Abstract

Calcium influx through plasma membrane store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) channels is triggered when the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ store is depleted — a homeostatic Ca2+ signalling mechanism that remained enigmatic for more than two decades. RNA-interference (RNAi) screening and molecular and cellular physiological analysis recently identified STIM1 as the mechanistic ‘missing link’ between the ER and the plasma membrane. STIM proteins sense the depletion of Ca2+ from the ER, oligomerize, translocate to junctions adjacent to the plasma membrane, organize Orai or TRPC (transient receptor potential cation) channels into clusters and open these channels to bring about SOC entry.

Cells are preoccupied by the control of cytosolic calcium concentration, and with good reason. Calcium ions shuttle into and out of the cytosol — transported across membranes by channels, exchangers and pumps that regulate flux across the ER, mitochondrial and plasma membranes. Calcium regulates both rapid events such as cytoskeleton remodelling or release of vesicle contents, and slower ones such as transcriptional changes. Moreover, sustained cytosolic calcium elevations can lead to unwanted cellular activation or apoptosis.

Among the long-standing mysteries in the Ca2+ signalling field is the nature of feedback mechanisms between the ER and the plasma membrane. Studies in the late 1980s and 1990s established that the depletion per se of ER Ca2+, but not the resulting rise of cytosolic Ca2+, is the initiating signal that, following InsP3-induced release of ER Ca2+, triggers SOC entry (SOCE) through Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane1. The best-characterized SOC current was, and still is, the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) current in lymphocytes and mast cells2–4. However, the molecular mechanism remained undefined until recently. The key breakthroughs came from RNAi screening, which first identified STIM proteins as the molecular link from ER Ca2+ store depletion to SOCE and CRAC channel activation in the plasma membrane, and then identified Orai (CRACM) proteins that comprise the CRAC channel pore-forming subunit. STIM proteins will be referred to generically as STIM, the Drosophila melanogaster protein as Stim and the two mammalian homologues as STIM1 and STIM2.

Origins of STIM

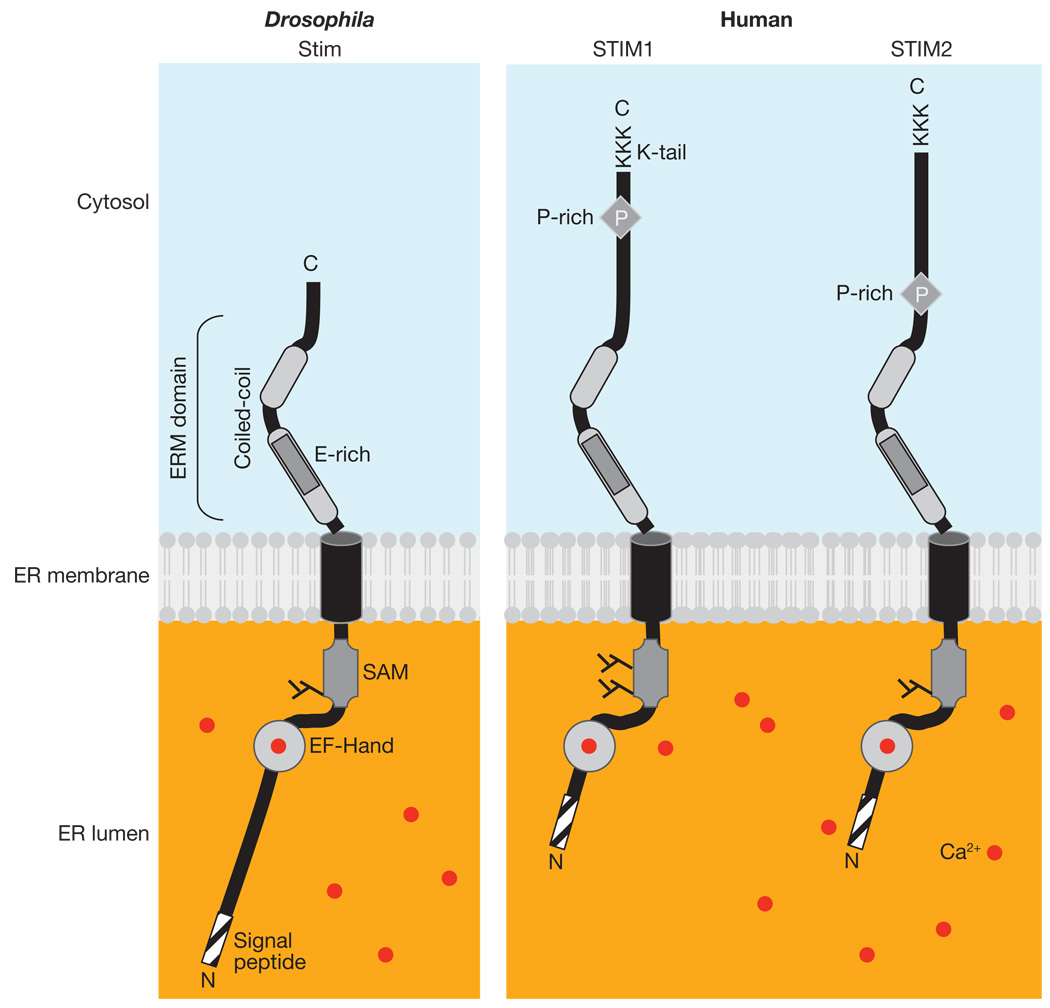

STIM proteins first came to light outside the Ca2+ signalling field. STIM1 was originally identified in a library screen by its ability to confer binding of pre-B lymphocytes to stromal cells. Originally named SIM (stromal interacting molecule)5, the name later morphed into STIM — fortuitously suggestive of its function in stimulating calcium influx across the plasma membrane. Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans have one STIM protein, but representative amphibians, birds and mammals have two STIM homologues (and teleost fish have four)6,7, suggesting gene duplication at the invertebrate-vertebrate transition. In addition, STIM1 (formerly known as GOK)8 was implicated in cell transformation and growth by its chromosomal localization (human 11p15.5) to a region associated with paediatric malignancies, and by its ability to induce cell death when transfected into rhabdomyosarcoma and rhabdoid tumour cells9. It was originally characterized biochemically as a glycosylated phosphoprotein with ~25% expression in the plasma membrane by surface biotinylation6,10,11. The human STIM2 gene, sharing 61% sequence identity with STIM1, localizes in a region (4p15.1) implicated in squamous carcinoma and breast tumours6. The sole Drosophila homologue, Stim, has 31% identity and 60% sequence similarity to STIM1. STIM proteins from Drosophila and mammals are shown diagrammatically in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Domains of STIM proteins. Drosophila and human STIM proteins are situated in the ER membrane. Modules of STIM1, STIM2 and Stim include: the signal peptide, the predicted EF-hand and SAM domains, the transmembrane region and two regions predicted to form coiled-coil structures comprising the ERM domain. Proline-rich domains (P) and the lysine-rich C-terminal regions are unique to the mammalian STIM family members. Drosophila Stim contains an N-terminal sequence in the ER that is not present in either STIM1 or STIM2. The N-linked glycosylation sites at the SAM domain, experimentally verified for STIM1 (refs 11, 85), are also indicated. Background colours represent basal Ca2+ concentrations of ~50 nM in the cytosol and > 400 µM in the ER lumen. Ca2+ ions are shown as red dots, including Ca2+ bound to the EF-hand domain.

