Abstract

This study utilized participant feedback to qualitatively evaluate an intervention (ACTIVE) that utilized videophone technology to include patients and/or their family caregivers in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings. Data were generated during individual interviews with hospice staff members and family caregivers who participated in ACTIVE. Modified grounded theory procedures served as the primary analysis strategy. Results indicated that ACTIVE enhanced team functioning in terms of context, structure, processes, and outcomes. Participants discussed challenges and offered corresponding recommendations to make the intervention more efficient and effective. Data supported the ACTIVE intervention as a way for hospice providers to more fully realize their goal of maximum patient and family participation in care planning.

Keywords: hospice care, telemedicine, patient care team, family, patients, caregivers

Introduction

Background

In 2007, approximately 1.4 million terminally ill individuals and their family members received services from a hospice agency in the United States (1). The goal of hospice care is to ensure that terminally ill patients experience a death that is as natural, dignified, and comfortable as possible. Professional hospice care is provided by a wide range of interdisciplinary providers, including nurses, social workers, chaplains, home health aides, bereavement representatives, and physicians (2). In addition, as with most community-based care, family or informal caregivers provide the majority of the individual care needed by terminally ill patients (3).

Most U.S. hospice patients (83.6%) are covered by the Medicare Hospice Benefit (1), which requires that hospice services be provided according to a plan of care developed by an interdisciplinary team (IDT) comprised of at least a doctor of medicine or osteopathy, a registered nurse, a social worker, and a pastoral or other counselor (4). Federal regulations require that the hospice plan of care be reviewed and updated during routine IDT meetings held no less frequently than every 15 calendar days (5). Although the hospice philosophy of care considers patients and families to be central members of the hospice team, their participation in IDT meetings is rare due to geographic barriers and caregiver time constraints (6, 7). This lack of involvement limits the abilities of patients and their loved ones to ask questions, voice concerns, and communicate and collaborate with all members of the team, particularly since not all hospice team members regularly conduct patient visits.

Conceptual Model

This study is informed by a conceptual model (8) inspired by Saltz and Schaefer's (9) work on health care teams. The model suggests that family involvement on health care teams may significantly impact team functioning and, ultimately, health care outcomes. Effective team functioning is conceptualized as being comprised of four interrelated, essential components: context, structure, process, and outcomes. The context within which a health care team operates consists of the culture of the wider organization coupled with the relationship of the team to its environment. Team structure refers to the composition of the group in terms of individual members and the properties of the team as a collective group. Team processes include leadership, information sharing and communication, problem solving and decision making, and conflict resolution and feedback; however, Saltz and Schaefer (9) do not claim that this is an exhaustive list. Finally, outcomes refer to the results and consequences of the team's efforts.

The ACTIVE Intervention

Patient and family participation in hospice IDT meetings is both consistent with the hospice philosophy of care and supported by Saltz and Schaefer's (9) theoretical model. Yet, significant barriers exist to fully involving patients and their family members in IDT meetings (6,7). The ACTIVE (Assessing Caregivers for Team Intervention through Videophone Encounters) intervention was designed to overcome these barriers by allowing patients and/or their informal caregivers to participate in meetings from their own homes using commercially available videophone technology. This represents both a practical application and an extension of the original Saltz and Schaefer (9) model. By eliminating logistical barriers, ACTIVE was designed to provide the context for patient and family participation in hospice IDT meetings. Principles inherent within hospice provide the team with a supportive structure that acknowledges patient/family roles as active team members. Finally, team processes are modified, resulting in altered outcomes for hospice patients and families.

Intervention procedures

Following family enrollment in the ACTIVE intervention, research staff installed a videophone unit in the homes of participating families, connecting them to the hospice office using a standard telephone line. The hospice office was equipped with compatible videophone technology that could be viewed on a large television screen, thereby permitting numerous members of the hospice IDT to view the participant simultaneously. The intervention was designed primarily for family caregivers; patients could participate as their health condition(s) allowed. Figure 1 illustrates the technology used in this study.

Figure 1.

The videophone used by caregivers was the Beamer Videophone Station (Vialta, Inc., CA) which operates over regular telephone lines (depicted on the left side). Hospice teams used the Beamer TV Videophone Station to display the image on a large TV screen (depicted on the right side).

