Abstract

Rett syndrome (RTT) is an X chromosome-linked neurodevelopmental disorder associated with the characteristic neuropathology of dendritic spines common in diseases presenting with mental retardation (MR). Here, we present the first quantitative analyses of dendritic spine density in postmortem brain tissue from female RTT individuals, which revealed that hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons have lower spine density than age-matched non-MR female control individuals. The majority of RTT individuals carry mutations in MECP2, the gene coding for a methylated DNA-binding transcriptional regulator. While altered synaptic transmission and plasticity has been demonstrated in Mecp2-deficient mouse models of RTT, observations regarding dendritic spine density and morphology have produced varied results. We investigated the consequences of MeCP2 dysfunction on dendritic spine structure by overexpressing (∼twofold) MeCP2-GFP constructs encoding either the wildtype (WT) protein, or missense mutations commonly found in RTT individuals. Pyramidal neurons within hippocampal slice cultures transfected with either WT or mutant MECP2 (either R106W or T158M) showed a significant reduction in total spine density after 48hrs of expression. Interestingly, spine density in neurons expressing WT MECP2 for 96hrs was comparable to that in control neurons, while neurons expressing mutant MECP2 continued to have lower spines density than controls after 96hrs of expression. Knockdown of endogenous Mecp2 with a specific small hairpin interference RNA (shRNA) also reduced dendritic spine density, but only after 96hrs of expression. On the other hand, the consequences of manipulating MeCP2 levels for dendritic complexity in CA3 pyramidal neurons were only minor. Together, these results demonstrate reduced dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal neurons from RTT patients, a distinct dendritic phenotype also found in neurons expressing RTT-associated MECP2 mutations or after shRNA-mediated endogenous Mecp2 knockdown, suggesting that this phenotype represent a cell-autonomous consequence of MeCP2 dysfunction.

Keywords: MeCP2, Rett syndrome, dendrite, dendritic spine, pyramidal neuron, hippocampus, DiOlistics, human postmortem brain

INTRODUCTION

Deficits in dendritic architecture are common in disorders associated with mental retardation (MR), ranging from environmental (e.g. fetal alcohol syndrome) to autosomal (e.g. Down syndrome) and X chromosome-linked forms of MR (e.g. Fragile-X, Rett syndrome; reviewed by Fiala et al., 2002; Kaufmann and Moser, 2000). A series of groundbreaking studies published in the 1970’s established the precedent of abnormalities in dendritic organization in cortical neurons from humans with MR (Huttenlocher, 1970; Huttenlocher, 1974; Marin-Padilla, 1972; Marin-Padilla, 1976). These series of observations consistently described reductions in the density of dendritic spines, the postsynaptic compartment of excitatory synapses (reviewed by Peters et al., 1991). In addition, a prevalence of long and tortuous spines, thought to represent immature synapses, were also commonly observed in MR and combined, these dendritic spine anomalies were referred to as “spine dysgenesis” (Purpura, 1974). Since dendritic development is a process where the formation and maturation of spines are the result of interactions between intrinsic genetic factors and external environment, the study of spine development and maintenance in MR has significant clinical relevance.

Rett syndrome (RTT) is an X chromosome-linked mental retardation that results from sporadic mutations in the gene coding for the methylated DNA-binding transcription factor MeCP2 (Amir et al., 1999; reviewed by Percy, 2001). RTT affects approximately 1:10,000 females worldwide, and prominent symptoms include deceleration of body and head growth rate, hand stereotypies and regression in motor and speech capabilities, irregularities in motor activity and breathing patterns, in addition to cognitive impairments characteristic of an autism-spectrum disorder (reviewed by Percy and Lane, 2005). Although RTT occurs predominantly in females, mutations of MECP2 have also been identified in males, where the phenotypes range from severe encephalopathy, to classic RTT, to nonspecific MR (Couvert et al., 2001; Kankirawatana et al., 2006; Masuyama et al., 2005; Moog et al., 2003). While mutations of MECP2 have been associated with RTT, duplications in the chromosomal region where MECP2 is located were shown to be related to neurological disorders associated with MR, suggesting that MECP2 is a critical dosage-sensitive gene (del Gaudio et al., 2006; Smyk et al., 2008).

Morphological studies in postmortem brain samples from RTT individuals described a characteristic neuropathology, which included decreased neuronal size and increased neuronal density in the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus and the hippocampal formation (Bauman et al., 1995a; Bauman et al., 1995b); decreased dendritic growth in pyramidal neurons of the subiculum and frontal and motor cortices (Armstrong et al., 1995); as well as the characteristic MR-associated spine dysgenesis, observed in pyramidal neurons of the motor cortex with regions of dendrites devoid of spines (Belichenko et al., 1994). The reduction in dendritic area together with the marked decrease in dendritic spine density strongly suggests that impaired synaptic transmission is a likely pathogenic consequence of MECP2 mutations causing RTT. Indeed, the increase in neuronal expression of MECP2/Mecp2 during early brain development suggests the importance of this protein in synapse formation and maintenance (Akbarian et al., 2001; Cassel et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2003; Kaufmann et al., 2005; Mullaney et al., 2004; Shahbazian et al., 2002b). While hippocampal and cortical synaptic dysfunction in Mecp2-based mouse models of RTT has been extensively studied, observations regarding neuronal, dendritic and synaptic pathologies have produced varied results (Asaka et al., 2006; Chao et al., 2007; Dani et al., 2005; Fukuda et al., 2005; Gemelli et al., 2006; Jugloff et al., 2005; Kishi and Macklis, 2004; Moretti et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2006; Smrt et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2006). Here, we present the first quantitative analyses of dendritic spine density in postmortem brain tissue from RTT individuals. To identify the consequences of cell-autonomous MeCP2 dysfunction on the morphology of dendrites and dendritic spines in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, we transfected organotypic slice cultures with either wildtype or RTT-associated MECP2 mutations.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

HUMAN POSTMORTEM BRAIN

All procedures on human postmortem brain samples followed national and international ethics guidelines, and were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). Brain sections containing the hippocampal formation were obtained from individuals diagnosed with RTT, and unaffected (non-MR) individuals served as controls. Post-mortem human tissue was obtained from the Department of Pathology, Baylor College of Medicine, the NICHD Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, and from the Harvard Brain Bank. Table 1 presents all the available information on the individuals whose brains were used in this study. Unfortunately, information about specific MECP2 mutations in Rett syndrome samples is not available from the brain banks.

Table 1.

AVAILABLE INFORMATION OF THE HUMAN BRAIN SAMPLES FOR THE ANALYSES OF DENDRITIC SPINE DENSITY FROM HIPPOCAMPAL PYRAMIDAL NEURONS

| Individual code | Brain bank | Gender | Age in years | Cause of death | Average spine density (spines/10µm) | Total dendritic length (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1284 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 3 | Drowning | 12.26 | 1602.87 |

| 1377 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 5 | Drowning | 7.82 | 641.75 |

| 4638 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 15 | MVA | 10.10 | 777.54 |

| 1571 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 18 | MVA | 10.14 | 1447.34 |

| 1101 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 19 | MVA | 5.30 | 521.08 |

| 4786 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 22 | MVA | 8.18 | 704.34 |

| 1792 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 25 | MVA | 8.45 | 322.41 |

| 1380 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 35 | MVA | 10.40 | 400.76 |

| 4643 (non-MR) | UMB | F | 42 | HASCVD | 9.88 | 1338.74 |

| 6150 (Rett) | HBB | F | 3 | Cardiac Arrest | 4.40 | 610.32 |

| 1194 (Rett) | UMB | F | 5 | Asphyxia | 5.04 | 906.83 |

| 6100 (Rett) | HBB | F | 10 | Unknown | 8.85 | 926.59 |

| 6176 (Rett) | HBB | F | 15 | MI | 5.83 | 636.55 |

| 6355 (Rett) | HBB | F | 16 | Respiratory Failure | 5.77 | 687.61 |

| 1420 (Rett) | UMB | F | 21 | Unknown | 7.50 | 1854.55 |

| 1748 (Rett) | UMB | F | 22 | Unknown | 9.99 | 2163.51 |

| 5741 (Rett) | HBB | F | 25 | Pneumonia | 3.77 | 1073.66 |

| 5478 (Rett) | HBB | F | 42 | Unknown | 3.73 | 416.80 |

| 5763 (Rett) | HBB | F | 42 | Pneumonia | 5.87 | 355.07 |

Formalin-fixed human brain samples were obtained from either the University of Maryland (UMB) or Harvard Brain Bank (HBB). The Table lists all the information provided by the brain banks (ages in years, causes of death, and confidential non-identifier codes). Information about specific MECP2 mutations in Rett syndrome samples was not available from the brain banks. The average spine density and total dendritic length for each individual is presented to provide a sense of the statistical sample analyzed.

For individual 4638 (non-MR), the cause of death resulted from chest injuries sustained in a motor vehicle accident (MVA). For individuals 1571 (non-MR), 1101 (non-MR), 4786 (non-MR), 1792 (non-MR), and 1380 (non-MR) the causes of death resulted from multiple injuries sustained in a MVA. For individual 4643 (non-MR), the cause of death resulted from complications of hypertension arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (HASCVD).

Individual 1194 (Rett) had a seizure disorder that was noted on the tissue information sheet. For individual 6176 (Rett), the cause of death resulted from a myocardial infarction (MI). For individuals 1420 (Rett) and 1748 (Rett), the cause of death resulted from complications of the disorder, however the specific complication was not provided on the tissue information sheet.

DIOLISTICS OF HUMAN POSTMORTEM HIPPOCAMPAL SLICES

Fixed human postmortem samples (received in 10% formalin) were first extensively washed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS), and then sectioned at 200µm thickness with a vibratome to isolate the hippocampus (Supplemental Figure 1A). Tissue slices were stained with the lipophilic dye, 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI, InVitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) by particle-mediated labeling (“DiOlistics”) (Gan et al., 2000). DiI was diluted in dimethyl chloride (methylene chloride, Sigma; St. Louis, MO). Twenty mg of 1.1µm tungsten particles (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA) were placed on top of a pre-cleaned glass slide and spread out evenly with two pre-cleaned razor blades. The DiI solution was added onto the tungsten particles and allowed to completely evaporate. To prevent clumping of the DiI/tungsten mixture, razor blades were used to break apart and separate the mixture. Additionally, polyvinlypirrollidone (PVP made in fresh in 100% ethanol, Bio-Rad) was added to the DiI/tungsten mixture to further prevent particle clumping and improve their coating to the Tefzel tubing. The DiI-coated tungsten particles were then added to a glass tube with 3mL of water and sonicated for 2hrs. After sonication, the solution was vortexed and then aspirated and coated onto Tefzel tubing for 3hrs. After 3hrs, the solution was removed and the tubing was allowed to dry for 2hrs. DiI-coated tungsten bullets were shot 2–4 times onto individual human hippocampal slices with a custom-modified hand-held gene gun (Helios, Bio-Rad) using 125psi He pressure through a 40µm-pore size filter (Alonso et al., 2004). After labeling with DiI bullets, slices were rinsed and stored in PBS for 24–36hrs at room temperature in the dark to allow diffusion of DiI. Then, slices were post-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C overnight. Slices were finally washed with PBS and mounted on glass slides with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA). Supplemental Figure 1B shows a bright-field example of tungsten bullets within a fixed human hippocampal slice, and the resulting DiI fluorescence.