Inspection of the primary polypeptide sequence of STIM proteins reveals a modular construction. Two protein–protein interaction domains are separated by a single membrane-spanning segment and, as a type I membrane protein, the amino terminus is predicted to reside either within the ER lumen or facing the extracellular space. Between the N-terminal signal peptide sequence and the sterile alpha motif (SAM) protein interaction domain, two adjacent regions containing negative charges, one typical of an EF-hand Ca2+-binding domain, are found. At the other end, in the cytoplasm, a lengthy bipartite coiled-coil is predicted within a region containing an ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) domain leading to the C terminus. This end of the molecule diverges substantially, the Drosophila (and C. elegans) protein notably lacking a proline-rich region and a lysine-rich tail.

RNAi screens identify STIM and Orai

The key breakthroughs in identifying the molecular constituents of SOC signalling arose from RNAi screening. A critical role of STIM in SOCE was first revealed by two concurrent and independent candidate RNAi screens12,13, using thapsigargin to deplete the ER Ca2+ store. Thapsigargin blocks the ER-resident SERCA (sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium) pump, causing a decline in luminal Ca2+ store content as Ca2+ leaks out of the ER passively, unopposed by active re-uptake through the pump. Drosophila S2 cells used in one screen13 have functional CRAC currents closely similar in activation requirements and biophysical characteristics to those in human T lymphocytes14. Hits were defined by decreased SOCE and confirmed in single cells by Ca2+ imaging and whole-cell recording. The S2 cell screen yielded one hit (Stim)13, and the human HeLa cell screen identified both mammalian homologues, STIM1 and STIM2 (ref. 12). It soon became clear that several mammalian cell types rely primarily on STIM1 for SOCE and CRAC channel activation12,13,15; an additional screen showed that STIM2 functions in regulating basal Ca2+ levels16.

STIM triggers SOCE but does not form the CRAC channel itself. Following the success of the candidate screening approach, the search for the CRAC channel continued as genome-wide RNAi screening in S2 cells was performed independently by three research groups17–19. This led to the identification of several additional genes required for Ca2+ signalling, including the previously unheralded Orai (also known as CRACM, formerly known as olf186-F ), a Drosophila gene with three mammalian homologues. A parallel genetic screen by one of the three groups led to the remarkable discovery that a point mutation (corresponding to R91W) in human Orai1 on chromosome 12 causes a rare but lethal disorder SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency disorder) — the first identified channelopathy of the immune system17. Orai proteins have four predicted transmembrane segments, but apart from being a multi-span transmembrane protein Orai has no other similarity to known ion channels. Evidence that Orai forms the CRAC channel itself came from two further discoveries. First, the unique biophysical fingerprint of the CRAC channel in patch clamp studies is duplicated, but with currents that are amplified 10 to 100-fold, when STIM and Orai are overexpressed together in heterologous cells19–22. Second, Orai and Orai1 were confirmed as CRAC channel pore-forming subunits by the marked alteration of ion selectivity that results from point mutation of a key glutamate residue in the loop between transmembrane segments 1 and 2 (refs 23–25).

Sensing luminal ER Ca2+

The essential function of STIM as a non-channel intermediary of SOCE and CRAC channel activation has been explored by mutagenesis and subcellular localization. The presence of an EF-hand motif near the N terminus, localized in the ER lumen, suggested a role in sensing ER Ca2+. It was soon discovered that expression of EF-hand mutants engineered to prevent Ca2+ binding resulted in constitutive Ca2+ influx and CRAC channel activation, but without depletion of the ER Ca2+ store12,26. This ability of the EF-hand mutants to bypass the requirement for Ca2+ store depletion convincingly demonstrated that the Ca2+-unbound state of STIM leads to CRAC channel activation. The resting concentration of Ca2+ within the ER lumen is hundreds of micromolar — much higher than in the cytoplasm — and is maintained by ongoing activity of the SERCA pump. Ca2+ binding to the isolated EF-SAM portion of STIM1 was shown to have a dissociation constant in the range of hundreds of micromolar and a 1:1 binding stoichiometry27. Low-affinity binding of Ca2+ to the EF-hand domain is compatible with the proposal that Ca2+ is bound when the ER store is full and STIM releases Ca2+ when the ER is depleted, thus initiating a process that leads to CRAC channel activation.

Signal initiation by oligomerization

In the basal state when ER Ca2+ stores are filled, STIM is a dimer stabilized by C-terminal coiled-coil interactions, as shown by several lines of evidence. Intact STIM proteins heteromultimerize under basal conditions6,28,29, and Stim forms dimers30. Moreover, the isolated C-terminal portion of STIM1 forms dimers31, whereas the isolated N-terminal ER-SAM domain is monomeric at basal ER Ca2+ concentration. When the ER Ca2+ store is depleted, further STIM1 oligomerization occurs within seconds in intact cells32,33, and this is mediated by the SAM domain adjacent to the EF-hand domain, as shown by the formation of multimers at reduced Ca2+ levels in biochemical and nuclear magnetic resonance structural studies of the isolated N-terminal portion of STIM1 (refs 34, 35). In intact cells, oligomerization precedes and triggers translocation of STIM to the plasma membrane and activation of CRAC channel activity32,33,36.

