Abstract

Objective This study tested whether violent victimization by peers was associated with alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents, and whether adaptive coping styles moderated associations. Methods A total of 247 urban Mexican-American and European-American adolescents aged 16–20 years were interviewed. Results Independent of demographics and violent perpetration, adolescents victimized by violence reported greater alcohol and tobacco use. Adolescents who engaged in higher levels of behavioral coping (e.g., problem solving) reported less substance use, independent of violence variables. Interaction effects showed that violent victimization was associated with greater substance use only among adolescents who engaged in lower levels of cognitive coping (e.g., focusing on positive aspects of life). Substance use was relatively low among adolescents who engaged in higher levels of cognitive coping, regardless of whether they had been victimized. Conclusions Enhancement of cognitive coping skills may prevent engagement in substance use as a stress response to violent victimization.

Keywords: adolescence, coping, substance use, stress, violence

National estimates suggest that 20–30% of youth experience violent victimization by peers, such as physical assault or attack with a weapon (Slovak & Singer, 2002; Stein, Jaycox, Kataoka, Rhodes, & Vestal, 2003). Although much of the literature has focused on peer violence within impoverished, inner-city communities, these rates are typical of urban, suburban, and rural communities (Slovak & Singer, 2002; Stein et al., 2003). Violent victimization may have consequences other than physical injury among youth, including posttraumatic stress and depression (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Ozer & Weinstein, 2004). Adolescents who have been victimized by violence are also more likely to engage in alcohol and tobacco use, initiate substance use early, engage in more frequent use, and become substance use dependent (Ellickson, Saner, & McGuigan, 1997; Schwab-Stone et al., 1995). Studies on peer violence and substance use have included nationally representative (Kilpatrick et al., 2000) and predominantly African-American urban samples of youth (Albus, Weist, & Perez-Smith, 2004; Sullivan, Farrell, & Kliewer, 2006), as well as relatively understudied ethnic minority subgroups such as Central-American (Kliewer et al., 2006) and Mexican-American youth (Ramos-Lira, Gonzalez-Forteza, & Wagner, 2006). Associations between substance use and both violent victimization (Brady, Tschann, Pasch, Flores, & Ozer, in press) and violent perpetration (Brady et al., in press; White, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Farrington, 1999) are bidirectional, suggesting that substance use may both be a response to violence involvement and place adolescents at risk for further violence involvement.

According to stress-coping theory, a stressor will not negatively impact individuals who possess resources to adequately cope (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). To our knowledge, no studies have examined coping as a moderator of the association between violent victimization and substance use among adolescents. Some studies suggest that adaptive coping may protect youth from broadly defined behavioral problems in response to violence exposure. In one prospective study of urban African American and Latino male adolescents, community violence exposure was associated with increases in violent behavior only among adolescents who did not engage in adaptive coping (e.g., focusing on positive aspects of life) during the time of violence exposure (Brady, Gorman-Smith, Henry, & Tolan, 2008). Cross-sectional studies of adolescents and young adults show that coping similarly moderates associations between community violence exposure and delinquency (Rosario, Salzinger, Feldman, & Ng-Mak, 2003), externalizing behavior (McGee, 2003), and aggressive behavior (Scarpa & Haden, 2006). Cross-sectional (Wills, 1986) and prospective (Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, Cleary, & Shinar, 2001) studies among ethnically diverse adolescents show that associations between general stressors and substance use are not as strong among adolescents who engage in high levels of behavioral coping (e.g., problem solving) or cognitive coping (e.g., positive reappraisal of stress).

The present cross-sectional study tests whether coping moderates the association between violent victimization by peers and substance use among urban Mexican-American and European-American adolescents. We address two issues of conceptual significance. First, we examine whether engagement in cognitive and behavioral coping both moderate associations between violent victimization and substance use, or whether only cognitive coping acts as a moderator. When stressors are relatively uncontrollable, attempting to change negative thoughts and feelings (i.e., cognitive coping) may be more effective in reducing distress than attempting to change one's situation (i.e., behavioral coping; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Zeidner, 2005). Second, we adjust for violent perpetration in analyses to conduct a more direct test of stress-coping theory. The cooccurrence of different health risk behaviors among youth has been described as a problem behavior syndrome (Jessor, Donovan, & Costa, 1996). Although a problem behavior syndrome may explain the clustering of violent perpetration with other forms of health risk behavior, it may not provide the best explanation of why violent victimization is associated with substance use, particularly after adjustment for perpetration.