ORGANOTYPIC SLICE CULTURES

All procedures on experimental animals followed national and international ethical guidelines, and were reviewed and approved by the IACUC at UAB on an annual basis. Hippocampal slice cultures were prepared from postnatal-day 7 to 10 (P7-P10) Sprague-Dawley rats and maintained in vitro as previously described (Stoppini et al., 1991). Briefly, rats were quickly decapitated and their brains aseptically dissected and immersed in ice-cold dissecting solution, consisting of Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), supplemented with glucose (36mM) and antibiotics/antimycotics (1:100; penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin-B). Hippocampi were then dissected and transversely sectioned into ∼500µm slices using a custom-made tissue slicer (Katz, 1987) strung with 20µm-thick tungsten wire (California Fine Wire Company; Grover Beach, CA). Slices were incubated at 4oC for ∼30min, and then plated on tissue culture inserts (0.4µm pore size, Millicell-CM, Millipore Corporation; Billerica, MA). Culture media contained minimum essential media (MEM; 50%), HBSS (25%), heat-inactivated equine serum (20%), L-glutamine (1mM), and D-glucose (36mM). Slice cultures were maintained in incubators at 36oC, 5% CO2, 98% relative humidity (Thermo-Forma, Waltham, MA). All tissue culture reagents were obtained from InVitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), except for glucose, which was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

PARTICLE-MEDIATED GENE TRANSFER

Expression cDNA plasmids encoding small hairpin RNA (shRNA) interfering sequences were obtained from Origene (Rockville, MD). The expression plasmids encoding shRNA sequences are under the control of the human U6 promoter. shRNA interfering sequences consist of a 29-base pair target gene-specific sequence, a 7-base pair loop, followed by a 29-base pair reverse complementary sequence. The MECP2-specific shRNA sequence AATGAGACAGCAGTCTTATGCTTCCAGAA (sequence #2), reduced MeCP2 protein levels by 65%, estimated by quantitative Western blot analyses of PC12 cells co-transfected with human wt MECP2 and shRNA plasmids (Supplemental Figure 2; Larimore et al., 2009). Consistently, MeCP2 expression levels were 55% lower in hippocampal neurons transfected with the same shRNA plasmid (sequence #2) than in untransfected neighboring neurons, as estimated by quantitative MeCP2 immunofluorescence (Supplemental Figure 2; Larimore et al., 2009). Another shRNA sequence, TCAATAACAGCCGCTCCAGAGTCAGTAGT, which did not affect MeCP2 expression, was used as a control for shRNA off-target effects. To overexpress MeCP2, expression cDNA plasmids encoding human WT MECP2 were used as previously described (Kudo, 1998; Kudo et al., 2001; Kudo et al., 2003). Expression plasmids encoding MECP2 mutations commonly identified in RTT individuals were constructed by site directed mutagenesis using PCR, where WT MECP2 was used as a template (Kudo et al., 2001). MeCP2 was tagged with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) that was used to allow identification of transfected cells. The MeCP2-eGFP construct was cloned into a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter expression vector. These expression vectors produced a twofold increase in MeCP2 protein expression compared to untransfected cultured neurons, as measured by quantitative MeCP2 immunofluorescence (Supplemental Figure 2; Larimore et al., 2009).

The above plasmid cDNAs were precipitated onto 50mg of 1.6µm-diameter colloidal Au at a ratio of 62.5µg of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP; Clontech; Mountain View, CA) to 112.5µg of MeCP2-GFP (wildtype or mutant MECP2) and then coated onto Tefzel tubing. A similar protocol was used to coat Au bullets with shRNA interfering sequence plasmids to knockdown the expression of endogenous Mecp2. The pEYFP-C1 plasmid was under control of the human CMV promoter (Clontech). After 6–8 days in vitro (div), slice cultures were bombarded with Au particles accelerated by ∼100psi He from a distance of 2cm using a hand-held gene gun (Helios, Bio-Rad) with a modified nozzle, as previously described (Alonso et al., 2004). The success rate of co-transfection of the same neuron with two cDNA plasmids using the gene-gun has been demonstrated to be >90% (Boda et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2007), reducing the likelihood of analyzing eYFP-positive, MeCP2-negative neurons. After 48hrs or 96hrs post-transfection, hippocampal slice cultures were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in 100mM phosphate buffer (overnight at 4°C), and washed in PBS. Filter membranes around each slice were trimmed, and each slice was individually mounted on glass slides and cover slipped using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA).

LASER-SCANNING CONFOCAL MICROSCOPY

High-resolution images of spiny dendrites in the CA1 region of the human hippocampus showing adequate DiI labeling were acquired with a Fluoview FV-300 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Olympus; Center Valley, PA) using an oil immersion 100X (NA 1.4) objective lens (PlanApo, Olympus), or with a Leica TCS NT SP2 confocal using an oil immersion 100X (NA 1.4) objective lens (Leica; Exton, PA). DiI was excited using a Kr laser (647nm), and detected using standard Texas red filters. Series of optical sections in the z-axis were acquired with 0.1–0.2µm intervals through individual apical dendritic branches.

Pyramidal neurons located in the CA1 and CA3 regions of hippocampal slice cultures displaying eYFP fluorescence throughout the entire dendritic tree and lacking signs of degeneration (e.g. dendritic blebbing) were selected for confocal imaging. High-resolution images of secondary and tertiary branches of apical dendrites were acquired with a Fluoview FV-300 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Olympus) using an oil immersion 100X (NA 1.4) objective lens (PlanApo). eYFP was excited using an Ar laser (488nm), and detected using standard FITC filters. Series of optical sections in the z-axis were acquired at 0.1µm intervals through individual apical dendritic branches.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF DENDRITIC SPINE DENSITY AND MORPHOLOGY

Dendritic spines were identified as small protrusions that extended ≤ 3µm from the parent dendrite, and counted in maximum-intensity projections of the z-stacks using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Care was taken to ensure that each spine was counted only once by following its projection course through the stack of z-sections. Spines were counted only if they appeared continuous with the parent dendrite. Spine density was calculated by quantifying the number of spines per dendritic segment, and normalized to 10µm of dendrite length. In addition, the categorization of different morphological spine types was performed as described (Tyler and Pozzo-Miller, 2003). Spine types were grouped as mature-shaped spines, which included type-I (stubby) and type-II (mushroom) shaped spines, or immature-shaped thin (type-III) spines, following published criteria (Boda et al., 2004). For the purposes of this study, we pooled dendritic spine densities from CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons because the types of spines in secondary and tertiary apical dendrites of CA1 and CA3 neurons (and the excitatory synapses on them) are structurally and functionally comparable: apical secondary and tertiary dendrites in CA3 and CA1 stratum radiatum receive afferent axons from CA3 pyramidal neurons, i.e. they are contacted by the same type of presynaptic neuron (reviewed in Spruston and McBain, 2007). Statistical comparisons supported this approach: spine density was not significantly different between CA1 and CA3 neurons in any of the experimental groups (p>0.05). Detailed information about quantitative analyses is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

TOTAL DENDRITIC LENGTH, PYRAMIDAL NEURONS AND HIPPOCAMPAL SLICES SAMPLED FOR QUANTITATIVE ANALYSES

| Treatment | Treatment Duration | Total length of dendrites (µm) | Number of neurons | Number of slices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eYFP control | 48hrs | 4571.98 | 25 | 15 |

| eYFP control | 96hrs | 4318.46 | 31 | 23 |

| Wildtype MECP2 | 48hrs | 3870.79 | 18 | 16 |

| Wildtype MECP2 | 96hrs | 4454.44 | 23 | 10 |

| R106W MECP2 | 48hrs | 1867.94 | 11 | 10 |

| R106W MECP2 | 96hrs | 4555.15 | 16 | 11 |

| T158M MECP2 | 48hrs | 5042.62 | 25 | 22 |

| T158M MECP2 | 96hrs | 6813.60 | 30 | 14 |

| shRNA Control | 48hrs | 1514.67 | 12 | 10 |

| shRNA Control | 96hrs | 2402.05 | 21 | 11 |

| MECP2 shRNA | 48hrs | 1668.45 | 13 | 10 |

| MECP2 shRNA | 96hrs | 1952.64 | 14 | 12 |

Total number of different CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons and hippocampal slices used for quantitative analyses of dendritic spine density and geometrical morphology. The total length of dendrites measured is presented to provide a sense of the statistical sample analyzed.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF DENDRITIC MORPHOLOGY

Low-resolution images of entire CA3 pyramidal neurons were acquired with a Fluoview FV-300 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Olympus) using an oil immersion 20X (NA 0.5) objective lens (PlanApo). Series of optical sections in the z-axis were acquired at 0.5µm intervals. Dendritic complexity of CA3 pyramidal neurons was measured by a three-dimensional version of the classical Sholl analysis (Sholl, 1953) using the z-stacks of confocal optical sections with Neurolucida software (MicroBrigthField; Colchester, VT). To measure dendritic complexity of traced apical dendrites, series of concentric three-dimensional spheres starting at the soma and spaced at 20µm intervals were used to measure the number of dendritic intersections as a function of the distance away from the soma (20–500µm), as described (Alonso et al., 2004).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

All data were analyzed with two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests, two-way ANOVA (transfection condition x distance from the soma) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test, or unweighted and weighted least square regression analyses using Prism (GraphPad; San Diego, CA); p < 0.05 was considered significant. All data are presented as mean±standard deviation of the mean (SD). Compromise Power Analyses were performed to determine the statistical power given the number of observations, sample means and standard deviations, using G*Power (Erdfelder et al., 1996). These power analyses yielded values of statistical Power (1-β; where β is the Type-II error) larger than 0.90 (i.e. 90% confidence of accepting the null hypothesis when is true).

