Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this article was to explore staff–family relationships in assisted living facilities (ALFs) as they are experienced by care staff and perceived by administrators. We identify factors that influence relationships and explore how interactions with residents’ families affect care staff’s caregiving experiences. Design and Methods: The data are drawn from a statewide study involving 45 ALFs in Georgia. Using grounded theory methods, we analyze qualitative data from in-depth interviews with 41 care staff and 43 administrators, and survey data from 370 care staff. Results: Care workers characterized their relationships with most family members as “good” or “pretty good” and aspired to develop relationships that offered personal and professional affirmation. The presence or absence of affirmation was central to understanding how these relationships influenced care staffs’ on-the-job experiences. Community, facility, and individual factors influenced the development of relationships and corresponding experiences. Insofar as interactions with family members were rewarding or frustrating, relationships exerted positive or negative influences on workers’ caregiving experiences. Implications: Findings suggest the need to create environments—through policy and practice—where both parties are empathetic of one another and view themselves as partners. Doing so would have positive outcomes for care workers, family members, and residents.

Keywords: Staff–family relationships, Assisted living, Caregiving, Long-term care

Nearly one million Americans live in assisted living facilities (ALFs), which are residential care settings that provide board, 24-hr protective oversight, and non-medical care (Mollica & Johnson-LaMarche, 2005). Presently, the industry is plagued with high turnover rates and retention problems among its direct care workers (Friedland, 2004). Overwhelmingly women, these workers who provide the bulk of resident care usually receive low wages and have relatively low occupational status. Retention problems alongside predicted worker shortages and a desire for quality care and work environments underscore the need to understand care workers' experiences, particularly the factors that influence their satisfaction and retention in ALFs.

Long-term care (LTC) research suggests that workplace relationships, especially those between caregiver and care recipient, are significant in this regard. Studies in home care settings (Ball & Whittington, 1995; Chichin, 1992; T. X. Karner, 1998; Parks, 2003), nursing homes (NHs; Bowers, Esmond, & Jacobson, 2000), and ALFs (Ball, Lepore, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Sweatman, 2009; Ball et al., 2005) show that close, family-like ties often develop between elders and their paid caregivers and that these relationships lead to improved quality of care and life for care recipients and are personally meaningful for caregivers and among the most fulfilling aspects of their jobs. Although these relationships typically take primacy over those between workers and care recipients’ family members, families are an important part of the work environment. Families are apt to influence care workers’ day-to-day experiences; yet, relationships with families remain underresearched, particularly in ALFs.

Existing research on families in ALFs primarily focuses on satisfaction (e.g., Dobbs & Montgomery, 2005) or their roles, documenting the type and frequency of, as well as variation in, resident support (for a recent review, see Gaugler & Kane, 2007), rather than relationships with care staff. Consequently, much of what is known about staff–family interactions in residential care settings comes primarily from research in NHs. Yet, ALFs do not provide skilled care and, compared with NHs, serve less impaired resident populations, require lower staff-to-resident ratios, and have fewer training requirements (Hawes, Rose, & Phillips, 1999). Such differences potentially affect relational dynamics. Nevertheless, in the absence of studies, NH research provides insight into what relationships might be like in ALFs.

Nursing home research indicates that staff–family relationships range from low to high in degree of closeness, openness, and levels of collegiality (Gladstone & Wexler, 2002a, 2002b). Reports of staff attitudes toward family members vary from positive to negative and are often ambiguous. For instance, registered nurses and certified nursing assistants (CNAs) typically view family members as valuable resources whose assistance is appreciated, but some are perceived as too demanding, disruptive, or inadequately involved in residents’ lives (Foner, 1994; Hertzberg, Ekman, & Axelsson, 2003; Shield, 2003). Parallels can be found in the home care literature regarding aides’ attitudes toward client’s family members (Chichin, 1992; Parks, 2003).

Existing research identifies certain factors that account for variability in staff–family relationships. These factors pertain to the facility as a whole as well as to families, staff, and residents. At the facility level, the presence or absence of a family council, provision of education and counseling, and policies and practices aimed at influencing family involvement make some facilities more family-oriented than others (Friedemann, Montgomery, Mailberger, & Smith, 1997). Given that relationships develop within the context of family involvement, the frequency and nature of family activity influences interactions with staff. Family members’ behaviors also affect relationships. Care workers report positive relationships when they feel appreciated and recognized by family members, rather than chastised or attacked (Gladstone & Wexler, 2002a; Shield, 2003). Workers find it particularly difficult to deal with family members who they feel have unrealistic expectations or do not understand NH work or workloads (Shield, 2003). Racial and social class differences can influence relationships, for example, as Black nurse’s aides report racist behaviors among some White family members (Berdes & Eckert, 2001; Foner, 1994). Care workers’ attitudes and behaviors are also influential. One’s investment in professional identity, notions of acceptable workplace relationships (Gladstone & Wexler, 2002a), degree of empathy toward family members (Sandberg, Nolan, & Lundh, 2002), and willingness or ability to build trust (Shield, 2003) appear to influence relationships. In one study involving both NHs and ALFs, closeness to residents was a significant predictor of staff attitudes toward families (Gaugler & Ewen, 2005). For their part, residents can influence staff–family relationships by “smoothing” things out, calming down family members, or relaying information between the parties (Shield, 2003, p. 210). In Shield’s study, one resident intervened by explaining care workers’ job description to their family members.

