysis

Missing values were handled according to REACH II guidelines. For cases missing less than 25% of items on a given scale, mean imputation was used to replace the missing value. If an individual missed more than 25% of items on any one of the measures, the data were excluded. A total of 33 of 642 participants were excluded from the analyses.

The first goal of this study was to examine the ability of the Pearlin model (Figure 1) to explain the global pattern of findings in the REACH II data. Structural equation modeling was used because a large-sample study was available and included multiple measures of each of the constructs in the model. However, one important feature of the Pearlin model is that resources are seen to moderate the relation between constructs (Figure 1). Any attempt to implement this model statistically must include these proposed interaction effects to provide a valid examination of Pearlin’s theory. Although interaction effects have not commonly been examined in SEM, Jöreskog (2000) describes a technique termed the “latent variable approach.” In this approach, SEM is first used to estimate values of the latent variables in the model from observed measurements. These latent values are then saved to a data set, and the relations among them are then examined using regression analysis. The latent variable approach therefore separates the estimation of the measurement model from the estimation of the structural model, which are usually performed at the same time in traditional SEM.

In our implementation of this technique, we first estimated the relations between the observed variables and the latent constructs using LISREL 8.54 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996; see Table 1). We used these estimates to generate scores on the latent constructs for each participant, which were then imported into SPSS 13.0. Before testing the model using a series of regressions, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to describe racial differences in the estimates of the latent constructs. The latent constructs were then used to estimate a series of regression models representing the paths in the modified Pearlin model (Figure 1). Values for the latent constructs were centered and standardized prior to testing interaction effects in accordance with recommendations by Aiken and West (1991). Caregiving context variables were not combined into a single latent construct because it would be logically inappropriate to use one value to represent the entire collection of context variables. Instead, these variables were entered into each model individually.

The primary aim of the study, testing the predictive ability of the Pearlin model as a whole, was addressed by examining both the fit of the SEM and the explanatory abilities of the regression models. The secondary aim of the study, determining whether the predictive ability of the Pearlin model varies by race, was addressed by determining whether the relations between the latent constructs in the regression models were significantly moderated by race. For the sake of space, post hoc analyses for each regression are described in the Discussion section, but specific statistics are not reported.

Results

Estimating the Measurement Model

The confirmatory factor analysis suggested the measurement model was fit, using LISREL 8.54 with a maximum likelihood estimation method (Table 1). The values of R2 indicated the reliability of each observed measure with respect to its underlying latent construct. All factor loadings were found to be statistically significant, except for MMSE and vigilance. The overall measurement model fit was acceptable, as indicated by the standardized root mean square residual (07) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; .07; Kenny, 2008). Our analysis makes the assumption that the latent variables are defined consistently across racial groups. To examine whether this is appropriate, we tested the measurement invariance between an unconstrained model for all groups and a constrained model in which factor loadings are held equal across groups (Schumacker & Lomax, 2004). Although the test revealed that there is a significant chi-square difference, χ2(34) = 274.51, p < .05, the actual difference in global fit indexes was minimal (i.e., the unconstrained model: RMSEA = .07; and the constrained model: RMSEA = .08). Because the focus of this article was to test how race or ethnicity affects the relations among the latent variables, using different measurement models would complicate any differences we see at the structural level, making any interactions with race difficult to interpret.

Descriptive Analyses

Descriptive analyses by race for the estimates of the latent constructs were performed using ANOVA and revealed significant racial differences by group for all the latent constructs (see Table 2). Each of the constructs significantly differed across the racial groups.

Table 2.

Differences in the Estimates of the Latent Construct by Race or Ethnicity Using Analysis of Variance

| Stress process model latent construct | Caregiver race/ethnicity, M (SD) |

||

| White/Caucasiana, n = 212 | Black/African Americana, n = 201 | Hispanic/Latinoa, n = 196 | |

| Objective stress* | −0.006 (0.22) | −0.028 (0.21) | 0.035 (0.17) |

| Subjective stress* | 0.166 (0.69) | 0.01 (0.67) | −0.189 (0.68) |

| Role strain* | −0.112 (0.67) | 0.136 (0.73) | −0.018 (0.66) |

| Intrapsychic strain* | 0.17 (0.6) | −0.09 (0.59) | −0.091 (0.66) |

| Resources* | 0.049 (0.26) | 0.038 (0.24) | −0.091 (0.26) |

| Negative outcomes* | 0.097 (0.78) | −0.12 (0.77) | 0.019 (0.91) |

Notes: aThe mean value for each latent construct was standardized.