Results

HIPPOCAMPAL CA1 PYRAMIDAL NEURONS FROM RTT INDIVIDUALS HAVE LOWER DENDRITIC SPINE DENSITY THAN THOSE FROM NON-MR INDIVIDUALS

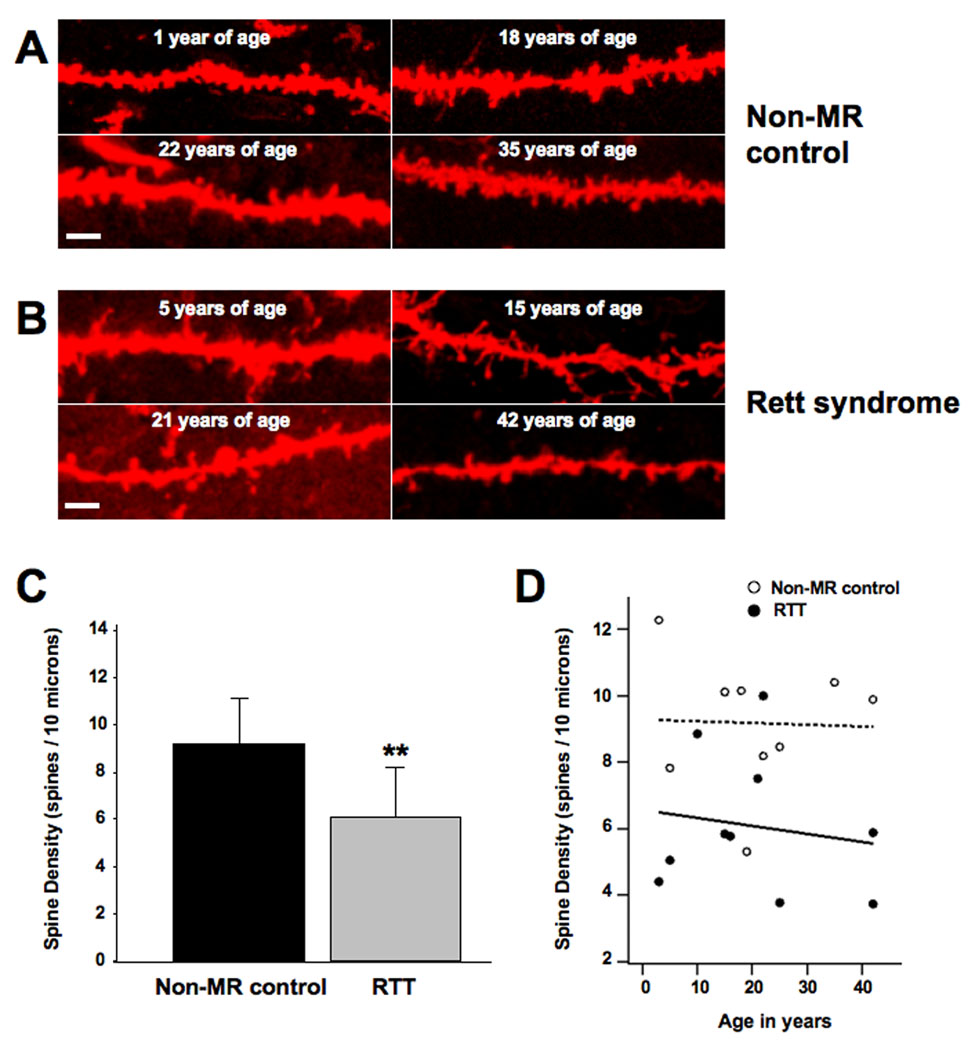

The only prior study on the features of dendritic spines in RTT individuals was performed on cortical samples and lacked quantitative statistical analyses (Belichenko et al., 1994). To perform quantitative analyses of spine density in pyramidal neurons from human hippocampus, postmortem tissue was obtained from female RTT individuals that were 1 to 42 years of age, and compared to age-matched unaffected non-MR female individuals (see Table for all available information from the human brain banks). Unfortunately, information about specific MECP2 mutations in Rett syndrome samples was not available from the brain banks. Individual hippocampal slices (200µm-thick) were stained with the lipophilic fluorescent dye DiI by particle-mediated labeling (“DiOlistics”), and dendritic spines were imaged by laser-scanning confocal microscopy (Supplemental Figure 1, and Fig. 1A, B). Quantitative analyses revealed significantly lower dendritic spine density in secondary and tertiary apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons from RTT individuals compared to unaffected (non-MR) individuals (RTT 6.1±2.1 spines per 10µm of apical dendrite, mean±SD, n=10 individuals, vs. non-MR 9.2±1.9 spines/10µm, n=9 individuals; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0044; Fig. 1C). Both un-weighted and weighted least square regression analyses yielded a lack of significant correlation between age and spine density in controls and RTT neurons (Fig. 1D). These quantitative analyses demonstrate that hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons from RTT individuals have lower spine densities than neurons from non-MR individuals.

FIGURE 1. QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS IN HUMAN POSTMORTEM BRAIN HIPPOCAMPUS REVEALS THAT CA1 PYRAMIDAL NEURONS OF RTT INDIVIDUALS HAVE LOWER DENDRITIC SPINE DENSITY THAN THOSE OF NON-MR INDIVIDUALS.

Formalin-fixed human brain samples were obtained from the Harvard Brain Bank and from the University of Maryland Brain Bank (Table 1 contains all available information on the individuals whose brains were used in this study). A. Representative examples of DiI-stained secondary and tertiary apical dendritic segments of CA1 pyramidal neurons from unaffected (non-MR) female individuals who served as controls. B. Representative examples of DiI-stained secondary and tertiary apical dendritic segments of CA1 pyramidal neurons from female RTT individuals. C. Dendritic spine density expressed per 10µm of dendritic length. D. Least square regression analyses of correlation between age and spine density in controls and RTT neurons. In this and all subsequent figures, data are presented as mean±SD, and * indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p<0.01, and *** indicates p<0.001, after unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (see text for details). In this and all subsequent figures, scale bar represents 2µm.

OVEREXPRESSION OF RTT-ASSOCIATED MECP2 MUTATIONS CAUSED A PERSISTENT REDUCTION IN DENDRITIC SPINE DENSITY IN HIPPOCAMPAL PYRAMIDAL NEURONS

The analysis of dendritic spine densities in human brains representing a static cell population, serves as a direct comparison with that of dendritic spine densities in dynamic slice cultures derived from rat, in each instance involving hippocampal neuron populations. Since RTT results from mutations in MECP2 (Amir et al., 1999; reviewed by Percy, 2001), we investigated the morphological consequences of cell-autonomous expression of missense MECP2 mutations commonly found in RTT individuals. Our cDNA expression plasmids use the CMV promoter, and the resulting protein levels are approximately twofold the endogenous MeCP2 levels, as estimated by quantitative MeCP2 immunocytochemistry (Supplemental Figure 2). We used single amino acid substitutions in the methyl-binding domain of MeCP2 (R106W or T158M), which alter its structure, methylated DNA binding and transcription repressive activity (Ghosh et al., 2008; Ho et al., 2008; Kudo et al., 2001; Kudo et al., 2003). We will first describe the consequences of the overexpression of these RTT-associated MECP2 mutations comparing dendritic spine density and morphology with eYFP-expressing control CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons, and in the following section present the results of the overexpression of wildtype human MECP2. It is important to note that the levels of endogenous Mecp2 gene were not manipulated in these experiments. Since they receive comparable presynaptic input from CA3 pyramidal neurons (reviewed in Spruston and McBain, 2007), the densities of dendritic spines from secondary and tertiary apical dendrites of CA1 and CA3 neurons were pooled in the present studies. Statistical comparisons confirmed that spine densities were not significantly different between the studied CA1 and CA3 dendrites in any of the experimental groups, including after MECP2/Mecp2 manipulations (two-tailed Student’s t-test p>0.05).

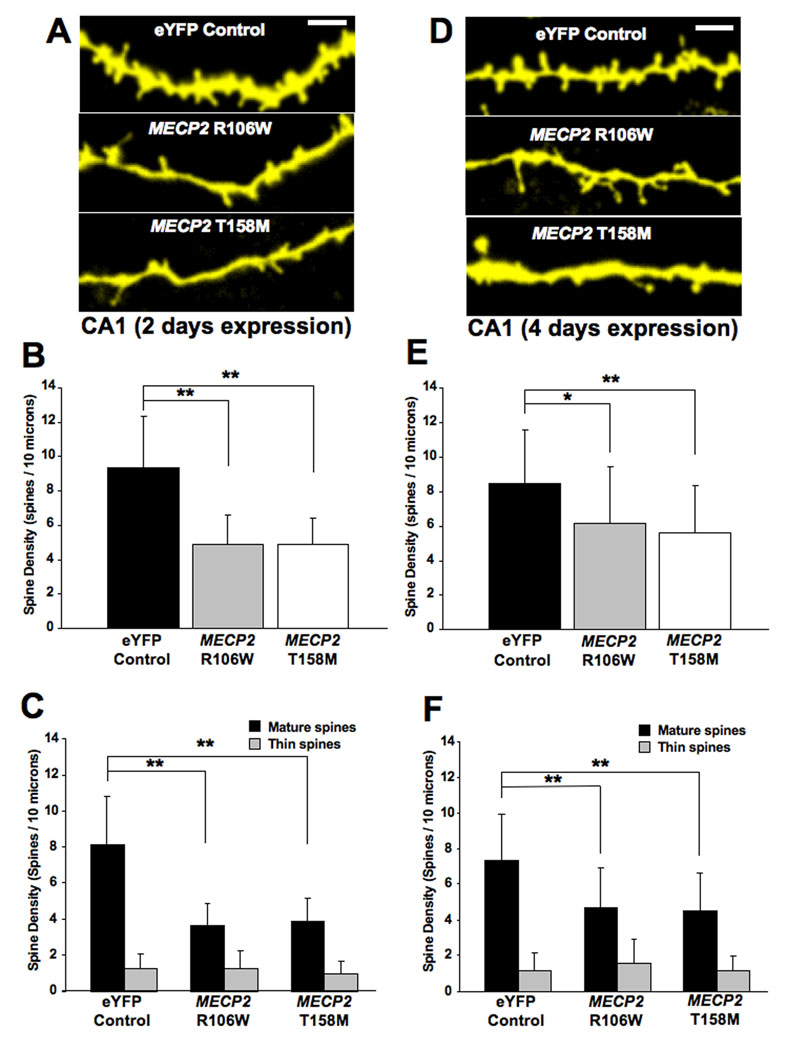

Forty-eight hours after transfection of hippocampal slice cultures, secondary and tertiary apical dendritic branches of pyramidal neurons expressing the R106W mutation showed significantly lower dendritic spine density than eYFP-expressing control neurons (R106W = 4.9±1.7 spines/10µm, mean±SD, 11 cells from 10 slices, vs. eYFP = 9.3±3 spines/10µm, 25 cells from 15 slices; two-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.0001). Expression of the T158M mutation also resulted in lower spine density in pyramidal neurons than in control neurons (4.9±1.5 spines/10µm, 25 cells from 22 slices, vs. eYFP controls; two-tailed Student’s t-test p < 0.0001; Fig. 2A, B).

FIGURE 2. OVEREXPRESSION OF RTT-ASSOCIATED MECP2 MUTATIONS CAUSES A PERSISTENT REDUCTION IN DENDRITIC SPINE DENSITY IN HIPPOCAMPAL PYRAMIDAL NEURONS.

A. Representative examples of apical secondary or tertiary dendritic segments of CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing either an eYFP control plasmid or expression plasmids encoding GFP-tagged mutations in the methyl-binding domain of the MeCP2 (R106W or T158M) after 2 days of expression. B. Dendritic spine density expressed per 10µm of dendritic length. C. Density of each morphological type of dendritic spine (see text for classification criterion). D. Representative examples of apical secondary or tertiary dendritic segments of CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing either the eYFP control plasmid or mutant MECP2 after 4 days of expression). E. Dendritic spine density expressed per 10µm of dendritic length. F. Density of each morphological type of dendritic spine.

