Abstract

Translational inhibitors such as the trichothecene mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON) and ribosomal inhibitory proteins (RIPs) induce mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)–driven chemokine and cytokine production by a mechanism known as the ribotoxic stress response (RSR). Double-stranded RNA–activated protein kinase (PKR) associates with the ribosome making it uniquely positioned to sense 28S ribosomal RNA damage and initiate the RSR. We have previously shown that PKR mediates DON-induced MAPK phosphorylation in macrophages and monocytes. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that PKR is essential for induction of interleukin (IL)-8 expression in monocytes by DON and two prototypical RIPs, ricin, and Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1). Preincubation of human monocytic U937 cells with the PKR inhibitors C16 and 2-aminopurine (2-AP) blocked DON-induced expression of IL-8 protein and mRNA. Induction of IL-8 expression was similarly impaired in U937 cells stably transfected with a dominant negative PKR plasmid (UK9M) as compared with cells transfected with control plasmid (UK9C). Nuclear factor-kappa B binding, which has been previously shown to be a requisite for DON-induced IL-8 transcription, was markedly reduced in UK9M cells as compared with UK9C cells. As observed for DON, ricin-, and Stx1–induced IL-8 expression was suppressed by the PKR inhibitors C16 and 2-AP as well as impaired in UK9M cells. Taken together, these data indicate that PKR plays a common role in IL-8 induction by DON and the two RIPs, suggesting that this kinase might be a critical factor in RSR.

Keywords: kinase, immunotoxicity, ribotoxic stress chemokine

Deoxynivalenol (DON, vomitoxin) is a fungal secondary metabolite, produced primarily by Fusarium graminearum, and classified as a trichothecene (Pestka and Smolinski, 2005). DON binds to the peptidyl transferase center of eukaryotic ribosomes and inhibits protein translation by interfering with chain elongation (Ehrlich and Daigle, 1987). DON induces gene expression and/or apoptosis mediated in a concentration-dependent fashion via activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) in monocytes, macrophages, T cells and B cells (Islam et al., 2006; Uzarski and Pestka, 2003; Yang et al., 2000) as well as in lymphoid tissues of mice following oral administration (Zhou et al., 2003a).

DON-induced MAPK activation mediates increased expression of several proinflammatory genes including COX-2, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2 and IL-8 (Chung et al., 2003a, b; Islam et al., 2006; Moon and Pestka, 2002). Aberrant upregulation of IL-8 is particularly notable because this CXC chemokine functions as a neutrophil chemoattractant, induces adherence of neutrophils to vascular endothelium and triggers extravasation into tissues (Linevsky et al., 1997). IL-8 is a biomarker of sepsis (Herzum and Renz, 2008; Lam and Ng, 2008) and elevated levels of it correlate with severity of several chronic diseases (Alzoghaibi et al., 2003; Banks et al., 2003; Georganas et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2000; Suzuki et al., 2000). The capacity of DON to aberrantly upregulate IL-8 production is therefore potentially of toxicological significance.

Both p38 and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) play important roles in IL-8 expression (Bhattacharyya et al., 2002; Grassl et al., 2003; Marie et al., 1999; Shuto et al., 2001) and, furthermore, p38 activation can be linked to NF-κB activation (Hippenstiel et al., 2000). Consistent with these findings, we recently established that p38 activation is necessary for DON-induced IL-8 expression in cloned and primary human monocytes (Islam et al., 2006) and that DON-induced IL-8 expression is also NF-κB–dependent (Gray and Pestka, 2007).

MAPK activation by trichothecenes and other translational inhibitors has been termed the “ribotoxic stress response (RSR),” a process believed to be triggered by damage to the 28S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) peptidyl transferase center (Iordanov et al., 1997; Shifrin and Anderson, 1999). Two well-known, potent inducers of the RSR are the ribosomal inhibitory proteins (RIPs) Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1), which is produced by E. coli O157:H7 (Iordanov et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2003) and ricin, which is produced by the castor bean plant (Smith et al., 2003). Stx1 and ricin are N-glycosidases that target the sarcin-ricin loop of the 28S rRNA peptidyl transferase center (Narayanan et al., 2005). Both of these RIPs are included in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Select Agents list because of their potential for use as agents of bioterrorism (Pastel et al., 2006), and are thus of considerable public health importance. Like DON, both Stx1 and ricin elicit IL-8 production in experimental animals and cell cultures (Andreoli, 1999; Gonzalez et al., 2006b; Jandhyala et al., 2008; Nakagawa et al., 2003; Thorpe et al., 1999; Yamasaki et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2001).

A critical gap remains in our understanding of the early upstream signal transduction events that mediate induction of IL-8 expression by DON and other translational inhibitors. An attractive candidate for transducing early signals is double-stranded (ds) RNA–activated protein kinase (PKR). PKR contains two dsRNA-binding domains which contribute to its activation and ability to phosphorylate other proteins (Sadler and Williams, 2007). PKR phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor-2α, which reduces protein synthesis (Galabru and Hovanessian, 1987; Hartley and Lord, 2004). PKR is also known to upregulate p38 activation and NF-κB binding (Garcia et al., 2006; Williams, 2001). Because PKR associates with the ribosome in close proximity to the peptidyl transferase center (Kumar et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 1997), it might be uniquely positioned to serve as a sensor for 28S rRNA damage. Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that PKR plays a role in DON-induced activation of p38 and other MAPKs in cloned monocytes and macrophages (Zhou et al., 2003b).

The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that PKR is essential for inducing IL-8 expression by DON, Stx1 and ricin in human U937 monocytes. The results indicate that PKR was required for induction of IL-8 by all three toxins, suggesting that this kinase plays an important role in the RSR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design.

All chemicals and reagents were from Sigma (St Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. U937 cells, isolated from the pleural effusion of an individual with diffuse histiocytic lymphoma (Sundstrom and Nilsson, 1976), were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD) at 37°C with 6% CO2. Fresh media was added as necessary to passage the cells. Cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated with DON (Sigma), Stx1 (Toxin Technology, Inc, Sarasota, FL) or ricin (Vector, Burlingame, CA) for time intervals deemed optimal in preliminary studies for determination of IL-8 protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (12 h), IL-8 mRNA by reverse transcription–PCR (6 h) or NF-κB binding (3 h). Concentrations of Stx1 and ricin were chosen based on those found in previously published studies (Ramegowda and Tesh, 1996; Rao et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2003; Uzarski and Pestka, 2003).