Researchers consistently indicate the importance of developing effective partnerships between staff and family members (see Gaugler, 2005a). Recent intervention studies have sought to educate both parties to improve relations and outcomes for NH residents, families, and staff. In one study, care workers were less likely to leave their jobs while workshops aimed at improving listening and communication skills were in process (Pillemer et al., 2003). In another study conducted in dementia care units (DCUs), Robison and colleagues (2007) found that workshops reduced staff reports of conflict with families and feelings of depression.

Although a body of work has addressed the relationships between direct care workers and residents’ families in NHs, such research is lacking in ALFs. The current and predicted LTC workforce challenges and the growing demand for ALFs and quality care underscore the need to attend to this gap. Therefore, we ask the following: (a) How do direct care workers perceive their relationships with residents’ family members? and (b) What factors influence relationships? Answering these questions will lead to a greater understanding of how care workers experience their jobs, including how relationships with families influence their ability to care and their attitudes toward care work.

Methods

The data come from the study “Job Satisfaction and Retention of Direct Care Staff in Assisted Living,” which involved a stratified random sample of 45 ALFs with 16 beds or more located in Georgia. Using a mixed-methods approach, the study examined the meaning of job satisfaction for direct care staff and factors influencing their satisfaction and retention. Facilities served predominately White resident populations and ranged in size, location, participation in Medicaid-waiver programs, and the presence of DCUs (see Table 1). The project was approved by Georgia State University’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Selected Facility Characteristics by Facility Size

| Characteristic | Small (16–25 beds, n = 18) | Medium (26–50 beds, n = 13) | Large (51+ beds, n = 14) | Total (n = 45) |

| Medicaid waiver (%) | 50 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Urban (%) | 56 | 77 | 100 | 66 |

| Dementia care unit (%) | 0 | 31 | 77 | 31 |

| White residents (%) | 93 | 94 | 97 | 95 |

We conducted semistructured qualitative interviews with 44 administrators (2 managed 1 ALF; 1 managed 3 ALFs). Interviews explored all aspects of facility life influencing care workers’ work experiences. We probed for organizational structure and administrators’ perspectives on workers’ experiences, attitudes, and workplace relationships, including those with residents’ families. Specifically, we inquired about staff–family interactions and policies and procedures regarding relationships.

We randomly selected 370 direct care workers to participate in interviews, with a refusal rate of 10%. Interviews included both fixed-choice and open-ended questions and addressed personal characteristics, education, work history, and workplace relationships, experiences, and attitudes. One open-ended question, “What kind of relationship do you most value with residents’ family members?”, is used in this analysis.

Forty-one direct care workers from 39 facilities participated in in-depth qualitative interviews. The lead researcher in each home (the second, third, and fourth authors) purposively selected participants based on variation in race, ethnicity, nativity, age, education, gender, marital status, employment history, shift, and full- or part-time status. Four declined participation. With consent, we recorded interviews and transcribed them verbatim. Lasting an average of 1.5 hr, interviews explored workers’ earlier lives, including employment histories, and their job experiences, and relationships. Regarding residents’ family members, we asked participants to describe their relationships in general, those they considered close or problematic, their strategies for getting to know families and improving relations, and their perceptions of how interactions affect satisfaction. Eleven workers completed both types of interviews, yielding a total sample of 400.

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 provides information about our direct care worker sample, distinguishing between survey and interview participants. Almost all were women. Over half were Black and most were native born. Workers ranged in age from 18 to 75 years, with a mean of 40 years (not shown). More than half were unmarried. Education varied, with 55% having CNA training. Workers were employed an average of 7.8 years in LTC and 2.5 years at their current facility. Table 3 provides information about the administrators. Most were women and White and had some college education or greater. Administrators were employed an average of 13 years in LTC and 6.3 years in their current ALF.

Table 2.

Personal Characteristics of Direct Care Staff by Data Type

| Characteristic | Survey participants (n = 370), % | Interview participants (n = 41), % | Total sample (n = 400), % |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 99 | 95 | 99 |

| Race | |||

| Black | 57 | 54 | 57 |

| White | 39 | 41 | 39 |

| Other | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Nativity | |||

| U.S. | 81 | 85 | 82 |

| Caribbean | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| African | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| Other | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–25 | 17 | 10 | 17 |

| 26–35 | 24 | 20 | 24 |

| 36–45 | 22 | 20 | 21 |

| 46–55 | 25 | 26 | 25 |

| 56–65 | 10 | 19 | 11 |

| >65 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 39 | 37 | 39 |

| Never married | 29 | 37 | 31 |

| Divorced | 20 | 17 | 19 |

| Separated | 8 | 2 | 7 |

| Widowed | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| Education/training | |||

| Less than high school | 16 | 27 | 16 |

| High school diploma/GED | 47 | 39 | 47 |

| Trade school | 8 | 5 | 8 |

| Some college/associate degree | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| College degree | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Certified nursing assistant training | 55 | 51 | 56 |

| Years employed in | |||

| Long-term care (M, MD) | 7.9, 5.0 | 8.4, 7.0 | 7.9, 5.0 |

| Facility (M, MD) | 2.4, 1.5 | 3.5, 2.9 | 2.5, 1.6 |

Note: MD = Median.