We hypothesize that violent victimization will be associated with greater levels of alcohol and tobacco use, independent of age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and violent perpetration. We further hypothesize that the association between violent victimization and substance use will be stronger in magnitude among adolescents who engage in low rather than high levels of cognitive coping. We do not expect behavioral coping to act as a moderator. Our sample composition allows us to test for potential interactions involving ethnicity and gender.

Methods

Procedure

Participants were part of a larger study examining parental conflict and adolescent functioning (Tschann, Flores, Pasch, & Marin, 1999; Tschann et al., 2002). The present study's data were obtained 4 years after initial recruitment. At initial recruitment, families were randomly selected from membership lists of a large health maintenance organization (HMO) serving an urban, Northern California community. One adolescent from each family and parents were eligible if the adolescent was aged 12–15, biological parents were residing together, all three family members were either Mexican American or US born European American, and the adolescent had no severe learning disability. Seventy-three percent of eligible families participated (N = 302). Four years after initial recruitment, families were contacted and asked to participate in an additional interview that included all of the present study's constructs (N = 247; retention rate = 82%; interviews completed in October, 1999). The Institutional Review Board and HMO approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from parents and adolescents aged 18 years and older; informed assent was obtained from younger adolescents.

Participants

One hundred and twenty-six Mexican-American and 121 European-American adolescents completed interviews for the present study (total N = 247; 54% male; aged 16–20). Mexican-American parents reported an average 8 years of education (SD = 4), while European-American parents reported 16 years (SD = 2). The average Hollingshead (1975) occupational score was 6.7 (SD = 1.5) for European-American parents, corresponding to small business owners and managers, while the average score was 3.3 (SD = 1.8) for Mexican-American parents, corresponding to semiskilled workers. Family socioeconomic status was calculated by averaging across four standardized variables: years of education and occupation score for each parent.

Measures

Violence Exposure

Participants reported their victimization by and perpetration of 10 peer-based violent acts during the previous 12 months. Items were developed based on focus groups and existing measures of violence exposure (CDC, 1992). The percentages of adolescents reporting victimization by and perpetration of the following acts, respectively, were as follows: starting a fight (18%, 19%), getting hurt in a fight (14%, 5%), attacking (17%, 23%), beating up (10%, 18%), pulling a knife (10%, 4%), pulling a gun (6%, 2%), threatening with a club/bottle/screwdriver (13%, 7%), hurting with a club/bottle/screwdriver (6%, 4%), stabbing with a knife (1%, 0.5%), and firing a gun (3%, 1%). Dichotomous victimization and perpetration groups were created for analyses; 29 and 28% of participants reported any violent victimization and perpetration, respectively, while 23% reported both types of violence.

Substance use

Alcohol and tobacco use during the previous 6 months was assessed. Participants completed five items from the Drinking Styles Questionnaire (Christensen, Smith, Roehling, & Goldman, 1989), including ever using alcohol, drinking frequency, quantity typically consumed, drunkenness frequency, and maximum amount consumed in one drinking episode. A quarter of adolescents reported not drinking during the past 6 months. Among adolescents who reported drinking, median responses indicated that half of adolescents drank at least once per month, usually consumed at least two drinks per occasion, became drunk at least twice during the previous 6 months, and consumed a maximum of six or more drinks in one drinking episode. We standardized and averaged across items within all adolescents to create a composite score [M (SD) = 0.08 (0.82); range, −1.39 to 1.45; α =.91]; higher scores indicate higher levels of alcohol use. Frequency of tobacco use was assessed by a single item [M (SD) = 2.32 (2.61); 0—have never smoked, 1—have smoked, but not during the past 6 months, through 8-A pack a day or more]. Thirty-five percent of adolescents reported never smoking and 23% reported smoking, but not during the past 6 months. Among adolescents who smoked during the past 6 months, two modal responses emerged: 3—once in a while, and 6—one to five cigarettes a day.

Coping

Cognitive and behavioral coping were assessed using Wills’ Coping Inventory (Wills, 1986), which does not restrict responses to a specific time frame. Six cognitive coping items measured the extent to which adolescents selectively focused on positive aspects of their situation and made positive comparisons between their situation and that of others (e.g., “I try to notice only the good things in life;” M (SD) = 2.45 (0.48); range, 1.33–4.00; α =.58). Seven behavioral coping items measured the extent to which adolescents adopted an active approach to information gathering, decision making, and problem solving (e.g., “I think about the choices that exist before I take action;” M (SD) = 2.63 (0.58); range, 1.14–3.86; α =.80). Question stems were modified to begin, “When I am having a problem at home ….” By assessing how adolescents coped with family problems rather than violent victimization by peers, we ensured that we would have data on coping styles in response to conflict.