Study Aims

The overall aim of this study was to evaluate ACTIVE using feedback from the families and staff members who participated in the intervention. Specifically, the study sought to determine which aspects of the ACTIVE intervention participants viewed as beneficial, which aspects were perceived as challenging, and what recommendations participants provided for future ACTIVE interventions.

Methods

Procedures

Data collection related to the present analysis occurred at the conclusion of the ACTIVE intervention. Hospice staff members and informal caregivers participated in semi-structured interviews during which they were asked a series of both closed- and open-ended questions about their experiences as participants in the intervention. An initial interview guide was developed based upon the core research questions for the study. To ensure its face validity, the interview guide was reviewed by a Scientific Advisory Board comprised of hospice experts prior to implementation. Informal caregivers participated in interviews 14-21 days following the death of the patient for whom they provided care and/or the conclusion of the study. All staff interviews were conducted during the final month of the intervention. Based upon study participants' preferences, interviews were either conducted face-to-face or by telephone. All interviews were audio taped and transcribed verbatim for purposes of analysis. Researchers verified transcriptions by simultaneously listening to audio recordings of the interviews and reading the transcribed content. To ensure confidentiality of study data, all identifying information was removed from interview transcripts. Data were tied to participants through a coding key that included only non-identifying information necessary to track participant characteristics.

Protection of Human Subjects

Protection of human subjects was accomplished by strict adherence to the study protocol approved by the sponsoring institution's Institutional Review Board. There was minimal risk for human subjects participating in the study, as their involvement was limited to participating in biweekly team meetings during the ACTIVE intervention and discussing their experiences during a post-intervention interview. However, it was possible that an in-depth discussion of their involvement caring for a terminally ill loved one could result in emotional distress for some caregivers. Given that all caregivers were receiving services from a hospice agency during the ACTIVE intervention and at the time of the interviews (including bereavement support provided for a full year after the patient's death), the researchers were able to refer participating caregivers to hospice staff members including social workers, chaplains, and bereavement coordinators, if they felt those services would be beneficial.

Sample

Interview participants consisted of staff members (n=25) and informal caregivers (n=17) who had been involved in the ACTIVE intervention. Interviewees were selected according to a purposive sampling strategy designed to ensure adequate representation of all key disciplines on the hospice IDT, along with a diverse group of caregivers. All study participants were associated with one of two Midwestern hospices that participated in the ACTIVE project. Each hospice operated two teams that served different regions of the state, resulting in a total of four participating teams. Table 1 summarizes participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| (N = 42) | |

|---|---|

| Staff characteristics (n = 25) | |

| Gender | |

| Women | 21 |

| Men | 4 |

| IDT Role | |

| Registered nurse | 8 |

| Social worker | 3 |

| Spiritual care provider | 4 |

| Home health aide | 1 |

| Bereavement representative | 2 |

| Physician/Medical director | 2 |

| Administrator/Supervisor | 4 |

| Volunteer coordinator | 1 |

| Caregiver characteristics (n = 17): | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 62.3 (13.5) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 13 |

| Men | 4 |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Spouse/partner | 7 |