Table 3.

Personal Characteristics of Administrators (n = 44)

| Characteristic | % or M (SD) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 70 |

| Race | |

| Black | 11 |

| White | 87 |

| Other | 2 |

| Age (years) | 47 (10.86) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 5 |

| High school diploma/GED | 12 |

| Trade school | 5 |

| Some college/associate degree | 33 |

| College degree | 22 |

| Some postgraduate | 2 |

| Graduate degree | 21 |

| Long-term care training | |

| Certified nursing assistant training | 14 |

| Licensed practical nurse | 9 |

| Registered nurse | 17 |

| Assisted living administrator license | 16 |

| Employment history (years) | |

| Long-term care | 13.2 (9.23) |

| Assisted living | 8.7 (6.21) |

| Facility | 6.3 (6.17) |

| Administrative experience | 11.2 (8.45) |

Data Analysis

We analyzed qualitative data from administrator and worker interviews and responses to the open-ended survey question about residents’ families following the principles of grounded theory methods (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We began the three-stage approach by “fracturing” the data line by line for emergent categories based on our research questions and issues raised by participants in a process referred to as open coding. Initial codes included quality of relationships, relational aspirations, factors influencing relationships, and relationship outcomes. In this phase, we considered administrator and staff data separately. Next, in axial coding, we linked open-coding categories to other categories signifying relationships, causal conditions, context, intervening conditions, and consequences. For example, we linked most valued relationship type to individual-, facility- and community-level factors such as workers’ approach to care, residents’ disability level and family support, facility size and family-related policies, and community location. At this stage, we interpreted staff and administrator data within the context of one another. In the final stage, we integrated and refined categories to form a larger conceptual scheme through selective coding and organized our categories around our core category, “global affirmation,” which was generated through our analysis.

Results

Staff Perceptions of Relationships With Family Members

“I get along with most of them.” These words reflect a typical viewpoint of care workers regarding their relationships overall with family members. The majority were depicted positively; some were not. Exploration of care workers’ accounts of preferred and actual relationships revealed further variations in the type of relationships workers both wanted and experienced.

A number of workers described “personal” relationships where family members became “an extension of the resident” as they grew to “care about them” in similar ways. One worker reflected on her connection with a resident’s daughter: “I think she is really comfortable with me. She’s always coming and anytime she hears my voice, she always smiles and says, ‘I know you’re here.’ That makes me feel like she is my sister.” Speaking more generally of family members she feels “close” to, she remarked, “Some of them regard you well, and that makes you feel good because they just don’t see you as taking care of their parent. They see you like someone in the family.”

This preference for closeness sometimes stemmed from workers’ own connections with residents, as expressed by one: “I’d like them to treat me like family because I treat their family member [the resident] as if I were their own family.” Being viewed “like someone in the family” elevated workers’ status and was satisfying.

Other workers preferred professional connections with families. One explained, “I like to keep it business-oriented because when you get more family-like, you talk more freely and that tends to cause more problems.” Still others viewed personal and professional approaches as overlapping and valued both characteristics, suggesting, “There’s a time and a place for both. Sometimes chatting, sometimes working.”

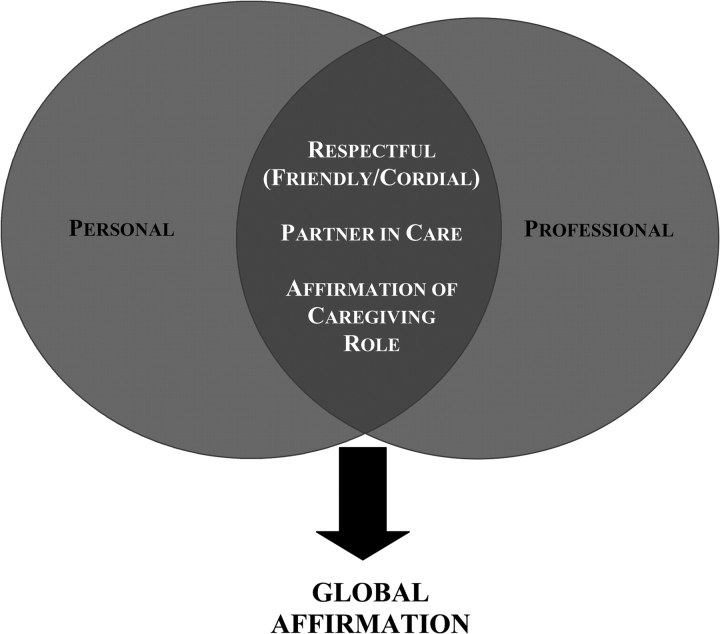

Whether achieved through personal or professional relationships or both, three key relational aspirations were indicated by our analysis: respectfulness, partnership in caregiving, and affirmation of the caregiving role (see Figure 1). First, at the most basic level, caregivers wanted families to be respectful. One worker stated, “Treat me like I’m human.” In this vein, staff preferred families be “cordial” and “speak and be nice and friendly.” Family members were perceived as “rude” or “very rude” when they ignored workers or were confrontational. One worker described a frustrating encounter:

We have one lady, actually her mother lost her glasses, and instead of saying, “Thanks for finding them” she was going off, she was yelling at the wrong person. I wasn’t even here. But she was fussing at me and I told her that I wasn’t here and [she] was like, “I don’t care who was here. Somebody better find my mama’s glasses.” Well, the glasses were found and she didn’t come back to say, “I’m sorry, thank you.” Nothing.