*p < .01.

Testing the Pearlin Model

To address the primary aim, four separate regression models were used to test the relations among latent constructs in the SPM for the overall sample. The first regression (Table 3), predicting objective stressors from caregiving context variables, revealed that the model was not significant, F(7, 601) = 1.22, p = .29; thus, caregiving context variables were not collectively a significant predictor of objective stressors. Although the overall model was not significant, CG age was significantly related to objective stressors, such that younger CGs reported more objective stress.

Table 3.

Predicting Objective Stressors Using the Original Pearlin Model

| Model without race |

Model with race |

|||||

| Predictors | β | t | Significance | β | t | Significance |

| CG gender | −.051 | −1.246 | .151 | −.050 | −1.203 | .229 |

| CG age | −.115 | −2.075 | .038 | −.107 | −1.936 | .053 |

| CG education | −.060 | −1.408 | .160 | −.025 | −0.535 | .593 |

| Relationship (spouse/nonspouse) | .051 | 0.962 | .336 | .046 | 0.856 | .392 |

| Years caring for CR | −.007 | −0.169 | .866 | −.016 | −0.399 | .690 |

| Employment status | .031 | 0.291 | .771 | .042 | 0.391 | .696 |

| Employed outside home | −.020 | −0.190 | .849 | −.012 | −0.115 | .908 |

| Black/African American | −.055 | −1.141 | .254 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | .076 | 1.463 | .144 | |||

| R2 | .014 | .025a | ||||

Notes: Alpha was set at p < .05; overall models predicting objective stress were not significant. CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient.

R2 change = .011 (p <. 05).

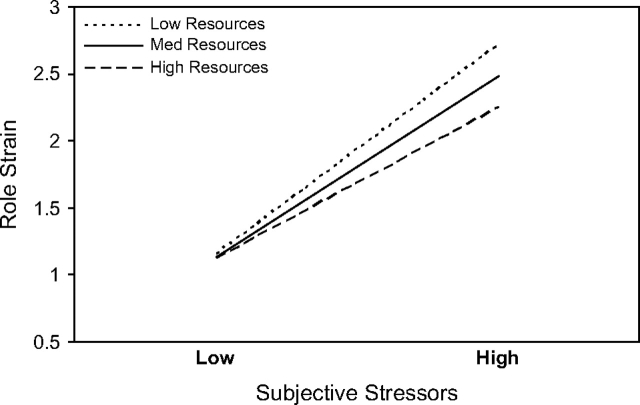

The second regression model (Table 4) predicts role strain from objective stressors, subjective stressors, resources, caregiving context variables, and the interaction between resources and subjective stressors. Results revealed that the overall model was able to predict variability in role strain, F(11, 597) = 27.55, p < .001. There were significant main effects of age, relationship, subjective stressors, and resources. Younger CGs, nonspouses, those experiencing more subjective stressors, and those with fewer resources experienced more role strain. There was also a significant interaction between resources and subjective stressors, such that the effect of stressors on role strain was magnified for those with fewer resources (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Predicting Role Strain Using the Original Pearlin Model

| Model without race |

Model with race |

|||||

| Predictors | β | t | Significance | β | t | Significance |

| CG context | ||||||

| CG gender | .011 | 0.331 | .740 | .020 | 0.582 | .561 |

| CG age | −.229 | −4.975 | <.001 | −.221 | −4.791 | <.001 |

| CG education | −.063 | −1.725 | .085 | −.063 | −1.624 | .105 |

| Relationship (spouse/nonspouse) | −.100 | −2.255 | .024 | −.075 | −1.682 | .093 |

| Years caring for CR | −.023 | −0.676 | .499 | −.020 | −0.595 | .552 |

| Employment status | −.173 | −1.947 | .052 | −.176 | −1.988 | .047 |

| Employed outside home | −.131 | −1.503 | .133 | −.142 | −1.631 | .103 |

| Black/African American | .138 | 3.367 | .001 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | .042 | 0.922 | .357 | |||