Conveying the message to the plasma membrane

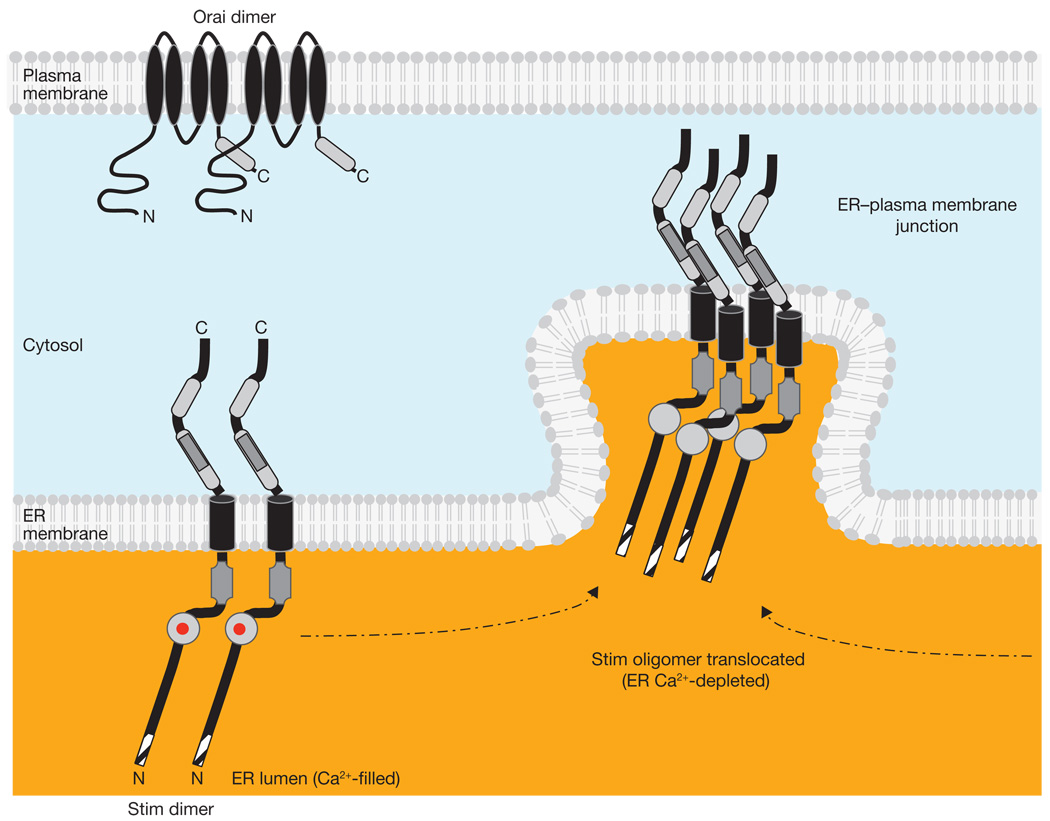

After Ca2+ store depletion, the EF-hand domain releases bound Ca2+ and oligomers of STIM physically translocate ‘empty-handed’, thereby conveying the message to the plasma membrane that the ER store has been depleted (Fig. 2). Native STIM1 and tagged constructs were first shown by light microscopy, and then by electron microscopy, to form clusters (also termed ‘puncta’ or ‘hotspots’, with surface areas in the order of 1–10 µm2) immediately adjacent to the plasma membrane, following Ca2+ store depletion12,20,26,28,37. Whereas native untagged STIM1 colocalized with ER-resident proteins in the resting state when the Ca2+ store was filled, it was shown to translocate to the plasma membrane following store depletion26. Moreover, activating EF-hand mutant STIM1 proteins were localized predominantly at the plasma membrane even when the Ca2+ store remained full12,26. The marked redistribution of STIM1 after Ca2+ store depletion was not accompanied by any obvious changes in the bulk ER structure12,26,37. Instead, as seen from Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements, ER STIM1 oligomerizes and subsequently accumulates at specific predetermined foci in the peripheral ER32,33,38,39, representing points of close ER–plasma membrane apposition37. Total internal reflectance fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy placed yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged STIM1 clusters to within 100–200 nm of the cell surface12,28,32,37 (Supplementary Information, Movie 1), and electron microscopy visualization of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-tagged STIM1 demonstrated that it migrates to within 10–25 nm of the plasma membrane37. Tagging may prevent surface expression of STIM1 (Box 1), but tagged proteins are effective in evoking SOCE and CRAC currents indicating that acute insertion of STIM1 into the plasma membrane is not a required step. Clustering of STIM1 adjacent to the plasma membrane is rapid (occurring before CRAC channels open), spatially reproducible and rapidly reversible on signal termination and refilling of the ER Ca2+ store32,38–40. In addition to the refilling of the ER Ca2+ store, the disassembly of STIM1 clusters may also result from Ca2+ influx and the resulting rise in cytosolic Ca2+, implying a local negative feedback mechanism that may contribute to CRAC channel inactivation 41.

Figure 2.

STIM Ca2+ sensor, signal initiation and messenger functions. STIM molecules are shown in the basal state as dimers (left); the Ca2+ sensor EF-hand domain has bound Ca2+ (red dots) when the ER Ca2+ store is filled. Background colours represent basal Ca2+ concentrations of ~50 nM in the cytosol and > 400 µM in the ER lumen. ER Ca2+ store depletion causes Ca2+ to unbind from the low affinity EF-hand of STIM; this is the molecular switch that leads to STIM oligomerization and translocation (dashed arrows) to ER–plasma membrane junctions. Non-conducting Orai channel subunits are shown as dimers.

Box 1 Surface expression, plasma membrane insertion and tags

Native STIM1 is localized primarily in the ER but is also detected by surface biotinylation, indicative of plasma membrane expression of a sizeable fraction (20–30%) of the total pool 10,26,82,83. Moreover, it was reported to insert into the plasma membrane following store depletion by thapsigargin treatment26,83. Neither STIM2 nor EF-hand mutant STIM1 was detected under conditions that revealed plasma membrane expression through surface accessible biotinylated STIM115,82. However, surface expression experiments using anti-tag antibodies, electron microscopy and the failure to observe acute quenching of pH-sensitive forms of GFP by acidic pH did not show covalently tagged STIM1 in the plasma membrane (when tagged with GFP, YFP, HRP or HA— haemagglutinin — at the N-terminus12,20,32,37,50,84 or CFP — cyan fluorescent protein — at the C-terminus84). Thus, it appears that trafficking of STIM1 to the plasma membrane may be perturbed by protein tags. Consistently, a very small tag (hexahistidine) at the N terminus of STIM1 was shown to externalize following thapsigargin treatment, whereas co-expressed C-terminal CFP-tagged STIM1 remained within the ER84. Direct fusion events of STIM1- containing ER tubules to lipid raft domains of the plasma membrane have been reported using C-terminal-tagged YFP imaged by TIRF microscopy45. Membrane insertion will clearly need to be evaluated using other methods. Collectively, these results imply that STIM1 is in the plasma membrane and the ER, that tags (N-terminal YFP, GFP, HRP, HA and C-terminal CFP) can prevent surface localization and that the native protein may insert acutely following store depletion. It now seems clear that regardless of whether STIM1 is present in the plasma membrane or inserts acutely into it following store depletion, translocation to the plasma membrane without STIM1 insertion is sufficient to activate the CRAC channel, as STIM1 or Stim tagged with YFP or with other fluorescent proteins functions perfectly well in activating robust SOC influx and CRAC current12,20,30,32,37,50. Moreover, the presence of plasma membrane STIM1 is not required for ER-resident-tagged STIM1 to function in triggering SOCE28. Plasma membrane STIM1 may be involved with other functions such as cell adhesion, as originally suggested in the first report on ‘SIM’, where it was defined as a protein required for adhesion to stroma5, and as suggested in very recent evidence favouring a role of plasma membrane STIM1 in SOC channel activation82. In addition, STIM1 in the plasma membrane may be essential for activation of arachidonate-regulated Ca2+ (ARC) channels85 that include ORAI1 and ORAI3 as essential components86.

