Abstract

Although tobacco use is reported by the majority of substance use disordered (SUD) youth, little work has examined tobacco focused interventions with this population. The present study is an initial investigation of the effect of a tobacco use intervention on adolescent SUD treatment outcomes. Participants were adolescents in SUD treatment taking part in a cigarette smoking intervention efficacy study, assessed at baseline and followed up at 3- and 6-months post-intervention. Analyses compared treatment and control groups on days using alcohol and drugs and proportion abstinent from substance use at follow up assessments. Adolescents in the treatment condition reported significantly fewer days of substance use and were somewhat more likely to be abstinent at 3-month follow up. These findings suggest that tobacco focused intervention may enhance SUD treatment outcome. The present study provides further evidence for the value of addressing tobacco use in the context of treatment for adolescent SUD’s.

Keywords: adolescent, substance abuse, smoking cessation, treatment outcome

Adolescent smoking remains a significant public health issue with 23% of high school seniors reporting smoking a cigarette in the past month and 14% smoking daily1. Smoking rates are substantially higher among adolescents with concurrent substance use disorders (SUD’s). Previous studies with youth receiving SUD treatment consistently find that almost all (over 80%) report current tobacco use, most are daily smokers2–5, and many become highly dependent, long-term tobacco users6–8.

Despite frequent cessation attempts, few adolescents stop smoking on their own9. Continued smoking is particularly likely among adolescents with substance abuse problems. For example, we have reported that 80% of those who smoked at the time of SUD treatment were still smoking four years later10. In a recent investigation we found that greater alcohol use over an 8-year period following treatment was associated with higher smoking rates11. However, even those with the best alcohol use outcomes had significantly elevated rates of smoking compared with the general population. Thus, adolescent smokers who receive treatment for SUD’s, but not their tobacco use, appear to be at heightened risk for smoking persistence.

Treating smoking during adolescence has the potential of preventing chronic tobacco use and the multitude of associated health risks. This concern is particularly acute for individuals with SUD’s given their heavy tobacco use. Tobacco-related health consequences may emerge relatively early as suggested by findings that respiratory problems were significantly more common among heavier smoking youth following SUD treatment3. Synergistic effects of tobacco and other substances of abuse indicate that concurrent heavy use leads to substantially increased health risks12, 13. The particular liability of individuals with SUD’s to these health consequences is highlighted by studies which have identified tobacco as a major contributor to mortality among adults treated for alcohol and other drug abuse14, 15.

Concern regarding the significant health consequences observed for smokers with concomitant SUD’s is reflected in a growing body of research on this topic. A recent meta-analysis of studies with adults in addictions treatment or recovery concluded that tobacco treatment interventions were effective in promoting short-term (post-treatment) but not long-term (≥ 6-months) smoking cessation16. Importantly, exposure to a tobacco cessation intervention while in SUD treatment was associated with an increased likelihood of long-term abstinence from drugs or alcohol. Thus, contrary to previous concerns17, smoking cessation interventions during addictions treatment appeared to enhance rather than compromise long-term outcome. This conclusion is bolstered by other studies with adults that have found quitting smoking is associated with greater rates of alcohol and drug abstinence 12-months following SUD treatment18, 19.

Possible mechanisms by which tobacco treatment interventions may support sobriety from alcohol and other drugs of abuse include reduced cue exposure, generalizability of relapse prevention techniques, increased sense of mastery, positive overall focus on health and change in lifestyle, or some other factor16. The priming theory represents one theoretical model that may account for the observed findings. This model, based on classical conditioning principles, suggests that following paired use, the use of one substance may act as a cue to prime the use of the second substance. Support for the priming theory comes from studies that have found a positive relationship between smoking and drinking. For instance, York and Hirsch20 found that alcoholics who smoke cigarettes have a higher quantity and frequency of alcohol intake relative to non-smoking alcoholics. Similarly, heavy drinking among smokers has been associated with increased quantity of cigarette use21 and an increased likelihood of remaining a smoker22. Thus, reduced smoking following a tobacco-focused intervention may limit exposure to substance use cues, thus leading to reduced substance involvement following treatment for alcohol and other drug use problems.