| Resources | ||||||

| Resources | −.164 | −4.530 | <.001 | −.180 | −2.920 | .004 |

| Resources × Subjective Stressors | −.091 | −2.596 | .010 | −.076 | −2.078 | .038 |

| Resources × Black/African American | −.059 | −1.242 | .215 | |||

| Resources × Hispanic/Latino | .058 | 1.091 | .276 | |||

| Objective stressors | ||||||

| Objective stressors | −.008 | −0.234 | .815 | .003 | 0.055 | .956 |

| Objective Stressors × Black/African American | .010 | 0.209 | .835 | |||

| Objective Stressors × Hispanic/Latino | −.021 | −0.481 | .631 | |||

| Subjective stressors | ||||||

| Subjective stressors | .347 | 9.320 | <.001 | .356 | 5.895 | <.001 |

| Subjective Stressors × Black/African American | −.024 | −0.502 | .616 | |||

| Subjective Stressors × Hispanic/Latino | .007 | 0.134 | .893 | |||

| R2 | .337 | .356a | ||||

Notes: Alpha was set at p < .05; overall models predicting role strain were significant. CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient.

R2 change = .020 (p <. 05).

Figure 2.

Subjective stressors by resources interaction on role strain (race not in the model).

Values of the latent construct are presented.

The third regression model (Table 5) predicts intrapsychic strain from role strain, resources, caregiving context variables, and the interaction between resources and role strain. Results revealed a significant overall model predicting intrapsychic strain, F(10, 598) = 25.88, p < .001. There were significant main effects of gender, relationship, education, role strain, and resources. Specifically, more role strain, fewer resources, being female, being a spouse, and more education were related to higher levels of intrapsychic strain.

Table 5.

Predicting Intrapsychic Strain Using the Original Pearlin Model

| Model without race |

Model with race |

|||||

| Predictors | β | t | Significance | β | t | Significance |

| CG context | ||||||

| CG gender | .201 | 5.704 | <.001 | .195 | 5.676 | <.001 |

| CG age | .051 | 1.066 | .287 | .038 | 0.814 | .416 |

| CG education | .214 | 5.948 | <.001 | .149 | 3.853 | <.001 |

| Relationship (spouse/nonspouse) | .149 | 3.329 | .001 | .104 | 2.332 | .020 |

| Years caring for CR | −.026 | −0.744 | .457 | −.019 | −0.561 | .575 |

| Employment status | .018 | 0.201 | .841 | .015 | 0.169 | .866 |

| Employed outside home | .048 | 0.536 | .592 | .051 | 0.581 | .562 |

| Black/African American | −.199 | −4.884 | <.001 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | −.223 | −5.015 | <.001 | |||

| Resources | ||||||

| Resources | −.344 | −9.345 | <.001 | −.266 | −4.315 | <.001 |

| Resources × Role Strain | −.029 | −0.800 | .424 | −.011 | −0.298 | .766 |

| Resources × Black/African American | −.053 | −1.083 | .279 | |||

| Resources × Hispanic/Latino | −.104 | −2.043 | .042 | |||

| Role strain | ||||||

| Role strain | .271 | 6.695 | <.001 | .371 | 5.503 | <.001 |

| Role strain × Black/African American | −.076 | −1.412 | .158 | |||

| Role strain × Hispanic/Latino | −.062 | −1.261 | .208 | |||

| R2 | .302 | .345a | ||||

Notes: Alpha was set at p < .05; overall models predicting intrapsychic strain were significant. CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient.

R2 change = .043 (p < .001).

The fourth regression model (Table 6) predicting negative outcomes from caregiving context variables, resources, intrapsychic strain, and interaction between resources and intrapsychic strain was also significant, F(10, 598) = 266.01, p < .001. Resources, intrapsychic strain, gender, and education were all significant predictors of negative outcomes. Specifically, CGs who were female and had lower education, fewer resources, and higher intrapsychic strain had more negative outcomes.

Table 6.