In some studies, different selective PKR inhibitors were used. The PKR inhibitor C16, an imidizole-oxindole compound (Jammi et al., 2003) or its negative control, an inert analog, were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to cultures at 2.5μM 45 min prior to toxin addition. The PKR inhibitor, 2-aminopurine (2-AP) (5mM in water) or vehicle control were added to cultures 1 h prior to toxin addition. The p38 inhibitor, SB203580 (Calbiochem) (2.0μM in DMSO) or vehicle control were added as cotreatments with DON. Concentrations for the three inhibitors were not cytotoxic in the MTT assay and were selected based on previously published cell culture studies (Cheung et al., 2005; DeWitte-Orr et al., 2007; Islam et al., 2008; Ito et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2003b).

Other studies employed U937 cells that were stably transfected with a constitutively expressed nonfunctional mutant form of PKR (U9KM) cells or with an empty plasmid (U9KC) as described previously (Cheung et al., 2005). U9KM and U9KC cells were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 0.5 mg/ml geneticin (Gibco BRL) and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL).

RNA isolation and reverse transcription real-time PCR.

RNaqeous kits (Ambion, Austin, TX) were used to isolate RNA from cell pellets. Briefly, cells are lysed, nucleic acids precipitated with ethanol, RNA trapped in a glass fiber filter, and the RNA eluted and stored at −80°C.

Reverse transcription real-time PCR was performed using One-Step PCR Master Mix and IL-8 Taqman Gene Expression Assay (NCBI NM 000584.2) (NCBI B2M-NM 004048.2) or the β-2 microglobulin Taqman Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Reaction conditions and PCR program followed the manufacturer's instructions using an ABI 7900HT (384 wells) at the Michigan State University's Research Technology and Support Facility. Fold change was determined using a relative quantitation method (Smolinski and Pestka, 2005).

IL-8 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

After treatments, cell cultures were centrifuged for 10 min at 300 × g and the supernatant fraction collected. OptELISA kits (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) were used for IL-8 protein measurement according to manufacturer's instructions with two modifications. First, the highest standard utilized was 1600 pg/ml, instead of 400 pg/ml. Second, to economize on reagents 50 μl of antibody dilutions and samples were used per well instead of 100 μl. All samples were read at 450 nm in a Vmax Kinetic Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA).

Nuclear protein isolation and assessment of NF-κB binding.

Nuclear proteins were isolated using the Nuclear Extraction Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Separation of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins was done by using a hypotonic buffer and detergent to break the cytoplasmic membrane, then pelleting and lysing the nuclei. Nuclear protein was quantitated with a DC Protein Quantitation Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and diluted to 2.5 μg/μl. Binding of p65 NF-κB was assessed with the TransAM NF-κB Family Flexi kit (Active Motif) using IL-8 promoter specific probe sequences as described previously (Gray and Pestka, 2007). The wild-type IL-8 probe was labeled using a Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer's instructions. Probes were duplexed by incubating 1 pmol/μl of each oligonucleotide together at 95°C for 5 min and ramping back to 4°C by decreasing 1°C/min. Nuclear protein (20 μg) was incubated with a duplex, biotin labeled IL-8 specific probe, then added to a strepavidin coated 96-well plate. After washing, wells were incubated sequentially with a primary antibody for p65 NF-κB, followed by anti-rabbit peroxidase-conjugated antibody. After substrate addition, peroxidase activity was by reading 450 nm in a Vmax Kinetic Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed with SigmaStat v 3.1 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). IL-8 protein and RNA data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls Method for pairwise comparisons unless otherwise noted. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

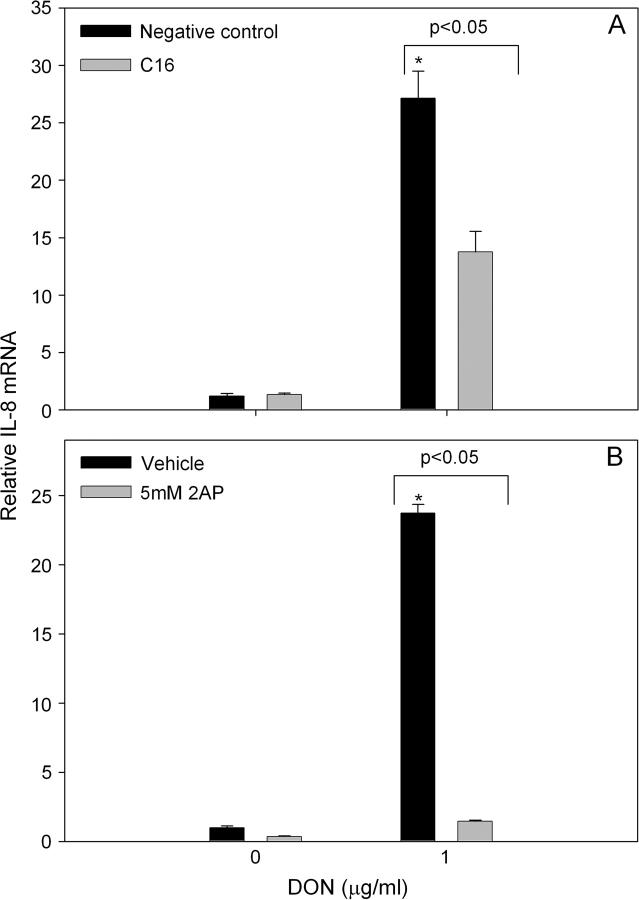

The contribution of PKR to DON-induced IL-8 mRNA expression was assessed in U937 monocytes using selective inhibitors. DON (1.0 μg/ml) markedly elevated IL-8 mRNA concentration after 6 h (Fig. 1). Pretreatment with C16 suppressed DON-induced IL-8 mRNA expression as compared with cultures treated with the negative control inhibitor (Fig. 1A). These results were confirmed with 2-AP, a second PKR inhibitor, which also significantly inhibited DON-induced IL-8 mRNA expression as compared with cultures treated with vehicle (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

PKR inhibitors significantly suppress DON-induced IL-8 mRNA expression. U937 cells were pretreated with (A) C16 inhibitor (2.5μM) or a negative control inhibitor (2.5μM) for 45 min or with (B) 5mM 2-AP or vehicle (water) for 1 h before addition of DON at the concentrations indicated. RNA was isolated 6 h after addition of DON and IL-8 mRNA assessed by real-time PCR. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) from vehicle treatment. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

Suppression of IL-8 mRNA in U937 cells by PKR inhibitors was further related to IL-8 production. DON at 0.5 and 1.0 μg/ml induced robust IL-8 protein production after 12 h (Fig. 2A). Pretreatment with the PKR inhibitor C16 inhibited DON-induced IL-8 protein production by more than 90% as compared with cultures treated with the negative control inhibitor (Fig. 2A). Pretreatment with 2-AP, also suppressed IL-8 protein production by more than 90% as compared with cultures treated with vehicle (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