A growing literature demonstrates the value of smoking cessation intervention for adults with SUD’s. Despite evidence for negative health consequences and a clear need for treatment, few studies have evaluated smoking interventions with youth16. A recent meta-analysis identified 48 controlled investigations of adolescent tobacco treatment23. Of those referenced, only our recently published study24 examined tobacco cessation interventions in the context of adolescent substance abuse treatment. The trial compared a 6-session tobacco reduction and cessation intervention with a no-treatment control condition. Findings indicated significantly greater point prevalence abstinence at 3-months follow up among those in the treatment group compared to the waitlist control group. Thus, initial evidence supports the utility of addressing tobacco use at the time of adolescent SUD treatment.

The present investigation utilizes data from our recent clinical trial to examine the effect of the tobacco intervention on alcohol and drug use outcomes. We hypothesize that over a six month follow up period SUD youth assigned to the treatment condition would report significantly fewer days of alcohol and illicit drug use and significantly greater continuous abstinence from substance use than youth in the waitlist control condition. In addition, to assess the priming theory, we examined whether the effect of smoking treatment on substance use outcomes was mediated by changes in smoking behavior. Specifically, we hypothesized that reductions in rates of smoking would at least partially account for the relationship between receiving a smoking intervention and improved alcohol and other drug use outcomes. We believe the present investigation is the first to report on the effects of a tobacco use intervention on adolescent SUD treatment outcomes.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-four adolescent weekly cigarette smokers were recruited from four outpatient substance abuse treatment programs in Southern California. Excluded were adolescents with no resource person (i.e., parent or guardian) to corroborate tobacco, alcohol and other drug use status. The study was approved by the University of California, San Diego Institutional Review Board for conduct of research with human subjects. Consent was obtained from adolescent participants and a parent/legal guardian. Seventy-five percent of eligible youth consented to participate.

Design

The smoking intervention was delivered in group format and was integrated within the adolescent addiction treatment settings, such that all adolescents who smoked cigarettes were required to attend the smoking treatment when offered (participation in the outcome study was voluntary). The smoking intervention consisted of six weekly hour-long sessions intended to motivate and encourage changes in smoking behavior. A wait list control group formed the comparison condition. Participants were recruited into the outcome assessment study without knowing whether they would be assigned to the intervention or control condition. Eligible adolescents were provided with a brief description of the intervention and a detailed explanation of participation in the outcome assessment portion of the study. Upon completing each assessment, adolescents were reimbursed with gift certificates in the amounts of $25 for the baseline interview, $35 for 3-month and $45 for 6-month assessments. Participation in the intervention was offered to control subjects after completion of the 6-month follow up interview (these youth were informed regarding when and where the next available intervention group would take place). The intervention was offered to all eligible participants at a given site to prevent contamination, precluding random assignment of individuals. Rather, a sequential cohort design was employed whereby treatment condition was randomly assigned by site, with one assigned as a control and one active treatment for each cohort. In the subsequent cohort, after a minimum of 8-weeks following completion of an intervention group, conditions were reversed such that the previous control site received the intervention and vice versa. Groups of control and treatment participants were recruited simultaneously across sites, such that the assessment intervals were temporally matched for each. Follow up interviews were conducted 3- and 6-months after the final tobacco intervention group meeting. Further details on the intervention and treatment outcome study design have been published previously 24, 25.

Measures

Teen Smoking Questionnaire (TSQ)26

The TSQ incorporates items from various existing measures including age of tobacco use onset and past (lifetime) and recent (past 3-months) attempts at smoking cessation. Nicotine dependence was assessed using the modified Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ) criteria for adolescents (mFTQ)27, with a scoring range of 0 – 9. The mFTQ had poor internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .53) in the present sample. Similar levels of internal reliability have been reported for other versions of the FTQ28.