Results

Bivariate Associations

Several correlations involved demographic variables (Pearson r's =.14–.29 in magnitude, p's <.05). Age was associated with greater alcohol use and behavioral coping, male gender was associated with violence involvement, and Mexican-American ethnicity was associated with perpetration and lower levels of substance use and cognitive coping. Low socioeconomic status was associated with violence involvement, lower levels of alcohol use and behavioral coping, and greater levels of cognitive coping. Violent victimization and perpetration (r =.70), alcohol and tobacco use (r =.51), and cognitive and behavioral coping (r =.22) were correlated at p <.01. All violence involvement and substance use variables were correlated with one another (r's =.17–.28; p's <.01). Low levels of behavioral coping were associated with violence involvement and greater substance use (r's =.16–.24; p's <.05), while cognitive coping was not associated with violence involvement or substance use.

Linear Regression of Substance use on Violent Victimization

Table 1 (see Base Model) shows results from regression analyses of individual substance use variables on violent victimization, adjusting for demographic variables and violent perpetration. Violent victimization was associated with greater levels of alcohol and tobacco use.

Table 1.

Linear Regressions of Substance Use Variables on Violent Victimization and Copinga

| Alcohol use (N = 247) |

Tobacco use (N = 247) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Adj. R2 | β | Adj. R2 | |||

| Base Model | Age | .22*** | .04 | |||

| Female gender | .01 | .12 | ||||

| Mexican American ethnicity | −.12 | −.18 | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | .10 | .03 | ||||

| Violent perpetration | .11 | .22* | ||||

| Violent victimization | .19* | .13 | .19* | .13 | ||

| Model 1 | Step 1 | Behavioral coping | −.18** | .16 | −.19** | .16 |

| Step 2 | Victimization × behavioral coping | −.10 | .17 | .00 | .15 | |

| Model 2 | Step 1 | Cognitive coping | −.08 | .14 | −.11 | .14 |

| Step 2 | Victimization × cognitive coping | −.14* | .15 | −.12* | .15 | |

aModels 1 and 2 include Base Model variables as covariates. Adjusted (Adj.) R2 estimates the proportion of variation in the dependent variable that is collectively explained by independent variables in the model, while adjusting for the tendency for R2 to inflate as the number of independent variables in a model increases.

*p <.05; **p <.01; ***p <.001.