Figure 1.

Staff members' type of desired relationships with residents' family members.

Although not the norm, some Black workers reported direct and indirect racist behaviors on the part of family members. For example, an African-born caregiver experienced “being cursed out real bad” by a White resident using racial language. “The worst thing” for her was that “his family was there and they didn’t do anything about it.” This encounter left her feeling “bad” and unsupported.

Alongside respect, workers wanted families to be their partners in caregiving. From workers’ perspectives, this partnership involved “open” and “honest” communication, being available when needed, and providing the appropriate level of social, emotional, and material support to the resident. As one worker said, “We are here to do our part” and families “need to do” their “part.” Family support helped workers deliver the best possible care. Another elaborated:

What bothers me is not having what I need for the residents. That doesn’t fall on the facility. That falls on the family because they are supposed to supply what they need…. If they don’t have what they need, it is hard for me to [care for the resident].

Family support also influenced workers’ own well-being and care strategies, as one explained: “It makes you feel better when you see family that really care. It makes you want to go an extra length yourself.”

Conversely, families’ failures to engage in partnerships had a negative effect. Describing the most frustrating aspect of her job, one worker said, “The biggie is their family. Their family knows they are here. They know what state they’re in and they don’t even come and show their face. Not even a sufficient phone call, and that just really makes me ill.”

Lastly, care workers wanted families to affirm their role as professional caregivers. Affirmation involved trust and having an understanding of and respect for caregiving. One worker explained, “I want them to know that I am someone who takes care of their family member in a professional way.” Elaborating on her “pretty good” relationships, one explained:

I can call any family member and talk to them. They are fine if I call and tell them that I think she has been having accidents quite often so I think it is time that we start letting her wear pull-ups. You know, something like that, and they will say, “Okay, just use your best judgment.”

Affirmation also involved appreciation. One worker expressed a common sentiment: “They tell us how much they appreciate how much we do for their dad or mother. That makes our day, my day.” Appreciation, particularly involving recognition of job demands, made workers “feel proud” and affirmed their aptitude for caregiving.

Care workers believed most family members were appreciative of their efforts. One said:

Overall, I would say it is seventy-five percent of the people appreciating you for what you do. Most of the people that have their families here have the heart to say, “Thank you.” They say, “I don’t know how you do it.” They will look at you and say, “You do great work.”

In addition to verbal recognition, care workers valued more tangible actions such as baking cookies, writing notes, completing comment cards, advocating on behalf of workers, and, when allowed, gift giving. Such recognition was satisfying and affirming:

One thing about the comment cards, it is nice when they fill out something nice about you and put it in the box and you get the comment cards. I have gotten three of them and I saw it and was really impressed with myself and I’m like, “Oh, they saw that I did this good thing” and I feel so proud.

Administrators also reported that staff valued “positive feedback.” One administrator indicated that workers valued family recognition more than recognition from the facility:

We can go in there all day long and say we appreciate what they do and send little letters off in their paychecks, but I think when a family member—and we’re good, our family members are good about that, letting the ones know they really appreciate them taking care of their mom or dad or thank you for doing this extra thing for her. I think that’s like, “They noticed.”

Certain family members, though, were perceived as impossible to please and rarely, if ever, shown appreciation. As one worker said: “Some families complain no matter what you do.”

As illustrated in Figure 1, regardless of whether workers preferred a personal or professional approach, they desired connections with families that were respectful and involved caregiving partnerships and affirmation of the caregiver role. Taken together, such relational characteristics provided global affirmation by reinforcing the value and meaning of their work as well as their personal and professional identities. For this reason, global affirmation appears central to understanding the role families play in care work experiences in ALFs.

Relational Factors

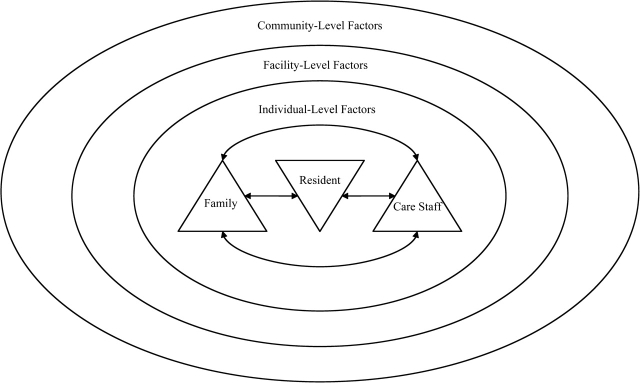

Our analysis yielded distinct yet interrelated factors influencing staff–family relationships. As show in Figure 2, factors operated on individual, facility, and community levels. Individual-level factors often exerted the greatest influence and include personal characteristics and behaviors relating to residents, staff, and family members. Facility-level factors involve facility characteristics, policies and practices, and administrator behaviors. Community-level factors pertain to population demographics and location. We discuss each type of factor below.

Figure 2.

