Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine the mechanism by which iron chelation affects the trophozoite survival of Entamoeba histolytica. Fe2+ is a cofactor for E. histolytica alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (EhADH2), an essential bifunctional enzyme [alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH)] in the glycolytic pathway of E. histolytica.

Methods

We tested the effects of iron depletion on trophozoite growth, the kinetics of iron binding to EhADH2, and the activities of ADH and ALDH.

Results

Growth of E. histolytica trophozoites, and ADH and ALDH enzymatic activities were directly inhibited by iron chelation. Kinetics of iron binding to EhADH2 reveals the differential iron affinity of ADH (higher) and ALDH (lower).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that iron chelation interrupts the completion of the fermentative pathway of E. histolytica by removing the metal cofactor indispensable for the structural and functional stability of EhADH2, thus affecting trophozoite survival. We propose that iron-starvation-based strategies could be used to treat amoebiasis.

Keywords: AdhE, enzyme inhibition, E. histolytica

Introduction

Entamoeba histolytica infects 50 million people yearly causing 100000 fatalities worldwide.1 E. histolytica’s cysts are ingested in contaminated food or water; trophozoites colonize the host’s large intestine causing disentery.2 Amoebiasis is treated with metronidazole; however, its usefulness is limited by high toxicity,2 which prompts the search for alternative drugs.

E. histolytica lacks mitochondria and obtains energy by fermenting glucose. The last stages of this pathway convert acetyl-CoA into ethanol by the enzymatic activities of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH).3 These functions are fused in E. histolytica alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (EhADH2), which is essential for the survival of E. histolytica.3 AdhE, a homologous Escherichia coli enzyme, is required for bacterial fermentative growth. Episomal expression of ehadh2 gene in E. coli complements an adhE knock-out mutation, providing a system for inhibitor identification.3,4 Site-directed mutagenesis of conserved histidines at the iron-binding domain of EhADH2 inactivates ADH and ALDH, thus rendering the mutant proteins unable to rescue anaerobic growth of E. coli SHH31(ΔadhE).3 Although our previous analyses suggest that iron is important for amoebic growth and enzymatic activities,3 the physiological role of iron in amoebic growth or EhADH2 function had not been elucidated. Studies have emphasized the importance of iron in pathogenic diseases and suggested iron chelation as chemotherapy, based on mammalian immune responses that sequester iron as the first line of defense.5 This study shows that iron affects ADH and ALDH enzymatic activities and trophozoite survival. We propose that iron starvation could be further explored as treatment for amoebiasis.

Materials and methods

E. histolytica strain/growth conditions

E. histolytica strain HM1:1MSS trophozoites were cultured under axenic conditions as described previously.3 Initial inoculations of 5×103 trophozoites/tube were grown for 48, 72 and 96 h and counted using a haemocytometer.

Metal/chelation effects on E. histolytica’s trophozoite growth

Amoebic trophozoites (5×103) were grown for 48, 72 and 96 h in TYI-S-33 alone or with 30 µM ferrous sulphate, 50 µM zinc sulphate, 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline or a combination of 30 µM ferrous sulphate+30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline. To measure the reversal of the chelators’ inhibitory effect on growth of E. histolytica, amoebic trophozoites were grown with 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline for 7 h, then exposed to 30 µM ferrous sulphate, 30 µM ferrous sulphate+30 µM zinc sulphate+30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline or 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline, or left in TYI medium alone (control) for 7, 24 and 40 h, and counted.

Assessment of EhADH2 ADH and ALDH activities

Bacterial cells were processed as described elsewhere.3,4 Bacterial lysates were used to measure NAD+-dependent ALDH and ADH activities. ALDH activity was assayed spectrophotometrically by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm, following the oxidation of NADH to NAD using acetyl-CoA as a substrate.3,4 ADH activity was measured similarly, by substituting acetaldehyde for acetyl-CoA as a substrate.3,4 One unit of enzyme activity is defined as that which consumed 1 mmol of NADH or NAD+/min. Activity values were averaged from three independent experiments. All samples were confirmed by SDS–PAGE and western blot analyses.3

Effect of metal cofactors on EhADH2 catalytic activity

Fe2+ content of bacterial lysates was determined colorimetrically using 1,10-phenanthroline as an indicator with an extinction coefficient of 31.5 mM/cm at 510 nm.6 EhADH2 was added to an excess of 1.5 mM (3-fold) 1,10-phenanthroline in 100 mM Trizma, pH 7.5. The 1,10-phenanthroline Fe2+ complexes were removed by dialysis against 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5. ADH and ALDH activities were measured with no ferrous sulphate, 30 µM ferrous sulphate, 50 µM zinc sulphate, 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline or a combination of 30 µM ferrous sulphate+30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline. All assays were repeated in triplicate.