Main Effects and Interaction Effects Involving Coping

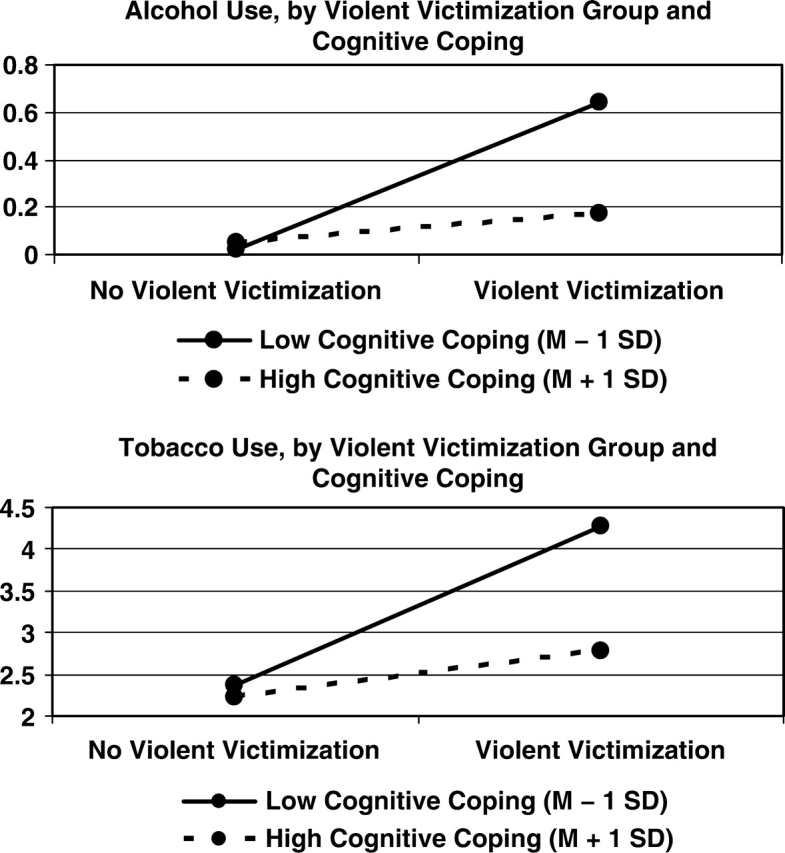

Behavioral coping was associated with lower alcohol and tobacco use, while cognitive coping had no main effects (see Table I, Step 1 of Models 1 and 2). Cognitive, but not behavioral coping, modified associations between violent victimization and substance use (see Step 2 of Models 1 and 2). Violent victimization was not associated with substance use among adolescents who engaged in high levels of cognitive coping, but was associated with greater alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents who engaged in low levels of cognitive coping (Fig. 1). Interaction tests between violent victimization, coping, and ethnicity or gender were not significant (data not shown in table).

Figure 1.

Interaction effects between violent victimization and cognitive coping.

Discussion

As hypothesized, violent victimization was associated with greater alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents, and cognitive coping moderated these associations. Results are consistent with the idea that cognitive coping may protect adolescents from engaging in substance use as a stress response to violent victimization. Cognitive coping is focused on changing negative thoughts and feelings rather than changing the situation (Wills, 1986). In some situations, behavioral coping might decrease the likelihood of violent victimization. However, cognitive coping may still be necessary to reduce distress and the likelihood that adolescents choose potentially harmful activities as a means of escaping from distress.

Although behavioral coping did not moderate associations between violent victimization and substance use in the present study, other research suggests that behavioral coping protects adolescents from engaging in substance use as a response to general stressors (Wills, 1986; Wills et al., 2001). In the present study, adolescents who engaged in higher levels of behavioral coping engaged in less substance use, independent of victimization history. Results suggest that both cognitive and behavioral coping strategies may contribute to long-term positive outcomes among adolescents. Interestingly, lower levels of behavioral coping were reported by adolescents who had been involved with violence and by adolescents of lower socioeconomic status. It may be that environments characterized by less control provide fewer opportunities to learn behavioral coping strategies. Behavioral coping strategies may also be less effective in environments that are disempowering. Because behavioral coping may result in more positive outcomes than engagement in cognitive coping alone when stressors are controllable (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), disadvantaged adolescents may benefit from targeted interventions to strengthen both cognitive and behavioral coping skills.

Limitations of the present study include its cross-sectional design. Coping was not assessed at each time point of the larger study from which present data were drawn. Although adolescents’ self-report of sensitive behaviors approximates actual behavior (Harrison, 1995), our reliance on self-report introduces the possibility of method and informant bias. Relatedly, bivariate analysis indicated that half of the variance in violent victimization could be explained by perpetration. However, examination of tolerance values suggested that potential multicollinearity was not a problem in statistical models. Additional limitations are that coping was assessed in relation to family conflict and the internal consistency for cognitive coping was somewhat low. However, hypothesized interactions involving cognitive coping were found, and research suggests that adolescents’ coping strategies are moderately stable across family and peer-based stressors (Griffith, Dubow, & Ippolito, 2000; Jaser et al., 2007). Although our data were collected in 1999, results are consistent with related studies conducted at different time periods (Wills, 1986; Zeidner, 2005). Thus, we have no reason to expect that findings would not generalize to the present day. Results may not generalize to families in which biological parents are not residing together or to families that cannot obtain health insurance.

Our sample of European-American and Mexican-American adolescents with health insurance extends existing literature. Observed lower levels of substance use and higher levels of violence involvement among Mexican-American adolescents are consistent with national data (CDC, 2006). Lack of significant interactions involving ethnicity may reflect adjustment for socioeconomic status or inadequate power to detect ethnic differences in the strength of associations. Further studies examining potential ethnic differences should be conducted.