PKR inhibitors significantly suppress DON-induced IL-8 protein production. U937 cells were pretreated with the (A) C16 inhibitor or (B) 2-AP as described in Figure 1 legend before addition of DON (0 or 1.0 μg/ml). Culture supernatant was collected 12 h after addition of DON and IL-8 protein was assessed by ELISA. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) from vehicle treatment. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

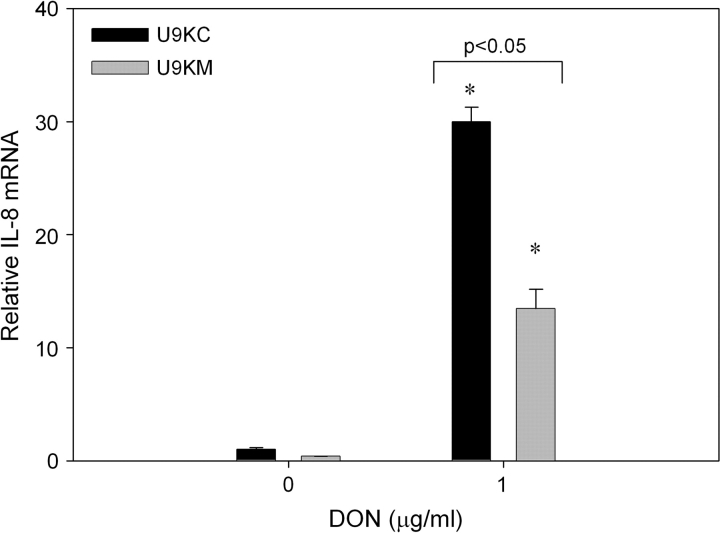

Further confirmation of the role of PKR in DON-induced IL-8 mRNA expression was obtained using U937 cells containing dominant negative PKR. Both U9KC and U9KM cells have a plasmid with a constitutive promoter stably inserted into their genome, however, the plasmid in U9KC cells is empty, whereas the plasmid in U9KM has the coding sequence for a mutant form of PKR, thus rendering the dominant form of PKR nonfunctional (Cheung et al., 2005). Both U9KC and U9KM cells exhibited increased IL-8 mRNA expression 6 h after treatment with DON. However, U9KM cells expressed significantly less IL-8 mRNA as compared with U9KC cells (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Dominant negative PKR significantly suppresses DON-induced IL-8 mRNA expression. U937 cells, stably transfected with an empty vector (U9KC) or with a constitutively expressed nonfunctional form of PKR (U9KM), were treated with 0 or 1 μg/ml DON. RNA was isolated 6 h after addition of DON and IL-8 mRNA assessed by real-time PCR. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Data are representative of two independent experiments. Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) from vehicle treatment.

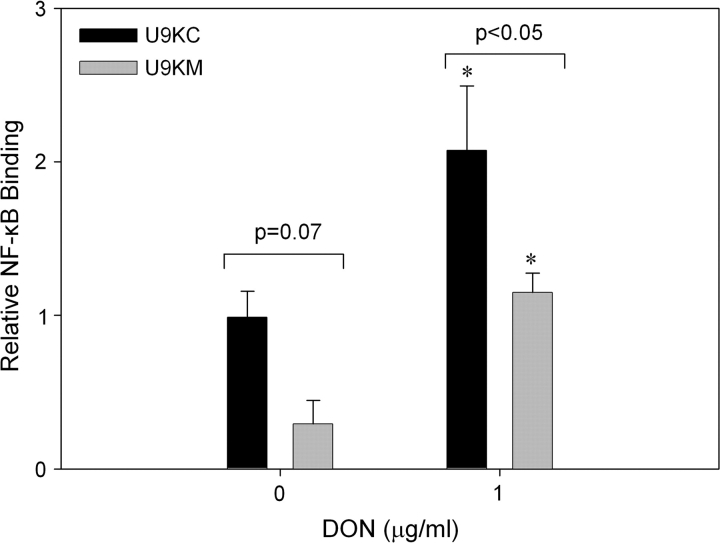

DON-induced IL-8 mRNA expression in U937 cells is mediated at the transcriptional level by NF-κB, specifically p65, but does not appear to involve mRNA stabilization (Gray and Pestka, 2007). The role of PKR in induction of p65 NF-κB binding by DON was therefore assessed using the constitutively expressing dominant negative cultures. Nuclear extracts from U9KC and U9KM cells treated with DON (1.0 μg/ml) for 3 h exhibited increased p65 NF-κB binding as compared with their corresponding vehicle controls (Fig. 4). However, extracts from DON-treated U9KM cells exhibited significantly less p65 NF-κB binding than did those from DON-treated U9KC cells. A similar trend was evident when vehicle-treated U9KM and U9KC cells were compared.

FIG. 4.

Dominant negative PKR reduces DON-induced p65 NF-κB binding. U937 cells stably transfected with an empty vector (U9KC) or with a constitutively expressed nonfunctional form of PKR (U9KM), were treated with 0 or 1 μg/ml DON for 3 h before isolation of nuclear protein and assessment of p65 NF-κB binding. Data are mean ± SEM of pooled results from two independent experiments (n = 4). Asterisk indicates significantly different from corresponding vehicle control (p < 0.05).

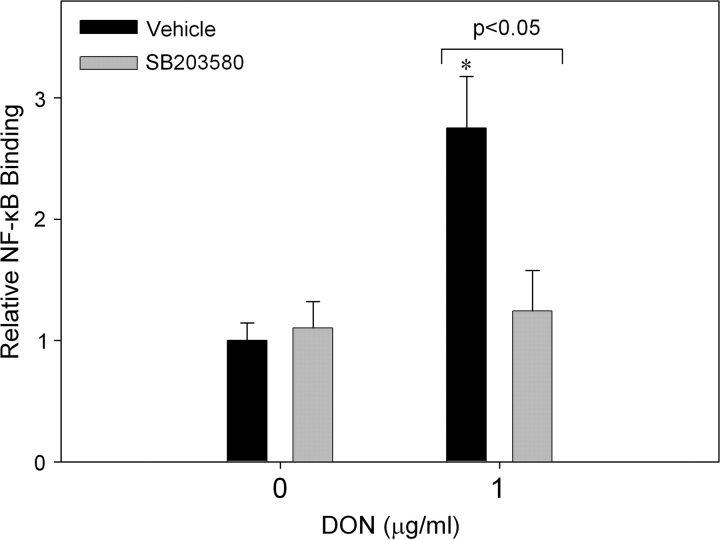

Using selective inhibitors and antisense knockdown, we have previously determined that PKR is required for DON-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation in U937 cells (Zhou et al., 2003), and further observed that p38 mediates DON-induced IL-8 protein and mRNA expression (Islam et al., 2006). Because p38 MAPK reportedly can drive NF-κB activation (Hippenstiel et al., 2000), the effects of inhibiting this kinase on DON-induced NF-κB binding were ascertained. U937 cells were incubated with and without the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 concurrently with or without DON (1 μg/ml) for 3 h prior to isolation of nuclear protein and p65 NF-κB binding measurement. Treatment with SB203580 blocked DON-induced p65 binding (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