Time-Line Followback (TLFB)29

The TLFB gathered information on cigarette and alcohol use quantity and frequency and drug use frequency since the last assessment (prior 90 days at baseline). Good reliability and validity has been demonstrated for the TLFB for assessing adolescent cigarette use30 as well as alcohol and other drug use among adolescent substance abusers31.

Personal Involvement Screen (PIS)32

The PIS is a 29-item self-report scale of alcohol and drug use involvement. Items are scored on a 4-point scale (never, once or twice, sometimes, often) and summed to provide a single scale score, with higher scores reflecting greater substance use involvement. The measure has excellent psychometric properties and had a Cronbach’s alpha = .95 in the present sample.

Verification of self-reported substance use

Self-reported smoking abstinence was verified by saliva cotinine and alveolar carbon monoxide tests. None of the adolescent reports of smoking abstinence were discrepant with biochemical verification. Reports of smoking and substance use abstinence also were verified by corroborative reports from participating resource persons. All of the corroborative reports confirmed adolescent reports of abstinence from smoking or other substance use.

Analyses

Examination of distributional properties of smoking and substance use variables revealed that the sum of days using alcohol and other drugs was significantly skewed at each time point. A log base-10 transformation was applied which yielded a variable with acceptable distributional properties at all three time points (Skewness < 1.00). The effects of smoking cessation treatment on alcohol and other drug use was examined using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests and logistic regression analyses, controlling for the baseline value of the appropriate substance use outcome variable. Lastly, a mediation model was tested to examine associations between reductions in smoking and substance use outcomes.

Results

Sample descriptives

The sample (N=54) had a mean age of 16.1 years (range 13 – 18), was 22% female, and predominantly Caucasian (69%; 24% Hispanic). No baseline group differences were observed by treatment condition for age, gender, ethnicity, smoking history, nicotine dependence, past 30-day cigarette consumption, or substance use severity (all p > .30). However, at baseline, participants in the treatment condition were significantly more likely to report past 30-day substance use abstinence and fewer days using alcohol and drugs than control participants (p’s < .05). As such, analyses examining these outcomes included baseline values of the variables as covariates. Distribution of participants by treatment site differed significantly across treatment conditions, but was not significantly associated with 3- or 6-month substance use outcomes. Therefore, site was not considered as a covariate. Table 1 displays baseline cigarette and substance use variables by treatment condition.

Table 1.

Baseline cigarette and substance use variables by treatment condition.

| Treatment (N=27) | Control (N=27) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes per day: M(SD) | 7.85 (6.75) | 10.00 (5.88) |

| Smoking days past month: M(SD) | 24.81 (8.28) | 28.46 (2.78) |

| Nicotine dependence (mFTQ): M(SD) | 3.81 (1.64) | 3.68 (1.31) |

| Substance use days past month: M(SD) * | 11.27 (17.19) | 28.96 (33.09) |

| PIS score: M(SD) | 56.81 (20.37) | 55.30 (19.45) |

| Abstinent past 30 days (%) * | 63.0 | 21.4 |

Group comparison significant, p < .05

Attrition

Of the full sample, 39 (71%; 19 control, 20 intervention) completed 3-month and 37 (67%; 17 control, 20 intervention) completed 6-month follow-up interviews. Attrition analyses indicated no significant differences between missing and included subjects on demographic, smoking or substance use variables or by treatment condition. Additionally, subjects who were in a restrictive setting (e.g., residential treatment, jail) for over half of each follow up interval were excluded from analyses since their opportunities for smoking and substance use were constrained. At each follow up time point, three subjects were excluded for this reason, yielding 36 subjects (18 control, 18 intervention) available for analyses of 3-month outcomes and 34 (15 control, 19 intervention) for analyses of 6-month data.