Fe2+ affinity and maximum rate

As iron is not strictly a substrate, we use the term ‘binding affinity constant’ instead of Km. It is inferred that a lower binding affinity constant suggests stronger affinity for iron. The apparent Michaelis–Menten constant for iron binding and the maximum rate of reaction were determined as follows: Fe2+ was removed from partially purified EhADH2.6 The concentration of Fe2+ present in the standard activity assay buffer was varied between 10 and 500 µM, and the initial rate of reaction was measured. Constant values were calculated.

Results

Iron effects on EhADH2 expression and enzymatic activities

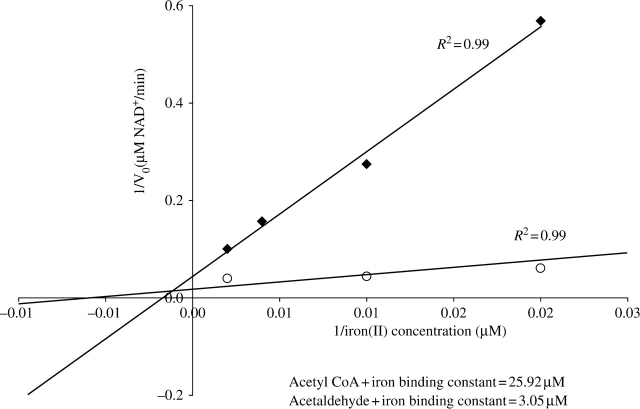

ADH and ALDH activities were enhanced by iron and inhibited by zinc or phenanthroline (Table 1). Iron in combination with phenanthroline or zinc ‘rescued’ enzymatic activities to levels similar to ones with iron alone (Table 1). SDS–PAGE showed that the effect of iron was not due to altered EhADH2 expression levels (data not shown). The affinity of EhADH2 for iron+acetaldehyde (lower binding constant=3.05 µM) was 8.5 times stronger than for iron+acetyl-CoA (25.9 µM) (Figure 1). Vmax values were calculated as the maximum rate obtainable by Fe2+ saturation in the presence of 0.2 mM acetyl-CoA or 0.5 mM acetaldehyde and 0.2 mM NADH (data not shown).

Table 1.

EhADH2 enzymatic activities are rescued by adding iron

| Metal/chelator additives | ADH (U/mg) | ALDH (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| M9 medium only | 1.31 ± 0.52 | 0.41 ± 0.19 |

| 30 µM Fe2+ | 27.88 ± 2.40 | 7.67 ± 1.19 |

| 50 µM Zn2+ | 0.23 ± 0.17 | −0.03 ± 0.3 |

| 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline | 0.71 ± 0.46 | −0.15 ± 0.8 |

| 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline+30 µM Fe2+ | 28.83 ± 1.14 | 9.21 ± 1.24 |

| 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline+30 µM Fe2++50 µM Zn2+ | 22.67 ± 2.51 | 8.56 ± 0.39 |

NAD-dependent ADH and ALDH activities were measured from partially purified bacterial lysates of E. coli SHH31 expressing wild-type recombinant EhADH2 enzyme to which indicated metals, chelator or combined additives were added.

Figure 1.

Iron-binding constants. Double reciprocal plot displaying initial rate of NADH-dependent acetyl-CoA and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase reaction as a function of Fe2+ concentration. Fe2+ was removed from partially purified EhADH2 with phenanthroline. The concentration of Fe2+ present in the standard activity assay buffer was then varied between 10 and 500 µM, and the initial rate of reaction was measured. Lineweaver–Burk plots were constructed and constants were calculated. Acetyl-CoA+Fe2+, filled diamonds; acetaldehyde+Fe2+, open circles.