Considering the direct relationship between the morphology of dendritic spines and the maturation state and strength of excitatory synapses formed on them (reviewed by Kasai et al., 2003; Nimchinsky et al., 2002; Yuste et al., 2000), we classified dendritic spines into mature (consisting of stubby and mushroom spines) and thin spines, which are considered to represent immature spines (Boda et al., 2004; Tyler and Pozzo-Miller, 2003; reviewed by Harris, 1999). The overexpression of either the R106W mutation or the T158M mutation caused a significant decrease in the density of mature spines in pyramidal neurons [(R106W = 3.6±1.2 mature spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 8.1±2.7 mature spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.001); (T158M = 3.9±1.3 mature spines/10µm, vs. eYFP controls; two-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.001)]. On the other hand, overexpression of either MECP2 mutant did not affect the density of immature thin spines in pyramidal neurons [(R106W = 1.2±0.9 immature spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 1.2±0.8 immature spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.9672); (T158M = 0.98±0.7 immature spines/10µm, vs. eYFP controls; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.1813)]. These results are illustrated in Figure 2C.

When hippocampal pyramidal neurons were allowed to overexpress the mutant forms of MECP2 for an additional 2 days in vitro (div) – for a total of 4 div – their dendritic spine density continued to be lower than eYFP-expressing control neurons. After 4 div, pyramidal neurons expressing the T158M mutation had 5.6±2.7 spines/10µm (30 cells from 14 slices), compared to 8.4±3.1 spines/10µm in eYFP controls (31 cells from 23 slices; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0004). Similar results were observed in pyramidal neurons overexpressing the R106W mutant (R106W = 6.2±3.3 spines/10µm, 16 cells from 11 slices, vs. eYFP controls; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0257; Fig. 2D, E).

Similar to the total spine density, the loss of mature dendritic spines was also a persistent phenotype of mutant MECP2-expressing neurons. After 4 div, pyramidal neurons expressing the T158M mutation still showed a lower density of mature spines than eYFP control cells (T158M = 4.5±2.1 spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 7.3±2.6 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p<0.0001). The overexpression of mutation R106W also reduced mature spines in pyramidal neurons (R106W = 4.7±2.2 spines/10µm, vs. eYFP controls; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0012). On the other hand, expression of mutant MECP2 forms did not change the density of thin spines after 4 div from transfection [(R106W = 1.6±1.3 immature spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 1.1±1 immature spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.2129); (T158M = 1.1±0.8 immature spines/10µm, vs. eYFP controls; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.986; Fig. 2F)].

THE OVEREXPRESSION OF WILDTYPE MECP2 CAUSED A TRANSIENT REDUCTION OF SPINE DENSITY IN HIPPOCAMPAL PYRAMIDAL NEURONS

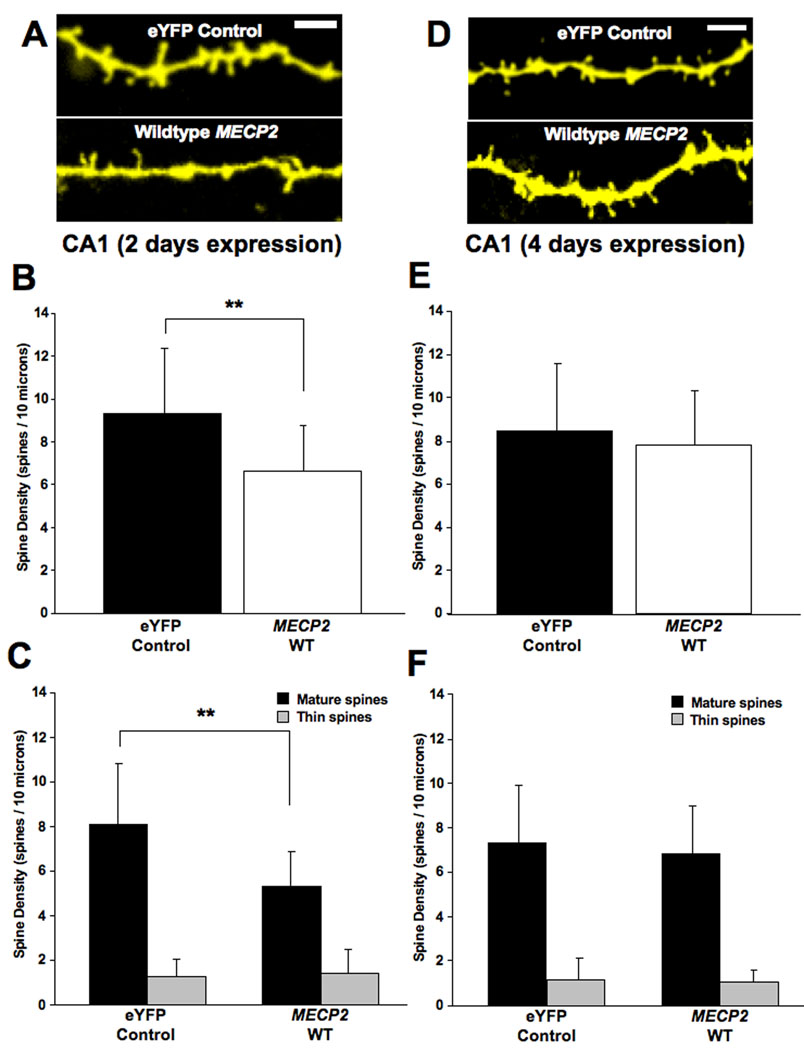

As a control for the overexpression of RTT-associated MECP2 mutant forms, we next analyzed dendritic spine density and morphology in hippocampal pyramidal neurons after transfection of wildtype (WT) human MECP2, which results in a ∼twofold increase in protein level (Supplemental Figure 2). Reminiscent of the effect of mutant MECP2, pyramidal neurons overexpressing WT MECP2 for 2 days in vitro (div) showed lower spine densities than eYFP controls (WT MECP2 = 6.6±2.1 spines/10µm, 18 cells from 16 slices, vs. eYFP = 9.3±3 spines/10µm, 25 cells from 15 slices; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0023; Fig. 3A, B). In addition, the density of mature spines was significantly lower in WT MECP2-expressing pyramidal neurons than in eYFP controls (WT MECP2 = 5.3±1.5 spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 8.1±2.7 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0003). On the other hand, the density of immature thin spines was not affected in pyramidal neurons (WT MECP2 = 1.4±1 spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 1.3±0.8 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.5787; Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3. OVEREXPRESSION OF WILDTYPE MECP2 CAUSES A TRANSIENT REDUCTION IN DENDRITIC SPINE DENSITY IN HIPPOCAMPAL PYRAMIDAL NEURONS.

A. Representative examples of apical secondary or tertiary dendritic segments of pyramidal neurons expressing either the eYFP control plasmid or wildtype MECP2 after 2 days of expression. B. Dendritic spine density expressed per 10µm of dendritic length. C. Density of each morphological type of dendritic spine. D. Representative examples of apical secondary or tertiary dendritic segments of CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing either the eYFP control plasmid or wildtype MECP2 after 4 days of expression. E. Dendritic spine density expressed per 10µm of dendritic length. F. Density of each morphological type of dendritic spine.

In contrast to the persistent spine loss observed in neurons expressing RTT-associated MECP2 mutations (Fig. 2E), the above effects of WT MECP2 on dendritic spine density were transient. Four days after transfection, dendritic spine density in WT MECP2-expressing pyramidal neurons was comparable to that of control neurons expressing eYFP (WT MECP2 = 7.8±2.5 spines/10µm, 23 cells from 10 slices, vs. eYFP = 8.4±3.1 spines/10µm, 31 cells from 23 slices; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.4388; Fig. 3D, E). Furthermore, the density of mature spines was also comparable between controls and WT MECP2-expressing pyramidal neurons (WT MECP2 = 6.8±2.2 spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 7.3±2.6 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.457). As after 2 div, the density of immature thin spines was unaffected after 4 days of expression of WT MECP2 (WT MECP2 = 1.1±0.5 spines/10µm, vs. eYFP = 1.1±1 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.7534; Fig. 3F).

KNOCKDOWN OF ENDOGENOUS MECP2 REDUCED THE DENSITY OF MATURE DENDRITIC SPINES IN HIPPOCAMPAL PYRAMIDAL NEURONS

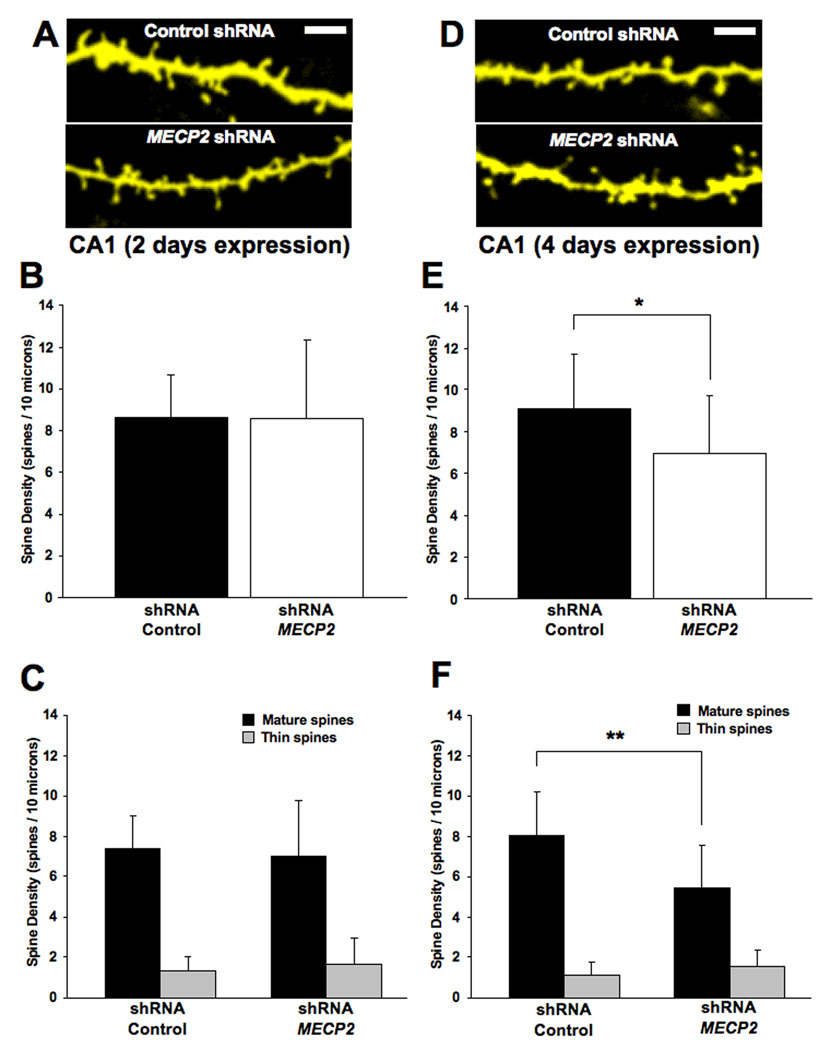

Considering that MECP2 mutations in RTT individuals are thought to be “loss-of-function” mutations (reviewed by Shahbazian et al., 2002a), and the observations that Mecp2 deficient neurons form fewer excitatory synapses in culture, while MECP2 overexpressing neurons form more excitatory synapses in vitro than cultured neurons from wildtype littermates (Chao et al., 2007), we next investigated the consequences of endogenous Mecp2 knockdown. To this aim, pyramidal neurons in hippocampal slice cultures were transfected with plasmids encoding MECP2-specific shRNA interfering sequences. Hippocampal neurons transfected with these shRNA plasmids showed a significant reduction in MeCP2 expression levels compared to untransfected neighboring neurons, as estimated by quantitative MeCP2 immunofluorescence (Supplemental Figure 2). After 48hrs of Mecp2 knockdown, dendritic spine density in pyramidal neurons was comparable to control neurons transfected with an inactive shRNA sequence (MECP2 shRNA = 8.6±3.7 spines/10µm, 13 cells from 10 slices, vs. control shRNA = 9.6±2 spines/10µm, 12 cells from 10 slices; two-tailed Student’s t-test p = 0.9925; Fig. 4A, B). Similarly, Mecp2 shRNA knockdown did not affect the density of mature spines (MECP2 shRNA = 7±2.8 spines/10µm, vs. control shRNA = 7.4±1.6 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.688) or immature thin spines in pyramidal neurons (MECP2 shRNA = 1.6±1.3 spines/10µm, vs. control shRNA = 1.3±0.7 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.4629; Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4. KNOCKDOWN OF ENDOGENOUS MECP2 CAUSES A REDUCTION IN THE DENSITY OF MATURE DENDRITIC SPINES ONLY AFTER 4 DAYS OF TRANSFECTION.