The p38 inhibitor SB203580 significantly reduces DON-induced p65 NF-κB binding. U937 cells were treated with 0 or 2.0μM SB203580 with 0 or 1 μg/ml DON for 3 h before isolation of nuclear protein and assessment of p65 NF-κB binding. Data are mean ± SEM of pooled results from two independent experiments (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant difference from corresponding vehicle control (p < 0.05).

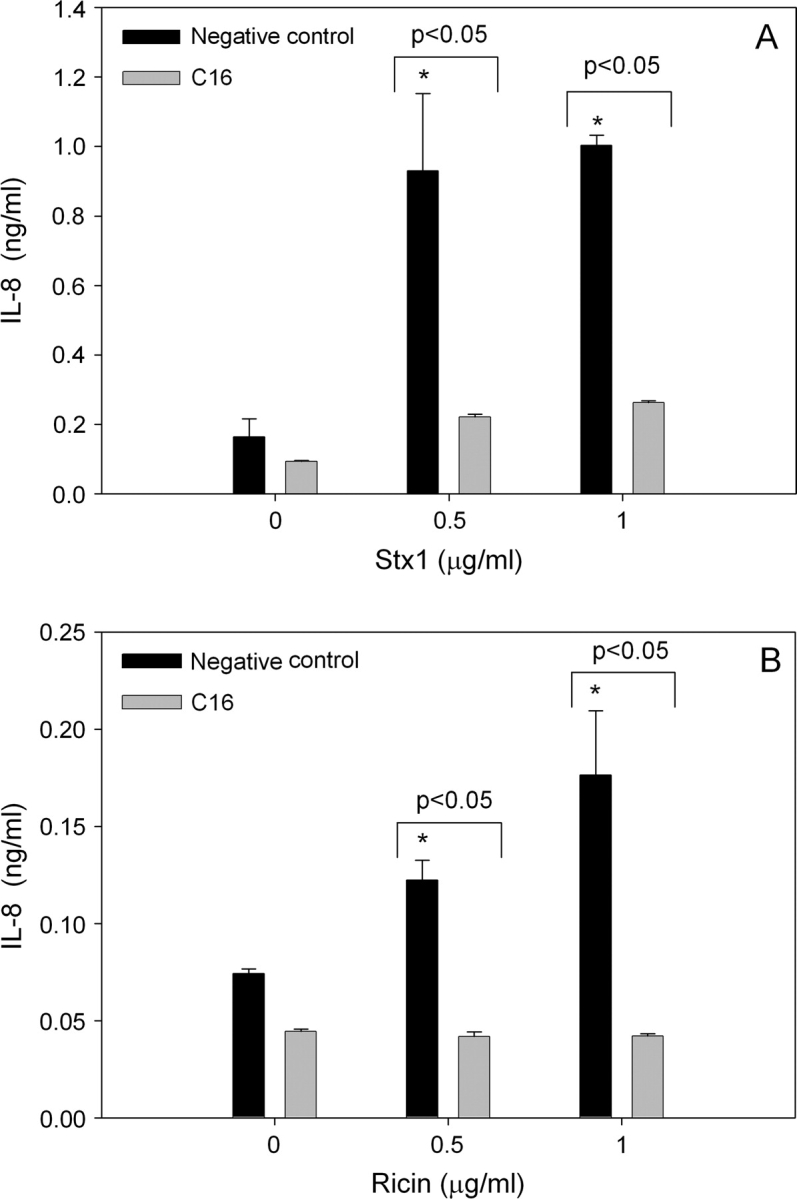

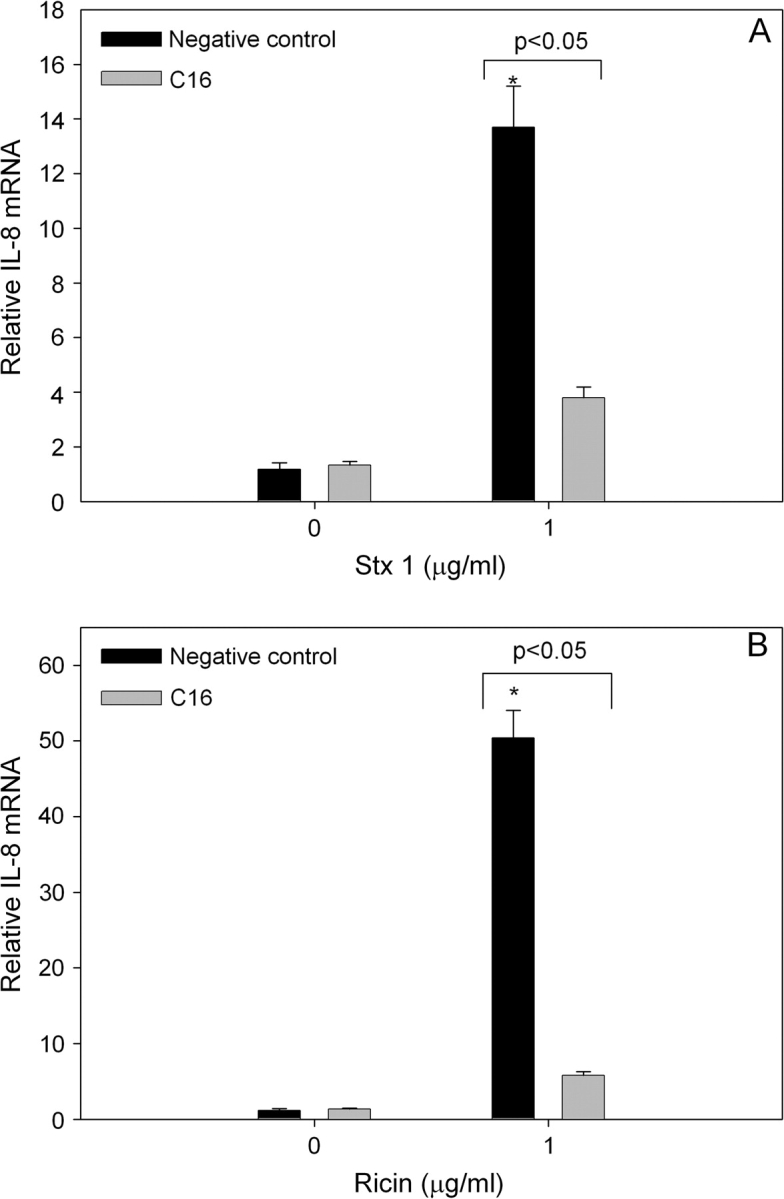

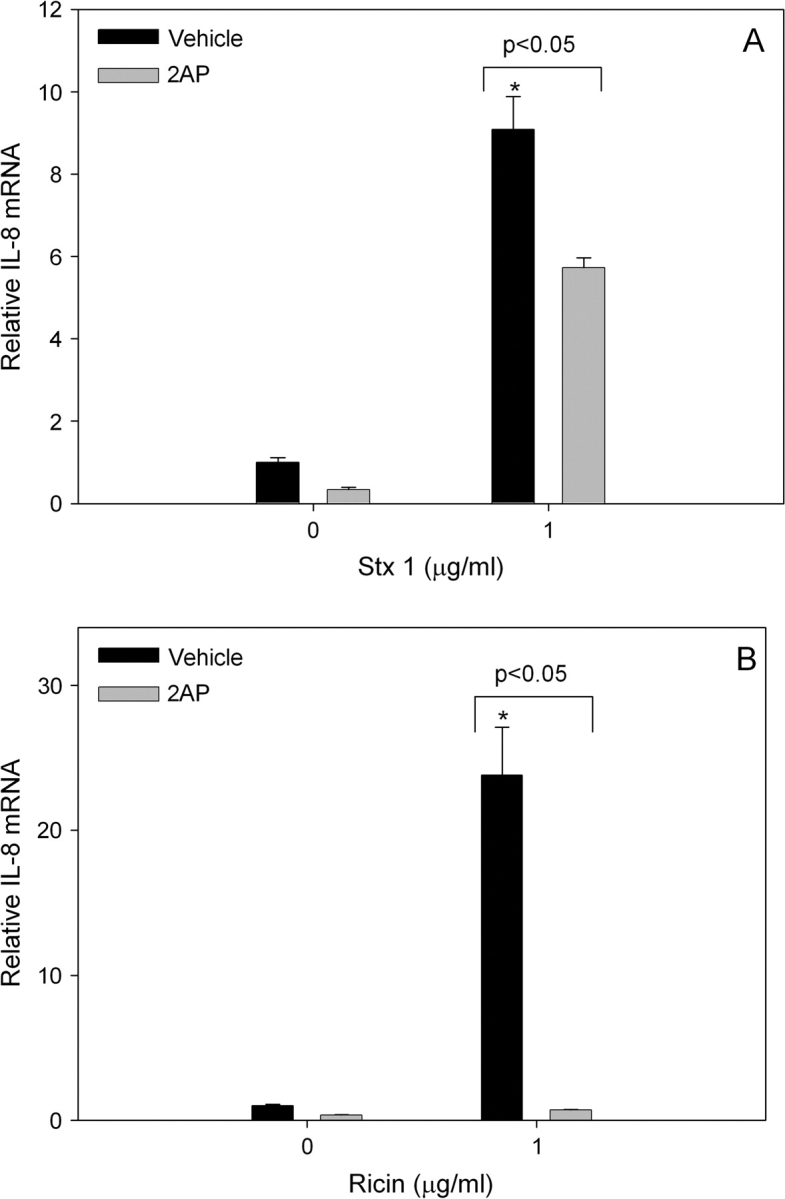

The possibility that PKR plays a similar role in mediating IL-8 induction by other ribotoxic stressors was addressed using the RIPs Stx1 and ricin in conjunction with specific inhibitors. IL-8 protein concentrations were markedly increased in U937 cultures 12 h after treatment with Stx1 at 0.5 and 1.0 μg/ml (Fig. 6A) or with ricin at 0.5 and 1.0 μg/ml (Fig. 6B). Pretreatment with the PKR inhibitor C16 reduced Stx1-induced IL-8 by approximately 80% and ricin-induced IL-8 by approximately 60%. Induction of IL-8 mRNA expression by Stx1 (1.0 μg/ml) and ricin (1.0 μg/ml) were similarly suppressed by C16 (Figs. 7A and 7B) and 2-AP (Figs. 8A and 8B).

FIG. 6.