Effects of smoking cessation treatment on alcohol and other drug use

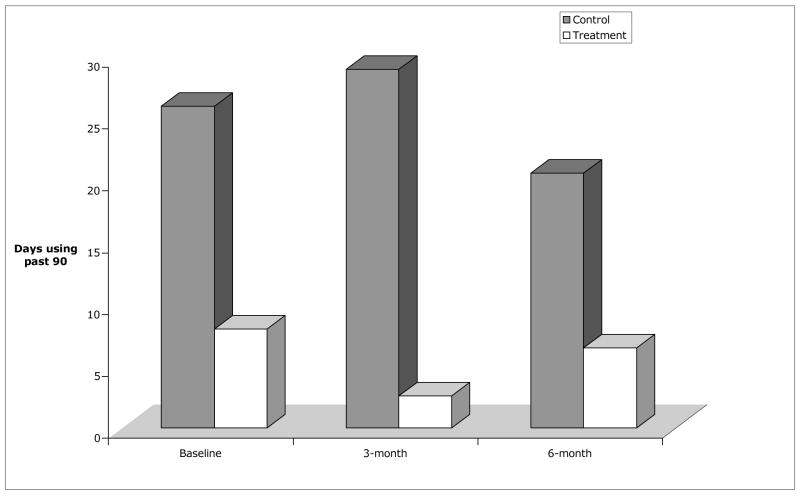

To examine the effect of smoking treatment on substance use outcomes, we compared treatment with control participants on past 30-day abstinence and total days of substance use at the 3- and 6-month follow up time points. [We were not able to consider PIS involvement scores as an outcome variable because of missing data on nine participants at the 3-month and six at the 6-month follow-up.] Participants in the treatment condition had significantly fewer days of substance use than controls at the 3-month follow up point after controlling for baseline days using (F (1,33) =6.56, p = .015). Similar results were obtained when analyzing the untransformed variable (F (1,33) =4.94, p = .033). An hierarchical logistic regression was used to examine the effect of experimental condition on 30-day abstinence at 3-months while controlling for baseline 30-day abstinence. The analysis resulted in a significant overall model (Χ2 (df=2) = 14.42, p = .002). The inremental effect of experimental condition did not reach statistical significance (Χ2 (df=1) = 2.51, p = .11), but was associated with an odds ratio of 3.6 (95% CI: 0.73 – 17.38, p = .12). This indicates that participants in the treatment condition were 3.6 times more likely than control participants to report 30-day abstinence at the 3-month follow up. However, at 6-months follow-up there was no significant effect of condition on days of use ((F (1,31) =1.08, p = .31) nor on 30-day abstinence (Χ2 (df=1) = .10, p = .75). Figure 1 shows average days of substance use across time points (untransformed for clarity of interpretation).

Figure 1.

Average number of days using alcohol and/or drugs in the 90 days at each assessment time point by treatment condition.

Treatment < Control at 3-months (p < .05) after controlling for baseline days using.

Next, we examined whether the effect of smoking treatment on 3-month SUD outcomes might be explained (i.e., mediated) by treatment-related reduction in smoking rate as assessed by number of cigarettes per smoking day. Mediation was tested following the procedures proposed by Baron and Kenny33. The first step involves demonstrating a significant relationship between the independent variable (treatment condition) and mediating variable (cigarettes per smoking day). This condition was met as smoking rate at 3-month follow-up differed significantly across treatment groups (treatment < control, p = .003). Next, the proposed mediator must be significantly associated with the dependent variable (days using). This condition was also met, as smoking rate was significantly associated with days of substance use (r=.41, p = .013). Finally, the relationship between the independent and dependent variables must no longer be significant after considering the influence of the mediating variable. A multiple regression analysis found that after considering the influence of smoking rate, treatment condition remained a significant predictor of 3-month substance use. Thus, mediation was not supported.