Factors influencing staff–family relationships in assisted living.

Individual Factors.—

Resident factors.

Residents were typically the focal point of staff–family interactions, and their health characteristics, nature of family support, satisfaction, and behaviors influenced relationships. Residents’ health conditions affected interaction patterns. Families of residents with fewer care requirements tended to interact less with care staff than families of more impaired residents. Change in a resident’s health status often precipitated staff–family contact and communication. Residents with dementia, particularly those living in DCUs, usually had fewer family visits, which translated into fewer relational opportunities. According to one worker, sometimes families “can’t accept who their parents are and so they don’t come and see them.” Yet, when dementia or other conditions hampered a resident’s ability to communicate, caregivers perceived family involvement as essential. For example, “Back in the dementia [unit] when there is something wrong with the resident and they can’t tell you what it is . . . if I am in doubt, I always call the family member.” In some cases, residents’ resistant behaviors promoted collaborative caring relationships. A worker described one example: “He is stubborn, he don’t want to do anything . . . usually what we do in that case is we will call the family member and they come over and they talk with him.”

Resident satisfaction also was important. Echoing a common sentiment, one caregiver explained, “I think if the resident is not happy, the family will know it. If the family is not happy you will sure know it . . . . If the residents are happy, the family is going to be happy and it’s going to make the job easier.” Residents’ discussions about staff to family members influenced the development of staff–family relationships.

Staff factors.

The main staff factors influencing relationships related to their personal and job characteristics and their approaches to and connections with residents and families. Commonality of culture, race, or background typically promoted relationships involving empathy, respect, and appreciation, whereas differences could lead to guarded interactions. For example, an African-born worker employed in a large facility where most residents were White remarked, “At first you feel, maybe because I am Black or something and you don’t know how they will react about a Black person looking after their family.” Her reception was mostly positive, but she had experienced some racism, which negatively influenced relationships.

Certain job-related characteristics created variation. Staff who worked at night or in DCUs typically had less contact with families. One night-shift worker commented, “I see [families] at certain times, like if [residents] get sick they will come out here. I met [one resident’s] daughter for the first time when he passed away, but no, I don’t never get to see them.” Longer-tenured workers spoke of being more familiar with families, associating this familiarity with trust. One commented, “They really talk to me more anyways because I have been here almost five years.”

Most workers made efforts to initiate relationships by introducing themselves and getting to know families. One described her strategy:

I make it a priority to have a good relationship with the family . . . . Like certain ones of them, their family comes in here regularly, I just try to get a good relationship because it makes them feel better to know, or [it] would me, that somebody was taking care of my mother or father that was really outgoing and friendly and, you know, to know they are very well taken care of.

Some considered developing relationships with families a “priority” because it facilitated communication and better care and led to “closer” relationships with residents. Many workers reported showing respect for family members, listening, and being empathetic to their concerns. For some, this strategy was about conflict avoidance, but it also contributed to the development of positive relationships and caring partnerships. One explained:

I have a good relationship with them because their transition is hard and they’re having to deal with a loved one being away from home. So, I try to respect them, and then we’ve got some that is very—they get very combative or upset with you and I just try to listen to their problem and then help them solve it.

Some workers felt that keeping family members informed “about what is going on” was essential to developing “good rapport.”

Many staff members believed they possessed special qualities that enhanced their job performance and thus influenced family attitudes and subsequent relationships. According to one worker, families “know the ones that are really here to take care of [residents] and take care of them. And they know the ones that are just here for a job . . . they confide in us.” Close relationships with residents also prompted more positive relationships with families. One worker noted, “The residents that you’re closer to, the families see that and I guess they appreciate it.”

Family factors.

Family members’ treatment of staff was pivotal. As previously discussed, the nature of interactions influenced workers’ perceptions and experiences. More positive relationships developed with family members who treated workers with respect, partnered in caregiving, and affirmed their professional identities. When family members were friendly toward care staff and took a personal interest in them, relationships tended to be closer and more satisfying.

Negative behaviors typically resulted in distant and sometimes strained relationships. For example, when asked about the influence of race, an African American care worker from an urban facility said:

We have one family, but I don’t pay them no mind … they’ll say little smart remarks, like “them colored people whatever” . . . . To me, it’s more like smile even though you don’t want to, smile and say in the back of your head that’s an ignorant person right there. And they don’t know no better and you keep on going.

As noted earlier, family support was a key factor. Good support involved care collaboration, rather than interference, which could lead to conflict. Occasionally, family members did “everything” for the resident. Such care “made the job easier” and showed that families “really care” about the resident, leading workers to “feel better” and “want to go that extra mile.” Certain family members also were active in facility life—attending events and, in some cases, volunteering at the facility. For example:

Well, the little lady that I am close to . . . she has got a sister. I’m real close to the sister, and the reason why is because the sister is real concerned, she is very helpful. We can call her anytime. She volunteers for all of our programs and everything.

Such involvement was more likely but not exclusively found in small-town and rural communities.