Predicting Negative Outcomes Using the Original Pearlin Model

| Model without race |

Model with race |

|||||

| Predictors | β | t | Significance | β | t | Significance |

| CG context | ||||||

| CG gender | .076 | 4.092 | <.001 | .075 | 4.041 | .000 |

| CG age | −.002 | −0.081 | .935 | −.005 | −0.226 | .821 |

| CG education | −.060 | −3.147 | .002 | −.049 | −2.413 | .016 |

| Relationship (spouse/nonspouse) | −.014 | −0.592 | .554 | −.009 | −0.369 | .712 |

| Years caring for CR | .005 | 0.256 | .798 | .002 | 0.094 | .925 |

| Employment Status | .077 | 1.659 | .098 | .074 | 1.575 | .116 |

| Employed outside home | .055 | 1.198 | .231 | .049 | 1.077 | .282 |

| Black/African American | .015 | 0.667 | .505 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | .040 | 1.652 | .099 | |||

| Resources | ||||||

| Resources | −.194 | −9.649 | <.001 | −.180 | −5.335 | .000 |

| Resources × Intrapsychic Strain | −.009 | −0.474 | .636 | −.008 | −0.424 | .672 |

| Resources × Black/African American | .005 | 0.189 | .850 | |||

| Resources × Hispanic/Latino | −.012 | −0.418 | .676 | |||

| Intrapsychic strain | ||||||

| Intrapsychic strain | .802 | 39.371 | <.001 | .781 | 22.702 | .000 |

| Intrapsychic Strain × Black/African American | −.001 | −0.019 | .985 | |||

| Intrapsychic Strain × Hispanic/Latino | .048 | 1.676 | .094 | |||

| R2 | .816 | .820a | ||||

Notes: Alpha was set at p < .05; overall models predicting negative outcomes were significant. CG = caregiver; CR = care recipient.

R2 change = .003.

Effects of Race Within the Pearlin Model

Four separate regression models were used to test whether each relation in the SPM differed across race. Each of these models contained all the effects that were originally proposed in the Pearlin model and included new terms representing the main effect of race as well as the interaction of each of the original effects with race. Post hoc analyses based on the adjusted means were used to explore significant race effects and interactions, but specific statistics are not reported for the sake of space. We did not add terms interacting race with the individual caregiving context variables.

Results from the first regression (Table 3) predicting objective stressors again revealed that the model was not significant, F(9, 599) = 1.739, p = .077, indicating that caregiving context variables were not related to objective stressors.

The second regression model (Table 4) predicting role strain was significant, F(19, 589) = 17.168, p < .001. There were significant main effects for race, CG age, employment status, subjective stressors, and resources. Younger CGs, CGs who were employed, those experiencing more subjective stressors, and those with fewer resources experienced more role strain. Post hoc analyses revealed that Black or African American CGs had significantly more role strain than White or Caucasian and Hispanic or Latino CGs. White or Caucasian CGs and Hispanic or Latino CGs were not significantly different in role strain. There was a significant interaction between resources and subjective stressors, such that the effect of stressors on role strain was again magnified for those with few resources.