Discussion

The present study represents an initial effort to examine whether a tobacco focused intervention delivered at the time of adolescent SUD treatment has an effect on alcohol and drug use outcomes. Prior evaluation of the intervention indicated significant effects on tobacco abstinence at 3-months follow up24. Based on findings from the adult literature,16 we hypothesized that youth receiving intervention for their smoking also would evidence better substance use outcomes. Our predictions were partially supported in that, controlling for baseline levels of use, adolescents in the treatment condition reported less alcohol and other drug use at 3-months follow up compared to youth in the control condition. The differences, however, were not sustained at 6-months follow up. The findings support the importance of addressing tobacco use in the context of adolescent SUD treatment for short-term abstinence from both tobacco and other drugs of abuse.

A test of mediation to evaluate the priming theory indicated that the observed effect of smoking treatment on SUD outcomes at the 3-month assessment was not explained by the effect of treatment on smoking rate. Thus, the present results do not support a priming effect. The failure to find mediation may reflect that we examined smoking rate and substance use concurrently, whereas a true test would evaluate a mediator that temporally preceded the dependent variable. These findings suggest it is possible, at least in the short-term, that the tobacco focused intervention has a direct effect on alcohol and other drug use. Explanations for this effect may include increased exposure to relapse prevention strategies, heightened self-efficacy for behavior change, or increased motivation to address health behaviors. The lack of a significant relationship between treatment condition and substance use outcomes at the 6-month follow up may reflect a time-limited effect (as is commonly observed in addictive behavior treatment trials34), or may have resulted from the limited statistical power available with this small sample.

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting findings from the present study. Perhaps foremost, the small sample size provided limited statistical power to detect effects. Additionally, baseline differences on the substance use variables of interest required their inclusion as covariates, further reducing statistical power. It should be noted, however, that despite differences in substance use frequency across conditions, treatment and control groups had comparable levels of substance involvement severity as indicated by similar PIS scores at baseline. Nonetheless, it is possible that the observed differences in substance use outcomes were not entirely attributable to the smoking intervention. For example, baseline differences in substance use may have resulted from greater psychiatric comorbidity or longer substance abuse histories among control subjects, factors that may have influenced the observed differences in substance use outcomes. Finally, the small sample size and attrition at follow-up serves to limit generalizability of these findings and suggests caution in interpreting significant effects. More studies are needed to substantiate these findings.

To date, the issue of tobacco focused intervention in the context of adolescent SUD treatment has received limited research and clinical attention. One oft-noted barrier to addressing this issue is concern among SUD treatment participants and providers regarding the potential detrimental effects of smoking cessation efforts on abstinence from alcohol and other drugs17, 35. The present study questions the reality of these beliefs. Smoking intervention in the context of adolescent SUD treatment appeared to improve, rather than harm, alcohol and drug use outcomes.

The limitations of the present study caution against concluding that smoking treatment improves substance use outcomes. However, these results are consistent with previous studies indicating that smoking cessation is not detrimental to alcohol and other drug use outcomes.