Oligomerization of STIM is necessary and sufficient for its translocation to ER–plasma membrane junctions36. STIM1 clustering and translocation begins when ER luminal Ca2+ concentration falls below ~300 µM16,36, consistent with low-affinity binding of Ca2+ to the EF-hand–SAM region of STIM1 (ref. 27). STIM1 clustering at the plasma membrane was found to be heavily dependent on ER Ca2+ concentration (a Hill coefficient of ~4, far steeper than the Ca2+ concentration dependence of binding to the EF-hand domain of STIM1), suggesting that STIM1 oligomers, but not monomers or dimers, accumulate near the plasma membrane. Moreover, CRAC channel activation closely matched the steep Ca2+ dependence of STIM1 aggregation and translocation to the peripheral ER, suggesting sequential processes triggered by aggregation36. Importantly, chemically induced oligomerization of STIM1 also resulted in translocation and activation of CRAC channels without ER Ca2+ store depletion36. These key experiments confirm that STIM oligomerization is sufficient to induce translocation to the plasma membrane and CRAC channel activation.

During even modest depletion of the ER Ca2+ store, STIM2 formed clusters at the plasma membrane, even as STIM1 remained localized in the bulk ER16. A distinct function of STIM2 in basal Ca2+ regulation, STIM2 having a lower ‘effective affinity’ for luminal ER Ca2+ than STIM1 (400 and 200 µM, respectively), is probably linked to differences in coupling between the EF-hand domain and the adjacent SAM domain34.

So how does STIM migrate within the ER under basal conditions and then accumulate at the plasma membrane following store depletion? When the ER Ca2+ store is filled, STIM1 colocalizes with microtubules and appears to have a role in organizing and remodelling the ER, as the tubulovesicular distribution of STIM1 and the ER itself are disrupted when microtubules are depolymerized28,42,43 and ER extension is stimulated by STIM1 overexpression43. STIM1 binds to the microtubule plus-end tracking protein EB1 (end binding protein 1) and associates with tubulin at the growing plus-end of microtubules43. TIRF microscopy imaging revealed rapid comet-like movement of ER STIM1 along fibrillar microtubule tracks near the cell surface28,43–45 (Supplementary Information, Movie 1). As a plus-end microtubule-tracking protein, STIM1 can cover long distances within the cell. STIM1 proteins in tubular ER structures have been reported to associate with lipid raft regions of the plasma membrane, colocalizing with the ganglioside GM1 and caveolin45,46. A role for microtubules in SOCE and CRAC channel function remains controversial, some studies showing partial inhibition upon microtubule depolymerization44,47 and others reporting no effect28,48. Microtubules interact with, and appear to guide, the intracellular trafficking of STIM1 as it migrates within the ER under basal conditions, but are neither required for cluster formation nor for functional activation of SOCE or CRAC channels when STIM1 is overexpressed28,44.

Organizing the elementary unit of Ca2+ signalling

After ER Ca2+ store depletion, STIM clusters are found in the ER, close enough to the cell surface to allow for direct interaction with plasma membrane proteins. There are important precedents for ER–plasma membrane protein–protein signalling interactions, including excitation-contraction coupling in muscle. However, unlike STIM-mediated Ca2+ signalling, the primary signal in excitation-contraction coupling is from the plasma membrane to the sarcoplasmic reticulum, through a molecular coupling between plasmalemmal voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. In contrast, CRAC channel activation involves physical migration of ER-resident STIM to ER–plasma membrane junctions and subsequent aggregation of the Ca2+ influx channel. Not only does STIM serve as both Ca2+ sensor and messenger, it also organizes Orai subunits into adjacent plasma membrane clusters30,49,50. The clusters of messenger STIM and corresponding Orai channel proteins have been termed the ‘elementary unit’ of SOCE and CRAC channel activation, as Ca2+ influx through CRAC channels occurs precisely at STIM–Orai clusters49. Induced aggregation of Orai channels serves to concentrate local Ca2+ signalling at the particular regions of the cell where STIM and Orai cluster. Based on cluster size and number, estimates of the single-channel CRAC conductance, total number of channels per cell19 and on direct fluorescence measurements31, STIM and Orai clusters contain hundreds to thousands of molecules packed into a few square micrometres in the overexpression systems.

A particularly notable example of altered subcellular localization of STIM and Orai occurs at the region of contact — the ‘immunological synapse’ — between lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells. When a T lymphocyte contacts an antigen-presenting cell, local signalling events lead rapidly to a cascade of tyrosine phosphorylation, InsP3 generation and release of Ca2+ from the ER store. STIM1 and Orai1 colocalize to the immunological synapse, resulting in localized Ca2+ entry into the T cell region immediately next to the synapse51. STIM1–Orai1 clustering at the synapse was confirmed and also detected at the distal pole of the T cell in cap-like membrane aggregates52. Interestingly, following the initial phase of T cell activation, all three Orai isoforms and STIM1 are upregulated and Ca2+ signalling is enhanced, implying a positive feedback mechanism that sensitizes T cells to antigen during the first day of an immune response51.

Orai channel activation by STIM

Stim activates Orai19, and STIM1 couples functionally to all three Orai homologues in expression systems20,53,54, forming very large CRAC-like currents with subtle differences in biophysical properties after store depletion. Evidence for a physical interaction between Stim and Orai was first obtained by co-immunoprecipitation studies demonstrating an increased interaction strength after Ca2+ store depletion25. A direct nanoscale molecular interaction was suggested by FRET measurements between donor and acceptor fluorescent protein tags at the C termini of STIM1 and Orai1 (refs 33, 42, 52, 55). Abundant evidence indicates that the cytosolic C terminus of STIM functions as the effector domain to open Orai and TRPC channels. Most importantly, the truncated C-terminal portion of either Stim or STIM1 (‘C-STIM’) is sufficient, when expressed as a cytosolic protein, to constitutively activate native CRAC current, as well as expressed Orai, Orai1 and TRPC1 channels30,31,33,56–58, bypassing the requirement for Ca2+ store depletion. Cytosolic C-STIM was found by colocalization, co-immunoprecipitation and FRET analysis to interact with Orai independent of ER Ca2+ store depletion, but without forming clusters typical of full-length STIM after store depletion30,31,33. Together, these studies identify the C terminus as the effector of STIM and show that CRAC channel activation does not necessarily require cluster formation. Further deletion analysis and fragment-expression experiments have recently defined even smaller portions of STIM1 as the effector59–61. A minimal activating sequence of approximately 100 amino acids spanning the distal coiled-coil of STIM1 was shown to activate the Orai1 current60,61 and to bind directly to purified Orai1 protein60. Interestingly, the Orai1 current induced by the minimal fragment of STIM1 reportedly lacks the normal CRAC channel property of rapid Ca2+-dependent inactivation60,62.