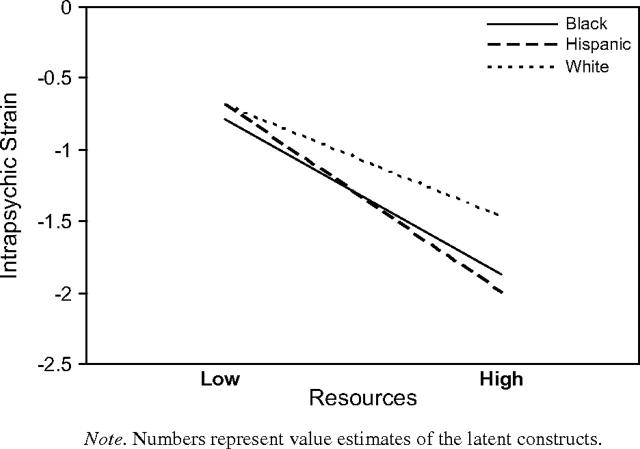

The third regression model (Table 5) predicting intrapsychic strain was significant, F(16, 592) = 19.497, p < .001. There were significant main effects for race, gender, relationship, education, role strain, and resources. Specifically, more role strain, fewer resources, being female, being a spouse, and more education were related to higher levels of intrapsychic strain. Post hoc analyses revealed that White or Caucasians had significantly greater intrapsychic strain than Black or African Americans and Hispanic or Latinos. Black or African Americans and Hispanic or Latinos were not significantly different in intrapsychic strain. The effect of race interacted with resources, such that CGs reported similar levels of intrapsychic strain across race at lower levels of resources, but White or Caucasians reported more intrapsychic strain than Black or African Americans or Hispanic or Latinos at higher levels of resources (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Race by resources interaction on intrapsychic strain. Numbers represent value estimates of the latent constructs.

The fourth regression model (Table 6) predicting negative outcomes was also significant, F(16, 592) = 167.994, p < .001. Resources, intrapsychic strain, gender, and education were all significant predictors of negative outcomes. Specifically, CGs who were female and had lower education, fewer resources, and higher intrapsychic strain had more negative outcomes.

Discussion

This study addressed two primary aims. To address the first aim, we used a combination of SEM and regression techniques to evaluate the SPM as proposed by Pearlin and colleagues (1990). Structural equation modeling revealed that the SPM obtains a satisfactory fit (i.e., a goodness of fit index of .90) across race or ethnicity in the REACH II data. To address the second aim, we incorporated race or ethnicity into Pearlin’s SPM by examining race as a moderator of the relation between each of the latent constructs (Figure 1). We found that each pathway is significant except for the one predicting objective stress from caregiving context (Figure 1) and the one predicting role strain from objective stress.

Findings support interventions, such as REACH II, that simultaneously target multiple aspects of the SPM across racial or ethnic groups. These analyses bolster theoretical and practice-based arguments for conceptualizing the caregiving context in an SPM framework such as the one proposed by Pearlin and colleagues (e.g., FCA, 2006; Pearlin et al., 1990). Although the current analyses did not directly test the relation between primary stressors and mental health variables, our analyses suggest that assessing subjective stressors is essential when predicting role strain (Table 4).

It is noteworthy that, similar to Gallagher-Thompson and Powers (1997), objective stressors did not significantly predict secondary role strain or negative mental health outcomes. This may suggest that a decreased emphasis on CR characteristics would be appropriate when the CG’s mental health is the focus of intervention. In other words, when time and resources are limited, reducing assessment related to the CR may facilitate a more time-efficient evaluation and intervention.

Although the SPM as a whole appears to fit the caregiving experience across racial or ethnic groups, supplemental analyses found significant differences in all the individual components: objective stress, subjective stress, role strain, intrapsychic strain, resources, and negative outcomes by race (Table 2). (Racial differences in the estimates of the latent constructs are described using ANOVA and are presented in Table 2. These analyses are not directly related to the aims of this study and therefore are not a primary focus.) Strengths and vulnerabilities for each race or ethnicity vary considerably, suggesting that interventions must target different nuanced aspects of the stress process to provide optimal benefit for individuals of different cultural or ethnic backgrounds. Specifically, White or Caucasians experienced significantly greater intrapsychic strain than Black or African Americans and Hispanic or Latinos, suggesting that they might benefit most from interventions that target intrapsychic concerns (e.g., learning to manage negative emotions).

In contrast, among the Hispanic or Latinos, high levels of resources seem more protective in reducing levels of intrapsychic strain than among White or Caucasians. This suggests a different intervention target, such as increasing knowledge about dementia and access to services. Gray, Jimenez, Tong, and Gallagher-Thompson (in press) found that Hispanic or Latinos had significantly less accurate information about dementia causes and treatments and were more likely to use nonmedical interventions for themselves and their CRs compared with White or Caucasians. Thus, programs that include education about dementia, as well as culturally and linguistically appropriate resources, would likely yield benefits for this group.

For African Americans, interventions that target role strain (e.g., negative social support) may prove to be most helpful. This is a complex issue for this group because these CGs tend to be younger, employed, and taking care of their own families. Programs that focus on improving communication skills among family members might be further developed for this group. For example, family interventions such as the creation of legacies to represent the life accomplishments of older adults are effective in improving family communication, reducing stress, and increasing CRs’ sense of meaning in life (Allen, Hilgeman, Ege, Shuster, & Burgio, in press). Additionally, Gitlin et al. (2003) found that education, problem-solving training, and adaptive equipment provided by occupational therapists to make the home environment safer and more “user friendly” for the demented person resulted in significant improvements in CG stress and depression among African American CGs.