| Adult child | 5 |

| Sibling | 2 |

| Parent | 1 |

| Other | 2 |

Data Analysis

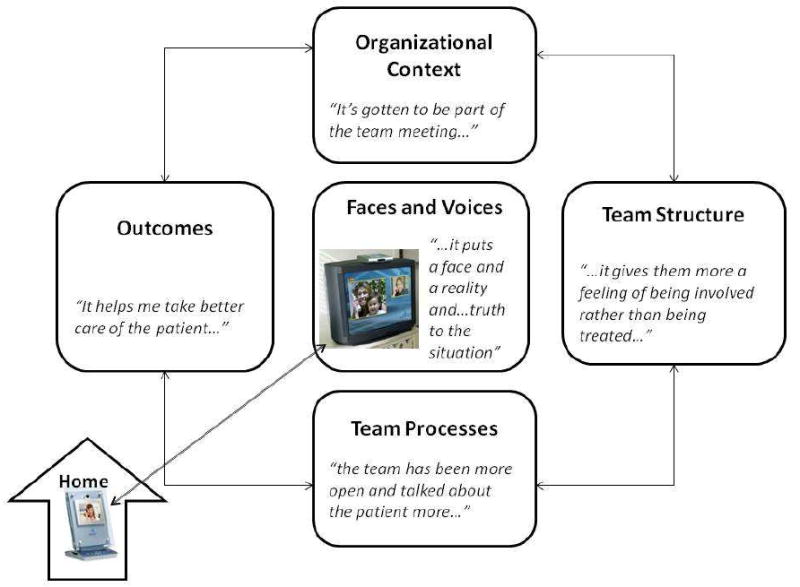

A modified grounded theory approach as explicated by Strauss and Corbin (10) directed data analysis. Traditional grounded theory procedures were adapted to allow researchers to consider emerging concepts within the framework of team functioning provided by Saltz and Schaefer (9). Strauss and Corbin endorse this approach, provided it is used in an effort to further develop existing theory (10), as is the case with the present study. QSR NVivo 8 software was utilized to organize and manage data analysis tasks. Two members of the research team (DPO, KTW) engaged in descriptive coding during which detailed labels were applied to segments of data based upon their content and/or meaning. Coding was compared both within and among all interviews, leading to the generation of themes that provided a more in-depth view of the perceived benefits, challenges, and recommendations associated with the intervention. Finally, relationships among the themes were explored and considered within the context of Saltz and Schaefer's model of effective team functioning (9), resulting in a revised model (Figure 2) that illustrates participants' experiences in all aspects of the ACTIVE intervention.

Figure 2.

Results

Data from staff members and family caregivers were combined and then organized according to the following themes: faces and voices, context, structure, processes, and outcomes. It is important to note that these themes closely mirror the four components of effective team functioning as explicated by Saltz and Schaefer (9), with the exception of the faces and voices theme. Benefits, challenges, and participant recommendations associated with each theme will be addressed below.

Faces and Voices

Family members discussed how audio and visual communication with the hospice employees gave them “faces” and “voices” in meetings – both literally and figuratively. Caregivers reported that their participation in IDT meetings resulted in them feeling “included” and “more involved in the actual treatment.” When asked if she felt a part of the decision making process, one caregiver replied, “I know I was.” Numerous hospice employees described how powerful it was to see the patients and families whose care was being discussed, echoing the sentiment of a chaplain who said that the visual element “just makes it seem more like a person.” Staff members indicated that the overall effect of having families' faces and voices in team meetings was that their situations became personalized. Many staff members stressed that ACTIVE made the lives of patients and their families seem “more real.” A medical director commented, “I think the most important thing is that it puts a face and a reality and … truth to the situation that you just really don't have otherwise.”

One caregiver described how the videophone encounters affected her. She said, “It's almost like they bring the hug.” She went on to elaborate,

You're isolated in your own home and family members don't even come by. And it's like you have that hand on your shoulder with the phones and the faces … and it made a big difference.

Despite the benefits of seeing faces and hearing voices, both caregivers and staff members noted that improvements in the overall technological quality were needed. Staff members typically indicated that the sound quality was good at the office site, but some patients and caregivers noted that they struggled to hear the team members from their home videophone unit. Complaints about the videophone picture were more common. Some participants described the picture as “fuzzy” and/or “grainy” at times or commented about the slight delay between the sound and the picture. While team members at the hospice office enjoyed a large, “up close” view of the family members, many caregivers suggested that a larger screen on their home units would have been helpful, especially for families in which many people contributed to providing care for the patient. That way, they explained, additional caregivers would have been able to participate. Caregivers also noted that the limited scope of the videophone camera and the distance the camera was placed from staff members often made it difficult for them to see all the team members. Additionally, staff members sometimes found that establishing a connection between the home and office units took longer than they would have liked, adding to their already lengthy team meetings.

Context

Participants discussed the context of team meetings, referring to the broader culture, environment, and atmosphere influencing the IDT and its members. A chaplain described how the agency culture adapted to the once-new ACTIVE intervention as it became incorporated into routine care: “It's gotten to be part of the team meeting, and we … focus our meeting around [it].” Caregivers talked about how the context of their daily lives impacted their participation in team meetings, particularly with regard to caregiving tasks. Family members praised the intervention because it eliminated the need for them to leave home and drive to the agency office in order to participate. Some caregivers described how leaving the house was impossible due to caregiving responsibilities. Others said that they viewed participating in IDT meetings from home as more of a convenience. One caregiver noted, “… one of the advantages is it saves me a trip into town, but I still get to see everybody involved in [the patient's] case.”