The C16 PKR inhibitor significantly suppresses Stx1- or ricin-induced IL-8 protein production. U937 cells were pretreated with C16 inhibitor (2.5μM) or a negative control inhibitor (2.5μM) for 45 min before addition of 0, 0.5, or 1 μg/ml (A) Stx1 or (B) ricin. Culture supernatant was collected 12 h after addition of toxin and IL-8 protein was assessed by ELISA. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Asterisk indicated significantly different (p < 0.05) from vehicle control. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

FIG. 7.

The C16 PKR inhibitor significantly suppresses Stx1- or ricin-induced IL-8 mRNA expression. U937 cells were pretreated with C16 inhibitor (2.5μM) or a negative control inhibitor (2.5μM) for 45 min before addition of 0 or 1 μg/ml (A) Stx1 or (B) ricin. RNA was isolated 6 h after addition of toxin and IL-8 mRNA was assessed by real-time PCR. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) from vehicle control. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

FIG. 8.

2-AP significantly suppresses Stx1- or ricin-induced IL-8 mRNA. U937 cells were pretreated with 0 or 5mM 2-AP for 1 h before addition of 0 or 1 μg/ml (A) Stx1 or (B) ricin. RNA was isolated 6 h after addition of toxin and IL-8 mRNA assessed by real-time PCR. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) from vehicle control. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