A. Representative examples of apical secondary or tertiary dendritic segments of CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing either the eYFP control plasmid or an shRNA interfering sequence to knockdown endogenous Mecp2 after 2 days of expression. B. Dendritic spine density expressed per 10µm of dendritic length. C. Density of each morphological type of dendritic spine. D. Representative examples of apical secondary or tertiary dendritic segments of CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing either the eYFP control plasmid or an shRNA interfering sequence to knockdown endogenous Mecp2 after 4 days of expression. E. Dendritic spine density expressed per 10µm of dendritic length. F. Density of each morphological type of dendritic spine.

Since the effectiveness of shRNA-mediated knockdown depends on protein turnover, we examined dendritic spine density after 4 days of transfection with shRNA expression plasmids. Indeed, Mecp2 shRNA knockdown significantly reduced dendritic spine density in pyramidal neurons (MECP2 shRNA = 7±2.8 spines/10µm, 14 cells from 12 slices, vs. control shRNA = 9.1±2.7 spines/10µm, 21 cells from 11 slices; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0283; Fig. 4D, E). Similarly, the density of mature spines in MECP2 shRNA-expressing pyramidal neurons was lower than that of control neurons (MECP2 shRNA = 5.5±2.1 spines/10µm, vs. control shRNA = 8±2.2 spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0016). This loss of mature dendritic spines is specific, because the density of immature thin spines was unaffected in pyramidal neurons (Mecp2 shRNA = 1.6±0.8 thin spines/10µm, vs. control shRNA = 1.1±0.6 thin spines/10µm; two-tailed Student’s t-test p=0.0838; Fig. 4F).

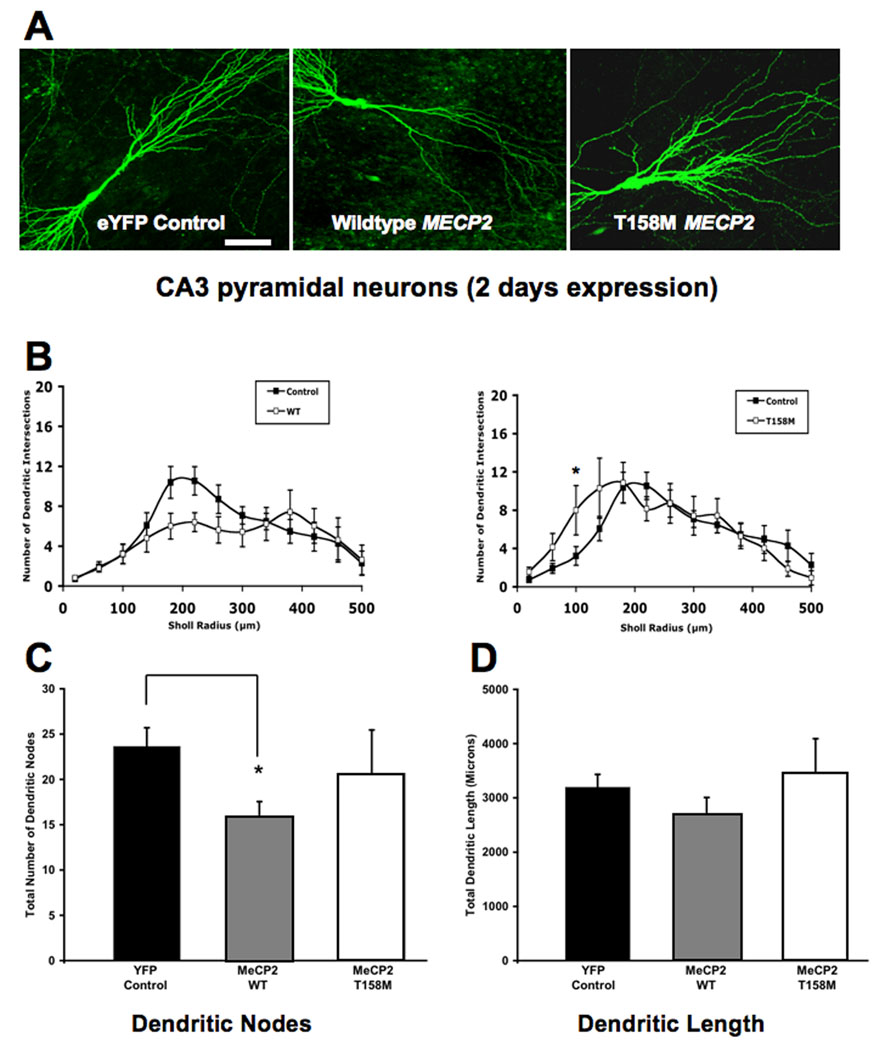

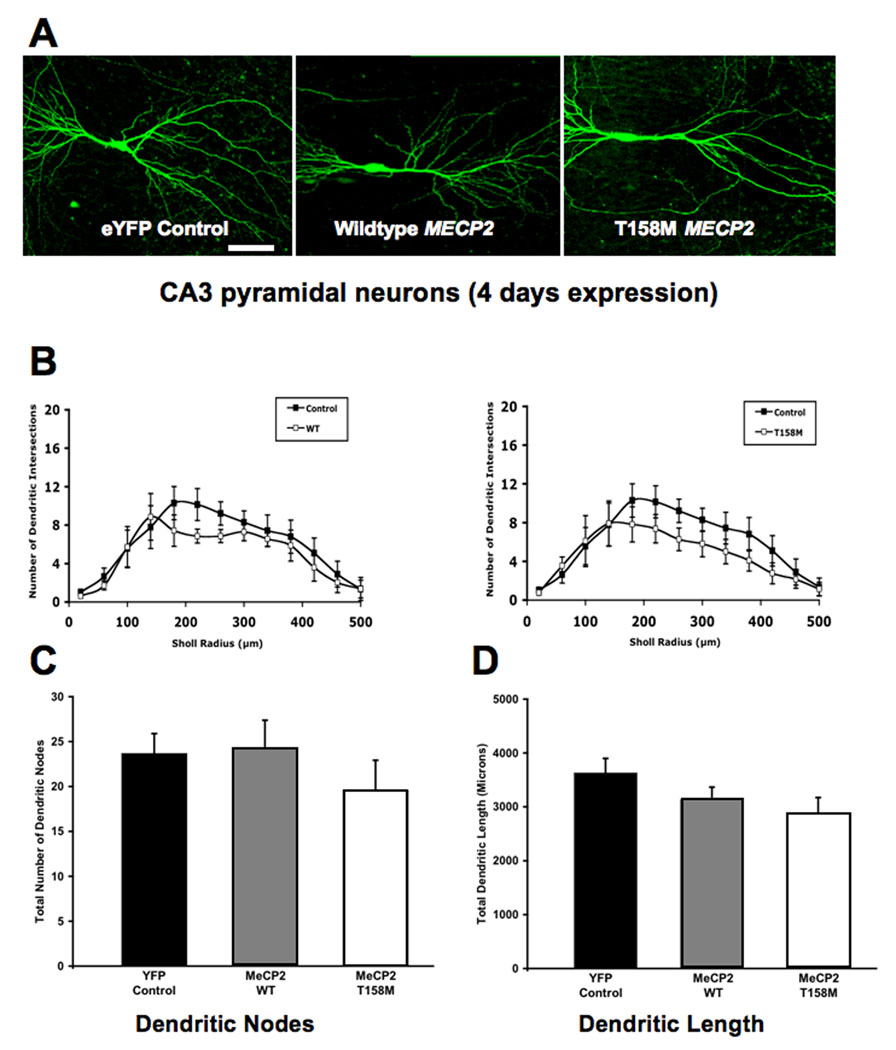

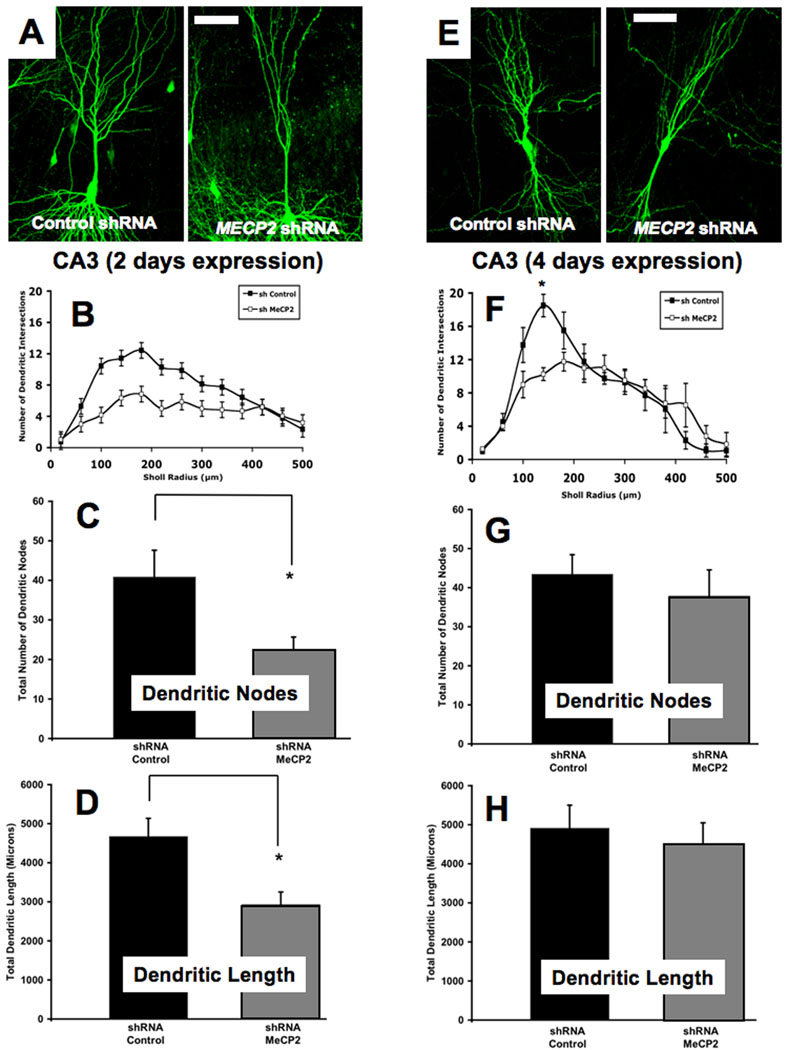

OVEREXPRESSION OF WILDTYPE MECP2 HAD A SMALL EFFECT ON DENDRITIC COMPLEXITY, WHILE KNOCKDOWN OF ENDOGENOUS MECP2 TRANSIENTLY REDUCED DENDRITIC LENGTH AND BRANCHING IN CA3 PYRAMIDAL NEURONS

Another feature of neurodevelopmental disorders associated with mental retardation, such as RTT, is a reduction in the size and complexity of dendritic arbors (reviewed by Kaufmann and Moser, 2000). Pyramidal neurons from the cortex and subiculum of female RTT individuals and from a male individual with a MECP2 deletion displayed reduced dendritic complexity compared to non-MR individuals (Armstrong et al., 1995; Schule et al., 2008). To determine the role of MeCP2 in the growth and branching of hippocampal neurons, we performed a three-dimensional Sholl analysis of dendritic complexity from z-stacks of confocal sections of CA3 pyramidal neurons overexpressing either wildtype or the RTT-associated T158M MECP2 mutation, as well as after endogenous Mecp2 knockdown with a specific shRNA.