Some staff members discussed challenges associated with contextual factors, especially with regard to time. In fact, the most commonly reported challenge associated with the ACTIVE intervention from the perspective of staff members was the amount of additional time that patient and family participation added to IDT meetings. A nurse supervisor noted that ACTIVE “… makes team meetings last longer, and we all know that we don't want to be in meetings any longer than we have to.” Although team members reported that they recognized the need for time management during IDT meetings, some said they were faced with a dilemma when forced to decide between stopping a conversation with a caregiver and allowing the discussion to last for a long period of time. A nurse noted, “Some [caregivers] talk too long … they don't realize that this is a meeting and we have other patients that we have to talk about … and that is a challenge because you don't want to take [their time] away from them either.”

Caregivers also mentioned challenges related to the contextual factor of time limitations but, unlike staff members, they discussed the duration of the overall intervention itself rather than individual meetings. Many shared their frustration that hospice services, including the ACTIVE intervention, had been initiated so late in their loved one's illness. One of the most frequently voiced caregiver complaints was that they participated in too few team meetings as a result of their loved one's short length of time on hospice. One caregiver noted, “We only had one team meeting before [the patient] died.” The husband of a hospice patient voiced disappointment that “we did not get to use it as much as we intended to … because my wife passed away sooner than we thought.”

Structure

Participants indicated that the ACTIVE intervention changed the structure of hospice teams because it changed the composition of team meetings by including caregivers. In turn, participants reported, the identity of the group was changed. However, many staff members explained that the idea that patients and families were central figures on the hospice team was not new to them. In fact, numerous staff members indicated that maximum patient and family involvement in care had been a longstanding ideal in their agencies. Yet, many reported that a disconnect existed between the stated ideal and reality as they experienced it. One home health aide explained that before her participation in the ACTIVE intervention,

… my mind was narrowed to a point where I thought that the “team” was the team that was here [in the agency office], not realizing and accepting that the team also included the family and patients. Even though I could say it … I didn't feel it.

A social worker with years of experience in a variety of different health care settings expanded on this view. She stated, “We always talk about interactive methods in medicine, and [ACTIVE] is probably my first real example of it.”

While most staff members welcomed the restructuring of their team to include patients and families, some staff members expressed ambivalence about the change. A nurse mentioned being caught off guard when one caregiver in particular shared information with the medical director that she was unaware of,

She likes to bring stuff up in team meetings that she doesn't tell anybody else about … about [the patient's] falls … and about him not sleeping or some of his pain issues …. Before team, she wouldn't say anything, but she would tell [the medical director] in the meeting.

Processes

Staff and family members discussed how ACTIVE impacted the activities and processes that occurred during team meetings, noting specific changes to relationships, communication, and collaboration. When discussing relationships between staff members and families, a chaplain noted, “I think the fact that they can actually see us on those phones … makes them feel more comfortable.” She explained that having families participate in team meetings also increased the “trust factor” between staff members and families. A medical director noted that ACTIVE significantly enhanced his relationships with patients and families because, without the intervention, he might never have met them:

… a given patient that you never communicate with directly except by phone … on a rare basis, might not even know who you are, the kind of person you are as a provider. This way they meet you, they interact with you, they know what they are getting in terms of physician oversight and management of their care ….

Other providers spoke about ACTIVE as a way to “develop rapport” and “build connection” with patients and families.

In addition to strengthening relationships, participants indicated that team meetings became an opportunity for direct communication between the IDT and patients and families. Caregivers commented that having all the team members together in one setting allowed them to resolve multiple issues at once without making numerous phone calls to different members of the hospice staff. Participants noted that communication and decision making was expedited, as one caregiver described,

There was no … asking one person and then them talking to the team and finding out if we could do what we wanted to do …. We could find out immediately, so there was no lag as far as the decision making process.