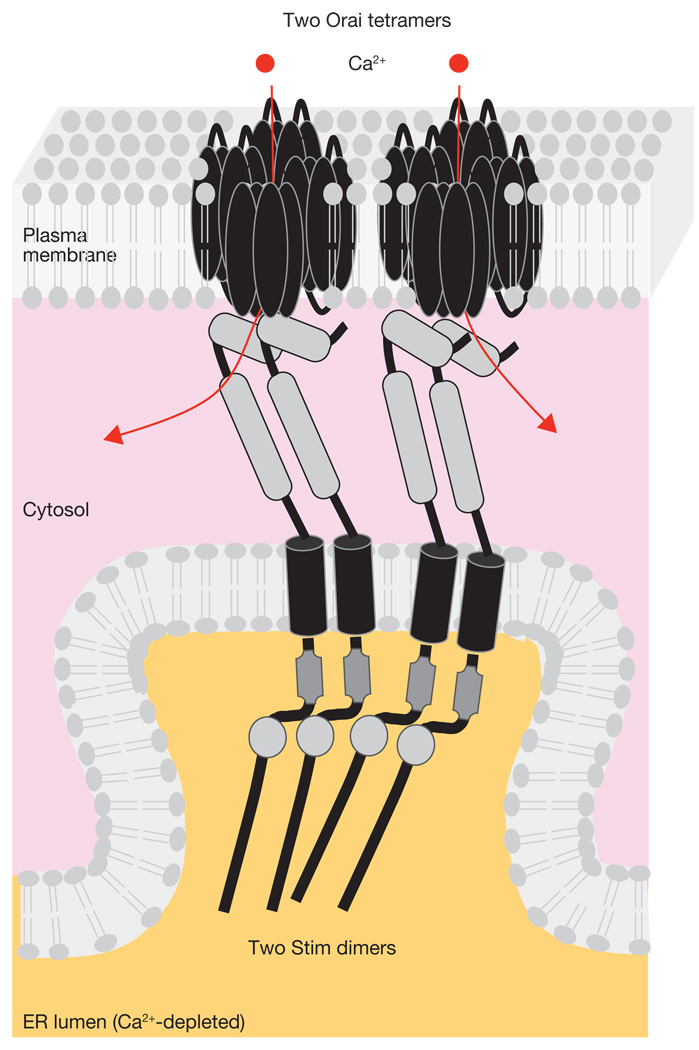

Stoichiometry: STIM in Orai channel subunit assembly

Many ion channels are stable tetramers that surround a conducting pore, but examples of trimers, pentamers and hexamers are also well known. STIM1 oligomerization is sufficient to cause its translocation adjacent to the plasma membrane where activation of Orai1 channels occurs36 (Fig. 3). How many STIM and Orai molecules are required to activate the channel? To date, four studies have investigated the oligomerization status of Orai. In biochemical experiments (glycerol gradient centrifugation, native gel systems and cross-linking)30,63, Orai appears predominantly as a stable dimer. Yet strong functional evidence favouring a tetramer also exists; tandem tetramers of Orai1 were resistant to dominant-negative suppression by a non-conducting Orai1 monomer64. Two recent studies took the different, single-molecule approach of counting the number of photobleaching steps to determine the number of GFP (green fluorescent protein)-tagged Orai subunits per channel30,31. Both studies showed that a tetramer predominates when the channel is activated. However, using biochemical analysis and single-molecule photobleaching, we found that when Orai was expressed alone (without Stim or activating C-Stim) it appeared as a stable dimer and no change in oligomerization status was seen in resting cells expressing Stim and Orai30. In contrast, another study found that STIM1 and Orai1 co-expression always resulted in tetrameric Orai1 in both closed and open states31. Further studies are needed to determine the kinetics and reversibility of the dimer-to-tetramer transition. A similar photobleaching approach applied to C-STIM1 suggests that two STIM1 molecules are required to activate the tetrameric Orai channel31.

Figure 3.

STIM-mediated organization of the elementary unit and activation of Orai channels. STIM accumulation induces Orai channels to cluster in the adjacent plasma membrane. The C-terminal effector domain of STIM induces Orai channels to open by direct binding of the distal coiled-coil domain, and Ca2+ enters the cell (red arrows). Two STIMs can activate a single CRAC channel consisting of an Orai tetramer; channel activation of Orai may involve a preliminary step of assembling Orai dimers into a functional tetramer. Background colours represent changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (from that in the basal state as represented in Fig 2 and Fig 3) to > 1 µM due to Ca2+ entry, and ER luminal Ca2+ to < 300 µM.

TRPC channel activation by STIM1

Are all SOC channels actually STIM-Operated Ca2+ channels with a variety of different pore-forming subunits? The coupling between STIM1 and Ca2+-permeable channels appears to be promiscuous, a property that may potentially help to resolve an often tendentious discussion of what is, and what is not, a SOC channel. From a biophysical perspective, it has been puzzling to note the very different properties of ion selectivity and rectification of SOC channels in various cell types. CRAC channels in the immune system are very selective for Ca2+, have an inwardly rectifying current-voltage relationship and an unusually low single-channel conductance in the femtosiemens range; in contrast,TRPC channels are less Ca2+-selective and have more linear current-voltage relationships and higher single channel conductances in the picosiemens range. The promiscuity of STIM1 coupling potentially resolves this conundrum. ‘Classic’ CRAC current is identified as originating from Orai channels, whereas the less selective SOC influx may be due to TRPC family members. So far, STIM1 has been implicated in activating Ca2+-permeable TRPC1, C2, C3, C4, C5 and C6 (but not TRPC7) channels45,46,56,61,65–70. As shown previously for native CRAC channels, the C terminus of STIM1 activates TRPC1 and TRPC3 channels and interacts with TRPC1, C2, C4 and C5 (as shown by co-immunoprecipitation)56,57, leading to the conclusion that STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels and confers function as SOC channels57. For TRPC1, channel activation is mediated through a charge–charge interaction that requires the C-terminal lysine-rich domain of STIM1 (ref. 71). TRPC1 is reportedly recruited by STIM1 to lipid raft domains in the surface membrane, resulting in a store-dependent mode of TRPC1 channel activation45,46. A further level of complexity was suggested on the basis of RNAi suppression, dominant-negative suppression and biochemical pulldown experiments that point to interactions between TRPC and Orai channels68,70,72,73. However, the functional relationship between STIM, TRPC and Orai proteins will need further investigation to confirm the extent of inter-family heteromultimerization and to ensure that TRPC channels are activated directly by STIM1 following store depletion and not through an indirect route.

Conclusion and remaining questions

In this review, the modular organization and five distinct functions of STIM that link ER Ca2+ store depletion to the activation of SOC channels in the plasma membrane are highlighted: Ca2+ sensing, signal initiation by oligomerization, translocation to ER–plasma membrane junctions, inducing Orai subunits to cluster and activating Ca2+ influx. This entire intracellular spatiotemporal signalling sequence can occur within a minute in small cells. Molecular feedback mediated by STIM1 shuttling between the ER and the plasma membrane ensures that Ca2+ influx occurs locally across the plasma membrane, refilling the ER Ca2+ store near the site of signal initiation in large cells and producing sustained and global Ca2+ signalling in small cells. Local Ca2+ signalling is likely to have important consequences for amplifying the Ca2+ signal near lipid raft domains as, for example, in the region of the immunological synapse. Knockout and RNAi knockdown experiments suggest important functions and potential therapeutic targets that involve Ca2+ signalling and homeostasis during development and in several different organ systems and cell types (Box 2).