Physiological effect of iron on E. histolytica trophozoite growth

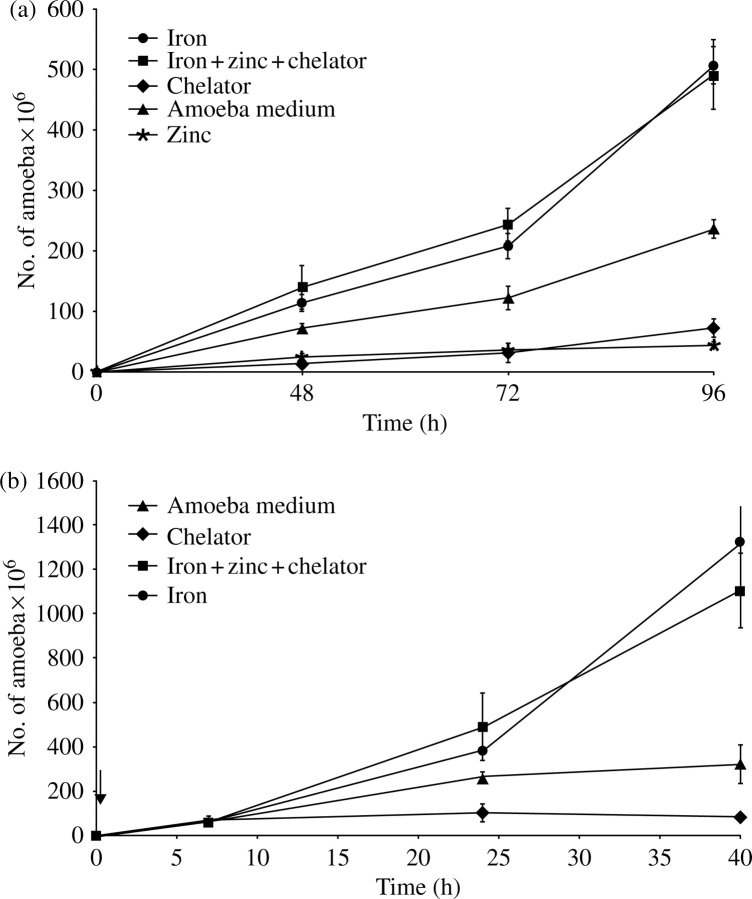

As shown in Figure 2(a), zinc and phenanthroline reduced trophozoite growth 1.5-fold compared with medium alone, whereas iron enhanced trophozoite growth 2.5-fold. Iron counteracted the inhibitory effects of phenanthroline and zinc when added together (Figure 2a). Iron starvation by phenanthroline was reversed by iron even after several hours of growth in the presence of chelator (Figure 2b). Initially, the effects of iron starvation on E. colipEhADH2 growth were tested. Iron chelation inhibited the EhADH2-expressing E. coli; supplemental iron was able to reverse phenanthroline/zinc inhibition (data not shown).

Figure 2.

(a) Inhibition of trophozoite growth by iron starvation. An initial 5×103 HM1:1MSS E. histolytica trophozoites were inoculated per tube with TYI medium alone (filled triangles), 30 µM ferrous sulphate (filled circles), 1,10-phenanthroline (filled diamonds), 50 µM zinc sulphate (asterisks) or 30 µM ferrous sulphate+50 µM zinc sulphate+1,10-phenanthroline (filled squares), and counted at 48, 72 and 96 h. (b) Chelator-dependent inhibition is reversed by iron saturation. An initial 5×103 HM1:1MSS E. histolytica trophozoites were inoculated per tube of TYI medium with 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline for 7 h. After this initial exposure to the chelator, trophozoites were exposed to 30 µM ferrous sulphate (filled circles), 30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline (filled diamonds) or 30 µM ferrous sulphate+50 µM zinc sulphate+30 µM 1,10-phenanthroline (filled squares), or left in TYI medium alone (filled triangles), and counted at 7, 24 and 40 h. The time when second additions were supplemented (after the 7 h) is indicated by an arrow.

Discussion

Our study shows that EhADH2 requires Fe2+ and is inhibited by phenanthroline/zinc (Table 1 and Figure 1). Zinc, although a divalent cation, is unable to substitute for Fe2+. EhADH2 activities can be ‘rescued’ in the presence of chelator by adding saturating Fe2+. The increase in catalytic activity in the Fe2+–chelator combination (Table 1) can be explained by this saturation. Fe2+ forms a complex with phenanthroline in a ratio of 1:3. When 30 µM Fe2+ and 30 µM phenanthroline were added, 20 µM Fe2+ remained in solution, increasing both activities. The apparent Michaelis–Menten constant for iron binding in the presence of acetaldehyde and acetyl-CoA is seen in Figure 1. A lower apparent Michaelis–Menten constant for iron (3.1 µM) with acetaldehyde confirms the importance of Fe2+ in E. histolytica’s conversion of acetaldehyde into ethanol. However, we also detected an apparent Michaelis–Menten constant for iron in the presence of acetyl-CoA (26 µM), which suggests that the ALDH activity requires an intact N-terminus and C-terminus (Table 1, Figure 1 and site-directed mutagenesis3). A recent study showed that E. coli SHH31, transformed with the N-terminal ALDH domain, retains 30% of ALDH enzymatic activity compared with the wild-type EhADH2.7 Based on our findings, we conclude that EhADH2 could have diverged structurally/functionally from the ancestral enzyme, as ADH and ALDH depend on iron binding for activity. Alternatively, an additional iron-binding site (and more than one iron) could be involved in the reaction as the Km for NADH is similar for acetaldehyde and acetyl-CoA.3