A social worker discussed the empowering effect of caregivers having direct access to all members of the hospice team: “… it kind of takes some of that feeling of intimidation away when they feel that they can just address the doctor and ask questions before anyone else.” Nurses tended to express agreement. One stated, “It's been nice to have the doctor hear from the family members who are there one-on-one with the patient. That way you are not relaying information second hand.” Another nurse stated that she believed ACTIVE may have resulted in caregivers sharing more information than they would have otherwise because, “there are a lot of patients' families that will tell the doctor some things that they won't to everybody else.”

Many participants discussed how direct communication resulted in everyone having a better understanding of “what's going on.” Caregivers provided numerous example of this, explaining how the intervention resulted in them having a better understanding of the plan of care, knowing who was doing what for the patient and when, and knowing what to expect in the future. One caregiver mentioned that participating in IDT meetings allowed her to have a better understanding of her husband's “timeline,” which was the language she used to describe his dying trajectory. One program director noted that patients and caregivers were better able to direct care when they participated in IDT meetings: “… they have much more ownership of the plan of care and what's going on … they understand it.” Staff members also stated that ACTIVE allowed them to have a better idea about “what's going on,” as caregivers provided real-time updates during team meetings. A staff member described how ACTIVE allowed her to “take care of questions and problems [patients and caregivers] have right then … rather than having to wait.”

Participants noted that direct communication was not without its challenges. Some staff members voiced concerns about how the presence of patients and caregivers made it difficult to communicate about sensitive topics. One staff member explained, “… there may be things that we feel like we need to discuss without the family, and that can be kind of awkward ….” Other staff members disagreed, indicating that, “I think we shouldn't [ever] say very many things that we can't say in front of the patient or their loved one.”

ACTIVE participants also stated that including families in IDT discussions resulted in more collaboration during meetings. Caregivers described how they appreciated receiving feedback from multiple disciplines, as the wife of a hospice patient described: “The nurses that were coming out here were fine … but it was just nice to get other people's input, too.” Another caregiver stated that she was impressed to learn that “a whole team of people” worked together to provide care for her husband. Staff members reported that more collaboration occurred among themselves during IDT meetings in which families participated. A chaplain noted that, “I think actually the team has been more open and talked about the patient a little bit more. So I think it's been good for the team as well.” One team's volunteer coordinator discussed interdisciplinary learning as a benefit of ACTIVE team meetings: “It's really nice to observe how other members of our team interact with [caregivers]. I think we can learn from each other.” One team member summarized the collaborative benefit of ACTIVE in the following way:

It gives [families] more of a feeling of being involved than being treated …. We know what the patient and family want, and we also know what we are capable of doing, and when they mix it together, it makes a team effort.

Finally, several participants recommended that future ACTIVE interventions introduce more structure around the team communication. One nurse hoped that future team meetings with families would be “more focused.” She continued, “I think it could be organized … maybe you have some trigger questions … in a more organized format.” Another nurse asked for a “guideline” to direct patient/family discussions.

Outcomes

Many participants stated that they believed that the ACTIVE intervention resulted in improved outcomes for patients and families, referring to the services and care that were ultimately provided as a result of team meetings. A bereavement coordinator noted that ACTIVE gave caregivers a platform from which to be heard and often resulted in some caregivers being able to “hang in there a heck of a lot longer” than they might have otherwise. A chaplain said that ACTIVE made her team “function more responsively” to the needs of the family. A medical director noted that patient care improved with family participation in IDT meetings: “… it helps me take better care of the patient. I know what to do better when I can talk to them and see them.” A supervisory nurse explained that team meetings were typically more productive when families participated: “… it helped to keep the staff focused on the needs of the patient.”

Three participants (two staff members and one caregiver) reported that they saw little benefit in the intervention. One staff member indicated that ACTIVE was “redundant” because “… nurse visits can accomplish the same thing.” One nurse explained that, in the absence of additional team training, ACTIVE might not result in many tangible outcomes for patients and families. She described how the intervention was limited “… particularly because of the staff. I think a lot of the staff … doesn't know how to handle an interview.” One caregiver stated, “It just didn't seem to contribute that much.” She went on to explain that she communicated very well with staff members outside of team meetings and was typically fully aware of what was going on before IDT meetings were held.