A stress-coping framework has implications for the manner in which clinical and health professionals, parents, and other key adults address youth violence and substance use. Substance use may appear to be an attractive means of coping with distress among youth who have been victimized. Our findings highlight the importance of existing prevention and intervention programs that identify substance use as a maladaptive method of coping with stress and attempt to build adolescents’ coping skills (Botvin & Griffin, 2004; Sussman, Dent, & Stacy, 2002). Enhancement of adolescents’ cognitive coping skills may reduce the likelihood that they cope with violent victimization and other stressors through substance use. Enhancement of behavioral coping skills may also reduce substance use among adolescents, although this process may occur independently from the experience of violent victimization. Health promotion programs should help adolescents to build a broad repertoire of coping skills and to select the most adaptive strategies for specific situations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UCSF Health Psychology Postdoctoral Fellows Research Group for feedback on an early version of this article. We are also grateful to Lilia Cardenas, Martha Castrillo, Jorge Palacios, Philip Pantoja, and Stephanie Whitzell for assistance with data collection, and to Seth Duncan and Philip Pantoja for data management. This research was supported by grants MNCJ-060623 and R40MC00118 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, awarded to Dr Tschann. Part of Dr Brady's work was funded by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32 MH019391) while she was a postdoctoral fellow at UCSF. We would like to thank the families who participated in the Adolescent Health Research Project. We also thank the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute, E. Marco Baisch, and Charles J. Wibbelsman for providing access to members of Kaiser Permanente.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Albus KE, Weist MD, Perez-Smith AM. Associations between youth risk behavior and exposure to violence: Implications for the provision of mental health services in urban schools. Behavior Modification. 2004;28:548–564. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW. Life skills training: Empirical findings and future directions. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2004;25:211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, & Tolan PH. Proactive coping reduces the impact of community violence exposure on violent behavior among African American and Latino male adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 36. 2008:105–115. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Tschann JM, Pasch LA, Flores E, Ozer EJ. Violence involvement, substance use, and sexual activity among Mexican American and European American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behaviors related to unintentional and intentional injuries among high school students—United States, 1991. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1992;41:760–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55:1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen BA, Smith GT, Roehling PV, Goldman MS. Using alcohol expectancies to predict adolescent drinking behavior after one year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:93–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson P, Saner H, McGuigan KA. Profiles of violent youth: Substance use and other concurrent problems. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:985–991. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Developmental Psychopathology. 1998;10:101–116. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith MA, Dubow EF, Ippolito MF. Developmental and cross-situational differences in adolescents’ coping strategies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LD. The validity of self-reported data on drug use. Journal of Drug Issues. 1995;25:91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Department of Sociology: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Champion JE, Reeslund KL, Keller G, Merchant MJ, Benson M, et al. Cross-situational coping with peer and family stressors in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:917–932. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa F. Personality, perceived life chances, and adolescent behavior. In: Hurrelmann K, Hamilton SF, editors. Social problems and social contexts in adolescence: Perspectives across boundaries. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Murrelle L, Prom E, Ramirez M, Obando P, Sandi L, et al. Violence exposure and drug use in Central America youth: Family cohesion and parental monitoring as protective factors. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:455–478. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McGee Z. Community violence and adolescent development: An examination of risk and protective factors among African American youth. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2003;19:293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Weinstein RS. Urban adolescents’ exposure to community violence: The role of support, school safety, and social constraints in a school-based sample of boys and girls. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:463–476. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Lira L, Gonzalez-Forteza C, Wagner FA. Violent victimization and drug involvement among Mexican middle school students. Addiction. 2006;101:850–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Ng-Mak DS. Community violence exposure and delinquent behaviors among youth: The moderating role of coping. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Haden SC. Community violence victimization and aggressive behavior: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:502–515. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Stone ME, Ayers TS, Kasprow W, Voyce C, Barone C, Shriver T, et al. No safe haven: A study of violence exposure in an urban community. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1343–1352. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovak K, Singer MI. Children and violence: Findings and implications from a rural community. Children and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2002;19:35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka S, Rhodes HJ, Vestal KD. Prevalence of child and adolescent exposure to community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:247–264. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000006292.61072.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:119–137. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Stacy AW. Project towards no drug abuse: A review of findings and future directions. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26:354–365. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.5.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Flores E, Marin BV, Pasch LA, Baisch EM, Wibbelsman CJ. Interparental conflict and risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents: A cognitive-emotional model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:373–385. doi: 10.1023/a:1015718008205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Flores E, Pasch LA, Marin BV. Assessing interparental conflict: Reports of parents and adolescents in European American and Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:269–283. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Developmental associations between substance use and violence. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:785–803. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Stress and coping in early adolescence: Relationships to substance use in urban school samples. Health Psychology. 1986;5:503–529. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.5.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, Shinar O. Coping dimensions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:309–323. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner M. Contextual and personal predictors of adaptive outcomes under terror attack: The case of Israeli adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:459–470. [Google Scholar]