Prior studies have demonstrated the successful integration of smoking focused interventions within adolescent SUD treatment programs2, 24, 26. In addition, there is mounting evidence for the efficacy of youth smoking cessation23, and the current findings provide added support for treatment of tobacco use within the realm of adolescent addiction treatment settings. Therefore, addressing tobacco use in the context of adolescent SUD treatment may yield multiple health benefits.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Research Project Grant 7RT-0142 from the California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program. Preparation of this article was supported in part by an Independent Investigator Award, DA017652, and a Career Development Award, DA018691, from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2005. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. (NIH PUblication No 06-5882) [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald CA, Roberts S, Descheemaeker N. Intentions to quit smoking in substance-abusing teens exposed to a tobacco program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000 Apr;18:291–308. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers MG, Brown SA. Smoking and health in substance abusing adolescents: A two year follow-up. Pediatrics. 1994;93:561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers MG, Macpherson L. Smoking Cessation Efforts Among Substance Abusing Adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arria AM, Dohey MA, Mezzich AC, Bukstein OG, Van Thiel DH. Self-reported health problems and physical symptomatology in adolescent alcohol abusers. J Adolesc Health. 1995 Mar;16:226–231. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00066-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Wagner EF. Cigarette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1602–1610. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay GB, Rainey J. Psychosocial and pharmacologic explanations of nicotine’s “gateway drug” function. J Sch Health. 1997;67:123–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood: demographic predictors of continuity and change. Health Psychol. 1996 Nov;15:478–484. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mermelstein R. Teen smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2003 Jun;12 (Suppl 1):i25–34. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_1.i25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers MG, Brown SA. Cigarette smoking four years following treatment for adolescent substance abuse. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 1997;7:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers MG, Doran NM, Brown SA. Is cigarette smoking related to alcohol use during the eight years following treatment for adolescent alcohol and other drug abuse? Alcohol Alcohol. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm025. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maier H, Dietz A, Gewelke U, Heller WD, Weidauer H. Tobacco and alcohol and the risk of head and neck cancer. Clin Investig. 1992;70:320. doi: 10.1007/BF00184668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bien TH, Burge R. Smoking and drinking: a review of the literature. Int J Addict. 1990;25:1429. doi: 10.3109/10826089009056229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. Role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA. 1996 April 10;275:1097–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hser YI, McCarthy WJ, Anglin MD. Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotics addicts. Prev Med. 1994;23:61–69. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prochaska JJ, Delucchi K, Hall SM. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions with individuals in substance abuse treatment or recovery. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 Dec;72:1144–1156. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bobo JK, Gilchrist LD, Schilling RF, Noach B, Schinke SP. Cigarette smoking cessation attempts by recovering alcoholics. Addict Behav. 1987;13:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klesges LM, Johnson KC, Somes G, Zbikowski S, Robinson L. Use of nicotine replacement therapy in adolescent smokers and nonsmokers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003 Jun;157:517–522. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.6.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemon SC, Friedmann PD, Stein MD. The impact of smoking cessation on drug abuse treatment outcome. Addict Behav. 2003 Sep;28:1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.York JL, Hirsch JA. Drinking patterns and health status in smoking and nonsmoking alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:666. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batel P, Pessine F, Maitre C, Peuff B. Relationship between alcohol and tobacco dependencies among alcoholics who smoke. Addiction. 1995;9:977. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90797711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray RP, Istvan JA, Voelker HT, Rigdon MA, Wallace MD. Level of involvement with alcohol and success at smoking cessation in the Lung Health Study. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:74. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sussman S, Sun P, Dent CW. A meta-analysis of teen cigarette smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2006 Sep;25:549–557. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers MG, Brown SA. A Controlled Study of a Cigarette Smoking Cessation Intervention for Adolescents in Substance Abuse Treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:230–233. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers MG, Brown SA, Kelly JF. A cigarette smoking intervention for substance abusing adolescents. Cog Behav Pract. 2000;7:64–82. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers MG, Brown SA, Kelly JF. A smoking intervention for substance abusing adolescents: Outcomes, predictors of cessation attempts, and post-treatment substance use. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2000;9:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prokhorov AV, Pallonen UE, Fava JL, Ding L. Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addict Behav. 1996;21:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991 Sep;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Time-line follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Totowa, NJ: Pergamon Press; 1992. pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis-Esquerre JM, Colby SM, Tevyaw TO, Eaton CA, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Validation of the timeline follow-back in the assessment of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005 Jul;79:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dennis ML, Funk R, Godley SH, Godley MD, Waldron H. Cross-validation of the alcohol and cannabis use measures in the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) and Timeline Followback (TLFB; Form 90) among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 2004;99:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henly GA, Winters KC. Personal Experience Inventory. Los Angeles CA: Western Psychological Services; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence: The COMBINE Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2006 May 3;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter KP, McCool RM, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia JS. Patients’ views on smoking cessation and tobacco harm reduction during drug treatment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4 (Suppl 2):S175–182. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000032735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]