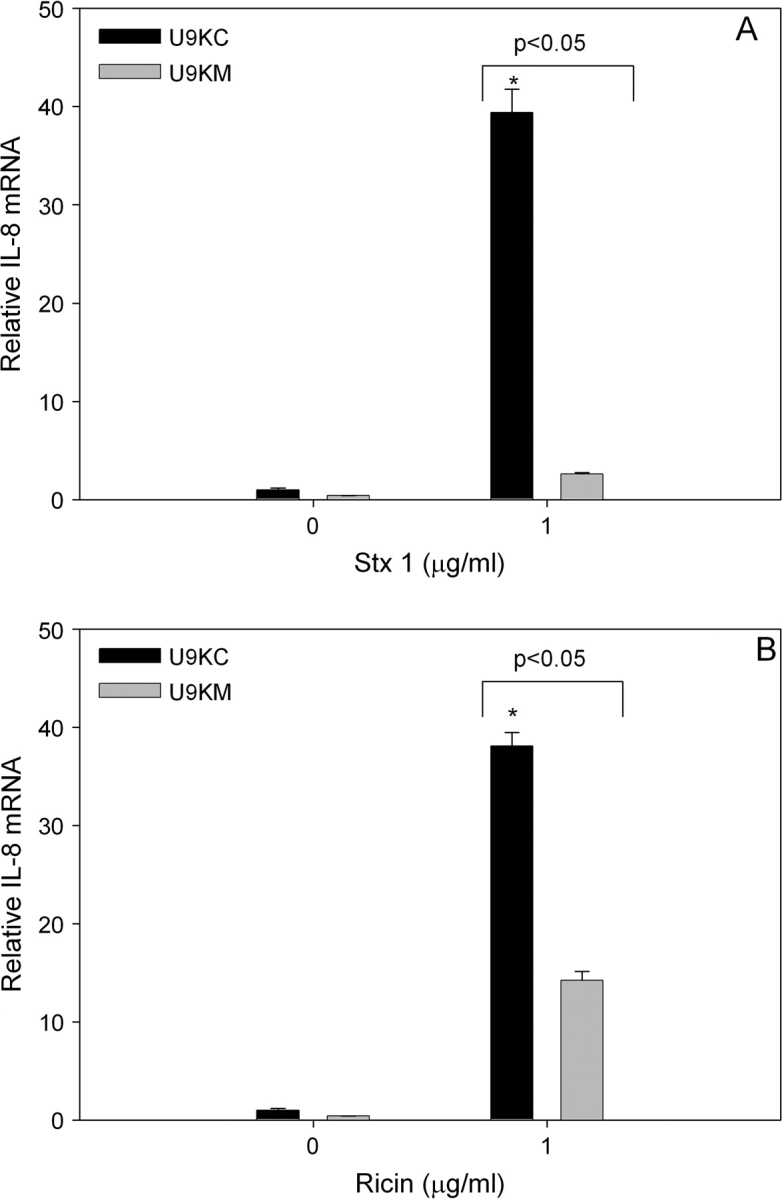

Based on the effects observed for the two chemical inhibitors, additional verification of PKR's role in RIP-induced IL-8 expression was conducted with U937 cells containing dominant nonfunctional PKR. Both Stx1 and ricin significantly induced IL-8 mRNA in U9KC cells (Figs. 9A and 9B). Upregulation of IL-8 mRNA expression was significantly lower in U9KM than U9KC cells. Thus, as with DON, Stx1- and ricin-induced IL-8 expression appeared to be mediated through PKR.

FIG. 9.

Dominant negative PKR significantly suppresses Stx1- or ricin-induced IL-8 mRNA. U937 cells stably transfected with an empty vector (U9KC) or with a constitutively expressed nonfunctional form of PKR (U9KM) were treated with 0 or 1 μg/ml (A) Stx1 or (B) ricin. RNA was isolated 6 h after addition of DON and IL-8 mRNA assessed by real-time PCR. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant difference (p < 0.05) from vehicle control. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Ribotoxins can be encountered in food, the environment, during infections and have the potential to be used as agents of bioterrorism. Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which these agents deleteriously affect human health will facilitate development of novel preventative and treatment strategies. The signal transduction events linking ribotoxin-induced 28S rRNA damage and downstream MAPK-driven events remains poorly understood. PKR is a serine/threonine kinase that is known to localize to the ribosome (Wu et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1997) and contains specific dsRNA-binding motifs which facilitate its activation (Williams, 2001). Thus, PKR is uniquely positioned to play a role as early signal transducer following damage to rRNA by a ribotoxin. In this study, we evaluated the role of PKR in a monocyte model that has been previously used by our laboratory to study mechanisms for DON-induced MAPK activation and IL-8 induction (Gray and Pestka, 2007; Islam et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2003b). The results presented here suggest PKR plays an integral role in IL-8 upregulation by DON as well as for the RIPs Stx1 and ricin.

Many studies have shown contributory roles for both NF-κB and p38 in expression of IL-8 (Bhattacharyya et al., 2002; Grassl et al., 2003; Marie et al., 1999; Shuto et al., 2001). DON-induced IL-8 expression observed in U937 monocytes is dependent on both NF-κB (Gray and Pestka, 2007) and p38 (Islam et al., 2006). Activation of NF-κB first requires that an inhibitory protein, IκB, is phosphorylated, primarily by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, and degraded in the cytoplasm before translocation of active NF-κB to the nucleus (Liang et al., 2004). PKR is known to associate and activate NIK, one potential IKK complex member (Zamanian-Daryoush et al., 2000).

PKR has been previously shown to be critical for DON-dependent activation of p38 in U937 cells (Zhou et al., 2003b). PKR is known to interact with apoptosis signaling kinase 1 (Takizawa et al., 2002) and mitogen-activated kinase 6 (Silva et al., 2004), both of which can drive p38 phosphorylation. Recently, PKR has been shown to form a functional complex with p38 (Alisi et al., 2008). Activation of p38 has also been linked to activation of NF-κB (Shuto et al., 2001). Overall, the data presented here and previously suggest that PKR plays a key role in DON-induced NF-κB upregulation either directly or via p38 and, ultimately, IL-8 expression (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

Putative mechanism for DON-induced IL-8 expression. Results presented here and previously (Gray and Pestka, 2007; Islam et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2003b) suggest that DON exposure sequentially induces PKR-dependent p38 phosphorylation and NF-κB activation both of which might drive IL-8 mRNA transcription and IL-8 protein translation.

Because DON was capable of activating the RSR and DON-induced IL-8 expression is reliant on PKR, it was of interest to determine whether other ribotoxins, such as Stx1 and ricin, require PKR for IL-8 gene induction. Previous studies have shown that Stx1- and ricin-induced IL-8 protein is p38-dependent in HCT-8 human epithelial cells (Thorpe et al., 1999) and 28SC human monocytes (Gonzalez et al., 2006a), respectively. PKR activation might represent a common point in the RSR for these three toxins. Future studies should clarify whether IL-8 expression is similarly affected in other cell lines and if NF-κB, like p38, is also involved in Stx1- and ricin-induced IL-8 expression in U937 cells.