Facility Factors.—

A number of facility characteristics influenced staff–family interactions. Facility size was one. Although care workers in large ALFs reported personal relationships, the frequency of staff–family interactions in smaller homes (with fewer individuals occupying smaller spaces) heightened familiarity. The administrator of a 24-bed home explained, “We are smaller than the 150-bed facilities, so they [care staff] are with them [residents] all the time and then the families come in and the relationships build up with the families.” The amount and source of facility fees, alongside the facility’s philosophy regarding who is the customer (resident or family) and type of ownership, were influential. A common practice in high-fee facilities is for administrators to cater to families, particularly when they pay the bill. In such cases, family members sometimes “expect more and complain more because they pay for it.” Low-fee facilities had fewer resources and typically less family support, in part because families were themselves poor.

Certain policies and practices shaped relationships. Some facilities attempted to promote familiarity between staff and family members by having introductory meetings, making staff name tags mandatory, and including staff in social events and support groups involving families. Other practices included hosting “family nights,” encouraging participation in residents’ council meetings, and inviting family “to everything.” Some ALFs created particularly welcoming environments for families. One worker described her small rural facility as “family-like,” explaining: “The family pretty much comes when they want. They can drop in any time . . . if they come here at lunch time and they want to eat, you know, they’ll let them eat and never charge them.”

Some facilities educated families on their expected role and the importance of resident support. The administrator of a facility with high levels of resident frailty explained:

We also want the family member to know what my job is and what I can and cannot do for the resident. The more the family is educated, the more they will realize what the care staff can and cannot do. Unless there is open communication, then they don’t know.

In other facilities, however, family members were given unrealistic expectations. According to a worker in a corporately owned high-fee facility, “I guess they feel like they pay too much money and have the right for things to be done their way. When they move in here, they promise them everything, and when in reality that is not the way it is.” This disjuncture often led to staff–family conflict.

Facilities influenced relationships by dictating through policy how staff should interact with family members. Some encouraged staff to “keep it professional” and not get “personal.” In a number of homes, staff were encouraged to communicate openly with family members. According to one administrator:

If there is a disagreement in the way services are being provided, or if there is a disagreement with what we are seeing and what the families are seeing, then that is when we want to have another person involved to get our point across. We want care managers to feel free to interact and relate with families.

In other facilities, policies forbade such interaction. Compliance was enforced with threats of termination. One worker explained, “They have a policy that we can’t discuss what’s going on. We are limited on what we can say, or we get fired. Sometimes we need to speak more, but we can’t.” Although some administrators felt such restrictions avoided “mix-ups” or “problems,” most workers wanted the freedom to discuss residents’ care with families.

Some facilities had formalized ways of facilitating family appreciation of care workers. Many had employee recognition programs in which families participated in selecting awardees. As suggested earlier, others provided comment cards or boards where families could publicly recognize staff.

Gift giving was another way staff spoke of families showing appreciation. Although a few ALFs, all small, had no gift-giving limits, the majority had restrictions, such as limiting the amount or requiring equal division among staff, contribution to a common fund, or gifts only on birthdays. A few facilities banned gift giving. An administrator explained this practice, “We don’t want to set up any situation or perceived situation where a resident or family gets preferential treatment because they have given a gift to someone.” The inability to receive gifts was perceived by some staff as a barrier to relationships. One caregiver said, “The family asks to give us gifts, or take us out, but we can’t accept. I would like to be more friendly.”

Corporately-owned facilities tended to have more policies governing staff–family interactions. In all facilities, however, the administrator generally determined which policies to follow. Some made efforts to point out (to families) good things caregivers had done or to pass along family members’ compliments to staff. One administrator’s strategy was to convey family appreciation immediately and directly: “If a family member comes and tells me that a staff person did something right, I go to them right away and give them the feedback and the praise in front of their peers and in front of other residents or family members.” Some administrators were especially supportive of staff regarding family issues, viewing all sides, or admonishing rude family members.

Community Factors.—

Community size and location influenced relationships. These factors often operated together, with staff and family members from small communities in less urban settings frequently having preexisting connections outside the ALF. A small-town worker explained, “Just talking to them [families] and they know so and so, or they grew up with your parents, your mother-in-law, father-in-law . . . .” Such familiarity led to more personal relationships. Interactions often took place outside the ALF, such as in a local store. A care worker in a small town illustrated this situation, saying, “We have a lady [who] has been here for two years and she talks to her daughter about me all the time. Well, I run into her at Wal-Mart. I talked to her for an hour and a half at Wal-Mart [the other day].” This type of encounter was not evident in larger communities.

Community-level factors influenced the degree of social and economic commonality among staff and family members. For example, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity found in small rural communities in the northern part of the state led to a shared background and culture between workers and family members, which enhanced relational closeness. In contrast, in larger facilities located in more urban and diverse areas, discriminatory attitudes found in the wider community sometimes spilled over inside, resulting in tense, strained relationships between Black staff and White family members.

Discussion

In this article, we examined staff–family relationships in ALFs. Consistent with NH research, we found that relationships were perceived as both positive and negative, sometimes characterized by ambiguity, and an important part of the work environment. Most workers aspired to having relationships that offered personal and professional affirmation, which in turn was central to understanding how families affected workers’ day-to-day work experiences. We identified respect, partnerships in caring, and affirmation of professional caregiver identity as elements that give rise to global affirmation.