Iron increased E. histolytica trophozoite growth (Figure 2a). Growth inhibition of amoebic trophozoites by phenanthroline/zinc was countered by supplementary iron (Figure 2a). Although iron-containing superoxide dismutase (Fe2+SOD) is probably the main enzyme for detoxification of reactive oxygen intermediates,2 scavenging iron might change EhADH2 conformation and delay/prevent oxygen inactivation (Figure 2b). We delayed ADH/ALDH oxygen damage by lysing the cells with phenanthroline, thus restoring activity by adding iron prior to the assay (data not shown). E. coli’s AdhE is inactivated by hydrogen peroxide due to a metal-catalysed oxidation reaction.8 AdhE seems to act as an H2O2 scavenger in E. coli cells delaying death.8 Inactivation of iron transcriptional regulator RitR in Streptococcus pneumoniae decreases expression levels of adhE mRNA and increases susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide during exponential growth.9 The role of AdhE homologues might be to prevent DNA damage and protect pathogens from oxidative stress.

Our work implies that sequestering iron for the activities of EhADH2 (Table 1 and Figure 1) could be used to control amoebic infection. Previous studies have shown associations between amoebic infection and iron levels in humans: milk-drinking Maasai have less amoebic infections than consumers of a mixed diet (milk and blood), suggesting that low-iron-content foods could provide some resistance to amoebiasis.10 Higher incidence of amoebic liver abscess in alcoholic patients has been correlated with increased hepatic iron content.11 Interestingly, immune responses to pathogens in mammals rely on iron sequestration.5

Recent studies have linked the iron scavenging role of lactoferrin/lactoferricin to trophozoite death in vitro,12 implying that controlled iron depletion could be used to kill amoeba. Researchers have speculated that the antiamoebic effectiveness of iodo-hydroxyquinolines relies on its iron-binding properties.13 Our results demonstrate that iron chelation interrupts the completion of the fermentative pathway of E. histolytica by removing the metal cofactor indispensable for the structural and functional stability of EhADH2. In vivo mammal experimentation shall be pursued to establish the appropriate use of iron chelation against amoebiasis.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH-NCRR grant # 2 P20 RR16457-04.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shannon Arnold for technical assistance. The E. histolytica HM1:1MSS strain was provided by Sam Stanley and Lynne Foster at Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA. We are thankful to Dan Eichinger and David Clark for helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Stanley SL., Jr Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali V, Nozaki T. Current therapeutics, their problems, and sulfur-containing-amino-acid metabolism as a novel target against infections by ‘amitochondriate’ protozoan parasites. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:164–87. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espinosa A, Yan L, Zhang ZL, et al. The bifunctional Entamoeba histolytica alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (EhADH2) protein is necessary for amoebic growth and survival and requires an intact C-terminal domain for both alcohol dehydrogenase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20136–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101349200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espinosa A, Clark D, Stanley SL., Jr Entamoeba histolytica alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (EhADH2) as a target for anti-amoebic agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:56–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullen JJ, Rogers HJ, Spalding PB, et al. Natural resistance, iron and infection: a challenge for clinical medicine. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:251–8. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vallee BL, Rupley JA, Coombs TL, et al. The role of zinc in carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:64–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen M, Li E, Stanley SL., Jr Structural analysis of the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase activity of Entamoeba histolytica alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (EhADH2), a member of the ADHE enzyme family. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;137:201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Echave P, Tamarit J, Cabiscol E, et al. Novel antioxidant role of alcohol dehydrogenase E from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30193–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ulijasz AT, Andes DR, Glasner JD, et al. Regulation of iron transport in Streptococcus pneumoniae by RitR, an orphan response regulator. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:8123–36. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.8123-8136.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray MJ, Murray A, Murray CJ. The salutary effect of milk on amoebiasis and its reversal by iron. Br Med J. 1980;280:1351–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6228.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makkar RP, Sachdev GK, Malhotra V. Alcohol consumption, hepatic iron load and the risk of amoebic liver abscess: a case–control study. Intern Med. 2003;42:644–9. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.León-Sicairos N, Reyes-López M, Ordaz-Pichardo C, et al. Microbicidal action of lactoferrin and lactoferricin and their synergistic effect with metronidazole in Entamoeba histolytica. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:327–36. doi: 10.1139/o06-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latour NG, Reeves RE. An iron-requirement for growth of Entamoeba histolytica in culture, and the antiamebal activity of 7-iodo-8-hydroxy-quinoline-5-sulfonic acid. Exp Parasitol. 1965;17:203–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(65)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]