Ribotoxic agents might alter 28S rRNA tertiary structure sufficiently for them to bind and activate ribosomal-bound PKR, driving NF-κB activation directly or indirectly via p38 activation. Ricin and Stx1 are known to have N-glycosidase activity and to damage the sarcin/ricin loop in the peptidyl transferase center of 28S rRNA. Damage to this stem loop might facilitate its binding to one or both dsRNA-binding domains of PKR thereby causing PKR's activation. The mechanism by which DON and other chemicals lacking N-glycosidase activity might activate PKR is less apparent. One possibility is that an altered tertiary structure resulting from DON binding to the peptidyl transferase area might unmask sufficient ds rRNA from the ribosome to activate PKR. An alternative possibility is that DON binding renders 28S rRNA accessible to cleavage by endogenous nucleases, thus unveiling a portion of dsRNA sufficient to activate PKR. Consistent with these possibilities, we have recently demonstrated that DON induces cleavage of the central loop of 28s domain v of peptididyl transferase (Li and Pestka, 2008). An alternative mechanism for PKR activation might involve the activation of TLR (Cabanski et al., 2008) by agonists (e.g. dsRNA, chromatin, lipids) released by necrotic cells. Further investigation of this possibility should be considered.

Taken together, these data indicate that PKR plays a common role in IL-8 induction by DON and the two RIPs suggesting that this kinase might be a critical factor in RSR. PKR might be an attractive target for prevention or treatment of trichothecene- or ricin- associated toxicoses as well as for hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with Stx-producing bacteria such as E. coli O17:H7. A clearer understanding of the signal transduction mechanisms is needed. It further needs to be determined whether PKR is similarly associated with other toxicity biomarkers and pathologic sequelae associated with ribotoxin exposure.

FUNDING

Public Health Service Grants (ES03358 and DK58833) to J.J.P.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Rosner for assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