After 2 days of transfection, T158M-expressing CA3 pyramidal neurons show a small, but statistically significant higher number of apical dendritic intersections with the Sholl spheres compared to eYFP controls (100µm from the soma: T158M 8±2.6 intersections, 7 cells from 6 slices, vs. eYFP 3.2±0.9, 13 cells from 7 slices; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p<0.05; Fig. 5A, B). This increase is transient, since the number of dendritic intersections in T158M neurons was comparable to control levels after 4 days of expression (11 cells from 8 slices, vs. eYFP, 14 cells from 10 slices; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p>0.05; Fig. 6A, B). The total dendritic length and number of dendritic branch points were not affected after 2 days of expression [(T158M = 3,441±1716µm, vs. eYFP = 3,193±864µm; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.6685) (T158M = 20.7±12.7 branch points, vs. eYFP = 23.6±7.5 branch points; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.5158)]. Similar results were observed after 4 days of transfection [(T158M = 2,870±1053µm, vs. eYFP = 3,627±1048µm; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.0746) (T158M = 19.55±11.7 branch points, vs. eYFP = 23.67±8.6 branch points; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.2995)]. These results are illustrated in Figure 5C, D and Figure 6C, D.

FIGURE 5. OVEREXPRESSION OF WILDTYPE MECP2 TRANSIENTLY REDUCES THE NUMBER OF DENDRITIC NODES AND THE TOTAL DENDRITIC LENGTH, WHILE T158M MECP2 TRANSIENTLY INCREASES DENDRITIC COMPLEXITY (2 DAYS OF EXPRESSION).

A. Representative low magnification views of eYFP-expressing CA3 pyramidal neurons transfected with either wildtype MECP2 or the T158M MECP2 mutant (2 days of expression). B. Three-dimensional Sholl analysis of dendritic complexity. Total number of intersections of CA3 apical dendrites as a function of distance from the soma. C. Total number of apical dendritic nodes. D. Total dendritic length. In this and Figure 6 and Figure 7, the scale bar represents 50µm.

FIGURE 6. OVEREXPRESSION OF WILDTYPE MECP2 TRANSIENTLY REDUCES THE NUMBER OF DENDRITIC NODES AND THE TOTAL DENDRITIC LENGTH, WHILE T158M MECP2 TRANSIENTLY INCREASES DENDRITIC COMPLEXITY (4 DAYS OF EXPRESSION).

A. Representative low magnification views of eYFP-expressing CA3 pyramidal neurons transfected with either wildtype MECP2 or the T158M MECP2 mutant (4 days of expression). B. Three-dimensional Sholl analysis of dendritic complexity. Total number of intersections of CA3 apical dendrites as a function of distance from the soma. C. Total number of apical dendritic nodes. D. Total dendritic length.

In contrast to the small and transient increase in dendritic complexity caused by the T158M mutation, overexpression of wildtype MECP2 did not affect dendritic complexity in CA3 pyramidal neurons after 2 days of transfection (WT MECP2, 5 cells from 4 slices, vs. eYFP, 13 cells from 7 slices; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p>0.05; Fig. 5A, B) or 4 days of transfection (WT MECP2, 7 cells from 7 slices, vs. eYFP, 14 cells from 10 slices; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p>0.05; Fig. 6A, B). Neither WT MECP2 overexpression affected the total dendritic length after 2 days of transfection (WT MECP2= 2,675±742µm, vs. eYFP = 3,193±864µm; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.2559; Fig. 5D) or after 4 days of transfection (WT MECP2 = 3131±665µm, vs. eYFP = 3,627±1048µm; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.2409; Fig. 6D). On the other hand, CA3 pyramidal neurons overexpressing WT MECP2 showed fewer dendritic branch points after 2 days of transfection (WT MECP2 = 15.9±3.7 branch points, vs. eYFP = 23.6±7.5 branch points; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.0454; Fig. 5C). The latter effect was transient, since the total number of dendritic branch points was comparable in both groups after 4 days of expression (WT MECP2 = 24.2±8.9 branch points, vs. eYFP = 23.7±8.6 branch points; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.8833; Fig. 6C).

Lastly, we investigated the consequences of endogenous Mecp2 knockdown for dendritic complexity. After 2 days of expression, CA3 pyramidal neurons transfected with MECP2-specific shRNA showed significantly fewer dendritic branch points and shorter dendrites than control neurons [(MECP2 shRNA = 22.3±8.4, vs. control shRNA = 40.8±17.9; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.0412) (MECP2 shRNA = 2,923±809µm, vs. control shRNA = 4,669±1238µm; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.0133; Fig. 7A–D)]. However, this effect was transient, because the number of dendritic branch points and the total dendritic length after 4 days of Mecp2 knockdown was comparable to those in control neurons [(MECP2 shRNA = 4,506±1084µm, vs. control shRNA = 4,908±1182µm; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.634) (MECP2 shRNA = 37.8±13.5 branch points, vs. control shRNA = 43.4±10 branch points; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p=0.5283; Fig. 7E–H). On the other hand, the effects of Mecp2 knockdown on dendritic complexity became evident only after 4 days of transfection. Dendritic complexity in CA3 pyramidal neurons was comparable in the two groups after 2 days of transfection (MECP2 shRNA, 6 cells from 5 slices, vs. control shRNA, 7 cells from 6 slices; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p>0.05; Fig. 7B), while it was significantly reduced – albeit only within the first 140µm of the apical dendritic tree – after 4 days of Mecp2 knockdown (140µm from soma: MECP2 shRNA 10.3±0.8 intersections, 4 cells from 4 slices, vs. control shRNA 18.5±1.4 intersections, 4 cells from 3 slices; ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test p<0.05; Fig. 7F).

FIGURE 7. KNOCKDOWN OF ENDOGENOUS MECP2 DECREASES THE NUMBER OF DENDRITIC NODES, TOTAL DENDRITIC LENGTH, AND DENDRITIC INTERSECTIONS.

A. Representative low magnification views of eYFP-expressing CA3 pyramidal neurons transfected with an shRNA control plasmid or a specific shRNA interfering sequence designed to knockdown endogenous Mecp2 (2 days of expression). B. Three-dimensional Sholl analysis of dendritic complexity. Total number of intersections of CA3 apical dendrites as a function of distance from the soma. C. Total number of apical dendritic nodes. D. Total dendritic length. E. Representative low magnification views of eYFP-expressing CA3 pyramidal neurons transfected with the shRNA control plasmid or the specific Mecp2 shRNA (4 days of expression). F. Three-dimensional Sholl analysis of dendritic complexity. Total number of intersections of CA3 apical dendrites as a function of distance from the soma. G. Total number of apical dendritic nodes. H. Total dendritic length.

Discussion

Here, we present several novel observations regarding dendritic spine dysgenesis in RTT individuals and the role of the transcriptional regulator MeCP2 on dendritic complexity and dendritic spine density and morphology. First, we show that CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus in female individuals with RTT have lower dendritic spine density than age-matched unaffected (non-MR) female individuals, as observed qualitatively in pyramidal neurons of the motor cortex (Belichenko et al., 1994). Second, overexpression of MECP2 missense mutations common in RTT patients (R106W or T158M) reduced dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, particularly mature dendritic spines (i.e. mushroom and stubby types); on the other hand, overexpression of wildtype MECP2 reduced spine density, but only transiently. It is important to note that the levels of the endogenous Mecp2 gene were not manipulated in these experiments. Third, endogenous Mecp2 knockdown also caused a reduction in dendritic spine density, especially of mature spines. Finally, overexpression of wildtype MECP2 had a small effect on dendritic complexity, while knockdown of endogenous Mecp2 transiently reduced dendritic length and branching in CA3 pyramidal neurons.

The brain pathology of RTT includes decreased neuronal size and increased cell density in numerous brain regions such as the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and the hippocampal formation (Bauman et al., 1995a; Bauman et al., 1995b). A decrease in dendritic branching and in the number of dendritic spines was reported in the cortex of individuals with RTT, or with a deletion of the MECP2 gene (Armstrong et al., 1995; Belichenko et al., 1994; Schule et al., 2008). Furthermore, reduced levels of MAP-2, a dendritic protein involved in microtubule stabilization, were observed throughout the neocortex of RTT patients (Kaufmann et al., 2000; Kaufmann et al., 1995; Kaufmann et al., 1997a). COX-2, a protein enriched in dendritic spines, was also reduced in the cortex of RTT individuals (Kaufmann et al., 1997b). We have extended those studies with quantitative analyses of dendritic spine density in apical secondary and tertiary dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons, which confirmed that RTT individuals have lower spine density than non-MR individuals. Intriguingly, glutamate receptor density has a differential distribution during RTT development, where younger individuals with RTT have a higher density compared to controls, while older individuals have a lower density compared to controls (Blue et al., 1999a; Blue et al., 1999b). The increase in glutamate receptor density may represent a homeostatic compensation for the reduction in dendritic spine density. On the other hand, the elevated glutamate levels measured in forebrain of RTT individuals by high-field strength MRI (Pan et al., 1999) may cause dendritic spine pruning (Segal et al., 2000).