The identification of global affirmation as a linking mechanism between staff–family interactions and the nature of work experiences offers insight into why these relationships are of import in the care industry. As Neysmith and Aronson (1996, p. 12) point out, “caring as skilled and significant work . . . can be a source of pride and identity.” Thus, the desire for global affirmation may relate to workers’ efforts to maintain and enhance their personal and professional identities within the context of an unskilled profession that is undervalued in the labor market. Through their support and appreciation, families appear to be influential in helping workers accomplish this goal.

Ball and colleagues (2009) suggest that workers in assisted living take pride in their work, specifically the relational dimensions of caring, including their perceived importance in residents’ lives. In turn, they take pride in themselves that allows them to renegotiate/reinterpret and elevate their job status. Having desirable interactions with family members helped care workers in our study feel “good” and “proud” and maintain positive personal and professional identities that resulted in positive work experiences. Undesirable interactions had the opposite influence.

These observations resonate with Parks’ (2003, pp. 85–86) feminist commentary on the home health care industry in which she draws attention to workers’ status and treatment in the work setting, highlights the importance of “understanding selves as relational,” and argues for “a relational concept of autonomy,” all of which translates well to the assisted living industry. She underscores the importance of relationships, suggesting that rather than viewing “selves as ‘islands unto themselves,’ and processes of individuation as setting us apart from one another, relational autonomy sees our selves as developing out of the relationships in which we are enmeshed” (p. 86). In other words, all those implicated in the caring relationship are important to understanding how to improve conditions for caregivers and, in doing so, care recipients. She posits that care recipients’ selves are connected to those who care for them. Correspondingly and applied to the assisted living setting, it is apparent that care workers’ selves are tied to the nature and quality of relationships they have with residents and, as our findings indicate, residents’ family members.

We also found community, facility, and individual factors joined together to influence staff–family relationships and, to a certain extent, global affirmation. We confirmed that factors identified in NH research, such as a facility’s family orientation and family, staff, and resident attitudes and behaviors, also operate in ALFs. Our analysis documented additional influences, including the role of community factors, and highlighted connections between factors and relational outcomes. Factors such as facility size and commonality of background between staff and families cannot be changed, but several factors can be manipulated in ways that could improve staff–family relationships in ALFs and promote global affirmation.

To begin, lack of family involvement was a source of frustration and an impediment to delivering care effectively. As others have found, most workers viewed family support as especially crucial in these instances because it helped them know more about residents and offer more personalized care (R. Karner, Montgomery, Dobbs, & Wittmaier, 1998). Family support is apt to have a positive influence on care outcomes, but as care workers feel good when residents are well taken care of and have what they need, it can also lead to positive staff outcomes (see also Ball et al., 2009).

Our research indicates the need to educate families about assisted living, their expected roles, and the value of care partnerships. Facilities can promote family involvement through meetings, workshops, visiting policies, and family councils or support groups (Ball et al., 2005). They also can encourage familiarity between staff and family by taking proactive approaches to relationship development. Removing barriers that prohibit communication between staff and family members would promote the development of caring partnerships. Some facilities successfully managed to promote relationships by hosting family events that involve staff and making name tags mandatory for staff. Making information about care staff available to family members through, for example, newsletters or a bulletin board or album displayed in the facility might increase familiarity.

Families need to know how their behaviors influence care staff. Administrators can reinforce this message. Workers indicated the importance of appreciation as a dimension of affirming their professional identity. Facilities can encourage family members to express their appreciation by providing formal and informal outlets for doing so. Successful facilities’ strategies included the use of comment cards and boards, employee-of-the-month programs, and gift giving. These strategies worked to promote affirmation. Moreover, just as with families, caregivers need to consider family members’ perspectives. Most, but not all, were sensitive to families. Training should include communicating some of the challenges from the families’ perspectives.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study is not without limitations. First, we collected data exclusively in Georgia, which invites questions about the possibility of regional differences. Next, our sample did not include facilities with fewer than 16 beds. Finally, notably absent are the perspectives of family members and residents. Additional research, both qualitative and quantitative, is necessary to understand relationships in other regions and smaller settings and from all perspectives.

Despite these limitations, our findings illuminate additional paths for future research. Nursing home intervention studies demonstrate that relationships between staff and families can be improved with positive outcomes for facilities, families, residents, and staff (Pillemer et al., 2003). Although beyond the scope of this article, a recent edited volume presents a number of programs and initiatives aimed at improving family involvement in NHs (Gaugler, 2005b). Further research might consider their use in ALFs, where care partnerships are apt to take on a slightly different character owing to the reliance on family members to assist in care delivery. Our findings could be helpful in this regard.

We found that residents with dementia, including those in DCUs, often received fewer family visits. This finding is somewhat contrary to Robison and Pillemer’s (2007) finding that NH staff employed in units designed for residents with advanced dementia or special care units (SCUs) have better family relationships than those working in traditional NHs. They suggest that it is not working in an SCU per se but the quality of the relationships that make a difference. Future research would do well to compare the dynamics of staff–family relationships in both settings.