Box 2 Knockouts, STIMopathies and knockdown

Corresponding to its widespread expression pattern and documented role in Ca2+ signalling, Stim1 knockout has devastating effects in vivo. Stim1−/− mice generated in various ways perished in utero or soon after birth of respiratory failure, although early embryos appeared to develop normally80,87–89. STIM2-deficient animals were born, but died at 4–5 weeks88. A difference in STIM1 and STIM2 function has been confirmed in vivo in T cells from single- and double-knockout mice88. Consistent with RNAi studies on cells in culture12,13, deletion of Stim1 resulted in a more profound reduction of SOCE in primary T cells and embryonic fibroblasts than deletion of Stim2 (ref. 88). CRAC currents were nearly abolished in T cells when Stim1 was deleted but were scarcely reduced by Stim2 knockout. Yet effects on cytokine production were profound in both Stim1- and Stim2-knockout T cells. One possible explanation is that STIM2 continues to provide sufficient Ca2+ influx to promote gene expression responses at late times when STIM1 has redistributed back to the bulk ER. CD4-CRE mice doubly deficient in both STIM1 and STIM2 developed a lymphoproliferative disorder due to impaired function of regulatory T cells88. Stim1 knockout also profoundly reduced SOCE in fetal liver-derived mast cells and acute degranulation was nearly abolished87. Secretion of cytokines was strongly reduced, and in heterozygous Stim1+/− mice anaphylactic responses were mildly reduced. A gene-trap knockout to generate Stim1−/− mice resulted in neonatal lethality with growth retardation and a severe skeletal myopathy89. Functional analysis of myotubes from gene-trap-knockout Stim1gt/gt mice indicated reduced SOCE, attenuated CRAC-like current and increased fatiguability during repetitive action potentials. A role of STIM1 in platelets relating to cerebrovascular function was also inferred80. SOCE, agonist-dependent Ca2+ influx and platelet aggregation was reduced in platelets from STIM1-deficient mice, also generated by insertion of an intronic gene-trap cassette. Of potential clinical significance, bone-marrow chimaeric mice with STIM1 deficiency in haematopoietic cells, including platelets, had improved outcomes in a brain infarction model of stroke using transient occlusion of a cerebral artery to induce neuronal damage80. STIM1 also has a vital role in FCγ receptor-mediated functions in macrophages, including the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and phagocytosis90. In the same study, mice lacking STIM1 in haematopoietic cells were shown to be resistant in experimental models of thrombocytopenia and autoimmune hemolytic anaemia. Furthermore, transgenic mice expressing an EF-hand mutant STIM1 exhibited a bleeding disorder associated with elevated Ca2+ and reduced survival of platelets that led to reduced clotting in this induced ‘STIMopathy’ (ref. 91). Collectively, these studies show that Ca2+ signalling was dramatically reduced in T lymphocytes, fibroblasts, mast cells, skeletal muscle, platelets and macrophages from Stim1 knockouts.

Recently, an immune deficiency syndrome due to mutation of STIM1 was identified in a human family92. This first human STIMopathy arises from a truncation mutation in the SAM domain that introduces a premature STOP codon and results in undetectable levels of Stim1 mRNA and protein expression. SOCE was absent in patient fibroblasts, and the patients exhibited a complex syndrome of combined immunodeficiency with infections and autoimmunity associated with hepatosplenomegaly, hemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and reduced numbers of regulatory T cells. In addition, patients exhibited muscular hypotonia and an enamel dentition defect, similarly to patients with immunodeficiency due to mutations in Orai1.

STIM1 has also been implicated by RNAi knockdown of SOCE or CRAC channel function in a variety of primary cells and cell lines, including: Jurkat T13, HEK293 (refs 13, 93), HeLa12,94, PC12 (ref. 95), neuroblastoma/glioma75 and breast cancer96 cell lines; airway and vascular smooth muscle75,97–101; hepatocytes102 and liver cell lines103–105; and salivary and mandibular gland cells70. In addition, parallels in STIM1 expression and SOCE function are reported in primary megakaryocytes and platelets106, resting and activated human T cells51 and vascular smooth muscle107,108; STIM1 translocation has been studied in a pancreatic cell line40.

Despite rapid progress since the initial discovery of STIM’s role in SOCE, we still do not understand several aspects of how STIM functions. We are uncertain how ER-resident STIM migrates rapidly along microtubules, how it accumulates at the plasma membrane following store depletion and how it is retrieved when the Ca2+ store is refilled. Many questions are posed. Are there additional scaffolding functions of STIM to anchor microtubules or to keep the ER intact? Is STIM translocation active or passive? What defines ER–plasma membrane junctions and how stable is the organization? When STIM arrives at the plasma membrane, does it induce Orai to accumulate using a diffusion trap? Or something else? Is the assembly of Orai dimers into a tetramer a dynamic and rapidly reversible process during channel gating? Finally, how exactly does STIM open the Ca2+ channel formed by Orai?