Intriguingly, observations regarding neuronal and synaptic morphology in MeCP2-based models of Rett syndrome have produced varying results, sometimes inconsistent with the available information regarding the cellular neuropathology in RTT patients (Armstrong et al., 1995; Bauman et al., 1995a; Bauman et al., 1995b; Belichenko et al., 1994). However, it is important to note that no other study looked at the consequences of the expression of single-point mutants of MECP2 on dendritic spine density in pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus, as we have done in the present study. Reduced excitatory synaptic transmission and plasticity in Mecp2-deficient mice have been interpreted to reflect a reduced number of excitatory synapses (Asaka et al., 2006; Chao et al., 2007; Dani et al., 2005). Fewer excitatory synapses may reflect delayed neuronal maturation, since newly generated granule cells in the dentate gyrus of Mecp2 null mice have lower dendritic spine density than mature neighboring neurons (Smrt et al., 2007). Consistently, pyramidal neurons in the cortex of Mecp2 null adult mice have reduced dendritic branching and spine density (Fukuda et al., 2005; Kishi and Macklis, 2004). A recent comprehensive study of the two available Mecp2 null mouse models confirmed that granules cells of the dentate gyrus, and pyramidal neurons from hippocampal area CA1 and layers II-III of the motor cortex have lower dendritic spine densities than their control WT littermates (Belichenko et al. 2009a, b). In contrast, hippocampal and cortical neurons of transgenic knockin mice expressing a truncated Mecp2 allele (Mecp2308) – which recapitulate the RTT phenotype (Shahbazian et al., 2002a) – have dendritic, dendritic spine and excitatory synapse morphologies comparable to wildtype mice, despite significant impairments in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory and synaptic plasticity, interpreted as the consequence of the expression of a truncated non-functional MeCP2 protein (Moretti et al., 2006). On the other hand, duplications of the chromosomal region where MECP2 is located in humans have been detected in neurological disorders associated with mental retardation (del Gaudio et al., 2006; Smyk et al., 2008). Intriguingly, transgenic mice that overexpress human MECP2 at approximately twofold the endogenous MeCP2 protein levels have a higher learning rate of hippocampal-dependent tasks and enhanced in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, though they develop seizures after 20 weeks of age, and death occurs shortly thereafter (Collins et al., 2004). The physiological and behavioral phenotypes in MECP2 overexpressing mice may result from a higher density of excitatory synapses compared to wildtype littermates (Chao et al., 2007). Surprisingly, overexpression of wildtype Mecp2 reaching ∼4–5 fold the endogenous levels reduced dendritic branching and increased the length of dendritic spines of hippocampal pyramidal neurons, without affecting spine density (Zhou et al., 2006). It is relevant to note that the latter studies had to overexpress the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-XL to prevent neuronal cell death caused by Mecp2 overexpression at such high levels (Zhou et al., 2006). Incidentally, overexpression of Bcl-XL by itself increased the number of excitatory synapses between cultured hippocampal neurons (Li et al., 2008). The apparent discrepancies with earlier observations made in other experimental systems may originate from different developmental stages (in vivo development vs. 10 days in vitro organotypic slice cultures from P7 hippocampal slices), duration of expression of either a non-functional truncated MeCP2 protein (several weeks expression in vivo) or single-point mutants with reduced activity (4 days expression in vitro), and analyses of Golgi-stained sections by brightfield microscopy vs. individually-labeled neurons by laser-scanning confocal microscopy. It is important to note that, for the purposes of this study, we pooled dendritic spine densities from secondary and tertiary apical dendrites of CA1 and CA3 neurons, which received the same presynaptic input from CA3 neurons (reviewed in Spruston and McBain, 2007). Statistical comparisons confirmed that spine density was not significantly different between the imaged CA1 and CA3 dendrites in none of the experimental groups, including after MECP2/Mecp2 manipulations. Of relevance to RTT, where mutant forms of MeCP2 are expressed in a mosaic fashion due to X chromosome inactivation, the “spotted” transfection of RTT-associated MECP2 mutations yielded by particle-mediated gene transfer in hippocampal slice cultures resulted in a more dramatic dendritic spine loss than the shRNA-mediated knockdown of the endogenous MeCP2 protein expression.

Considering the direct relationship between the morphology of dendritic spines and the maturation state and strength of excitatory synapses on them (reviewed by Kasai et al., 2003; Nimchinsky et al., 2002; Yuste et al., 2000), it is consistent that overexpression of RTT-associated MECP2 mutations cause a selective loss of mature dendritic spines, i.e. stubby and mushroom types (Boda et al., 2004; Tyler and Pozzo-Miller, 2003; reviewed by Chapleau and Pozzo-Miller, 2007; Harris, 1999). Since larger spines (including stubby and mushroom spines) are the postsynaptic compartment of excitatory synapses that are stronger than those formed onto thin spines, as estimated by the amplitude of AMPAR-mediated postsynaptic currents (Matsuzaki et al., 2001; Matsuzaki et al., 2004), a lower density of morphologically mature spines suggests that overexpression of RTT-associated MECP2 mutations or endogenous Mecp2 knockdown reduce the strength of excitatory synapses. Such weakening of excitatory synaptic strength may precede spine and synapse shrinkage and pruning (Bastrikova et al., 2008; Becker et al., 2008; Segal et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2004).

Lastly, our observations indicate the importance of MeCP2 expression levels for the maintenance of dendritic tree structure. Indeed, wildtype MECP2 overexpression or endogenous Mecp2 knockdown reduced the branching of apical dendrites, as previously shown (Zhou et al., 2006). However, the overexpression of mutant MECP2 caused the opposite effect, increasing dendritic complexity. Since the overexpression of mutant MECP2 causes a significant loss in the total number of spines, especially of mature spines, the enhancement in dendritic complexity might reflect a compensatory homeostatic mechanism in the face of significant loss of mature excitatory synapses.

In summary, we have presented evidence in support of a cell-autonomous role of MeCP2 levels in the maintenance of mature dendritic spines and the complexity of the dendritic tree of postnatal pyramidal neurons within an established neuronal network. The mutations in the methyl-binding domain of MeCP2 used in our studies (R106W and T158M) were shown to reduce its binding to methyl-CpG-dinucleotides, impairing its transcriptional repression of a reporter gene (Ballestar et al., 2000; Ghosh et al., 2008; Kudo et al., 2001; Kudo et al., 2003; Yusufzai and Wolffe, 2000). Recently, a gene profiling study identified 2,582 genes symmetrically misregulated in the hypothalamus of Mecp2 null and MECP2 overexpressing mice, suggesting that they represent primary targets (Chahrour et al., 2008). Unexpectedly, 85% of them seem to be activated by MeCP2 based on the fact that they were up-regulated in MECP2 overexpressing mice and down-regulated in Mecp2 null mice. It remains unknown whether RTT-causing mutations affect MeCP2’s role in transcriptional activation, repression or both. Taken together, our results demonstrate reduced density of dendritic spines – the postsynaptic element of excitatory synapses – in CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus of individuals with RTT, a distinct dendritic phenotype that is recapitulated in post-mitotic neurons expressing RTT-associated MECP2 mutations or after shRNA-mediated endogenous Mecp2 knockdown, suggesting that this phenotype represents a cell-autonomous consequence of MeCP2 dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

A. Cresyl violet staining of a representative human brain section revealing the characteristic cytoarchitecture of the hippocampus and subregions (dentate gyrus, subiculum, CA3 and CA1). B. Representative formalin-fixed hippocampal slice (200µm thickness) stained with DiI by particle-mediated labeling (“DiOlistics”). top, Brightfield image of the CA1 region of the hippocampus. bottom, DiI fluorescence image from the same field of view. Note the tungsten bullets used to deliver DiI (arrows).

A. Western immunoblots of PC-12 cells transfected with human wt MECP2-expressing plasmids, or different shRNA interfering sequence plasmids to knockdown endogenous Mecp2. Sequence #2 produced a ∼65% reduction in MeCP2 protein levels. B. Primary hippocampal neurons were co-transfected with shRNA sequence #2 and eGFP, and immunostained with anti-MeCP2 antibodies (red) to determine MeCP2 protein levels by quantitative immunofluorescence. Inset shows the same field of view in the green fluorescence channel to identify the GFP transfected neuron. Note that the MeCP2 positive (red) neuron on the right, which can be identified as GFP positive (green) in the inset, is dimmer than the one on the left due to the expression of the MeCP2 shRNA plasmid #2. C. Primary hippocampal neurons were transfected with expression plasmids to overexpress wildtype MECP2 or the T158M mutation and immunostained with anti-MeCP2 antibodies (red) to determine MeCP2 protein levels by quantitative immunofluorescence. Green fluorescence represent neurons transfected with eGFP-tagged MeCP2, and red immunofluorescence shows MeCP2 positive neurons. As in B., the inset shows the green channel. D. Population data from the quantitative fluorescence estimation of MeCP2 levels in hippocampal neurons. Mecp2 knockdown caused a ∼55% reduction in MeCP2 immunofluorescence, while transfection with expression plasmids resulted in a twofold increase in MeCP2 immunofluorescence, all compared to untransfected neurons within the same fields of view.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH grants NS40593 and NS057780, IRSF and the Civitan International Foundation (LP-M). We also thank the assistance of the UAB Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC; P30-HD38985) and the UAB Neuroscience Cores (P30-NS47466, P30-NS57098). Human tissue was obtained from the NICHD Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD. We thank Dr. Carolyn Schanen (Nemours Biomedical Research, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE, USA), and Mr. J. Matthew Rutherford for discussions and comments on the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Mark Beasley for statistical analyses (IDDRC Biometry Core A; UAB School of Public Health, Biostatistics).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Akbarian S, Chen RZ, Gribnau J, Rasmussen TP, Fong H, Jaenisch R, Jones EG. Expression pattern of the Rett syndrome gene MeCP2 in primate prefrontal cortex. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:784–791. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso M, Medina JH, Pozzo-Miller L. ERK1/2 activation is necessary for BDNF to increase dendritic spine density in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Learn Mem. 2004;11:172–178. doi: 10.1101/lm.67804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D, Dunn JK, Antalffy B, Trivedi R. Selective dendritic alterations in the cortex of Rett syndrome. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaka Y, Jugloff DG, Zhang L, Eubanks JH, Fitzsimonds RM. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity is impaired in the Mecp2-null mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestar E, Yusufzai TM, Wolffe AP. Effects of Rett syndrome mutations of the methyl-CpG binding domain of the transcriptional repressor MeCP2 on selectivity for association with methylated DNA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7100–7106. doi: 10.1021/bi0001271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastrikova N, Gardner GA, Reece JM, Jeromin A, Dudek SM. Synapse elimination accompanies functional plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3123–3127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman ML, Kemper TL, Arin DM. Microscopic observations of the brain in Rett syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 1995a;26:105–108. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman ML, Kemper TL, Arin DM. Pervasive neuroanatomic abnormalities of the brain in three cases of Rett's syndrome. Neurology. 1995b;45:1581–1586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker N, Wierenga CJ, Fonseca R, Bonhoeffer T, Nagerl UV. LTD induction causes morphological changes of presynaptic boutons and reduces their contacts with spines. Neuron. 2008;60:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko NP, Belichenko PV, Mobley WC. Evidence for both neuronal cell autonomous and nonautonomous effects of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 in the cerebral cortex of female mice with Mecp2 mutation. Neurobiol Dis. 2009a;34:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko PV, Oldfors A, Hagberg B, Dahlstrom A. Rett syndrome: 3-D confocal microscopy of cortical pyramidal dendrites and afferents. Neuroreport. 1994;5:1509–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko PV, Wright EE, Belichenko NP, Masliah E, Li HH, Mobley WC, Francke U. Widespread changes in dendritic and axonal morphology in Mecp2-mutant mouse models of Rett syndrome: evidence for disruption of neuronal networks. J Comp Neurol. 2009b;514:240–258. doi: 10.1002/cne.22009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue ME, Naidu S, Johnston MV. Altered development of glutamate and GABA receptors in the basal ganglia of girls with Rett syndrome. Exp Neurol. 1999a;156:345–352. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue ME, Naidu S, Johnston MV. Development of amino acid receptors in frontal cortex from girls with Rett syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999b;45:541–545. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199904)45:4<541::aid-ana21>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boda B, Alberi S, Nikonenko I, Node-Langlois R, Jourdain P, Moosmayer M, Parisi-Jourdain L, Muller D. The mental retardation protein PAK3 contributes to synapse formation and plasticity in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10816–10825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2931-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel S, Revel MO, Kelche C, Zwiller J. Expression of the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 in rat brain. An ontogenetic study. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong ST, Qin J, Zoghbi HY. MeCP2, a Key Contributor to Neurological Disease, Activates and Represses Transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HT, Zoghbi HY, Rosenmund C. MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron. 2007;56:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapleau CA, Pozzo-Miller L. Activity-dependent structural plasticity of dendritic spines. In: Byrne J, editor. Learning and Memory: a Comprehensive Reference. Volume 4. Oxford: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 695–719. [Google Scholar]