Within the context of an industry where White residents typically are being cared for by non-White, and increasingly foreign-born, care workers (Redfoot & Houser, 2005), racism in these settings also requires further attention. Berdes and Ekert (2001) explored the effects of racial and ethnic differences between staff and residents in NHs. Staff experienced racism most often from residents, but family members, coworkers, and, in some cases, supervisors were also perpetrators. Ball and colleagues (2009) found that racist behaviors influenced staff–resident relationships in ALFs; yet, very little is known about the role racism plays in the negotiation of staff–family interactions. In the present study, administrators wielded considerable influence on the culture of a home, often dictating how policy and practices were implemented. The extent to which a facility tolerates racist behaviors on the part of family members (or anyone) is largely dependent on management, which is particularly problematic if managers themselves are racist. As Berdes and Ekert (p. 124) conclude, “[M]uch work needs to be done to develop ways of recognizing and intervening in the problem” of racism in LTC.

In sum, as in other care settings, staff–family relationships are one of many factors influencing direct care workers’ experiences in ALFs. In the context of worker shortages and the demand for LTC, especially quality care, it is imperative that ALFs find ways to attract and retain workers. Improving staff–family relationships is a potential avenue for doing so. We need to further understand the role of workplace relationships in patterns of satisfaction and retention but also consider how as a society we might elevate the status of these workers and appreciate them for the roles they perform in LTC delivery. As the population continues to age, realizing this goal will become increasingly important for the well-being of workers, residents, and their family members.

Acknowledgments

The data for this article come from the study “Job Satisfaction and Retention of Direct Care Staff in Assisted Living” funded by the National Institute on Aging (1R01 AG021183; Mary M. Ball, principal investigator). A version of this article was presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, San Francisco, California, 2007. We thank Frank Whittington for his support and feedback throughout the research and writing process. We are also very grateful to all those who participated in the study.

References

- Ball MM, Lepore ML, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Sweatman M. “They are the reason I come to work”: The meaning of resident-staff relationships in assisted living. Aging Studies. 2009;23:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Coombs BL. Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ. Surviving dependence: Voices of African American elders. Amityville, NY: Baywood; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. The relationship between staffing and quality in long-term care facilities: Exploring the view of nurse aides. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2000;14:55–64. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdes C, Eckert JM. Race relations and caregiving relationships. Research on Aging. 2001;23:109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chichin ER. Home care is where the heart is: The role of interpersonal relationships in paraprofessional home care. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 1992;13:161–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D, Montgomery R. Family satisfaction with residential care provision: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2005;24:453–474. [Google Scholar]

- Foner N. The caregiving dilemma: Work in an American nursing home. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann ML, Montgomery RJ, Mailberger B, Smith AA. Family involvement in the nursing home: Family-oriented practices and staff-family relationships. Research in Nursing and Health. 1997;20:527–537. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199712)20:6<527::aid-nur7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland R. Caregivers and long-term care needs in the 21st century: Will public policy meet the challenge? 2004. Long-term Care Financing Project. Washington, DC: Georgetown University. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE. Family involvement in residential long-term care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging & Mental Health. 2005a;9:105–118. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331310245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, editor. Promoting family involvement in long-term care settings. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press; 2005b. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Ewen HH. Building relationships in residential long-term care: Determinants of staff attitudes toward family members. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2005;31:19–26. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20050901-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RL. Families in assisted living [Special issue III] Gerontologist. 2007;47:83–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J, Wexler E. The development of relationships between families and staff in long-term care facilities: Nurses’ perspectives. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2002a;21:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J, Wexler E. Exploring the relationships between families and staff caring for residents in long-term care facilities: Family members’ perspectives. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2002b;21:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes C, Rose M, Phillips C. A national study of assisted living for the frail elderly. Executive summary: Results of a national survey of facilities. Beachwood, OH: Myers Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg A, Ekman SL, Axelsson K. ‘Relatives are a resource, but…’: Registered nurses’ views and experiences of relatives of residents in nursing homes. Journal of clinical nursing. 2003;12:431–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner TX. Professional caring: Homecare workers as fictive kin. Journal of Aging Studies. 1998;12:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Karner R, Montgomery R, Dobbs D, Wittmaier C. Increasing staff satisfaction: The impact of SCUs and family involvement. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1998;24:39–44. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19980201-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica R, Johnson-LaMarche H. State residential care and assisted living policy: 2004. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neysmith SM, Aronson J. Home care workers discuss their work: The skills required to “use your common sense. Journal of Aging Studies. 1996;10:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Parks JA. No place like home? Feminist ethics and home health care. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Henderson CR, Meador R, Schultz L, Robison J, et al. A cooperative communication intervention for nursing home staff and family members of residents [Special issue II] Gerontologist. 2003;43:96–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfoot D, Houser A. We shall travel on: Quality of care, economic development, and the international migration of long-term care workers. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robison J, Curry L, Gruman C, Porter M, Henderson CR, Pillemer K. Partners in caregiving in a special care environment: Cooperative communication between staff and families on dementia units. Gerontologist. 2007;47:504–515. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison J, Pillemer K. Job satisfaction and intention to quit among nursing home nursing staff: Do special care units make a difference? Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2007;26:95. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg J, Nolan MR, Lundh U. Entering a new world: Empathic awareness as the key to positive family/staff relationships in care homes. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2002;39:507–515. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(01)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shield RR. Wary partners: Family-staff relationships in nursing homes. In: Stafford PB, editor. Gray areas: Ethnographic encounters with nursing home culture. Santa Fe, NM: School of America Research Press; 2003. pp. 203–233. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]