Other than STIM and Orai, there may be additional molecular components to the mechanism. After all, there were dozens of hits in genome-wide screens for SOCE function; to date, however, attention has been focused on STIM and Orai. Is there a ‘CRAC-osome’, and if so what is it? Suggestions that there are other components include size constraints involved in migration of Orai1 into clusters39, evidence old and recent that a Ca2+ influx factor might be involved74–76 and evidence that several proteins can be recruited to clusters77. On the other hand, overexpression of STIM and Orai alone, without a third protein, amplifies the number of functional CRAC channels to a remarkably high expression level (> 105 per cell) in many cell types, indicating that expression levels of other proteins are not limiting, at least up to very high channel densities. Furthermore, EF-hand mutant STIM1 and C-STIM N-terminal fragments bypass ER Ca2+ store depletion in activating robust CRAC current, arguing strongly against the hypothesis that a Ca2+ influx factor-like substance liberated by store depletion is required. How is it that STIM1 interacts with Orai1 and also with structurally unrelated TRPC channels? And concerning the function of STIM2, how is it that mammals have two STIMs, whereas flies function successfully with one? How does STIM1 (but not STIM2) insert into the plasma membrane? In addition to resolving mechanistic questions, future work may target STIM–channel interactions in the design of new immunosuppressant drugs78,79 or to ameliorate cerebrovascular damage following stroke80. Finally, and again referring to early discoveries relating to its chromosomal localization9,81, it will be of interest to learn if STIM has a role in tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank members of the Cahalan and Parker laboratories at UCI who participated in a Stim/Orai Symposium (SOS), where discussions of the literature were extremely helpful; A. Penna and K. Németh-Cahalan for contributions to figures, and I. Parker, A. Demuro and A. Penna for providing the TIRF microscopy Supplementary Movie.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoth M, Penner R. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature. 1992;355:353–356. doi: 10.1038/355353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis RS, Cahalan MD. Mitogen-induced oscillations of cytosolic Ca2+ and transmembrane Ca2+ current in human leukemic T cells. Cell Regul. 1989;1:99–112. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zweifach A, Lewis RS. Mitogen-regulated Ca2+ current of T lymphocytes is activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6295–6299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oritani K, Kincade PW. Identification of stromal cell products that interact with pre-B cells. J. Cell Biol. 1996;134:771–782. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams RT, et al. Identification and characterization of the STIM (stromal interaction molecule) gene family: coding for a novel class of transmembrane proteins. Biochem.J. 2001;357:673–685. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai X. Molecular evolution and functional divergence of the Ca2+ sensor protein in store-operated Ca2+ entry: stromal interaction molecule. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker NJ, Begley CG, Smith PJ, Fox RM. Molecular cloning of a novel human gene (D11S4896E) at chromosomal region 11p15.5. Genomics. 1996;37:253–256. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabbioni S, Barbanti-Brodano G, Croce CM, Negrini M. GOK: a gene at 11p15 involved in rhabdomyosarcoma and rhabdoid tumor development. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4493–4497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manji SS, et al. STIM1: a novel phosphoprotein located at the cell surface. Biochim.Biophys. Acta. 2000;1481:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RT, et al. Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), a transmembrane protein with growth suppressor activity, contains an extracellular SAM domain modified by Nlinked glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1596:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(02)00211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liou J, et al. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+ store depletion-triggered Ca2+influx. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roos J, et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+channel function. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeromin AV, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. A store-operated calcium channel in Drosophila S2 cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2004;123:167–182. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soboloff J, et al. STIM2 is an inhibitor of STIM1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ Entry. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1465–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandman O, Liou J, Park WS, Meyer T. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell. 2007;131:1327–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feske S, et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vig M, et al. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312:1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang SL, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca2+ influx identifies genes that regulate Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercer JC, et al. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:24979–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604589200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peinelt C, et al. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1) Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:771–773. doi: 10.1038/ncb1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soboloff J, et al. Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store-operated calcium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:20661–20665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prakriya M, et al. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vig M, et al. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:2073–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeromin AV, et al. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang SL, et al. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ames JB, Ikura M. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) via the EF-SAM region: An initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35855–35862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba Y, et al. Coupling of STIM1 to store-operated Ca2+ entry through its constitutive and inducible movement in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16704–16709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608358103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dziadek MA, Johnstone LS. Biochemical properties and cellular localisation of STIM proteins. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penna A, et al. The CRAC channel consists of a tetramer formed by Stim-induced dimerization of Orai dimers. Nature. 2008;456:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji W, et al. Functional stoichiometry of the unitary calcium-release-activated calcium channel. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:13668–13673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806499105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liou J, Fivaz M, Inoue T, Meyer T. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9301–9306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702866104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muik M, et al. Dynamic coupling of the putative coiled-coil domain of ORAI1 with STIM1 mediates ORAI1 channel activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:8014–8022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Ikura M. Stromal Interaction Molecule (STIM) 1 and STIM2 calcium sensing regions exhibit distinct unfolding and oligomerization kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:728–732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ikura M. Structural and mechanistic insights into STIM1-mediated initiation of store-operated calcium entry. Cell. 2008;135:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luik RM, Wang B, Prakriya M, Wu MM, Lewis RS. Oligomerization of STIM1 couples ER calcium depletion to CRAC channel activation. Nature. 2008;454:538–542. doi: 10.1038/nature07065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM, Lewis RS. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:803–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Ca2+-store-dependent and -independent reversal of Stim1 localization and function. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:762–772. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varnai P, Toth B, Toth DJ, Hunyady L, Balla T. Visualization and manipulation of plasma membrane-endoplasmic reticulum contact sites indicates the presence of additional molecular components within the STIM1-Orai1 Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29678–29690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamarina NA, Kuznetsov A, Philipson LH. Reversible translocation of EYFPtagged STIM1 is coupled to calcium influx in insulin secreting β-cells. Cell Calcium. 2008;44:533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malli R, Naghdi S, Romanin C, Graier WF. Cytosolic Ca2+ prevents the subplasmalemmal clustering of STIM1: an intrinsic mechanism to avoid Ca2+ overload. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3133–3139. doi: 10.1242/jcs.034496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calloway N, Vig M, Kinet JP, Holowka D, Baird B. Molecular clustering of STIM1 with Orai1/CRACM1 at the plasma membrane depends dynamically on depletion of Ca2+ stores and on electrostatic interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:389–399. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grigoriev I, et al. STIM1 is a MT plus end-tracking protein involved in remodeling of the ER. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smyth JT, DeHaven WI, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Role of the microtubule cytoskeleton in the function of the store-operated Ca2+ channel activator STIM1. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:3762–3771. doi: 10.1242/jcs.015735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alicia S, Angelica Z, Carlos S, Alfonso S, Vaca L. STIM1 converts TRPC1 from a receptor-operated to a store-operated channel: Moving TRPC1 in and out of lipid rafts. Cell Calcium. 2008;44:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pani B, et al. Lipid rafts determine clustering of STIM1 in endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions and regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) J.Biol. Chem. 2008;283:17333–17340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800107200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oka T, Hori M, Ozaki H. Microtubule disruption suppresses allergic response through the inhibition of calcium influx in the mast cell degranulation pathway. J.Immunol. 2005;174:4584–4589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakowski D, Glitsch MD, Parekh AB. An examination of the secretion-like coupling model for the activation of the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current I(CRAC) in RBL-1 cells. J. Physiol. 2001;532:55–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0055g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luik RM, Wu MM, Buchanan J, Lewis RS. The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu P, et al. Aggregation of STIM1 underneath the plasma membrane induces clustering of Orai1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;350:969–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lioudyno MI, et al. Orai1 and STIM1 move to the immunological synapse and are up-regulated during T cell activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706122105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barr VA, et al. Dynamic movement of the calcium sensor STIM1 and the calcium channel Orai1 in activated T-cells: puncta and distal caps. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:2802–2817. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lis A, et al. CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are store-operated Ca2+ channels with distinct functional properties. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:794–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Putney JW., Jr Calcium inhibition and calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:17548–17556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Navarro-Borelly L, et al. STIM1-Orai1 interactions and Orai1 conformational changes revealed by live-cell FRET microscopy. J. Physiol. 