- Collins AL, Levenson JM, Vilaythong AP, Richman R, Armstrong DL, Noebels JL, David Sweatt J, Zoghbi HY. Mild overexpression of MeCP2 causes a progressive neurological disorder in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2679–2689. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couvert P, Bienvenu T, Aquaviva C, Poirier K, Moraine C, Gendrot C, Verloes A, Andres C, Le Fevre AC, Souville I, Steffann J, des Portes V, Ropers HH, Yntema HG, Fryns JP, Briault S, Chelly J, Cherif B. MECP2 is highly mutated in X-linked mental retardation. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:941–946. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.9.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani VS, Chang Q, Maffei A, Turrigiano GG, Jaenisch R, Nelson SB. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12560–12565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Gaudio D, Fang P, Scaglia F, Ward PA, Craigen WJ, Glaze DG, Neul JL, Patel A, Lee JA, Irons M, Berry SA, Pursley AA, Grebe TA, Freedenberg D, Martin RA, Hsich GE, Khera JR, Friedman NR, Zoghbi HY, Eng CM, Lupski JR, Beaudet AL, Cheung SW, Roa BB. Increased MECP2 gene copy number as the result of genomic duplication in neurodevelopmentally delayed males. Genet Med. 2006;8:784–792. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000250502.28516.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdfelder E, Faul F, Buchner A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods. 1996;28:1–11. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala JC, Spacek J, Harris KM. Dendritic spine pathology: cause or consequence of neurological disorders? Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:29–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Itoh M, Ichikawa T, Washiyama K, Goto Y. Delayed maturation of neuronal architecture and synaptogenesis in cerebral cortex of Mecp2-deficient mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:537–544. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan WB, Grutzendler J, Wong WT, Wong RO, Lichtman JW. Multicolor "DiOlistic" labeling of the nervous system using lipophilic dye combinations. Neuron. 2000;27:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemelli T, Berton O, Nelson ED, Perrotti LI, Jaenisch R, Monteggia LM. Postnatal loss of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 in the forebrain is sufficient to mediate behavioral aspects of Rett syndrome in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh RP, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Nikitina T, Gierasch LM, Woodcock CL. Rett syndrome-causing mutations in human MeCP2 result in diverse structural changes that impact folding and DNA interactions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20523–20534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803021200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM. Structure, development, and plasticity of dendritic spines. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho KL, McNae IW, Schmiedeberg L, Klose RJ, Bird AP, Walkinshaw MD. MeCP2 binding to DNA depends upon hydration at methyl-CpG. Mol Cell. 2008;29:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR. Dendritic development and mental defect. Neurology. 1970;20:381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR. Dendritic development in neocortex of children with mental defect and infantile spasms. Neurology. 1974;24:203–210. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jugloff DG, Jung BP, Purushotham D, Logan R, Eubanks JH. Increased dendritic complexity and axonal length in cultured mouse cortical neurons overexpressing methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung BP, Jugloff DG, Zhang G, Logan R, Brown S, Eubanks JH. The expression of methyl CpG binding factor MeCP2 correlates with cellular differentiation in the developing rat brain and in cultured cells. J Neurobiol. 2003;55:86–96. doi: 10.1002/neu.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kankirawatana P, Leonard H, Ellaway C, Scurlock J, Mansour A, Makris CM, Dure LSt, Friez M, Lane J, Kiraly-Borri C, Fabian V, Davis M, Jackson J, Christodoulou J, Kaufmann WE, Ravine D, Percy AK. Early progressive encephalopathy in boys and MECP2 mutations. Neurology. 2006;67:164–166. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223318.28938.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai H, Matsuzaki M, Noguchi J, Yasumatsu N, Nakahara H. Structure-stability-function relationships of dendritic spines. Trends Neurosci. 1987;26:360–368. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC. Local circuitry of identified projection neurons in cat visual cortex brain slices. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1223–1249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-04-01223.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Johnston MV, Blue ME. MeCP2 expression and function during brain development: implications for Rett syndrome's pathogenesis and clinical evolution. Brain Dev. 2005;27 Suppl 1:S77–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, MacDonald SM, Altamura CR. Dendritic cytoskeletal protein expression in mental retardation: an immunohistochemical study of the neocortex in Rett syndrome. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:992–1004. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Moser HW. Dendritic anomalies in disorders associated with mental retardation. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:981–991. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Naidu S, Budden S. Abnormal expression of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) in neocortex in Rett syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26:109–113. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Taylor CV, Hohmann CF, Sanwal IB, Naidu S. Abnormalities in neuronal maturation in Rett syndrome neocortex: preliminary molecular correlates. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997a;6 Suppl 1:75–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Worley PF, Taylor CV, Bremer M, Isakson PC. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression during rat neocortical development and in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 1997b;19:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(96)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N, Macklis JD. MECP2 is progressively expressed in post-migratory neurons and is involved in neuronal maturation rather than cell fate decisions. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo S. Methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 represses Sp1-activated transcription of the human leukosialin gene when the promoter is methylated. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5492–5499. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo S, Nomura Y, Segawa M, Fujita N, Nakao M, Dragich J, Schanen C, Tamura M. Functional analyses of MeCP2 mutations associated with Rett syndrome using transient expression systems. Brain Dev. 2001;23 Suppl 1:S165–S173. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(01)00345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo S, Nomura Y, Segawa M, Fujita N, Nakao M, Schanen C, Tamura M. Heterogeneity in residual function of MeCP2 carrying missense mutations in the methyl CpG binding domain. J Med Genet. 2003;40:487–493. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.7.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimore J, Chapleau CA, Kudo S, Theibert A, Percy AK, Pozzo-Miller L. Bdnf overexpression in hippocampal neurons prevents dendritic atrophy caused by Rett-associated MECP2 mutations. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Chen Y, Jones AF, Sanger RH, Collis LP, Flannery R, McNay EC, Yu T, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy B, Bossy-Wetzel E, Bennett MV, Pypaert M, Hickman JA, Smith PJ, Hardwick JM, Jonas EA. Bcl-xL induces Drp1-dependent synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2169–2174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711647105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Structural abnormalities of the cerebral cortex in human chromosomal aberrations: a Golgi study. Brain Res. 1972;44:625–629. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Pyramidal cell abnormalities in the motor cortex of a child with Down's syndrome. A Golgi study. J Comp Neurol. 1976;167:63–81. doi: 10.1002/cne.901670105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuyama T, Matsuo M, Jing JJ, Tabara Y, Kitsuki K, Yamagata H, Kan Y, Miki T, Ishii K, Kondo I. Classic Rett syndrome in a boy with R133C mutation of MECP2. Brain Dev. 2005;27:439–442. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GC, Nemoto T, Miyashita Y, Iino M, Kasai H. Dendritic spine geometry is critical for AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moog U, Smeets EE, van Roozendaal KE, Schoenmakers S, Herbergs J, Schoonbrood-Lenssen AM, Schrander-Stumpel CT. Neurodevelopmental disorders in males related to the gene causing Rett syndrome in females (MECP2) Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2003;7:5–12. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3798(02)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CD, Thacker EE, Larimore J, Gaston D, Underwood A, Kearns B, Patterson SI, Jackson T, Chapleau C, Pozzo-Miller L, Theibert A. The neuronal Arf GAP centaurin alpha1 modulates dendritic differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2683–2693. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti P, Levenson JM, Battaglia F, Atkinson R, Teague R, Antalffy B, Armstrong D, Arancio O, Sweatt JD, Zoghbi HY. Learning and memory and synaptic plasticity are impaired in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J Neurosci. 2006;26:319–327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2623-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullaney BC, Johnston MV, Blue ME. Developmental expression of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 is dynamically regulated in the rodent brain. Neuroscience. 2004;123:939–949. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ED, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. MeCP2-dependent transcriptional repression regulates excitatory neurotransmission. Curr Biol. 2006;16:710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimchinsky EA, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Structure and function of dendritic spines. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:313–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.160008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan JW, Lane JB, Hetherington H, Percy AK. Rett syndrome: 1H spectroscopic imaging at 4.1 Tesla. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:524–528. doi: 10.1177/088307389901400808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy AK. Rett syndrome: clinical correlates of the newly discovered gene. Brain Dev. 2001;23 Suppl 1:S202–S205. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(01)00350-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy AK, Lane JB. Rett syndrome: model of neurodevelopmental disorders. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:718–721. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster H. Neurons and Their Supporting Cells. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System. [Google Scholar]

- Purpura DP. Dendritic spine "dysgenesis" and mental retardation. Science. 1974;186:1126–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4169.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schule B, Armstrong D, Vogel H, Oviedo A, Francke U. Severe congenital encephalopathy caused by MECP2 null mutations in males: central hypoxia and reduced neuronal dendritic structure. Clin Genet. 2008;74:116–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal I, Korkotian I, Murphy DD. Dendritic spine formation and pruning: common cellular mechanisms? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01499-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazian M, Young J, Yuva-Paylor L, Spencer C, Antalffy B, Noebels J, Armstrong D, Paylor R, Zoghbi H. Mice with truncated MeCP2 recapitulate many Rett syndrome features and display hyperacetylation of histone H3. Neuron. 2002a;35:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazian MD, Antalffy B, Armstrong DL, Zoghbi HY. Insight into Rett syndrome: MeCP2 levels display tissue- and cell-specific differences and correlate with neuronal maturation. Hum Mol Genet. 2002b;11:115–124. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholl DA. Dendritic organization in the neurons of the visual and motor cortices of the cat. J Anat. 1953;87:387–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smrt RD, Eaves-Egenes J, Barkho BZ, Santistevan NJ, Zhao C, Aimone JB, Gage FH, Zhao X. Mecp2 deficiency leads to delayed maturation and altered gene expression in hippocampal neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]