- Alisi A, Spaziani A, Anticoli S, Ghidinelli M, Balsano C. PKR is a novel functional direct player that coordinates skeletal muscle differentiation via p38MAPK/AKT pathways. Cell Signal. 2008;20:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzoghaibi MA, Walsh SW, Willey A, Fowler AAB, Graham MF. Linoleic acid, but not oleic acid, upregulates the production of interleukin-8 by human intestinal smooth muscle cells isolated from patients with Crohn's disease. Clin. Nutr. 2003;22:529–535. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoli SP. The pathophysiology of the hemolytic uremic syndrome. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 1999;8:459–464. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks C, Bateman A, Payne R, Johnson P, Sheron N. Chemokine expression in IBD. Mucosal chemokine expression is unselectively increased in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. J. Pathol. 2003;199:28–35. doi: 10.1002/path.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A, Pathak S, Datta S, Chattopadhyay S, Basu J, Kundu M. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-kappaB regulate Helicobacter pylori-mediated interleukin-8 release from macrophages. Biochem. J. 2002;368(Pt 1):121–129. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanski M, Steinmuller M, Marsh LM, Surdziel E, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J. PKR regulates TLR2/TLR4-dependent signaling in murine alveolar macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008;38:26–31. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0010OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung BK, Lee DC, Li JC, Lau YL, Lau AS. A role for double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR in Mycobacterium-induced cytokine expression. J. Immunol. 2005;175:7218–7225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YJ, Yang GH, Islam Z, Pestka JJ. Up-regulation of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and complement 3A receptor by the trichothecenes deoxynivalenol and satratoxin G. Toxicology. 2003a;186:51–65. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YJ, Zhou HR, Pestka JJ. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional roles for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in upregulation of TNF-alpha expression by deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003b;193:188–201. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitte-Orr SJ, Hsu HCH, Bols NC. Induction of homotypic aggregation in the rainbow trout macrophage-like cell line, RTS11. Fish Shell Fish Immunol. 2007;22:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KC, Daigle KW. Protein synthesis inhibition by 8-oxo-12,13-epoxytrichothecenes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;923:206–213. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(87)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Gil J, Ventoso I, Guerra S, Domingo E, Rivas C, Esteban M. Impact of protein kinase PKR in cell biology: From antiviral to antiproliferative action. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006;70:1032–1060. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00027-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georganas C, Liu H, Perlman H, Hoffmann A, Thimmapaya B, Pope RM. Regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts: The dominant role for NF-kappa B but not C/EBP beta or c-Jun. J. Immunol. 2000;165:7199–7206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez TV, Farrant SA, Mantis NJ. Ricin induces IL-8 secretion from human monocyte/macrophages by activating the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2006a;43:1920–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez TV, Farrant SA, Mantis NJ. Ricin induces IL-8 secretion from human monocyte/macrophages by activating the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2006b;43:1920–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassl GA, Kracht M, Wiedemann A, Hoffmann E, Aepfelbacher M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Bohn E, Autenrieth IB. Activation of NF-kappaB and IL-8 by Yersinia enterocolitica invasin protein is conferred by engagement of Rac1 and MAP kinase cascades. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:957–971. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JS, Pestka JJ. Transcriptional regulation of deoxynivalenol-induced IL-8 expression in human monocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;99:502–511. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzum I, Renz H. Inflammatory markers in SIRS, sepsis and septic shock. Cum. Med. Chem. 2008;15:581–587. doi: 10.2174/092986708783769704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippenstiel S, Soeth S, Kellas B, Fuhrmann O, Seybold J, Krull M, Eichel-Streiber C, Goebeler M, Ludwig S, Suttorp N. Rho proteins and the p38-MAPK pathway are important mediators for LPS-induced interleukin-8 expression in human endothelial cells. Blood. 2000;95:3044–3051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanov MS, Pribnow D, Magun JL, Dinh TH, Pearson JA, Chen SL, Magun BE. Ribotoxic stress response: Activation of the stress-activated protein kinase JNK1 by inhibitors of the peptidyl transferase reaction and by sequence-specific RNA damage to the alpha-sarcin/ricin loop in the 28S rRNA. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997;17:3373–3381. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z, Gray JS, Pestka JJ. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates IL-8 induction by the ribotoxin deoxynivalenol in human monocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006;213:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z, Hegg CC, Bae HK, Pestka JJ. Satratoxin G-induced apoptosis in PC-12 neuronal cells is mediated by PKR and caspase-independent. Toxicol. Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn110. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Onuki R, Bando Y, Tohyama M, Sugiyama Y. Phosphorylated PKR contributes to the induction of GRP94 under ER stress. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2007;360:615–620. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jammi NV, Whitby LR, Beal PA. Small molecule inhibitors of the RNA-dependent protein kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;308:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandhyala DM, Ahluwalia A, Obrig T, Thorpe CM. ZAK: A MAP3Kinase that transduces Shiga toxin- and ricin-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1468–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar KU, Srivastava SP, Kaufman RJ. Double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) is negatively regulated by 60S ribosomal subunit protein L18. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19(2):1116–1125. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HS, Ng PC. Biochemical markers of neonatal sepsis. Pathology. 2008;40:141–148. doi: 10.1080/00313020701813735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Pestka JJ. Comparative induction of 28S ribosomal RNA cleavage by ricin and the trichothecenes deoxynivalenol and T-2 toxin in the macrophage. Toxicol. Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn111. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Zhou Y, Shen P. NF-kappaB and its regulation on the immune system. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2004;1:343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linevsky JK, Pothoulakis C, Keates S, Warny M, Keates AC, Lamont JT, Kelly CP. IL-8 release and neutrophil activation by Clostridium difficile toxin-exposed human monocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273(6 Pt 1):1333–1340. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.6.G1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, O'Connell M, Johnson K, Pritzker K, Mackman N, Terkeltaub R. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and activation of activator protein 1 and nuclear factor kappaB transcription factors play central roles in interleukin-8 expression stimulated by monosodium urate monohydrate and calcium pyrophosphate crystals in monocytic cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1145–1155. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1145::AID-ANR25>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie C, Roman-Roman S, Rawadi G. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in interleukin-8 production by human monocytes and polymorphonuclear cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide or Mycoplasma fermentans membrane lipoproteins. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:688–693. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.688-693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon Y, Pestka JJ. Vomitoxin-induced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in macrophages mediated by activation of ERK and p38 but not JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases. Toxicol. Sci. 2002;69:373–382. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/69.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Kojio S, Taneike I, Iwakura N, Tamura Y, Kushiya K, Gondaira F, Yamamoto T. Inhibitory action of telithromycin against Shiga toxin and endotoxin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;310:1194–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan S, Surendranath K, Bora N, Surolia A, Karande AA. Ribosome inactivating proteins and apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1324–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastel RH, Demmin G, Severson G, Torres-Cruz R, Trevino J, Kelly J, Arrison J, Christman J. Clinical laboratories, the select agent program, and biological surety (biosurety) Clin. Lab. Med. 2006;26:299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.03.004. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka JJ, Smolinski AT. Deoxynivalenol: Toxicology and potential effects on humans. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2005;8:39–69. doi: 10.1080/10937400590889458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramegowda B, Tesh VL. Differentiation-associated toxin receptor modulation, cytokine production, and sensitivity to Shiga-like toxins in human monocytes and monocytic cell lines. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:1173–1180. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1173-1180.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PV, Jayaraj R, Bhaskar AS, Kumar O, Bhattacharya R, Saxena P, Dash PK, Vijayaraghavan R. Mechanism of ricin-induced apoptosis in human cervical cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;69:855–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler AJ, Williams BR. Structure and function of the protein kinase R. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;316:253–292. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifrin VI, Anderson P. Trichothecene mycotoxins trigger a ribotoxic stress response that activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and induces apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13985–13992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuto T, Xu H, Wang B, Han J, Kai H, Gu XX, Murphy TF, Lim DJ, Li JD. Activation of NF-kappa B by nontypeable Hemophilus influenzae is mediated by toll-like receptor 2-TAK1-dependent NIK-IKK alpha/beta-I kappa B alpha and MKK3/6-p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways in epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:8774–8779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151236098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AM, Whitmore M, Xu Z, Jiang Z, Li X, Williams BR. Protein kinase R (PKR) interacts with and activates mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 (MKK6) in response to double-stranded RNA stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37670–37676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WE, Kane AV, Campbell ST, Acheson DW, Cochran BH, Thorpe CM. Shiga toxin 1 triggers a ribotoxic stress response leading to p38 and JNK activation and induction of apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:1497–1504. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1497-1504.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolinski AT, Pestka JJ. Comparative effects of the herbal constituent parthenolide (Feverfew) on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory gene expression in murine spleen and liver. J. Inflamm. (Lond.) 2005;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom C, Nilsson K. Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U-937) Int. J. Cancer. 1976;17:565–577. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Tetsuka T, Yoshida S, Watanabe N, Kobayashi M, Matsui N, Okamoto T. The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in IL-6 and IL-8 production from the TNF-alpha- or IL-1beta-stimulated rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 2000;465:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01717-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa T, Tatematsu C, Nakanishi Y. Double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase interacts with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Implications for apoptosis signaling pathways. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:6126–6132. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe CM, Hurley BP, Lincicome LL, Jacewicz MS, Keusch GT, Acheson DW. Shiga toxins stimulate secretion of interleukin-8 from intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:5985–5993. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5985-5993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzarski RL, Pestka JJ. Comparative susceptibility of B cells with different lineages to cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction by translational inhibitors. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2003;66:2105–2118. doi: 10.1080/15287390390211315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BR. Signal integration via PKR. Sci. STKE. 2001;2001:RE2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.89.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Kumar KU, Kaufman RJ. Identification and requirement of three ribosome binding domains in dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) Biochemistry. 1998;37:13816–13826. doi: 10.1021/bi981472h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki C, Nishikawa K, Zeng XT, Katayama Y, Natori Y, Komatsu N, Oda T, Natori Y. Induction of cytokines by toxins that have an identical RNA N-glycosidase activity: Shiga toxin, ricin, and modeccin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1671:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GH, Jarvis BB, Chung YJ, Pestka JJ. Apoptosis induction by the satratoxins and other trichothecene mycotoxins: Relationship to ERK, p38 MAPK, and SAPK/JNK activation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2000;164:149–160. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanian-Daryoush M, Mogensen TH, DiDonato JA, Williams BR. NF-kappaB activation by double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) is mediated through NF-kappaB-inducing kinase and IkappaB kinase. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:1278–1290. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1278-1290.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HM, Ou ZL, Gondaira F, Ohmura M, Kojio S, Yamamoto T. Protective effect of anisodamine against Shiga toxin-1: Inhibition of cytokine production and increase in the survival of mice. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2001;137:93–100. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2001.112507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HR, Islam Z, Pestka JJ. Rapid, sequential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and transcription factors precedes proinflammatory cytokine mRNA expression in spleens of mice exposed to the trichothecene vomitoxin. Toxicol. Sci. 2003a;72:130–142. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HR, Lau AS, Pestka JJ. Role of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase R (PKR) in deoxynivalenol-induced ribotoxic stress response. Toxicol. Sci. 2003b;74:335–344. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Romano PR, Wek RC. Ribosome targeting of PKR is mediated by two double-stranded RNA-binding domains and facilitates in vivo phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14434–14441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]