One limitation of the current study is that we have combined Hispanic or Latino CGs from different cultural subgroups—primarily, Cuban American and Mexican American individuals were recruited at the Miami and Palo Alto sites, respectively. These two groups have distinct cultures, despite speaking the same language, and may appraise the caregiving situation differently (Yeo & Gallagher-Thompson, 2006). Furthermore, acculturation (e.g., Kao & Travis, 2005) and cultural justifications for caregiving (e.g., Dilworth-Anderson, et al., 2005) should also be considered as potential moderators in the stress process. We suggest that future research should limit samples to one group and include measures of acculturation and cultural influences when possible. More research is also needed on intragroup subtleties in the link between stressors and emotional and physical outcomes.

Another limitation is the acceptable rather than good fit of the measurement model used in the analyses, which suggests that the model as measured in the current study has room for improvement. Additionally, several indicators (e.g., MMSE, vigilance hours on duty) had nonsignificant loadings on their latent constructs. Given that we tested an established conceptual model that has designated indicators for each latent construct, it is possible that some indicators might not adequately capture the construct for reasons such as poor measures and nonlinear relations. For example, there is evidence that cognitive impairment (i.e., MMSE) functions nonlinearly as a stressor (Gwyther, 2007) over the course of the disease, which would affect its statistical relation to other indicators of the latent construct. Similarly, hours on duty (i.e., vigilance) is based on CGs’ self-report. Measures like this one that rely solely on an individual’s memory of a given event make it easily susceptible to the influences of social desirability factors. Future studies may want to test a modified model by removing nonstatistically significant indicators or those with low R2 values.

Clearly, “tailoring” interventions to fit the expressed needs and problems of ethnically and culturally diverse CGs has been recommended by many researchers (e.g., Gallagher-Thompson, Haley, et al., 2003; Hilgeman, Allen, DeCoster, & Burgio, 2007). The findings of this study suggest empirically derived and ethnically specific domains for intervention that should be informative for future research in this field. Ideally, tailored interventions based on needs assessments, such as the REACH II trials (Belle et al., 2006), may be the most appropriate. However, researchers and clinicians can use a conceptual framework like the one presented here to initiate intervention when family-specific information is not available or would be too expensive to collect.

Funding

REACH II was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research (AG13305, AG13289, AG13313, AG20277, AG13265, and NR004261).

Acknowledgments

A detailed description of the REACH II study design, methods, assessment instruments, and original de-identified data are available to the public at the National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging (http://webapp.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/NACDA-Study/04354.xml). The Study Manual of Operations, which contains detailed information about the intervention, including resource and training materials, is also available at www.edc.pitt.edu/reach2/public/manuals.html. REACH II was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research (AG13305, AG13289, AG13313, AG20277, AG13265, and NR004261).

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Hilgeman MM, Ege MA, Shuster JL, Burgio LD. Legacy activities as interventions approaching the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11:1029–1038. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda MP, Knight BG. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist. 1997;37:342–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Sandler IN, Ramsay TB. Preliminary development of a scale of social support: Studies of college students, American Journal of Community Psychology, 1981;9:435–443. [Google Scholar]

- Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois L, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SC, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Brummett BH, Goodwin P, Williams SW, Williams RB, Siegler IC. Effect of race on cultural justifications for caregiving. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:S257–S262. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.s257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Goodwin P, Williams SW. Can culture help explain the physical health effects of caregiving over time among African American caregivers? Journals of Gerontology: Social Science. 2004;59:S138–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: A 20-year review (1980-2000) Gerontologist. 2002;42:237–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver assessment: Voices and views from the field. Report from a National Consensus Development Conference. Vol. 2. San Francisco: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Haley W, Guy D, Rupert M, Arguelles T, Zeiss L, et al. Tailoring psychological interventions for ethnically diverse caregivers. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:423–438. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Powers DV. Primary stressors and depressive symptoms in caregivers of dementia patients. Aging and Mental Health. 1997;1:248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Roth DL, Burgio LD, Loewenstein DA, Winter L, Nichols L, et al. Caregiver appraisals of functional dependence in individuals with dementia and associated caregiver upset: Psychometric properties of a new scale and response patterns by caregiver and care recipient characteristics. Journal of Aging and Health. 2005;17:148–171. doi: 10.1177/0898264304274184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Corcoran M, Dennis MP, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW. Effects of the home environmental skill-building program on the caregiver–care recipient dyad: 6-month outcomes from the Philadelphia REACH initiative. Gerontologist. 2003;43:532–546. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray H, Jimenez D, Tong H-Q, Gallagher-Thompson D. Ethnic differences in beliefs regarding Alzheimer's disease among dementia family caregivers. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ad4f3c. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwyther L. Working with the family of the older adult. In: Blazer D, Steffens DC, Busse EW, editors. Essentials of geriatric psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2007. pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, Lamond LA, Han B, Burton AM, Schonwetter R. Predictors of depression and life satisfaction among spousal caregivers in hospice: Applications of a stress process model. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2003;6:215–224. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, Roth DL, Coleton MI, Ford GR, West CAC, Collins RP, et al. Appraisal, coping, and social support as mediators of well-being in Black and White family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:121–129. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgeman MM, Allen RS, DeCoster J, Burgio LD. Positive aspects of caregiving as a moderator of treatment outcome over 12 months. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:361–371. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG. Latent variable scores and their uses. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2000. Retrieved May 23, 2007, from http://www.ssicentral.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kao HS, Travis SS. Effects of acculturation and social exchange on the expectations of filial piety among Hispanic/Latino parents of adult children. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2005;7:226–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2005.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford A, Moskowitz R, Jackson B, Jaffe M. Studies of illness and the aged: The index of ADL, a standardized measure of biological and psychological function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Measuring model fit. 2008, January 29. Retrieved July 18, 2008, from http://davidakenny.net/kenny.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Negative interaction and satisfaction with social support among older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1995;50:p59–p73. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.2.p59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Markides KS. Measuring social support among older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1990;30:37–54. doi: 10.2190/CY26-XCKW-WY1V-VGK3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M, Brody E. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Rajagopal D, Brody E, Kleban MH. The dynamics of caregiving for a demented elder among black and white families. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1992;47:S156–S164. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.4.s156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Family and Community Health. 1988;11:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Guo S. Social support for spouse caregivers of persons with dementia. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;55:S163–S172. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.3.s163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morycz RK. Caregiving strain and the desire to institutionalize family members with Alzheimer's disease. Research on Aging. 1985;7:329–361. doi: 10.1177/0164027585007003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Zinnbauer BJ, Scott AB, Butter EM, Zerowin J, Stanik P. Red flags and religious coping: Identifying some religious warning signs among people in crisis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998;54:77–89. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199801)54:1<77::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2005;45:90–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health II. 2004–2006. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00177489 [Data file] Retrieved from ClinicalTrials.gov Web site: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00177489. [Google Scholar]

- Roff LL, Burgio LD, Gitlin L, Nichols L, Chaplin W. Positive aspects of Alzheimer's caregiving: The role of race. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:P185–P190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Gallagher-Thompson D, Haley W, Czaja SJ. Understanding the interventions process: A theoretical/conceptual framework for intervention approaches to caregiving. In: Schulz R, Ory M, editors. Handbook of dementia caregiving. New York: Springer; 2000. pp. 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Newsom JT, Mittlemark M, Burton L, Hirsh C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: The caregiver health effects study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;12:110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’ guide to structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tarlow BJ, Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Rubert M, Ory MG, Gallagher-Thompson D. Positive aspects of caregiving, contributions of the REACH project to the development of a new measure for Alzheimer's caregiving. Research on Aging. 2004;26:429–453. [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit S, Vitaliano PP. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (RMBPC) Psychology and Aging. 1992;18:375–384. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D, editors. Ethnicity and the dementias. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Orr NK, Zarit JM. Families under stress: Caring for the patient with Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. New York: New York University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]