Discussion

This evaluation provides valuable participant feedback related to the ACTIVE intervention in terms of both benefits and challenges. In particular, it sheds light on the need for additional training for both staff members and caregivers. Future ACTIVE interventions will incorporate additional training elements, particularly with regard to communication. Staff members can benefit from education about how to better involve patients and families in discussions about their care; further research is needed to determine the best way to achieve that goal. Family caregivers will become more effective team members if they have a better understanding of the central purpose of team meetings (i.e., to discuss patient care) and are able to communicate in a meaningful yet succinct manner. Additionally, a comprehensive assessment of hospice caregivers is needed that will assist in identifying which families will benefit most from the ACTIVE intervention, as the context of IDT meetings does not presently support 100% participation due to time constraints placed on hospice providers.

Training related to videophone technology is also in order. While most family members reported they found the technology easy to use, many voiced concerns about problems with the technical quality in terms of the visual and/or audio elements. Some technical quality issues will only be addressed as the technology improves or as more homes become equipped to handle videophone technology that utilizes a broadband connection and allows for better video quality versus a standard telephone connection such as the one used in this study. However, even with existing connections, technical quality will be improved if staff members are trained to focus the camera squarely on the individual(s) speaking, allowing families to receive meaningful non-verbal messages. Careful placement of lighting in the agency office will improve the picture seen by caregivers. Finally, staff members can be trained to speak in a way that increases the likelihood of caregivers hearing them. Speaking in short phrases with frequent pauses and reducing or eliminating interruptions or “talking over” one another is strongly advised.

Providers can more fully realize their stated goal of maximum patient and family participation in care planning through the use of widely available technology. Implementation of the ACTIVE intervention represents an important move in that direction by involving patients and their caregivers in IDT meetings, giving them direct access to all members of the hospice team, enhancing team processes, and improving patient outcomes as perceived by their direct caregivers and hospice professionals. Positive feedback from staff members and families involved in the intervention provides further support for ACTIVE's incorporation into routine hospice care.

Finally, this evaluation supports the use and further refinement of Saltz and Schaefer's (9) model of family integration into interdisciplinary health care teams. The model provided this study with an initial framework of key components common to the functioning of effective teams: context, structure, process, and outcomes. Themes describing benefits and/or challenges associated with the ACTIVE intervention emerged that affected each of these four components. However, researchers studying videophone-mediated team meetings should consider the impact of the audio and visual components (discussed by study participants as “faces” and “voices”) that make this type of group interaction unique.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute R21 CA120179 Patient and Family Participation in Hospice Interdisciplinary Teams.

Contributor Information

Debra Oliver Parker, University of Missouri, Family & Community Medicine.

Karla Washington, University of Louisville, Kent School of Social Work.

Elaine Wittenberg-Lyles, University of North Texas, Communication Studies.

George Demiris, University of Washington, School of Nursing.

Davina Porock, University of Nottingham, School of Nursing.

References

- 1.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO facts and figures: Hospice care in America. 2008 [November 14, 2008]; Available from: www.nhpco.org/files/public/Statistics_Research/NHPCO_facts-and-figures_2008.pdf.

- 2.Wittenberg-Lyles EM, Oliver Parker D, Demiris G, Courtney K. Assessing the nature and process of hospice interdisciplinary team meetings. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2007;9(1):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: The experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Mar 21;132(6):451–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-6-200003210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Washington, DC: U.S: Government Printing Office via GPO Access; 2007. Code of Federal Regulations. 42CFR418. [January 24, 2008]; Available from: www.gpoaccess.gov/cfr/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: Hospice Conditions of Participation. 2008 42 CFR § 418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver Parker D, Porock D, Demiris G, Courtney K. Patient and family involvement in hospice interdisciplinary teams. Journal of Palliative Care. 2005;21(4):270–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver Parker D, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K, Sehrawat S. Social work role in hospice pain management: A national survey. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Careunder review. doi: 10.1080/15524250903173900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver Parker D, Demiris G, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Porock D. The use of videophones for patient and family participation in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings: A promising approach. European Journal of Cancer Care. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01142.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saltz CC, Schaefer T. Interdisciplinary teams in health care: Integration of family caregivers. Social Work in Health Care. 1996;22(3):59–70. doi: 10.1300/J010v22n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]