2008;586:5383–5401. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang GN, et al. STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC, I(crac) and TRPC1 channels. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/ncb1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Huang GN, Worley PF, Muallem S. STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels to determine their function as store-operated channels. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:636–645. doi: 10.1038/ncb1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang SL, et al. Store-dependent and -independent modes regulating Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity of human Orai1 and Orai3. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:17662–17671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801536200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muik M, et al. A cytosolic homomerization and a modulatory domain within STIM1 C-terminus determine coupling to ORAI1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:8421–8426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800229200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park CY, et al. STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell. 2009;136:876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan JP, et al. SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nature Cell Biol. 2009;11:337–343. doi: 10.1038/ncb1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zweifach A, Lewis RS. Rapid inactivation of depletion-activated calcium current (ICRAC) due to local calcium feedback. J. Gen. Physiol. 1995;105:209–226. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gwack Y, et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J. Biol.Chem. 2007;282:16232–16243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Orai1 subunit stoichiometry of the mammalian CRAC channel pore. J. Physiol. 2008;586:419–425. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng KT, Liu X, Ong HL, Ambudkar IS. Functional requirement for Orai1 in store-operated TRPC1-STIM1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:12935–12940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jardin I, Lopez JJ, Salido GM, Rosado JA. Orai1 mediates the interaction between STIM1 and hTRPC1 and regulates the mode of activation of hTRPC1-forming Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:25296–25304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim MS, et al. Native store-operated Ca2+ influx requires the channel function of Orai1 and TRPC1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:9733–9741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808097200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liao Y, et al. Functional interactions among Orai1, TRPCs, and STIM1 suggest a STIM-regulated heteromeric Orai/TRPC model for SOCE/Icrac channels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.USA. 2008;105:2895–2900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712288105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma HT, et al. Canonical transient receptor potential 5 channel in conjunction with Orai1 and STIM1 allows Sr2+ entry, optimal influx of Ca2+, and egranulation in a rat mast cell line. J. Immunol. 2008;180:2233–2239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ong HL, et al. Dynamic assembly of TRPC1 STIM1 Orai1 ternary complex is involved in store-operated calcium influx. Evidence for similarities in store-operated and calcium release-activated calcium channel components. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:9105–9116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608942200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeng W, et al. STIM1 gates TRPC channels, but not Orai1, by electrostatic interaction. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liao Y, et al. Orai proteins interact with TRPC channels and confer responsiveness to store depletion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4682–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liao Y, et al. A role for Orai in TRPC-mediated Ca2+ entry suggests that a TRPC:Orai complex may mediate store and receptor operated Ca2+ entry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.USA. 2009;106:3202–3206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813346106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bolotina VM. Orai, STIM1 and iPLA2β: a view from a different perspective. J. Physiol. 2008;586:3035–3042. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Csutora P, et al. Novel Role for STIM1 as a Trigger for Calcium Influx Factor Production. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:14524–14531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709575200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Randriamampita C, Tsien RY. Emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores releases a novel small messenger that stimulates Ca2+ influx. Nature. 1993;364:809–814. doi: 10.1038/364809a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Redondo PC, Jardin I, Lopez JJ, Salido GM, Rosado JA. Intracellular Ca2+ store depletion induces the formation of macromolecular complexes involving hTRPC1,hTRPC6, the type II IP(3) receptor and SERCA3 in human platelets. Biochim. Biophys.Acta. 2008;1783:1163–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cahalan MD, et al. Molecular basis of the CRAC channel. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oh-hora M, Rao A. Calcium signaling in lymphocytes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008;20:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Varga-Szabo D, et al. The calcium sensor STIM1 is an essential mediator of arterial thrombosis and ischemic brain infarction. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1583–1591. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sabbioni S, et al. Exon structure and promoter identification of STIM1 (alias GOK), a human gene causing growth arrest of the human tumor cell lines G401 and RD.Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1999;86:214–218. doi: 10.1159/000015341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hewavitharana T, et al. Location and function of STIM1 in the activation of Ca2+ entry signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26252–26262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802239200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lopez JJ, Salido GM, Pariente JA, Rosado JA. Interaction of STIM1 with endogenously expressed human canonical TRP1 upon depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:28254–28264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hauser CT, Tsien RY. A hexahistidine-Zn2+-dye label reveals STIM1 surface exposure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3693–3697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611713104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. STIM1 regulates Ca2+ entry via arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels without store depletion or translocation to the plasma membrane. J. Physiol. 2007;579:703–715. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Both Orai1 and Orai3 are essential components of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels. J. Physiol. 2008;586:185–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baba Y, et al. Essential function for the calcium sensor STIM1 in mast cell activation and anaphylactic responses. Nature Immunol. 2008;9:81–88. doi: 10.1038/ni1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oh-Hora M, et al. Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nature Immunol. 2008;9:432–443. doi: 10.1038/ni1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stiber J, et al. STIM1 signalling controls store-operated calcium entry required for development and contractile function in skeletal muscle. Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:688–697. doi: 10.1038/ncb1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Braun A, et al. STIM1 is essential for Fcγ receptor activation and autoimmune inflammation. Blood. 2009;113:1097–1104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grosse J, et al. An EF hand mutation in Stim1 causes premature platelet activation and bleeding in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3540–3550. doi: 10.1172/JCI32312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Picard C, et al. STIM1 mutation associated with a syndrome of immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1971–1980. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wedel B, Boyles RR, Putney JW, Jr, Bird GS. Role of the store-operated calcium entry proteins Stim1 and Orai1 in muscarinic cholinergic receptor-stimulated calcium oscillations in human embryonic kidney cells. J. Physiol. 2007;579:679–689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jousset H, Frieden M, Demaurex N. STIM1 knockdown reveals that store-operated Ca2+ channels located close to sarco/endoplasmic Ca2+ ATPases (SERCA) pumps silently refill the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:11456–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Role of STIM1 in regulation of store-operated Ca2+ influx in pheochromocytoma cells. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2009;29:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s10571-008-9311-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang S, Zhang JJ, Huang XY. Orai1 and STIM1 are critical for breast tumor cell migration and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aubart FC, et al. RNA interference targeting STIM1 suppresses vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in the rat. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:455–462. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dietrich A, et al. Pressure-induced and store-operated cation influx in vascular smooth muscle cells is independent of TRPC1. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455:465–477. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guo RW, et al. An essential role for stromal interaction molecule 1 in neointima formation following arterial injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;81:660–668. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP. A key role for STIM1 in store operated calcium channel activation in airway smooth muscle. Respir. Res. 2006;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Takahashi Y, et al. Functional role of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;361:934–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jones BF, Boyles RR, Hwang SY, Bird GS, Putney JW. Calcium influx mechanisms underlying calcium oscillations in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008;48:1273–1281. doi: 10.1002/hep.22461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.El Boustany C, et al. Capacitative calcium entry and transient receptor potential canonical 6 expression control human hepatoma cell proliferation. Hepatology. 2008;47:2068–2077. doi: 10.1002/hep.22263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aromataris EC, Castro J, Rychkov GY, Barritt GJ. Store-operated Ca2+ channels and Stromal Interaction Molecule 1 (STIM1) are targets for the actions of bile acids on liver cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:874–885. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Litjens T, et al. Phospholipase C-γ1 is required for the activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels in liver cells. Biochem. J. 2007;405:269–276. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tolhurst G, et al. Expression profiling and electrophysiological studies suggest a major role for Orai1 in the store-operated Ca2+ influx pathway of platelets and megakaryocytes. Platelets. 2008;19:308–313. doi: 10.1080/09537100801935710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Berra-Romani R, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Pulina MV, Golovina VA. Ca2+ handling is altered when arterial myocytes progress from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype in culture. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2008;295:C779–C790. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00173.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lu W, Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Differences in STIM1 and TRPC expression in proximal and distal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle are associated with differences in Ca2+ responses to hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008;295:L104–L113. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00058.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.